Abstract

There are a plethora of approaches to construct microtissues as building blocks for the repair and regeneration of larger and complex tissues. Here we focus on various physical and chemical trapping methods for engineering three-dimensional microtissue constructs in microfluidic systems that recapitulate the in vivo tissue microstructures and functions. Advances in these in vitro tissue models have enabled various applications, including drug screening, disease or injury models, and cell-based biosensors. The future would see strides toward the mesoscale control of even finer tissue microstructures and the scaling of various designs for high throughput applications. These tools and knowledge will establish the foundation for precision engineering of complex tissues of the internal organs for biomedical applications.

INTRODUCTION

Tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary field in which cells and materials are engineered to construct bioartificial structures that can improve, mimic, repair, or even replace some biological functions in vivo.1, 2 Engineered tissues could also function as in vitro models of living tissues for drug screening and for fundamental biological understanding of structure-function relations in three-dimensional (3D) microenvironments.3, 4 Major challenges were defined in tissue engineering two decades ago;5 significant progress has since been made with ∼50 000 000 people in the United States alone benefiting from various forms of artificial organ therapy.6 The field has experienced ups and downs due to some failed product launches or clinical trials.7 The industry is emerging with tissue-engineered products with a revenue of USD$1.5 billion by 2008.6

The cells inside the living tissues in vivo are subjected to various extracellular cues such as cell-cell, cell-matrix interactions, mass transfer of oxygen and nutrients from blood, soluble factor availability, rigidity control, and mechanosensing [Fig. 1a]. Current tissue engineering research adopts either the top-down or bottom-up approach. The top-down approach involves defining the entire large tissue features by the biomaterials scaffolds and seeding cells into these scaffolds. The bottom-up approach involves engineering microtissue constructs and then multiplying them into large tissues.8, 9 The top-down approach develops relatively large polymeric scaffolds with a feature size of millimeters–centimeters.10 This classical approach has been successful for tissues whose functions are relatively independent from the fine structural details.11 For in vivo implantation, uncontrolled remodeling of tissue constructs would yield reasonably functional tissue reconstruction (e.g., skin or bone∕cartilage).12 The major challenge of this approach is how to better control the local extracellular microenvironments such as vascularization, matrix,13, 14 and cell distributions15 for engineering complex internal tissues such as the gut, lung, liver, kidney, etc., whose functions are greatly affected by the fine structural features.

Figure 1.

Schematic of 3D microtissue: in vivo and in vitro scenarios.

The bottom-up strategy takes advantage of the repeating structural and functional units like nephrons, liver lobules, or ganglions.16, 17 This approach aims to craft small tissue building blocks with precision-engineered structural and functional microscale features. There is a spectrum of methods for creating these tissue building blocks; e.g., cell aggregation by self-assembly,17, 18 hybridization of complementary nucleotides on the functionalized cells,19 cell-encapsulating hydrogels or peptide microgels beads,20 cell sheet engineering,21, 22 and organ printing.13, 23 The tissue constructs created from these methods could be connected to form larger tissue constructs by packing randomly,17 programmed assembly,19 stacking layer-by-layer,14 or directed assembly using the hydrophobic effect in the water∕oil interface.16

One recent method for bottom-up tissue engineering is with microfluidic systems that have become important tools in biotechnology, chemical synthesis, and analytical chemistry.24, 25 Microfluidic systems are being explored for controlling the cellular microenvironment to study complex and fundamental biological processes and to build cell-based assays.26 The extracellular microenvironments (0.1–10 μm), tissue microstructures formed by a group of cells (10−∼400 μm), and intercellular structures (>400 μm) to control the cell-cluster cross-talks are all amenable to manipulation in microfluidic systems.8 The fluid flow in a microfluidic system is laminar and it efficiently regulates media and temperature changes.27 Growth of complex tissue constructs is possible in microfluidics, as they provide a constant media (mimic the blood) supply of oxygen, nutrients, growth factors, and other soluble signaling molecules,28 as well as efficient removal of metabolic wastes [Fig. 1b]. Most systems culturing cells on surfaces as 2D monolayers impose stringent requirements to intrachannel surface chemistry and often stretch the cells artificially as the cells adhere strongly to surfaces. The 2D cultured cells either do not adhere properly to the surfaces or absorb excessive soluble wastes fouling the local extracellular microenvironments. The stretched cells often lose their differentiated phenotypes.29, 30 More recently, microfluidic systems with certain chemical or physical trapping features can enable 3D packing of cells with enhanced cell-cell interactions within the diffusion-limited scale (typically <250 μm). These 3D culture systems are relatively insensitive to the intrachannel surface chemistry and can better mimic the in vivo environment. Cells are typically trapped together as cell clusters to maintain 3D cell morphology and enhanced cellular and tissue functions.31 Here we will review various cell trapping methods in microfluidic systems and analyze their strength and limitations.

CELL TRAPPING TECHNIQUES

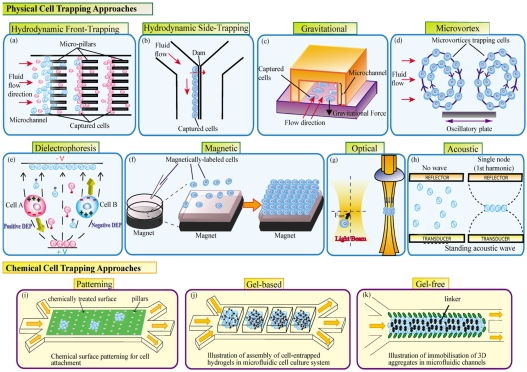

The construction of microtissues in a microfluidic system starts with the basic step of trapping cells into cell clusters to facilitate cell-cell interaction and culture multiple cells together as a colony or functional tissue niche. Such 3D culture greatly improves the restoration of cellular and tissue functions. The cell entrapment can be executed via physical or chemical trapping methods.

Physical trapping

There are a number of physical trapping methods that separate cells from each other as well as from environmental factors such as excessive fluidic shear stress. Such separation methods also allow small clusters of cells to be grouped together to facilitate cell-cell interactions and to ensure that small cell clusters remain separated from the other clusters to maintain optimal mass transfer with the environments for effective oxygen and nutrient delivery as well as metabolic waste removal. Therefore, the physical trapping methods developed for cell separation form the basis for more sophisticated microtissue engineering to be discussed below.

Hydrodynamic trapping

Hydrodynamic trapping is the most common method for cell trapping. Cells are immobilized in certain regions of the chip after being separated from the flow by different mechanical barriers or obstacles.32, 33 The obstacle or barrier dimensions are similar to the sizes of the cells to be captured. There have been a few ways to trap cells by hydrodynamic trapping: (i) front-trapping, (ii) side-trapping, (iii) gravity trapping, and (iv) microvortex trapping.

Front-trapping enables the cells to be trapped by obstacles placed on the flow path [Fig. 2a]. Carlson et al.34 had initially utilized hydrodynamic flow to force the freshly isolated blood through a lattice of 5 μm wide channels of varying lengths. The small red blood cells easily penetrate through the channels while the larger white blood cells are slowed by the channels yielding different fractions of granulocytes, monocytes, and T-lymphocytes at different distances from the channel entry. Zheng et al.35 used a parylene membrane filter with arrays of circular holes of 10-μm diameter to trap the circulating tumor cells and hence separate them from other blood cells. The circulating tumor cells could be recovered with 90% efficiency in 10 min. A single cell can also be trapped or paired in arrays of U-shaped microstructures or Pachinko-style traps along the flow path.36, 37 These arrays can be redesigned to trap a group of cells into small cell clusters. Jin et al.38 also developed a two-layered PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane) device in which the cell trapping barriers are inflated to form wells for trapping cells and then later deflated to retrieve the spheroids formed from the trapped cells.

Figure 2.

Cell trapping techniques.

Side-trapping traps cells by placing obstacles parallel to the flow path [Fig. 2b]. Yang et al.39 docked and aligned a single line of HL-60 cells along a dam structure lying between two parallel channels. The hydrodynamic pressure difference between the parallel channels enables the docking of cells along the channel of higher flow rate. This side-trapping of cells along the dam potentially ensures less shear stress on the cells compared to front-trapping of cells. Takeuchi’s group pioneered a trap-and-release mechanism for holding beads and cells along a straight channel.40, 41 Fluidic resistance during the hydrodynamic flow is the principle behind the trapping while the release is executed by laser-induced microbubble formation. We have combined the front- and side-trapping mechanisms into a microfluidic channel with dimensions of 104 μm (length)×600 μm (width)×100 μm (height), in arrays of micropillars (dimensions 30×50 μm and a 20 μm gap size) located in the center of the microfluidic channel to filter and trap the cells using a withdrawal flow.31, 42, 43, 44, 45 These trapped cells maintain good viability, 3D morphology, sufficient cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, as well as high levels of albumin secretion and UDP-glucuronyltransferase (UGT) activity for in vitro toxicology applications.

Gravitational force in conjunction with flow can trap cells in a chip. The cells move along the flow and sediment into the microwells. Khademhosseini et al.46 developed polyethylene glycol (PEG) microstructures inside the microfluidic channels to trap both adherent and nonadherent cell types. NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and mouse embryonic stem cells (ES cells) were introduced into the channels and the flow is intermittently stopped, allowing the cells to settle in wells [Fig. 2c]. The authors have also developed another array of channels to trap different cell types inside the microwells on substrates.47 They used a secondary array of channels, orthogonally aligned and attached to already patterned substrates, for delivering various fluid regents to the trapped cells. The precise positioning of cells inside the microwells allows reduced shear stress on the cells inside the wells.

A contactless way of hydrodynamic trapping is with recirculating flows through microvortices.48 When cells flow along a microvortex, they are trapped in the flow path and concentrated over time. Lin et al.49 used microvortices developed on an oscillating microplate through Lorentz force to trap two clusters of cells in a microdevice [Fig. 2d]. Lutz et al.50 generated steady streams to trap cells by allowing oscillations (produced by an audible frequency of ∼1000 Hz) inside a microchannel to interact with a fixed cylinder. In the microvortices, cells experience very low-shear stress (∼10−2 N∕m2); the trapping efficiency is high; the trapping forces are adjustable; and the method is insensitive to the cell type or media properties.

Hydrodynamic trapping chips do not require a sophisticated experimental infrastructure, are simple to manufacture, and are relatively easy to operate. The hydrodynamic approach can apply to almost all cell types over extended culture periods, and the trapping density could be very high. Since hydrodynamic approaches have mostly been contact based, there could be irreversible attachment of the trapped cells with the intrachannel surfaces or trapping at the unintended locations. Microvortex trapping and other contactless trapping techniques described below can potentially address this problem.

Dielectrophoretic (DEP) trapping

Cells can be manipulated using gradients of an electric field, a phenomenon known as dielectrophoresis. A DEP force controls the movement of the cell to the desired location. The DEP force F acting on a cell with radius r is given by51

| (1) |

where εm is the absolute permittivity of the suspending medium and ∇E is the local electric field (rms) intensity. Re[k] is the real part of the polarization factor, defined as follows:

| (2) |

where and are the complex permittivity of the particle and medium, respectively. The complex permittivity for a dielectric material can be described by its permittivity ε and conductivity σ, where ω is the angle frequency of the applied electrical field E [Eq. 2]. Depending on the electrical properties of the cells, media, and the frequency of the electric field, the dielectrophoretic force that acts on the cell can be positive (pDEP) or negative (nDEP). For pDEP, the displacement of the cell will be through the regions with high electric field strength while for nDEP to regions with low electric field strength, respectively [Fig. 2e]. An example of the pDEP and nDEP phenomenon is presented in Fig. 3 (enhanced online). In a microfluidic channel defined by electrodes,52 a yeast cell population is suspended in a buffer. First, the cells are trapped between the tips of the electrode’s structure (pDEP). Once the frequency is changed, the cells move to the wells (nDEP). Finally, a bubble is generated in the microfluidic channel, as the voltage is further increased (undesired Joule effect). Various dielectrophoretic methods for cell trapping∕manipulation can be classified according to the various approaches for generating gradients of an electric field: (i) traveling wave DEP, (ii) insulating iDEP, (iii) optical DEP, and (iv) conventional DEP.

Figure 3.

Movie showing yeast cell trapping on a DEP chip (enhanced online).

Traveling wave DEP is the method of changing the phase of the applied electric field53, 54 in order to achieve the gradient of the electric field between parallel electrodes. Insulating DEP (iDEP) consists of generating a gradient of an electric field in a capacitor-like structure using a nonhomogenous dielectric medium.55, 56 Lewpiriyawong et al.57 proposed a microfluidic H filter fabricated in PDMS that induced a nonuniform electric field, generating a nDEP force on the particles. The iDEP method has been used for separating two different cell populations like viable and dead cells using HeLa cells58 or yeast cells59 as models. This method can potentially be applied to sort out two live cell populations and trap and concentrate them for microtissues construction on a chip. Chiou et al.60 proposed an optically induced DEP method where the gradient of the electric field is generated using an optical image on a photodiode surface. An optoelectrofluidic platform for differentiation of normal oocytes using a pDEP force that is induced by a dynamic image projected from a liquid crystal display was proposed by Hwang et al.61 Another method used the spatial or temporal conductivity gradient for generating gradients of an electric field and hence dielectrophoretic force.62, 63 A classical or conventional method to generate gradients of the electric field is using a nonuniform shape of the electrodes. These electrodes can be 2D,63 3D,64, 65, 66, 67 a combination between a thin electrode and an extruded electrode,68 or 3D DEP gates generated by placing the electrodes on top and at the bottom of the microfluidic channel.69 Chang’s group modulated the dielectrophoretic force that acts on different cells in a microfluidic device by buffer selection and cross-linking.70, 71 Lately, interdigitated comb electrodes have been used to generate gradients of an electrical field in a vertical direction; as a result, the cells can be trapped on the bottom of the microfluidic channel.72

There are two main problems associated with manipulating cells using an electric field: (i) the Joule heating effect and (ii) the influence of the electric field on the cell (especially on cell membrane). The applied voltage generates a large power density in the fluid surrounding the electrode, especially in the area near to the edge of the electrode. Due to the small volume, this could give rise to a large temperature increase; and the large temperature gradients in the medium would affect the viability of the cells. Anticipating this problem, there are a few studies about temperature consideration in microfluidic DEP devices.73, 74, 75 For thermal consideration, a low conductivity buffer is recommended where most of the cell population experience pDEP. If for a special cell type there are restrictions regarding the buffer and only suspending media (in most of the cases saline solutions) must be used, the cells will experience mainly nDEP. Flanagan et al. proposed a low conductivity buffer used for pDEP trapping for sorting a population of stem cells with different dielectric properties.76 The buffer used (8.5% sucrose [wt∕vol], 0.3% glucose [wt∕vol], and 0.725% [vol∕vol] RPMI) has a conductivity of 150 μS∕cm. Mouse neural stem∕precursor cells, differentiated neurons, and differentiated astrocytes were incubated in this buffer up to 6 h at room temperature, and no deteriorating cell viability was observed.

A second problem is the influence of the electric field on cells that remain a potential showstopper for some cell types and applications. Strong electric fields as well as strong gradients of electric fields needed for cell manipulation might affect the cell physiology.77 The range of frequency used in dielectrophoresis—up to megahertz, allows the interaction between the electric field and cell at the membrane level;78 the electric field may end up affecting voltage-sensitive proteins.79

Magnetophoretic trapping

Another method for cell trapping is with a magnetic field.80, 81 The manipulation of the cell is performed using a magnetic force F that can be expressed as82, 83

where V is the volume of the particle, Δλ is the difference between the magnetic susceptibilities of the particle and media, B is the applied magnetic field, and μ0 is the magnetic permeability in a vacuum. As a result, if ∇B=0, there is no force acting on the particle; a condition for a stronger force being an increased gradient of the magnetic field. The resultant magnetic force used in microfluidic devices is in the range of 2–1000 pN.33 Depending on the properties of the cell, there are three main types of magnetic trapping: (i) using the diamagnetic properties of cells,84 (ii) using paramagnetic properties of cells,85 and (iii) using surface chemistry to attach the cell to magnetic particles.86

The main advantage of the first method is that it is applicable to any diamagnetic particle as long as its magnetic susceptibility is different from that of the medium and no chemical or physical modification of the surface is required. The disadvantage of a diamagnetic method is the requirement of a field modulator and the relatively small distance from this field modulator to the trapping surface (in microfluidic channel).81, 84 The paramagnetic properties of the cell have been exploited for separation of red blood cells (RBCs) from blood by trapping the RBCs.87 This separation is possible due to the presence of hemoglobin in RBCs, which in its deoxygenated form imparts a significant paramagnetic moment to the cell. White blood cells (WBCs) or all other cells from tissues are diamagnetic particles (due to the absence of hemoglobin). In order to be effective, the method requires generation of a high gradient magnetic field that is not presently employed in tissue engineering even though it can potentially be exploited for constructing tissues from RBC-containing stem cell sources.

In the third type of trapping, magnetic particles are selectively attached to cells and used in microfluidic devices for rare cell types separation,88, 89 and recently, in tissue engineering49, 90 [Fig. 2f]. Usually, these types of magnetic particles have a magnetic core and a coating tailored to bind to specific antibodies. There is a large range of magnetic particles (magnetite being the most common material used)–from nano to micro size used in such applications. There are two categories of particles: particles that will act as nonmagnetic as soon as the magnetic field is removed and are also small sized (the upper limit for iron being 42 nm); and larger-sized particles that will maintain a certain degree of magnetization even after the field has been removed. The first category is more attractive for tissue engineering.

A magnetic manipulation technique using magnetic nanoparticles seems to be a promising procedure, even if a strong magnetic field is required. Cells labeled with magnetic nanoparticles can be remotely manipulated by applying a magnetic field [Fig. 1c].91 For magnetic labeling of target cells, different solutions are used. Akiyama et al.92 used magnetic cationic liposomes that contain 10 nm magnetite nanoparticles to accumulate more magnetite nanoparticles into target cells. The same group proposed a cell patterning method93 using polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified magnetite nanoparticles for a coculture of mouse fibroblast NIH3T3 cells on a monolayer of HaCaT. This cell patterning method is quick and easily to perform.

Liu et al.94 proposed a permalloy microfluidic device for magnetic trapping of single cells. Ino et al.90 devised cell culture arrays using magnetic patterning and utilizing magnetic cationic liposomes for dynamic single cell analysis. For this application, gradients of the magnetic field were achieved using a pin holder and used for a 3D cell culture array.33 Ho et al.95 initially formed random arrangement of multicellular spheroids of HeLa cells after labeling them with paramagnetic particles. These spheroids were patterned rapidly with magnetic fields. The spheroids started fusing within few hours, forming a tissue construct. The paramagnetic particles remain in the cells after 3 weeks, as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. Akiyama et al.96 presented a method for the fabrication of cell sheets (monolayer of mouse myoblast C2C12) using magnetic fields and magnetic cationic liposomes. Magnetic microparticles were also used in tissue engineering for fabrication of 2D and 3D scaffolds with controllable pores. Uchida et al.97 used magnetic sugar particles [ferrite microparticles coated with fructose (sugar)] as pore forming agents in 3D biodegradable scaffolds. These particles are attracted by a magnetic force forming an assembled template for polymer casting. After polymer casting, the sugar was removed and the fabricated scaffold was used for human umbilical vein endothelial cell culture. Magnetic trapping employs a weak magnetic force and is contactless. The continuous exposure to the force (resulting in mechanical movement) might lead to a slight increase in temperature, which might cause unexpected physiological damage especially to sensitive cell or tissue types.32, 98

Acoustic trapping

Another method for contactless cell manipulation in microfluidic chips is using ultrasonic waves. Ultrasonic transducers generate waves, which subject the particles to a mechanical force. The force depends on the particle volume and frequency. The particles can be concentrated in either the nodes or antinodes of the periodic wave pattern [Fig. 2h]. A detailed description of the theory can be found in recent reviews.33, 99 Coakley et al.100 and Yeo et al.101 demonstrated early work involving ultrasonic waves in microfluidic devices. Recently, sonic waves were used for fast pumping (1–10 cm∕s) in microfluidic channels.102 A patterning technique using “acoustic tweezers” that utilizes standing surface acoustic wave (SAW) to manipulate and pattern cells and microparticles in a microfluidic chip was accomplished by Shi et al.103 The chip presents two interdigital transducers placed parallel to the microfluidic channel or in an orthogonal direction, allowing the alignment of the cells in line or other 2D patterns. A 3D ultrasonic cage has been used for characterization of HEK and B cells.104 The cage is simultaneously excited at two different frequencies corresponding to half-wave resonances in three orthogonal directions. By tuning the relative actuation voltages at the two frequencies, a 3D cell structure was achieved in the center of the cage with variation of transducers.105 Ravula et al.106 elucidated an interesting combination between ultrasound and DEP for particle trapping. Ultrasonic waves could prealign the particles while the DEP force then focuses them into a single line with high spatial resolution. In two different studies,107, 108 the authors demonstrated the use of SAW to guide cells into scaffolds.

The ultrasonic waves employed here are not detrimental to cell viability.109 COS-7 cells were exposed to ultrasonic waves (0.85 MPa pressure amplitude) in a PDMS-glass chip for 75 min with no change in the cell doubling time and maintenance of cell viability for 3 days. Bazou et al.110 investigated the influence of the physical environment (fluid flow rate, temperature, and possible cavitations) for trapped cells using sonic waves. The same group presented a long-term viability study on the proliferation of alginate-encapsulated 3D HepG2 aggregates previously formed in an ultrasound trap.111 The viability of the cells after 10 days cultivation was 70%–80%. More sensitive cell types and a detailed analysis on the effects of ultrasonic waves on cellular functions will be essential before wider acceptance in applications.

Laser∕optical trapping

Laser trapping or optical trapping uses a highly focused laser beam to trap and manipulate particles at very high precision [Fig. 1g].33 This technique was first developed by Ashkin in 1970 using a single laser beam.112 The momentum of the laser beam is transferred to the particle when it hits the object. The Gaussian profile of the laser beam will then cause the object to be drawn to the center of the beam, thereby trapping it.113 The original optical tweezers could trap objects ranging from a few angstroms to 10 μm 114 and exert forces up to hundreds of pN.115 Such force is ideal for many single cell and biopolymer manipulations. The ability of optical tweezers to manipulate cells has been exploited in tissue engineering to micropattern different cells types into tissue structures.116, 117 In this method, cells are pushed to the specific position one by one in the petri dish for culture with conventional methods. A microfluidic system can improve such tissue culture to control the culture microenvironment more precisely. In fact, the combination of optical tweezers and microfluidics had been used for single cell trapping and manipulating,118, 119 cell guiding,120 cell sorting,121, 122, 123 and biological particles analysis.124, 125

The single-beam optical tweezers require a separate laser beam for each manipulation object. This leads to the limited use of the technology in areas where multiple cell trapping is required in creating microtissue.33 Most developments focus on increasing the number of traps, trapping density, and flexibility in particles handling; such as scanning optical tweezers,126 diffractive optical tweezers127 or holographic optical tweezers,128 vertical cavity surface emitting laser (VCSEL),118 fiber bundle optical tweezers,129, 130 etc. Although most of these technologies started with nonbiological particle manipulations, some have progressed toward multiple cells trapping. For example, VCSEL array optical tweezers have been used for parallel trapping of yeast cells,131 red blood cells,131 and neuronal cells.118

More interestingly, studies have shown the ability to create complex biofilm or tissue structures in a microfluidic system in conjunction with optical trap arrays. In Mirsaidov’s work,132E.coli labeled with either green fluorescence protein or red fluorescence protein were delivered from two separate microfluidic channels. Cells were trapped using holographic optical tweezers at the assembly junctions and immobilized by poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogel. Moreover, they also precisely patterned the E.coli in 3D as well as creating an E.coli super array using a step-and-repeat method. Birkbeck et al. used VCSEL arrays trapping in PDMS microfluidic channels to coculture NIH 3T3 murine fibroblast and primary hepatocytes. The coculture was made up of a repeated chain of a single NIH 3T3 fibroblast and two rat primary hepatocytes, demonstrating precise control of laser trapping in cell trapping and patterning in tissue formation.133

Despite the versatility and precision offered by laser trapping, there are some drawbacks associated with it when dealing with cell culture. One of the critical limiting factors of using optical trapping in microfluidics is photodamage. Many mechanisms134, 135, 136 have been proposed, yet the origin remains unclear. Decreasing the intensity of the laser can decrease the extent of photodamage, but at the expense of the ability to trap large or irregular cells. Another way of minimizing photodamage is to use near infrared wavelengths;115 however, different cells respond differently to wavelength values. For instance, photodamage is the lowest at the wavelength of 830 nm for E.coli136 but at 970 nm for Chinese hamster ovary cells.137 Therefore, it is necessary to study the optical damage to the biological system on a case-by-case basis.133 Another drawback of laser trapping is the occurrence of local heating at the focus volume. The high intensity at the focus of the laser trap, 109–1012 W cm−2 compared to 10 mW cm−2 of bright sunlight, is the main cause of such heating.138 Liu and coworkers have measured the effect of the infrared light induced-local heating using human sperm cells, hamster ovary cells, and liposomes. The temperature increases as much as 10, 11.5, and 14.5 °C∕W, respectively.139, 140 Local heating is a serious issue in trapping cells as heat adversely affects enzyme activity and other sensitive cellular functions; also, steep thermal gradient might cause a convection current that disrupts laminar flow in the microfluidic channel. Therefore, there is much room to improve and potentially in combination with other physical and chemical trapping techniques.141, 142

Chemical trapping

Chemical trapping of cells within the microfluidic system falls into three categories: (1) cell patterning on a chemically modified surface, (2) a gel-based system: entrapment of cells in polymeric materials, and (3) a gel-free system: cell aggregation mediated by transient intercellular linker.

Chemical modification of microfluidic channel surface for cell immobilization

Most of the microfluidic-based cell culture platforms are fabricated using PDMS materials, which often results in nonspecific protein absorption due to the hydrophobic property of PDMS. It is therefore essential to modify the surface property of PDMS to facilitate proper cell and molecular attachment. The PDMS surface forming the microfluidic channels can be covalently modified with self assembled monolayer (SAM) and thick polymer tethering techniques to gain control over the microarchitecture, topography, surface feature size in the nanometer to micrometer scale, and chemical properties of the patterned surface.143 The microfabricated substrates have been patterned with polymers and proteins to facilitate cell attachment in a controlled and precise manner, which enables the construction of highly organized tissues [Fig. 2i].144, 145, 146, 147 Several groups have developed methods to micropattern biologically active molecules such as poly-L-lysine,148 fibronectin, and bovine serum albumin,149 for selective attachment of cells; e.g., human umbilical vein endothelial cells, human breast cancer cells, mouse fibroblasts, and primary rat cortical neurons onto the substrates. The patterned cells remain attached to the cell adhesion region and exhibit high cell viability throughout the culture period. Tan et al.150 demonstrated the use of 3D ECM biopolymers consisting of collagen, chitosan, and fibronectin for simultaneous patterning of multiple cell types in a microfluidic system. The incorporation of the biopolymer matrices in the microfluidic system helps in controlling the cellular interaction and migration patterns to better mimic the in vivo tissue functions. This platform can potentially be used for long-term in vitro biological experiments or tissue engineering applications. Liepmann’s group151 fabricated microstructured channel surface coated with antibodies against cell adhesion proteins to selectively capture and fractionate different cell types. This technique can guide the selective immobilization of desired cells on targeted adhesion substrates for biological research applications such as biosensors152 and tissue engineering and for fundamental studies of cell biology,153, 154 where cells need to be exposed to a controlled fluidic microenvironment.

Gel-based system for chemical trapping of cells

Microengineering techniques were adopted to create microfluidic networks in hydrogels. These hydrogels are equipped with high-resolution cellular feature sizes allowing 3D cell growth while maintaining fluidic access to the cells [Fig. 2j].28 The hydrogel is often immobilized with favorable cell-binding motifs that resemble those on the natural ECM in in vivo environments that interact with cells to regulate the cellular functions such as proliferation or differentiation.32 Various natural and synthetic hydrogels; for instance, calcium alginate155 and gelatin,156 have been used in microfluidic systems for cell encapsulation. Recently, cell laden agarose microfluidic hydrogels have been fabricated using a soft lithographic approach.157 Cells immobilized within the gel can form 3D artificial tissues with fine features.158, 159 PEG-based hydrogels can encapsulate a living cell array to create a local 3D microenvironment.149, 160 PEGs are used extensively because of their biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and ability to be customized by varying the chain length or chemically adding biological molecules.161 This helps to immobilize various types of cells that can attach, proliferate, and produce a matrix within the hydrogels.162, 163

There exist limitations with the use of hydrogels to form 3D cell culture. Mass transport of nutrients and oxygen to maintain cell viability is inefficient in large and dense hydrogels.164 In order to have temporal and spatial control of the distribution of soluble chemicals and fluids within microfluidic channels, the hydrogels must be spatially localized, which requires more complex design and operational steps of the microfluidic system.165, 166 Choi et al.167 directly fabricated functional microfluidic channels inside a calcium alginate 3D scaffold. These microfluidic channels enable an efficient exchange of solutes and quantitative control of the soluble factors experienced by cells in their 3D environment. This can potentially be used for growing thick viable tissue sections without core necrosis.167 Takeuchi’s group made used of uniformly sized self-assembling peptide to culture cells in 3D.20 The 3D nanofiber structure within the gel can be functionalized with different substrates such as cytokines to promote cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation. The use of agarose and matrigel for a perfusion based 3D cell culture system in a microfluidic platform has also been demonstrated.168, 169 These systems enable rapid perfusion of reagents through an array of 3D extracellular matrices with high spatial and temporal precision.

Gel-free system for chemical trapping of cells

To avoid gels completely and enable optimal cell-cell interactions, a gel-free method for seeding and culturing mammalian cells in 3D within a microfluidic channel was demonstrated by Ong et al. [Fig. 2k]43 3D multicellular constructs were formed with the help of trace amounts of a transient intercellular polymeric linker within the microfluidic channel. 3D cellular constructs formed this way re-established tight cell-cell junctions and epithelial cell polarity; this is ideal for the formation of 3D in vitro cellular models of epithelial tissues that are cell-dense and ECM-poor.

ENGINEERING MICROTISSUE CONSTRUCTS FOR APPLICATIONS

Microfluidic platforms for 3D cell culture are rapidly gaining importance in biomedical applications ranging from tissue engineering to drug toxicity or metabolism studies170, 171 and other aspects of the drug discovery process.155 Cell immobilization in a microfluidic system is becoming increasingly important as a way of creating artificial tissues.32 It can also be used for fundamental cell studies for understanding cell-cell interactions and cell responses to soluble stimuli.

Drug research

It is envisioned that in vitro cell-based assays would someday replace in vivo animal testing for drug research.172 In order to achieve this, the cell culture model should be able to mimic tissues’ in vivo behavior for which a “biologically-relevant” and “well-defined” cellular microenvironment is important so that the tested cells maintain all their phenotypic characteristics.6, 172In vitro culture of liver cells (hepatocytes) is important because many drug candidates fail in clinical studies; increasingly due to toxicity issues.171, 172 Many studies focus on trapping and culturing hepatocytes in microfluidic platforms. Powers et al.173, 174 described a 3D microarray bioreactor where they cultured primary hepatocytes for two weeks, forming viable tissue-like structures showing constant albumin secretion and urea genesis; and ultrastructure analysis of hepatocytes revealed bile canaliculi, numerous tight junctions, and glycogen storage. In another PDMS microbioreactor, rat hepatocytes attached to a porous PDMS membrane (5×5 μm pores) sandwiched between two perfusion chambers showed improved cell attachment, cell reorganization, albumin secretion, and ammonium removal.175 In a series of studies, Leclerc et al.176, 177, 178 fabricated chamber based microbioreactors with 3D cellular aggregations, enhancement in glucose consumption, and albumin secretion for fetal human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells. Prokop et al.179 presented a NanoLiterBioReactor in which hepatocytes were trapped by 3 μm sievelike features. Sivaraman et al.171 used a 3D microfabricated bioreactor system to make microtissue units of dimensions ∼2×10−5 cm3, which showed better gene expression, protein expression, and other biochemical activities as compared to 2D cultures. Co-cultures of hepatocytes with 3T3-J2 fibroblasts in a 64 (8×8) element array170 of microfluidic wells or on a microgrooved glass substrate180 exhibited steady levels of albumin and urea production. Kim et al.158 performed 3D culture of HepG2 cells inside a microfluidic channel with a peptide hydrogel puramatrix and showed toxicity with Triton X-100. The same group reported a matrigel-based microvalve-assisited patterning for 3D culture of HepG2 cells, which also included real-time monitoring of hepatotoxicity due to exposure to various concentrations of ethanol.181 Ma et al.182 developed a multilayer device for simultaneous characterization of the drug metabolites and to study the cytotoxicity related to drug metabolism. They employed a sol-gel human liver microsome (HLM) bioreactor for characterizing the metabolism of drug acetaminophen and its effect on HepG2 cells cytotoxicity as well as the drug interaction between acetaminophen and phenytoin.

Many microfluidic hepatocyte cultures can recapitulate part of the phenotypic functions of the liver and some with data on drug toxicity testing in vitro. We have reported a microfluidic 3D hepatocyte chip (Hepa Tox Chip) in which IC50 values of five drugs calculated from the chip correlate well with the in vivo toxicity data.42 The Hepa Tox Chip has eight parallel cell culture channels that are independently connected to outputs of a linear concentration gradient generator yielding eight different drug concentrations.

One challenge in drug screening models is mimicking the circulatory system of interacting with multiple organs in living organisms. In such cases, tests of a drug on two tissues separately would not necessarily reveal any toxicity.28 A chip with few channels and chambers each housing a different cell type was constructed to mimic the functions of a multiorgan organism.183 This μCCA (microcell culture analog device) pioneered by Shuler’s group is based on the structure of an appropriate physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model and emulates the body’s dynamic response to exposure to various drugs and chemicals. μCCA was designed based on parameters such as: the ratio of the chamber sizes, the liquid residence times in each compartment, the minimum number of cells to facilitate analysis of chemicals, and the hydrodynamic shear stress on the cells complying with physiological values.184 This μCCA has been used for many purposes. It has been hypothesized that using a combination of chemotherapeutics with a mixture of multidrug resistant (MDR) modulators (each with different side effects) may lead to useful treatment strategies.185 Sung et al.186 used the μCCA with 3D hydrogel to culture multiple cell types and measure the metabolism-dependent cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Shuler’s group recently developed a three-chamber μCCA for testing the toxicity of anticancer drug 5-fluorouracil and analyzed the results in light of a PK-PD model of the device.187 To capture the effects of multiple organ interactions, Zhang et al.45 proposed a multichannel 3-μFCCS (3D microfluidic cell culture system) with compartmentalized microenvironments for drug testing applications. The four different channels in the 3D-μFCCS contained four human cell types, C3A, A549, HK-2, and HPA, representing the liver, lung, kidney, and the adipose tissue, respectively.

Tissue fabrication

One major limitation in constructing large tissue is the diffusion distance (∼100–200 μm) for oxygen and nutrients to the cells in an artificial tissue construct. For a larger distance between culture media and cells, it is imperative that vascularization is necessary for a viable and functional tissue over a long duration.6, 188 Bornstein et al.189 developed a microfabricated PDMS scaffold and cultured endothelial cells for nearly 4 weeks with similar dimensions as capillaries. Roger Kamm’s group have established 3D angiogenesis and capillary morphogenesis models,190, 191 where human endothelial cells extend their filopodial projections, migrating into the collagen matrix and forming open tube∕lumen like structures when supplemented with pro-angiogenic factors. Angiogenesis was observed192 when culturing rat hepatocytes and rat endothelial cells on each microfluidic side wells with a collagen gel scaffold in between. The rat endocytes formed capillary structures that extended into the hepatocytes channel and further fluorescent dextran protein diffused across the gel scaffold, demonstrating secreted proteins by either of the cell types.

Bone and cartilage are two tissues in which shear stress and mechanical loading are critical. Mechanical interactions between cells are important for maintaining the chondroblastic and osteoblastic cells for successful cartilage and bone engineering, respectively.28, 193, 194 Compared to 2D culture, microfluidics support 3D culture with good cell-cell interactions and a fluidic network with physiological shear levels. Leclerc et al.195 cultured osteoblastic cells inside microdevices at different flow rates, yielding better alkaline phosphatase activity for cells cultured in device than 2D culture plates. Albrecht et al.196 showed 3D chondrocyte microorganization and its effect on matrix biosynthesis using their unique method of DEP cell patterning.

Cell polarization is an important aspect for tissues in the intestine and kidney, where transport is an important function. Kimura et al.197 used a polyester semipermeable membrane to culture Caco-2 cells and obtained the cell polarizability. The cells grew confluent and formed a tight monolayer within 9 days. With rhodamine 123, they showed the polarized transportation from the basolateral side to the apical side. Jang et al.198 similarly cultured rat inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells on a polyester membrane in a multilayer microfluidic device (kidney on chip). By applying a fluidic stress of nearly 1 dyn∕cm2 for 5 h, the authors could enhance cell polarization, cytoskeletal reorganization, and tight cell junction formation. The authors demonstrated the translocation of a membrane protein aquaporin-2 (AQP-2) from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane in AQP2-transfected MDCK cells, under the influence of hormones. All the above tissue culture models could be used for drug screening and the kidney chip could also be used as a disease model for nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) or edema.

Disease∕injury models

In vitro disease models have certain advantages over the in vivo models in cases when there is need for complete access to the lesions without ethical concerns or restrictions in animal research. Some disease models such as tumor models have explored microfluidic chips to enable precision control of drug access to the tumor niche defined by heterogeneous cell types and dynamic molecular signaling events. The malignant cells’ responses to therapeutic agents depend on short-order physical and chemical interactions with the cells.199 To provide simultaneous probes for many factors in a tumor model, microfluidics offer possibilities of large multiplexing of experiments and probing the dynamics, both inside and outside the cell.25, 200 Walsh et al.200 cultured LS174T colon carcinoma cell masses on a chip with viable spheroids over days. Cells inside the chamber became necrotic and apoptotic with the cells near to the flow appearing to be acidic and those farther away basic∕alkaline. Some other chips were developed to model cancer cell migration or metastasis: (i) tumor cells were deformed when migrating across a microchannel lined with human microvascular endothelial cells;201 (ii) invasion of cancer cells across a 3D matrix of basement membrane extract under the gradients of epidermal growth factor;202 and (iii) motility of cancer cells in 3D under the constrains of mechanical confinement with a matrix-free environment.203 Stroock et al.204 described the various engineering or biological challenges and opportunities for making a biomimetic microfluidic tumor model with a focus on embedding microvasculature structures.

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver due to viral infection. Chronic infection of the liver with hepatitis B∕C virus may lead to cirrhosis, primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma), and other end-stage liver diseases. Sodunke et al.205 designed a microfluidic device to study the replication of the hepatitis B virus by delivering the hepatitis B genome into HepG2 cells or primary hepatocytes using cationic lipids and recombinant adenoviruses, respectively, on chip.

Microfluidics offers a unique opportunity for neuron-based studies.206 Central nervous system (CNS) injuries or neurodegenerative diseases can be modeled using microfluidic chips. Jeon’s group developed a chip for many neuroscience applications.207, 208 The device has two compartments, separated by a physical barrier in which a number of microgrooves are embedded. These microgrooves allow the growth of neurites across the axonal side but not the cell bodies. Primary rat cortical and hippocampal neurons, which are standard CNS neuron populations, were successfully cultured in the device. The authors established a model for axonal injury by performing axotomy and isolating mRNA from axons; and screened compounds for stimulating the regenerative capacity of axons. Successful co-culturing of CNS neurons with oligodendrocytes on chip also enables the study of myelination and demyelinating diseases.

Cell-based biosensors

Cell-based biosensors are compact devices to detect a range of biochemical agents like toxicants, pathogens, pollutants, biomolecules, and drugs. Conventionally, small molecules, antibody- or nucleic acid-based assays serve as the direct readout parameters for detecting these biological or environmental agents. These methods rely on chemical properties or molecular recognition to identify a particular agent.209 In recent years, significant progress has been made in the characterization of drugs, pathogens, and toxicants’ impact on cultured cells in cellular or tissue biosensors.210 Cell-based biosensors can keep living cells under constant observation to study physiological changes when cells are subjected to stimuli.211 Microfluidics techniques can be used to improve the performance or functionality of these cell-based biosensors. The integration of microfluidics in cell-based biosensors helps to confine the preprocessed biomolecules or cells in a region of interest. Real-time bioassay sensing can be performed using a smaller sample volume, which will lead to higher sensitivity, rapid response, faster diagnosis, and less sample consumption, resulting in lower cost of the assays.212, 213 The mode of detecting the physiological changes in a microfluidic setting includes optical (e.g., fluorescent, luminescent, or colorimetric), plasmonic, mechanical, and electrical sensing;214 and in the future, functional genomics and proteomics might also be incorporated into the sensing mechanism.210

Cell density, viability, and cell-cell interaction can have a crucial effect on living cell-based sensors.28 Micropatterning techniques and 3D culture matrices were used to provide cells with structural integrity, enhanced cell attachment and suitable growth factors to mimic the in vivo niche. Morin et al.215 developed a microfluidic system to present predefined topographical features on the surface of a microelectrode array to control neuronal connectivity, which could be further developed into complex neuron-based biosensors for pharmacological screening. Patterned adhesion molecules on the surface of a microelectrode array can guide the growth of cultured cells. Long-term culture of the neuronal cells is achieved in the microwells linked by microchannels due to efficient delivery of soluble factors and fluid. Other groups have developed biosensors with cells cultured in a 3D-polymer matrix, including acrylamide derivatives, agarose, and collagen.216, 217, 218 Neural progenitor cells entrapped within the collagen matrices forming 3D microspheres can give rise to neuronal progeny that are responsive to environmental toxicants.218 This development can be further expanded to other cell types such as the immune cells and primary hepatocytes.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

The bottom-up modular approach of tissue engineering has generated much interest especially with the help of microfluidics-based 3D cell culture systems. The methods for trapping cells involving physical and chemical constraints allow cells to form 3D microstructures. These methods can recapitulate the extracellular microenvironment around the cells for engineering microtissue constructs; in some cases incorporating microvascular structures. The physical methods of cell trapping like DEP and laser are effective in cell seeding but limited in cell culture; and hence have been used in conjunction with chemical method.132, 196

As we construct larger tissue structures with microscale features, we realize that many intercellular tissue structures can only be constructed if we precisely control the cell shape and relative positions of certain subcellular mesoscale structures. There is an increasing interest to leverage on the micro and nanotechnologies to manipulate the cellular and subcellular functions.143 Therefore, future work should explore the mesoscale control of cell shapes for a group of cells in a microtissue construct. This would then ensure the proper development of the intercellular structures such as the bile canaliculi or sinusoids in case of hepatocytes and lacunae and canaliculi for housing the osteocyte body and osteocyte processes, respectively.193, 219 The bottom-up approach in tissue engineering also needs to be coupled with the top-down approach for solving the real life problems in therapeutics. This would be possible either by multiplexing of bottom-up microtissues or by incorporating bottom-up control features in the top-down scaffolds.15, 220 Further work would also need to address other issues such as the biodegradability and compatibility of biomaterials in certain in vivo applications.38

Tissue engineering is also defined as “applied developmental biology” and would gain immensely from the understanding of interactions between the cell receptors and their respective ligands in the surroundings.221 Two such ligands, integrins222 and cadherins,223 are being intensely investigated on how they can modulate the cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions leading to a multicellular entity called a tissue. These microtissue constructs can provide useful models for basic biology studies as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the Cellular and Tissue Engineering Laboratory, especially Dr. Yi-Chin Toh, for their valuable comments and scientific discussions. This work is supported in part by funding from the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, Biomedical Research Council, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) of Singapore; and grants from Jassen Cilag Sourcing Singapore (Grant No. R-185-000-182-592), Singapore-MIT Alliance Computational and Systems Biology Flagship Project (Grant No. C-382-641-001-091), SMART BioSyM, and the Mechanobiology Institute of Singapore (Grant No. R-714-001-003-271) for H.Y. D.C. and W.H.T. are NGS research scholars and X.M. is a NUS Graduate Research Scholar.

References

- Langer R. and Vacanti J., Science 260, 920 (1993). 10.1126/science.8493529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaght M. J. and Reyes J., Tissue Eng. 7, 485 (2001). 10.1089/107632701753213110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith L. G. and Naughton G., Science 295, 1009 (2002). 10.1126/science.1069210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang V. L. and Bhatia S. N., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 56, 1635 (2004). 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. and Vacanti J., Sci. Am. 280, 86 (1999). 10.1038/scientificamerican0499-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A., Vacanti J. P., and Langer R., Sci. Am. 300, 64 (2009). 10.1038/scientificamerican0509-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaght M. J., Jaklenec A., and Deweerd E., Tissue Eng. Part A 14, 305 (2008). 10.1089/tea.2007.0267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A. and Langer R., Biomaterials 28, 5087 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol J. W. and Khademhosseini A., Soft Matter 5, 1312 (2009). 10.1039/b814285h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister S. J., Nature Mater. 5, 590 (2006). 10.1038/nmat1683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutmacher D. W., Biomaterials 21, 2529 (2000). 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00121-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston T., Ducheyne P., and Garino J., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 62, 1 (2002). 10.1002/jbm.10157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese D., Deshpande M., Xu T., Kesari P., Ohri S., and Boland T., J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 129, 470 (2005). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N., Shimizu T., Yamato M., and Okano T., Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 19, 3089 (2007). 10.1002/adma.200701978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Causa F., Netti P. A., and Ambrosio L., Biomaterials 28, 5093 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. A., Lo E., Ali S., and Khademhosseini A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9522 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0801866105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan A. P. and Sefton M. V., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11461 (2006). 10.1073/pnas.0602740103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm J. M., Ittner L. M., Born W., Djonov V., and Fussenegger M., J. Biotechnol. 121, 86 (2006). 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner Z. J. and Bertozzi C. R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4606 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0900717106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda Y., Morimoto Y., and Takeuchi S., Langmuir 26, 2645 (2010). 10.1021/la902827y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S., Shimizu T., Yamato M., and Okano T., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 60, 277 (2008). 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L'Heureux N., Paquet S., Labbe R., Germain L., and Auger F. A., FASEB J. 12, 47 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov V., Boland T., Trusk T., Forgacs G., and Markwald R. R., Trends Biotechnol. 21, 157 (2003). 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00033-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J., Becker M., Tombrink S., and Manz A., Anal. Chem. 80, 4403 (2008). 10.1021/ac800680j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesides G. M., Nature (London) 442, 368 (2006). 10.1038/nature05058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyvantsson I. and Beebe D. J., Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1, 423 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velve-Casquillas G., Le Berre M., Piel M., and Tran P. T., Nanotoday 5, 28 (2010). 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ali J., Sorger P. K., and Jensen K. F., Nature (London) 442, 403 (2006). 10.1038/nature05063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott A., Nature (London) 424, 870 (2003). 10.1038/424870a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampaloni F., Reynaud E. G., and Stelzer E. H., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 839 (2007). 10.1038/nrm2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh Y. C., Zhang C., Zhang J., Khong Y. M., Chang S., Samper V. D., van Noort D., Hutmacher D. W., and Yu H. R., Lab Chip 7, 302 (2007). 10.1039/b614872g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johann R. M., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 385, 408 (2006). 10.1007/s00216-006-0369-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J., Evander M., Hammarstrom B., and Laurell T., Anal. Chim. Acta 649, 141 (2009). 10.1016/j.aca.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R. H., Gabel C. V., Chan S. S., Austin R. H., Brody J. P., and Winkelman J. W., Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2149 (1997). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Lin H., Liu J. Q., Balic M., Datar R., Cote R. J., and Tai Y. C., J. Chromatogr. A 1162, 154 (2007). 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelley A. M., Kirak O., Suh H., Jaenisch R., and Voldman J., Nat. Methods 6, 147 (2009). 10.1038/nmeth.1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo D., Aghdam N., and Lee L. P., Anal. Chem. 78, 4925 (2006). 10.1021/ac060541s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. J., Cho Y. H., Gu J. M., Kim J., and Oh Y. S., Lab Chip 11, 115 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00134a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. S., Li C. W., and Yang J., Anal. Chem. 74, 3991 (2002). 10.1021/ac025536c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. H. and Takeuchi S., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1146 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0606625104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. H. and Takeuchi S., Lab Chip 8, 259 (2008). 10.1039/b714573j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh Y. -C., Lim T. C., Tai D., Xiao G., van Noort D., and Yu H., Lab Chip 9, 2026 (2009). 10.1039/b900912d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S. M., Zhang C., Toh Y. C., Kim S. H., Foo H. L., Tan C. H., van Noort D., Park S., and Yu H., Biomaterials 29, 3237 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Chia S. -M., Ong S. -M., Zhang S., Toh Y. -C., van Noort D., and Yu H., Biomaterials 30, 3847 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Zhao Z., Rahim N. A. A., van Noort D., and Yu H., Lab Chip 9, 3185 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A., Yeh J., Jon S., Eng G., Suh K. Y., Burdick J. A., and Langer R., Lab Chip 4, 425 (2004). 10.1039/b404842c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A., Yeh J., Eng G., Karp J., Kaji H., Borenstein J., Farokhzad O. C., and Langer R., Lab Chip 5, 1380 (2005). 10.1039/b508096g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu D. T., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 17 (2007). 10.1007/s00216-006-0611-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. M., Lai Y. S., Liu H. P., Chen C. Y., and Wo A. M., Anal. Chem. 80, 8937 (2008). 10.1021/ac800972t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz B. R., Chen J., and Schwartz D. T., Anal. Chem. 78, 5429 (2006). 10.1021/ac060555y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, 1995). 10.1017/CBO9780511574498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Xu G. L., Samper V., and Tay F. E. H., J. Micromech. Microeng. 15, 494 (2005). 10.1088/0960-1317/15/3/009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Talary M. S., and Lee R. S., IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 22, 43 (2003). 10.1109/MEMB.2003.1266046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham S. N. and Sweatman D. R., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 41, 175503 (2008). 10.1088/0022-3727/41/17/175503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. B. and Singh A. K., Anal. Chem. 75, 4724 (2003). 10.1021/ac0340612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Xu G. L., Loe F. C., Ong P. L., and Tay F. E. H., Electrophoresis 28, 1107 (2007). 10.1002/elps.200600431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewpiriyawong N., Yang C., and Lam Y. C., Biomicrofluidics 2, 034105 (2008). 10.1063/1.2973661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen C. P., Huang C. T., and Shih H. Y., Microsystem Technologies-Micro-and Nanosystems-Information Storage and Processing Systems 16, 1097 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Xu G. L., Ong P. L., and Leck K. J., J. Micromech. Microeng. 17, S128 (2007). 10.1088/0960-1317/17/7/S10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou P. Y., Ohta A. T., and Wu M. C., Nature (London) 436, 370 (2005). 10.1038/nature03831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang H., Lee D. H., Choi W. J., and Park J. K., Biomicrofluidics 3, 014103 (2009). 10.1063/1.3086600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markx G. H., Dyda P. A., and Pethig R., J. Biotechnol. 51, 175 (1996). 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01617-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S., Washizu M., and Nanba T., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 25, 732 (1989). 10.1109/28.31255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voldman J., Toner M., Gray M. L. and Schmidt M. A., J. Electrost. 57, 69 (2003). 10.1016/S0304-3886(02)00120-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Yu L. M., Tay F. E. H., and Chen B. T., Sens. Actuators B 129, 491 (2008). 10.1016/j.snb.2007.11.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Lu J., Marukenko S. A., Monuki E. S., Flanagan L. A., and Lee A. P., Electrophoresis 30, 782 (2009). 10.1002/elps.200800637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. M., Iliescu C., Xu G. L., and Tay F. E. H., J. Microelectromech. Syst. 16, 1120 (2007). 10.1109/JMEMS.2007.901136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Yu L. M., Xu G. L., and Tay F. E. H., J. Microelectromech. Syst. 15, 1506 (2006). 10.1109/JMEMS.2006.883567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. W., Rosset S., Niklaus M., Adleman J. R., Shea H., and Psaltis D., Lab Chip 10, 783 (2010). 10.1039/b917719a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I. F., Chang H. C., and Hou D., Biomicrofluidics 1, 021503 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z., Mazur J., and Chang H. C., Biomicrofluidics 3, 044108 (2009). 10.1063/1.3257857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z. W., Lee S., and Ahn C. H., IEEE Sens. J. 8, 527 (2008). 10.1109/JSEN.2008.918907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay F. E. H., Yu L. M., Pang A. J., and Iliescu C., Electrochim. Acta 52, 2862 (2007). 10.1016/j.electacta.2006.09.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Tresset G., and Xu G. L., Biomicrofluidics 3, 044104 (2009). 10.1063/1.3251125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A., Morgan H., Green N. G., and Castellanos A., J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 31, 2338 (1998). 10.1088/0022-3727/31/18/021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan L. A., Lu J., Wang L., Marchenko S. A., Jeon N. L., Lee A. P., and Monuki E. S., Stem Cells 26, 656 (2008). 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldman J., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8, 425 (2006). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsong T. Y., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1113, 53 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 493 (1995). 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkleman A., Gudiksen K. L., Ryan D., Whitesides G. M., Greenfield D., and Prentiss M., Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2411 (2004). 10.1063/1.1794372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T., Yamato M., and Nara A., Langmuir 20, 572 (2004). 10.1021/la035768m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijs M. A. M., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 1, 22 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Pamme N., Lab Chip 6, 24 (2006). 10.1039/b513005k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T., Sato Y., Kimura F., Iwasaka M., and Ueno S., Langmuir 21, 830 (2005). 10.1021/la047517z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu C., Xu G. L., Barbarini E., Avram M., and Avram A., Microsystem Technologies-Micro-and Nanosystems-Information Storage and Processing Systems 15, 1157 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ito A., Akiyama H., Kawabe Y., and Kamihira M., J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 288 (2007). 10.1263/jbb.104.288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K. H. and Frazier A. B., Lab Chip 6, 265 (2006). 10.1039/b514539b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis D. W., Riehn R., Austin R. H., and Sturm J. C., Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5093 (2004). 10.1063/1.1823015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng T., Prentiss M., and Whitesides G. M., Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 461 (2002). 10.1063/1.1436282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ino K., Okochi M., Konishi N., Nakatochi M., Imai R., Shikida M., Ito A., and Honda H., Lab Chip 8, 134 (2008). 10.1039/b712330b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J., Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 139 (2008). 10.1038/nnano.2008.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H., Ito A., Kawabe Y., and Kamihira M., Biomed. Microdevices 11, 713 (2009). 10.1007/s10544-009-9284-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H., Ito A., Kawabe Y., and Kamihira M., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 92A, 1123 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Dechev N., Foulds I. G., Burke R., Parameswaran A., and Park E. J., Lab Chip 9, 2381 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho V. H. B., Muller K. H., Barcza A., Chen R. J., and Slater N. K. H., Biomaterials 31, 3095 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H., Ito A., Kawabe Y., and Kamihira M., Biomaterials 31, 1251 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Oura H., Ikeda S., Arai F., Negoro M., and Fukuda T., International Symposium on Micro-NanoMechatronics and Human Science, 2007.

- Ubeda A., Trillo M. A., Chacon L., Blanco M. J., and Leal J., Bioelectromagnetics (N.Y.) 15, 385 (1994). 10.1002/bem.2250150503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell T., Petersson F., and Nilsson A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 492 (2007). 10.1039/b601326k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coakley W. T., Bazou D., Morgan J., Foster G. A., Archer C. W., Powell K., Borthwick K. A. J., Twomey C., and Bishop J., Colloids Surf., B 34, 221 (2004). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo L. Y., Hou D., Maheshswari S., and Chang H. C., Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 233512 (2006). 10.1063/1.2212275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo L. Y. and Friend J. R., Biomicrofluidics 3, 012002 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Ahmed D., Mao X., Lin S. -C. S., Lawit A., and Huang T. J., Lab Chip 9, 2890 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manneberg O., Vanherberghen B., Svennebring J., Hertz H. M., Onfelt B., and Wiklund M., Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 063901 (2008). 10.1063/1.2971030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svennebring J., Manneberg O., Skafte-Pedersen P., Bruus H., and Wiklund M., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 103, 323 (2009). 10.1002/bit.22255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravula S. K., Branch D. W., James C. D., Townsend R. J., Hill M., Kaduchak G., Ward M., and Brener I., Sens. Actuators B 130, 645 (2008). 10.1016/j.snb.2007.10.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bok M., Li H. Y., Yeo L. Y., and Friend J. R., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 103, 387 (2009). 10.1002/bit.22243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Friend J. R., and Yeo L. Y., Biomaterials 28, 4098 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultstrom J., Manneberg O., Dopf K., Hertz H. M., Brismar H., and Wiklund M., Ultrasound Med. Biol. 33, 145 (2007). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazou D., Kuznetsova L. A., and Coakley W. T., Ultrasound Med. Biol. 31, 423 (2005). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazou D., Coakley W. T., Hayes A. J., and Jackson S. K., Toxicol. In Vitro 22, 1321 (2008). 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkin A., Phys. Rev. Lett. 24, 156 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- Molloy J. and Padgett M., Contemp. Phys. 43, 241 (2002). 10.1080/00107510110116051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkin A. and Dziedzic J., Science 235, 1517 (1987). 10.1126/science.3547653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggee C., Anal. Chem. 81, 16 (2009). 10.1021/ac8023203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmias Y., Schwartz R., Verfaillie C., and Odde D., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 92, 129 (2005). 10.1002/bit.20585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmias Y. and Odde D., Nat. Protoc. 1, 2288 (2006). 10.1038/nprot.2006.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan M., Pisanic T., Scheel J., Barlow C., Esener S., and Bhatia S., Langmuir 19, 1532 (2003). 10.1021/la0261848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arai F., Ng C., Maruyama H., Ichikawa A., El-Shimy H., and Fukuda T., Lab Chip 5, 1399 (2005). 10.1039/b502546j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugiran S., Gétin S., Fedeli J., Colas G., Fuchs A., Chatelain F., and Derouard J., Opt. Express 13, 6956 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.006956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai F., Ichikawa A., Ogawa M., Fukuda T., Horio K., and Itoigawa K., Electrophoresis 22, 283 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M., Spalding G., and Dholakia K., Nature (London) 426, 421 (2003). 10.1038/nature02144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. M., Tu E., Raymond D. E., Yang J. M., Zhang H., Hagen N., Dees B., Mercer E. M., Forster A. H., Kariv I., Marchand P. J., and Butler W. F., Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 83 (2005). 10.1038/nbt1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiter C., Gjoni M., Hovius R., Martinez K., Segura J., and Vogel H., ChemBioChem 6, 2187 (2005). 10.1002/cbic.200500216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson E., Enger J., Nordlander B., Erjavec N., Ramser K., Goksör M., Hohmann S., Nyström T., and Hanstorp D., Lab Chip 7, 71 (2007). 10.1039/b613650h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K., Koshioka M., Misawa H., Kitamura N., and Masuhara H., Opt. Lett. 16, 1463 (1991). 10.1364/OL.16.001463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne E. and Grier D., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 69, 1974 (1998). 10.1063/1.1148883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne E., Spalding G., Dearing M., Sheets S., and Grier D., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 72, 1810 (2001). 10.1063/1.1344176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J. M., Biran I., and Walt D. R., Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4289 (2004). 10.1063/1.1753062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberale C., Minzioni P., Bragheri F., De Angelis F., Di Fabrizio E., and Cristiani I., Nat. Photonics 1, 723 (2007). 10.1038/nphoton.2007.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan M., Wang M., Ozkan C., Flynn R., and Esener S., Biomed. Microdevices 5, 61 (2003). 10.1023/A:1024467417471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsaidov U., Scrimgeour J., Timp W., Beck K., Mir M., Matsudaira P., and Timp G., Lab Chip 8, 2174 (2008). 10.1039/b807987k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkbeck A., Flynn R., Ozkan M., Song D., Gross M., and Esener S., Biomed. Microdevices 5, 47 (2003). 10.1023/A:1024463316562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneckenburger H., Hendinger A., Sailer R., Gschwend M., Strauss W., Bauer M., and Schuetze K., J. Biomed. Opt. 5, 40 (2000). 10.1117/1.429966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König K., Liang H., Berns M., and Tromberg B., Opt. Lett. 21, 1090 (1996). 10.1364/OL.21.001090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman K., Chadd E., Liou G., Bergman K., and Block S., Biophys. J. 77, 2856 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77117-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Vu K., Krishnan P., Trang T., Shin D., Kimel S., and Berns M., Biophys. J. 70, 1529 (1996). 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79716-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman K. and Nagy A., Nat. Methods 5, 491 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Cheng D., Sonek G., Berns M., Chapman C., and Tromberg B., Biophys. J. 68, 2137 (1995). 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80396-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Sonek G., Berns M., and Tromberg B., Biophys. J. 71, 2158 (1996). 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79417-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman E. J. G., Gittes F., and Schmidt C. F., Biophys. J. 84, 1308 (2003). 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74946-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol Y., Carpenter A., and Perkins T., Opt. Lett. 31, 2429 (2006). 10.1364/OL.31.002429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai T. A., Med. Eng. Phys. 22, 595 (2000). 10.1016/S1350-4533(00)00087-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. S., Takayama S., Ostuni E., Ingber D. E., and Whitesides G. M., Biomaterials 20, 2363 (1999). 10.1016/S0142-9612(99)00165-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S., McDonald J. C., Ostuni E., Liang M. N., Kenis P. J., Ismagilov R. F., and Whitesides G. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5545 (1999). 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch A., Ayon A., Hurtado O., Schmidt M. A., and Toner M., J. Biomech. Eng. 121, 28 (1999). 10.1115/1.2798038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong I. and Ho C. M., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 7, 291 (2009). 10.1007/s10404-009-0443-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. W., Taylor A. M., Tu C. H., Cribbs D. H., Cotman C. W., and Jeon N. L., Lab Chip 5, 102 (2005). 10.1039/b403091e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A., Suh K. Y., Jon S., Eng G., Yeh J., Chen G. J., and Langer R., Anal. Chem. 76, 3675 (2004). 10.1021/ac035415s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. and Desai T. A., Tissue Eng. 9, 255 (2003). 10.1089/107632703764664729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. C., Lee L. P., and Liepmann D., Lab Chip 5, 64 (2005). 10.1039/b400455h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrksich M. and Whitesides G. M., Trends Biotechnol. 13, 228 (1995). 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)88950-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mrksich M. and Whitesides G. M., Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 25, 55 (1996). 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhvi R., Kumar A., Lopez G. P., Stephanopoulos G. N., Wang D. I., Whitesides G. M., and Ingber D. E., Science 264, 696 (1994). 10.1126/science.8171320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabodi M., Choi N. W., Gleghorn J. P., Lee C. S., Bonassar L. J., and Stroock A. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13788 (2005). 10.1021/ja054820t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paguirigan A. and Beebe D. J., Lab Chip 6, 407 (2006). 10.1039/b517524k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y., Rubin J., Deng Y., Huang C., Demirci U., Karp J. M., and Khademhosseini A., Lab Chip 7, 756 (2007). 10.1039/b615486g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Yeon J. H., and Park J. K., Biomed. Microdevices 9, 25 (2007). 10.1007/s10544-006-9016-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. and Desai T. A., Biomaterials 25, 1355 (2004). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht D. R., Tsang V. L., Sah R. L., and Bhatia S. N., Lab Chip 5, 111 (2005). 10.1039/b406953f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppas N. A., Bures P., Leobandung W., and Ichikawa H., Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 50, 27 (2000). 10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00090-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin A. S. and West J. L., FASEB J. 16, 751 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hern D. L. and Hubbell J. A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 39, 266 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A. P. and Tien J., Lab Chip 7, 720 (2007). 10.1039/b618409j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figallo E., Cannizzaro C., Gerecht S., Burdick J. A., Langer R., Elvassore N., and Vunjak-Novakovic G., Lab Chip 7, 710 (2007). 10.1039/b700063d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh Y. C., Ng S., Khong Y. M., Samper V., and Yu H., Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 3, 169 (2005). 10.1089/adt.2005.3.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N. W., Cabodi M., Held B., Gleghorn J. P., Bonassar L. J., and Stroock A. D., Nature Mater. 6, 908 (2007). 10.1038/nmat2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. H., Huang S. B., Cui Z., and Lee G. B., Biomed. Microdevices 10, 309 (2008). 10.1007/s10544-007-9138-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lii J., Hsu W. J., Parsa H., Das A., Rouse R., and Sia S. K., Anal. Chem. 80, 3640 (2008). 10.1021/ac8000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane B. J., Zinner M. J., Yarmush M. L., and Toner M., Anal. Chem. 78, 4291 (2006). 10.1021/ac051856v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]