Abstract

The mammalian epidermis is a self-renewing stratified squamous epithelium. Its basal cell layer contains proliferating keratinocytes that exit the cell cycle when they move into the suprabasal compartment. These cells activate a gene differentiation program aimed at building a protective epidermal barrier as they move toward the surface, successively going through the spinous and granular layers. At the completion of this process, the keratinocytes become enucleated and form the cornified layer, the surface layer of the skin. The highly cross-linked protein–lipid envelope and extracellular lipids in the cornified layer along with cell–cell adhesions in the granular layer are required for an effective epidermal barrier. Transcriptional mechanisms are critical for the formation of the epidermal barrier, and in this chapter, we describe methods to evaluate the role of a transcription factor (TF) in epidermal differentiation. To identify direct target genes of a TF, we propose a combination of bioinformatics and experimental approaches. The ultimate goal of these approaches is to understand the mechanisms whereby a TF regulates epidermal barrier formation.

Keywords: Epidermal barrier, Keratinocytes, Time course microarray analysis, Electromobility shift assays, Chromatin immunoprecipitation, Luciferase

1. Introduction

The mammalian epidermis consists of multiple layers of epithelial cells at different stages of differentiation. The proliferating progenitor cells are found in the basal layer; these cells are constantly moving toward the skin's surface, progressively differentiating as they move along, ultimately reaching the outermost cornified layer which is continuously sloughed off. The cornified envelope and lipids of the cornified layer as well as the junctions between keratinocytes in the deeper layers constitute key elements of the epidermal barrier; their disruption results in several skin diseases (1). This differentiation process is tightly regulated by a battery of TFs that either suppress the differentiation program, thus maintaining the undifferentiated state of basal cell layer keratinocytes, or activate it, thus promoting differentiation in the supra-basal layers (2, 3).

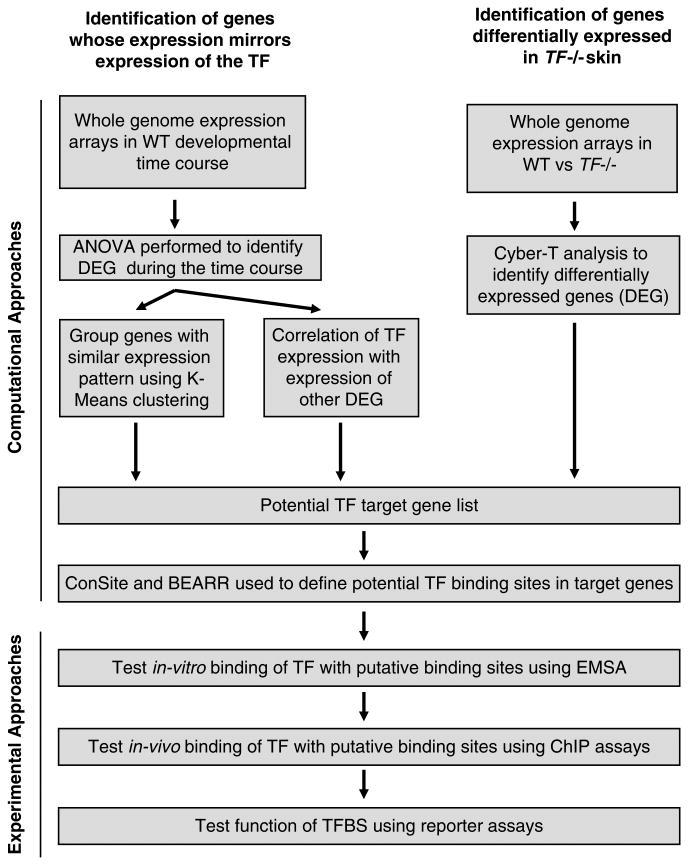

Here, we describe selective methods to investigate the role of a transcription factor (TF) in epidermal differentiation (Fig. 1). An early step to determine the role of a TF is to mutate the encoding gene in mice. Once a knockout mouse is available, a range of experiments can be performed to elucidate the gene program regulated by the TF.

Fig. 1.

A schematic outline of methods to evaluate potential gene targets of a transcription factor in skin epidermal differentiation. TF transcription factor, DEG differentially expressed genes, BEARR Batch extraction and analysis of cis-regulatory regions, EMSA electromobility shift assay, ChIP chromatin immunoprecipitation, TFBS transcription factor binding site.

To identify genes that are regulated by the TF in skin, gene expression microarray experiments can be performed, comparing knockout and wild-type (WT) mouse skin. This data can be analyzed using Cyber-T (4), a publicly available program that defines statistically significantly differentially expressed genes in the knockout versus wild-type skin. Some of the differentially regulated genes may be direct targets of the TF.

To help identify genes directly regulated by a TF, a developmental time course microarray experiment can be performed using back skin from wild-type mice sampled over the differentiation process (5). Similar time course experiments can be done with in vitro cell models for epidermal differentiation, and we have used this approach to study transcriptional regulation in other epithelia such as hair follicles (6, 7) and bladder (5). The data are imported in Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) (8, 9) and analyzed by ANOVA to identify those genes whose expression changes significantly over the time course. The significantly altered genes can then be grouped using K-Means clustering to define which genes share a similar pattern of expression over the time course. Genes that cluster with the TF in question are more likely to be its targets, especially if they are also differentially regulated in the TF-mutated skin. Alternatively, one can use correlation analysis to identify those genes that show a strong positive or negative correlation in expression with the TF; if the TF acts as a repressor, target genes may show complementary patterns of expression.

The candidate target genes identified as described above are then analyzed for the presence of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) using two publicly available programs ConSite (10) and BEARR (Batch extraction and analysis of cis-regulatory regions) (11). This approach assumes that the binding site for the TF has been determined. Presence of a conserved TFBS in the upstream region or first intron of a gene enhances the probability that the gene in question is a direct target of the TF.

The candidate TFBS can then be tested for TF binding in vitro using electro mobility shift assays (EMSA). This method will also determine the in vitro binding affinities of each site.

To determine whether the TF binds the candidate site in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays are performed using primary human or mouse keratinocytes and a specific antibody against the TF.

To demonstrate that these sites are functional, the gene regulatory region in question is linked to a reporter gene, and the ability of the TF to activate transcription from a WT and TFBS-mutated reporter is evaluated. A more rigorous in vivo test of a TFBS is to generate BAC transgenic mice expressing GFP under the control of a wild-type and mutated promoter (12, 13). This is not discussed here, as it is beyond the scope of this chapter.

While this series of experiments will not comprehensively identify all target genes of a TF, the proposed approach should allow the identification of multiple direct TF targets, thus providing insights into the mechanisms whereby a TF regulates epidermal differentiation and barrier formation.

2. Materials

2.1. Gel Shift Assays

ATP, [γ 32P]-EasyTide, 250 μCi (Perkin Elmer; Cat. No. BLU502Z250UC).

T4 polynucleotide Kinase and buffer (Promega; Cat. No. M4101) Store at −20°C.

Loading Dye: 10 ml of 100% Glycerol, 2 ml of 0.5 M EDTA, 1% bromo-phenol blue.

50 mM NACl in TE buffer.

5× Gel shift Buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 250 mM KCl, 25% glycerol. Aliquot and store at −20°C.

10 mg/ml Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Store at −20°C.

100 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT). Aliquot and store at −20°C. Avoid freeze–thawing.

Poly (dI-dC)·Poly(dI-dC) (1 µg/µl) (EMD chemicals; Cat. No. 71294-125ul) Store at −20°C.

10% native gel: 50 ml Protogel, 50 ml 1× TBE, 600 µl 10% APS, 60 µl TEMED.

6% native gel: 20 ml Protogel, 50 ml 1× TBE, 10 ml 50% Glycerol, 20 ml Water, 600 µl 10% APS, 60 µl TEMED.

Scintillation Fluid – Cytoscint (Fisher; Cat. No. BP458-4).

2.2. Chromatin Immuno-precipitation Assays

Aprotinin-5 mg (Sigma; Cat. No. A11535MG). Make stock solution at 10 mg/ml in 0.01 M HEPES pH 8.0, aliquot as 10-µl volumes in PCR tubes, and store at −20°C. Dilute at 1:100 prior to use.

Leupeptin-5 mg (Sigma; Cat. No. L2884-5MG). Make stock solution at 10 mg/ml in water. Aliquot as 10-µl volumes in PCR tubes and store at −20°C. Dilute at 1:1,000 prior to use.

PMSF-1G (Sigma; Cat. No. 78830-1G). Make stock solution at 100 mM in ethanol. Aliquot as 10-μl volumes in PCR tubes and store at −20°C. Dilute at 1:1,000 prior to use.

Pansorbin cells, lyophilized (Staph A cells). Reconstituted in distilled water (Calbiochem; Cat. No. 507862).

IgG from Rabbit serum, lyophilized (Sigma; Cat. No. I5006-10MG).

RNA polymerase II 8WG16 Monoclonal Antibody (Covance; Cat. No. MMS-126R).

GenElute PCR cleanup kit (Sigma; Cat. No. NA1020-1KT).

37% Formaldehyde. Use at a final concentration of 1% formaldehyde. It can be directly added to the media.

2.5 M Glycine. Store at RT. Use at a final concentration of 0.125 M.

10× PBS (Phosphate-buffered saline).

5 M NaCl. Store at RT.

10 mg/ml of Salmon sperm DNA (Invitrogen; Cat. No. 15632-011).

Bioruptor-sonicator (Diagenode).

Denville Taq Polymerase and buffer (Denville; Cat. No. CB4050-1).

2.5 mM dNTP Mix (Fermentas; Cat. No. R0192).

Dialysis Buffer (DB):2 mM EDTA, 50mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0.

SDS Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris–Cl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS.

ChIP Dilution Buffer: 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton × 100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, and 167 mM NaCl.

Low-Salt wash buffer: 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton × 100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl.

High-Salt wash buffer: 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton × 100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl.

LiCl wash buffer: 0.25 M LiCl, 1% IGEPAL-CA630, 1% deoxycholic acid (sodium salt), 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris pH 8.1.

TE: 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0.

2.3. Reporter Assays

Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Cat. No. 11668-019).

Opti-MEM® I Reduced-Serum Medium (Invitrogen, Cat. No. 31985-070).

E-Low calcium medium (14). Add 1.2 mM calcium to this media if you need to use differentiated cells for ChIP assays.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega; Cat. No. E1910).

pGL3-Basic vector (Promega; Cat. No. E1751).

BD falcon round bottom tube (Cat. No. 352052)-For use in the luminometer.

1× PLB: Add 1 volume of 5× Passive Lysis Buffer (PLB) to 4 volumes of distilled water. Mix well. Store at 4°C (≤1 month).

LAR II: The lyophilized Luciferase Assay Substrate (LAR) is resuspended in 10 ml of Luciferase Assay Buffer II (for Cat. No. E1910, E1960). Store at −20°C (≤1 month) or −70°C (≤1 year).

Stop & Glo Reagent: Dilute the 50× reagent to 1× using the Stop & Glo Buffer. Make smaller amount as needed. Store at −20°C for 15 days.

3. Methods

3.1. Computational Approaches

3.1.1. Differential Gene Expression Analysis Using Cyber-T

Cyber-T is a statistical program with a Web interface (http://cybert.microarray.ics.uci.edu) that can be conveniently used on microarray data for the identification of statistically significant differentially expressed genes (4). The statistical analyses carried out by Cyber-T is based on either simple t-tests that use the observed variance of replicate gene measurements across replicate experiments, or regularized t-tests that use a Bayesian estimate of the variance among gene measurements within an experiment. Cyber-T is also able to compute posterior probability of differential expression (PPDE) based on the modeling of p-value distributions which is an indicator of an experiment-wide false discovery rate. It has been shown to provide a higher confidence list of differentially regulated genes compared to many other programs used for analyzing expression microarray data (15).

Cyber-T input

It is recommended to include at least three replicates of control and test samples to allow for statistical inference. In order to run the data through Cyber-T, the Probe ID and the expression values must be separated from the additional annotation data which is provided with your array results and stored as a tab delimited text file (the annotation data is placed back in the Cyber-T output file). Absent genes (raw expression values below ∼100 for Affymetrix chips) can be removed in Excel using the “IF” command and scoring for each gene in each sample as 1 or 0 if its expression value is present or absent, respectively. A gene is included as present if it has expression values over ∼100 in all three replicates in either the control or experimental samples. The tab delimited text file of Probe IDs and raw expression values of present genes are used as the input text file for this program. Since most microarrays are single dye experiments, you should choose the statistical analysis for “Control versus Experimental Data” and upload the input text file. After filling in the column information in the input file, make sure to check the button to perform PPDE analysis. A default value of “10” can be chosen for Bayesian standard deviation estimation.

Cyber-T output

Once the Cyber-T is run, the output provides a score of all genes which can then be exported into an Excel sheet. For easier processing of data, you can delete most of the columns in the file which shows the output of Cyber-T algorithm's various calculations. The columns you want to keep are the Probe set IDs, all experimental and control values, Bayes P or Bayes lnP, Fold, and PPDE values. After this is completed, the additional data you removed before running the Cyber-T program, including gene symbol and Gene annotation, can be added back (make sure that your sorting is correct to keep the appropriate information with its correct Probe ID or you can use Office Access to combine the two lists). All genes that are present and have a p-value ≤ 0.01 are the statistically significant differentially expressed genes. You can take advantage of the PPDE value and also use more stringent p-values depending on the confidence you wish to have in the differentially expressed genes (see Note 1).

3.1.2. Time Course Gene Expression Analysis and Clustering Using Multiple Experiment Viewer

Time course gene expression analysis is a useful tool for understanding the role of TFs across time. By analyzing this type of data it is possible to discover new connections between TFs and the downstream pathways on which they act. Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) is a program available publicly at http://www.tm4.org/ (8, 9). Within this software package are a number of useful tools for the analysis of time course gene expression data.

Analysis of Variance

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is an extension of the student's t-test to more than two experimental conditions making it a good choice for analyzing a time course experiment. ANOVA identifies genes with significant differences in their mean expression across three or more time points by computing the F statistic (the ratio of the variance among replicates for a single time point in relation to the variance in mean across all the time points) and producing an output p-value. A gene expression change is considered signifi-cant if the p-value is lower than the user specified critical p-value.

ANOVA Input

MeV can take input from a variety of sources (.tav, Affymetrix, and .gpr), however the simplest method to input your gene expression data is to group your replicate experiments in Excel with a gene identifier column as your first column (like probe ID or gene symbol) and save it as a tab delimited text file. This file can then be opened in MeV by using the Load Data function (see Note 2). Along the top of the window, go to the Statistics button and select One-way ANOVA. The first step in running the ANOVA is selecting the number of experimental groups and then grouping your data (minimum of two replicate experiments per group) in the window. A critical p-value, which determines the cutoff for significance, is entered by default at p ≤ 0.01.

ANOVA Output

Once the ANOVA is run, the data is output into two lists: genes that met the significance cutoff and those that did not. It is now possible to perform additional analysis on these genes within the MeV software or to export the data from the Table View and work with it elsewhere.

K-Means Clustering

K-Means Clustering is a method by which a number of inputs (n), in our case genes, are grouped into a number (k) of clusters based on their similarity (nearest mean). This is a widely used algorithm to identify groups of genes that show similarity in expression over time. While there are exceptions, it is likely that genes that cohabit a cluster with a given TF are enriched for targets of this TF (5).

K-Means input

In order to perform clustering, the values of the time course gene expression data must first be normalized. The first step is to move the significant gene expression outputs from the ANOVA back into Excel and generate the average expression value of your replicates for each gene at each time point of your dataset. Next, this average data is log2 normalized using the Log(base) function in Excel. Generate the average expression value of the log normalized data for all time points for each gene, and the resulting number is subtracted from each log normalized time point. The resulting log- and mean-normalized data can then be saved in Tab Delimited Text format and loaded back into MeV for K-means clustering. Clustering in MeV has multiple options, however the most straightforward method is to select the Clustering button, then choose K-Means, then provide a number of potential clusters (the default is 10) (see Note 3), a number of iterations (the default is 50, preferably ∼500 to ensure the best ft for the data), and the distance metric (default is euclidean). This algorithm runs very quickly so it is possible to choose different starting conditions (e.g., cluster number) and view the results of each run independently.

K-Means Output

After performing the clustering, the resulting analysis includes the following: expression images, which provide heat maps of the clusters showing the expression levels of the genes that were grouped together, centroid graphs, which show the average expression value across your time course for each cluster, expression graphs, which show the individual expression values for each gene within a cluster, table views, which show the genes and their annotation data for each cluster, and cluster information, which shows the statistics for each cluster and what portion of the population they represent.

Time Course Gene Expression Correlated with Expression of a TF

Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient

This is a statistical method that can be applied to gene expression data as a measurement of the linear dependence between two genes (or arrays). Its use is based on the assumption that the expression values of a TF and the genes it regulates are similar (positive correlation) or complementary (negative correlation). Correlation coefficient values range from +1 to −1, where +1 suggests a strong correlation, 0 suggests no correlation, and −1 suggests negative correlation. As an example, the transcriptional coregulator LMO4 was suggested to regulate the expression of BMP7 based on correlation coefficients calculated from the expression values of the two genes in several microarray data sets (16).

For analysis of microarray data, correlation coefficients can be calculated to compare a single TF's expression with the rest of the genes from the time course data set:

Create an Excel spreadsheet with the log2 normalized expression values for each probe set that meets your present gene criteria, with each array replicate as an individual column and each probe set as an individual row (Make sure to use a gene identifier in the first column).

Create a new column for calculation of correlation coeffi-cients. To calculate each correlation coefficient use the “CORREL” function in Excel, with the log2 expression value of your transcription factor from each microarray as “Array1” (For example, if you have five replicates in your experiment, there will be five values selected for Array1) and the log2 expression value of your probe set of interest from each microarray as “Array2”.

Repeat this for each probe set in your spreadsheet, keeping the same values for your transcription factor in “Array1” and replacing the values for each “Array2” with those from each probe set (see Note 4).

Use two additional columns in your spreadsheet to calculate the t-test statistic for each correlation coefficient and the p-values for each t-test statistic (use TDIST function in Excel to calculate the p-value).

The list of probe sets can then be sorted by correlation coefficient and p-value. Plotting the distribution of correlation coef-ficients between the expression of a single TF and each probe set on the array should result in a normal distribution with a mean centered around zero and maximum and minimum values near +1 and −1, respectively. A cutoff value for relevant correlation coefficients can be selected (an ideal cutoff value is usually between 0.8 and 0.9), and a list of genes that lie above the cutoff value can be generated for downstream analysis as potential targets for your TF.

This process can also be executed with multiple TFs. Lists of transcriptional regulators in your microarray data set to be used in correlation analysis can be generated using probe sets with annotations such as Gene Ontology Biological Process “regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent” (GO ID 0006355) or Gene Ontology Cellular Component “nuclear” (GO ID 0005634). Calculate correlation coefficients for each transcription factor in the list compared to each gene on the array as described above if using only a small list of transcription factors. To perform a large-scale correlation analysis of multiple TFs, it is recommended to use numerical analysis software such as MATLAB (http://www.mathworks.com/) or R (http://www.r-project.org/) (see Note 5).

3.1.3. Transcription Factor Binding Site Analysis

We have used two programs to identify transcription factor binding site (TFBS) in candidate target genes. The first is BEARR (Batch extraction and analysis of cis-regulatory regions) (11) and the second is ConSite (10). Both these programs work on the premise that the TF consensus binding site is known (experimentally identified, for example by performing Casting experiments). As a negative control, this analysis is also performed on the genes that are not differentially expressed.

BEARR extracts defined sequences upstream and downstream of transcription start sites from several genes in a batch manner and gives a score to each site based on the provided transcription factor consensus binding sequence. However, as this program does not take into account the evolutionary conservation of sites or the region in which the site is, there are a high number of false positive results. Based on our experience, a site having a score over 6 is likely to be detected by EMSA. ConSite overcomes this problem by scoring sites based on across species conservation of the site and the region. The ConSite program has the ability to modify a search, making it stringent or lenient based on your requirements. We typically use 70–75% TFBS cutoff and 70–75% conservation cutoff. Limitations to using ConSite include the inability to extract sequences in batches and the requirement to manually paste the two sequences (usually human and mouse) being compared (see Note 6).

3.2. Competitive Electromobility Shift Assays

Electromobility shift assays (EMSA) are performed to demonstrate the actual binding of the transcription factor to the putative site. A γ32P-labeled probe (binding site) is incubated with or without an unlabelled perfect consensus sequence and the TF or protein lysate. The amount of unlabeled probe required to quench the signal is a measure of the binding affinity of the factor to the sequence.

3.2.1. Probe Preparation

The probe is designed to be ∼20–25 bp with the binding site at the center. Single stranded complementary oligonucleotides can be custom ordered for annealing. Dilute the primer stock (2 µg/µl) 1:10 (to a final concentration of 200 ng/µl). Use 250 ng of each oligonucleotide per annealing reaction. Set up the annealing reaction: 1.25 µl sense oligonucleotide, 1.25 µl antisense oligonucleotide, and 17.5 µl water to bring the reaction volume to 20 µl.

Heat at 80°C for 10 min in a heat block. Take the metal block of the heat block and leave it on the bench to slowly cool down at RT (overnight if necessary).

Kinase reaction: 20 µl of annealing reaction, 5 µl 10× Polynucleotide kinase (PNK) buffer, 2 µl γ32P ATP, 1 μl T4 PNK, and 22 μl water to bring it to a final volume of 50 μl (see Note 7).

Incubate at 37°C for 1 h (up to 2 h).

During this incubation time make a 10% native polyacrylamide gel using 1.5-mm spacers and a comb with thick wells to set up the gel (see Note 8).

Once the incubation is finished add 5 μl of loading dye to each kinase reaction and load on the gel. Use 1× TBE to run the gel.

Run the gel for ∼2 h at 350 V (the dye should reach the bottom of the gel just above the buffer).

Disassemble the gel by lifting the notched plate (this should be done behind a protective screen. Use a Geiger counter frequently to make sure there is no radioactive contamination elsewhere).

Cover the gel along with the plate on which it is placed with saran wrap and expose it for 30 s to a film. Develop the film. This film will then be aligned back to the gel and you can visualize the probe.

The film can be lined up with the gel to help cut out the band containing the annealed oligos. Cut it into small pieces and transfer them to a tube (the double-stranded annealed oligo moves slower than the single-stranded oligo).

Elute the probe by adding 400–500 μl of 50 mM NaCl in TE buffer. Incubate overnight at 4°C. For best results, the probe should be used within 5 days, since it will start decaying.

Measure the amount of probe to use for gel shift assay: Make 1:100 dilution of probe. Take 3 μl of each probe and spot it on a filter paper, allowing it to dry. Cut out the filter paper and place in the scintillation vial with 5 ml of scintillation fluid. Cap the vial and measure radioactivity in a scintillation counter. Calculate the amount necessary for each reaction. You will need ∼200 counts per second (cps) of labeled probe per gel shift reaction.

3.2.2. Gel Shift Reaction

Prepare a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (or can be commercially bought). It takes over an hour to polymerize. Use 1-mm spacers and a comb with 12 wells and plates to set up the gel (see Note 9).

To set up the reaction add the following, mix gently and incubate on ice for 10–20 min (allow 30 s to 1 min interval between samples). Gel shift reaction: 4 μl 5× Gel shift buffer, 4 μl 10 mg/ml BSA, 1 μl 100 mM DTT, 1 μl poly dIdC (1 μg/μl) (optional),×μl, Competitive oligo (Unlabelled consensus sequence) (Use 1–100 molar excess), (10–500 ng)μl DNA binding protein,×μl 200cps probe, and bring the reaction volume to 20 μl with water.

Load the samples to the gel without a dye in the same sequence as you set them up. Make sure to run a probe only lane as a negative control with 20 μl loading dye. Run the gel for 2.5 h at 250 V (or till the dye reaches the top of the bottom buffer container). Once the gel is done place the Whatman paper on the gel and remove from the plate. Dry it for ∼20–30 min in a gel dryer and expose it to a film. If the signal is weak, the cassette with the film and the gel can be placed in −80°C freezer to develop overnight.

To compute relative affinity increasing amounts of cold consensus probe (competitor) is added to the gel shift reaction while keeping the protein or nuclear extract and the radiolabeled probe as constant. The DNA–protein complexes are quantified by cutting out the Whatman paper with the dried gel and measuring the counts using a scintillation counter (the exposed film can be lined up with the Whatman paper to ensure you are cutting the right bands). The percent binding of the TF to the labeled probe in presence of a competitor relative to that in its absence is used to make a competitive binding curve. This binding curve can then be used to estimate the concentration of unlabeled oligo (IC50) needed for 50% of inhibition of binding. The relative affinity can be calculated by dividing the IC50 of a test gene or TFBS to the IC50 of a known gene or TFBS (17).

3.3. Chromatin Immuno--precipitation Assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays can be performed on either undifferentiated or differentiated primary human keratinocytes (Invitrogen) depending on when the TF being tested is expressed. If using undifferentiated keratinocytes, cells should be in the growth phase. The number of cells required per ChIP is to some extent dependent on how good the antibody is. In most cases, 1 × 107 should be enough; however, the number of cells can be reduced to 2 × 106 per ChIP (or 1.5 10 cm plate per ChIP for undifferentiated cells and 1 plate per ChIP for differentiated cells).

3.3.1. Staph A Cell Preparation

Wash Staph A Cell: (1) Add 10 ml of 1× Dialysis Buffer (DB) to resuspend 1 g of lyophilized Staph A cells (You can use a P1000 Pipetman or allow 30′ to rehydrate, which helps resuspension); (2) Transfer the resuspended cells to a 15-ml tube and centrifuge at 2,300 × g for 10′ at 4°C, pour off supernatant; (3) Wash the pellet again with 1× DB, spin and pour off supernatant; (4) Resuspend in 3 ml of PBS, 3% SDS, 10% BME (To 2.25 ml of 1× PBS, add 450 μl of 20% SDS and 300 μl of beta-mercaptoethanol) (5) Boil for 30′ in fume hood and pellet the cells down at 2,300 × g for 10′ at RT, pour off supernatant into chemical waste; (6) Wash with 10 ml of 1× DB and pellet cells down at 2,300 × g for 10′ at RT, pour off supernatant (7) Repeat step 6 and resuspend in 4 ml of 1× DB (8) Make 100-μl aliquots in 0.5-ml tubes, snap-freeze and store at −80°C for indefinite time.

Blocking Staph A Cells: The Staph A cells must be blocked before they can be used for ChIP assays. Once blocked they can be stored at 4°C for up to 14 days. (1) Thaw one tube (100 μL each) of Staph A Cells for four IPs. (2) Add 10 μl of each of 10 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA and 10 mg/ml of BSA, mix by pipette. (3) Incubate overnight on a rotating platform at 4°C (You can incubate them on a rotating platform for 2 h at RT or ≥3 h at 4°C if necessary) (4) The next day, the Staph A cells are transferred to a 1.5 ml tube and spun at 20,000 × g for 3′ at 4°C and supernatant discarded. (5) The pellet is resuspended in 1 ml 1× DB, centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3′ at 4°C, and supernatant discarded (6) Repeat step 5 (7) Resuspend the pellet in 100 μL of 1× DB with 1 mM PMSF (use 1 μl of 100 mM PMSF).

3.3.2. Day 1: Preparation of Cross-Linked Cells

To fix cells, add formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% directly to the media in plates and rock gently for 10 min at RT.

The cross-linking reaction is stopped by adding 2.5 M Glycine at a final concentration of 0.125 M for 5 min.

Wash cells with cold 1× PBS at least twice. Keep plates on ice while washing. After the last wash, leave about 1 ml of PBS in the plate.

Scrape cells from the plates and transfer the PBS with the cells into a 50-ml tube. You can scrape enough cells for four to six ChIPs in one 50-ml tube.

Spin the tube at 590 × g for 10′. Carefully remove PBS and wash the cells again with 40 ml PBS. Pellet again and aspirate out the supernatant.

You can proceed to sonication step immediately or freeze the cells at −80°C for later use.

3.3.3. Day 2: Sonication, Preclear, and Antibody Incubation

The cell pellet is resuspended in SDS lysis buffer (Add fresh protease inhibitors: 1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mg/ml Aprotinin and Leupeptin). We use 400 μl lysis buffer per ChIP and sonication is performed (see Note 10).

Take out 30 μl of sonicated material to do a sonication check before you proceed with the ChIP. Bring it up to 50 μl with water. Add 2 μl of 5 M NaCl and place the tube in boiling water for 15′. Perform a PCR-purification using Sigma PCR-purification kit. Elute in 30 μl water and run on a 2% gel. It is best to get majority of the chromatin to an average of ∼500 bp.

The samples are then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10′ at 4°C and supernatant transferred to a new tube. All the sonicated material can be combined and realiquoted into 400 μl per tube. This is done to ensure that sonicated chromatin for all ChIPs is the same (the sonicated chromatin can be frozen at this stage).

Preclear chromatin by adding 10 μl of blocked/washed Staph A cells (freshly added 1 μl of 100 mM PMSF to 100 μl of blocked Staph A cells) per 1 × 107 cells (Staph A cells are used in place of Protein A agarose beads, as they reduce nonspecific binding, are easier to work with and fairly inexpensive). Incubate on rotating platform for no longer than 15′ at 4°C. Save the remaining Staph A cells for the next day at 4°C.

Microfuge at 20,000 × g for 5′ at 4°C. Transfer supernatants from all samples to a new tube, measure volume and divide equally into new 1.5-ml eppendorf tubes (can use 2 ml tubes, if you have higher volume).

Make twice the volume of ChIP dilution buffer (800 μl of buffer for 400 μl of sonicated chromatin). Add fresh protease inhibitors to the same final concentration as step 1.

Add 1–10 μg of antibody (see Note 11) to each sample. Incubate on a rotating platform at 4°C overnight. We use IgG as a negative control, RNA polymerase II as a positive control and one or two different concentration of your test antibody.

3.3.4. Day 3: Washing and Reverse Cross-Linking

To the sample add 12.5 μl of Staph A cells (add fresh 1 μl of 100 mM PMSF per 100 μl of blocked and washed Staph A cells). Incubate on rotating platform for 15′ at RT.

Microfuge samples at 20,000 × g for 4′ at 4°C. Save all the supernatant from IgG IP for “Input”; it will be later used at the reverse cross-linking step. Pour off the supernatant of the other samples (see Note 12).

Wash pellets with milliliters of Low-Salt buffer, invert tubes 20–30 times by hand at RT, spin down at 11,000 × g for 4′ and pour off the supernatant.

Repeat step 3 and then wash twice with High-Salt buffer, once with LiCl and twice with TE in a similar manner (see Note 13). Remove final TE wash buffer by aspirating.

Prepare fresh elution buffer (1% SDS, 5 mM NaHCO3) at room temperature (do not put on ice). You will need 100 μl of elution buffer per IP.

Add 50 μl of elution buffer to each tube and shake on vortexer for 15′ at RT.

Pellet down the cells at 20,000 × g for 3′ at RT. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Repeat steps 6 and 7 combining the supernatant.

Microfuge the combined supernatant again at 20,000 × g for 5′ to remove any traces of staph A cells. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

Add 4 μl of 5 M NaCl (0.2 M NaCl final concentration) to each IP. For “10% Input” transfer 10% volume of the “Input” saved from step 2 to a new tube. Bring the volume to 100 μl and add 4 μl of 5 M NaCl. If the volume of the 10% Input is higher than 100 μl, increase the NaCl accordingly.

Reverse cross-link all samples and the “10% Input” by placing them at 65°C for 4 h or overnight. The samples can be frozen at −20°C after this stage if necessary, but should not be left for more than a day or two.

3.3.5. Day 4: Colum Purification and PCR Analysis

Each sample is column purified using Sigma PCR cleanup kit (Can also use Invitrogen Purelink PCR micro kit, if you want to elute in a much smaller volume – down to 10 μl). Elute in 30–50 μl of water.

It is crucial to have primers with good primer efficiency for PCR. Before using your primers for ChIP, do a PCR with dilutions of your input alone (1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000) to check for primer efficiency. The primers have a good efficiency if band intensity is relative to the dilution of the input sample. Also, it is important to determine what annealing temperature works best for each primer. It is much easier if primers that are being used have the same annealing temperature.

Setup PCR in a 20 μl reaction volume: 2 μl of 10× buffer, 1 μl of 2.5 mM dNTP, 0.5 μl of each forward and reverse 10 μM primers, 0.5–1 μl Taq Polymerase (We use one from Denville, but it can be substituted with Taq from other companies) (see Note 14).

Controls are very important in a ChIP experiment. For IP, IgG serves as a negative control and RNAPolII as a positive control. For PCR, the positive control primer will be against a region where RNAPolII is sure to bind like the RNAPolII promoter region. This same primer however will give no band with IgG IP. Presence of PCR product in IgG IP indicates nonspecific binding. A negative control primer is designed in a region away from the promoter region that should have no RNAPolII binding. We use primer in the DHFR 3′ UTR region. Negative control primer can also be designed in a region far away from the TF binding site.

3.4. Luciferase Reporter Assays

To test if the validated TF binding site is functional, reporter assays are performed. HaCaT cells are easily transfectable and are therefore ideal for this assay, but primary mouse and human keratinocytes can be used as well. In some cases it is most useful to use a nonkeratinocyte cell line that does not express the TF in question. The cells are transfected with reporter plasmid expressing the luciferase gene downstream of a promoter containing the relevant TF binding site. The TF expression plasmid is cotransfected with the reporter plasmid, cells are collected and luciferase activity measured. A mutation is also made in the TF binding site and this reporter plasmid is used as a negative control. In addition to transfecting the pGL3 Firefly-luciferase reporter plasmid, Renilla luciferase plasmid is cotransfected for normalization purpose. Below is the experimental design with all the controls (Table 1) (see Note 15).

Table 1. Experimental design of reporter assay.

| Sr. | Plasmids to be transfected | Amount of plasmid per well |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | pGL3 reporter-Empty + Empty expression plasmid + Renilla plasmid | 1.6 μg |

| 2 | pGL3 reporter-Promoter + Empty expression plasmid + Renilla plasmid | 1.6 μg |

| 3 | pGL3 reporter-Promoter + TF Expression plasmida + Renilla plasmid | 1.6 μg |

| 4 | pGL3 reporter-Promoter-mutb + TF Expression plasmid + Renilla plasmid | 1.6 μg |

| 5 | pGL3 reporter-Promoter-mut + Empty expression plasmid + Renilla plasmid | 1.6 μg |

Titration of the expression plasmid is important to determine the best concentration

The TFBS in the promoter region is mutated using site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). If the site being tested is functional, this mutation will result in abolishing or significantly reducing the luciferase activity

3.4.1. Plating and Transfection

A day prior to trasfection plate HaCaT cells grown in low calcium medium (undifferentiated state) at 1 × 105 cells per well in a 12-well plate. This will give a confluency of 80–90%, which is ideal for transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

The following day take polypropylene tubes (1.5 ml eppendorf or 15 ml conical tube depending on the volume) and prepare the DNA-lipofectamine mix.

For all transfections make a master mix since each transfection is done in triplicate. Calculation must be done for 3.5 wells.

To the first tube add plasmid DNA to 100 μl of optiMEM. Make master mix for 3.5 wells.

To the second tube add 4 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 to 100 μl of optiMEM. Flick the tube or mix gently and let it sit. Again to prepare master mix for 3.5 wells you will add 14 μl Lipofectamine to 350 μl optiMEM. Let it sit for 5′.

Add the DNA-optiMEM mix to the lipofectamine-optiMEM. Let it sit for 20′ in the hood.

While waiting for the incubation to complete, aspirate the media from the cells and replace it with fresh low calcium media.

After 20′ add the DNA-Lipofectamine complex to each well. To mix, rock the plate back and forth a couple of times and place it back in the 37°C incubator.

Change media 12–16 h after transfection. Collect cells for luciferase assay after 48 h.

3.4.2. Luciferase and Renilla Activity Measurement

Luciferase activity is measured by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) where two reporter assays are performed sequentially from the same sample, one from Firefly luciferase and the second from the Renilla luciferase. The latter is used to normalize for the number of cells that are actually being transfected.

Cells are collected for luciferase activity measurement 48 h after transfection. Aspirate the media from the cells and add 200 μl of 1× passive lysis buffer (Materials). Freeze the plate with the lysis buffer in −80°C for at least an hour. Freeze thawing helps lyse the cells. Take out the plate and thaw at RT. During this time also start thawing the LARII reagent and the Stop & Glo reagent.

Scrape cells from each well and place in a 1.5 ml eppendorf tube. Vortex for 10 s and spin down for 10′ at 20,000 × g at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube (see Note 16).

To a luminometer tube add 50 μl of LARII. Add 5 μl of the transfected HaCaT cell lysate. Mix and measure firefly luciferase activity. To the same tube add 50 μl of Stop & Glo reagent and measure Renilla luciferase activity. Background activity is measured by adding the LARII and Stop & Glo in the same order without the lysate.

For analysis, first subtract the background reading from all readings, then, divide the Renilla luciferase measurement from the Firefly luciferase measurement, thus normalizing to the number of cells that are being transfected. These Firefly luciferase measurements are then graphed normalized to cells transfected with empty plasmids. Include standard error measurements based on the triplicate wells readings of each transfection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by TRDRP dissertation award 17DT-0192 (to A.B.), NIH-NLM Biomedical Informatics Training grant 5T15LM007743 (to MS) and NIH grant AR44882 (to BA). The authors acknowledge the contributions of other laboratory members to the approaches described in this chapter. We thank Amy Soto and Suman Verma for reading the manuscript. We acknowledge the Expression Analysis Core at UC Davis for ChIP training.

Footnotes

You can use a certain fold value as a cutoff to make a list more manageable. We use a fold cutoff of 1.5–2.0 depending on the datasets.

The array type and species can be selected when loading your data into MeV if present within the software providing you with gene annotation data. If your array information is not present in the software you can also manually load the annotation data that is provided with your array platform.

Since it is possible to run numerous K-means cluster analyses quickly, it is helpful to choose a variety of possible clusters and compare the results between the different runs to look for repeated and unique patterns. The number of clusters you decide upon will depend directly on your data.

In the case where a single TF is represented with multiple probe sets on an array, one probe set can be randomly selected for comparison to all genes, while the other can be included with the list of all the other probe sets on the array. This allows for a nice positive control, where one would expect the correlation value between the two probe sets of the same TF to be close to 1.

The Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient can also be used for global gene expression analysis of multiple arrays. For example, it can be used to compare the global similarity in gene expression between two tissue types at a specific time or stage in development. In this case the correlation coef-ficients are calculated across all probe sets for each pair of sample types, and then averaged to create a single correlation coefficient between the pair of tissues. Another useful application for correlation is to compare the expression level of a transcriptional regulator of interest to a potential target gene of interest across many arrays. From each array plot the log2 expression value of the transcriptional regulator versus the log2 expression level of the target gene of interest, and from the plot that was generated calculate the Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient. Again, correlation coefficients closer to 1 have a high correlation and those closer to 0 have a low correlation.

In case the TF of interest is not in the pull down list, you can upload the Position Weight Matrix or Raw counts matrix of your TF using the “User defined profile”. It is important to note here that the example given to the right of the sequence of ACTG is incorrect. It is ACGT instead.

To label the probe γ32P ATP is used, which is a high energy isotope with a short half life of 14 days. It is at the labeling step that maximum care should be taken, keeping the tube with radioactive 32P in acrylic case and using an acrylic shield for protection. Both the labeling reaction and running the gel should be done behind acrylic shields, especially when preparing the probe. Be extremely careful while working with radioactive 32P using a Geiger counter constantly to avoid contaminating any part of your clothing and other areas in the lab. Follow all rules specified by your university or institution.

It is important to use the long vertical gel apparatus at this step, so that there is enough separation in case annealing is incomplete and you can cleanly excise the gel band with the annealed probe.

Commercially available gels (Invitrogen-Native PAGE Novex 4–16% Bis–Tris gels; Cat. No.BN1002BOX) can be used at this stage to get cleaner results.

Optimizing sonication is important for a successful ChIP experiment, and to get consistent results. It is best to do this with the exact number of cells with which you want to do the ChIP. Using the Bioruptor, 1 × 107 keratinocytes in 800 μl lysis buffer (enough for two ChIPs, with a good antibody) are sonicated to average 500 bp by setting it on High and sonicating 15 s on and 15 s off for 30′.

The amount of antibody required for ChIP varies widely and should be tested empirically. Make sure to run the positive and negative controls to ensure that there is no nonspecific binding.

Supernatant of the IgG IP is used as input, since that is the total amount of DNA that you are starting out with and there should be no DNA binding to IgG in a specific manner.

The LiCl wash buffer has the highest amount of salt and hence is the most stringent. Washing once with this buffer is usually enough. However, if you are getting nonspecific binding with IgG, wash the Staph A cells twice with LiCl buffer.

You can also perform quantitative RT-PCR and calculate quantitative levels of enrichment in antibody ChIP as compared to IgG as a percentage of input.

As a positive control, you can use pGL3-promoter vector (Promega; Cat. No. E1761).

The lysates can be stored at −20°C for a couple of days, although the luciferase activity may reduce slightly.

References

- 1.Nickoloff BJ. Keratinocytes regain momentum as instigators of cutaneous inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:207–17. doi: 10.1038/nrm2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koster MI, Roop DR. Mechanisms regulating epithelial stratification. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long AD, Mangalam HJ, Chan BY, Tolleri L, Hatfield GW, Baldi P. Improved statistical inference from DNA microarray data using analysis of variance and a Bayesian statistical framework. Analysis of global gene expression in Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19937–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Z, Mannik J, Soto A, Lin KK, Andersen B. The epidermal differentiation-associated Grainyhead gene Get1/Grhl3 also regulates urothelial differentiation. Embo J. 2009;28:1890–903. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin KK, Chudova D, Hatfield GW, Smyth P, Andersen B. Identification of hair cycle-associated genes from time-course gene expression profile data by using replicate variance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin KK, Kumar V, Geyfman M, Chudova D, Ihler AT, Smyth P, Paus R, Takahashi JS, Andersen B. Circadian clock genes contribute to the regulation of hair follicle cycling. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeed AI, Bhagabati NK, Braisted JC, Liang W, Sharov V, Howe EA, Li J, Thiagarajan M, White JA, Quackenbush J. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:134–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, Sturn A, Snuffin M, Rezantsev A, Popov D, Ryltsov A, Kostukovich E, Borisovsky I, Liu Z, Vinsavich A, Trush V, Quackenbush J. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–8. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelin A, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. ConSite: web-based prediction of regulatory elements using cross-species comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W249–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vega VB, Bangarusamy DK, Miller LD, Liu ET, Lin CY. BEARR: Batch Extraction and Analysis of cis-Regulatory Regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W257–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi X, Zhang SX, Yu W, DeMayo FJ, Rosenberg SM, Schwartz RJ. Expression of Nkx2-5-GFP bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice closely resembles endogenous Nkx2-5 gene activity. Genesis. 2003;35:220–6. doi: 10.1002/gene.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker T, Pasca di Magliano M, McManus S, Sun Q, Bonifer C, Tagoh H, Busslinger M. Stepwise activation of enhancer and promoter regions of the B cell commitment gene Pax5 in early lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2009;30:508–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells J, Dai X. Using siRNA knockdown in HaCaT cells to study transcriptional control of epidermal proliferation potential. Methods Mol Biol. 585:107–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-380-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe SE, Boutros M, Michelson AM, Church GM, Halfon MS. Preferred analysis methods for Affymetrix GeneChips revealed by a wholly defined control dataset. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R16. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-r16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang N, Lin KK, Lu Z, Lam KS, Newton R, Xu X, Yu Z, Gill GN, Andersen B. The LIM-only factor LMO4 regulates expression of the BMP7 gene through an HDAC2-dependent mechanism, and controls cell proliferation and apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:6431–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Z, Lin KK, Bhandari A, Spencer JA, Xu X, Wang N, Lu Z, Gill GN, Roop DR, Wertz P, Andersen B. The Grainyhead-like epithelial transactivator Get-1/Grhl3 regulates epidermal terminal differentiation and interacts functionally with LMO4. Dev Biol. 2006;299:122–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]