Abstract

A 57-year-old woman presented with adhesional small bowel obstruction and required a laparotomy and adhesiolysis. The postoperative period was complicated by pulmonary embolism. In addition, computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram also demonstrated several indeterminate pleural based pulmonary nodules suspicious of a primary malignancy. Review of this patient’s past medical history revealed a road traffic collision 29 years previously which required a laparotomy, left nephrectomy, splenectomy, and repair of the left hemi-diaphragm. Radiological surveillance with follow-up chest CT demonstrated stable appearance of the indeterminate nodules, and a diagnosis of thoracic splenosis was considered the most likely explanation of the imaging findings. Thoracic splenosis must be considered in patients presenting with lung nodules and a past history of thoracoabdominal trauma. Radionuclide studies with technetium99m (Tc99m) sulfur colloid or Tc99m heat damaged red cell scans can help confirm or refute this diagnosis and thereby reassure both patient and clinician.

Background

Thoracic splenosis is a rare condition where ectopic splenic tissue is autotransplanted into the thoracic cavity, usually as a consequence of previous splenic rupture. We wish to highlight a case of thoracic splenosis diagnosed 29 years after thoracoabdominal trauma where an initial diagnosis of a primary lung malignancy based on imaging was subsequently dismissed. The aim of presenting this case report is twofold. Firstly, we wish to highlight this condition when confronted with an indeterminate lung nodule on a background of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture and splenic injury. Unnecessary and invasive investigations can therefore be avoided and patients can be appropriately reassured. Secondly, we wish to emphasise that a thorough and complete clinical history continues to remain essential in clinical practice, with diagnostic imaging being a complementary but nevertheless useful tool.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old woman presented as an emergency with small bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions. She underwent a laparotomy and adhesiolysis. Twenty-nine years earlier, she had been involved in a road traffic collision and underwent a splenectomy, left nephrectomy, and diaphragmatic repair. The patient was a heavy smoker with a 40-pack year history.

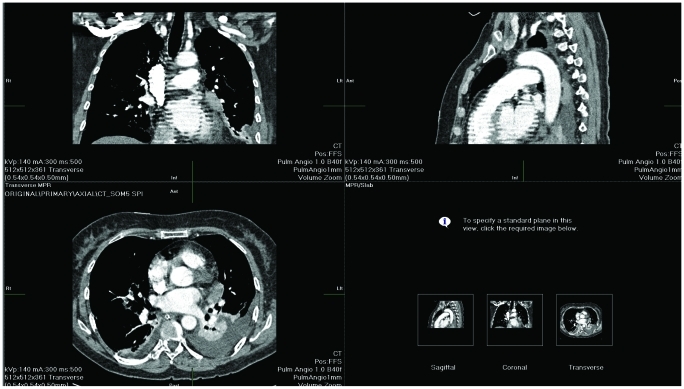

Postoperatively, she developed a chest infection and pulmonary embolism was diagnosed on computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA). An incidental note was made of several pleural based nodules adjacent to the mediastinum (figs 1 and 2). This finding was reported as being suspicious for either a primary bronchogenic carcinoma or metastatic disease.

Figure 1.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax demonstrating an 18 mm left pleural nodule unchanged from a previous CT performed 1 month earlier (fig 2).

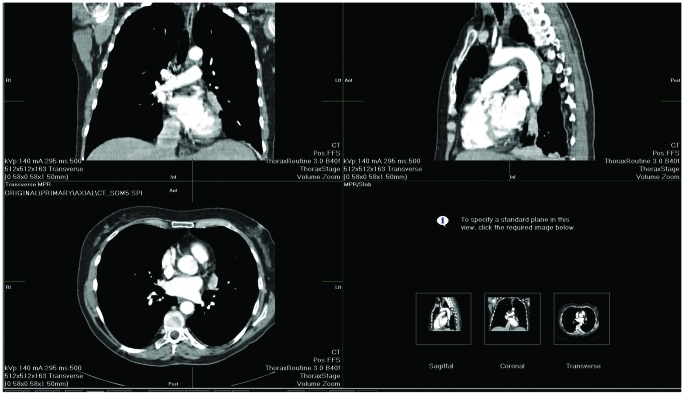

Figure 2.

See fig 1 caption.

Follow-up with a respiratory physician and a staging CT of the chest and abdomen was performed. The examinations were reviewed by a second radiologist who reported no enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes and felt that the previously reported changes were not typical of a bronchogenic carcinoma.

On careful review of the CT scans at the respiratory multidisciplinary meeting, a diagnosis of thoracic splenosis was suggested as the most likely diagnosis. Future management involved follow-up by the respiratory physicians with serial chest radiographs for further reassurance, and the patient was discharged to the general practitioner’s care.

Discussion

Thoracic splenosis is described as autotransplantation of splenic tissue to abnormal locations in the thoracic cavity following splenic injury.

Von Kuttner was the first to introduce the concept of splenosis in 1910.1 Shaw and Shafi later described a case of post-traumatic thoracic splenosis at postmortem examination in a 20-year-old man who died of overwhelming sepsis.2 A Medline search found 54 cases in the English literature. In the majority of cases, the patient had a history of abdominal and thoracic trauma and the findings were incidental. All cases were diagnosed between 1 and 42 years later, with an average of 18.8 years.3–5

Splenic tissue proliferates on the serous surface of the pleural cavity and appears as nodules within the pleural surfaces, interlobular fissures or lung parenchyma.6 The pleural nodules of ectopic splenic tissue are normally smaller than 3 cm, although masses as large as 8.5 cm have been reported.5 Splenosis post-splenic rupture is becoming more common and is now thought to occur in up to 67% of patients with splenic rupture.7 Normand et al found that abdominal splenosis is more common than thoracic splenosis, occurring in only 18% of patients.8

In this case the pleural masses were initially thought to represent either a primary bronchogenic carcinoma or metastatic disease. It is not uncommon to discover pleural based metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma.9 However, when there is a history of thoracoabdominal trauma, thoracic splenosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis along with pleural metastases, lymphoma, asbestos related pleural plaques, mesothelioma and thymoma.10 Investigations to diagnose thoracic splenosis include indium labelled platelets or Tc99m heat damaged erythrocytes, which are sequestered and phagocytosed by the spleen.11 Fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core biopsy techniques also have been used to establish the diagnosis; however, FNA cytology has the disadvantage of resembling lymphoproliferative disorders,12 and thus may be misleading.

Learning points

Clinicians require a high index of suspicion for thoracic splenosis in a patient presenting with a left pleural based mass and a history of thoracoabdominal trauma.

Symptoms of thoracic splenosis include pleurisy and haemoptysis, although, more commonly, the patient is asymptomatic with the abnormality being found incidentally on CT

Splenic remnants do not require surgical removal. In fact, they can continue to function immunologically, and provide some defence against encapsulated organisms.13

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication

REFERENCES

- 1.Von Kuttner H: Diskussion: Mizentirpation und ruentgenbehandlung bei leukamie. Berl Klin Wochenschr 1910; 47: 1520 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw AFB. A traumatic autoplastic transplantation of splenic tissue in man with observation of late results of splenectomy in six cases. J Pathol 1937; 45: 215–35 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madjar S, Weissberg D. Thoracic splenosis. Thorax 1994; 49: 1020–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsunezuka Y, Sato H. Case report: Thoracic splenosis; from a thoracoscopic point of view. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998; 13: 104–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.VM, Morgan ME. Thoracic splenosis. Clin Nucl Med 1994; 49: 115–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarda R, Sproat I, Kurtycz DF, et al. Pulmonary parenchymal splenosis. Diagn Cytopathol 2001; 24: 352–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang AH, Shafter K. Thoracic splenosis. Radiology 2006; 239: 293–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Normand JP, Ioux M, Dumont M, et al. Thoracic splenosis after blunt trauma: frequency and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 161: 739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sealy WC. Carcinoma of the lung. Sabiston textbook of surgery. London: WB Saunders; 1971: 1847–57 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wold PB, Farrell MA. Pleural nodularity in a patient with PUO. Chest 2002; 122: 718–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yammine JN, Yatim A, Barbari A. Radionuclide imaging in thoracic splenosis and a review of literature. Clin Nucl Med 2003; 28: 121–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renne G, Coci A, Biraghi T, et al. Fine needle aspiration of thoracic splenosis. A case report. Acta Cytol 1999; 43: 492–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hathaway JM, Harley RA, Self S, et al. Immunological function in post- traumatic splenosis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1995; 74: 143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]