Abstract

Articular cartilage (AC), situated in diarthrodial joints at the end of the long bones, is composed of a single cell type (chondrocytes) embedded in dense extracellular matrix comprised of collagens and proteoglycans. AC is avascular and alymphatic and is not innervated. At first glance, such a seemingly simple tissue appears to be an easy target for the rapidly developing field of tissue engineering. However, cartilage engineering has proven to be very challenging. We focus on time-dependent processes associated with the development of native cartilage starting from stem cells, and the modalities for utilizing these processes for tissue engineering of articular cartilage.

Keywords: cartilage tissue engineering, mesenchymal stem cells, embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells

1. Introduction

The high incidence of cartilage damage and disease has prompted considerable research into the development of cartilage replacement substitutes. Initially, the cells of choice for cartilage tissue engineering were autologous chondrocytes, periosteocytes and perichondrocytes (1–4). These cells can be isolated from the less weight-bearing areas of the joint, amplified in vitro, and seeded into a scaffold to form cartilage that can be implanted back into the joint without compromising the patient’s immune system. However, there are several obstacles to such a scenario. Adult chondrocytes undergo dedifferentiation into fibroblast-like cells when grown in monolayer cultures (5, 6), exert slow rates of in vitro propagation (7), and gradually lose their ability to produce cartilaginous matrix (8). Attempts to induce re-differentiation of cultured chondrocytes include culture in 3D settings and delivery of chondrogenic genes (9, 10). The use of stem cells, which can potentially differentiate into chondrocytes under appropriate conditions, is now explored as a promising alternative. However, under currently used differentiation protocols, stem cells are unable to fully differentiate into functional mature chondrocytes (11), leading to the formation of cartilaginous tissue with subnormal biochemical and mechanical properties (12). We discuss the strategies associated with directing stem cells to form functional cartilage tissue in vitro and in vivo with special focus on the time-dependent aspects of this process.

The field of cartilage tissue engineering initially - and somewhat prematurely - focused on developing biological substitutes to replace articular cartilage (AC), instead of basic research towards more fundamental understanding of the processes that occur in the development of normal AC (13). More recently, the field of tissue engineering has shifted toward a new concept of “in vitro biomimetics of in vivo tissue development “ (14, 15). The newly emerging methodology for utilizing the concepts of developmental biology as a basis for designing tissue engineering systems has also been called “developmental engineering” to emphasize that it is not the tissue but the process of in vitro tissue development that has to be engineered (15). Understanding the temporal changes in the levels of transcription and growth factors and in the cell morphology and extracellular matrix (ECM) composition would lead to more controlled strategies to direct the engineering of functional AC from stem cells.

2. Stages in the development of native cartilage

Growing cartilage is found in two locations at each end of a developing long bone: the growth plate and the articular–epiphyseal growth cartilage (16). First, we describe the chondrogenic component of endochondral ossification in developing bones (17). Then, we focus on the articular–epiphyseal cartilage which forms AC within the synovial joints.

2.1. Chondrogenesis in endochondral ossification

Stage I – Precartilage Condensation

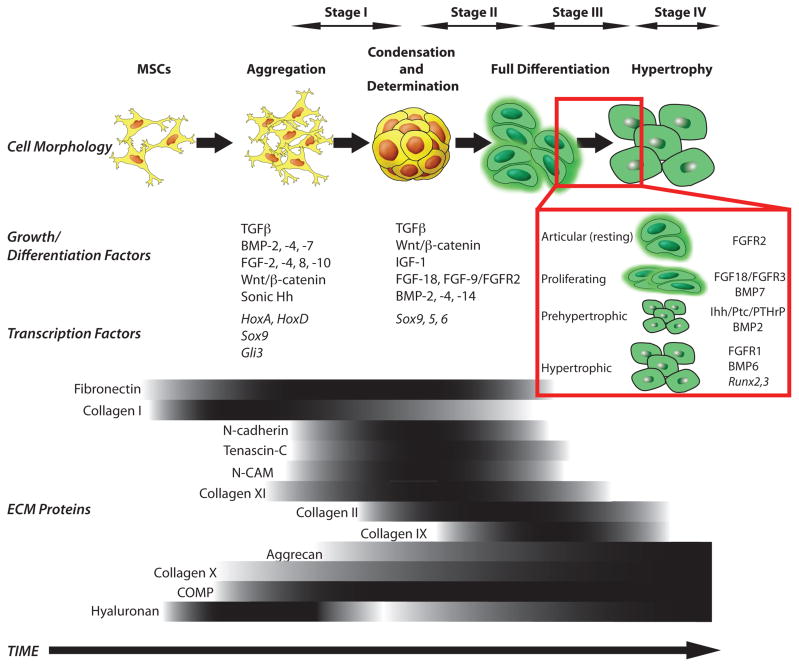

Native AC and long bones are formed by endochondral ossification (18). This process begins from the lateral growth plate (19) containing skeletogenic mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that secrete an extracellular matrix (ECM) rich in hyaluronan and collagen type I (20) (Figure 1). MSCs move toward the center of the limb (21) and begin to aggregate, causing an increase in cell packing density (20). At that stage, MSCs stop proliferating and expressing collagen I, and begin expressing N-cadherin, tenascin-C, neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) and other adhesion molecules that allow them to aggregate (21). Formation of tight aggregates marks the start of the process called precartilage condensation that entails aggregation of MSCs and an increase in hyaluronidase activity. The resulting decrease in hyaluronan in the ECM decreases cell movement and allows for close cell-cell interactions (22).

Figure 1. Sequence of events during native chondrogenesis.

The different stages are represented schematically, showing the temporal patterns of growth, differentiation and transcription factors as well as changes in cell morphology. The extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that distinguish the different stages are indicated below by the gradients of expression. Darker zones in the gradients correlate to higher levels of expression.

This establishment of cell-cell interactions is likely involved in triggering signal transduction pathways that initiate chondrogenic differentiation, such as homeobox (Hox) transcription factors encoded by the HoxA and HoxD gene clusters (21).

Mesenchymal condensation is also affected by small proteoglycans such as versican and perlecan. Versican enhances mesenchymal condensation (24), and can bind to molecules present in the ECM of precartilage micromass (24). Similarly, perlecan is present in the very early stages of chondrogenesis (day 12.5 of gestation) during mouse embryo development, and is capable of inducing cell aggregation, condensation, and chondrogenic differentiation in vitro (25). Perlecan binds to other ECM molecules, as well as to the growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (26). FGF-9 is expressed within condensing mesenchyme early in development (27). BMP-2, -4, and -7 coordinate in regulating the patterning of limb elements within the condensations depending upon the temporal and spatial expression of BMP receptors and antagonists, such as noggin and chordin (28). Other extracellular adaptor proteins detected in the early stages of chondrogenesis are matrilins, which support matrix assembly. In mouse, matrilin-1 and -3 are expressed in restricted temporal and spatial patterns (29, 30).

An interesting computational modeling study emphasized the role of temporal control in condensation during chondrogenesis (31). The formation of spatial “spot-stripe” patterns detected during precartilage condensation was sensitive to the period of time that cells were exposed to generic activator morphogen and to the threshold level for cell differentiation. If the exposure time was too short, small condensations were produced. If the exposure was too long, irregularly shaped condensations were formed. Although the stable activator peaks were generated during the condensation process, those peaks tended to wander in space and time.

Mesenchymal cell condensation, or precartilage condensation, is regarded as the major event of the MSC commitment to the chondrogenic lineage, after which tissue-specific transcription factors and structural proteins begin to accumulate (32). In vitro studies have indicated that transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and Wnt/β-catenin signaling govern this process (33). It is speculated that TGFβ acts via stimulation of fibronectin synthesis (34) that is necessary for stabilization of mesenchymal-endothelial junctions (35). Furthermore, in vivo studies have confirmed that Sox9 is the first transcription factor that is essential for chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage formation (36, 37) (Figure 1).

Stage II – Determination and Early Differentiation

The next step in the process of chondrogenesis is MSC determination to the chondroprogenitor stage (Figure 1). Cells at the center of precartilaginous condensation stop expressing adhesion molecules, resume proliferation and initiate production of ECM (21), undergoing early chondrogenic differentiation. The regions of determination and early differentiation spread rapidly from the center of the micromass to the periphery, while the peripheral MSCs form perichondrium. The perichondral cells express patterning factors and also give rise to new chondrocytes (21). Expression of FGF-2, FGF-5, FGF-6 and FGF-7 has been observed in this perichondral mesenchyme surrounding the condensation (38). FGF-18 has been shown to regulate early chondrocyte differentiation but is also detected at later stages regulating hypertrophy (39). Tight spatiotemporal coordination of these actions is controlled by the interplay of various factors, such as the Sox genes trio (Sox 9, 5, 6), sonic hedgehog (Shh), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), FGFs and TGFβ signaling (40) (Figure 1).

The Sox trio, comprised of high-mobility-group (HMG) domain transcription factor Sox9 and accessory transcription factors Sox5 and Sox6, controls early chondrogenic differentiation (41, 42). The Sox trio also maintains the chondrocyte phenotype at later stages and directly regulates expression of ECM molecules, such as collagen (mainly types II, IX, X, XI) and proteoglycans (aggrecan, decorin, annexin II, V and VI). Sox genes and BMP signaling are tightly coupled functionally (43). It has also been suggested that Shh and FGF participate in cooperative activation of Sox9 expression (44). Shh signaling is mediated by the Shh receptor Patched (Ptc1), which activates another transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo) and inhibits processing of the Gli3 transcription factor to a transcriptional repressor (45).

Stage III – Full Differentiation

Further steps lead to the formation of cartilage primordia and are influenced by patterning factors such as tenascins, thrombospondins and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP)(46). Fibronectin production decreases, while collagen II, IX and XI production increase at this stage (20) (Figure 1).

Wnt signals act in concert with FGF, Shh and BMP pathways to coordinate patterning along the dorso-ventral and antero-posterior axes (47). Wnt signals are among the earliest signals required to induce production of FGFs, which act in positive feedback loops (48, 49). For example, FGF-10 induces Wnt3a, which acts via β-catenin to increase FGF-8, which then maintains FGF-10 expression (50). Among the 22 FGFs identified thus far (51), only a few have known temporal patterns. Furthermore, the physiologic ligands that activate FGF receptors (FGFRs) during chondrogenesis have been difficult to identify. It is important to investigate the expression of not only the FGF types that are ligands for FGFRs, but the temporal and spatial location of the FGFRs themselves. For example, in embryonic cartilage development, three types of fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs 1–3) are expressed in a stage-dependent pattern and play a significant role in chondrogenic differentiation. FGFR2 is clearly expressed by cells in the condensation phase whereas FGFR3 is expressed during differentiation and FGFR1 during hypertrophy (52) (Figure 1 inset).

The patterning factors Wnt, Shh, BMP, and FGF function sequentially (53). In fact, throughout chondrogenesis, the balance between BMP and FGF signaling determines the rate of proliferation, adjusting in this way the speed and pace of differentiation (54). BMPs initiate chondroprogenitor cell determination and differentiation, but also regulate the later stages of chondrocyte maturation and terminal differentiation to the hypertrophic phenotype (19). In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that BMP signaling is required both for the formation of precartilaginous condensations and for the differentiation of precursors into chondrocytes (55). Long after condensation, BMP-2, -3, -4, -5, and -7 are expressed primarily in the perichondrium and only BMP-7 is expressed in the proliferating chondrocytes (54).

Another important stimulator of chondrocyte proliferation in the growth plate is the growth hormone (GH) (56). GH exerts its effects on the growth plate predominantly through stimulation of secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1), both by liver cells and by growth plate chondrocytes (57). IGF-1 increases proliferation of differentiating chondrocytes (58), and also increases hypertrophic cell size at later stages (59). IGF-1 is produced by chondrocytes and stored within the extracellular matrix of cartilage, probably bound to proteoglycans, particularly to syndecans and IGF-1 binding proteins (60). Additional ECM components at this stage include aggrecan, which is upregulated during differentiation, and tenascin, which is reduced (32). The adhesion molecules N-cadherin and N-CAM disappear in differentiating chondrocytes and are detectable only in perichondral cells (19, 61) (Figure 1).

During embryonic chondrogenesis, perichondrial cells and early proliferative chondrocytes secrete parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), which acts on the same receptor used by parathyroid hormone (PTH). The PTH/PTHrP receptors (PPRs) are expressed at low levels by proliferating chondrocytes and at high levels by prehypertrophic chondrocytes. PTHrP acts primarily to keep proliferating chondrocytes in the proliferative pool by delaying chondrocyte transformation into prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes (62). PTHrP is engaged in a negative-feedback loop with Indian hedgehog (Ihh). PTHrP is secreted in abundance, inhibiting the production of Ihh. Towards the end of stage III, the cartilage primordia become elongated masses of cartilage tissue. Signaling between the perichondrium and already differentiated chondrocytes in the center initiates chondrocyte maturation in order to prepare a site of ossification. These chondrocytes undergo several turns of fast proliferation, and then arrest in their cell cycle.

Stage IV – Hypertrophy

The post-mitotic chondrocytes from the end of stage III change their morphology, alter their gene expression, and remodel their extracellular matrix to become hypertrophic chondrocytes (32) (Figure 1). In fact, there is a whole series of maturation steps during differentiation of committed chondrocytes to prehypertrophic, hypertrophic and matrix-mineralizing terminal chondrocytes (62). The cells undergoing hypertrophy increase in size and begin to produce a calcified matrix rich in type X collagen (56) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) (63), in contrast to proliferating and articular chondrocytes that synthesize mostly type II collagen. Hypertrophic chondrocytes express an array of terminal differentiation genes, including matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) and Runx2 and 3 that influence mineralization (64). BMP-6 is found exclusively in hypertrophic chondrocytes while BMP-2 and BMP-7 can be found in pre-hypertrophic cells as well (19, 54). The Sox9 gene turns off in hypertrophic chondrocytes (65), another example of the defined temporal gradient of factors in cartilage development. The terminally differentiated hypertrophic chondrocytes then undergo apoptosis (19, 62). Aggrecan expression, which started increasing during differentiation, continues during hypertrophy (32). After a reduction during precartilage condensation, hyaluronan is again expressed after determination of chondroprogenitors and full differentiation and is maintained through hypertrophy (20).

Chondrocyte maturation is driven from pre-hypertrophy to terminal hypertrophy by Ihh and PTHrP signaling (67). Ihh is synthesized by chondrocytes leaving the proliferative pool (pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes) and by early hypertrophic chondrocytes. Ihh binds to its receptor Ptc-1 and exerts its actions including coordination of chondrocyte proliferation and chondrocyte and osteoblast differentiation (68). When proliferation is complete, Ihh stimulates the production of PTHrP (62). In fact, the PTHrP/Ihh system undergoes major structural and functional changes in the postnatal growth plate. The hypothesis is that the embryonic Ihh-PTHrP feedback loop is maintained in the postnatal growth plate but that the source of PTHrP shifts to a more proximal location in the resting, superficial zone (69). Obviously, PTHrP and Ihh release must be closely coordinated temporally, both during prenatal and postnatal development, in order to achieve a significant level of chondrocytes proliferation prior to hypertrophic transformation.

2.2. Development of articular cartilage and synovial joints

Native cartilage development shows clear temporal dependency of expression of various growth factors and ECM components, both in the growth plate and the articular–epiphyseal growth cartilage. Synovial joints develop concomitantly with the skeletal elements that they articulate (70, 71), in step-wise manner.

In the first step, called joint determination, skeletogenic cells are directed to the articular fate. These articular chondrocytes develop from articular progenitor cells, which originate from the same pool of mesenchymal cells as growth plate chondrocytes and osteoblasts They express Sox5/6/9 as do adjacent chondrogenic cells, but they also express the genes for TGF-β receptor-2 (TGFβr2), Wnt canonical ligands (Wnt4, Wnt9a/14, and Wnt16), and growth differentiation factor-5 (GDF5) (72, 73). The TGFβr2/Wnt/GDF5 signaling cascade is required and sufficient to coax articular progenitors to the definite articular fate (74, 75). The effect of this signaling cascade is the formation of presumptive joint regions called interzones that are composed of highly condensed cells, among which the precursors of non-cartilaginous tissues down-regulate expression of Sox5/6/9 (76).

In the next step, joint morphogenesis, articular cells differentiate and develop into joint structures (77).

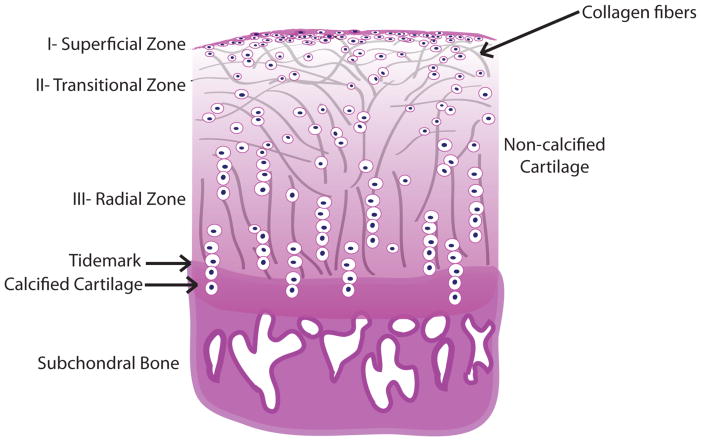

No matter what the location or stage of development, chondrocytes in growth cartilage are arranged in morphologically distinct zones (17), with stratification that reflects the temporal gradients in cell differentiation. Another temporal effect is that cartilage within growth plate disappears at the time of adolescence (62, 78). Fully formed AC is structurally divided into three zones, each with a specific cellular morphology and arrangement of the type II collagen fibers (Figure 2). Chondrocytes in the superficial or tangential zone are small and flat, with collagen fibrils arranged parallel to the surface. In the other zones, chondrocytes maintain a characteristic round shape. The intermediate or transitional zone is the thickest and composed of proliferating cells. In this region, the collagen fibers are less organized, but are typically in a tilted orientation relative to the surface. In the deep basal or radial zone, chondrocytes and collagen fibers are oriented in vertical columns perpendicular to the surface (79) (Figure 2). The deep layer of cartilage also contains more proteoglycans (80). Such matrix organization results in different mechanical properties. The combination of the layers is what provides cartilage its unique mechanical properties and overall functionality as a smooth, lubricating surface that absorbs and transmits mechanical forces (80).

Figure 2. Articular cartilage stratification zones correlate to the cell differentiation stages.

Chondrocytes in the most superficial or tangential zone (Zone I) are small, immature and flattened, and collagen type II fibrils are arranged tangentially to the surface. Transitional zone (Zone II) is composed of proliferating spherical chondrocytes, less strongly bound in the ECM with collagen fibers oriented slightly perpendicularly to the surface. In the thickest, deep radial zone (Zone III), chondrocytes are the largest, with hypertrophic phenotype and usually arranged in lacunae larger than in the previous zone. Both chondrocytes and collagen fibers are oriented in vertical columns perpendicular to the subchondral plate. Below are the tidemark, a basophilic line which straddles the boundary between calcified and uncalcified cartilage; calcified cartilage where the chondrocytes undergo apoptosis and the subchondral bone.

The main structural feature of the AC is the hyaline component, characterized by its glassy appearance when viewed under polarized light microscopy. The non-collagenous fraction of the cartilage is composed of the proteoglycans, link protein, and interfibrillar proteins like COMP or decorin. Aggrecan accounts for about 90% of the proteoglycan content, and the rest is comprised of fibromodulin, lumican, biglycan, and perlecan (61). The interface of AC and subchondral bone is bridged by calcified cartilage, which is separated from the hyaline tissue by a proteoglycan-depleted tidemark (81).

3. Biomimetic approach to cartilage tissue engineering using stem cells

Tissue engineering strategies that aim to recapitulate some temporal aspects of native AC development, may be more successful than those that disregard the temporal control of tissue formation. To estimate the level of recapitulation that has been achieved so far, we begin with a comparison of studies that engineer AC from chondrocytes (82) and from human MSCs (hMSCs) (11, 83). Cartilage engineered from chondrocytes typically demonstrates a fibrocartilage phenotype, while MSC-derived cartilaginous cells are less likely to dedifferentiate into the fibroblast-like phenotype when expanded in vitro (84). However, despite the demonstrated potential of MSCs for chondrogenic differentiation, the long-term efficacy of MSC-engineered cartilage has not yet been established. In one study, cartilage engineered from MSCs formed less matrix with lower mechanical properties than that engineered from chondrocytes (83), but in another study, MSC-engineered cartilage was superior (85). The source of MSCs (bone marrow, adipose, etc.) and the seeding density can also affect the quality of engineered cartilage (86).

A study investigated the chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs in alginate gel discs at four distinct time points ranging from 0 to 24 days, using traditionally defined markers as well as global gene expression profiles (7). Time-dependent accumulations of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), aggrecan, and type II collagen were observed in constructs maintained in serum-free chondrogenic media, but not in media supplemented with fetal bovine serum. Gene expression profiles demonstrated a characteristic temporal pattern of chondrogenic markers with four distinct stages. Gene profiles at stages III and IV were analogous to those in juvenile chondrocytes. Gene ontology analyses demonstrated a specific expression pattern of several putative novel marker genes (7). Interestingly, when donor-matched hMSCs and chondrocytes were maintained under identical chondrogenic conditions in 3D culture in vitro, differences were observed in transcriptional profiles, mechanical properties and matrix deposition (87). Using microarray analysis, 324 genes were identified as mis-expressed during chondrogenesis. These findings suggest that MSCs can be induced to undergo chondrogenic differentiation, but that they produce cartilage that is at best similar to fetal cartilage, albeit with a significant degree of gene mis-expression. Although MSCs reach the stage of juvenile chondrocytes, which would be equivalent to stage II in the native cartilage development described in Figure 1, they cannot progress into full differentiation (stage III) of native development. Although the mechanical and biochemical properties of engineered cartilage constructs improve with duration in culture, values for MSC-engineered tissues usually plateau around day 28 of culture in most protocols and remain low (7, 11).

A meritorious 8-week long study was performed by Erickson et al. (12) to compare MSC-seeded vs. chondrocyte-seeded hydrogels. Mechanical properties, measured biweekly in unconfined compression to determine equilibrium and dynamic material properties. This study has established that on day 56, the final day of culture, the equilibrium (Young’s) modulus (EY) and dynamic (G*) modulus for chondrocyte-seeded agarose constructs were ~170kPa and ~1MPa, respectively, while the corresponding values for the MSC-seeded agarose constructs were EY ~100kPa and G* ~0.15MPa. In comparison, the value of the Young’s modulus for native cartilage is in the range of 0.45 to 0.80 MPa (88).

Erickson et al. have also characterized the associated biochemical and histological construct properties. They reported that the final (day 56) chondrocyte-seeded agarose constructs contained ~1800μg of sGAG and 1200μg of collagen, while MSC-seeded agarose constructs at the same time point had s-GAG content of ~1500μg and collagen ~700μg. EY and G* were then correlated to the concentration (as a percentage of wet weight) of s-GAG and collagen in each construct for each cell type (12). For both EY and G*, the correlations for the MSC-laden constructs were less strong than those obtained for chondrocyte-laden constructs (p<0.05) (12).

Another study documented inferior biochemical composition of matrix proteins in hMSC-engineered cartilage when compared to adult and fetal cartilage (11) by reporting the contents of GAG (in μg/mg dry weight) for adult, fetal and MSC-engineered cartilage of ~170, ~470 and ~70, respectively. The corresponding contents of type II collagen (in μg/mg dry weight) were: ~470, ~250 and ~15, respectively (11).

Evidently, we have not yet succeeded in recapitulating temporal changes in gene expression during engineered cartilage formation. This is confirmed by the lack of a mature chondrocyte phenotype in engineered constructs. MSC-based constructs for cartilage regeneration have yet to achieve functional properties approaching that of the native tissue, or even that of chondrocyte-based constructs cultured identically (87). The failure of traditional tissue engineering protocols using stem cells may be the lack of focus on the crucial temporal aspects of chondrogenesis.

4. Stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering

4.1. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and embryonic germ cells (hEGCs)

hESCs and hEGCs have also been manipulated towards chondrogenesis (89–92) and the formation of cartilaginous tissues (93, 94) (Figure 3). Cell lines with long-term and robust proliferation have been selected and generated from embryoid bodies (EBs) (95, 96). However, the fraction of chondrocytes arising from spontaneous differentiation of EBs in vitro is very low (89, 93). Kim et al. have described for the first time in vitro musculoskeletal differentiation of cells derived from EBs (97). These cells were clustered into pellets to mimic the mesenchymal condensation process during limb development. Differentiated cells showed up-regulation of a numerous musculoskeletal genes, but did not assemble tissue specific matrix, although pellets treated with TGFβ3 did exhibit a time-dependent increase in collagen and proteoglycan production.

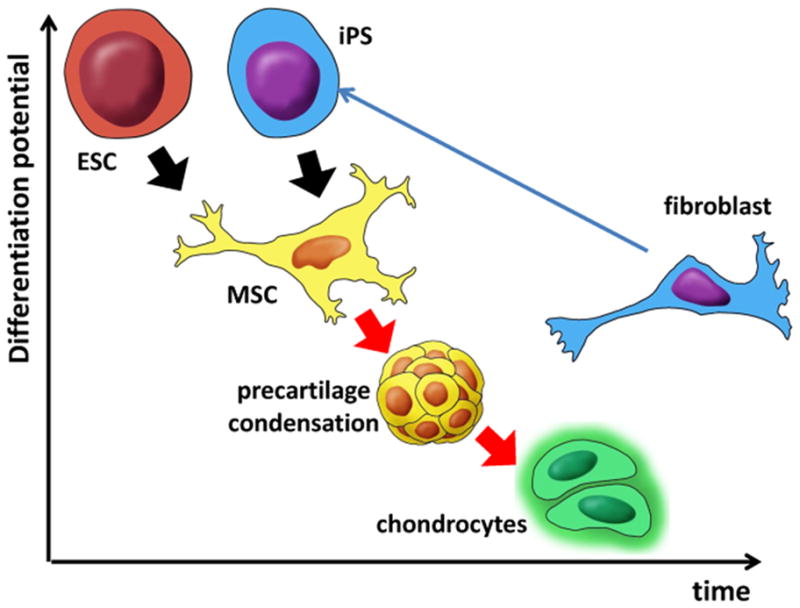

Figure 3. Stages in chondrogenic differentiation of embryonic and iPS cells.

Pluripotent cell types (ESC and iPS) have to differentiate into multipotent MSCs in order to form precartilage condensation required for efficient further differentiation into chondrocytes. Chondrocytes, as fully differentiated cells, have lower differentiation potential compared to fibroblasts which can still be induced to differentiation as well as to conversion to iPS cells.

Self-aggregation, a process that mimics the pre-cartilage condensation stage in native embryonic development, enhanced chondrogenic differentiation to the extent that homogenous hyaline cartilage could be generated after 63 population doublings (98). The cells were also found to differentiate when delivered in vivo using scaffolds. These data confirm that mesenchymal cell condensation is a major event in the commitment of stem cells to the chondrogenic lineage (Figure 1).

It appears likely that in order to increase the efficiency of chondrogenesis from hESCs one must direct differentiation of hESCs first into the MSC-like phenotype and allow mesenchymal cell condensation (precartilage condensation) to take place. This strategy is supported by step-wise protocols to achieve MSC differentiation and then chondrogenesis. To date, several reports have described the derivation of MSCs from hESCs for subsequent chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage tissue engineering (99–102). The implanted hESC-derived mesenchymal cells gave rise to homogeneous, well-differentiated tissues exclusively of mesenchymal origin and without teratoma formation (103). This approach of directed differentiation of hECSs into MSCs prior to initiating chondrogenesis is becoming state-of-the-art method in cartilage tissue engineering (Figure 3).

Recent studies indicate that the chondrogenic phenotype can be induced by avoiding EB formation (104) and by dissociating cells from the EBs and then utilizing aggregation to stimulate chondrogenesis (105). Nakagawa et al. used a direct hESC plating method to avoid EB formation followed by cultivation of hESCs in a pellet culture system for 14 days in chondrogenic medium with or without TGF-β, and reported increased expression of the genes for aggrecan and collagen II, and increased GAG levels (106). Cartilage constructs engineered using cells that were enzymatically dissociated from EBs outperformed constructs based on EBs, by demonstrating greater production of collagen- and GAG-rich matrix and higher instantaneous modulus (90). These findings indicate once again that self-aggregation of individual cells is important for the process of in vitro chondrogenesis, consistent with the developmental steps observed in native chondrogenesis (Figure 1 – stage I).

After it was recognized that hESCs must go through the stage of aggregation and condensation in order to achieve efficient chondrogenesis (91), various protocols were reported to differentiate hESCs toward multipotent mesenchymal cell lineages and then chondrocytes by using supplemental factors (89, 92, 96, 107), co-culturing with chondrocytes (108–110) and immature chondroprogenitors (111), or using pellet culture (112–116). However, none of these methods achieved high yields of chondrocytes. Significant improvement was achieved with step-wise (directed) differentiation of hESCs (117) through the primitive streak–mesendoderm (step I) and mesoderm intermediates (step II) to a chondrocyte population (step III). This protocol took advantage of the temporal pattern of marker gene expression, recapitulating de facto the steps of in vivo chondrogenesis. The established timeline for directed differentiation of hESC was 1–4 days of differentiation for step I, 5–9 days for step II and 9–14 days for step III (117).

Yamashita et al. attempted to recapitulate the five-stage process of endochondral ossification starting from mouse ESCs (94): (1) Cell condensation and aggregate formation (days 0–5), (2) Differentiation into chondrocytes and fibril formation within spherical aggregates (day 5–15), (3) Deposition of cartilaginous ECM and cartilage formation (day 15–30), (4) Apoptosis, hypertrophy and/or degradation of cartilage (day 3–40), and (5) Bone formation (day 50–60). This approach to bone engineering through endochondral ossification, in which ESCs first deposit cartilage to serve as a template for ossification, is lately gaining attention in the field of skeletal tissue engineering (93).

4.2. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS)

Ever since Takahashi and Yamanaka showed for the first time that ectopic expression of a defined set of genetic factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) can reprogram somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells resembling hESCs (118) (Figure 3), iPS cells have become a highly investigated topic in all areas of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Human iPS cells were derived from fetal neural stem (FNS) cells by transfection with a polycistronic plasmid vector carrying the mouse Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc genes or a plasmid expressing the human OCT4 gene, and directed these cells to form cartilaginous tissue in vitro (119). Another study investigated induction of mesenchymal progenitor cells with chondrogenic properties from mouse iPS cells (120), and suggested that it is advantageous to induce iPS cells to differentiate first into mesenchymal cells prior to initiating chondrogenic differentiation, (Figure 3).

Precartilage mesenchymal condensation may prove to be crucial for the recapitulation of the native cartilage development and needs to be investigated in more detail. At this point, iPS cells do not present an established cell source for articular cartilage engineering. As long as the c-Myc and Klf4 transgenes are present in the induced cells, it is possible that these cells may eventually become tumorigenic. To reduce this risk, c-Myc and Klf4 constructs should be transiently expressed to induce pluripotency and eliminated after a sufficient number of induced cells are produced.

4.3. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

The proliferation and chondrogenic capacity of hMSCs makes them an attractive cell source for cartilage tissue engineering (Figure 3). hMSCs have been isolated from bone marrow (121), adipose tissue (122–124), synovial membrane (125), trabecular bone (48, 126), and umbilical cord (127). Chondrogenic differentiation can be stimulated via various protocols such as the supplementation of soluble growth factors, optimization of the 3D microenvironment, mechanical stimulation, and transfer of chondrogenic genes (8, 9, 12, 128). However, only recently has the need to incorporate the temporal aspect into differentiation protocols been recognized. Current procotols can induce differentiation of MSCs into juvenile chondrocytes (stage II in the native cartilage development), but cannot accommodate progression to full differentiation.

Another recent study compared cartilage engineered from hMSCs, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hASCs), and dedifferentiated chondrocytes (C28/I2 line). All cells were transfected with the Sox5/6/9 genes (Sox Trio) and encapsulated in fibrin hydrogel to evaluate the chondrogenic potential in vitro and in vivo (9). Chondrogenic genes and proteins were more highly expressed in Sox Trio-expressing cells than in untransfected cells. However, there were differences in the expression of specific genes (aggrecan, collagen II, COMP, Sox9) detected in vitro among the three types of cells, possibly due to the different developmental levels of the cells prior to Sox Trio transfection. Similar results were obtained in vivo, except that transfected hASCs did not express chondrogenic markers, again highlighting differences among the cell types. During development, Sox genes turn on/off at different stages, and this temporal sensitivity of gene expression should be taken into account in transfection studies.

It is also important to analyze functional markers of cartilage formation in addition to gene expression profiles. Some studies that claim to achieve successful differentiation of hMSCs into mature chondrocytes have not examined the ECM composition and mechanical properties with comparison to native cartilage (9). Hence, the evidence of full differentiation of MSCs to mature chondrocytes is still inconclusive.

Once full differentiation is achieved, another aspect to consider will be to preserve fully differentiated chondrocytes from progressing to hypertrophy (i.e. stage IV). Several factors have been identified that might serve such a function. For example, the non-canonical Wnt5b factor has been shown to inhibit chondrocyte hypertrophy and expression of type X collagen (129). Also, the expression of Sox5/6/9 could be down-regulated at this stage to mimic the behavior of cartilaginous precursors in vivo (76).

5. Timing of exposure to growth factors in cartilage tissue engineering

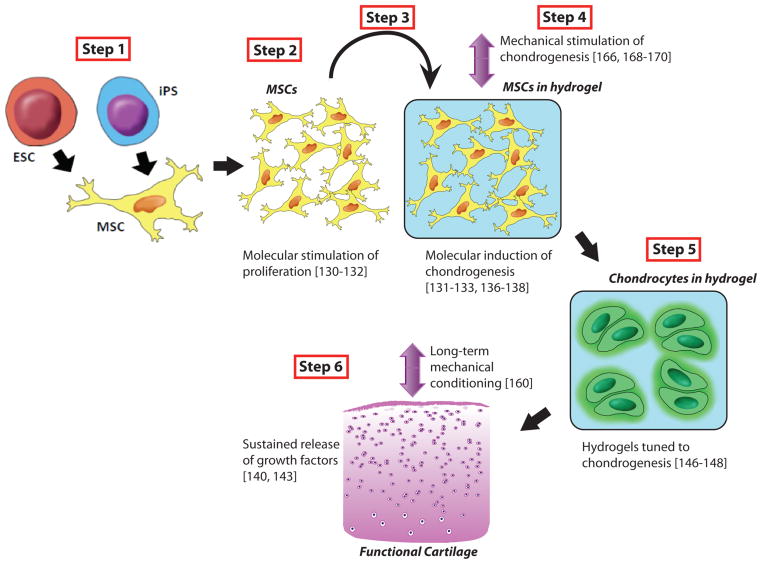

The sequential addition of growth factors to cell culture medium has been useful in stimulating chondrogenesis of chondrocytes or stem cells in vitro (Figure 4). The addition of growth factors in a sequence similar to native development, e.g. basic FGF (bFGF) or FGF2 followed by BMP2 or IGF1, TGFβ2 or TGFβ3 (Figure 1), increased proliferation and subsequent chondrogenic differentiation (130–135). Similarly, exposure of chondrocytes seeded in agarose gels to TGFβ3 for 2 weeks followed by unsupplemented culture medium resulted in enhanced cartilage formation and mechanical properties compared to prolonged exposure to TGFβ3 (136). The exposure of MSCs in poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels to TGFβ1 for just 7 days resulted in enhanced proteoglycan production compared to prolonged culture, but decreased collagen production (137). These data emphasize the importance of controlled duration of growth factor application. Because various factors in native development switch on and off at different stages, understanding of these temporal changes is crucial for their utilization in tissue engineering (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Proposed steps in the biomimetic protocol for cartilage tissue engineering.

Step 1: Directed differentiation of hESCs or iPS into MSCs-like cells (if the starting cell type is already MSC-like then this step is to be omitted). Step 2: Molecular stimulation of proliferation where MSC-like cells should be induced to undergo aggregation and subsequent condensation and determination. Starting with Step 2, the cells should be in 3D environment i.e in hydrogels or scaffolds to achieve the most similar native-like physical environment. Step 3: The cells are presumably at the level of immature chondrocytes, and molecular induction of full chondrogenesis should be implemented. Step 4: Mechanical stimulation. Step 5: Hydrogel degradation (see details in text). Step 6: Long-term mechanical conditioning.

The stage of MSC differentiation at which the growth factor is added also affects chondrogenesis. The prolonged exposure of MSCs in pellet culture to FGF2 caused a reduction in GAG production relative to unsupplemented culture medium, but a slight increase in GAG deposition was observed when it was added at day 21 of culture (138). The addition of FGF9 at early stages of differentiation (days 3–14) resulted in an increase in GAG deposition, but prolonged FGF9 caused a decrease in GAG deposition (138). This temporal profile matches that seen in development where FGF9 is predominantly secreted during early stages of differentiation (stage II) (Figure 1). The addition of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) to MSCs and ASCs after 2-weeks of chondrogenic differentiation increased ECM production and decreased cell hypertrophy (139). This effect is consistent with the native development, where PTHrP exerts its pro-chondrogenic effects at the later stages of development (stage III and IV) (Figure 1).

Controlled release of cytokines from hydrogels or scaffolds has been utilized to continuously expose cells to stimulatory growth factors in vivo (Figure 4). The temporal release profile affects the chondrogenic response (140–142). For example, a slower rate can prolong the biological activity of a drug or growth factor (140), but a rate that is too slow may result in an ineffective daily dose (141). Interestingly, the sequential release of TGFβ1 followed by IGF1, which is observed in chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs, did not result in enhanced cartilage repair in an osteochondral defect in rabbits compared to the delivery of IGF1 alone (143). These results highlight the need to carefully evaluate the effects of release kinetics on cartilage repair.

The rate of hydrogel degradation also affects cartilage formation (Figure 4). The hydrogels must degrade at a sufficient rate to allow matrix elaboration while maintaining support for seeded cells and retention of synthesized proteins (144, 145). The degradation of hydrogels can be coupled to cartilage formation by incorporating linkages that are selectively degradable by cartilage-specific enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which have temporally defined expression in native development, so that degradation is concomitant with matrix evolution (146). After determining that the expression of MMP-7 coincides with differentiation of hMSCs to chondrocytes, Bahney et al. designed poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels crosslinked with MMP7-sensitive peptides (147). After 12 weeks in vitro, the engineered cartilage in these hydrogels achieved a higher dynamic modulus than nondegrading controls, despite lower GAG contents, suggesting that the structure of the engineered cartilage was more functionally similar to native cartilage. The degradation of PEG-based hydrogels that are crosslinked with photolabile moieties can be controlled by the external application of light (148). The adhesive peptide RGDS, a component of fibronectin, was incorporated into the PEG hydrogels and released after 10 days by the application of light, a temporal expression profile that matches the expression of fibronectin by MSCs during development (Figure 1). Encapsulated MSCs produced a four-fold higher level of matrix components than MSCs encapsulated in hydrogels with persistently-expressed RGDS.

6. Temporal aspects of mechanical stimulation

Mechanotransduction, the translation of mechanical stimuli into cellular responses, is important in cartilage tissue homeostasis (149–151). Mechanical stimulation applied at physiological strains and frequencies to chondrocytes and stem cells can result in increased chondrogenesis. While static loading generally inhibits chondrogenesis (152–156), the effects of dynamic loading on cartilage formation are more complex. The response of chondrogenic cells can be affected by the magnitude, frequency, duration, and timing of initiation of dynamic loading cycles (153, 157–160). Both the catabolic and anabolic effects of mechanical stimulation on chondrocytes contribute to matrix synthesis and remodeling (149, 159, 161, 162).

Mechanical stimuli were shown to contribute to chondrogenesis in the developing embryo (163, 164). Dynamic loading of MSC-laden gels in vitro increases chondrogenic gene expression through the TGFβ signaling pathway (157, 165–171). It seems important to follow a native-like pattern of growth factor addition and mechanical stimulation. For immature chondrocytes, stimulation with growth factors followed by mechanical stimulation (while discontinuing growth factor application) proved to be most efficient as indicated by the study of Lima et al. where the sequential application of TGFβ3 and dynamic loading was shown to enhance cartilage formation in immature chondrocytes-seeded gels (172). In this study, Lima et al. report that the sequential application of physiologic deformational loading after culturing with the growth factor TGFβ3 (for 2–3 weeks) yielded significantly stiffer chondrocyte-seeded agarose constructs than cultures in which deformational loading was applied during the initial 2–3 week TGFβ3 exposure period. Using this culture protocol, engineered constructs were found to reach Young’s modulus and GAG levels similar to that of native (parent) articular cartilage after only 42 days of culture.

Taking into account that TGFβ3 secretion has temporally defined profile in native development, as described earlier (Figure 1), it is not surprising that the protocol that employed defined sequences of TGFβ3 application and subsequent mechanical stimulation, in a biomimetic setting, yielded more functional engineered cartilage than the simultaneous application protocol. It is also important to emphasize that Lima et al. used immature chondrocytes, most likely in the Stage II of the developmental sequence described earlier (Figure 1), which are most responsive to TGFβ application.

Consistent with previous findings, long-term dynamic loading initiated soon after MSC encapsulation in the presence of TGFβ3 reduced the mechanical properties of constructs compared to free-swelling controls (173). Loading initiated before chondrogenesis decreased functional maturation of MSC-based constructs, although chondrogenic gene expression increased. In contrast, loading initiated after chondrogenesis and matrix elaboration further improved the mechanical properties of MSC-based constructs, but only when TGFβ3 levels were maintained and under specific loading parameters (160). Although matrix quantity was not affected by dynamic compression, matrix distribution was significantly improved on the micro- (pericellular) and macro- (bulk construct) scales. These results demonstrate that dynamic compressive loading initiated after a sufficient period of chondroinduction and with sustained TGF-β exposure can enhance matrix distribution and the mechanical properties of MSC-seeded constructs (160).

In early cartilage development, cells are not subjected immediately to strong deformational loading, they first have to undergo several stages of differentiation influenced by different growth and differentiation factors. The nuclei of undifferentiated stem cells deform more readily than that of differentiated cells (174), which contributes to the fact that the differentiation status of MSCs plays a role in how these cells perceive external mechanical stimulation. Cell-matrix interactions may also affect load-induced response. Agarose, one of the commonly used hydrogels for chondrogenic cell-seeded constructs, is an inert material, so cell-matrix interactions only emerge as MSCs differentiate and generate local ECM (160). With matrix elaboration, the physical environment of the cells under dynamic compression is also altered (175). As construct composition shifts to a denser, cartilage-like matrix of proteoglycans and collagen and permeability decreases, the stresses induced by dynamic compression are higher and largely borne through fluid pressurization (176).

In order to develop a biomimetic approach for stem cell-based cartilage engineering, we believe that directed, step-wise protocols should be implemented. We suggest that Step 1 should comprise directed differentiation of hESCs or iPS cells into MSCs-like cells (if the starting cell type is already MSC-like then this step is to be omitted) (Figure 4). Step 2 entails molecular stimulation of proliferation where MSC-like cells should be induced to undergo aggregation (Stage I of native development) and subsequent condensation and determination (Stage II) (Figure 4). Starting with Step 2, the cells should be in a scaffold providing a native-like 3D environment (Figure 4). At Step 3, the cells are presumably at the level of immature chondrocytes, and molecular induction of full chondrogenesis should be implemented (Figure 4). This should lead to the acquisition of cells of a phenotype similar to those in Stage III of native development. This step is followed by mechanical stimulation (Step 4) (Figure 4). As described earlier, recent findings allowed for formation of tunable hydrogels in which degradation of hydrogel can be coupled to cartilage formation by incorporating linkages that are selectively degradable by cartilage-specific enzymes such as MMPs or by extrinsic factors such as light. Step 5 in our proposed temporally-defined biomimetic protocol would comprise carefully controlled hydrogel degradation (Figure 4). Step 6 should theoretically comprise long-term mechanical conditioning to result in the development of functional engineered cartilage (Figure 4).

Currently, cartilage tissue with mechanical properties approaching those of native tissue has been engineered from immature and mature chondrocytes (158, 172), but not from stem cells. In order to improve the efficiency of stem cell-based cartilage engineering, the application of growth factors has to be performed in strictly temporally controlled manner coordinated with mechanical stimulation. In practice, this implies pre-culture time when growth factors will be applied prior to dynamic compression of MSC- or ESC-based constructs (165, 168). Such an approach will allow the cells to reach the differentiation level of immature chondrocytes (stage II in native development), which is appropriate for the start of mechanical stimulation.

7. New perspective targets for temporal modulation in cartilage engineering

Adult articular cartilage is a physiologically hypoxic tissue with a gradient of oxygen tension ranging from <10% at the cartilage surface to <1% in the deepest layers (178). In contrast, the growth plate contains three different components: cartilage subdivided into various histological zones, a bony component (metaphysis), and a fibrous compartment surrounding the periphery of the plate, each with its distinct vascular pattern and oxygen concentration profile (177).

Within the cartilage component, the proliferative zone is highly vascularized supplying the cells with nutrients for cell division and matrix production. The oxygen tension within this zone is approximately 7.5%. In contrast, oxygen concentrations within the avascular hypertrophic zone of the cartilage component are only approximately 3.2% (177). Oxygen tension gradients may play a crucial role during the formation of the tissue and hence should be taken into account when designing protocols for cartilage tissue engineering, not only concerning the oxygen tension but also the spatial and temporal profile of gradient formation.

Lewis at al (179) have presented a mathematical model that describes the interaction between the spatially and temporally evolving oxygen profiles and cell distributions within tissue-engineered cartilaginous constructs at the early stages of development. Theoretical predictions for oxygen and cell distributions were compared with experimental data, to determine that at low cell densities the oxygen profile tends to be spatially uniform, such that proliferation is uniform in space and exponential in time. However, as the cell population increases, the oxygen consumption rate increases, causing a gradient in oxygen tension to form and creating regions of low oxygen concentrations. The steepness of the oxygen gradient is further enhanced as the cells continue to proliferate in the peripheral regions relatively rich in oxygen. Interestingly, cell-scaffold constructs that rely solely on diffusion for their supply of oxygen will always produce proliferation-dominated regions near the outer edge of the scaffold, leading to inhomogeneous cell distribution within the construct.

This study only considered the early stages of tissue growth in engineered scaffolds (the first 14 days), while Malda et al. (180) collected similar data extending to 41 days. At the beginning of in vitro culture, the oxygen gradients were steeper in constructs than in native tissue, and gradually approached native tissue over the course of culture. A mathematical model was developed to yield oxygen profiles within cartilage explants and tissue-engineered constructs. Using such mathematical models to predict local oxygen tensions in tissue-engineered cartilage constructs is one way to mitigate oxygen gradients that may otherwise influence the cell distribution and differentiation within the construct.

We propose that cartilage engineering should not be focused on avoidance but rather on establishment of control over formation of the oxygen gradients, because oxygen gradients are present in native tissue and during embryonic development. The oxygen gradients could be minimized by several factors. These factors include a less tortuous and more open scaffold geometry (177) and enhancement of the nutrient exchange by dynamic culturing techniques (181, 182) or applying mechanical forces to the construct (183, 184).

Given that normal articular cartilage is hypoxic, chondrocytes have a specific and adapted response to low oxygen environment. Adaptation to hypoxia is controlled by the oxygen-sensitive master transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) (185). In general, it has been found that low oxygen tension induces the production of cartilage specific components such as collagen type II and proteoglycans and slows down age-related changes of composition and structure of the ECM, whereas hyperoxia disturbs the chondrocyte metabolism and inhibits the production of proteoglycans (177).

It has been established that hypoxia enhances chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (186–188). It was suggested that hypoxia, like cell aggregation and TGF-β delivery, may be crucial for complete chondrogenesis (189). The use of micropellets reduced the formation of oxygen gradients within the aggregates, resulting in a more homogeneous and controlled microenvironment. Numerous studies are being conducted to optimize the oxygen culture conditions in cartilage tissue engineering using both chondrocytes and MSCs. We advise the reader to address relevant reviews by Murphy et al. and Lafont. (185, 186).

Recent studies expolored the utilization of microRNAs (miRNAs) for the control of oxygen tension gradients in cartilage tissue engineering. Adaptation to hypoxia is an essential cellular response controlled by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 expression is also controlled by specific miRNAs and, in turn, controls the expression of other miRNAs, which fine-tune adaptation to low oxygen tension (190). However, miRNAs are not only involved in oxygen-related mechanisms, but are biological signals that can be used for directing chondrogenic differentiation in engineered constructs. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, 21–25nt in length, noncoding RNAs that can mediate the function of mRNAs in translating a protein via their target region. Most miRNAs are specifically targeted toward particular mRNAs, therefore, the regulation of these mRNAs is very specific as well. While only a select number of miRNA targets has been identified, the use of miRNAs was show to enhance direct cellular function (191).

A very informative review article on osteo-chondral differentiation from stem cells with focus on phenotype acquisition regulated by microRNAs, suggest that a successful approach to engineering replacement of bone and cartilage maybe to target a set of microRNAs using precursor miRNA (pre-miRNAs) and/or chemically engineered oligonucleotides used to silence endogenous microRNAs (antago-miRNAs) modulating selected transcription factors into polycistronic vector constructs to ensure acquisition of proper characteristics of engineered osteoblasts or chondrocytes (192).

Another study investigated miRNA expression profiles in the different zones of articular cartilage as well as between regions subjected to different levels of weight-bearing stresses (193). Two miRNAs as part of a subset of differentially expressed miRNA that were up-regulated in articular cartilage in the greater weight-bearing location. Additionally, three other miRNAs were down-regulated in monolayers of chondrocytes as compared with levelwere identified s determined directly from intact native cartilage. Taken together, these data implicate miRNA in the maintenance of articular cartilage homeostasis and are therefore targets for articular cartilage tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

We believe that one of the avenues for further investigation in cartilage tissue engineering can be temporal modulation of the delivery of microRNA and/or pre-miRNAs and antago-miRNAs. In this context, it is of interest to review a study that identified microRNA profiles of rat articular cartilage at different developmental stages (194). Three small RNA libraries were constructed from the femoral head cartilage of Sprague-Dawley rats at postnatal day 0, day 21 and day 42 and sequenced by a deep sequencing approach. Then a bioinformatics approach was employed to distinguish genuine miRNAs from small RNAs represented in the mass sequencing data.

Forty-six, fifty-two and fifty-six miRNA genes were identified from three small RNA libraries, respectively, and 86 novel miRNA candidate genes were found simultaneously. In addition, 23 known miRNAs were up-regulated and six were down-regulated during articular cartilage development. The predicted targets of differentially expressed miRNAs were locally secreted factors and transcription factors that regulate proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes. These data indicate that miRNAs are differentially expressed in chondrocytes at different developmental stages (194).

8. Summary and research needs

The formation of complex functional tissues requires spatial and temporal control biophysical regulation of cell function. During development, different stages occur in regulated temporal gradients, which have effects on the complex intracellular phenomena as well as on the activation of various factors of the cellular microenvironment. The general approach in stem cell–based tissue engineering is to attempt to harness the cues detected in native tissue development in order to engineer a functional tissue that closely resembles the native one. The cells utilized in tissue engineering approach need to undergo a sequence of growth, differentiation and functional assembly in order to effectively reconstruct a native-like tissue (Figure 4). It is essential to have precisely defined temporal sequences for application of various cues for such processes to take place in a well-orchestrated manner.

Up to now, several notions from the native development have been utilized in cartilage engineering. The hESC are being clustered into pellets to mimic the mesenchymal condensation process during limb development and the approach of directed differentiation of hECSs and iPS into MSCs prior to initiating chondrogenesis is becoming state-of-the-art method in cartilage engineering, due to the established importance of MSC-like cell morphology and the mesenchymal precartilage condensation stage in the process of chondrogenesis (Figure 3). Furthermore, growth factor application in cartilage engineering protocols can be designed to follow the native development temporal profile.

Bioresponsive hydrogels tuned to chondrogenesis are being increasingly used in cartilage tissue engineering. Such “tuning” may be achieved by cartilage enzymes-mediated biodegradation or externally induced photodegradation, both with the goal of temporal coordination between scaffold degradation and matrix deposition. Immature chondrocytes are first stimulated with growth factors followed by mechanical stimulation (while discontinuing growth factors) instead of simultaneous application and early start mechanical stimulation. Stem cell-seeded constructs are allowed to undergo extended pre-culture time when growth factors are applied prior to dynamic compression, in order to achieve sufficient degree of differentiation before mechanical stimulation. Long-term loading is implemented only after sufficient pre-culture time.

However, we have not yet succeeded in fully recapitulating temporal changes in gene expression during engineered cartilage formation, as evidenced by the lack of a mature chondrocyte-like phenotype in the engineered constructs. MSC-based constructs have yet to achieve functional properties approaching that of the native tissue, or even that of chondrocyte-based constructs cultured under identical conditions. Further progress will likely depend on determining combinations of biochemical and mechanical stimulation and more specific timing of their application at temporally appropriate stages of chondrogenic differentiation and cartilage tissue formation. New perspective targets for temporal modulation, such as oxygen tension and microRNAs should also be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research funding (NIH grants DE016525, EB002520 and EB011869 to GVN; Fulbright Visiting Scholar grant and grant ON174028 by the Ministry of education and science of Republic of Serbia to IG), and expert help of Dr. Nebojsa Mirkovic in the preparation of figure elements.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:889–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuan RS. A second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation approach to the treatment of focal articular cartilage defects. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2007;9:109. doi: 10.1186/ar2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malicev E, Barlic A, Kregar-Velikonja N, Stražar K, Drobnic M. Cartilage from the edge of a debrided articular defect is inferior to that from a standard donor site when used for autologous chondrocyte cultivation. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British Volume. 2011;93:421–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B3.25675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ossendorf C, Steinwachs MR, Kreuz PC, Osterhoff G, Lahm A, Ducommun PP, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) for the treatment of large and complex cartilage lesions of the knee. Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology: SMARTT. 2011;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goessler UR, Bugert P, Bieback K, Baisch A, Sadick H, Verse T, et al. Expression of collagen and fiber-associated proteins in human septal cartilage during in vitro dedifferentiation. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2004;14:1015–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes AJ, Hall A, Brown L, Tubo R, Caterson B. Macromolecular organization and in vitro growth characteristics of scaffold-free neocartilage grafts. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry: Official Journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2007;55:853–66. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7210.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Wang W, Ludeman M, Cheng K, Hayami T, Lotz JC, et al. Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in three-dimensional alginate gels. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2008;14:667–80. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang NS, Im SG, Wu PB, Bichara DA, Zhao X, Randolph MA, et al. Chondrogenic priming adipose-mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage tissue regeneration. Pharmaceutical Research. 2011;28:1395–405. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang HN, Park JS, Woo DG, Jeon SY, Do HJ, Lim HY, et al. Chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells and dedifferentiated chondrocytes by transfection with SOX Trio genes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Y, Zhang F, Pang PX, Su K, Zhou R, Wang Y, et al. In vitro study of chondrocyte redifferentiation with lentiviral vector-mediated transgenic TGF-β3 and shRNA suppressing type I collagen in three-dimensional culture. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1002/term.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillel AT, Taube JM, Cornish TC, Sharma B, Halushka M, McCarthy EF, et al. Characterization of human mesenchymal stem cell-engineered cartilage: analysis of its ultrastructure, cell density and chondrocyte phenotype compared to native adult and fetal cartilage. Cells, Tissues, Organs. 2010;191:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000225985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erickson IE, Huang AH, Chung C, Li RT, Burdick JA, Mauck RL. Differential maturation and structure-function relationships in mesenchymal stem cell- and chondrocyte-seeded hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1041–52. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenas P, Moos M, Luyten FP. Developmental engineering: a new paradigm for the design and manufacturing of cell-based products. Part I: from three-dimensional cell growth to biomimetics of in vivo development. Tissue Engineering Part B, Reviews. 2009;15:381–94. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2008.0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingber DE, Mow VC, Butler D, Niklason L, Huard J, Mao J, et al. Tissue engineering and developmental biology: going biomimetic. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12:3265–83. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenas P, Moos M, Luyten FP. Developmental engineering: a new paradigm for the design and manufacturing of cell-based products. Part II: from genes to networks: tissue engineering from the viewpoint of systems biology and network science. Tissue Engineering Part B, Reviews. 2009;15:395–422. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byers PD, Brown RA. Cell columns in articular cartilage physes questioned: a review. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2006;14:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackie EJ, Ahmed YA, Tatarczuch L, Chen KS, Mirams M. Endochondral ossification: how cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2008;40:46–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen BR, Reginato AM, Wang W. Bone development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:191–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. The control of chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuan RS. Biology of developmental and regenerative skeletogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:S105–17. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000143560.41767.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre V, Bhattaram P. Vertebrate skeletogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;90:291–317. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan and CD44: modulators of chondrocyte metabolism. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:S152–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall BK, Miyake T. Divide, accumulate, differentiate: cell condensation in skeletal development revisited. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 1995;39:881–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamiya N, Watanabe H, Habuchi H, Takagi H, Shinomura T, Shimizu K, et al. Versican/PG-M regulates chondrogenesis as an extracellular matrix molecule crucial for mesenchymal condensation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:2390–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French MM, Smith SE, Akanbi K, Sanford T, Hecht J, Farach-Carson MC, et al. Expression of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan, during mouse embryogenesis and perlecan chondrogenic activity in vitro. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;145:1103–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knox SM, Whitelock JM. Perlecan: how does one molecule do so many things? Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences: CMLS. 2006;63:2435–45. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colvin JS, Feldman B, Nadeau JH, Goldfarb M, Ornitz DM. Genomic organization and embryonic expression of the mouse fibroblast growth factor 9 gene. Developmental Dynamics: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1999;216:72–88. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199909)216:1<72::AID-DVDY9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niswander L. Interplay between the molecular signals that control vertebrate limb development. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2002;46:877–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soulintzi N, Zagris N. Spatial and temporal expression of perlecan in the early chick embryo. Cells, Tissues, Organs. 2007;186:243–56. doi: 10.1159/000107948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrier E, Ronzière M-C, Bareille R, Pinzano A, Mallein-Gerin F, Freyria A-M. Analysis of collagen expression during chondrogenic induction of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechnology Letters. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0653-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christley S, Alber MS, Newman SA. Patterns of mesenchymal condensation in a multiscale, discrete stochastic model. PLoS Computational Biology. 2007;3:e76–e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shum L, Nuckolls G. The life cycle of chondrocytes in the developing skeleton. Arthritis Research. 2002;4:94–106. doi: 10.1186/ar396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuli R, Tuli S, Nandi S, Huang X, Manner PA, Hozack WJ, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-mediated chondrogenesis of human mesenchymal progenitor cells involves N-cadherin and mitogen-activated protein kinase and Wnt signaling cross-talk. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:41227–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chimal-Monroy J, Díaz de León L. Expression of N-cadherin, N-CAM, fibronectin and tenascin is stimulated by TGF-beta1, beta2, beta3 and beta5 during the formation of precartilage condensations. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 1999;43:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burdan F, Szumilo J, Korobowicz A, Farooquee R, Patel S, Patel A, et al. Morphology and physiology of the epiphyseal growth plate. Folia Histochemica Et Cytobiologica / Polish Academy of Sciences, Polish Histochemical and Cytochemical Society. 2009;47:5–16. doi: 10.2478/v10042-009-0007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nature Genetics. 1999;22:85–9. doi: 10.1038/8792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama H, Lefebvre V. Unraveling the transcriptional regulatory machinery in chondrogenesis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00774-011-0273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ornitz DM. FGF signaling in the developing endochondral skeleton. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2005;16:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z, Lavine KJ, Hung IH, Ornitz DM. FGF18 is required for early chondrocyte proliferation, hypertrophy and vascular invasion of the growth plate. Developmental Biology. 2007;302:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W-H, Lai M-T, Wu ATH, Wu C-C, Gelovani JG, Lin C-T, et al. In vitro stage-specific chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells committed to chondrocytes. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60:450–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akiyama H. Control of chondrogenesis by the transcription factor Sox9. Modern Rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association. 2008;18:213–9. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akiyama H, Chaboissier M-C, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes & Development. 2002;16:2813–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chimal-Monroy J, Rodriguez-Leon J, Montero JA, Gañan Y, Macias D, Merino R, et al. Analysis of the molecular cascade responsible for mesodermal limb chondrogenesis: Sox genes and BMP signaling. Developmental Biology. 2003;257:292–301. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill TP, Später D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Developmental Cell. 2005;8:727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barna M, Pandolfi PP, Niswander L. Gli3 and Plzf cooperate in proximal limb patterning at early stages of limb development. Nature. 2005;436:277–81. doi: 10.1038/nature03801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeLise AM, Fischer L, Tuan RS. Cellular interactions and signaling in cartilage development. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2000;8:309–34. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tickle C. Patterning systems--from one end of the limb to the other. Developmental Cell. 2003;4:449–58. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niswander L. Pattern formation: old models out on a limb. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2003;4:133–43. doi: 10.1038/nrg1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maruyama T, Mirando AJ, Deng C-X, Hsu W. The balance of WNT and FGF signaling influences mesenchymal stem cell fate during skeletal development. Science Signaling. 2010;3:ra40–ra. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tickle C, Münsterberg A. Vertebrate limb development--the early stages in chick and mouse. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2001;11:476–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Itoh N, Ornitz DM. Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends in Genetics: TIG. 2004;20:563–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hellingman CA, Koevoet W, Kops N, Farrell E, Jahr H, Liu W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors in in vitro and in vivo chondrogenesis: relating tissue engineering using adult mesenchymal stem cells to embryonic development. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2010;16:545–56. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2008.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tickle C. Molecular basis of vertebrate limb patterning. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;112:250–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minina E, Kreschel C, Naski MC, Ornitz DM, Vortkamp A. Interaction of FGF, Ihh/Pthlh, and BMP signaling integrates chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophic differentiation. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:439–49. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoon BS, Ovchinnikov DA, Yoshii I, Mishina Y, Behringer RR, Lyons KM. Bmpr1a and Bmpr1b have overlapping functions and are essential for chondrogenesis in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:5062–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500031102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackie EJ, Tatarczuch L, Mirams M. The growth plate chondrocyte and endochondral ossification. The Journal of Endocrinology. 2011 doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pass C, MacRae VE, Ahmed SF, Farquharson C. Inflammatory cytokines and the GH/IGF-I axis: novel actions on bone growth. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:119–27. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loeser RF, Pacione CA, Chubinskaya S. The combination of insulin-like growth factor 1 and osteogenic protein 1 promotes increased survival of and matrix synthesis by normal and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2188–96. doi: 10.1002/art.11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nilsson O, Marino R, De Luca F, Phillip M, Baron J. Endocrine regulation of the growth plate. Horm Res. 2005;64:157–65. doi: 10.1159/000088791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gaissmaier C, Koh JL, Weise K. Growth and differentiation factors for cartilage healing and repair. Injury. 2008;39 (Suppl 1):S88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quintana L, zur Nieden NI, Semino CE. Morphogenetic and regulatory mechanisms during developmental chondrogenesis: new paradigms for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part B, Reviews. 2009;15:29–41. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drissi H, Zuscik M, Rosier R, O’Keefe R. Transcriptional regulation of chondrocyte maturation: potential involvement of transcription factors in OA pathogenesis. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2005;26:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim HJ, Delaney JD, Kirsch T. The role of pyrophosphate/phosphate homeostasis in terminal differentiation and apoptosis of growth plate chondrocytes. Bone. 2010;47:657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Q, Eberspaecher H, Lefebvre V, De Crombrugghe B. Parallel expression of Sox9 and Col2a1 in cells undergoing chondrogenesis. Developmental Dynamics: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1997;209:377–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199708)209:4<377::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carlevaro MF, Cermelli S, Cancedda R, Descalzi Cancedda F. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in cartilage neovascularization and chondrocyte differentiation: auto-paracrine role during endochondral bone formation. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113 ( Pt 1):59–69. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirai T, Chagin AS, Kobayashi T, Mackem S, Kronenberg HM. Parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor signaling is required for maintenance of the growth plate in postnatal life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:191–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005011108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mariani FV, Martin GR. Deciphering skeletal patterning: clues from the limb. Nature. 2003;423:319–25. doi: 10.1038/nature01655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chau M, Forcinito P, Andrade AC, Hegde A, Ahn S, Lui JC, et al. Organization of the Indian Hedgehog - Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein System in the Postnatal Growth Plate. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2011 doi: 10.1530/JME-10-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pacifici M, Koyama E, Iwamoto M. Mechanisms of synovial joint and articular cartilage formation: recent advances, but many lingering mysteries. Birth Defects Research Part C, Embryo Today: Reviews. 2005;75:237–48. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pitsillides AA, Ashhurst DE. A critical evaluation of specific aspects of joint development. Developmental Dynamics: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2008;237:2284–94. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hartmann C, Tabin CJ. Wnt-14 plays a pivotal role in inducing synovial joint formation in the developing appendicular skeleton. Cell. 2001;104:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]