Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether spatial working memory (WM) is impaired in multiple sclerosis (MS), and, if it is, to localize impairment to specific cognitive subprocess(es).

Method

In Experiment 1, MS and control participants performed computerized memory-span and visuomotor tasks. WM subprocesses were taxed by manipulating (1) the requirement to remember serial order, (2) delay duration, and (3) the presence of irrelevant stimuli during target presentation. In Experiment 2, recall and recognition tests varied the difficulty of WM retrieval. In Experiment 3, an attention-cueing task tested the ability to voluntarily and rapidly reorient attention.

Results

Performance was worse for MS than for control participants in both spatial recall (Exp. 1 span: 95% CIMS = [5.11, 5.57], 95% CIControls = [5.58, 6.03], p = 0.003, 1-tailed; Exp. 2 span: 95% CIMS = [4.44, 5.54], 95% CIControls = [5.47, 6.57], p = 0.006, 1-tailed) and recognition (accuracy: 95% CIMS = [0.71, 0.81], 95% CIControls = [0.79, 0.88], p = 0.01, 1-tailed) tests. However, there was no evidence for deficits in spatiotemporal binding, maintenance, retrieval, distractor suppression, or visuomotor processing. In contrast, MS participants were abnormally slow to reorient attention (cueing effect (ms): 95% CIMS: [90, 169], 95% CIControls: [29, 107], p = 0.015, 1-tailed).

Conclusions

Results suggest that, whereas spatial WM is impaired in MS, once spatial information has been adequately encoded into WM, individuals with MS are, on average, able to maintain and retrieve this information. Impoverished encoding of spatial information, however, may be due to inefficient voluntary orienting of attention.

Keywords: short term memory, span, serial order, encoding, distraction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated disease resulting in widespread demyelination of neurons as well as cortical atrophy (Benedict et al., 2002; Morgen et al., 2006). It is one of most common neurological diseases, affecting both younger and older adults, and approximately 50% to 65% of people with MS suffer cognitive impairment (Bobholz & Rao, 2003; Rao, Leo, Bernardin, & Unverzagt, 1991). There remains, however, a need for a more comprehensive and precise characterization of cognitive deficits and abilities in people with MS because cognitive deficits significantly impact daily functioning (Kessler, Cohen, Lauer, & Kausch, 1992), current approaches to prognosis are imprecise, and cognitive rehabilitation has met with only mixed success.

Working memory (WM) deficits are among the most frequently reported sequelae of MS (Bobholz & Rao, 2003; Genova, Sumowski, Chiaravalloti, Voelbel, & DeLuca, 2009; Rao et al., 1993). WM deficits can have a significant impact on daily functioning because WM is critical for a broad range of abilities, from simply holding a telephone number in mind to problem solving and multi-tasking (Jonides et al., 2008). WM, however, is a complex construct involving multiple subprocesses. Investigating which WM subprocesses are and which are not reliably impaired should improve our understanding of the mechanisms by which MS causes cognitive dysfunction, improving prospects for better prognosis and cognitive rehabilitation.

Converging evidence from behavioral, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological studies indicates a functional dissociation between WM for verbal information, such as words and numbers, and WM for visuospatial information, such as the locations of objects (see Jonides et al., 1996 and Smith & Jonides, 1995 and Smith & Jonides, 1999 for reviews). Consistent with this dissociation, the most prominent model of WM postulated separate memory stores responsible for the rote maintenance of verbal and visuospatial information (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974, see also Baddeley, 1986). Baddeley and Hitch (1974) also proposed a domain-independent “central executive” component of WM that controls and manipulates the contents of these memory stores. It has since been proposed that the central executive itself can be decomposed into multiple cognitive subprocesses.

Most previous studies of MS-related WM impairment have not attempted to isolate distinct WM subprocesses. Nevertheless, several studies have investigated MS-related impairment in verbal WM (e.g., D’Esposito et al., 1996; Forn, Belenguer, Parcet-Ibars, & Ávila, 2008; Grigsby, Ayarbe, Kravcisin, & Busenbark, 1994; Litvan et al., 1988; Parmenter, Shucard, Benedict, & Shucard, 2006; Parmenter, Shucard, & Shucard, 2007; Rao, et al., 1991; Ruchkin et al., 1994; Thornton & Raz, 1997; for reviews, see Brassington & Marsh, 1998, and Genova et al., 2009). Poor performance of individuals with MS on the paced auditory serial addition test (PASAT), in particular, has been widely reported, perhaps consistent with a deficit in the storage of verbal information in WM. However, this rather complicated test demands speeded perceptual-motor processing, attention, memory updating, and mental arithmetic, and places a heavy load on executive control processes. As a result, poor performance on the PASAT provides only coarse specificity regarding the cognitive operations that are compromised.1 D’Esposito et al. (1996), using a dual-task paradigm, concluded that it is the executive processing component of WM that is likely most impaired in MS; furthermore, dual-task performance was correlated with PASAT performance, a correlation that may reflect executive processing demands in both task paradigms. Consistent with this hypothesis, results from some studies (e.g., Rao, Hammeke, McQuillen, Khatri, & Lloyd, 1984; Rao, Leo, & St. Aubin-Faubert, 1989, Rao et al., 1993; Schulz, Kopp, Kunkel, & Faiss, 2006) employing a common, standardized measure of WM (Digit Span) suggest that MS may only minimally affect verbal WM storage. Perhaps individuals with MS typically have normal verbal storage capacity that is nevertheless masked by the greater executive processing demands of the PASAT. However, other studies (e.g., Amato, Ponziani, Siracusa, & Sorbi, 2001; Grigsby et al., 1994) have found reliably worse digit span for individuals with MS, suggesting that verbal WM capacity may be reduced as well. Alternatively, it may be the case that even the Digit Span task requires substantial executive processing. As the D’Esposito et al. (1996) study illustrates, there is a need for further deconstruction of task performance in order to identify the cognitive operations that are reliably compromised and those that are spared in MS.

It is surprising that spatial WM, in contrast, has been relatively neglected in research on MS. Based on bilateral cortical atrophy and the spread of lesions across white-matter tracts connecting distant cortical regions in both hemispheres (Arnett et al., 1994; Benedict et al., 2002; Morgen et al., 2006, Swirsky-Sacchetti et al., 1992), one would expect that spatial WM, like verbal WM, would be impaired in MS.

Although not the primary focus of previous research, findings from some studies are in fact consistent with spatial WM deficits in MS. For example, Amato et al. (2001) found that impaired performance on a spatial span task emerged relatively late in the disease course for patients with early-onset MS. In contrast, Schulz et al. (2006) found impaired spatial span performance even in the early stage of the disease. It is unclear, however, whether it is deficits in memory, attention, and/or visuomotor ability that underlie poor spatial span performance in MS. Moreover, these and other studies (e.g., Bergendal, Fredrikson, & Almkvist, 2007; DeLuca, Chelune, Tulsky, Lengenfelder, & Chiaravalloti, 2004; Foong et al., 1997; Piras et al., 2003) including standardized tests of spatial WM have provided inconsistent evidence regarding the existence of spatial WM impairment in MS, suggesting a need for a more thorough investigation of this matter.

The goals for the present study were to investigate whether MS reliably impairs spatial WM, and, if it does, to identify the specific WM subprocess(es) that are compromised. In Experiment 1, we administered computerized verbal and spatial memory-span tests to individuals with MS and healthy, age-matched control participants and included several manipulations to isolate the contributions of specific subprocesses.

Because responses in the standardized spatial span tests (finger-tapping of blocks positioned in a spatial array) require greater visuomotor control than do responses in the digit span test, it is critical to rule out any concomitant visual or motor processing deficits as the underlying source of poor performance. In Experiment 1 we therefore included a test of visuomotor processing ability that required visual detection of, and rapid manual motor responses to, target stimuli presented in a spatial array.

Experiment 1 also included three manipulations intended to tax specific cognitive operations. First, because standardized span tasks require participants to reproduce sequences of items, we investigated whether a deficit in memory for serial order might underpin poor span-task performance (see Armstrong et al., 1996; Arnett et al., 1997; Beatty & Monson, 1991). In one condition, participants were required to reproduce target items (digits or locations) in the same order in which those items were presented; in a separate condition, participants also had to reproduce target items but the order in which those items were to be reproduced was unconstrained. If individuals with MS perform poorly under serial-order requirements, but perform normally when these requirements are removed, then those results would provide evidence that a deficit in processing serial order (e.g., the binding of temporal order information to stimulus representations held in WM; Gmeindl, Walsh, & Courtney, 2011) accounts for poor span-task performance in MS.

Second, because a primary function of WM is the active maintenance of task-relevant information in a readily accessible state – a function thought to be effected by the “rehearsal” or “refreshing” of WM representations – we tested for an MS-related deficit in active maintenance by varying the length of the delay period interposed between presentation of the target sequence and the response phase. If there is a reliable deficit in active maintenance, then the disparity in performance between individuals with MS and control participants should increase with increasing delay-period duration.

Finally, a frequent complaint of individuals with MS is difficulty in focusing on the task at hand (e.g., reading mail) when confronted with potentially distracting information (e.g., spouse having a telephone conversation within earshot; see also Coolidge, Middleton, Griego, & Schmidt, 1996). We therefore tested whether increased distractibility contributes to poor memory performance in MS. In distractor conditions, task-irrelevant stimuli were presented simultaneously with target items. If individuals with MS reliably fail to suppress processing of task-irrelevant stimuli, then they should perform especially poorly, relative to control participants, when presented with distractors.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Twenty-nine individuals with MS (27 females; 23 participants with relapsing-remitting MS and six with secondary-progressive MS; mean disease duration at test = 9.3 yrs, SE = 1.8 yrs; mean age = 43.3 yrs, SE = 2.0 yrs, range = 25 to 65 yrs; mean education = 15.7 yrs, SE = 0.4 yrs, range = 12 to 21 yrs) and 31 control participants (24 females; mean participant age = 43.4 yrs, SE = 2.4 yrs, range = 25 to 70 yrs; mean education = 16.6 yrs, SE = 0.4 yrs, range = 12 to 20 yrs) were included following eligibility screening; there were no reliable differences in mean age or education level between groups. Participants were recruited from the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center and via advertisement with the Maryland chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. All MS participants had received a clinical diagnosis of relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive MS from their personal physicians prior to study entry. Exclusion criteria included known current or past neurological problems other than MS; injury resulting in loss of consciousness for > 1 min; and motor impairment (paralysis, tremor, rigidity, spasms), impaired visual acuity (e.g., due to optic neuritis), colorblindness, or hearing impairment that would preclude task completion. Individuals with MS continued their daily regimen of medication; thus, as in other studies, the possible contribution of medication to performance cannot be ruled out. All participants provided informed consent and received $20.00 per hour of participation.

Although reliable correlations between level of depression and measures of verbal WM ability have been found (Arnett et al., 1999), we excluded participants whose scores on the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; The Psychological Corporation) exceeded a cutoff of 28 (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Consequently, the mean score for control participants (4.6) fell within 0.7 standard deviations of the mean score for individuals with MS (11.4), which in turn is similar to that observed for MS samples in other studies of WM (e.g., 10.38 and 11.45 in Parmenter et al. 2006 and 2007, respectively). Nevertheless, across all participants, BDI-II score was negatively correlated with memory span (r2 = 0.19, p = 0.001). However, (1) correlations between BDI-II score and memory span were not reliably different between MS and control participants (p > 0.05), (2) the correlations between BDI-II score and memory span were not reliably different between MS and control participants for either digit span or spatial span (ps > 0.05), and (3) both across all participants and within each group separately, correlations with BDI-II score were not reliably different between spatial span and digit span (ps > 0.05). Furthermore, ANCOVAs with BDI-II score entered as a covariate confirmed reliable differences between MS and control participants for both digit span (F(2,53) = 3.87, p = 0.03) and spatial span (F(2,53) = 6.43, p = 0.003). These results indicate that level of depression accounts for some variance in memory span across all participants but is unable to account for the MS-related deficit in WM reported below.

We did not select for inclusion only those individuals with MS who evidenced impairment in WM or in general cognition (i.e., selection was blind to performance on any previous cognitive tests). In addition, two standardized neuropsychological tests of executive function, visuospatial constructional ability, visual memory, processing speed, and visuomotor skills—the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCFT, see Shin, Park, Park, Seol, & Kwon, 2006) and the Trail-Making Test (see Bowie & Harvey, 2006)—were administered to MS and control participants. These tests revealed reliable differences between groups only in the time required to complete the ROCFT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Neuropsychological test scores: Mean (SE)

| Test/Measure | MS Group | Control Group | Group Effect p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trails-A | |||

| Completion time (sec) | 34 (4) | 27 (2) | 0.18 |

| Trails-B | |||

| Completion time (sec) | 72 (5) | 61 (4) | 0.09 |

| Trails B-A (sec) | 38 (4) | 33 (4) | 0.39 |

| ROCFT-Copy | |||

| Score† | 34.3 (0.5) | 34.0 (0.7) | 0.79 |

| Completion time (sec) | 140 (10) | 101 (6) | 0.002* |

| ROCFT-Immediate Recall | |||

| Score† | 19.4 (1.1) | 22.2 (1.4) | 0.12 |

| Completion time (sec) | 124 (9) | 100 (8) | 0.04* |

Note. Trails-A = Trail-Making Test part A; Trails-B = Trail-Making Test part B; Trails B-A = Trail-Making Test part B completion time minus part A completion time; ROCFT-Copy = Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, Copy condition; ROCFT-Immediate Recall = Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, Immediate Recall condition.

Scoring criteria of Meyers and Meyers (1995). Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between MS and control groups according to independent-samples t-tests (α = 0.05).

Apparatus and Stimuli

Stimulus presentation and data collection were computerized to ensure consistent administration of the tasks (Berch, Krikorian, & Huha, 1998). In the verbal tasks, responses were made using the top-row number keys “0” through “9” on a keyboard, and, in the spatial tasks, a touch-screen (KEYTEC, Inc.) was used to record responses (in terms of pixel coordinates; Fig. 1). Participants wore headphones for auditory stimulus presentation and to minimize unintended distraction. A chinrest was positioned ~38 cm from the display to maintain constant visual angles of stimuli across participants.

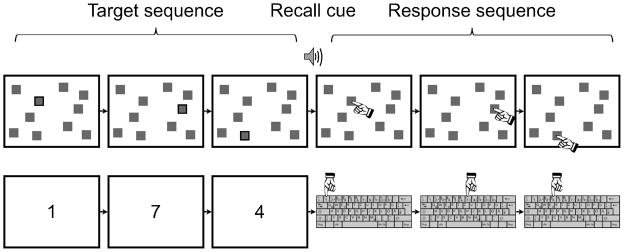

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the basic spatial (upper panel) and verbal (lower panel) task structure in Experiment 1. Following presentation of a target sequence, a tone sounded to indicate that participants should report the target items, either by touching the squares (in spatial-task blocks) or by pressing keyboard number keys (in verbal-task blocks). In this figure, spatial targets are indicated by black borders; in the experiment, spatial targets were indicated by a change in color. Target sequence length was adjusted following each trial by an adaptive staircase procedure. Three manipulations were conducted in a blocked fashion: (1) participants either were instructed to reproduce the serial order of the target items or were allowed to report the targets in any order, (2) the delay between the end of the target sequence and the recall cue was either short (0.25 s) or long (8.25 s), and (3) irrelevant auditory stimuli (noise bursts in the spatial task and words in the verbal task) time-locked to target onsets were either present or absent. See text for additional details.

Custom Matlab 7.3 code (The MathWorks, Inc.; Brainard, 1997) ensured precise timing of stimulus presentation and data collection. Visual stimuli were presented against a grey background. In the verbal tasks, white digits (0 through 9) subtending ~0.9° visual angle in width and ~1.2° in height appeared sequentially at the center of the display. In the spatial task (described below, see also Figure 1), an array of ten filled blue squares approximated the layout of blocks used in the standardized Spatial Span test (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III, The Psychological Corporation, 1997). Some squares were indicated as memory targets by changing color from blue to orange; these colors were approximately isoluminant to minimize afterimages. Each square subtended ~4.4° visual angle in width and in height, and the maximum eccentricity of the display elements was ~22.8°. For both verbal and spatial tasks, an auditory stimulus (approximately 600 Hz) provided a response cue, and another tone (approximately 300 Hz) provided acknowledgment of each detected response (key press or finger tap). In the verbal tasks, a white dash (–) subtending ~0.9° visual angle provided a visual response cue as well.

In the distraction condition of the verbal task, for each digit in the target sequence, an auditory two-syllable word (duration ~750 ms) was presented via headphones simultaneously with the onset of the digit. Two-hundred words were chosen from the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Coltheart, 1981) that had a frequency of occurrence in written English of greater than 151 per million (Kucera & Francis, 1967), and were spoken by a synthetic female voice (VoiceMX Studio 4.0, Tanseon Systems). Word order was randomized with the constraint that no words could be repeated within the same trial. In the distraction condition of the spatial task, an auditory white-noise burst (duration = 750 ms) was time-locked to the presentation of each spatial target stimulus. The auditory spatial location of white-noise bursts was varied by adjusting the relative intensity (volume) of the burst in the left and right channels; the bursts were presented at extreme left (100% left channel, 0% right channel), extreme right (0% left channel, 100% right channel), left-center (84% left channel, 16% right channel), and right-center (16% left channel, 84% right channel). The order of white-noise bursts was randomized. Identical sets of target stimuli and distractors were created for both MS and control participants prior to testing.

Procedure

At the beginning of the first session, participants completed a visuomotor-speed test. The same array of blue squares presented in the spatial span task (described below) was presented in the visuomotor-speed test. After a 2-s foreperiod at the beginning of the test, during which time the array of blue squares was presented, one square turned orange. When the participant touched the orange square (by tapping the touch-screen at the corresponding location with his or her preferred index finger), the square immediately returned to blue, and simultaneously an acknowledgement tone sounded and a different square turned orange. Participants were instructed to touch each subsequent orange square as quickly as possible during the 60-s test period. A single pseudo-random sequence of targets (that excluded immediate repetitions) was selected for presentation to all participants. Visuomotor speed was operationally defined as the number of orange squares touched during the 60-s test.

In each of three sessions, one factor of the memory-span tasks was manipulated: (1) serial-order requirements (Same Order, Any Order), (2) delay-period duration (Short, Long), or (3) presentation of distractor stimuli (Distractors Present, Distractors Absent). The order of factors manipulated was randomized across participants within each group. For each manipulation, the order of the two factor levels was counterbalanced (e.g., approximately half of the participants were given the short delay period first, approximately half were given the long delay period first). Trial blocks alternated between verbal and spatial tasks, and approximately half of the participants began with the verbal task, half with the spatial task.

In each session, participants were given task instructions and visual demonstrations. Participants then performed four practice blocks, one for each of the trial types that were relevant for a given session (e.g., for the session in which serial-order requirements were manipulated, blocks were given for Digit/Same-Order, Spatial/Same-Order, Digit/Any-Order, and Spatial/Any-Order conditions). Practice blocks contained 5 trial sequences, beginning with sequences of two target items. To provide a more reliable and precise measure of WM performance than memory span as it is commonly defined, we employed a method widely used in psychophysics research, staircase adjustment, to the length of target sequences (e.g., see Bor, Duncan, Lee, Parr, & Owen, 2006): the sequence length following a correct/incorrect response sequence was incremented/decremented by one item, respectively. Test blocks followed practice blocks, and began with sequences of three target items, subsequently adjusted by the staircase procedure. Each test block consisted of 14 trial sequences, and WM span was operationally defined as the mean sequence length of the last 10 sequences of each block, including the sequence length that would have been presented had there been a 15th sequence in the block.

To minimize the possibility of adopting a (non-optimal) strategy of remembering which items were not presented (especially in the Any-Order conditions), each item had, on average, a 0.28 probability of being repeated within the same target sequence, and participants were required to reproduce target items the correct number of times; critically, this procedure was implemented for all conditions. It should be noted that stimulus repetition is a departure from the standardized span tests. Illustrating this repetition is an example digit sequence: 4-2-9-7-2, where the digit 2 is repeated. Of importance, we constructed identical sets of pseudorandom target sequences for both the verbal and spatial tasks (see, e.g., Figure 1). In all conditions except for Any Order, a response sequence was incorrect if it did not match both the identity (digit or location) and serial order of target items. In Any-Order conditions, a response sequence was incorrect if it included items not presented in the target sequence, omitted target items, and/or included an incorrect number of repetitions.

In the verbal tasks, target sequences consisted of digits presented at the center of the screen. Each digit appeared for 750 ms, followed by a blank screen during the subsequent 250-ms inter-stimulus interval (ISI). In the spatial tasks, each location in the target sequence was indicated by one of the 10 blue squares in the array turning orange. Each orange target square (along with the other nine blue squares) was presented for 750 ms, followed by a 250-ms ISI during which all ten squares were blue. Following the target sequence, a blank screen was presented during the delay period in both verbal and spatial tasks. In all conditions except for the Long-Delay condition, 250 ms after the offset of the final stimulus in the target sequence, an auditory response-cue was presented; in the Long-Delay condition, the response cue was presented 8.25 s after the offset of the final stimulus in the target sequence. In the verbal tasks, a dash (–) providing a visual response cue appeared at the center of the screen simultaneously with the auditory response cue and persisted while the participant reported the digit sequence by pressing the number keys. In the spatial tasks, the array of blue squares was presented simultaneously with the auditory response cue and persisted while the participant reported the spatial sequence by tapping squares; squares did not change color during the response phase. For both verbal and spatial tasks, participants were instructed to respond with only their preferred index finger, and an acknowledgment tone was sounded for each detected response (button press or finger tap).

A subset of data (from the Same-Order and Any-Order conditions) have been reported previously (Gmeindl et al., 2011) for six of the control participants included here.

Results

Because the primary goal of this study was to evaluate the effects of MS on specific component process(es) of spatial WM, which has been less studied in MS than has verbal WM, we focused our analyses on spatial-task performance. However, we also conducted separate analyses of verbal-task performance to determine whether any observed impairment might extend to both domains (i.e., affecting WM for verbal as well as spatial material).

Under conditions that were most similar to standardized span tests (i.e., Same-Order, Short Delay, and Distractors Absent), individuals with MS performed reliably worse than control participants on the spatial task (95% CIMS: [5.11, 5.57], 95% CIControls: [5.58, 6.03], F(1, 58) = 8.23, partial η2 = 0.12, p = 0.003, 1-tailed; see Figure 2), supporting our primary hypothesis. Although the mean score was also lower for MS than for control participants on the verbal task, this difference was not reliable (95% CIMS: [5.94, 6.63], 95% CIControls: [6.27, 6.93], F(1, 58) = 1.76, partial η2 = 0.03, p = 0.09, 1-tailed). In the visuomotor-speed test, MS participants (95% CIMS: [74.82, 85.87 blocks]) were reliably slower than control participants (95% CIControls: [87.43, 98.12 blocks]; F(1, 58) = 10.48, partial η2 = 0.15, p = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Experiment 1: mean (±SE) span as a function of participant group and baseline task (i.e., participants were required to reproduce the serial order of target items, there was a minimal delay period prior to the recall cue, and no distractors were presented).

To examine whether a visuomotor deficit underlies this observed spatial WM impairment, we calculated within-group correlations between visuomotor speed and spatial task performance: these correlations were not reliably higher for MS (r = 0.45) than for control participants (r = 0. 41). Furthermore, within the MS group, spatial task performance was not more highly correlated with visuomotor speed than was verbal task performance (r = 0.45 vs. r = 0.49, respectively). We also conducted ANCOVAs with visuomotor speed entered as a covariate to further test whether impaired visuomotor ability accounts for the abnormally poor performance by individuals with MS. The pattern of statistical results from ANCOVA was the same as that reported above and in the rest of the results for Experiment 1 reported below: all reliable effects remained reliable, and all unreliable effects remained unreliable.

In this version of the spatial task, in which MS participants performed reliably worse than control participants (as reported above), serial-order reproduction was required. When these requirements were removed (Any Order) performance improved for both groups (MS: F(1, 28) = 89.17, partial η2 = 0.76, p < 0.001; controls: F(1, 30) = 35.85, partial η2 = 0.54, p < 0.001). However, whereas the difference in performance between groups in the Any Order condition was not reliable (F(1, 58) = 1.29, partial η2 = 0.02, p = 0.26), there remained a trend for worse performance for MS than for control participants in the Any Order condition and the corresponding group by order-condition interaction was not reliable (F(1,58) = 0.02, partial η2 < 0.01, p = 0.90; see Figure 3). In the verbal task, although performance improved for both groups (MS: F(1, 28) = 5.03, partial η2 = 0.15, p = 0.03; controls: F(1, 30) = 10.53, partial η2 = 0.26, p = 0.003) when serial-order requirements were removed, performance did not reliably differ between MS and control participants in either the Same Order or Any Order condition, nor was there a reliable group by order-condition interaction (ps > 0.05). Thus, there is no clear evidence for a common MS-related impairment in serial-order processing.

Figure 3.

Experiment 1: mean (±SE) span as a function of participant group and serial order requirements for the verbal task (Panel a) and spatial task (Panel b).

In the spatial task, performance decreased with increasing delay-period duration for both MS (F(1, 28) = 9.68, partial η2 = 0.26, p = 0.004) and control participants2 (F(1, 28) = 22.77, partial η2 = 0.45, p < 0.001). MS participants’ performance, however, was no more affected by delay-period duration than was control participants’ performance, as indicated by the absence of a group by delay interaction (F(1,56) = 0.08, partial η2 < 0.01, p = 0.77; see Figure 4). In the verbal task, there was no reliable effect of delay-period duration, performance did not reliably differ between MS and control participants in either the short-delay or long-delay condition, and there was no reliable group by delay interaction (ps > 0.05). Thus, there is no clear evidence for an MS-related impairment in working memory maintenance.

Figure 4.

Experiment 1: mean (±SE) span as a function of participant group and delay period for the verbal task (Panel a) and spatial task (Panel b).

As expected, control participants exhibited a trend for worsened spatial performance when distractor stimuli were present rather than absent (F(1, 30) = 2.86, partial η2 = 0.09, p = 0.10). Surprisingly, however, MS participants’ spatial performance reliably improved (F(1, 28) = 7.72, partial η2 = 0.22, p = 0.01). The corresponding group by distractor-condition interaction was reliable (F(1,58) = 8.46, partial η2 = 0.13, p = 0.005; see Figure 5). Anecdotally, a few MS participants and one older control participant freely reported that they found the spatial task to be easier when distractors were present. In contrast, performance in the verbal task decreased with the presentation of distractors for both MS (F(1, 28) = 6.41, partial η2 = 0.19, p = 0.02) and control participants (F(1, 30) = 9.46, partial η2 = 0.24, p = 0.004), and there was no reliable group by distractor-condition interaction (F(1,58) < 0.01, partial η2 < 0.01, p = 0.93).

Figure 5.

Experiment 1: mean (±SE) span as a function of participant group and distractor presentation for the verbal task (Panel a) and spatial task (Panel b).

Discussion

Experiment 1 revealed an MS-related impairment in spatial WM. Consistent with recent reports that reduced speed of information processing underlies the poor performance of individuals with MS on some standardized neuropsychological tests (e.g., Forn et al., 2008; Parmenter et al., 2006), visuomotor speed (which depends upon at least a simple form of information processing) was positively correlated with spatial memory span in the current study. However, visuomotor speed correlated with spatial memory span equally well for both MS and control participants. Furthermore, spatial performance remained reliably worse for MS than for control participants when we controlled for individual differences in visuomotor speed. Therefore, reduced speed of visuomotor processing alone cannot account for the observed spatial WM impairment in MS (see also Parmenter et al., 2007), although it remains possible that this impairment is related to slowed cognitive processing in general (e.g., DeLuca et al., 2004; cf. Lengenfelder et al., 2006).

Experiment 1 did not provide strong evidence for an MS-related deficit in processing serial order. As expected, the performance of both groups improved when participants were allowed to reproduce target items in any order, but the interaction of group by serial-order condition was unreliable. Thus, while some individuals with MS may have increased difficulty in processing serial order, performance differences at the group level were not sufficiently accounted for by such a deficit.

Furthermore, the results suggest that MS does not result in a rehearsal deficit. Although increasing the delay period resulted in worse spatial span performance for both groups, MS participants were not increasingly disadvantaged with increasing delay period. These results suggest that individuals with MS, on average, can adequately maintain information that has been properly encoded into WM. However, an encoding deficit may in fact limit the number or precision of item representations available for rehearsal.

One form of encoding deficit results from a degraded ability to suppress task-irrelevant information. As expected, performance in the verbal task decreased when irrelevant words were presented while participants were trying to encode digits. However, MS and control participants were apparently distracted to the same degree by these words, suggesting that MS does not result in a deficit for suppressing irrelevant verbal stimuli (cf. Coolidge et al., 1996). In contrast, MS participants, unlike control participants, performed better on the spatial WM task when distractors were presented. This counterintuitive result might reflect pacing or alerting signals provided by the white-noise bursts that allowed MS participants to compensate for a degraded ability to initiate voluntary shifts of spatial attention, a possibility addressed below.

Another possibility is that individuals with MS adequately encode spatial information into WM, but fail to retrieve it at test (see Armstrong et al., 1996; Beatty & Monson, 1991; Coolidge et al., 1996; Rao et al., 1989; cf. DeLuca, Berbieri-Berger, & Johnson, 1994; Ryan, Clark, Klonoff, Li, & Paty, 1996). In Experiment 2, therefore, we administered recognition-test as well as recall-test versions of the span tasks to investigate this possibility. Recognition tests may be more sensitive to the contents of memory than are recall tests (e.g., Chase & Ericsson, 1982) for at least two reasons. First, stimuli presented at the test phase facilitate cue-based retrieval of stimulus representations stored in memory. Second, since participants do not need to reproduce target sequences, recognition tests minimize the potential for visuomotor and sequencing processes otherwise required to produce complex response sequences (as in the standardized Spatial Span test) to interfere with memory contents. Individuals with MS, due to motor-control deficits, may be particularly susceptible to memory decay or interference during recall: slowed or inaccurate motor production may result in the loss of memory contents before they can be reported. Thus, recognition-test versions in Experiment 2 were used not only to provide a potentially more sensitive measure of WM contents by reducing the difficulty of retrieval, but also to test more directly whether impairment in motor control accounts for the abnormally poor spatial WM task performance observed for individuals with MS.

Experiment 2

Method

Participants

Seventeen MS participants (16 females; 15 participants with relapsing-remitting MS and two with secondary-progressive MS; mean disease duration at test = 7.6 yrs, SE = 1.5 yrs; mean age = 39.6 yrs, SE = 2.7 yrs, range = 24 to 67 yrs; mean education = 14.8 yrs, SE = 0.5 yrs, range = 12 to 18 yrs) and 17 age-matched control participants (16 females; mean age = 39.1 yrs, SE = 3.1 yrs, range = 19 to 68 yrs; mean education = 16.6 yrs, SE = 0.6 yrs, range = 12 to 20 yrs) provided informed consent. Control participants had slightly more education than did individuals with MS (t(30) = 2.30, p = 0.03). However, ANCOVAs with years of education entered as a covariate confirmed reliably worse performance by MS than control participants on all tasks. Five MS participants (all with relapsing-remitting MS) and one control participant had participated in Experiment 1 and were included in Experiment 2 due to convenience. Recruitment and consent procedures, exclusion criteria, and payments were the same as in Experiment 1.

Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli were the same as in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Participants performed two sets of tasks. The identical Digit/Same-Order and Spatial/Same-Order recall tasks used in Experiment 1 were given (one 14-trial test block for each stimulus type, with order counterbalanced across participants), except that a 2.25-s delay separated the offset of the target sequence from the onset of the recall cue in order to match the timing of the other conditions described below. Completion of two five-trial practice blocks, one for each stimulus type, preceded test blocks; each participant received the same stimulus type first (either verbal or spatial) for both practice blocks and test blocks of the recall tasks. In addition, recognition-test versions of these tasks were given that differed from the recall tasks in the following ways: 250 ms after presentation of the target sequence, a 1-s tone (approximately 450 Hz) was presented, followed by a 1-s delay that preceded the onset of a test sequence. The tone and delay were interposed to distinguish clearly the target sequence from the test sequence. An auditory cue (approximately 600 Hz) was presented 250 ms after the offset of the test sequence, indicating that the participant could respond. Each test sequence either (1) matched the target sequence in both identity and order, (2) contained a non-target item that replaced a target item (New Item), or (3) consisted of the target items but with the order of two temporally adjacent items reversed (New Order). Participants indicated a match between the target sequence and the test sequence by pressing the “y” keyboard key, and an identity or order mismatch by pressing the “n” key. Sequence lengths of 4, 6, and 8 items were varied pseudo-randomly across trials, and, for each sequence length, 50% of trials contained matches, 25% contained identity nonmatches, and 25% contained order nonmatches. Completion of two five-trial practice blocks, one for each stimulus type, preceded recognition test blocks. 120 recognition test trials (60 verbal, 60 spatial) were presented across four test blocks, each containing 30 trials. Stimulus type was presented in a blocked and alternating fashion (ABAB), and each participant received the same stimulus type first (either verbal or spatial) for both of his or her sets of practice and test blocks.

Data from 10 of the control participants included here have been reported previously (Gmeindl et al., 2011).

Results

As in Experiment 1, individuals with MS performed reliably worse than control participants in the spatial recall task (95% CIMS: [4.44, 5.54], 95% CIControls: [5.47, 6.57], F(1, 32) = 7.23, partial η2 = 0.18, p = 0.006, 1-tailed; see Figure 6a). The difference in performance between participant groups on the verbal recall task also was statistically significant (95% CIMS: [5.43, 6.47], 95% CIControls: [6.15, 7.18], F(1, 32) = 3.96, partial η2 = 0.11, p = 0.028, 1-tailed). The group by stimulus type (verbal, spatial) interaction was not reliable (F(1,32) = 1.43, partial η2 = 0.04, p = 0.24). These results replicate the reliably worse spatial recall performance observed for MS participants in Experiment 1; they also provide evidence for a verbal WM deficit in MS.

Figure 6.

Experiment 2: Plotted in Panel a is mean (±SE) span as a function of participant group and recall task. Plotted in Panel b is mean (±SE) proportion correct as a function of participant group and recognition task.

Of primary importance for Experiment 2, MS participants also performed reliably worse than control participants in the recognition version (see Figure 6b) of the spatial WM task (95% CIMS: [0.71, 0.81], 95% CIControls: [0.79, 0.88], F(1, 32) = 5.95, partial η2 = 0.16, p = 0.01, 1-tailed), supporting our primary hypothesis that the WM deficit is not due to visuomotor or retrieval problems. This held true for the verbal recognition task as well (95% CIMS: [0.76, 0.86], 95% CIControls: [0.83, 0.92], F(1, 32) = 4.49, partial η2 = 0.12, p = 0.02, 1-tailed). For the recognition tasks, the group by stimulus-type interaction was not reliable (F(1,32) = 0.15, partial η2 < 0.01, p = 0.70). Across stimulus types, accuracy decreased with increasing memory load (F(2,64) = 114.32, partial η2 = 0.78, p < 0.001), but there were no reliable interactions of memory load with stimulus type or group (ps > 0.05).

Performance (proportion of correct rejections) for recognition-test trials containing non-matching sequences is plotted in Figure 7. Whereas both groups of participants were reliably worse at detecting changes in serial order between target and test sequences for spatial locations than for digits [MS: F(1, 16) = 8.93, partial η2 = 0.36, p = 0.009; controls: F(1, 16) = 6.23, partial η2 = 0.28, p = 0.02], both groups detected changes in item identity between target and test sequences equally well for spatial locations versus digits [MS: F(1, 16) = 0.08, partialη2 < 0.01, p = 0.78; controls: F(1, 16) = 0.20, partial η2 = 0.01, p = 0.66]. There were no reliable interactions involving group as a factor (ps > 0.05).

Figure 7.

Experiment 2: mean (±SE) proportion of responses that were correct rejections as a function of participant group and type of nonmatching test sequence.

Discussion

Individuals with MS performed reliably worse than control participants in both the recall-test and recognition-test versions of the spatial WM task. These results suggest that the spatial WM impairment observed for individuals with MS is not due to a deficit in WM retrieval nor to degraded motor processing. Furthermore, performance on non-match trials of the recognition tests suggests that for individuals with MS, as for control participants, serial order is more readily bound to verbal than to spatial items in WM (see Gmeindl et al., 2011). MS does not appear, however, to reliably degrade spatiotemporal binding in WM, and this finding is consistent with the absence of a group by order-condition (i.e., Same Order vs. Any Order) interaction in Experiment 1.

Because the findings of Experiments 1 and 2 provide evidence against deficits in spatiotemporal binding, rehearsal, retrieval, and visuomotor processing as common sources of the spatial WM impairment evidenced in both experiments, it remains possible that individuals with MS are impaired at encoding spatial information into WM. Selectively encoding task-relevant spatial locations into WM likely relies on the judicious allocation of visual attention (e.g., Gmeindl, Nelson, Wiggin, & Reuter-Lorenz, in press), and we therefore hypothesized that a deficit in the voluntary allocation of attention underlies MS participants’ poor spatial task performance. In Experiment 3 we administered a modified version (cf. Prinzmetal, McCool, & Park, 2005) of a test used to measure the ability to rapidly and voluntarily allocate spatial attention (Posner 1980; Posner, Cohen, & Rafal, 1982). In this paradigm, to discriminate the identity of a target letter appearing among flanking distractor items (Figure 8), attention must be directed to the target. In one condition, attention is first directed away from the relevant location towards a highly salient (invalid) visual cue, and therefore participants must subsequently voluntarily reorient attention to the relevant location. RT in this condition is compared to the RT measured when the (valid) visual cue appears at the location of the upcoming target. In the latter condition, participants presumably do not need to reorient attention following the cue because the target appears at the cued location. Of particular importance for the present study, this difference in RT is independent of the speed of response production, because the same choice responses (e.g., left and right button presses) are required regardless of cue validity. Therefore, this speeded test provides a measure of the time required for participants to voluntarily reorient attention. We predicted that individuals with MS would take significantly longer than healthy adults to voluntarily reorient attention.

Figure 8.

Experiment 3: cueing paradigm. Panel a depicts an example of a valid-cue trial, where a target letter (F or T), flanked by distractors, appears at the location cued by the rectangle. Panel b depicts an example of an invalid-cue trial, where a target letter appears at the location opposite that cued by the rectangle. 80% of trials contained valid cues, and 20% contained invalid cues.

Experiment 3

Method

Participants

Fourteen MS participants (12 females; 12 with relapsing-remitting MS and two with secondary-progressive MS; mean disease duration at test = 10.5 yrs, SE = 2.8 yrs; mean age = 42.4 yrs, SE = 3.1 yrs, range = 28 to 67 yrs; mean education = 15.5 yrs, SE = 0.5 yrs, range = 12 to 18 yrs) and 14 control participants (11 females; mean age = 41.5 yrs, SE = 3.9 yrs, range = 19 to 68 yrs; mean education = 16.5 yrs, SE = 0.6 yrs, range = 12 to 20 yrs) participated. There were no reliable differences in mean age or education level between groups. Twelve MS and 12 control participants also participated in Experiment 2. Recruitment and consent procedures, exclusion criteria, and payments were the same as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Apparatus and Stimuli

A desktop PC with an 18-inch CRT monitor was used for stimulus presentation and data collection. An eye tracker with an integrated chinrest (HiSpeed Eye Tracking Interface, SMI, Inc.) was used to monitor eye position and to maintain constant visual angles of stimuli across participants. Participants responded by pressing one of two keys labeled “F” or “T” on a keyboard. Custom MATLAB 7.3 code (The MathWorks, Inc.; Brainard, 1997) ensured precise timing of stimulus presentation and data collection. A white filled square (~0.2° visual angle) presented at the center of the screen against a black background served as a fixation point. White target letters (F, T) and irrelevant flanker letters (O) ~0.6° in width and ~1.1° in height were presented in Arial font. Target letters were presented ~9.1° from the vertical midline on the horizontal axis. A red rectangle, ~3.1° in width, ~2.4° in height, and ~0.3° in thickness, was centered ~9.1° from the vertical midline on the horizontal axis (i.e., surrounding the flanker stimuli), and served as a target-location cue.

Procedure

A schematic diagram of the task paradigm is presented in Figure 8. At the beginning of each trial, a fixation square appeared at the center of the screen along with three adjacent flanker stimuli in each half of the screen. 1520 ms later, a cue appeared surrounding the flanker stimuli either on the left or on the right side of the screen; the cue was equally likely to appear on the left as on the right. After a variable, blocked stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA: 53 ms or 1520 ms, alternating each trial block), a target letter (T in a random 50% of trials, F in the remaining trials) replaced the middle flanker stimulus on either the left or the right side of the screen and remained visible until a response was detected. The long SOA (1520 ms) was included to test whether group differences in cueing effects would be observed even when effects of the automatic capture of attention by the cue had dissipated prior to the onset of the target (i.e., cueing effects at this SOA reflect primarily voluntary, or endogenous, attention; Posner et al, 1982; Prinzmetal et al., 2005). A blank screen was presented during the 1-s inter-trial interval (ITI). In valid-cue trials, a target letter appeared only at the cued location (i.e., replacing the middle flanker stimulus surrounded by the cue); in invalid-cue trials, a target letter appeared only at the opposite location. A random 80% of trials contained valid cues and 20% of trials contained invalid cues. Participants were informed of these probabilities, and were instructed to attend covertly to the cued location. Participants were instructed to press the appropriate key as soon as they had identified the target letter, regardless of its location, and were told to be “as fast as possible while responding correctly.” In the case of an incorrect key-press, “Incorrect” appeared at the center of the screen for 2 s prior to the ITI. Participants were informed of their mean RT at the end of each trial block.

Participants were required to maintain fixation on the central square throughout the trial. If the participant broke fixation during the period from cue onset until a key-press response was detected, a feedback display was presented for 2 s prior to the subsequent ITI informing the participant that an eye movement had been detected, and a trial of the same type (i.e., combination of cue validity and SOA) was added to the end of the current trial-block queue.

Following written and oral instructions at the beginning of the session, participants were given two practice blocks, one for each SOA, each consisting of 10 trials with successfully maintained fixation. Participants then completed eight test blocks, each consisting of 50 trials with successfully maintained fixation.

Results

On average, individuals with MS failed to maintain fixation on 3.1% of trials and control participants failed to maintain fixation on 2.0% of the trials; this difference was not reliable (p = 0.20). There were no reliable interactions in the frequency of broken fixation involving cue validity, SOA, or participant group (ps > 0.05). For trials in which fixation was successfully maintained, there was no reliable difference in response accuracy between MS and control participants (95% CIMS: [0.83, 0.95], 95% CIControls: [0.85, 0.96], F(1,26) = 0.15, partial η2 < 0.01, p = 0.70), nor were there any interactions in accuracy involving participant group (smallest p = 0.45).

For correct responses, mean RTs are plotted in Figure 9a and mean cueing effects (RT for invalid-cue trials minus RT for valid-cue trials) are plotted in Figure 9b. Individuals with MS were slower to respond than were control participants (95% CIMS: [777, 1040 ms], 95% CIControls: [562, 825 ms], F(1,26) = 5.67, partial η2 = 0.18, p = 0.02). Pairwise t-tests indicated that both MS and control participants had reliable cueing effects for each of the short and long SOAs (largest p = 0.007). However, of particular interest, individuals with MS demonstrated mean cueing effects nearly twice the magnitude as those of control participants (95% CIMS: [90, 169 ms], 95% CIControls: [29, 107 ms]; group by cue-validity interaction: F(1,26) = 5.21, partial η2 = 0.17, p = 0.015, 1-tailed). There was no reliable interaction of participant group by cue validity by SOA (p = 0.99), indicating that SOA did not reliably affect the difference in cueing effect magnitude observed between MS and control participants.

Figure 9.

Experiment 3: Plotted in Panel a is mean (±SE) RT as a function of participant group, cue validity, and SOA. Plotted in Panel b is mean (±SE) cueing effect (a within-participant measure of mean RT for invalid-cue trials minus mean RT for valid-cue trials) as a function of participant group and SOA.

Discussion

Experiment 3 provides evidence for an attention-shifting deficit in MS: individuals with MS were abnormally slow to voluntarily reorient attention to target locations. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that insufficient allocation of attentional resources to target locations results in impoverished encoding of spatial representations in WM.

To our knowledge, only a few published studies (Gonzalez-Rosa, et al., 2006; Paul, Beatty, Schneider, Blanco, & Hames, 1998; Vazquez-Marrufo, et al., 2008; Vázquez-Marrufo, et al., 2009) have compared results from MS and control participants using an adaptation of Posner’s attention-cueing paradigm. Interestingly, in the subset of those studies that reported reliable group differences in cueing effect magnitudes (Gonzalez-Rosa, et al., 2006; Vazquez-Marrufo, et al., 2008), smaller cueing effects were found for MS than for control participants. In those experiments, a central arrow cue indicated with 80% validity the location (left or right of fixation) in which a single stimulus would appear. The target stimulus was a red and black checkerboard pattern, and the non-target stimulus was a white and black checkerboard pattern. If a target stimulus appeared, participants were required to press the left button if the target appeared on the left, and to press the right button if the target appeared on the right; participants were to refrain from responding if the non-target stimulus appeared instead.

Our finding of larger attention-cueing effects in individuals with MS is consistent with one interpretation of the seemingly paradoxical results of Gonzalez-Rosa et al. (2006) and Vazquez-Marrufo et al. (2008) that MS participants exhibited smaller cueing effects than did control participants. Both sets of results could be explained by intact attentional capture by salient peripheral cues but impairment in voluntary orienting of attention. In other words, cueing effects should be larger for individuals with MS than for control participants when the invalid cue captures attention at a peripheral location and participants must voluntarily reorient to the target location. In contrast, impaired voluntary orienting of attention should result in smaller cuing effects for MS than for control participants when the cue is presented centrally, providing only symbolic information regarding the peripheral location to be attended. In the latter case, individuals with MS may not have shifted, or maintained, attention to the cued location prior to target presentation. This would result in a relatively small RT difference between responses for validly and invalidly cued target locations. Furthermore, this pattern of results should be especially likely to occur when target detection or discrimination does not require highly focused attention, as was the case in previous studies (Gonzalez-Rosa, et al., 2006; Vazquez-Marrufo, et al., 2008; Vázquez-Marrufo, et al., 2009). By contrast, the current study presented a salient peripheral cue, and target stimuli that were difficult to discriminate without focused attention. Thus, the impaired voluntary allocation of attention (but preserved attentional capture) may manifest as seemingly contradictory patterns of results that depend on stimulus properties and other details of the task design. Additional work can be done to test this particular synthesis of existing results.

General Discussion

This study is one of the first detailed investigations of spatial WM in MS. It provides substantial evidence for MS-related spatial WM impairment, even for individuals with relapsing-remitting MS, which has typically been associated with less severe cognitive impairments relative to other progressive subtypes (e.g., Huijbregts et al., 2004; Schulz et al., 2006).3 Individuals with MS performed reliably worse than age-matched, healthy control participants on modified versions of the spatial span test. This finding was replicated in a second experiment, and was also observed for recognition as well as recall tests. The effect sizes were moderate but clearly evident at the group level. These results are impressive given the heterogeneity of the cognitive profile in MS: it is estimated that 35–50% of individuals with MS would not present with any cognitive impairment (Bobholz & Rao, 2003; Rao, Leo, Bernardin, & Unverzagt, 1991), and only a subset of the individuals with MS who do manifest cognitive impairment would be expected to have a WM deficit. Furthermore, even moderate impairments in WM ability may result in considerable decrements in complex cognition and performance. Therefore, we consider the current finding of spatial WM impairment to be significant and deserving of further investigation. It is important for researchers to conduct large-scale studies in the future to more precisely establish the prevalence of these impairments in the MS population. The current study is limited on this dimension both by the small number of participants and by the fact that clinical diagnosis was obtained in some participants by self-report according to their personal physicians, and so precise diagnostic criteria used was unclear in some cases where complete clinical records could not be obtained.

The main objective of the current study, however, was to localize, if possible, the spatial WM impairment in MS to deficits in specific cognitive or visuomotor processes. We eliminated several potential sources of the abnormally poor spatial span performance observed for individuals with MS: despite reliable effects of each of our manipulations within each participant group, there was no evidence for common MS-related deficits in spatiotemporal binding, maintenance (rehearsal), or memory retrieval. Furthermore, although visuomotor speed was positively correlated with spatial memory span for both participant groups, reduced speed of visuomotor processing alone could not account for the observed spatial WM impairment in individuals with MS (see also Parmenter et al., 2007), although it remains possible that WM impairments are related to a slowing of cognitive processing in general (e.g., DeLuca et al., 2004; cf. Lengenfelder et al., 2006).

Reasoning by elimination, we hypothesized an MS-related WM encoding deficit. Individuals with MS may be able to maintain and retrieve spatial information that has been adequately encoded into WM, whereas degraded encoding processes could limit the number and/or spatial precision (Walsh, Gmeindl, Marchette, Shelton, & Flombaum, 2011) of location representations available for maintenance and retrieval. Recent research suggests that the selective encoding into spatial WM of task-relevant (target) locations in the presence of task-irrelevant (non-target) locations requires the judicious allocation of visuospatial attention (Gmeindl et al., in press). As a result, a deficit in allocating visuospatial attention to target locations may underlie the spatial WM impairment in MS.

Results from Experiment 3 indicate that individuals with MS are abnormally slow to voluntarily reorient attention to target locations, a deficit that likely results in the impoverished encoding of spatial locations into WM. Like many results from neuropsychological studies, however, this finding is correlational in nature: individuals with MS have both spatial WM and voluntary attention deficits; verifying a causal relationship, however, requires further investigation. Furthermore, voluntary attention deficits may reflect (or contribute to) a general slowing of cognitive processing. Nevertheless, together with other research (e.g., Awh, Anllo-Vento, & Hillyard, 2000; Awh, Jonides, & Reuter-Lorenz, 1998; Awh et al., 1999; Gmeindl et al., in press; Jha, 2002; Munneke, Heslenfeld, & Theeuwes, 2010; Postle, Awh, Jonides, Smith, & D’Esposito, 2004; Smyth & Scholey, 1994), this study provides converging evidence regarding a close relationship between visuospatial attention and spatial WM.

We also observed an intriguing, unexpected result: whereas control participants performed worse when auditory distractors were introduced during target presentation in the spatial recall task, MS participants benefited from the presence of these “distractors;” in fact, individuals with MS performed as well as control participants in this condition. This finding, especially when considered in conjunction with the evidence for a voluntary attention deficit in MS revealed here, gives rise to the hypothesis that these auditory stimuli, which were unpredictable in location but time-locked to target presentation, served as cues for shifting attention to target locations. These stimuli may have provided alerting and/or pacing benefits that compensated for the slowed voluntary orienting of attention in MS, thereby improving the encoding of target locations into WM. Of potential relevance, auditory spatial stimuli provide both general alerting as well as cross-modal integration benefits for patients with hemispatial neglect performing visual search tasks (Van Vleet & Robertson, 2006). Furthermore, in what may be a related phenomenon, the gait patterns of Parkinson’s patients are improved when patients are provided with auditory metronome cues (Suteerawattananon et al., 2004). Therefore, pacing cues might similarly facilitate voluntary shifts of attention as well as overt acts of motor control. This possibility can be tested in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided to Leon Gmeindl by postdoctoral National Research Service Awards from the NEI (T32-EY07143) and the NIA (T32-AG027668), and to Susan Courtney by NIH grant R01 MH082957-01A2 and by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society through a Daniel Haughton Senior Faculty Award (SF1752-A-1) made possible by a grant from the Brodsky Family Foundation. We thank Chris Ackerman, Eunice Awuah, Sue Borchardt, Regina Brock-Simmons, Farai Chidavaenzi, Mike Esterman, Chase Figley, Josh Gootzeit, Deepti Harshavardhana, Ben Kallman, Derek Leben, and Caroline Montojo for assistance and/or helpful suggestions. We extend special thanks to the participants.

Footnotes

Moreover, doubts regarding the validity of the PASAT as a measure of working memory ability have been raised (see Fisk & Archibald, 2001).

Data from two control participants for the long-delay spatial condition were lost.

Individuals with secondary-progressive MS performed reliably worse in some conditions of Experiment 1 than those with relapsing-remitting MS. However, the former were reliably older, on average (52.2 yrs vs. 41.0 yrs, respectively), thus it is possible that these differences reflect effects of aging rather than disease subtype. Of note, after excluding participants with secondary-progressive MS the statistical pattern of results remained the same as that reported above.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/neu

References

- Amato MP, Ponziani G, Siracusa G, Sorbi S. Cognitive dysfunction in early-onset multiple sclerosis: A reappraisal after 10 years. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58:1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C, Onishi K, Robinson K, D’Esposito M, Thompson H, Rostami A, Grossman M. Serial position and temporal cue effects in multiple sclerosis: Two subtypes of defective memory mechanisms. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:853–862. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett PA, Higginson CI, Voss WD, Bender WI, Wurst JM, Tippin JM. Depression in multiple sclerosis: Relationship to working memory capacity. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(4):546–556. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett PA, Rao SM, Bernardin L, Grafman J, Yetkin FZ, Lobeck L. Relationship between frontal lobe lesions and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1994;44:420–425. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett PA, Rao SM, Grafman J, Bernardin L, Luchetta T, Binder JR, Lobeck L. Executive functions in multiple sclerosis: An analysis of temporal ordering, semantic encoding, and planning abilities. Neuropsychology. 1997;11(4):535–544. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awh E, Anllo-Vento L, Hillyard SA. The role of spatial selective attention in working memory for locations: evidence from event-related potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12(5):840–847. doi: 10.1162/089892900562444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awh E, Jonides J, Reuter-Lorenz PA. Rehearsal in spatial working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1998;24(3):780–790. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.24.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awh E, Jonides J, Smith EE, Buxton RB, Frank LR, Love T, Wong EC, Gmeindl L. Rehearsal in spatial working memory: evidence from neuroimaging. Psychological Science. 1999;10(5):433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Working memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4(11):417–423. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ. Working memory. In: Bower G, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. Vol. 8. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Monson N. Memory for temporal order in multiple sclerosis. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1991;29(1):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1996. Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH, Bakshi R, Simon JH, Priore R, Miller C, Munschauer F. Frontal cortex atrophy predicts cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2002;14:44–51. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berch DB, Krikorian R, Huha EM. The Corsi block-tapping task: methodological and theoretical considerations. Brain and Cognition. 1998;38:317–338. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1998.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergendal G, Fredrikson S, Almkvist O. Selective decline in information processing in subgroups of multiple sclerosis: An 8-year longitudinal study. European Neurology. 2007;57:193–202. doi: 10.1159/000099158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobholz JA, Rao SM. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2003;16:283–288. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000073928.19076.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor D, Duncan J, Lee ACH, Parr A, Owen AM. Frontal lobe involvement in spatial span: converging studies of normal and impaired function. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nature Protocols. 2006;1(5):2277–2281. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassington JC, Marsh NV. Neuropsychological aspects of multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology Review. 1998;8(2):43–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1025621700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase WG, Ericsson KA. Skill and working memory. In: Bower G, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 16. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1982. pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M. The MRC Psycholinguistic Database. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1981;33A:497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge FL, Middleton PA, Griego JA, Schmidt MM. The effects of interference on verbal learning in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1996;11(7):605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J, Berbieri-Berger S, Johnson SK. The nature of memory impairments in multiple sclerosis: Acquisition versus retrieval. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1994;16:183–189. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J, Chelune GJ, Tulsky DS, Lengenfelder J, Chiaravalloti ND. Is speed of processing or working memory the primary information processing deficit in multiple sclerosis? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26(4):550–562. doi: 10.1080/13803390490496641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito M, Onishi K, Thompson H, Robinson K, Armstrong C, Grossman M. Working memory impairments in multiple sclerosis: Evidence from a dual-task paradigm. Neuropsychology. 1996;10(1):51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk JD, Archibald CJ. Limitations of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test as a measure of working memory in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2001;7:363–372. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701733103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J, Rozewicz L, Davie CA, Thompson AJ, Miller DH, Ron MA. Correlates of executive function in multiple sclerosis: the use of magnetic resonance spectroscopy as an index of focal pathology. Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 1999;11(1):45–50. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J, Rozewicz L, Quaghebeur G, Davie CA, Kartsounis LD, Thompson AJ, Miller DH, Ron MA. Executive function in multiple sclerosis: The role of frontal lobe pathology. Brain. 1997;120:15–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forn C, Belenguer A, Parcet-Ibars MA, Ávila C. Information-processing speed is the primary deficit underlying the poor performance of multiple sclerosis patients in the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) Journal Of Clinical And Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;30(7):789–796. doi: 10.1080/13803390701779560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova HM, Sumowski JF, Chiaravalloti N, Voelbel GT, DeLuca J. Cognition in multiple sclerosis: a review of neuropsychological and fMRI research. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2009;14:1730–1744. doi: 10.2741/3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmeindl L, Walsh M, Courtney SM. Binding serial order to representations in working memory: A spatial/verbal dissociation. Memory & Cognition. 2011;39(1):37–46. doi: 10.3758/s13421-010-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmeindl L, Nelson JK, Wiggin T, Reuter-Lorenz PA. Configural representations in spatial working memory: Modulation by perceptual segregation and voluntary attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0180-0. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rosa JJ, Vazquez-Marrufo M, Vaquero E, Duque P, Borges M, Gamero MA, Gomez CM, Izquierdo G. Differential cognitive impairment for diverse forms of multiple sclerosis. BMC Neuroscience. 2006;7(39) doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby J, Ayarbe SD, Kravcisin N, Busenbark D. Working memory impairment among persons with chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 1994;241:125–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00868338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijbregts SCJ, Kalkers NF, de Sonneville LMJ, de Groot V, Reuling IEW, Polman CH. Differences in cognitive impairment of relapsing remitting, secondary, and primary progressive MS. Neurology. 2004;63(2):335–339. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129828.03714.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janculjak D, Mubrin Z, Brzovic Z, Brinar V, Barac B, Palic J, Spilich G. Changes in short-term memory processes in patients with multiple sclerosis. European Journal of Neurology. 1999;6(6):663–668. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.660663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AP. Tracking the time-course of attentional involvement in spatial working memory: an event-related potential investigation. Cognitive Brain Research. 2002;15(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J, Lewis RL, Nee DE, Lustig CA, Berman MG, Moore KS. The mind and brain of short-term memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:193–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler HR, Cohen RA, Lauer K, Kausch DF. The relationship between disability and memory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;62:17–34. doi: 10.3109/00207459108999754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, Francis WN. Computational Analysis of Present-Day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lengenfelder J, Bryant D, Diamond BJ, Kalmar JH, Moore NB, DeLuca J. Processing speed interacts with working memory efficiency in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvan I, Grafman J, Vendrell P, Martinez JM, Junque C, Vendrell JM, Barraquer-Bordas JL. Multiple memory deficits in patients with multiple sclerosis: Exploring the working memory system. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45:607–610. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520300025012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JE, Meyers KR. Rey Complex Figure Test and Recognition Trial. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Morgen K, Sammer G, Courtney SM, Wolters T, Melchior H, Blecker CR, Oschmann P, Kaps M, Vaitl D. Evidence for a direct association between cortical atrophy and cognitive impairment in relapsing–remitting MS. NeuroImage. 2006;30:891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munneke J, Heslenfeld DJ, Theeuwes J. Spatial working memory effects in early visual cortex. Brain and Cognition. 2010;72:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter BA, Shucard JL, Benedict RHB, Shucard DW. Working memory deficits in multiple sclerosis: Comparison between the n-back task and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12:677–687. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter BA, Shucard JL, Shucard DW. Information processing deficits in multiple sclerosis: A matter of complexity. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:417–423. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul RH, Beatty WW, Schneider R, Blanco C, Hames K. Impairments of attention in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 1998;4(5):433–439. doi: 10.1177/135245859800400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras MR, Magnano I, Canu EDG, Paulus KS, Satta WM, Soddu A, Conti M, Achene A, Solinas G, Aiello I. Longitudinal study of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: neuropsychological, neuroradiological, and neurophysiological findings. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry. 2003;74:878–885. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Cohen Y. Components of visual orienting. In: Bouma H, Bowhuis D, editors. Attention and Performance. Vol. 10. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1984. pp. 531–556. [Google Scholar]

- Postle BR, Awh E, Jonides J, Smith EE, D’Esposito M. The where and how of attention-based rehearsal in spatial working memory. Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;20:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinzmetal W, McCool C, Park S. Attention: Reaction time and accuracy reveal different mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2005;134(1):73–92. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Grafman J, DiGiulio D, Mittenberg W, Bernardin L, Leo GJ, Luchetta T, Unverzagt F. Memory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: Its relation to working memory, semantic encoding, and implicit learning. Neuropsychology. 1993;7(3):364–374. [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Hammeke TA, McQuillen MP, Khatri BO, Lloyd D. Memory disturbance in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 1984;41:625–631. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04210080033010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41:685–691. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Leo GJ, St Aubin-Faubert P. On the nature of memory disturbance in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1989;11(5):699–712. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchkin DS, Grafman J, Krauss GL, Johnson R, Jr, Canoune H, Ritter W. Event-related brain potential evidence for a verbal working-memory deficit in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1994;117:289–305. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L, Clark CM, Klonoff H, Li D, Paty D. Patterns of cognitive impairment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and their relationship to neuropathology on magnetic resonance images. Neuropsychology. 1996;10:176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz D, Kopp B, Kunkel A, Faiss JH. Cognition in the early stage of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 2006;253:1002–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin MS, Park SY, Park SR, Seol SH, Kwon JS. Clinical and empirical applications of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test. Nature Protocols. 2006;1(2):892–899. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]