Abstract

The present study examines the associations between coping efforts and psychological (internalizing and externalizing symptoms) and behavioral adjustment in a sample of 373 male juvenile offenders (ages 14-17) during the first month of incarceration. Social support seeking was associated with a more rapid decline in internalizing symptoms and lower levels of externalizing symptoms. Acceptance had a stress-buffering effect with regard to internalizing symptoms, whereas denial predicted higher levels of these symptoms. The only coping variable related to violent behavior was active coping, which was associated with lower rates of violent offending among youth with any violent incidents. The importance of fostering coping skills and increasing positive coping options for incarcerated adolescents is discussed.

Keywords: coping, delinquency, adolescence, internalizing, externalizing, institutional misconduct, juvenile offender

Adolescence is a period of life characterized by many novel stressors, including physical changes, school transitions, evolving relationships with friends and parents, involvement in romantic relationships, and difficult decision-making. Most youth are able to successfully navigate the challenges of adolescence, thanks in part to advancements in coping skills (Steinberg & Morris, 2001; Tolan & Henry, 1996), such as the ability to alter one's cognitions about a situation, generate multiple solutions to a problem, and recognize when and from whom to seek social support (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). Some youth, however, face the atypical and highly stressful experience of being incarcerated during adolescence. While a great deal of research has investigated how adolescents cope with other severe stressors, such as illness, medical procedures, and parental divorce [see Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, and Wadsworth (2001) for a review], only a handful of studies have examined how adolescents cope with imprisonment (Ashkar & Kenny, 2008; Brown & Ireland, 2006; Ireland, Boustead & Ireland, 2005). Given the importance of adolescence as a period for developing coping skills and the at-risk nature of youthful offenders, it is critical to improve our understanding of adolescents' efforts to cope while incarcerated. The present study investigates the impact of coping strategies on incarcerated adolescents' emotional and behavioral adjustment during the first month of incarceration in a high security juvenile facility.

Coping in an Incarceration Setting

Examining how the coping strategies used by incarcerated adolescents relate to their adjustment is an important empirical endeavor. Coping may be understood as the cognitive and behavioral strategies individuals employ in response to stress (Compas et al., 2001). To the extent that incarcerated youths' coping abilities contribute to conduct problems, these skills are central to youths' rehabilitation in general, and to the safety of facility staff and residents in particular. In addition, given the high rates of mental disorder—both internalizing and externalizing varieties—among delinquent youth (e.g., Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002), it is important to examine the degree to which youths' coping affects their emotional adjustment to incarceration, especially during the early stages of confinement, which may be particularly stressful (MacKenzie & Goodstein, 1985; Wormith, 1984).

One must consider several factors when studying coping in an incarceration setting. First, social interactions are primarily with other delinquent youth. This living situation may reduce the beneficial effects of social support seeking, especially for behavioral outcomes. In fact, research examining the effects of social interaction among at-risk youth finds that association with delinquent peers can lead to increases in antisocial behavior (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Poulin, Dishion, & Burraston, 2001). Also, one of the hallmarks of incarceration is reduced personal freedom, which limits options for self-distraction. For example, an incarcerated youth cannot decide to go for a walk to keep from worrying about a problem or turn on the television at will. Thus, incarceration may undermine the effectiveness of these coping strategies or even, in the case of social support seeking, invert its relation to adjustment.

Little prior research has directly examined the relations between coping and adjustment within an incarceration setting. One study that did so found that increased use of emotion-focused coping and avoidance were associated with poorer adjustment (a smaller reduction in depressive symptoms) over a six-week period (Brown & Ireland, 2006). Given that emotion-focused and avoidance coping tend to be maladaptive in the general population of adolescents (Compas et al., 2001), this finding suggests that some coping strategies may have similar effects inside and outside an incarceration context.

Goals of the Present Study

The present study builds on extant research in several ways. We focus on coping strategies that have been found to be salient for adolescents: active coping (thinking positively, planning and taking action), social support seeking (obtaining advice and comfort from others), self-distraction (engagement in activities unrelated to the stressor), and avoidance (denial of the stressor's reality) (Ayers, Sandler, West & Roosa, 1996; Gonzales, Tein, Sandler, & Friedman, 2001; Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Henry, Chung, & Hunt, 2002). Also, we take into account varying levels of stress, which is critical, as higher stress can lead to greater coping efforts as well as poorer adjustment (Compas et al., 2001). Finally, we build on Brown and Ireland's (2006) work by investigating interactions between stress and coping. Examining these interactions is useful because coping may operate as a buffer against stress and stress may interfere with adolescents' ability to cope (Gonzales et al., 2001; Wadsworth & Compas, 2002).

As noted previously, a preponderance of research suggests that higher levels of stress contribute to poorer adjustment (Compas et al., 2001). Therefore, we expect to find that those reporting greater stress will exhibit more internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as higher rates of violent behavior. Second, we hypothesize that active coping, which is generally found to be adaptive, will be associated with better adjustment. Though social support seeking and self-distraction are generally beneficial coping strategies for adolescents (Gonzales et al., 2001), it is unclear how these will relate to adjustment within the context of incarceration. We do, however, hypothesize that denial, an avoidance strategy, will be associated with poorer adjustment, just as it is for non-incarcerated adolescents (Compas et al., 2001; Gonzales et al., 2001) and adults (e.g., Carver, 1997). Finally, we hypothesize that some coping strategies will interact with stress in predicting adjustment to incarceration. Though we make no specific predictions about which strategies will interact with stress, we feel that the most convincing evidence of coping influencing adjustment is a finding of a stress-buffering effect.

Methods

Participants

Data for the current study were collected from interviews with 373 male juvenile offenders (ages 14-17, M = 16.421) incarcerated in the California Department of Juvenile Justice correctional reception facility. The sample was 29.0% African American, 53.1% Hispanic, 6.2% White, and 11.8% other- or mixed-race. This racial/ethnic composition is representative of the ethnic background of youth in the California juvenile justice system (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006). Most youth (69%) had committed a violent offense; the most common being robbery (23%), aggravated assault (17%), battery (6%) and attempted murder (6%).

Procedures

All youths between the ages of 14 and 17 years who were admitted to the facility for the first time or on a new offense were eligible for enrollment. Of youth approached, 95% assented to participate. Parental consent was obtained over the telephone in an audio-taped procedure. Of parents contacted, 97% provided consent. A baseline interview occurred within 48 hours of arrival to the facility, followed by interviews during the second, third and fourth week of incarceration. These were conducted in a private room by trained research assistants, who read the interview questions aloud to each participant and manually recorded his responses. Of the original 373 in the sample (all of whom completed the baseline interview), 95%, 95%, and 92% of youths completed the Week 2, Week 3, and Week 4 interviews. Reasons for missed interviews included participants' refusal, unavailability, and transfer out of the facility.

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Irvine and by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. A Certificate of Confidentiality was secured from the Department of Health and Human Services to ensure the confidentiality of information disclosed by participants.

Measures

Coping

Coping strategies were measured at the Week 4 interview with the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997). Youth were prompted to “[t]hink about the past month (since you arrived here) and how you have responded to the stress of being here.” The Brief COPE contains 28 items designed to tap 14 ways of coping with stress, eight of which--active coping, planning, positive reframing, seeking emotional support, seeking instrumental support, acceptance, denial, and self-distraction--were used to create the coping scales for the present study. For each item, participants rated on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (“I usually don't do this at all,”) to 4 (“I usually do this a lot”) how often they had engaged in the coping behavior described. Derived from the COPE scale, the Brief COPE yields a factor structure similar its parent scale (Carver, 1997), which has been used reliably with adolescent populations (e.g., Vaughn & Roesch, 2003).

We averaged the items assessing active coping, planning, and positive reframing to produce a single active coping scale (6 items, α = .88). We also averaged seeking instrumental support and seeking emotional support to create a social support seeking scale (4 items, α = .87). Self-distraction was used in its original, two-item form (α = .62). Denial (α = .77) and acceptance (α = .85), which were only weakly correlated, were analyzed as separate constructs.

Recent stress

To gauge participants' experiences of recent stressful life events, a 32-item scale adapted from the Adolescent Perceived Events Scale (Compas, Davis, Forsythe, & Wagner, 1987) was administered at Week 3. Participants indicated whether they had experienced any of the negative events described (e.g., “parents divorced/separated,” “lived in dangerous housing or neighborhood,” and “death of a friend”) in the past six months. A count of the items endorsed was calculated. Because the distribution was positively skewed (skewness = 1.05, SE = .13), the square root of the score (skewness = -.27) was used in the analyses.

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms

The 112-item Child Behavior Checklist - Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess internalizing and externalizing symptoms. T-scores for internalizing and externalizing (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) were used as dependent variables and time-varying covariates with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology. The scale was administered at each interview with a recall period of six months for the first interview and one week for the follow-up interviews.

Violent Offending

Official records of violent offending were obtained from the facility.

Plan of Analysis

To analyze the relations between use of coping strategies and the trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms during the first month of incarceration, we estimate latent growth curve models. In the model where internalizing symptoms are the dependent variable, externalizing is used as a time-varying covariate, and vice-versa2. Controlling for internalizing when examining effects of coping on externalizing symptoms and vice-versa, allows us to make inferences that are specific to internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, in spite of the co-morbidity of these types of symptoms (r = .4, p < .001). After establishing the shape of the trajectories, the independent variables (recent stress and coping strategies) and Stress X Coping interaction terms are added as predictors of the growth parameters.

Because the violent offending variable had a Poisson distribution featuring a preponderance of zeroes (47% committed no misconduct and 65% committed no violent misconduct), we conducted a logistic regression predicting any violent behavior then a Poisson regression predicting the count of violent incidents among those who had at least one. These analyses were run in a structural equation framework, which allowed us to account for correlations among the coping and recent stress variables.

For all models, p-values are reported based on either χ2difference tests (Δχ2) or log likelihood difference tests (Δ-2LL), comparing model fit between the original model and one where the parameter in question is set to zero. Models were estimated in MPLUS Version 5.21.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study variables, shown in Table 1, indicate that participants favored use of active coping, social support seeking, self-distraction and acceptance over denial.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Independent Variables.

| Mean | (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Active coping | 2.78 | 0.79 | -- | ||||

| 2. Social support | 2.32 | 0.89 | .49 | -- | |||

| 3. Self-distraction | 2.66 | 0.87 | .52 | .50 | -- | ||

| 4. Acceptance | 3.19 | 0.86 | .46 | 30 | .25 | -- | |

| 5. Denial | 1.60 | 0.83 | .11 | .16 | .17 | -.11 | -- |

| 6. Recent stress (sq. root) | 2.78 | 0.79 | .05 | .00 | -.02 | .13 | -.04 |

Note. Correlations that are underlined (but not bolded) are significant at p < .05. Those that are bolded (but not underlined) are significant at p < .01. Those that are bolded and underlined are significant at p < .001.

Internalizing Symptoms

We tested three models of the change over time in internalizing symptoms: no growth (latent intercept only), linear growth (latent intercept and slope terms), and quadratic growth (latent intercept, slope and quadratic terms). In each model, externalizing symptoms were entered as time-varying covariates (see Grimm, 2007). The models were specified such that the intercept was located at Week 4. The linear growth model was the most parsimonious. The model3 provided a good fit to the data [χ2(28) = 41.14, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, and RMSEA = .04 (90% CI = .00 to .06)]. Inspection of the growth parameters reveals that the intercept (at Week 4) for internalizing was 27.54 (SE = 1.34) and internalizing symptoms tended to decline over time at an average rate of 1.06 points (SE = .15) per week [Δχ2(1) = 49.66, p < .001].

The five coping variables were then entered into the model, along with recent stress, as predictors of the latent intercept and slope terms. Each independent variable was allowed to correlate with the others. In addition, each independent variable was allowed to correlate with externalizing, though these covariance estimates were constrained to be equal over time. The resulting model fit the data well [χ2(58) = 77.93, CFI = .98, TLI = .99, and RMSEA = .03 (90% CI = .01 to .05)]. This model explained 10% of the variability in the intercept and 9% of the variability in the slope of internalizing symptoms, with 7% and 8% of this variability being explained by the coping strategies (rather than by recent stress). The results (see Table 2) suggested that use of denial was associated with a higher level of internalizing [Δχ2(1) = 9.03, p < .01] and use of social support seeking was associated with a faster rate of decline in internalizing symptoms [Δχ2(1) = 6.02, p < .05]. The nature of this latter effect was such that, at baseline, use of social support seeking was associated with significantly increased levels of internalizing symptoms [Δχ2(1) = 6.74, p < .01]. However, by Week 4, these differences were no longer significant. Also, as expected, higher recent stress [Δχ2(1) = 9.76, p < .01] and externalizing symptoms [Δχ2(1) = 183.29, p < .001] were associated with elevated levels of internalizing symptoms.

Table 2. Regression of Latent Growth Parameters for Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms on Time-Invariant Covariates.

| Internalizing Symptomsa | Externalizing Symptomsb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Covariate | B | S.E. | 95% CI | Std. B | B | SE | 95% CI | Std. B |

| Intercept | Recent Stress | 1.62 | 0.51 | 0.61, 2.63 | 0.19** | 2.66 | 0.51 | 1.66, 3.65 | 0.30* |

| Active Coping | 0.39 | 0.78 | -1.15, 1.92 | 0.04 | -0.47 | 0.80 | -2.03, 1.09 | -0.05 | |

| Social Support | 0.24 | 0.65 | -1.03, 1.51 | 0.03 | -1.77 | 0.66 | -3.06, -0.49 | -0.20* | |

| Self Distraction | 1.15 | 0.67 | -0.17, 2.46 | 0.13 | 0.48 | 0.69 | -0.86, 1.82 | 0.05 | |

| Acceptance | -0.83 | 0.63 | -2.06, 0.40 | -0.09 | 0.78 | 0.64 | -0.47, 2.03 | 0.08 | |

| Denial | 1.77 | 0.58 | 0.63, 2.92 | 0.19** | 0.69 | 0.60 | -0.48, 1.86 | 0.07 | |

| Slope | Recent Stress | 0.19 | 0.15 | -0.12, 0.49 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | -0.17, 0.39 | 0.08 |

| Active Coping | 0.34 | 0.24 | -0.12, 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | -0.23, 0.63 | 0.12 | |

| Social Support | -0.48 | 0.20 | -0.87, -0.10 | -0.30* | 0.21 | 0.18 | -0.15, 0.56 | 0.14 | |

| Self Distraction | 0.23 | 0.20 | -0.17, 0.63 | 0.14 | -0.01 | 0.19 | -0.38, 0.37 | 0.00 | |

| Acceptance | -0.17 | 0.19 | -0.55, 0.20 | -0.11 | -0.17 | 0.18 | -0.51, 0.18 | -0.11 | |

| Denial | 0.05 | 0.18 | -0.30, 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.17 | -0.29, 0.36 | 0.02 | |

Note.

Controlling for the time-varying effects of externalizing symptoms.

Controlling for the time-varying effects of internalizing symptoms.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

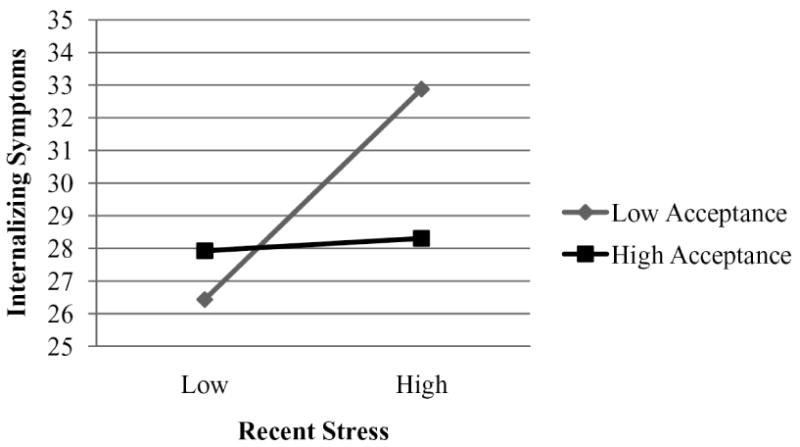

Our next step involved testing interaction terms of each coping variable and recent stress. Results indicated that acceptance [Δχ2(1) = 7.15, p < .01] significantly moderated the relation between recent stress and the level (intercept) of internalizing. This interaction term explained an additional 2.5% of the variation in the level of internalizing at Week 4. As illustrated in Figure 1, the nature of this interaction suggests a stress-buffering effect; among those using high levels of acceptance, the relation between stress and internalizing was attenuated.

Figure 1.

The stress-buffering effect of acceptance for internalizing symptoms at week 4 (controlling for externalizing symptoms and the effects of the other coping variables). “High” and “low” values are one SD above and below the mean for recent stress; and 4 (“A lot”) and 2 (“A little bit”) on the scale for use of acceptance because very few (4%) scored 1 on this scale.

Externalizing Symptoms

To examine the relations between coping and levels of externalizing symptoms (controlling for recent stress and internalizing symptoms), we followed the similar steps to those described in the previous section. A linear growth model was again the most parsimonious and best-fitting option. The model4 provided a good fit to the data [χ2(25) = 29.48, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .02 (90% CI = .00 to .05)]. The intercept (at Week 4) for externalizing was 33.58 (SE = 1.28) and the slope estimate was negative (B = -.60, SE = .19) and significantly different from zero [Δχ2(1) = 9.89, p < .01]. As seen with the internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms also declined across the first month of incarceration.

Recent stress and coping variables were then added to the model as predictors of the intercept and slope terms for externalizing. These explained an additional 4% of the variation in both intercept and slope (over the model including only recent stress). However, the only coping variable significantly associated with a growth parameter was social support seeking (see Table 2), which was associated with lower levels of externalizing [Δχ2(1) = 7.15, p < .01]. Also, recent stress [Δχ2(1) = 26.17, p < .001] and internalizing [Δχ2(2) = 277.56, p < .001] predicted greater externalizing. Testing of Coping X Recent Stress interaction terms revealed that none was significantly associated with the intercept or slope for externalizing symptoms.

Violent Offending

The logistic regression of violent offending on coping and recent stress revealed no significant associations (see Table 3). However, the Poisson regression uncovered a significant association between active coping and the count of violent incidents among those who had any such incidents (N=129) [Δ-2LL(1) = 4.77, p < .05]. Greater use of active coping was associated with a lower estimated count of violent incidents, controlling for recent stress and the other coping variables. We tested coping strategy X recent stress interaction terms (one at a time) in each model, but none was significantly related to either the dichotomous or count outcome.

Table 3. Logistic and Poisson Regressions of Violent Offending (Any and Count) on Coping Strategies and Recent Stress.

| Logistic regression (N=373) | eB | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Recent Stress | 1.10 | 0.95, 1.28 |

| Active Coping | 0.98 | 0.77, 1.25 |

| Social Support | 1.08 | 0.89, 1.32 |

| Self Distraction | 0.99 | 0.81, 1.22 |

| Acceptance | 0.96 | 0.79, 1.16 |

| Denial | 1.01 | 0.85, 1.19 |

| Intercept | 1.48 | 1.30, 1.70*** |

| Poisson regression (N=129) | eB | 95% CI |

| Recent Stress | 1.12 | 0.99, 1.26 |

| Active Coping | 0.75 | 0.56, 1.00* |

| Social Support | 1.14 | 0.98, 1.32 |

| Self Distraction | 1.00 | 0.86, 1.16 |

| Acceptance | 1.09 | 0.89, 1.35 |

| Denial | 1.04 | 0.92, 1.16 |

| Intercept | 1.42 | 1.30, 1.55*** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

The stress of incarceration would challenge the faculties even of those most adept at coping with adversity. Further, compared to adult prisoners, adolescent offenders face this situation with the added disadvantage of immaturity. Incarceration separates youth from their social networks at a time in development when youths' well-being (Helsen, Vollebergh, & Meeus, 2000) and acquisition of coping skills (Patterson & McCubbin, 1987) are still influenced heavily by family. Simultaneously, adolescents perceive their relationships with friends to be increasingly important (Helsen et al., 2000). Compounding the social isolation is the high rate of psychological disorder among adolescent offenders (Teplin et al., 2002), which may render them particularly vulnerable to the stresses of incarceration. Yet, research is only beginning to examine the types of strategies adolescent offenders employ to try to cope with incarceration or how their coping influences their adjustment while incarcerated. The present study finds that adolescent offenders do engage in efforts to cope and that they favor approach-oriented strategies, such as social support seeking and active coping techniques, as well as acceptance. However, these youths' coping efforts have only modest effects on adjustment within the first month of incarceration. Still, certain coping strategies appear to affect internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms and violent offending during the first month of incarceration.

Our first hypothesis was that youth who had experienced greater amounts of stress in the past few months would exhibit poorer adjustment within the incarceration facility. This hypothesis was partially confirmed. Recent stress was associated with higher levels of self-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms. It was not, however, significantly predictive of institutional reports of violent behavior. Our models did, however, produce positive estimated effects of recent stress on violent misconduct and, for the prediction of the number of violent incidents, the effect reached a trend level of significance. Thus, we feel it is likely that noise in the institutional reports of infractions (e.g., failure to detect all incidents and misattribution of some incidents) along with imprecision in our measure of stress led us to underestimate the true effect of stress on institutional behavior.

Our second set of hypotheses conjectured first that active coping would be associated with positive adjustment. Our findings do suggest that active coping may help militate against violent behavior while incarcerated, at least among youth with violent tendencies. However, this as well as the other coping effects, are rather small in magnitude, indicating low coping effectiveness. Active coping, though usually found to be beneficial (Compas et al., 2001), was not related to any of the other indicators of adjustment in this study. Still, this finding is somewhat promising, given that the youth reported fairly high levels of active coping, suggesting that they prefer this approach even if their coping efforts are not yet effective.

Regarding social support seeking, our findings are consistent with research identifying this as a key coping strategy used by adolescents (e.g., Ayers et al., 1996), as this proved a popular coping strategy. Our speculation that, in an incarceration context, social support seeking might have a negative effect on behavior appears to have been unfounded. As in other studies of adolescents (e.g., Seiffge-Krenke, 1993), social support seeking was associated with positive adjustment. However, it is important to note that use of this strategy was also predictive of higher levels of internalizing symptoms upon arrival to the institution. It may be that youth accustomed to turning to friends and family for support are more vulnerable to internalizing during the transition to incarceration, when they are removed from their usual sources of support. That social support seeking is associated with a reduction in internalizing symptoms over time indicates that this coping mechanism aids youth in adapting to the new environment. Overall, the findings suggest that seeking social support is beneficial for psychological well-being, even in a context where the most accessible sources of social support are other adolescent offenders.

However, the present data do not specify whom incarcerated youth turn to for social support. It is possible that support from different sources, such as facility staff, other inmates, family, or other visitors, have differential impacts on well-being and behavior. Considering the work of Dishion and colleagues (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Poulin, Dishion, & Burraston, 2001), which suggests that boys with behavior problems influence one another to adopt more antisocial attitudes and engage in further misconduct, it is unlikely that social support received from other inmates accounts for the beneficial effects of social support seeking, especially on externalizing symptoms. More likely, these adolescents are benefiting from social support received from family through phone calls and visits. Indeed, a recent study, based on the same sample as the present study, found that having visitors was associated with reduced symptoms of depression among these adolescents (Monahan, Goldweber, & Cauffman, in press). Investigation of the different sources of social support sought by incarcerated adolescents and their consequences for youths' adjustment is an important direction for future research.

Consistent with our hypotheses is the finding that denial, though less commonly endorsed by youth in the present sample, is associated with elevated levels of internalizing symptoms. This finding accords with the majority of research examining the correlates of denial (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000; Wadsworth & Compas, 2000). Furthermore, the finding reinforces the importance of distinguishing between truly avoidant strategies like denial and superficially avoidant strategies like self-distraction, which, though unrelated to adjustment, was strongly associated with active coping and social support seeking (Compas et al., 2001; Gonzales et al., 2001). Regarding self-distraction, no relations with adjustment were observed. While one cannot conclude from our study that self-distraction is truly unrelated to adjustment, the lack of associations with this coping variable is consistent with the idea that self-distraction may be a difficult technique to employ in an incarceration setting.

Thirdly, we predicted that some coping strategies would show evidence of stress-buffering effects, wherein youth using the strategies would experience fewer negative effects of stress. We found that one coping strategy, acceptance, appeared to operate in this way, shielding its users from internalizing symptoms, even if they had experienced high levels of recent stress. This finding suggests that some incarcerated youth are able to successfully employ what are known as secondary control coping strategies—those that require one to adjust one's internal state in order to adapt to a stressor (Band & Weisz, 1990). Given the largely uncontrollable nature of many of the stressors faced by incarcerated youth, it is promising to see some evidence of skill at secondary control coping in this population.

A finding that might be viewed as surprising is the average decline in symptoms of psychopathology over the course of the first month of incarceration. However, this pattern is consistent with other research examining psychosocial adjustment in the early stages of adolescents' incarceration (Brown & Ireland, 2006). The trajectory likely results from the increased stress associated with transitions and adaptation to a new (and possibly adverse) environment. Indeed, research on adult prisoners has long noted that the early phases of incarceration are especially stressful (MacKenzie & Goodstein, 1985; Wormith, 1984). Unfortunately, the present study cannot shed light on the course of these symptoms beyond the early stages of incarceration to determine whether and for how long they continue to decline.

While this study employed multi-informant assessments of adjustment and a longitudinal design, there are several limitations to consider. First, our method of assessing stress may not fully capture the variation in youths' perceived stress levels. Different youth may evaluate the same “stressful life events” (e.g., parents' divorce, failing grades, or a parent's arrest) as dissimilarly stressful. In addition, though all the youth were incarcerated, some may have appraised this experience as more stressful than others, and this difference would not necessarily be reflected in our stress variable. Future research assessing coping should attempt to assess stress with more comprehensive assessment tools. Finally, it is important to note that this study's findings may not generalize (a) to youth in other regions or countries, (b) to youth held in less secure facilities, (c) to less serious offenders, (d) to incarcerated girls, or (e) beyond the early stages of incarceration. Nevertheless, the present study provides important insight into the complex role that coping plays for adolescents adjusting to incarceration.

The most important conclusion to draw from this study is that incarcerated youth are not very effective at coping with the stresses that confront them. In spite of attempting to engage in coping efforts—especially those generally associated with positive adjustment—youth exhibited high levels of distress and misconduct during the first month of incarceration. Thus, aiding youth in improving their coping skills appears to be a worthwhile goal for practitioners working with this population. Clinicians might first assist youth in distinguishing between stressors that they can versus cannot (or should versus should not attempt to) change. Then, youth could be taught to employ acceptance and self-distraction to cope with uncontrollable stressors, such as other wards' provocative behavior or frustrating aspects of the incarceration facility's procedures. Surprisingly little research has examined the effectiveness of coping interventions on incarcerated youths' emotional and behavioral adjustment, though one recent study that evaluated a coping skills intervention specifically designed for incarcerated youth yielded promising results (Rohde, Jorgensen, Seeley, & Mace, 2004).

Unlike adult prisoners, adolescent offenders are at an age when separation from parents is not normative. Yet, many secure facilities limit residents' visitors and phone privileges, especially in the early stages of incarceration. In addition, some state and regional policies may result in youth being housed far from their families' homes, making visitation difficult. Policies that increase juvenile offenders' access to sources of social support, especially during the early stages of incarceration, could have positive effects on well-being and behavior (Monahan et al., in press). Furthermore, given adolescents' predilection for seeking social support, juvenile correctional institutions may promote rehabilitation by training their staff to be better sources of guidance and comfort for the adolescents in their care.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided to Elizabeth Cauffman, Ph.D. from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH01791-01A1) and from the Center for Evidence-Based Corrections at the University of California, Irvine. We are especially grateful to the many individuals whose cooperation and assistance made the data collection possible.

Footnotes

Age was not significantly correlated with any of the outcome variables in the study, nor was it associated with coping, except for a weak relation with self-distraction (r = .16, p < .01). Consequently, age was not included as a control variable in the analyses.

Testing of alternate models suggested that inclusion of the baseline scores in the growth curves (in spite of the longer recall period for that assessment) provided a better fit to the data than using the baseline scores as control variables.

The following constraints were placed on the model: paths regressing internalizing on externalizing were held constant over time, covariances between the growth parameters for internalizing and measures of externalizing were set to zero, residual variance estimates were held equal over time for externalizing, residual variance estimates were held equal over time except at baseline for internalizing, and covariance estimates for equally spaced measures of externalizing were set equal.

Model constraints included setting the residual variances to be equal over time for externalizing and internalizing symptoms; and setting the regression coefficients of externalizing on internalizing to be equal except at baseline.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth P. Shulman, University of California, Irvine, 4201 Social & Behavioral Sciences Gateway, Irvine, CA 92697-7085, eshulman@uci.edu

Elizabeth Cauffman, University of California, Irvine, 4201 Social & Behavioral Sciences Gateway, Irvine, CA 92697-7085, cauffman@uci.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar PJ, Kenny DT. Views from the inside. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2008;52:584–597. doi: 10.1177/0306624X08314181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, Roosa MW. A dispositional and situational assessment of children's coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band EB, Weisz JR. Developmental differences in primary and secondary control coping and adjustment to juvenile diabetes. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Ireland CA. Coping style and distress in newly incarcerated male adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping, but your protocol's too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Davis GE, Forsythe CJ, Wagner B. Assessment of major and daily stressful events during adolescence: The Adolescent Perceived Events Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;66:534–541. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Response to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary engagement stress response. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Tein J, Sandler IN, Friedman RJ. On the limits of coping: Interactions between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:372–395. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ. Multivariate longitudinal methods for studying developmental relationships between depression and academic achievement. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:328–339. [Google Scholar]

- Helsen M, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland JL, Boustead R, Ireland CA. Coping style and psychological health among adolescent prisoners: a study of young and juvenile offenders. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie DL, Goodstein L. Long-term incarceration impacts and characteristics of long-term offenders: An empirical analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1985;12:395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan KC, Goldweber A, Cauffman E. The effects of visitation on incarcerated juvenile offenders: How contact with the outside impacts adjustment on the inside. Law and Human Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10979-010-9220-x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, McCubbin HI. Adolescent coping style and behaviors: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescence. 1987;10:163–186. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(87)80086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, Dishion TJ, Burraston B. 3-year iatrogenic effects associated with aggregating high-risk adolescents in cognitive–behavioral preventive interventions. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Jorgensen JS, Seeley JR, Mace DE. Pilot evaluation of The Coping Course: A cognitive-behavioral intervention to enhance coping skills in incarcerated youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:669–676. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121068.29744.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I. Coping behavior in normal and clinical samples: More similarities than differences? Journal of Adolescence. 1993;16:285–304. doi: 10.1006/jado.1993.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:119–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 National Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry D, Chung K, Hunt M. The relation of patterns of coping if inner-city youth to psychopathology symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Henry D. Patterns of psychopathology among urban poor children: Comorbidity and aggression effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1094–1099. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn AA, Roesch SC. Psychological and physical health correlates of coping in minority adolescents. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:671–683. doi: 10.1177/13591053030086002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Compas BE. Coping with family conflict and economic strain: The adolescent perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Wormith JS. The controversy over the effects of long-term incarceration. Canadian Journal of Criminology. 1984;26:426–437. [Google Scholar]