Abstract

NOL7 is a putative tumor suppressor gene (TSG) localized to 6p23, a region with frequent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in a number of cancers, including cervical cancer (CC). We have previously demonstrated that reintroduction of NOL7 into CC cells alters the angiogenic phenotype and suppressed tumor growth in vivo by 95%. Therefore, to understand its mechanism of inactivation in CC, we investigated the genetic and epigenetic regulation of NOL7. NOL7 mRNA and protein levels were assessed in thirteen CC cell lines and twenty-three consecutive CC specimens by RTQ-PCR, western blotting, and IHC. Methylation of the NOL7 promoter was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing and mutations were identified through direct sequencing. A CpG island with multiple CpG dinucleotides spanned the 5′UTR and first exon of NOL7. However, bisulfite sequencing failed to identify persistent sites of methylation. Mutational sequencing revealed that 40% of the CC specimens and 31% of the CC cell lines harbored somatic mutations that may affect the in vivo function of NOL7. Endogenous NOL7 mRNA and protein expression in CC cell lines was significantly decreased in 46% of the CC cell lines. Finally, immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong NOL7 nucleolar staining in normal tissues that decreased with histologic progression towards CC. NOL7 is inactivated in CC in accordance with Knudson's two-hit hypothesis through LOH and mutation. Together with evidence of its in vivo tumor suppression, these data support the hypothesis that NOL7 is the legitimate TSG located on 6p23.

Keywords: NOL7, Hypermethylation, Mutation

Introduction

Cervical Cancer (CC) is the most common gynecological malignancy and third most common cancer among women worldwide (1). CC development is strongly associated with HPV infection. However, additional genetic alterations are required for malignant transformation (2-6). Therefore, the successful screening, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CC require further characterization of the key genetic alterations required for CC development. NOL7 is a putative TSG localized to 6p23, a region with frequent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in a number of cancers, including hormone-refractory breast carcinoma, leukemia, lymphoma, osteosarcoma, retinoblastoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and CC (7-25). Using CC as a model, where LOH of 6p23 is one of the most common allelic losses in this neoplasm (26-31), we demonstrated that NOL7 expression is regulated through genomic instability. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) experiments using BAC clones, as well as an 8-kb NOL7 genomic probe, demonstrated consistent loss of one NOL7 allele in CC cell lines as well as CC tumor samples (32). Reintroduction of NOL7 into CC cells with decreased NOL7 expression modulated the angiogenic phenotype, via decreased expression of the proangiogenic cytokine VEGF and increased expression of the anti-angiogenic factor TSP-1. Importantly, reintroduction of NOL7 suppressed tumor growth in vivo by 95% (32).

These studies suggest that NOL7 plays a significant role in the suppression of tumor growth. However, according to Knudson's two-hit hypothesis, inactivation of a TSG requires the functional loss of both alleles through various genetic or epigenetic mechanisms (33, 34). While numerous studies, including those within our own lab, have documented the LOH of 6p23 and NOL7, an additional hit has not been identified. In addition to the LOH, mutation and methylation represent two common methods of genetic and epigenetic inactivation (35, 36). A recent study identified mutations within NOL7 in 25% of the CC specimens examined. However, the limited number of samples investigated precludes definitive conclusions (37). Promoter methylation of genes localized to 6p is associated with cancer, and methylation of ID4 and POU2F3 has been reported on 6p23 (38, 39). However, no studies have specifically determined the methylation status of NOL7.

Materials and Methods

Identification of GC-rich Genomic Regions and CpG Islands

The EMBOSS-Isochore program was used to identify regions within the NOL7 gene that were GC-rich (40-42). The program was input with base pairs 13,614,790-13,621,437 of the Chr6 Genbank accession NC_000006.11. This identified a region from 13,614,790-13,616,240 that was subsequently analyzed for CpG islands using the EMBOSS-CpGPlot program (43, 44). Default settings for both programs were used (GC>0.5 and CpG>0.7 thresholds).

Cell Lines

All cell lines were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 in humidified incubators. Media and reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). HEK293T was used as a positive control for NOL7 expression. All media was supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin. Media was as follows: SiHa, Ca Ski, and ME180 - RPMI; HeLa and HEK293T - DMEM; AN3CA, C-33A, MS751, and CC-I – MEM; HEC-1-A and HT-3 - McCoy's; C-4I and C-4II - Waymouth's; SW756 - Leibovitz's. Genomic DNA from cell lines was extracted using the Gentra Puregene Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA from normal adult cervix was obtained from Biochain Institute Incorporated (Hayward, CA).

Tissue Specimens

CC tissue specimens were collected and used under the approval of the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Paraffin blocks of diagnosed cervical cancer specimens were obtained and representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) –stained sections were reviewed. Matched normal and cancer specimens were collected by laser capture microdissection (LCM) using the Leica AS LMD system. Genomic DNA from LCM sections was extracted as previously described (45).

Bisulfite Treatment and PCR Amplification

Genomic DNA from the cell lines, normal cervical mucosa and 23 CC samples was treated with sodium bisulfite as previously described (46). The bisulfite-treated DNA was used as template for PCR, using AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and primers region A (5’-GTGGTAGTAGGGTTGATTGG- 3’ and 5’-AATAAACCCCACTAAAAATACTCTAC-3’) and region B (5’-GTAGAGTATTTTTAGTGGGGTTTATT-3’ and 5’-AAACTACACCATAACCCA-3’). The PCR program used was 94°C for 10min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 59°C for 45s, 72°C for 45s and 72°C for 10min. The PCR products were resolved and visualized on a 1% agarose gel.

TOPO TA Cloning and Sequencing

PCR products from bisulfite-treated DNA extracted from cell lines and tissue samples were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector by TOPO TA cloning according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Ten colonies per transformation were sequenced using T7 and T3 primer sites within the pCR4-TOPO vector. Sequences were compared to the genomic template (accession number: NC_000006.11) and the CpGs were analyzed using MegAlign software (DNASTAR, Inc, Madison, WI).

Mutational Sequencing

Genomic DNA from cell lines and tissues was amplified by PCR using AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 5min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 20s, varied Tm for 30s, 72°C for 2min and 72°C for 10min. PCR products were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Cleanup System (Promega, Madison, WI) and sequenced using amplification primers. Sequences were compared to bases 13,614,022-13,621,437 of NC_000006.11 using MegAlign software (DNASTAR, Inc, Madison, WI) and ChromasLite (Technelysium Pty Ltd, Eden Prairie, MN). Potential biologic significance of the mutations was evaluated using Genomatix MatInspector (47), Human Splicing Finder (48), CRYP-SKIP (49-51), MicroInspector Prediction Software (52), and miRBase (53-57).

Real Time Quantitative PCR

Endogenous NOL7 mRNA expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR as described previously (58). Relative fold change for mRNA expression was quantified using the ΔΔCT relative quantification method and normalized to 293T mRNA levels. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described (58). Antibody conditions were as follows: NOL7, 12ng/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO); β-actin, 0.75ng/ml (Abcam, Cambridge MA); goat α-rabbit-HRP, 12.5ng/ml (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA). Results were quantified using Bio-Rad QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and normalized to β-actin.

Tissue Microarray and Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for NOL7 was performed on cervical tissue obtained with approval of the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. A tissue microarray (TMA) tissue microarray was generated using a Beecher Instruments ATA-27 Automated Tissue Arrayer. The TMA consisted of normal cervical mucosa (n=70), CIN I (n=22), CIN II (n=20), CIN III (n=23), and cervical squamous cell carcinoma (n=88). Deparaffinized sections were microwaved in ET buffer, α-NOL7 primary (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) was applied at 1:120 dilution for 1 hr at room temperature, and the rabbit EnVision+ kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, California, USA) was used for detection. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and scored on a 0-2+ scale, with 0 being the lowest staining and 2+ the greatest. Fisher's exact test was done for the comparison of NOL7 expression among the histologic groups. Unless otherwise stated, NOL7 expression was ranked as present (staining intensity 1 and 2) or absent (staining intensity 0) against Normal + CIN I vs. CIN II + CIN III + SCC groups.

Results

NOL7 is downregulated in CC cell lines and its expression decreases with progression in CC

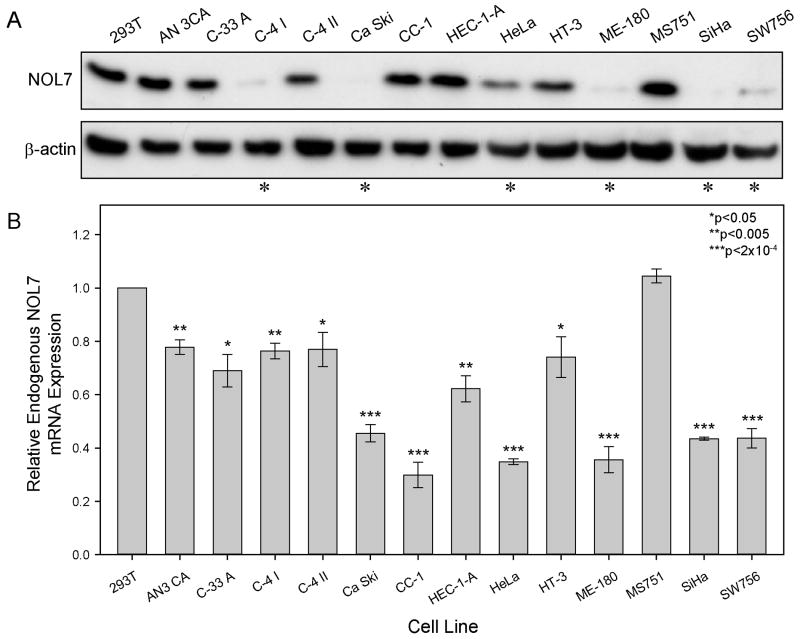

We have previously demonstrated decreased mRNA expression and allelic loss of NOL7 in a limited number of CC cell lines and tumor samples by Northern blot and FISH (32). To further characterize the expression of endogenous NOL7 in CC, we assessed mRNA and protein levels in an expanded set of CC cell lines. Using a polyclonal antibody against NOL7, we performed western blotting (Figure 1A) and compared this to mRNA levels as determined by real time quantitative PCR (Figure 1B), normalized to 293T cells which previous analyses indicated contain high levels of endogenous, normal NOL7. NOL7 protein expression was decreased by half in six of thirteen (46%) cell lines compared to 293T control (asterisk, Figure 1A). We also found that six of thirteen (46%) of CC cell lines demonstrate significantly decreased NOL7 mRNA expression (<50% of 293T control, p<2×10-4, Figure 1B). Four of these cell lines, Ca Ski, ME-180, SiHa, and SW756, demonstrate consistently downregulated NOL7 mRNA and protein. Interestingly, five of the thirteen (40%) cell lines, C-4 I, Ca Ski, CC-1, HEC-1-A, and HeLa, showed differential expression between NOL7 mRNA and protein levels, suggesting that NOL7 may also be posttranscriptionally and posttranslationally regulated.

Figure 1.

Analysis of Endogenous NOL7 Expression in CC Cell Lines. (A) Western blotting was performed on 25 μg whole cell lysate from a panel of CC cell lines. Expression was quantified in (B) using QuantityOne software from BioRad and normalized to β-actin. (B) Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from 13 CC cell lines and compared to 293T controls. Dashed line represents 50% of control expression.

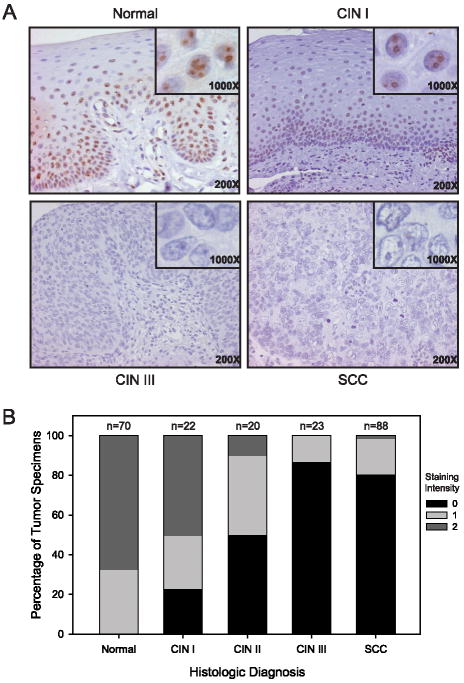

In order to assess endogenous NOL7 expression during the histologic progression of CC, IHC against NOL7 was performed on tissue microarrays (TMA) comprised of specimens from normal, CIN I, CIN II, CIN III, and SCC cervical tissue (Figure 2A). Tissues were scored 0, 1, or 2 based on staining intensity, with 0 being lowest and 2 being highest expressing. While the majority (95%) of normal and CIN I samples demonstrated staining for NOL7, less than 23% of samples from CIN II, III, and SCC had a staining intensity of 1 or 2 (p<0.001) (Figure 2B). Conversely, 77% of CIN II, III, and SCC tissues did not express endogenous NOL7, while only 5% of normal and CIN I tissues lacked NOL7 expression (p<0.001) (Figure 2B). These data suggest that NOL7 expression decreases significantly with histologic progression in CC, and that loss of NOL7 occurs after CIN I.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression of NOL7 in normal (A), CIN I (B), CIN III (C) and malignant cervical mucosa (D). Decreased nucleoplasmic NOL7 protein expression is observed with increasing histologic atypia. Original magnification 200x and 1000x. (E) Quantification of NOL7 expression in cervical mucosa. Normal (n=70), CIN I (n=22), CIN II (n=20), CIN III (n=23) and SCC (n=88). Data are expressed percentage of tumor specimens demonstrating an intensity of staining ranging from 0-2+.

CC cell lines and tumor samples do not have methylated NOL7 promoter

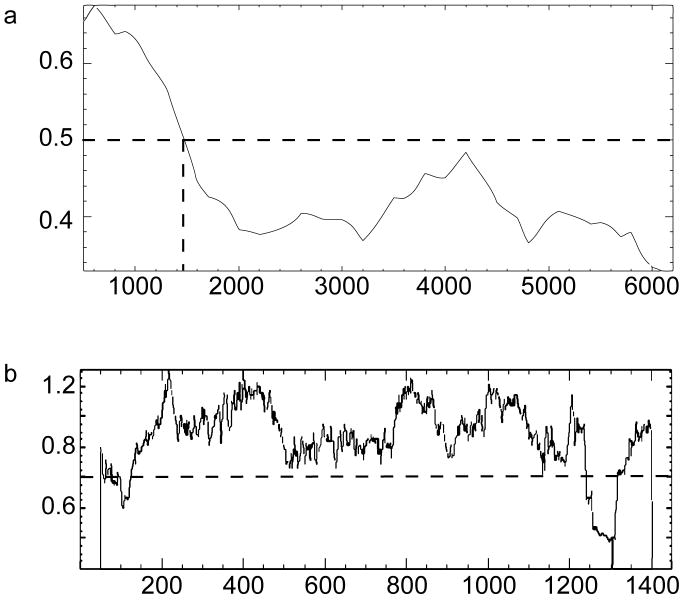

The significant loss of NOL7 expression in CC cell lines and cervical tissue suggests that NOL7 may function as a TSG. In accordance with Knudson's Two-Hit hypothesis, loss of the first allele of NOL7 by LOH must be followed by loss or silencing of the second allele through genetic or epigenetic mechanisms, likely methylation or mutation. Epigenetic regulation by methylation in a gene specific manner is dictated by the presence of a CpG island in the promoter of these genes (59). To determine if NOL7 might be regulated by this mechanism, the NOL7 genomic region was analyzed for high GC content that might indicate the presence of a CpG island. The region upstream of the NOL7 start codon averages greater than 60% GC across the region of interest (Figure 3A) (40-42). To determine if this GC rich region contained a CpG island, the genomic region sequence was analyzed using the EMBOSS CpG Plot program (44, 46). The analysis predicted a large CpG island about 1120 nucleotides in length, containing 111 CpG dinucleotides (Figures 3B).

Figure 3.

Prediction and Analysis of NOL7 Genomic Elements. (A) The genomic region of chromosome 6 (NC_000006.11) from bases 13,614,790 to 13,621,437 was analyzed using EMBOSS Isochore program to predict regions of high GC content. Dashed lines indicate the designated threshold of 0.5. (B) The 1,451 bp region of NOL7 that demonstrated a greater than 50% GC content was analyzed for the presence of a CpG island using EMBOSS CpGPlot. Dashed lines indicate a threshold of 0.7.

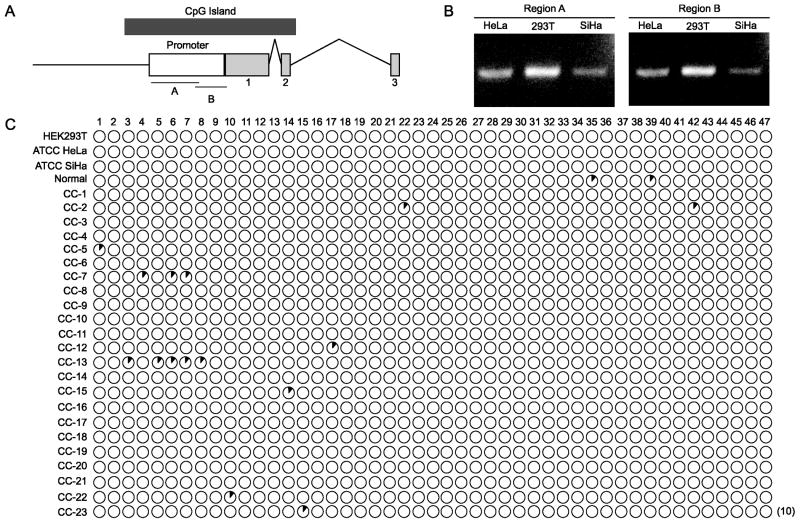

Promoter hypermethylation is a common mechanism by which many TSGs such as p16 and APC are silenced in CC (60). The promoter of NOL7 spans the 560 base pair region upstream of the start codon which contains 47 CpG dinucleotides (61). To specifically assess NOL7 promoter methylation, bisulfite PCR primers were designed such that the promoter region was split up in to two fragments; region A and B (Figure 4A). To assess the methylation status of NOL7 in cell lines that express a wide spectrum of endogenous NOL7, genomic DNA from 293T, HeLa and SiHa cell lines that express high, moderate, and low levels of endogenous NOL7 was bisulfite treated, PCR amplified, and TOPO TA cloned (Figure 4B). There was no methylation observed in the three cell lines (Figure 4C). To determine if the lack of methylation was an artifact due to cell culture, twenty-three consecutive cervical cancer tissue samples were analyzed and compared to normal cervix for methylation status. No significant methylation pattern was observed in either the normal or cervical cancer tissue samples (Figure 4C). These data suggest that methylation is not a mechanism of inactivation of the NOL7 gene.

Figure 4.

Bisulfite PCR-mediated Methylation Analysis. (A) Schematic of the NOL7 Genomic region with exons (light grey box), promoter region (white box) and CpG Island (dark grey box). Regions A and B indicate the bisulfite primer location. (B) Representative bisulfite PCR products for regions A and B from HEK293T, HeLa and SiHa cell lines. (C) Analysis of the methylation pattern of 47 individual CpG dinucleotides in the NOL7 promoter region. Ten clones were sequenced for the three cell lines, normal and 23 cervical cancer samples (CC-1 to 23) which is represented in parentheses. Open circles represent unmethylated CpG dinucleotides. Ten clones are represented per circle, with the methylated CpGs corresponding to the black shaded fraction.

NOL7 is mutated in CC

Lack of NOL7 methylation in the promoter region suggested that there may be inactivation through mutation. To determine if the genomic region of NOL7 harbors inactivating mutations, a series of primers were designed to cover the length of the NOL7 gene. Genomic DNA from cell lines (Table 1) and 23 consecutive matched normal and CC tumor specimens (Table 2) were collected and the NOL7 genomic region was sequenced. Four consistent variations from the genomic sequence of NOL7 were identified within the thirteen cell lines. Fifteen of the 23 samples showed variation from the NCBI reference sequence, and 40% of those represented somatic tumor-associated mutations. The majority of these mutations are clustered in intron 5 and the 3′UTR of NOL7. One mutation in intron 5 was identified in two of the tumor samples as well five of the thirteen cell lines examined (G13618408A). Using software prediction programs, the majority of the intronic mutations are within splicing regions that may influence alternative splicing of the NOL7 gene, while the 3′UTR mutations are associated with multiple miRNA sites (Tables 1 and 2). In addition to somatic, tumor-associated mutations, some cell lines and tumor samples also demonstrated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variations. In particular, SNP rs2841524 is located in the promoter region of NOL7. The variation at this locus was identified in 61% of CC cell lines and 39% of tumor samples. Variation of this particular allele from A→C is predicted to change the consensus HIF-1α binding element within the promoter. Taken together, this demonstrates that NOL7 harbors tumor-associated mutations and SNP variations, and suggests these genomic alterations may potentially contribute to NOL7 inactivation in conjunction with LOH.

Table 1.

Mutational analysis of NOL7 genomic region in CC cell lines. The results of direct mutational sequencing of the NOL7 genomic region within CC cell lines are listed. The location of the mutation corresponding to Genbank accession NC_000006.11 is listed, along with the region of NOL7 affected and frequency of the mutation within the 13 cell lines examined. The mutation, SNP status, and predicted effect are included.

| Variance | Genomic | NOL7 Region | Coding Change | SNP | Frequency | Predicted Biologic Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A → C | 13615401 | Promoter | rs2841524 | 61.54% | HIF1α binding site lost | |

| G → A | 13615702 | Exon 1 | G38R | - | 61.54% | May affect functionality of adjacent acidic domain |

| G → A | 13618408 | Intron 5 | - | 38.46% | Destroys splicing silencer motifs and creates new enhancer motifs; alternative splicing pattern | |

| T → C | 13620097 | Intron 5 | - | 7.69% | Destroys splicing silencer motifs and creates new enhancer motifs; alternative splicing pattern |

Table 2.

Mutational analysis of NOL7 genomic region in CC tumor samples. The results of direct mutational sequencing of the NOL7 genomic region in CC tumor samples are listed. The location of the mutation corresponding to Genbank accession NC_000006.11 is listed, along with the region of NOL7 affected. The mutation, SNP status, and predicted effect are included. The total mutation frequency is indicated.

| Variance | Genomic | NOL7 Region | SNP | Frequency | Predicted Biologic Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G → A | 13614430 | 5′UTR | - | 4.35% | Loss of hsa-miR-1225-3p, -145, -331-3p, -1274a, -500, and -326; Gain of hsa-miR-134 |

| A → C | 13615401 | Promoter | rs2841524 | 39.13% | HIF1α binding site lost |

| C → T | 13615444 | Promoter | - | 4.35% | AP-2 binding site lost |

| G → A | 13617979 | Intron 3 | - | 4.35% | Destroys splicing silencer and enhancer motifs; splice site broken |

| A → G | 13618177 | Intron 4 | - | 4.35% | Destroys splicing silencer motifs and creates new enhancer motifs; alternative splicing pattern |

| G → A | 13618408 | Intron 5 | - | 8.70% | Destroys splicing silencer motifs and creates new enhancer motifs; alternative splicing pattern |

| T → C | 13620207 | Intron 5 | - | 4.35% | Destroys splicing silencer and enhancer motifs; splice site broken |

| A → G | 13620386 | Intron 5 | - | 4.35% | Destroys splicing silencer and enhancer motifs; splice site broken |

| +AACT | 13621391 | 3′UTR | rs10695200 | 4.35% | Change in 3;UTR cis-elements |

| Deletion | 13621627 | 3′UTR | - | 4.35% | Loss of hsa-miR-19-1b and -182; Gain of hsa-miR-1184 |

| G → A | 13621698 | 3′UTR | - | 4.35% | Loss of hsa-miR-106b; Gain of hsa-miR-548m |

Discussion

HPV infection has a well-characterized role in the pathogenesis of CC (62-64). However, this event is insufficient for oncogenesis and the genetic and epigenetic changes that contribute to the development of CC are poorly understood. Chromosomal instability and LOH were among the first nonviral mechanisms identified that contribute to CC (26-29, 65). However, a limited number of putative TSGs, and their functional role in the development of CC, have been adequately described. One of the most common allelic losses in CC occurs at 6p23 (26-31). Within this chromosomal region there are several potential cancer-associated genes, including CD83 and NOL7. Evidence of genetic alterations of CD83 in CC has been demonstrated (37, 66). However, functional demonstration of its tumor suppressive capacity is lacking. Conversely, we have previously shown that NOL7 displays allelic loss in both CC cell lines and tumor samples. Furthermore, reintroduction of NOL7 into CC tumor cell lines suppresses in vivo tumor growth by 95% in part by the modulation of the angiogenic phenotype (32). In the current work, we investigated the genetic and epigenetic regulation of NOL7 and provide evidence of both mutations and LOH, further supporting the role of NOL7 as a TSG in CC.

CC development represents a continuum of cytologic and molecular alterations that takes place over decades. The interrogation of normal cervical mucosa, as well as various grades of CIN and CC demonstrated a decrease in the number of samples demonstrating NOL7 protein expression at the juncture between CIN I and CIN II (77.3% and 50.0%, Figure 2B). A further decrease was observed in CIN III (13%, Figure 2B) and vast majority of CC lacked NOL7 expression (19.3%, Figure 2B). This mirrors the progressive gain of expression of the angiogenic phenotype, as measured by the surrogate of microvessel density (MVD), during CC development (67-73). Interestingly, the dramatic loss of NOL7 expression in CIN III also correlates with the stable integration of the HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins (63, 74, 75). Therefore, decreased NOL7 expression concurrent with increased MVD and HPV integration supports the hypothesis that loss of NOL7 plays a critical role in the expression of the angiogenic phenotype during CC development and suggests that NOL7 expression may be additionally regulated through HPV oncoproteins. While it is currently unknown if there is a direct correlation between HPV type and NOL7 expression levels, the impact of HPV oncoproteins on upstream regulation of NOL7 is being investigated. It will also be of interest to determine if other cancers whose etiology is correlated with HPV infection, such as head and neck cancers, also demonstrate differential expression of NOL7 during histologic progression as has been observed in our CC model system.

Both global DNA hypomethylation and regional DNA hypermethylation have been observed in CC, suggesting methylation is likely a key mechanism for regulation of gene expression in CC (76). The identification of a CpG island within the promoter region of NOL7 suggested that the expression of the NOL7 gene might be epigenetically regulated. However, no methylation was detected in cell lines or tumor samples suggesting that methylation is not a mechanism of NOL7 regulation. In addition to the promoter region CpG island, an additional CpG island within the fifth intron of the NOL7 gene was detected. While nonpromoter methylation has been described in gene bodies and intergenic regions, their functional significance is not well understood (77, 78). Nonpromoter methylation can enhance transcription in a protein- and tissue-specific manner (79). Enhanced methylation in intergenic regions is also associated with splicing efficiency (80). A number of mutations were also detected in this region, suggesting that intron 5 may be an epigenetic hotspot that is targeted during CC development.

The mutations identified within intron 5 and other introns are predicted to affect splicing patterns of the flanking exons. Alternative splicing may account for up to 75% of the diversity in the human proteome and it is estimated that as much as 15% of the somatic mutations in cancer are attributable to alternative splicing (81, 82). These alternative splicing patterns can manifest as truncated, frameshifted, or unstable transcripts. Alternative or truncated protein products would likely demonstrate altered functionality in vivo, as critical localization domains of NOL7 are coded within the carboxy terminus of the protein (83). Aberrant splicing patterns can also negatively impact the stability and expression of mutant transcripts, triggering nonsense mediated decay (NMD) as well as other nuclear surveillance mechanisms (84-86). In addition, coupled splicing mechanisms can lead to altered cotranscriptional processing, leading to differential expression of an mRNA at multiple levels (87-89). Mutations within the 3′UTR of genes have also been shown to have significant effects on mRNA polyadenylation, stability, export, and subsequent translation (90-92). While the effect of the specific mutations on NOL7 expression and function cannot be determined from this work alone, the number of mutations within a small genomic locus suggests NOL7 may play a critical role in CC development and progression. It will be critical to experimentally determine the effect of these genetic alterations on NOL7 isoform expression, and assess their functional consequences in the context of the second NOL7 allele. In addition, some of the identified nucleotide changes correlate with characterized SNPs NOL7. In particular, the expression of the A versus C allele identified in the promoter region of NOL7 corresponds to the consensus for a HIF-1α binding site. While the role of HIF-1α in NOL7 expression must be validated experimentally, this is particularly compelling when considered in conjunction with data showing that loss of NOL7 correlates with the onset of angiogenesis in CC clinical progression.

In conclusion, NOL7 is a putative TSG in CC and perhaps other malignancies with loss of 6p23. In this current work, we sought to characterize the expression of endogenous NOL7 in CC and identify the mechanism of inactivation of its other allele. NOL7 was found to be significantly downregulated in six of thirteen CC cell lines. Further, NOL7 protein expression decreased with histologic progression. Through bisulfite and mutational sequencing of CC cell lines and tumor samples, we demonstrated that NOL7 is not methylated, but contains numerous tumor-associated somatic mutations and potentially deleterious SNPs in CC cell lines and tissue specimens. This provides additional evidence for the role of NOL7 as a bona fide TSG in CC and suggests a mechanism by which NOL7 may contribute to the pathogenesis of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Primers Used for Mutational Sequencing. The primers used to amplify and sequence the NOL7 genomic region from cell lines and CC tumor samples are listed. The primers are organized as pairs corresponding to the region amplified. Each region contained approximately 100 base pairs up and downstream of the exon boundaries to include any mutations that might affect splicing. Alignment numbers correspond to Genbank accession NC_000006.11.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Illinois Department of Public Health Penny Severns Cancer Research Fund (MWL) and National Institutes for Health 5R01CA100750-07 (RS) and 5R01CA129501-03 (RS).

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 Mar-Apr;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narisawa-Saito M, Yoshimatsu Y, Ohno S, et al. An in vitro multistep carcinogenesis model for human cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2008 Jul 15;68(14):5699–5705. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branca M, Giorgi C, Ciotti M, et al. Down-regulated nucleoside diphosphate kinase nm23-H1 expression is unrelated to high-risk human papillomavirus but associated with progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and unfavourable prognosis in cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2006 Oct;59(10):1044–1051. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.033142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann AM, Backsch C, Schneider A, Durst M. HPV induced cervical carcinogenesis: molecular basis and vaccine development. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2002 Nov;124(11):511–524. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-39579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999 Sep;189(1):12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazo PA. The molecular genetics of cervical carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999 Aug;80(12):2008–2018. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lung ML, Choi CV, Kong H, et al. Microsatellite allelotyping of chinese nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2001 Jul-Aug;21(4B):3081–3084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao SK, Perng YP, Shen YC, Chung PJ, Chang YS, Wang CH. Chromosomal abnormalities of a new nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line (NPC-BM1) derived from a bone marrow metastatic lesion. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998 May;103(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutirangura A, Tanunyutthawongese C, Pornthanakasem W, et al. Genomic alterations in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: loss of heterozygosity and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(6):770–776. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim G, Karaskova J, Vukovic B, et al. Combined spectral karyotyping, multicolor banding, and microarray comparative genomic hybridization analysis provides a detailed characterization of complex structural chromosomal rearrangements associated with gene amplification in the osteosarcoma cell line MG-63. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004 Sep;153(2):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeshita A, Naito K, Shinjo K, et al. Deletion 6p23 and add(11)(p15) leading to NUP98 translocation in a case of therapy-related atypical chronic myelocytic leukemia transforming to acute myelocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004 Jul 1;152(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amare Kadam PS, Ghule P, Jose J, et al. Constitutional genomic instability, chromosome aberrations in tumor cells and retinoblastoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004 Apr 1;150(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan YS, Rizkalla K. Comprehensive cytogenetic analysis including multicolor spectral karyotyping and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization in lymphoma diagnosis. a summary of 154 cases. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003 May;143(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batanian JR, Cavalli LR, Aldosari NM, et al. Evaluation of paediatric osteosarcomas by classic cytogenetic and CGH analyses. Mol Pathol. 2002 Dec;55(6):389–393. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.6.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starostik P, Patzner J, Greiner A, et al. Gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of MALT type develop along 2 distinct pathogenetic pathways. Blood. 2002 Jan 1;99(1):3–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giagounidis AA, Hildebrandt B, Heinsch M, Germing U, Aivado M, Aul C. Acute basophilic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2001 Aug;67(2):72–76. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.t01-1-00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Achuthan R, Bell SM, Roberts P, et al. Genetic events during the transformation of a tamoxifen-sensitive human breast cancer cell line into a drug-resistant clone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001 Oct 15;130(2):166–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shao JY, Wang HY, Huang XM, et al. Genome-wide allelotype analysis of sporadic primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma from southern China. Int J Oncol. 2000 Dec;17(6):1267–1275. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Issa B, Brothman LJ, Hendricksen M, Button D, Brothman AR. Nonrandom rearrangements of 6p in malignant hematological disorders. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000 Aug;121(1):22–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakase K, Wakita Y, Minamikawa K, Yamaguchi T, Shiku H. Acute promyelocytic leukemia with del(6)(p23) Leuk Res. 2000 Jan;24(1):79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagai H, Kinoshita T, Suzuki H, Hatano S, Murate T, Saito H. Identification and mapping of novel tumor suppressor loci on 6p in diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999 Jul;25(3):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemani M, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Cohen D, Cann HM. Detection of triplet repeat sequences in yeast artificial chromosomes using oligonucleotide probes: application to the SCA1 region in 6p23. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;72(1):5–8. doi: 10.1159/000134150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadayel D, Calabrese G, Min T, et al. Molecular cytogenetics of chronic myeloid leukemia with atypical t(6;9) (p23;q34) translocation. Leukemia. 1995 Jun;9(6):981–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoyle CF, Sherrington P, Hayhoe FG. Translocation (3;6)(q21;p21) in acute myeloid leukemia with abnormal thrombopoiesis and basophilia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1988 Feb;30(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(88)90193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischman EW, Prigogina EL, Iljinskaja GW, et al. Chromosomal rearrangements with a common breakpoint at 6p23 in five cases of myeloid leukemia. Hum Genet. 1983;64(3):254–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00279404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra AB, Murty VV, Li RG, Pratap M, Luthra UK, Chaganti RS. Allelotype analysis of cervical carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994 Aug 15;54(16):4481–4487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kersemaekers AM, Kenter GG, Hermans J, Fleuren GJ, van de Vijver MJ. Allelic loss and prognosis in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Cancer. 1998 Aug 21;79(4):411–417. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980821)79:4<411::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huettner PC, Gerhard DS, Li L, et al. Loss of heterozygosity in clinical stage IB cervical carcinoma: relationship with clinical and histopathologic features. Hum Pathol. 1998 Apr;29(4):364–370. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rader JS, Gerhard DS, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III shows frequent allelic loss in 3p and 6p. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998 May;22(1):57–65. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199805)22:1<57::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rader JS, Li Y, Huettner PC, Xu Z, Gerhard DS. Cervical cancer suppressor gene is within 1 cM on 6p23. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000 Apr;27(4):373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullokandov MR, Kholodilov NG, Atkin NB, Burk RD, Johnson AB, Klinger HP. Genomic alterations in cervical carcinoma: losses of chromosome heterozygosity and human papilloma virus tumor status. Cancer Res. 1996 Jan 1;56(1):197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasina R, Pontier AL, Fekete MJ, et al. NOL7 is a nucleolar candidate tumor suppressor gene in cervical cancer that modulates the angiogenic phenotype. Oncogene. 2006 Jan 26;25(4):588–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Apr;68(4):820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knudson AG. Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001 Nov;1(2):157–162. doi: 10.1038/35101031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000 Jan 7;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene Silencing in Cancer in Association with Promoter Hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003 November 20;349(21):2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Borecki I, Nguyen L, et al. CD83 gene polymorphisms increase susceptibility to human invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2007 Dec 1;67(23):11202–11208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagiwara K, Nagai H, Li Y, Ohashi H, Hotta T, Saito H. Frequent DNA methylation but not mutation of the ID4 gene in malignant lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2007 Apr;47(1):15–18. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.47.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Huettner PC, Nguyen L, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and silencing of the POU2F3 gene in cervical cancer. Oncogene. 2006 Aug 31;25(39):5436–5445. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pesole G, Bernardi G, Saccone C. Isochore specificity of AUG initiator context of human genes. FEBS Lett. 1999 Dec 24;464(1-2):60–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernardi G. Isochores and the evolutionary genomics of vertebrates. Gene. 2000 Jan 4;241(1):3–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernardi G. The human genome: organization and evolutionary history. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987 Jul 20;196(2):261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000 Jun;16(6):276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanteti R, Yala S, Ferguson MK, Salgia R. MET, HGF, EGFR, and PXN gene copy number in lung cancer using DNA extracts from FFPE archival samples and prognostic significance. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2009;28(2):89–98. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v28.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark SJ, Harrison J, Paul CL, Frommer M. High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994 Aug 11;22(15):2990–2997. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, et al. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jul 1;21(13):2933–2942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 May;37(9):e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kralovicova J, Vorechovsky I. Global control of aberrant splice-site activation by auxiliary splicing sequences: evidence for a gradient in exon and intron definition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(19):6399–6413. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buratti E, Chivers M, Kralovicova J, et al. Aberrant 5′ splice sites in human disease genes: mutation pattern, nucleotide structure and comparison of computational tools that predict their utilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(13):4250–4263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vorechovsky I. Aberrant 3′ splice sites in human disease genes: mutation pattern, nucleotide structure and comparison of computational tools that predict their utilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(16):4630–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baev V, Daskalova E, Minkov I. Computational identification of novel microRNA homologs in the chimpanzee genome. Comput Biol Chem. 2009 Feb;33(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004 Jan 1;32(Database issue):D109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: the microRNA sequence database. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;342:129–138. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: microRNA sequences and annotation. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2010 Mar;Chapter 12:11–10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1209s29. Unit 12 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 Jan 1;34(Database issue):D140–144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 Jan;36(Database issue):D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mankame TP, Zhou G, Lingen MW. Identification and characterization of the human NOL7 gene promoter. Gene. 2010 May 15;456(1-2):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands - [']A rough guide'. FEBS Letters. 2009;583(11):1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong SM, Kim HS, Rha SH, Sidransky D. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Clin Cancer Res. 2001 Jul;7(7):1982–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mankame TP, Zhou G, Lingen MW. Identification and characterization of the human NOL7 gene promoter. Gene. May 15;456(1-2):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(5):342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woodman CBJ, Collins SI, Young LS. The natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issues. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doorbar J. Molecular biology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006 May;110(5):525–541. doi: 10.1042/CS20050369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore DH. Cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 May;107(5):1152–1161. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000215986.48590.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu KJ, Rader JS, Borecki I, Zhang Z, Hildesheim A. CD83 polymorphisms and cervical cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Aug;114(2):319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith-McCune KK, Weidner N. Demonstration and characterization of the angiogenic properties of cervical dysplasia. Cancer Res. 1994 Feb 1;54(3):800–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dellas A, Moch H, Schultheiss E, et al. Angiogenesis in cervical neoplasia: microvessel quantitation in precancerous lesions and invasive carcinomas with clinicopathological correlations. Gynecol Oncol. 1997 Oct;67(1):27–33. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davidson B, Goldberg I, Kopolovic J. Angiogenesis in uterine cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997 Oct;16(4):335–338. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199710000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JS, Kim HS, Jung JJ, Lee MC, Park CS. Angiogenesis, cell proliferation and apoptosis in progression of cervical neoplasia. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2002 Apr;24(2):103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ozalp S, Yalcin OT, Oner U, Tanir HM, Acikalin M, Sarac I. Microvessel density as a prognostic factor in preinvasive and invasive cervical lesions. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24(5):425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ravazoula P, Zolota V, Hatjicondi O, Sakellaropoulos G, Kourounis G, Maragoudakis ME. Assessment of angiogenesis in human cervical lesions. Anticancer Res. 1996 Nov-Dec;16(6B):3861–3864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Triratanachat S, Niruthisard S, Trivijitsilp P, Tresukosol D, Jarurak N. Angiogenesis in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and early-staged uterine cervical squamous cell carcinoma: clinical significance. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Mar-Apr;16(2):575–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hudelist G, Manavi M, Pischinger KI, et al. Physical state and expression of HPV DNA in benign and dysplastic cervical tissue: different levels of viral integration are correlated with lesion grade. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Mar;92(3):873–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li W, Wang W, Si M, et al. The physical state of HPV16 infection and its clinical significance in cancer precursor lesion and cervical carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008 Dec;134(12):1355–1361. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duenas-Gonzalez A, Lizano M, Candelaria M, Cetina L, Arce C, Cervera E. Epigenetics of cervical cancer. An overview and therapeutic perspectives. Molecular Cancer. 2005;4(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008 Jun;9(6):465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009 Nov 19;462(7271):315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu H, Coskun V, Tao J, et al. Dnmt3a-dependent nonpromoter DNA methylation facilitates transcription of neurogenic genes. Science. 2010 Jul 23;329(5990):444–448. doi: 10.1126/science.1190485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choi JK. Contrasting chromatin organization of CpG islands and exons in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2010 Jul 5;11(7):R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Skotheim RI, Nees M. Alternative splicing in cancer: noise, functional, or systematic? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(7-8):1432–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tazi J, Bakkour N, Stamm S. Alternative splicing and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Jan;1792(1):14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhou G, Doci CL, Lingen MW. Identification and functional analysis of NOL7 nuclear and nucleolar localization signals. BMC Cell Biol. 2010 Sep 27;11(1):74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gardner LB. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay regulation by cellular stress: implications for tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 2010 Mar;8(3):295–308. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McGlincy NJ, Smith CW. Alternative splicing resulting in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: what is the meaning of nonsense? Trends Biochem Sci. 2008 Aug;33(8):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roy SW, Irimia M. Intron mis-splicing: no alternative? Genome Biol. 2008;9(2):208. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hartmann B, Valcarcel J. Decrypting the genome's alternative messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009 Jun;21(3):377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Isken O, Maquat LE. Quality control of eukaryotic mRNA: safeguarding cells from abnormal mRNA function. Genes Dev. 2007 Aug 1;21(15):1833–1856. doi: 10.1101/gad.1566807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Scholzova E, Malik R, Sevcik J, Kleibl Z. RNA regulation and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 2007 Feb 8;246(1-2):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell. 2009 May;101(5):251–262. doi: 10.1042/BC20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen JM, Ferec C, Cooper DN. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3′ regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes I: general principles and overview. Hum Genet. 2006 Aug;120(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lopez de Silanes I, Quesada MP, Esteller M. Aberrant regulation of messenger RNA 3′-untranslated region in human cancer. Cell Oncol. 2007;29(1):1–17. doi: 10.1155/2007/586139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primers Used for Mutational Sequencing. The primers used to amplify and sequence the NOL7 genomic region from cell lines and CC tumor samples are listed. The primers are organized as pairs corresponding to the region amplified. Each region contained approximately 100 base pairs up and downstream of the exon boundaries to include any mutations that might affect splicing. Alignment numbers correspond to Genbank accession NC_000006.11.