Abstract

Background

Delays in treatment time are commonplace for patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction who must be transferred to another hospital for per-cutaneous coronary intervention. Experts have recommended that door-in to door-out (DIDO) time(ie, time from arrival at the first hospital to transfer from that hospital to the percutaneous coronary intervention hospital) should not exceed 30 minutes. We sought to describe national performance in DIDO time using a new measure developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Methods

We report national median DIDO time and examine associations with patient characteristics (age, sex, race, contraindication to fibrinolytic therapy, and arrival time) and hospital characteristics (number of beds, geographic region, location [rural or urban], and number of cases reported) using a mixed effects multivariable model.

Results

Among 13 776 included patients from 1034 hospitals, only 1343 (9.7%) had a DIDO time within 30 minutes, and DIDO exceeded 90 minutes for 4267 patients (31.0%). Mean estimated times (95% CI) to transfer based on multivariable analysis were 8.9 (5.6-12.2) minutes longer for women, 9.1 (2.7-16.0) minutes longer for African Americans, 6.9 (1.6-11.9) minutes longer for patients with contraindication to fibrinolytic therapy, shorter for all age categories (except >75 years) relative to the category of 18 to 35 years, 15.3 (7.3-23.5) minutes longer for rural hospitals, and 14.4 (6.6-21.3) minutes longer for hospitals with 9 or fewer transfers vs 15 or more in 2009 (all P<.001).

Conclusion

Among patients presenting to emergency departments and requiring transfer to another facility for percutaneous coronary intervention, the DIDO time rarely met the recommended 30 minutes.

For patients arriving at an emergency department (ED) with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or left bundle branch block myocardial infarction, early treatment with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with significant improvement in outcomes, including mortality.1-3 With recent increased efforts to understand and reduce delays in treatment as captured by door-to-balloon (D2B) time, advances in knowledge about how to provide timely PCI,4 and implementation of national initiatives,5-7 a considerable reduction in D2B delays has been observed.8

The improvements in D2B times, however, reflect only the experience of patients who arrive directly at a hospital that provides primary PCI and exclude the ex perience of patients who are transferred to another hospital for PCI. A recent study9 indicates that patients who are transferred from one hospital to another for PCI experience long delays in PCI treatment. The primary PCI should be performed at least within 120 minutes, which would be no more than 90 minutes longer than the time required to deliver fibrinolytic therapy.10,11 A critical part of this process is the time spent in the referring hospital ED before transfer. Expert consensus, including the American Heart Association/ American College of Cardiology Performance Measures for STEMI,12 indicates that the door-in to door-out (DIDO) time, defined as the time from patient presentation to patient discharge from the transferring hospital, should be within 30 minutes.13,14 A DIDO time of longer than 30 minutes has been associated with a 56% odds increase in the risk of in-hospital mortality.15 However, little is known about how frequently this goal is met nationally. To address this issue, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a new performance measure that characterizes the DIDO time.16

Accordingly, we set out to examine national performance in DIDO time for patients with STEMI using data collected for the new performance measure by CMS about patients hospitalized in 2009. This measure is not restricted to Medicare patients. Also, we sought to determine the associations of DIDO time with patient and hospital characteristics and to report the percentage of patients who are transferred within 30 minutes13,14 and the percentage whose times exceeded 90 minutes. These findings can be critically useful for planning improvement efforts and monitoring quality. We also report DIDO time for each state.

METHODS

This is a retrospective observational study of CMS OP-3 (CMS Outpatient measure 3) measure, which is an assessment of the DIDO time for patients, in which we performed an analysis of DIDO times for patients who presented at an ED with STEMI and were transferred from the ED to another hospital for PCI.16 All patient-level data were reported by the ED hospital to CMS, and all information regarding ED hospitals was available from an existing CMS hospital database.

STUDY POPULATION

Our population is determined by CMS reporting requirements. In accord with the CMS Outpatient Prospective Payment System Final Rule17 of November 2007, hospitals were required to report data regarding hospital outpatient care in order to receive the full Outpatient Prospective Payment System payment rate, effective for payments beginning in calendar year 2009. For acute myocardial infarction outpatient care measures, hospitals were required to report data for patients at least 18 years of age who were evaluated in the ED with a primary diagnosis of STEMI (ST-segment elevation or left bundle branch block on the electrocardiogram closest to ED arrival). Hospitals submitted data to CMS quarterly and could choose to randomly sample patients, stratified by Medicare status, if the hospital had more than 80 outpatients with acute myocardial infarction in the quarter. Only outpatients who were transferred for primary PCI were included in the time-to-transfer measure. The complete reporting criteria are publicly available at the QualityNet Web site.16 We provide summary results on the set of all data submitted during 2009; all other analyses include data only on all patients reported by hospitals that submitted data regarding at least 5 eligible patients for the time-to-transfer measure from January 1 through December 31, 2009.

DATA MEASUREMENT

Outcome

Our outcome was DIDO time, measured at the patient level as the time from arrival in the ED to discharge from the same ED for patients who were transferred to another hospital for primary PCI. For hospitals and states, we summarized this as the median DIDO time for all patients transferred from that hospital or in that state.

Independent Variables

We assessed for patient age (18-35, 36-45, 46-55, 56-65, 66-75, and >75 y), sex, racial classification (white, African American, other, and unknown), time and date of arrival at the ED (7 am-5 pm weekdays vs off-shift), and whether any reason was given for not using fibrinolytic therapy (contraindication vs none); these data are reported to CMS by the ED hospital for each transferred patient. We also assessed hospitals by number of beds (1-99, 100-150, or >150), Census region, ownership (government owned, for profit, and nonprofit), location (rural or urban), and number of transfers reported (5-9, 10-14, or ≥15). Information about hospitals was taken from the Program Resource System, a national provider database maintained by CMS and the Quality Improvement Organizations.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We calculated median DIDO time and the interquartile range (IQR) in minutes for the overall patient population reported during the study period and then stratified by patient age, sex, race, contraindication, and arrival shift. We used a regression model to assess the association between these characteristics and DIDO time; because time in minutes was highly skewed, we used the natural logarithm of minutes as the dependent variable. For each characteristic, we reported the P value for the overall Wald test, testing the hypothesis that the associations for categorical variables constituting each characteristic were jointly equal to zero. We calculated the number and percentage of patients with a DIDO time of 30 minutes or less, and, to better assess the number of extreme delays in DIDO time, those with times longer than 90 minutes.

Because the CMS performance measure is median DIDO time for each hospital, we summarized the median DIDO time and its corresponding IQR of hospital median times for all hospitals, and then stratified by hospital bed size, ownership, geographic Census region, location (rural or urban), and number of eligible patients. We assessed the association of hospital characteristics with median time by estimating an ordinary least squares multivariable model for each characteristic, with median hospital time as the dependent variable.

To assess the independent association of patient and hospital characteristics with DIDO time, we estimated a mixed-effects model with natural logarithm of DIDO time as the dependent variable and the intercept specified as random across hospitals.18 This model included all patient and hospital characteristics described earlier. We used simulation to convert coefficients and standard errors to natural units19 and Wald tests to assess the joint significance of multiple category variables. For all patients included in the study, we calculated the median and IQR of DIDO times by US state for each state with at least 10 patients. We used an α of .05 to determine statistical significance. We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina) and STATA, version 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The total number of patients for whom data were submitted during the 12-month study period was 15 530 at 1841 hospitals; the median (IQR) DIDO time for this group was 66(45-110)minutes.Datafor1754ofthesepatients(11.3%) were submitted by hospitals that reported fewer than 5 patients; after excluding these patients, 13 776 patients at 1034 hospitals remained in the study sample, with hospital median (IQR) volume of 10 (7-17) patients. The median (IQR) DIDOtimeforthesepatientswas64(43-104)minutes;1343 (9.7%) were transferred within 30 minutes, and 4267 (31.0%) were transferred in longer than 90 minutes. DIDO time was longer for females, patients who were other than white, older patients, and patients with a contraindication to fibrinolytic therapy (all P<.001) (Table 1). Among patients with no contraindication, 75% had DIDO time longer than 43 minutes, and 25% had DIDO time longer than 110 minutes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Included in the DIDO Time Measure and Times for Those Patientsa

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Patients | DIDO Time, Median (IQR), min | Wald P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 13776 (100) | 64 (43-104) | |

| Age category, y | |||

| 18-35 | 278 (2.0) | 77 (50-125) | <.001 |

| 36-45 | 1310 (9.5) | 60 (42-94) | |

| 46-55 | 3300 (24.0) | 58 (40-87) | |

| 56-65 | 3629 (26.3) | 60 (42-96) | |

| 66-75 | 2689 (19.5) | 67 (45-111) | |

| >75 | 2570 (18.7) | 77 (50-136) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9355 (67.9) | 60 (41-95) | <.001 |

| Female | 4421 (32.1) | 73 (48-124) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 11 893 (86.3) | 63 (43-101) | <.001 |

| African American | 914 (6.6) | 71 (45-126) | |

| Other | 229 (1.7) | 72 (44-145) | |

| Unknown | 740 (5.4) | 67 (44-112) | |

| Contraindication | |||

| No | 10 428 (75.7) | 63 (43-101) | <.001 |

| Yes | 3348 (24.3) | 66 (45-114) | |

| Arrival time | |||

| Weekday 7 am to 5 pm | 5344 (38.8) | 64 (43-107) | .008 |

| Other | 8432 (61.2) | 64 (44-102) | |

| DIDO time, min | |||

| <30 | 1343 (9.7) | ... | |

| 30-90 | 8166 (59.3) | ... | |

| >90 | 4267 (31.0) | ... |

Abbreviations: DIDO, door-in to door-out; ellipses, not applicable; IQR, interquartile range.

Hospitals with 5 or more patients.

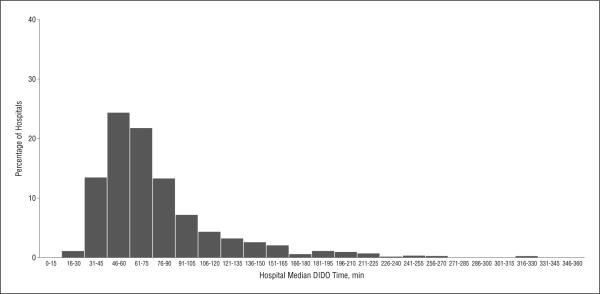

The median (IQR) hospital DIDO time among the 1034 hospitals reporting data for at least 5 patients for the 12-month period was 68 (52-91) minutes (Table 2 and Figure). Thirteen hospitals (1.3%) had median DIDO time of 30 minutes or less. In bivariate analyses, median times were significantly longer for hospitals that had less than 100 or more than 150 beds; were government owned; were rural; reported data for less than 10 cases; or were located in Mountain, West South Central, or Mid Atlantic geographic regions (all Wald P<.05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 1034 Hospitals Reporting 5 or More Patients for Inclusion in the DIDO Time Measure

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Hospitals | DIDO Time, Median (IQR), min | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| All hospitals Infrastructure | 1034 (100) | 68 (52-91) | |

| No. of beds | |||

| <100 | 430 (41.6) | 70 (53-98) | .04 |

| 100-150 | 239 (23.1) | 65 (50-90) | |

| >150 | 365 (35.3) | 68 (53-88) | |

| Ownership | |||

| Government | 195 (18.9) | 72 (53-109) | .002 |

| Private, not for profit | 689 (66.6) | 67 (52-89) | |

| Private, for profit | 150 (14.5) | 64 (51-93) | |

| Location | |||

| Urban | |||

| No | 420 (40.6) | 78 (58-113) | <.001 |

| Yes | 614 (59.4) | 63 (50-80) | |

| Geographic region | |||

| New England | 76 (7.4) | 66 (54-78) | <.001 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 137 (13.2) | 76 (60-96) | |

| East North Central | 220 (21.3) | 60 (48-75) | |

| West North Central | 79 (7.6) | 57 (44-79) | |

| South Atlantic | 203 (19.6) | 70 (52-96) | |

| East South Central | 104 (10.1) | 70 (53-101) | |

| West South Central | 81 (7.8) | 75 (55-107) | |

| Mountain | 41 (4.0) | 80 (54-132) | |

| Pacific | 93 (9.0) | 72 (53-113) | |

| Transfers | |||

| Annual No. of patients included in measure | |||

| 5-9 | 469 (45.4) | 77 (56-112) | <.001 |

| 10-14 | 234 (22.6) | 70 (53-92) | |

| ≥15 | 331 (32.0) | 59 (46-74) |

Abbreviations: DIDO, door-in to door-out; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure.

Distribution of median door-in to door-out (DIDO) times for 1034 hospitals reporting at least 5 patients in 2009.

Results of the multivariable model (Table 3) were similar to the bivariate results. After adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, women had a mean (95% CI) estimated time 8.9 (5.6-12.2) minutes longer than men; African Americans had an estimated time 9.1 (2.7-16.0) minutes longer relative to patients reported as white; patients aged 18 to 35 had an estimated time significantly longer than that for all except the group older than 75 years, with a time 18.3 (9.5-27.0) minutes longer relative to patients aged 46 to 55; and patients with contra-indications to fibrinolytic therapy had an estimated time 6.9 (1.6-11.9) minutes longer than those without contraindications (all P<.001). Among the hospital characteristics, rural hospitals had an estimated DIDO time 15.3 (7.3-23.5) minutes longer relative to urban hospitals, and hospitals in the East and West North Central regions had significantly shorter DIDO times than those in the New England region (all P<.001). Compared with hospitals that reported 5 to 9 patients, hospitals reporting 15 patients or more had a time 14.4 (6.6-21.3) minutes shorter. Compared with private for-profit hospitals, government-owned hospitals had an 8.1 (−2.9-18.2) minute delay. Bed size was not significant after controlling for the other variables in the model. Median DIDO varied across US states with at least 10 reported patients (Table 4), with the top-10 performing states having median times no greater than 52 minutes and the bottom 10 states having median times greater than 78 minutes.

Table 3.

Results of Mixed-Effect Model to Examine the Independent Association Between Patient and Hospital Characteristics and DIDO Time

| Variable | Estimated Effect, Mean (95% CI), min | P Value | Wald P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 87.0 (67.7 to 112.9) | <.001 | ... |

| Patient | |||

| Age category, y | |||

| 18-35 | 0 [Reference] | <.001 | |

| 36-45 | –14.7 (–23.5 to –5.0) | <.001 | |

| 46-55 | –18.3 (–27.0 to –9.5) | <.001 | |

| 56-65 | –15.2 (–24.3 to –5.6) | <.001 | |

| 66-75 | –10.6 (–19.7 to –0.2) | <.001 | |

| >75 | –3.3 (–13.4 to 7.9) | .24 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 0 [Reference] | ... | |

| Female | 8.9 (5.6 to 12.2) | <.001 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 0 [Reference] | <.001 | |

| African American | 9.1 (2.7 to 16.0) | <.001 | |

| Other | 3.3 (–8.4 to 17.4) | .33 | |

| Unknown | –0.5 (–8.1 to 6.9) | .78 | |

| Contraindication | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | ... | |

| Yes | 6.9 (1.6 to 11.9) | <.001 | |

| Arrival time | |||

| Weekday 7 am to 5 pm | 0 [Reference] | ... | |

| Other | 1.0 (–2.0 to 3.8) | .20 | |

| Hospital infrastructure | |||

| No. of beds | |||

| <100 | 0 [Reference] | .25 | |

| 100-150 | –0.1 (–8.3 to 10.7) | .97 | |

| >150 | 3.2 (-5.7 to 11.3) | .15 | |

| Ownership | |||

| Government | 0 [Reference] | .02 | |

| Private, not for profit | –4.1 (–15.6 to 4.5) | .10 | |

| Private, for profit | –8.1 (–18.2 to –2.9) | .006 | |

| Location | |||

| Rural | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | ... | |

| Yes | 15.3 (7.3 to 23.5) | <.001 | |

| Geographic region | |||

| NewEngland | 0 [Reference] | <.001 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 9.3 (–8.1 to 27.7) | .02 | |

| East North Central | –11.6 (–22.8 to 2.4) | .001 | |

| West North Central | –15.2 (–32.9 to –0.2) | <.001 | |

| South Atlantic | –1.7 (–13.8 to 15.7) | .64 | |

| East South Central | –1.7 (–16.5 to 15.7) | .67 | |

| West South Central | 7.1 (–10.5 to 28.1) | .13 | |

| Mountain | 1.8 (–15.0 to 31.1) | .77 | |

| Pacific | 2.0 (–12.8 to 19.9) | .66 | |

| Transfers | |||

| Annual No. of patients included in measure | |||

| 5-9 | 0 [Reference] | <.001 | |

| 10-14 | –2.5 (–10.3 to 5.6) | .26 | |

| ≥15 | –14.4 (–21.3 to –6.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: DIDO, door-in to door-out; ellipses, not applicable.

Table 4.

DIDO Time for Patients in US States, in Order of Increasing Times, for States With at Least 10 Reported Patients

| State | No. of Patientsa | DIDO Time, Median (IQR), min |

|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | 62 | 43 (31-73) |

| Kansas | 54 | 45 (33-67) |

| Minnesota | 439 | 49 (34-71) |

| Utah | 62 | 50 (34-108) |

| North Carolina | 829 | 50 (32-80) |

| Oregon | 182 | 50 (35-81) |

| Arizona | 196 | 51 (33-76) |

| Washington | 251 | 51 (33-78) |

| Indiana | 601 | 52 (35-80) |

| Maine | 97 | 52 (33-79) |

| Wisconsin | 394 | 55 (37-82) |

| Colorado | 56 | 57 (36-113) |

| Michigan | 568 | 58 (38-93) |

| Arkansas | 67 | 58 (45-115) |

| Illinois | 423 | 60 (42-88) |

| Vermont | 54 | 61 (32-112) |

| Alabama | 274 | 62 (41-105) |

| Nevada | 22 | 63 (50-89) |

| Ohio | 1197 | 63 (45-93) |

| Virginia | 407 | 63 (44-97) |

| Missouri | 318 | 64 (43-104) |

| All (nationwide) | 13776 | 64 (43-104) |

| Florida | 619 | 65 (45-105) |

| Massachusetts | 606 | 66 (45-100) |

| Rhode Island | 112 | 66 (48-110) |

| Iowa | 101 | 66 (50-92) |

| Georgia | 566 | 67 (47-113) |

| Kentucky | 298 | 67 (50-113) |

| Tennessee | 475 | 67 (45-112) |

| Texas | 578 | 68 (45-120) |

| Pennsylvania | 959 | 69 (47-107) |

| South Carolina | 205 | 69 (53-99) |

| Connecticut | 312 | 72 (55-117) |

| Mississippi | 140 | 74 (46-144) |

| California | 602 | 75 (47-130) |

| Oklahoma | 117 | 77 (55-118) |

| New York | 815 | 79 (54-129) |

| Idaho | 19 | 81 (65-129) |

| New Jersey | 241 | 82 (58-119) |

| District of Columbia | 14 | 92 (58-134) |

| Louisiana | 91 | 100 (62-175) |

| Montana | 18 | 103 (80-190) |

| New Mexico | 81 | 108 (58-179) |

| West Virginia | 161 | 118 (69-187) |

| Hawaii | 43 | 160 (83-240) |

| Wyoming | 19 | 207 (112-258) |

Abbreviations: DIDO, door-in to door-out; IQR, interquartile range.

COMMENT

Timely primary PCI treatment for patients with STEMI who are admitted to hospitals without PCI capabilities requires, as a first step, rapid evaluation and transfer. In the first national assessment of performance in this critical phase of treatment, we find that median times are more than double the 30 minutes recommended by many experts, with DIDO times exceeding 1 hour for more than half of patients. Moreover, marked variability is observed in DIDO times by patient and hospital characteristics, including geographic location.

National publicly reported measures of D2B times have included only patients who present directly to a PCI hospital. This public reporting, along with advances in knowledge about how to provide timely care and national quality initiatives, has led to marked improvements in the timeliness of treatment.5,6,8,20,21 However, concerns are growing that patients who require transfer for primary PCI often have times that far exceed guideline-recommended standards.9,22,23 Given a median time of 66 minutes at the first hospital and an unknown transit time to a second hospital, the challenge to achieve overall D2B times of less than 90 minutes for transferred patients is clear. Nallamothu et al9 and Chakrabarti et al22 reported that the time from presentation at the first hospital to PCI at the second hospital for 96.8% of transferred patients exceeded 90 minutes on the basis of the experience of hospitals participating in national registries. Measurement of the total D2B time (from first hospital to second) is technically difficult because it requires data from 2 hospitals or relies on data reported from the receiving hospital, which may have limitations in assessing the DIDO time. We assessed this first phase with data directly collected from the transferring hospital to provide some insight into the quality of care at that hospital and the likelihood that rapid primary PCI can be accomplished. A previous study has shown that times longer than 30 minutes are associated with a much higher risk of inhospital mortality.15 Our analysis of the CMS data provides strong evidence for the need to improve this aspect of care based on a comprehensive national assessment.

Evidence exists that faster DIDO time can be achieved by effective statewide collaborative initiatives. The Reperfusion of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Carolina Emergency Departments initiative is an example of a successful program that began in North Carolina in 2007 with the intent to establish a statewide system for reperfusion to overcome systemic barriers.14,24 Strategies in this initiative to reduce door-to-transfer times include leaving patients “on the stretcher” while the transfer decision is made and eliminating intravenous drips for transfers.24 Participating North Carolina hospitals have reported improvements in times, and our study shows that their current performance is much better than that of the aggregate of the other states. A similar statewide initiative in Minnesota also may be reflected in the performance of that state.25

We show marked patterns of delays by age, sex, and race. Although these findings could result from differences in presentation or other clinical factors, we cannot exclude the possibility that quality of care varies by these patient characteristics. Previously, disparities by race in D2B times were shown.26 With improvements in the overall timeliness of care, this disparity has been considerably reduced, with the greatest improvements among racial minorities with the longest times.27 This experience provides hope that improvements in the DIDO time for all patients would close or eliminate this gap in quality by patient demographic characteristics.

Our findings suggest that many patients may have benefitted from fibrinolytic therapy at the transferring hospital rather than from transfer for primary PCI. More than 75% of patients had no evidence of contraindication; yet, most had times greater than 30 minutes and many had times greater than 90 minutes. According to the 3 recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association performance measures for STEMI,12 these patients may have had better outcomes if they had been treated with fibrinolytic therapy and subsequent PCI within 3 to 24 hours.

We found no significant transfer time difference associated with time of arrival (regular vs off-shift) at the hospital after adjusting for other patient characteristics. This finding was consistent with that of a previous examination of door-to-needle times28 a possible explanation is that the transfer process—patient evaluation, treatment decision, and transfer initiation—and the DIDO time are primarily or exclusively determined within the ED, which is typically staffed at a similar level 24 hours daily, even at smaller hospitals.

Hospital median times to transfer varied substantially, with one quarter of hospitals having median times of 52 minutes or less and one quarter of hospitals having median times of 91 minutes or longer. Differences in times by type and location of hospital also were notable. Hospitals with more beds or more eligible patients had shorter median times, which may reflect a volume outcome effect or a greater likelihood of institutional commitment to reducing transfer time. Hospitals that transfer many patients are more likely to have systems in place to more efficiently facilitate transfers compared with hospitals that transfer few patients. Rural hospitals may be limited by lack of transportation, with delays partially attributable to time spent waiting for helicopter arrival and greater distances to PCI hospitals. Regional differences are explained less easily, unless the greater travel distances in Western and Pacific regions create a greater sense of urgency among hospitals that transfer many patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, we are unable to evaluate many factors that can affect DIDO time. Thus, in this study we cannot explore further which patients are most likely to experience the longest times and which factors may enhance performance in the best hospitals. Moreover, there may be some legitimate patient-centered reasons for delays. However, we found that it was rare to achieve the transfer-out time within 30 minutes, suggesting that this is more of a systemic problem than one related to an issue of a subset of patients. Second, the focus is on DIDO time from the ED, and we do not address direct transfers or the role of prehospital electrocardiograms in triage or regionalization strategies.29-32 Third, the hospitals are providing data based on self-report of the times for patients transferred for an anticipated procedure. However, the data used herein are from submissions to CMS as required by the CMS Prospective Payment System. The current study makes use of data that are planned to be publicly available and therefore adhere to CMS standards for publicly reported data. Data are collected retrospectively, and it is mandated that hospitals use a measurement system endorsed by the Joint Commission. Determination of “transfer for PCI” is made according to the documentation in the patient medical record; although the referral hospital may not perform the PCI, it anticipates that the transfer takes place for that purpose. Fourth, we have no information regarding transit times or D2B time at the PCI hospital, nor do we have data regarding patient outcomes, and cannot link DIDO time directly to mortality or morbidity. Nevertheless, prior work has established the importance of timely reperfusion, and these delays undoubtedly contribute to longer total D2B times and worse outcomes.2 The strength of the study is the inclusion of a national group of 1841 hospitals and information drawn directly from the institutions that are transferring.

In conclusion, our analysis of the median DIDO time for patients with STEMI presenting to an ED and transferred to another hospital for PCI indicates that most patients are transferred after twice the recommended time, and that tremendous variability exists, not only between hospitals but also across patient demographic categories and geographic locations. DIDO time may be a key component of treatment delays in patients with STEMI who are transferred for PCI; improvement efforts should focus on understanding and reducing this delay.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was conducted under a federal government contract with the CMS (HHSM-500-2008-00025I, Task Order T0001). This work was supported by grant U01 HL105270-02 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Dr Krumholz).

Role of the Sponsor: The CMS staff fully participated in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and critical review of the manuscript. The CMS reviewed and approved the use of its data for this work and approved submission of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Ms Miller and Dr Nsa (Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality) had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. Study concept and design: Drye, Bernheim, Bradley, and Krumholz. Acquisition of data: Miller, Turkmani, Han, Krumholz. Analysis and interpretation of data: Herrin, Miller, Nsa, Ling, Rapp, Bratzler, Bradley, Nallamothu, and Ting. Drafting of the manuscript: Herrin and Krumholz. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Herrin, Turkmani, Nsa, Drye, Bernheim, Ling, Rapp, Han, Bratzler, Bradley, Nallamothu,Ting,andKrumholz.Statisticalanalysis:Herrin, Miller, and Nsa. Obtained funding: Drye, Ling, Rapp, Han, and Krumholz. Administrative, technical, and material support: Turkmani, Bernheim, Rapp, Han, and Bratzler. Study supervision: Han and Krumholz.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Krumholz reports that he chairs a Cardiac Scientific Advisory Board for UnitedHealth-care and that he is the recipient of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc, through Yale University.

Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Terkelsen CJ, Sørensen JT, Maeng M, et al. System delay and mortality among patients with STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2010;304(7):763–771. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nallamothu BK, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. Time to treatment in primary percu taneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1631–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra065985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Chen J, et al. National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Association of door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with ST elevation myocardial infarction: national cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1807. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1807. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2308–2320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krumholz HM, Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, et al. A campaign to improve the time-liness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Door-to-Balloon: An Alliance for Quality. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1(1):97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin J, et al. National efforts to improve door-to-balloon time results from the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(25):2423–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antman EM. Time is muscle: translation into practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(15):1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krumholz HM, Herrin J, Miller LE, et al. Improvements in door-to-balloon time in the United States, 2005 to 2010 [published online August 22, 2011]. Circulation. 2011;124(9):1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nallamothu BK, Bates ER, Herrin J, Wang Y, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. NRMI Investigators. Times to treatment in transfer patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI)-3/4 analysis. Circulation. 2005;111(6):761–767. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155258.44268.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, et al. DANAMI-2 Investigators. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120(22):2271–2306. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192663. [published correction appears in Circulation. 2010;121(12):e257]

- 12.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Bachelder BL, et al. American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Emergency Physicians; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Hospital Medicine. ACC/AHA 2008 performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Performance Measures for ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) Developed in Collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Emergency Physicians Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Hospital Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(24):2046–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.012. [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(5):637-639]

- 13.Jollis JG, Roettig ML, Aluko AO, et al. Reperfusion of Acute Myocardial Infarction in North Carolina Emergency Departments (RACE) Investigators. Implementation of a statewide system for coronary reperfusion for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2371–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.joc70124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry TD, Unger BT, Sharkey SW, et al. Design of a standardized system for transfer of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction for percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2005;150(3):373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang TY, Nallamothu BK, Krumholz HM, et al. Association of door-in to door-out time with reperfusion delays and outcomes among patients transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2540–2547. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [September 14, 2011];Population and sampling specifications: specifications manual for hospital outpatient department quality measures, v2.0c. (encounter dates 01/01/09 through 06/30/09). QualityNet Web site. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=27377.

- 17.Quarterly Provider Updates Downloadable File. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site.; [June 24, 2011]. http://www.cms.gov/quarterlyproviderupdates/downloads/cms1392fc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage Publications; Newberry Park, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.King G, Tomz M, Wittenburg J. Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. Am J Pol Sci. 2000;44(2):341–355. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs AK, Antman EM, Ellrodt G, et al. American Heart Association's Acute Myocardial Infarction Advisory Working Group. Recommendation to develop strategies to increase the number of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients with timely access to primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2006;113(17):2152–2163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services [June 24, 2011];Hospital Compare. US Department of Health and Human Services Web site. http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/.

- 22.Chakrabarti A, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Rumsfeld JS, Nallamothu BK. National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Time-to-reperfusion in patients undergoing inter-hospital transfer for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the U.S: an analysis of 2005 and 2006 data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(25):2442–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(2):210–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glickman SW, Granger CB, Ou FS, et al. Impact of a statewide ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction regionalization program on treatment times for women, minorities, and the elderly. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):514–521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.917112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ting HH, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, et al. Regional systems of care to optimize time-liness of reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol. Circulation. 2007;116(7):729–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in time to acute reperfusion therapy for patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1563–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis JP, Herrin J, Bratzler DW, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. Trends in race-based differences in door-to-balloon times. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(11):992–993. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2005;294(7):803–812. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Concannon TW, Kent DM, Normand S-L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction regionalization strategies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):506–513. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.908541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry TD, Gibson CM, Pinto DS. Moving toward improved care for the patient with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a mandate for systems of care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):441–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitta SR, Myers LA, Bjerke CM, White RD, Ting HH. Using prehospital electrocardiograms to improve door-to-balloon time for transferred patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a case of extreme performance. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(1):93–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.904219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickman SW, Lytle BL, Ou FS, et al. Care processes associated with quicker door-in-door-out times for patients with ST-elevation-myocardial infarction requiring transfer: results from a statewide regionalization program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(4):382–388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]