Abstract

Objective

This study assessed health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and treatment satisfaction in sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAPT) compared with optimal conventional therapy—multiple daily injection (MDI) therapy with self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG)—in adults and children with type 1 diabetes and children's caregivers. Patient acceptance of new therapies is essential to their adoption and effective use.

Research Design and Methods

STAR 3, a randomized 12-month clinical trial, compared SAPT with MDI+SMBG in 485 adult and pediatric patients. Within- and between-treatment arm changes in generic HRQOL, diabetes-specific HRQOL (fear of hypoglycemia), and treatment satisfaction were assessed (significance criterion P<0.01).

Results

In adults, children, and caregivers, there were no significant between-arm changes in generic HRQOL: SF-36 Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary scores in adults and the PedsQL Physical Health Summary and Psychosocial Health Summary scores in children or caregivers. Diabetes-specific HRQOL (Hypoglycemia Fear Survey Worry and Behavior subscale scores) improved more in SAPT than in MDI adults. Hypoglycemia Behavior scores improved more in SAPT caregivers. Key treatment satisfaction measures (Insulin Delivery System Rating Questionnaire measures of Convenience, Efficacy, and Overall Preference) improved more in SAPT adults, children, and caregivers (all P<0.001); all exceeded the criterion for minimal detectable difference.

Conclusions

In the first-ever large-scale study of SAPT compared with optimal conventional therapy, SAPT had significant advantages for hypoglycemia fear in adults and caregivers and for treatment satisfaction in adults, children, and caregivers.

Background

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial results made it clear that intensive insulin therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) could reduce microvascular and macrovascular complications.1,2 These benefits have increased interest in technologies that might facilitate intensive therapy without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia or weight gain.

Today these technologies have burgeoned, including smaller insulin pumps that are easier to program, can administer basal and bolus insulin with personalized profiles, and allow wireless transmission of glucose readings from a blood glucose monitor to the pump. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems also have been introduced. The most recent advance is the development of sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAPT) systems that integrate real-time CGM features with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion.

Some potential benefits of these new technologies for glucose control are clear. Insulin pump use (compared with multiple daily injections [MDI]) has been shown to lower glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) levels with decreased risk of severe hypoglycemia,3 and CGM use (compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose [SMBG]) was associated with lower A1C levels in patients ≥25 years old but not in younger patients.4 Recent studies have shown that SAPT is associated with decreased A1C levels, especially in those who used the sensors most consistently.5–8

The documented advantages of each separate advanced technology over its conventional comparator (pump therapy over MDI and CGM over SMBG) led to the Sensor-Augmented Pump Therapy for A1C Reduction 3 (STAR 3) trial. STAR 3 compared the combined advanced technology platform (SAPT) with optimal conventional therapy (MDI+SMBG) in a large population (n=485) of pump- and CGM-naive adults and children with T1DM for 1 year. The study found advantages for SAPT in A1C reduction in both age groups with no significant difference between treatment arms in the rate of severe hypoglycemia or in weight gain.7 These outcomes take on special meaning because STAR 3 was designed as a real-life trial—after 5 weeks of training and initiation for SAPT participants all participants received only routine diabetes care (quarterly physician visits) for the duration of the study.

To be widely used and provide general benefits, new technologies must meet four criteria. They must provide (a) clinical advantages, (b) without compromising safety, as demonstrated by the STAR 3 clinical outcomes. New technologies must also be (c) acceptable to patients, and (d) patients must be able and willing to pay for them, either out-of-pocket or through healthcare coverage.

Here we assess factors likely to affect patient acceptance of SAPT—health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and treatment satisfaction—in the STAR 3 trial. HRQOL is a critical outcome in its own right, and treatment satisfaction and treatment preference can influence clinical outcomes via their effect on treatment adherence.9 In earlier studies pump therapy was favored over MDI in perception of general health and quality of life3 and in treatment satisfaction and treatment preference.10,11 A 6-month trial study found little change in HRQOL when CGM was introduced.12 The only study assessing treatment satisfaction for SAPT compared with optimal conventional therapy (a small, 16-week randomized controlled trial), showed advantages for SAPT in perceived blood glucose control efficacy, diabetes worries and interpersonal hassles, and overall satisfaction/preference.13

The STAR 3 trial offers a unique opportunity to assess HRQOL and treatment satisfaction associated with SAPT compared with MDI+SMBG because the trial assessed a broad range of these outcomes, including generic and diabetes-specific HRQOL and treatment satisfaction, in a large population of pediatric patients and their caregivers, as well as adult patients, over 12 months. HRQOL and treatment satisfaction were assessed using validated questionnaires.

Subjects and Methods

Study participants

Patients were eligible if they had T1DM, were between the ages of 7 and 70 years, had received MDI that included a long-acting analog insulin during the previous 3 months, and had an A1C level between 7.4% and 9.5%, been under the care of the clinical site principal investigator or a referring physician for at least 6 months, access to a computer, and a history of testing blood glucose an average of four or more times per day for the previous 30 days. Patients were excluded if they had used an insulin pump within the previous 3 years, had at least two severe hypoglycemic events in the year before enrollment, had used a diabetes drug other than insulin during the previous 3 months, or were pregnant or intended to become pregnant. One self-selected caregiver for each pediatric patient (7–18 years of age) completed HRQOL and treatment satisfaction measures. All participants provided written informed consent.

Mean age on entry to the study was 41.3 (±12.3) years for adults and 12.2 (±3.1) years for children. Fifty-seven percent of adults and 56% of children were male. Ninety-two percent of adults and 89% of children were non-Hispanic white, 3% of adults and 4% of children were Hispanic, and the remainder identified their race/ethnicity as other. Mean duration of diabetes was 20.2 (±12.0) years for adults and 5.0 (±3.4) years for children. Mean body mass index was 27.9 (±5.0) kg/m2 in adults and 20.4 (±4.1) kg/m2 in children. Adults and children entered the study with a mean A1C of 8.3% (±0.5%). There were no statistically significant differences (P<0.05) between SAPT and injection therapy arms on any of these baseline characteristics.7

Treatments

Patients were randomly assigned to either SAPT or MDI therapy using a block design, stratified according to age group: adults (19–70 years of age) or children (7–18 years of age). A1C and blood glucose in the two study groups and sensor glucose values in the pump-therapy group were disclosed to investigators, caregivers, and patients in order to optimize A1C levels and to minimize the risk of severe hypoglycemia.

The SAPT group used the MiniMed Paradigm® REAL-Time System (Medtronic, Northridge, CA). Before randomization all patients and caregivers of pediatric patients received training in intensive diabetes management, including carbohydrate counting and the administration of correction doses of insulin. SAPT patients first initiated insulin-pump therapy (for 2 weeks) and then began using glucose sensors. Patients in the SAPT group completed online pump training and attended additional visits for pump and sensor training during the 5 weeks after randomization. The MDI therapy group used both insulin glargine (Lantus®, sanofi-aventis, Paris, France) and insulin aspart (NovoLog® or NovoRapid®, Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) under the guidance of the clinical site study investigator. MDI patients were supplied with insulin pens. Sensor glucose values were collected for 1-week periods at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year in both study groups. MDI group participants used a CGM device that collected but did not display values (Guardian® REAL-Time Clinical, Medtronic). All patients used diabetes-management software (CareLink™ Therapy Management System for Diabetes–Clinical, Medtronic).

After 5 weeks of training and initiation for SAPT participants, all patients were seen as they would in typical clinical practice (follow-up physician visits every 3 months) for a year after randomization. Glucose data were reviewed, A1C was measured, and adverse event data were collected at all follow-up visits. Communication with clinicians between visits was initiated at the discretion of the patient.

Outcomes

The primary end point of this study was the difference between treatment groups in change in A1C percentage from baseline to 1 year of treatment. Secondary efficacy end points included frequency of severe hypoglycemia in each treatment group. Primary and secondary outcomes of the STAR 3 trial have been reported elsewhere.7 In brief, mean A1C levels decreased from 8.3% at baseline to 7.5% in the SAPT arm compared with 8.1% in the injection therapy arm (P<0.001). The rate of severe hypoglycemia and weight gain in the SAPT arm did not differ significantly from that in the injection therapy arm.7

Tertiary end points included standardized assessments of generic and diabetes-specific HRQOL and insulin delivery system treatment satisfaction. The SF-36v2 is widely used to assess generic HRQOL in adults.14 The instrument generates a variety of measures, including two composite scores: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). PCS and MCS scores are norm-based with a mean of 50 and an SD of 10 in the normative population.

The PedsQL is a scale widely used to assess generic HRQOL in children and their caregivers.15 The PedsQL version 4.0 Generic Core generates several measures, including summary scores assessing physical functioning and psychosocial functioning. Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale from 4=“never a problem” to 0=“almost always a problem.” Items are reverse-scored and linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL. Scale scores were computed as the sum of the items divided by the number of items answered. Child self-report versions (for 8–12 years of age and for 13–18 years of age) and parent reports of the child's HRQOL were utilized in the current study. Caregivers reported on their perceptions of child physical and psychosocial functioning. Children who transitioned from 12 years of age to 13 years of age during the study transitioned from one PedsQL version to the other; those who transitioned from 18 years old to 19 years old completed the same version at all time points.

Diabetes-specific HRQOL was assessed using the Hypoglycemia Fear Scale-II (HFS-II). It includes two subscales: Hypoglycemia Worry (items describing anxiety-provoking aspects of hypoglycemia) and Hypoglycemia Behavior (items describing behaviors to avoid hypoglycemia). Responses are on a 5-point scale from 1=“never” to 5=“always.” The current study utilized the HFS-II versions for adult participants16 and versions with slightly different wording for pediatric patients17 and for the caregivers of pediatric patients.18

Treatment satisfaction was assessed using the Insulin Delivery System Rating Questionnaire (IDSRQ), which assesses multiple dimensions of treatment consequences, satisfaction, and preference.9 The IDSRQ includes nine measures (possible range of scores=0–100). Six of the measures (treatment Convenience [labeled satisfaction in the original IDSRQ validation study], treatment Problems, Interference with daily activities, blood glucose monitoring [BG] Burden, clinical Efficacy, and Overall Preference [which also represents overall satisfaction]) ask questions specific to the respondent's insulin delivery system. Three other measures (diabetes Worries, Social Burden, and psychological Well-being) ask more general questions, not specific to the respondent's insulin delivery system but that might be affected by one's insulin delivery system. Three key IDSRQ measures were identified—Convenience, Efficacy, and Overall Preference; these were chosen because the latter provides the summary assessment, and research has indicated that Convenience and Efficacy are the two main determinants of Overall Preference.9

The Interference, Worries, and Burden measures are scored so that lower scores indicate higher treatment satisfaction; all other IDSRQ measures are scored so that higher scores indicate higher treatment satisfaction. All subjects in the current study completed the IDSRQ, although a few items in the adult subject version were not included in the pediatric or pediatric caregiver version (e.g., items about issues while traveling or engaging in sexual activities; only three of the 11 psychological well-being items were included in the pediatric caregiver version).

Statistical methods

For all HRQOL and treatment satisfaction measures intent-to-treat analysis was used with last observation carried forward for all participants who completed at least one administration of a measure after treatment initiation. All measures were assessed at baseline, 26 weeks, 39 weeks, and end of study; the IDSRQ and HFS-II were also administered at 13 weeks. Each subject with a baseline and end of study value for a measure was included in the analysis of that measure. All comparisons of treatment arms used analysis of covariance with treatment arm as the between-subject factor and baseline value as the covariate. Significance of within-arm change used paired t tests. Within-arm effect size (ES) was calculated as the amount of change in baseline pooled SD units (i.e., within-arm mean change divided by pooled baseline SD). Between-arm ES was calculated as the difference between within-arm ES. Minimum detectable difference (MDD), a measure of the meaningfulness of behavioral outcomes, was defined as an ES greater than 0.5.19 We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, but to reduce the risk of Type II error and to focus on results most likely to be statistically and clinically meaningful we set the criterion for statistical significance at P<0.01 and focused on results where treatment arm differences exceeded the MDD.

Results

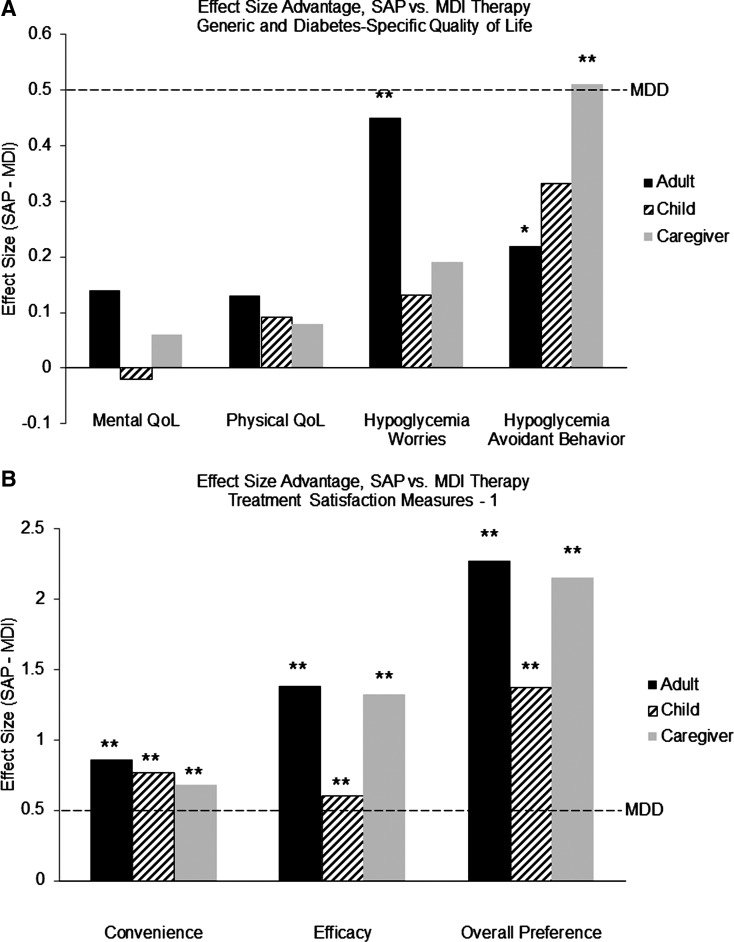

Baseline and 52-week change in HRQOL and treatment satisfaction for adults and pediatric patients and for children's caregivers appear in Table 1 and in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline and Change at End of Study Health-Related Quality of Life and Treatment Satisfaction for All Patients

| Adult | Pediatric | Caregiver | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | SAPT (n=166) | MDI (n=168) | Overall | SAPT (n=77) | MDI (n=70) | Overall | SAPT (n=77) | MDI (n=70) | Overall |

| SF-36 | |||||||||

| Mental Composite Score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 49.86 | 49.50 | |||||||

| Baseline SD | 9.64 | 9.09 | 9.35 | ||||||

| Week 52 Δ | 0.05 | [–1.26] | 1.31 | ||||||

| Physical Composite Score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 50.61 | 50.97 | |||||||

| Baseline SD | 7.12 | 7.86 | 7.51 | ||||||

| Week 52 Δ | 1.22 | 0.26 | 1.48 | ||||||

| Peds QL | |||||||||

| Psychosocial Health Summary Score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 78.38 | 78.76 | 78.61 | 73.27 | |||||

| Baseline SD | 14.59 | 10.27 | 14.04 | 12.87 | 13.36 | 13.84 | |||

| Week 52 Δ | 3.39 | 3.64* | −0.25 | 4.06 | 3.06 | 1.00 | |||

| Physical Health Summary Score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 86.99 | 88.37 | 87.92 | 85.53 | |||||

| Baseline SD | 12.93 | 11.16 | 12.09 | 10.58 | 13.06 | 11.85 | |||

| Week 52 Δ | 2.53 | 1.41 | 1.12 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.93 | |||

| Hypoglycemia Fear Survey | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia Worry | |||||||||

| Baseline | 21.96 | 21.52 | 28.88 | 26.97 | 42.49 | 43.21 | |||

| Baseline SD | 14.34 | 13.37 | 13.85 | 9.74 | 8.06 | 9.00 | 10.11 | 12.28 | 10.66 |

| Week 52 Δ | −6.36** | −1.87 | 4.49** | −3.62* | −2.43 | 1.19 | −3.64* | −1.56 | 2.08 |

| Hypoglycemia Avoidant Behavior | |||||||||

| Baseline | 16.38 | 16.70 | 30.60 | 29.70 | 31.65 | 30.94 | |||

| Baseline SD | 8.24 | 8.00 | 8.11 | 5.43 | 6.04 | 5.42 | 6.56 | 5.63 | 6.12 |

| Week 52 Δ | −2.30** | −0.52 | 1.78* | −4.01** | −2.25* | 1.76 | −4.16** | −1.07 | 3.09* |

| Insulin Delivery System Rating Questionnaire | |||||||||

| Convenience | |||||||||

| Baseline | 60.44 | 61.06 | 66.22 | 66.60 | 59.82 | 55.10 | |||

| Baseline SD | 20.75 | 21.48 | 21.09 | 21.51 | 18.29 | 19.95 | 21.00 | 18.68 | 19.99 |

| Week 52 Δ | 19.49** | 1.20 | 18.29** | 14.96** | [–1.66] | 16.62** | 16.97** | 3.35 | 13.62** |

| Problems (n) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 26.40 | 26.88 | 22.58 | 22.50 | 24.32 | 25.21 | |||

| Baseline SD | 15.30 | 13.84 | 14.56 | 13.90 | 14.57 | 14.17 | 11.81 | 12.97 | 12.35 |

| Week 52 Δ | −6.89** | −0.44 | 6.45** | [0.17] | −0.51 | −0.68 | −0.18 | [0.88] | 1.06 |

| Interference | |||||||||

| Baseline | 23.53 | 22.47 | 24.21 | 26.18 | 24.14 | 25.99 | |||

| Baseline SD | 18.87 | 18.21 | 18.52 | 21.77 | 23.51 | 22.57 | 16.20 | 19.12 | 17.62 |

| Week 52 Δ | −3.48 | 1.62 | 5.10* | −5.32 | −6.66 | −1.34 | −8.53** | −1.61 | 6.92* |

| BG Burden | |||||||||

| Baseline | 28.96 | 35.33 | 22.67 | 32.61 | 38.36 | 40.91 | |||

| Baseline SD | 33.68 | 36.12 | 35.03 | 36.11 | 36.20 | 36.37 | 30.64 | 34.98 | 32.68 |

| Week 52 Δ | −16.16** | −9.28* | 6.88** | −7.33 | −5.80 | 1.53 | −22.60** | −7.58 | 15.02** |

| Efficacy | |||||||||

| Baseline | 53.98 | 50.73 | 71.73 | 65.83 | 56.74 | 53.23 | |||

| Baseline SD | 20.24 | 22.13 | 21.24 | 23.24 | 30.99 | 27.35 | 20.63 | 18.58 | 19.68 |

| Week 52 Δ | 35.57** | 6.16* | 29.41** | 17.49** | 1.19 | 16.30** | 28.28** | 2.99 | 25.29** |

| Worries | n=75 | n=70 | n=73 | n=67 | |||||

| Baseline | 45.43 | 48.76 | 30.90 | 32.07 | 53.15 | 57.85 | |||

| Baseline SD | 18.18 | 17.14 | 17.72 | 20.19 | 20.86 | 20.45 | 13.76 | 15.08 | 14.55 |

| Week 52 Δ | −12.75** | −4.94** | 7.79** | −7.10** | −6.26 | 0.84 | −2.88 | −1.88 | 1.00 |

| Social Burden | |||||||||

| Baseline | 41.63 | 44.58 | 46.18 | 50.71 | 38.36 | 43.01 | |||

| Baseline SD | 17.30 | 16.69 | 17.04 | 23.70 | 24.07 | 23.91 | 20.13 | 22.89 | 21.56 |

| Week 52 Δ | −11.74** | −6.20** | 5.54 | −7.64 | −0.71 | 6.93 | −9.42** | −3.86 | 5.56 |

| Well-Being | |||||||||

| Baseline | 54.44 | 54.09 | 64.93 | 64.85 | 47.22 | 39.77 | |||

| Baseline SD | 14.61 | 14.69 | 14.63 | 11.81 | 13.27 | 12.50 | 17.13 | 16.28 | 17.08 |

| Week 52 Δ | 4.94** | 1.50 | 3.44* | 2.65 | 0.91 | 1.74 | 5.21* | [−1.29] | 6.50* |

| Overall Preference | |||||||||

| Baseline | 42.10 | 43.32 | 52.10 | 42.94 | 44.90 | 38.40 | |||

| Baseline SD | 13.88 | 15.74 | 14.84 | 22.44 | 19.00 | 21.26 | 14.66 | 17.43 | 16.33 |

| Week 52 Δ | 40.63** | 6.94** | 33.67** | 30.33** | 1.19 | 29.14** | 40.19** | 5.07 | 35.12** |

All scores indicate improvement except those with in brackets. Adult sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAPT), n=164–166 for all measures; Adult multiple daily injection therapy with self-monitoring of blood glucose (MDI), n=163–168 for all measures; Pediatric SAPT, n=72–77 for all measures (except Peds QL n=68); Pediatric MDI, n=69–70 for all measures (except Peds QL n=62); Caregiver SAPT, n=72–77 for all measures (except Peds QL n=63); Caregiver MDI, n=66–70 for all measures (except Peds QL n=55).

Significance for within-arm change was determined by within-subject t test; significance for between-group comparison of change was determined by analysis of covariance of change scores using treatment arm as between-subject factor and the baseline value as covariate. Positive values for Week 52 change (Week 52 Δ) indicate greater improvement in SAPT. *P<0.01, **P<0.001.

BG Burden, Blood Glucose Monitoring Burden; Overall Week 52 Δ, difference between SAPT and MDI Week 52 Δ.

FIG. 1.

Effect size advantage for sensor-augmented pump therapy (SAPT) versus multiple daily injections (MDI) therapy. *P<0.01, **P<0.001. MDD, minimal detectable difference. (A) Generic and diabetes-specific quality of life (QoL). Generic adult QoL was assessed using SF-36, whereas generic child and caregiver QoL was assessed using PedsQL. (B) Three key treatment satisfaction measures shown by the Insulin Delivery System Rating Questionnaire. (C) Additional treatment satisfaction measures shown by the Insulin Delivery System Rating Questionnaire.

Generic HRQOL (Table 1 and Fig. 1A)

There was no significant change among adults in either measure of generic HRQOL (SF-36 PCS or MCS scores) in either arm and no significant between-arm difference in change.

There was no significant change among children and caregivers in one measure of generic HRQOL (PedsQL Physical Health Summary scores) in either arm, with no between-arm difference in change. There was a significant improvement in the other measure of generic HRQOL (PedsQL Psychosocial Health Summary scores) only among children in the MDI arm; there were no significant between-arm differences in change.

Diabetes-specific HRQOL (Table 1 and Fig. 1A)

Both measures of hypoglycemia fear (hypoglycemia worries and hypoglycemia avoidant behavior) improved significantly during the study in all SAPT arm groups (adults, children, and caregivers). Only one measure of hypoglycemia fear (hypoglycemia avoidant behavior) improved significantly during the study in the MDI arm, and this improvement was observed only in children. Change in the SAPT arm was significantly greater than change in the MDI arm for adults (for both hypoglycemia worries and hypoglycemia avoidant behavior) and in caregivers (for hypoglycemia avoidant behavior only, with the ES difference exceeding the MDD criterion of 0.5 SD), but not in children.

Treatment satisfaction (Table 1 and Fig. 1B and C)

In the SAPT arm there was significant improvement for all treatment satisfaction measures except Interference in adults, all measures except Problems and Worries in caregivers, and the key IDSRQ measures (Convenience, Efficacy, and Overall Preference) in children. In the MDI arm there was significant improvement for five IDSRQ measures (BG Burden, Efficacy, Worries, Social Burden, and Overall Preference) in adults but for no IDSRQ measure in children or caregivers.

All significant between-arm differences in change of IDSRQ scores favored SAPT; SAPT arm improvement was greater for key measures (Convenience, Efficacy, and Overall Preference) in adults, children, and caregivers (all P<0.001), with all differences exceeding the MDD criterion (Table 1 and Fig. 1B). In addition, SAPT arm improvement was significantly greater for Problems, Interference, BG Burden, Worries, and Well-being in adults and for BG Burden and Well-being in caregivers (Table 1 and Fig. 1C).

Discussion

In this first large-scale study comparing SAPT (pump+CGM) with optimal conventional insulin therapy (MDI+SMBG) in pump- and CGM-naive adults and children with T1DM and A1C levels above the American Diabetes Association goal of ≤7.0%, SAPT was associated with benefits in diabetes-specific HRQOL and in treatment satisfaction, measures that are likely to be most sensitive to the interventions used in the study. Increases in key treatment satisfaction measures of convenience, efficacy, and overall preference were much greater in the SAPT arm than in the injection therapy arm among adults and children and in children's caregivers, with all between-treatment arm differences exceeding the criterion for a minimally detectable difference. This suggests that SAPT may have positive effects on diabetes treatment satisfaction compared with optimal conventional insulin therapy. The advantages for SAPT in measures of diabetes-specific quality of life (reduced hypoglycemia fear and hypoglycemia-avoidant behavior in adults and reduced hypoglycemia-avoidant behavior in children as reported by caregivers) suggest that SAPT may have positive effects here as well.

The current findings are consistent with those of our earlier study, with fewer subjects and of shorter duration, in which we found greater improvements for SAPT than for MDI+SMBG for treatment satisfaction measures of convenience, efficacy, overall satisfaction, and treatment preference among a small sample of patients with type 1 diabetes during a 16-week randomized controlled trial.6

Our finding of greater between-treatment arm differences in improvement for treatment satisfaction and diabetes-specific quality of life (fear of hypoglycemia) than for generic HRQOL is consistent with previous reports of other diabetes treatments.20,21 We know of no other study comparing SAPT and MDI+SMBG that assessed HRQOL, but there have been studies of pump therapy and of CGM that assessed HRQOL. A recently published article by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation CGM Study Group of children using insulin pump or MDI therapy reported findings similar to those of the current study; after 26 weeks SF-12 PCS and MCS scores (in adults) and PedsQL total scores (in children and caregivers) were largely unchanged in both CGM and SMBG treatment groups, with no significant difference between treatment groups except for a greater improvement in adult CGM patients in SF-12 PCS scores.12 There was also a significantly greater improvement in Hypoglycemia Fear Survey Worry scores among CGM treatment group adults, with no significant between-arm difference in change among children or caregivers in either HFS summary score.

Our findings indicate that adult patients experienced the advantages of SAPT compared with optimal conventional therapy to a greater degree than caregivers or pediatric patients. Among adult patients all diabetes-specific measures (both HFS-II measures and eight of nine IDSRQ measures of treatment satisfaction) improved more in the SAPT treatment group. For pediatric patients we found SAPT advantages for the three key IDSRQ measures (Convenience, Efficacy, and Overall Preference), but not for the other measures; moreover, although there was little difference between adult and pediatric patients in actual improvement in glycemic control, the difference between adults and children in IDSRQ clinical efficacy ES was larger than the minimal meaningful difference. This study is not unique in this respect; others have reported greater HRQOL and treatment satisfaction advantages among adults than children for CGM over SMBG in those using either pump or MDI therapy.12 These findings suggest either that measures of HRQOL and treatment satisfaction are less sensitive in children, or that children are less sensitive to the benefits and burdens of treatment. These possibilities are consistent with the fact that caregivers of pediatric patients experienced greater advantages for SAPT than their children did, with significant differences for some measures of hypoglycemia fear and treatment perceptions in caregivers that did not reach statistical significance in their children. Differences between caregivers and their children in ES for treatment satisfaction Efficacy and Overall Preference were larger than the MDD. The effect size for IDSRQ clinical Efficacy and for Overall Preference in caregivers was almost identical to that in adult patients (1.32 vs. 1.38 for clinical Efficacy and 2.15 vs. 2.27 for Overall Preference).

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large sample of adults and pediatric patients as well as children's caregivers, the study's 52-week duration, and the broad range of HRQOL and treatment satisfaction variables using validated questionnaires. The fact that following 5 weeks of training and initiation for SAPT, all study participants received only standard diabetes care (quarterly physician visits) is also a strength because this approximates the experience patients would have in real-life clinical settings. Study limitations include the fact that MDI patients used CGM during the study, although their perceptions of treatment were regarded as a function only of SMBG. Other limitations include the narrow range of A1C eligible for inclusion (7.4–9.5%), which may limit the trial's generalizability to other diabetes patient populations. In addition, study participants may have been particularly motivated, although it has been suggested that they were generally representative of individuals seeking intensification of insulin therapy.7 Finally, contact with clinical staff during the treatment initiation phase of the study was greater for the SAPT arm to facilitate technical training (mean 10.9 vs. 3.9 h for the MDI group [P<0.01] in the first 3 months of the trial),22 although clinical contacts were designed to be identical for the two groups thereafter, and time with clinical staff was more similar in months 4–12 (mean, 4.8 h in the SAPT group and 4.0 h in the MDI group [P<0.05]).22 Study staff was instructed not to make outgoing calls to either group unless there was a safety concern.

Research implications

Future research should assess the benefits of SAPT in routine clinical use and in comparison with intermediate technology platforms (continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion+SMBG and MDI+CGM) to determine the contribution of each component to overall benefit. Research should assess the degree to which HRQOL and treatment satisfaction benefits are driven by clinical outcomes or require trade-offs between objective clinical benefits and subjective benefits.

Clinical implications

Results suggest that switching from MDI+SMBG to SAPT can be a safe and feasible choice for motivated patients seeking more precise insulin delivery and more frequent blood glucose monitoring data to achieve improved blood glucose control. Clinicians should consider using the STAR 3 education and intervention protocol as a model for implementing SAPT.23

Conclusions

In this first-ever large-scale study of SAPT compared with optimal conventional therapy SAPT had significant PRO advantages, especially for treatment satisfaction in adults, children, and caregivers and hypoglycemia fear in adults and caregivers.

Appendix

STAR 3 Study Group

The principal investigators and study staff are listed by investigational site, and sites are alphabetized by city name: Mountain Diabetes and Endocrine Center (Asheville, NC), W.S. Lane (principal investigator), K. Arey, and T. Przestrzelski; Joslin Diabetes Center (Boston, MA), S. Mehta (principal investigator), L. Laffel (principal investigator), J. Aggarwal, and K. Pratt; University of North Carolina School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, NC), J.B. Buse (principal investigator), M. Duclos, and J. Largay; Ohio State University College of Medicine (Columbus, OH), K. Osei (principal investigator), C. Casey-Boyer, and H. Breedlove; University of Colorado Denver (Denver, CO), R. Slover II (principal investigator), S. Kassels, and S. Sullivan; Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC), J.B. Green (principal investigator) and J. English-Jones; Helen DeVos Children's Hospital (Grand Rapids, MI), M.A. Wood (principal investigator), E. Gleason, and L. Wagner; East Carolina University, Diabetes and Obesity Center (Greenville, NC), R.J. Tanenberg (principal investigator) and C. Knuckey; Rocky Mountain Diabetes and Osteoporosis Center (Idaho Falls, ID), D.R. Liljenquist (principal investigator), J.E. Liljenquist (principal investigator), and B. Sulik; Kingston General Hospital (Kingston, ON, Canada), R.L. Houlden (principal investigator), T. LaVallee, A. Breen, and R. Barrett; Scripps Institute (La Jolla, CA), G. Dailey (principal investigator), R. Rosal, and J. Shartel; Kentucky Diabetes Endocrinology Center (Lexington, KY), L. Myers (principal investigator) and D. Ballard; Endocrinology Diabetes Clinic (Madison, WI), M. Meredith (principal investigator) and C. Trantow; Diabetes Research Institute (Miami, FL), L.F. Meneghini (principal investigator), J. Sparrow-Bodenmiller, and R. Agramonte; International Diabetes Center at Park Nicollet (Minneapolis, MN), R.M. Bergenstal (principal investigator), A.B. Criego, and S. Borgman; Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN), M.E. May (principal investigator), S.N. Davis (principal investigator), and C. Root; Yale University (New Haven, CT), S.A. Weinzimer (principal investigator), L. Carria, and J. Sherr; Children's Hospital of Orange County (Orange, CA), M. Daniels (principal investigator), J.S. Krantz (principal investigator), H. Speer, and J. Less; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA), S.M. Willi (principal investigator), T. Calvano, and E. Garth; Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, OR), A. Ahmann (principal investigator), V. Chambers, and B. Wollam; Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN), Y.C. Kudva (principal investigator) and B. Wirt; University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry (Rochester, NY), C. Orlowski (principal investigator) and S. Bates; Endocrine Research Solutions (Roswell, GA), J.C. Reed III (principal investigator), K. Wardell, and S. Newsome; Memorial University of Newfoundland (St. John's, NL, Canada), C. Joyce (principal investigator), D. Gibbons, and J. O'Leary; Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO), N.H. White (principal investigator) and M. Coleman; Children's Hospital of St. Paul (St. Paul, MN), R.C. McEvoy (principal investigator) and C. Girard; Utah Diabetes Center (Salt Lake City, UT), C.M. Foster (principal investigator), T. Brown, and E. Nuttall; Toronto General Hospital (Toronto, ON, Canada), B.A. Perkins (principal investigator) and A. Orszag; Endocrine Research (Vancouver, BC, Canada), H. Tildesley and B. Pottinger; and Mid-America Diabetes Associates (Wichita, KS), R.A. Guthrie (principal investigator), J. Dvorak, and B. Childs.

STAR 3 Steering Committee

T. Battelino, University Children's Sensor, Ljubljana, Slovenia; S.N. Davis, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; E.S. Horton, Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA; S.W. Lee, Medtronic, Northridge, CA; R.R. Rubin, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD; K.A. Schulman, Duke University, Durham, NC; and W.V. Tamborlane, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the STAR 3 Study Group

Acknowledgments

Medtronic MiniMed provided financial support for this project and provided access to the data.

Author Disclosure Statement

R.R.R. and M.P. received research funds and consulting fees from the insulin pump companies Medtronic MiniMed and Animas. R.R.R. also received research funds and consulting fees from Medingo. R.R.R. participated in the planning and implementation of the study and wrote, reviewed, and approved the article. M.P. analyzed data and wrote, reviewed, and approved the article. No statisticians were involved in the preparation of this article. No medical writers were involved except for formatting of tables and figures.

References

- 1.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan DM. Cleary PA. Backlund JY. Genuth SM. Lachin JM. Orchard TJ. Raskin P. Zinman B Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDICT) Study Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misso ML. Egberts KJ. Page M. O'Connor D. Shaw J. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) versus multiple insulin injections for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD005103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005103.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1464–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch IB. Abelseth J. Bode BW. Fischer J. Kaufman FR. Mastrototaro J. Parkin CG. Wolpert HA. Buckingham BA. Sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy: results of the first randomized treat-to-target study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008;10:377–383. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyrot M. Rubin RR. Patient-reported outcomes for an integrated real-time continuous glucose monitoring/insulin pump system. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:57–62. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergenstal RM. Tamborlane WV. Ahmann A. Buse JB. Dailey G. Davis SN. Joyce C. Peoples T. Perkins BA. Welsh JB. Willi SM. Wood MA STAR 3 Study Group. Effectiveness of sensor-augmented insulin-pump therapy in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:311–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raccah D. Sulmont V. Reznik Y. Guerci B. Renard E. Hanaire H. Jeandidier N. Nicolini M . Incremental value of continuous glucose monitoring when starting pump therapy in patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: the RealTrend study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2245–2250. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyrot M. Rubin RR. Validation and reliability of an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life: the Insulin Delivery System Questionnaire. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:53–58. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoogma RPLM. Hammond PJ. Gomis R. Kerr D. Brutomesso D. Bouter KP. Wiefels KJ. de la Calle H. Schweitzer DH. Pfohl M. Torlone E. Krinelke LG. Bolli GB 5-Nations Study Group. Comparison of the effects of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) and NPH-based multiple daily injections (MDI) on glycaemic control and quality of life: results of the 5-Nations Trial. Diabet Med. 2005;23:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raskin P. Bode BW. Marks JB. Hirsch IB. Weinstein RL. McGill JB. Peterson GE. Mudaliar SR. Reinhardt RR. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injection therapy are equally effective in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, parallel-group, 24-week study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2598–2603. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.JDRF Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Quality-of-life measures in children and adults with type 1 diabetes: JDRF Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2175–2177. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin RR. Peyrot M. Treatment satisfaction and quality of life for an integrated continuous glucose monitoring/insulin pump system compared to self-monitoring plus an insulin pump. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1402–1410. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE. Kosinski M. Dewey JE. How to Score Version Two of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varni JW. Burwinkle TM. Jacobs JR. Gottschalk M. Kaufman F. Jones KL. The PedsQL in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales and type 1 Diabetes Module. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:631–637. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonder-Frederick LA. Schmidt KM. Vajda KA. Greear ML. Singh H. Shepard JA. Cox DJ. Psychometric properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey-II for adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:801–806. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonder-Frederick LA. Fisher CD. Ritterband LM. Cox DJ. Hou L. DasGupta AA. Clarke WL. Predictors of fear of hypoglycemia in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2006;7:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2006.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke WL. Gonder-Frederick LA. Snyder AL. Cox DJ. Maternal fear of hypoglycemia in their children with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1998;11(Suppl 1):189–194. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1998.11.s1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman GR. Sloan JA. Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin RR. Peyrot M. Chen X. Frias JP. Patient-reported outcomes from a 16-week, open label, multicenter study of insulin pump therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:901–906. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peyrot M. Rubin RR. Effect of Technosphere inhaled insulin on quality of life and treatment satisfaction. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:49–55. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamble S. Perry BM. Shafiroff J. Sculman KA. Reed SD. Provider time associated with sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy in type 1 diabetes [abstract] Diabetes. 2011;60(Suppl 1):A238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin RR. Borgman SK. Sulik BT. Crossing the technology divide: practical strategies for transitioning patients from multiple daily injections to sensor-augmented pump therapy. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(Suppl 1):5s–18s. doi: 10.1177/0145721710391107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]