Abstract

Introduction

The Bowel Cancer Screening Programme in England began operating in 2006 with the aim of full roll out across England by December 2009. Subjects aged 60–69 are being invited to complete three guaiac faecal occult blood tests (6 windows) every 2 years. The programme aims to reduce mortality from colorectal cancer by 16% in those invited for screening.

Methods

All subjects eligible for screening in the National Health Service in England are included on one database, which is populated from National Health Service registration data covering about 98% of the population of England. This analysis is only of subjects invited to participate in the first (prevalent) round of screening.

Results

By October 2008 almost 2.1 million had been invited to participate, with tests being returned by 49.6% of men and 54.4% of women invited. Uptake ranged between 55–60% across the four provincial hubs which administer the programme but was lower in the London hub (40%). Of the 1.08 million returning tests 2.5% of men and 1.5% of women had an abnormal test. 17 518 (10 608 M, 6910 F) underwent investigation, with 98% having a colonoscopy as their first investigation. Cancer (n=1772) and higher risk adenomas (n=6543) were found in 11.6% and 43% of men and 7.8% and 29% of women investigated, respectively. 71% of cancers were ‘early’ (10% polyp cancer, 32% Dukes A, 30% Dukes B) and 77% were left-sided (29% rectal, 45% sigmoid) with only 14% being right-sided compared with expected figures of 67% and 24% for left and right side from UK cancer registration.

Conclusion

In this first round of screening in England uptake and fecal occult blood test positivity was in line with that from the pilot and the original European trials. Although there was the expected improvement in cancer stage at diagnosis, the proportion with left-sided cancers was higher than expected.

Keywords: Screening, colorectal cancer, celiac disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, IBD clinical, gastrointestinal cancer, Helicobacter Pylori, colonic adenomas, chromoendoscopy, colorectal cancer screening, inflammatory bowel disease, colonoscopy

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Randomised trials of colorectal (bowel) cancer screening have indicated that a biennial guaiac-based faecal occult blood test has the potential to reduce colorectal cancer mortality by about 25% in those accepting screening and by 16% in those offered screening.

In the UK trials and pilot studies uptake was between 50% and 60%.

Factors such as age, ethnic background, deprivation and gender are known to influence uptake.

What are the new findings?

Overall uptake in this first round of screening was 55–60% in the provinces in keeping with previous studies but was much lower in the London area at only 40%.

Uptake of the offer of colonoscopy in those with an abnormal test was high but only 83% of those with abnormal tests underwent colonoscopy.

Early cancer (Dukes A or B) was found in 70% of those with cancer.

The proportion of screen-detected cancers that were found in the right colon was lower than expected.

How might these impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

If these early results are maintained the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme will achieve the intended 16% reduction in overall bowel cancer mortality.

Different screening strategies may be required to effectively screen for right-sided bowel cancer.

Introduction

Bowel (colorectal) cancer is the cause of 16 000 deaths a year in the UK and is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of death from cancer in both the UK and in Europe.1 2 Although the results of treatment have shown a gradual improvement over the past 30 years, 5-year survival is still only around 50% in the UK and appears to be significantly lower than in other comparable countries.3 4

Randomised trials have shown that screening for bowel cancer using guaiac-based faecal occult blood tests (gFOBts) can reduce mortality by 16% in people offered screening and 25% in those accepting it.5 6 Economic analyses also suggest that screening will be suitably cost-effective with a cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained of < £3000 for gFOBt screening.7 As a consequence many countries have or are introducing bowel cancer screening programmes.8 9 In April 2006 the Department of Health in England agreed funding for a national programme of biennial gFOBt screening of 60–69 year olds. Roll out of the programme started in July 2006 and was complete by January 2010.

This paper reports on the uptake and early outcomes of the first million people screened.

Methods

Identification of population invited for screening

The Bowel Cancer Screening System (BCSS) uses the 82 English NHAIS (National Health Application and Infrastructure Services) systems as its source of demographic information. Software on these NHAIS systems identifies eligible men and women resident in England who are within screening age range and registered with a GP practice. Demographic changes to these people are updated daily.

The screening process

Starting from age 60 all subjects identified for screening are sent an invitation to participate around the time of their birthday and every 2 years thereafter until the age of 70 is reached. Included with the invitation letter is an information leaflet about bowel cancer and the screening process. A second letter containing the FOBt kit and cardboard spatulas follows 1–2 weeks later with instructions for collecting the samples and a prepaid ‘postage safe’ return envelope. The gFOBT used was identical to that used in the pilot (Hemascreen; Immunostics, New Jersey, USA). Each kit contains six windows and subjects are asked to collect two small faecal samples from each of three stools onto the windows. Subjects are not asked to make any dietary restrictions before collecting their samples as such restrictions might have an adverse effect on uptake and have not been clearly shown to reduce the false-positive rate10.

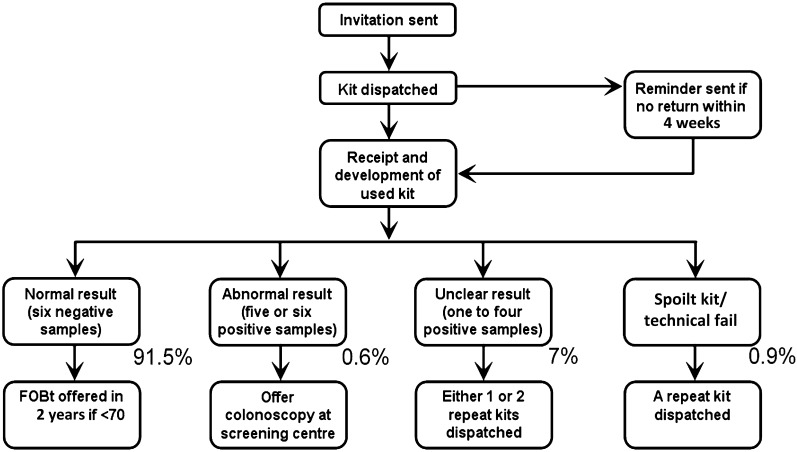

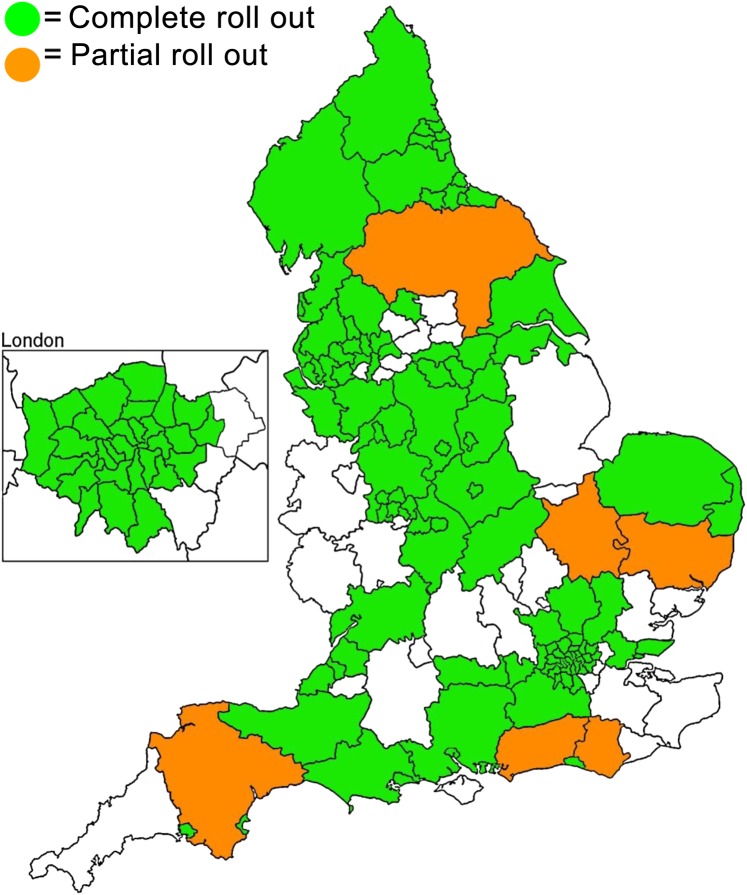

Subjects are asked to return test kits within 14 days of the first sample being collected. Kits are dispatched by, and returned to, one of five testing laboratories (referred to as hubs), each one covering a large region of England as shown in figure 1. Subjects returning kits in which five or six windows test positive are deemed abnormal and are immediately referred to a nurse-run clinic (specialist screening practitioner (SSP) clinic) at their local screening centre (figure 2). Subjects returning kits with 1–4 windows testing positive are invited to repeat the test. If on the second test any window tests positive then that too is deemed abnormal and the subject is referred to the SSP clinic. If a second test is negative subjects are invited to do a third test. If all six windows are negative again then the subject is discharged from that round of screening but if any window is positive then that subject is also referred to the SSP clinic.

Figure 1.

Areas of England covered by five regional Bowel Cancer Screening Programme hubs.

Figure 2.

Bowel Cancer Screening Programme screening pathway. FOBT, faecal occult blood test.

Subjects returning test kits in which all six windows test negative on either the first kit or on a subsequent kit are deemed normal. They are discharged from that screening round to be re-invited in 2 years provided they are still in the screening age range, which was 60–69 years at the time of this analysis.

Subjects with abnormal tests are advised of their test result by first-class post with an offer of an appointment at an SSP clinic within 14 days. These take place at one of a large number of sites operated by 58 designated screening centres. During the clinic consultation, the SSP explains the test result and that further investigation with colonoscopy is needed to reach a diagnosis. The risks, benefits and nature of the colonoscopy procedure are explained and a health assessment completed. If the patient wishes to proceed, an appointment is made within 2 weeks and the bowel preparation is provided with detailed explanation. In <3% of FOB-positive subjects a colonoscopy is deemed not to be appropriate as the first investigation and a CT colonoscopy (2%), CT scan (0.4%) or barium enema (0.3%) is the first investigation performed.

All colonoscopies are undertaken at Joint Advisory Group on GI endoscopy (http://www.thejag.org.uk/) accredited screening centres by screening-accredited screening colonoscopists, who have passed a formal assessment comprising 12 month personal colonoscopy audit, multiple choice questionnaire and performed two directly observed colonoscopies assessed independently by two screening examiners.11 12 Ongoing quality assurance includes assessment of caecal intubation rate, adenoma detection rate, polyp retrieval rate, colonoscopy withdrawal time, comfort score and complications. Screening colonoscopies are allocated 45 min time slots. An SSP accompanies the patient during the procedure and records a detailed dataset onto the single national BCSS database.

Patients are given the results of colonoscopy by the SSP before they leave the department. Where nothing abnormal has been found, the patient is discharged from that round of screening and informed that they will be invited again for screening in 2 years' time (provided that they are still within the eligible age range). Where one or more polyps have been removed, the patient is offered an appointment at an SSP follow-up clinic in the next week. Adenoma surveillance is based on the current British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines.13 If patients with adenomas are categorised as intermediate or high risk, they enter the screening surveillance programme. This surveillance programme is part of the BCSP and surveillance colonoscopies are scheduled and performed by the screening centre. Such patients are sent no further invitations to take part in further FOB testing rounds until they leave surveillance. If patients with adenomas are categorised as low risk, they do not enter the screening surveillance programme, but are discharged from that round of screening and informed that they will be invited again for screening in 2 years' time (provided that they are still within the eligible age range). If a cancer is found, the patient's care is taken over by the hospital's multidisciplinary team for the management of colorectal cancer.

Data on adverse events associated with the screening programme are recorded separately on a standard form which is sent electronically to the regional quality assurance reference centre and national office as well as being recorded on the screened subject's record. Adverse event records maybe submitted by the hubs or screening centres.

BCSS database

The BCSS is part of the ‘Open Exeter’ suite of applications. The ‘engine’ of BCSS itself is an Oracle database. All of the system logic and processing is performed in Oracle which provides the results to the Java front end for display to the user. As of October 2010 there were 1126 BCSS user accounts, of which 50% had been active in the previous 30 days. Since the implementation of BCSS in June 2006 to October 2010 there have been 11 major software updates. Currently the BCSS database size is 280 GB and includes the demographics for 11.2 million people within the screening age range (currently 59–74+), their episode history, the results of their FOBT tests and diagnostic tests and histology information.

The main analyses are based on records downloaded from the database in October 2008 after almost 2.1 million invitations while the analysis of uptake of screening by socioeconomic deprivation and hub is based on a later download performed in January 2009 after 2.6 million invitations. This analysis is based on uptake rates for the smallest geographical unit that is routinely recorded by the BCSP—namely, postcode sector. Postcode sectors are defined by the first inward digit of the postcode (the UK equivalent of a zip code) and contain an average of 3000 addresses. Data from 7040 postcode sectors were included (over 85% of the total); with an average of 378 invitations per sector. We excluded 1128 postcode sectors for which we could not retrieve census data on ethnic diversity.14 A composite indicator of socioeconomic deprivation for each postcode sector was derived using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) from 2007, which uses census-derived indicators of income, education, employment, environment, health and housing at small-area level to generate a scale from 0 (least deprived) to 80 (most deprived).15 We used continuous measures of IMD scores and compared adjusted uptake across quintiles of the national distributions for descriptive purposes. Data were stratified by gender, age group (60–65 years vs 66–69 years) and screening hub.

Definitions

The following terms are defined as:

Uptake (%)—Subjects returning 1+ kits/subjects invited (sent invitation (S1) letter);

Positivity (%)—Subjects with positive gFOBt offered SSP appointment/subjects returning any kits;

Attendance for investigation (%)—Subjects (patients) attending for investigation/subjects offered SSP appointment;

Subjects with high risk adenomas—Five or more adenomas or three or more with at least 1 ≥1 cm diameter;

Intermediate risk adenomas—Three or four small (<1 cm diameter) adenomas or one adenoma ≥1 cm diameter;

Low risk adenomas—One or two adenomas <1 cm diameter.

Results

By October 2008 the screening programme had been rolled out to 99 primary care trusts, and screening colonoscopy was being performed in 36 screening centres across England (figure 3). Almost 2.1 million 60–69 year olds had been sent invitations to be screened and 52.0% had returned gFOBt kits, 49.6% (510 864) of men invited and 54.4% (568 429) of the women invited.

Figure 3.

Extent of roll out of Bowel Cancer Screening Programme by primary care trusts in October 2008.

Uptake, positivity and attendance for investigation

Table 1 shows uptake, positivity and investigation attendance according to health authority area. While overall uptake was 4.8% higher in women (χ2 =1494, p<0.00001), this difference was greater in London and in the south of England at over 6% and lowest in the North East at only 1.4%.

Table 1.

Uptake and positivity by numbers invited, strategic health authority area and gender (after first 2 million invitations)

| Strategic health authority | Men | Women | ||||||||||||

| Invited | Kit returned | Uptake (%) | Abnormal result | % | Attended for investigation | % | Invited | Kit returned | Uptake (%) | Abnormal result | % | Attended for investigation | % | |

| North East | 101 726 | 53 140 | 52.2 | 1271 | 2.4 | 1111 | 87 | 104 669 | 56 098 | 53.6 | 701 | 1.2 | 620 | 88 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 85 441 | 45 147 | 52.8 | 988 | 2.2 | 809 | 82 | 87 132 | 50 177 | 57.6 | 588 | 1.2 | 499 | 85 |

| North West | 174 264 | 85 506 | 49.1 | 2515 | 2.9 | 2141 | 85 | 178 708 | 93 521 | 52.3 | 1531 | 1.6 | 1272 | 83 |

| West Midlands | 122 242 | 63 227 | 51.7 | 1590 | 2.5 | 1288 | 81 | 123 609 | 69 744 | 56.4 | 1057 | 1.5 | 897 | 85 |

| East Midlands | 82 115 | 44 057 | 53.7 | 1172 | 2.7 | 952 | 81 | 82 262 | 47 730 | 58.0 | 829 | 1.7 | 649 | 78 |

| East of England | 105 422 | 58 493 | 55.5 | 1406 | 2.4 | 1240 | 88 | 107 488 | 66 353 | 61.7 | 958 | 1.4 | 829 | 87 |

| London | 194 564 | 71 620 | 36.8 | 2052 | 2.9 | 1595 | 78 | 194 138 | 83 502 | 43.0 | 1531 | 1.8 | 1209 | 79 |

| South Central | 22 466 | 10 430 | 46.4 | 248 | 2.4 | 183 | 74 | 22 136 | 11 813 | 53.4 | 160 | 1.4 | 123 | 77 |

| South East Coast | 56 363 | 31 387 | 55.7 | 609 | 1.9 | 515 | 85 | 58 817 | 36 513 | 62.1 | 389 | 1.1 | 309 | 79 |

| South West | 84 708 | 47 137 | 55.6 | 925 | 2.0 | 774 | 84 | 85 837 | 52 978 | 61.7 | 586 | 1.1 | 503 | 86 |

| Total | 1 029 311 | 510 864 | 49.6 | 12 776 | 2.5 | 10 608 | 83 | 1 044 796 | 568 429 | 54.4 | 8330 | 1.5 | 6910 | 83 |

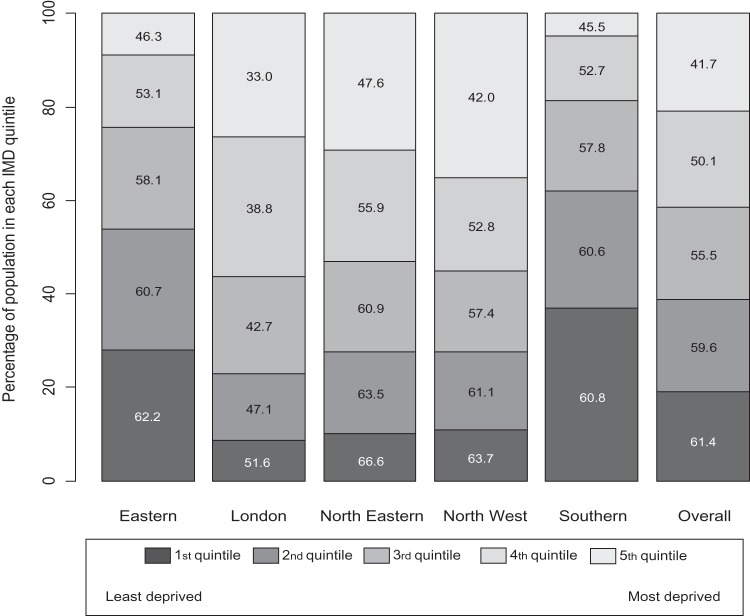

When the populations invited were stratified according to socioeconomic indices (IMD quintiles) and by screening hub as shown in figure 4 uptake was as expected highest in the least deprived areas, being 61.4% overall and lowest in the most deprived areas at 41.7% overall. However, there was striking variation in uptake between hubs within IMD quintiles with 66.6% of the population in the lowest IMD quintile of the North-Eastern hub returning their kits compared with only 51.6% in the same IMD quintile of the London hub. Similarly, in areas with the highest deprivation, uptake ranged from only 33% in London to 47.6% in the North East. Indeed for every IMD quintile, uptake was highest in areas covered by the North-Eastern hub and lowest in the London area.

Figure 4.

Uptake of faecal occult blood test screening (%) by quintile of Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score within each Bowel Cancer Screening Programme hub

The proportion of subjects returning kits with positive (abnormal) test results was 2.0% and was higher in men (2.5%) than women (1.5%) (χ2=1445, p<0.00001). This difference was of similar magnitude across all areas.

Of the 21 106 with positive (abnormal) test results, 94% went on to attend an SSP clinic, with 6% not attending despite reminders. The proportions subsequently undergoing investigation (83%) were the same in men and women. Of those attending the SSP clinic, investigation was thought to be not necessary or not appropriate in 7.6% and 3.7% either declined the offer of investigation or failed to attend.

Findings after investigation

A total of 17 518 subjects with abnormal gFOBts attended for investigation. For 98.1% (17 192) the first investigation performed was a colonoscopy and the remaining few had either CT colography (1.2%), a barium enema (0.4%) or an abdominal CT scan (0.3%). A further 943 colonoscopies were performed later in the initial diagnostic process (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Diagnostic test results after investigation of 17 518 FOB positives after first 2 million invitations

| Polyps | ||||||||

| Missing | Cancer | Normal | Low risk | Intermediate | High risk | Other | Total | |

| Men | 682 | 1230 | 2576 | 1736 | 2043 | 1293 | 1048 | 10 608 |

| 6.4% | 11.6% | 24.3% | 16.4% | 19.3% | 12.2% | 9.9% | 100.0% | |

| Women | 338 | 542 | 2622 | 1007 | 1007 | 428 | 966 | 6910 |

| 4.9% | 7.8% | 37.9% | 14.6% | 14.6% | 6.2% | 14.0% | 100.0% | |

| Total | 1020 | 1772 | 5198 | 2743 | 3050 | 1721 | 2014 | 17 518 |

| 5.8% | 10.1% | 29.7% | 15.7% | 17.4% | 9.8% | 11.5% | 100.0% | |

FOB, faecal occult blood; VES, ????.

Table 3.

Yield of cancer and all advanced neoplasia by numbers invited, strategic health authority area and gender after first 2 million invitations

| Strategic health authority | Men | Women | ||||||||||

| Invited | Attended for investigation | Cancer | % | Advanced neoplasia* | % | Invited | Attended for investigation | Cancer | % | Advanced neoplasia* | % | |

| North East | 10 1726 | 1111 | 132 | 11.9 | 474 | 43 | 104 669 | 620 | 48 | 7.7 | 183 | 30 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 85 441 | 809 | 102 | 12.6 | 329 | 41 | 87 132 | 499 | 46 | 9.2 | 162 | 32 |

| North West | 174 264 | 2141 | 257 | 12 | 956 | 45 | 178 708 | 1272 | 90 | 7.1 | 369 | 29 |

| West Midlands | 122 242 | 1288 | 147 | 11.4 | 560 | 43 | 123 609 | 897 | 67 | 7.5 | 230 | 26 |

| East Midlands | 82 115 | 952 | 103 | 10.8 | 392 | 41 | 82 262 | 649 | 50 | 7.7 | 180 | 28 |

| East of England | 105 422 | 1240 | 152 | 12.3 | 553 | 45 | 107 488 | 829 | 61 | 7.4 | 241 | 29 |

| London | 194 564 | 1595 | 156 | 9.8 | 626 | 39 | 194 138 | 1209 | 95 | 7.9 | 323 | 27 |

| South Central | 22 466 | 183 | 15 | 8.2 | 68 | 37 | 22 136 | 123 | 10 | 8.1 | 25 | 20 |

| South East Coast | 56 363 | 515 | 63 | 12.2 | 237 | 46 | 58 817 | 309 | 33 | 10.7 | 99 | 32 |

| South West | 84 708 | 774 | 103 | 13.3 | 371 | 48 | 85 837 | 503 | 42 | 8.3 | 165 | 33 |

| Total | 1 029 311 | 10 608 | 1230 | 11.6 | 4566 | 43 | 104 4796 | 6910 | 542 | 7.8 | 1977 | 29 |

Advanced neoplasia includes all cancer and adenomatous polyps classed as high and intermediate risk.

The outcome of these investigations was not available on BCSS for 1020 (5.8%). One thousand seven hundred and seventy-two subjects were recorded as having a colorectal cancer (10.1%) with the proportion being higher in men (11.6%) than in women (7.8%) (χ2=53, p<0.0001). A further 12% of men and 6.2% of women investigated were found to have colorectal adenomatous polyps defined as high risk and therefore invited to have another colonoscopy in 1 year as recommended by the BSG guidelines. An additional 19.3% of men and 14.6% of women had polyps defined as intermediate risk for which a repeat colonoscopy is offered in 3-years' time. Thus advanced colorectal neoplasia (all cancers and adenomas classified as high or intermediate risk) for which further treatment or investigation was required was present in 43% of men and 29% of women investigated.

In 11.5% (2014) of those investigated other abnormalities were recorded as being present. Most commonly this was diverticular disease being the only finding in 33% and being present in association with other conditions in another 15%. Ulcerative colitis was found in a further 15% and was recorded as being ‘active’ in 5%. Other conditions less commonly recorded were angiodysplasia (4.5%), Crohn's disease (3.2%), solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (2.0%) and radiation proctitis (1.8%). Haemorrhoids were recorded as the only finding in 15%.

Cancer by site and stage

Table 4 shows the site distribution for 1716 of the 1772 colorectal cancers detected; no site data was available on BCSS for 56 cancers. In 28.7% the cancer was recorded as being in the rectum or rectosigmoid colon and overall 77.3% were recorded as being left-sided colorectal cancers while only 14.3% were recorded as being in the right colon. As expected right-sided cancer was more commonly found in women (19.2%) than in men (12.2%) and conversely rectal cancer was less common in women (20.3%) than men (28.5%) (χ2=10.3, p=0.0014)

Table 4.

Site distribution of 1730 screen detected cancers

|

*No site coded for 37 cancers and three coded as anal and two as ileal.

Cancer staging data were missing for 11.2% (198/1772). Table 5 shows the Dukes stage for the remaining 1574. A total of 71.3% of the cancers were polyp cancers or Dukes A or B and so potentially curable which can be compared with the 72% found with the same Dukes stage in the English pilot. Stage distribution was similar in men and women (tables 4 and 5).

Table 5.

Duke's stage of bowel cancers detected after first investigation of first million people screened in England

|

*In 198 staging data not available.

Adverse events

The most commonly reported serious adverse event was bleeding following polypectomy, for which there were 42 reports. In many of these reports this was managed without admission to hospital but in at least 12 cases bleeding was deemed sufficiently serious to warrant admission. Colonic perforations were reported after 17 colonoscopies, including one patient who needed an emergency right hemicolectomy 12 days after screening colonoscopy; none of these patients died. Post-colonoscopy abdominal pain was reported as a serious adverse event on 14 occasions and in five this resulted in an unplanned hospital admission. One patient had a ruptured spleen after colonoscopy and another developed fever and reported passing blue-coloured urine, which resolved within 10 h of the colonoscopy. There were a further four reports of unplanned admissions on account of a patient being unwell after colonoscopy.

Six deaths were reported to the National Office. None of the deaths reported were a direct consequence of the screening process. Four of the deaths occurred after colectomies for screen-detected cancers and two appeared to be unconnected with the screening programme (one sudden death 24 days after a screening colonoscopy and one head injury after falling downstairs 19 days after a screening colonoscopy).

Discussion

The evidence from the randomised trials of gFOBt screening suggests that a 16% reduction in colorectal cancer mortality should be achievable in a national programme. However, the trials were performed by dedicated teams working with relatively small populations. It is therefore important to examine whether the early outcomes of the BCSP in England are in keeping with expectations from the trials and pilot studies.

Reassuringly the overall uptake of the offer of screening across England was 52%, with uptake outside London ranging between 55% and 60% compared with 40% in London.16 These figures are similar to those found in both the Nottingham trial (55% in 60–69 year olds for first invitations) in the 1980s and that obtained in the English pilot in 2000 (57%).17 18 That the uptake is not higher than that obtained in the Nottingham trial 20 years ago might be regarded as disappointing but in the trial the invitation letters were sent by the subject's general practitioner and a general practitioner's endorsement has been found to increase uptake.19 Similarly, the gender difference in uptake is no surprise, although recent unpublished data suggest that this diminishes in those over age 70 who are now being invited.

What was unexpected was the degree of difference in uptake by region. While uptake was generally lower in areas with greater deprivation, uptake in the North-East region was 3–5% higher for each quintile of IMD score as shown in figure 4. In contrast uptake was substantially lower throughout the London region for each IMD quintile. The explanations for the lower uptake remain to be established but may involve problems with undelivered mail, the greater ethnic mix, large immigrant population and greater use of private healthcare in the London area. It is notable that low uptake is seen in the breast and the cervical cancer screening programmes in London.20–22 Uptake has been analysed in more detail elsewhere.16 23

Overall positivity at 2.0% was identical to that found in the pilot for 60–69 year olds and marginally lower than the 2.1% figure for the Nottingham trial.17 Positivity was 67% higher in men than women and also higher in areas with greater deprivation as was also seen in the trial and in the pilot both in England and in Scotland.24 25 While these variations in positivity between areas may appear small, the impact on demand for screening colonoscopies in individual screening centres is clearly substantial. A sustained 2.5% positivity rate in an area with average acceptance rates will result in a 25% greater demand for colonoscopy in that screening centre compared with the national average.

About 10% of people attending for colonoscopy were found to have cancer, a figure very much in line with the pilot and with the Nottingham trial, as was the higher rate in men. Numbers are not large enough yet to reliably analyse regional patterns.

Perhaps the most unexpected finding was the proportion of left-sided cancers which at 77% is substantially higher than the 66% found in non-screen detected colorectal cancer (CRC).2 In comparison, of the 236 screen-detected cancers in the Nottingham trial,74% were recorded as being in the rectum and sigmoid colon while in the pilot the proportion that were left sided was not reported.17

Whether this increase is a consequence of prevalence round screening or a general consequence of CRC screening is not clear. Several recent studies of colonoscopic CRC screening have highlighted the ineffectiveness of such screening in protecting from right-sided CRC and raised the possibility that the biology of right-sided CRC may be more aggressive and hence less amenable to detection by screening.26–28 While in some of these studies incomplete colonoscopies might also be a factor this appears to be an unlikely explanation within the BCSP data as the caecal intubation rates are carefully documented, and in the most recent analysis of over 36 000 BCSP colonoscopies the mean rate was 95%.29 Another possibility is that right-sided cancers tend to produce detectable occult bleeding when they are larger than left-sided cancers. In support of this a recent analysis from one of the screening centres has found that those with right-sided cancers were more likely to have had a strong positive gFOBt (5–6 windows positive) and be at an advanced stage (Dukes stage B, C or D) than the left-sided cancers.30

Our analysis has several strengths. First, it covers most of England and is considerably larger than other analyses done at this stage. Second, it is a ‘real-world’ analysis using the BCSP data as it has been collected, thus reflecting the screening process on the ground. However, as a ‘real-world’ analysis we have had to accept the limitations of the data available, including some missing data for important variables such as cancer stage and outcome of investigations. For some missing data it was possible for screening centre staff to retrieve records and update the BCSS records but this analysis has highlighted in particular the need to ensure that the staging data are collected with the pathology data.

There were some other limitations. Perhaps the most important is that this was an analysis of the prevalent screening round and we do not know how far the patterns described will be maintained in subsequent rounds of screening. The higher than expected proportion of left-sided cancers is possibly a reflection of prevalent round screening. Another limitation was the reliance on area-level statistics for socioeconomic deprivation. Associations observed in area-based analyses are likely to underestimate individual effects, so the true extent of disparities may be higher. In some areas data were missing for key variables such as findings from investigation and cancer stage. We are also limited in making some comparisons with results from other screening programmes as the classification of the malignancy risk for adenomas found at colonoscopy is that of the BSG guidelines.13 This classification ignores histological features such as villosity and dysplasia as histological subtyping of adenomas is subjective and the reproducibility has been found to be poor. Surveillance guidelines of other nations vary and this makes direct comparison with other studies difficult.

These early results indicate that the BCSP in England is on track to match the 16% reduction in CRC mortality found in the randomised trials of gFOBt screening.5 6 It is encouraging also that uptake outside London was generally good and quite high by international standards. The intention is to replace the gFOBt with a faecal immunochemical test (FIT) in the next few years and based on the Dutch experience using a single FIT we might expect a 25% increase in uptake and up to a doubling of the cancer detection rate.31 However moving to a FIT will require a substantial increase in colonoscopy capacity.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: RFAL conceived the study, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JP conceived the study, and contributed to writing the manuscript. CN provided and contributed to analysing the data. LC contributed to writing the manuscript. MDR contributed to analysing the data and writing the manuscript. CvW contributed data and contributed to the analysis

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Stelliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:765–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer Statistics: 26 Types of Cancer: Bowel (colorectal cancer)—UK incidence statistics Bowel Cancer Research UK. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/bowel/incidence/

- 3. Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet 2011;377:127–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morris EJ, Sandin F, Lambert PC, et al. A population-based comparison of the survival of patients with colorectal cancer in England, Norway and Sweden between 1996 and 2004. Gut 2011;60:1087–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Towler B, Irwig L, Glasziou P, et al. A systematic review of the effects of screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, hemoccult. BMJ 1998;317:559–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1541–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tappenden P, Chilcott J, Eggington S, et al. Option appraisal of population-based colorectal cancer screening programmes in England. Gut 2007;56:677–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benson VS, Patnick J, Davies AK, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of 35 initiatives in 17 countries. Int J Cancer 2008;122:1357–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. International Cancer Screening Network Inventory of Colorectal Cancer Screening Activities in ICSN Countries. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/icsn/colorectal/screening.html

- 10. Pignone M, Campbell MK, Carr C, et al. Meta-analysis of dietary restriction during fecal occult blood testing. Eff Clin Pract 2001;4:150–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme Accreditation of Screening Colonoscopists. BCSP Implementation Guide No 3 (Version5). 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 12. NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme Quality Assurance Guidelines for Colonoscopy. NHS BCSP Publication No.6, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010;59:666–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Office for National Statistics Census Key Statistics for postcode sectors in England and Wales, 2001. London: Crown Copyright, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noble M, McLennan D, Wilkinson K, et al. The English Indices of Deprivation 2007. London: Communities and Local Government, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16. von Wagner C, Baio G, Raine R, et al. Inequalities in participation in an organized national colorectal cancer screening programme: results from the first 2.6 million invitations in England. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:712–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UK Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Group Results of the first round of a demonstration pilot of screening for colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom. BMJ 2004;329:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zajac I, Whibley A, Cole SR, et al. Endorsement by the primary care practitioner consistently improves participation in screening for colorectal cancer: a longitudinal analysis. J Med Screen 2010;17:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. NHS Cervical Screening Programme, England 2009–10. Published by The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/ ISBN 978-1-84636-469-3. [Google Scholar]

- 21. NHS Breast Screening Programme, England 2008–09. Published by The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/ ISBN 978-1-84636-374-0. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eilbert KW, Carroll K, Peach J, et al. Approaches to improving breast screening uptake: evidence and experience from Tower Hamlets. Br J Cancer 2009;101:564–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nnoaham KE, Frater A, Roderick P, et al. Do geodemographic typologies explain variations in uptake in colorectal cancer screening? An assessment using routine screening data in the south of England. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32:572–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steele RJ, Kostourou I, McClements P, et al. Effect of gender, age and deprivation on key performance indicators in a FOBT-based colorectal screening programme. J Med Screen 2010;17:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weller D, Coleman D, Robertson R, et al. The UK colorectal cancer screening pilot: results of the second round of screening in England. Br J Cancer 2007;97:1601–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, et al. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, et al. Protection from right-and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers AA, et al. The reduction in colorectal cancer mortality after colonoscopy varies by site of the cancer. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1128–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee TJ, Rutter MD, Blanks RG, et al. Colonoscopy quality measures: experience from the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Gut 2011; Published Online First: 22 September 2011 doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee TJ, Clifford GM, Rajasekhar P, et al. High yield of colorectal neoplasia detected by colonoscopy following a positive faecal occult blood test in the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. J Med Screen 2011;18:82–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology 2008;135:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]