Abstract

(Macro)autophagy is a cellular membrane trafficking process that serves to deliver cytoplasmic constituents to lysosomes for degradation. At basal levels, it is critical for maintaining cytoplasmic as well as genomic integrity and is therefore key to maintaining cellular homeostasis. Autophagy is also highly adaptable and can be modified to digest specific cargoes to bring about selective effects in response to numerous forms of intracellular and extracellular stress. It is not a surprise, therefore, that autophagy has a fundamental role in cancer and that perturbations in autophagy can contribute to malignant disease. We review here the roles of autophagy in various aspects of tumor suppression including the response of cells to nutrient and hypoxic stress, the control of programmed cell death, and the connection to tumor-associated immune responses.

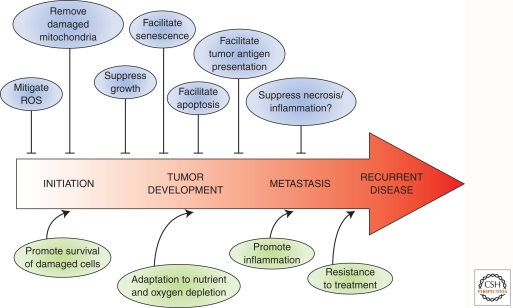

In healthy cells, autophagy protects against malignant disease by maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, upon transformation, activation of autophagy can promote and suppress cancer progression.

THE MOLECULAR MECHANISMS AND TYPES OF AUTOPHAGY

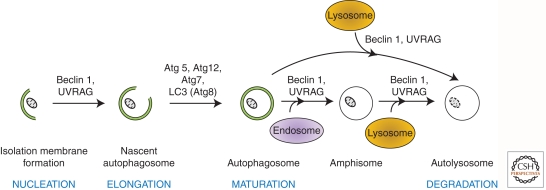

“Autophagy” is broadly defined as a mechanism by which intracellular and extracellular substrates are delivered to lysosomes for degradation. This process is required for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis (Mizushima et al. 2008), generation of amino acids for sustained viability during periods of starvation (Cuervo 2004; Ciechanover 2005), and enhanced protection against pathogens (Shoji-Kawata and Levine 2009). On the basis of the delivery route and cargo specificity, three different types of autophagy have been distinguished—macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (Mizushima et al. 2008). Of these, macroautophagy, which is often simply (and hereafter) referred to as autophagy, is the most characterized form and has been extensively researched in yeast and mammals. It is defined by the sequestration of bulk cytoplasm and organelles in double-membrane organelles termed autophagosomes (Fig. 1) (Eskelinen and Saftig 2009). In contrast, microautophagy is characterized by the direct uptake of cytoplasmic substrates by the invagination of the lysosomal membrane, and CMA by the shuttling of soluble proteins into the lysosome via lysosomal chaperone proteins (Mizushima et al. 2008).

Figure 1.

Cellular mechanism and molecular regulators of autophagy in eukaryotes. NUCLEATION: Beclin 1(Atg6) and UVRAG (UV irradiation resistance–associated gene), are required for the formation of the isolation membrane for sequestering the autophagic substrate. ELONGATION: The closure of the isolation membrane to form autophagosomes causes sequestration/entrapment of cytoplasmic constituents. This requires the conjugation of Atg5 and Atg12 and is catalyzed by Atg7 (E1-like enzyme). Meanwhile, pro-LC3 (Atg8) is cleaved to form LC3-I, which is then lipidated to form LC3-II. MATURATION: Autophagosomes dock and fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes. Although the molecular mechanism is not fully understood, Beclin 1 and UVRAG are thought to mediate this process. Alternatively, autophagosomes can fuse with endosomal vesicles, such as endosomes and multivesicular bodies, to form amphisomes, which eventually dock with lysosomes. DEGRADATION: After fusion with lysosomes, autolysosomes are generated where the sequestered materials are hydrolyzed. The inner membrane of autophagosomes and the cargoes are degraded by lysosomal enzymes, and breakdown products are released back into the cytosol.

Autophagy regulators are conserved from yeast to mammals, and they are the products of AuTophaGy(Atg)-related genes (Xie and Klionsky 2007). The role of several Atg proteins in autophagy is highlighted in this article and is depicted in Figure 1, but for a more extensive review of these factors, see Das et al. (2012). An alternative form of macroautophagy has also been described that does not rely on the complete cascade of Atg signaling. This form of autophagy has been termed “non-canonical” or “alternative autophagy,” and its relevance in relation to “classical” autophagy is currently a matter of debate (Scarlatti et al. 2008; Nishida et al. 2009; Klionsky and Lane 2010). One possibility is that alternative autophagy is adopted when cells fail to activate canonical autophagy owing to mutations in the cluster of Atg genes.

Although autophagy was initially considered a nonselective cellular process, the specific catabolism of cellular organelles like mitochondria, peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum, and ribosomes has been documented and is termed “mitophagy” (Kissova et al. 2004; Lemasters 2005), “pexophagy” (Sakai et al. 2006), “ER-phagy/reticulophagy” (Bernales et al. 2007), and “ribophagy” (Kraft et al. 2008), respectively.

In general, the role of autophagy to maintain cellular homeostasis requires the versatility to recognize a diverse range of substrates and the ability to regulate or respond to specific cellular pathways and stimuli. This reflects a complex signaling network in the regulation of autophagy. Collectively, this process is fundamental and indispensable such that in response to a block in the canonical signaling cascades, one can imagine that cells adopt alternative routes to activate autophagy in response to intracellular and extracellular cues that may not be equivalent, but are sufficient to sustain viability.

It is now well established that autophagy is connected to tumor development, although the exact roles played by the process at various stages of cancer progression are not yet clear and in some cases are contradictory. In the following sections, we outline the current knowledge regarding the regulation of autophagy in cancer and its impact on various processes that protect against malignant disease. Finally, we speculate as to new areas in cancer where autophagy may be important, and we discuss the possibility of targeting autophagy for cancer therapy.

AUTOPHAGY: FROM MOLECULES TO CANCER

The link between autophagy and cancer is now broad-based (Rosenfeldt and Ryan 2011) but was established based on two principal observations. First, it was found that BECN1, the gene encoding Beclin 1 and the ortholog of yeast Atg6, is monoallelically deleted in breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers (Aita et al. 1999; Liang et al. 1999). In addition, ectopic overexpression of BECN1 in MCF7 cells, which have extremely low levels of endogenous Beclin 1, resulted in activation of autophagy coincident with decreased proliferation and inhibition of tumorigenesis (Liang et al. 1999). Consistently, ectopic overexpression of BECN1 in colon cancer cell lines with low expression of this gene results in growth inhibition (Koneri et al. 2007). Subsequent to these studies, mutations in other autophagy-related genes including Atg2B, Atg5, Atg9B, Atg12, and UVRAG, have been documented in gastric and colorectal cancers (Kim et al. 2008; Kang et al. 2009).

The second line of evidence, which consolidated a connection between autophagy and cancer, came from a series of studies involving genetically modified mouse models lacking autophagy regulators. It was found first in mice hemizygous for BECN1, and later in mice lacking Atg4C and BIF1, that a deficiency in these autophagic factors can lead to an increased incidence of tumor formation (Qu et al. 2003; Yue et al. 2003; Marino et al. 2007; Takahashi et al. 2007). Interestingly, however, in the case of mosaic deletion of Atg5 and liver-specific deletion of Atg7, only benign lesions were observed in the liver. Moreover, the mosaic loss of Atg5 in other tissues did not have any effect on tumor formation—either benign or malignant (Takamura et al. 2011). This implies that certain autophagy regulators—in this case, Atg5—may be redundant with respect to tumor suppression in many tissues and that in liver autophagy might prevent tumor initiation, but is required for tumor progression. Having said that, it should be pointed out that some autophagy regulators also control other cellular processes. For example, Beclin 1 also regulates endocytosis. Thus, the resulting tumor phenotype associated with mutation in these versatile regulators may be caused by autophagy-independent mechanisms or by synergistic effects on autophagy and other cellular mechanisms.

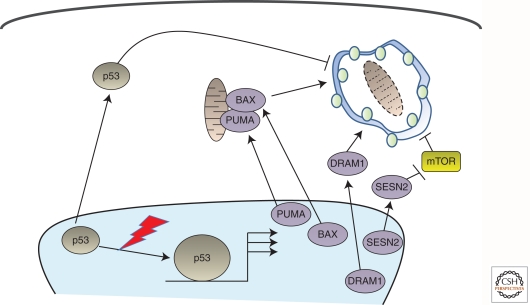

A plethora of genes, which are known to be perturbed in cancer, have now also been reported to modulate autophagy (for review, see Rosenfeldt and Ryan 2009). For example, the well-established tumor suppressor p53—the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer—has been reported to modulate autophagy both positively and negatively (Fig. 2) (Ryan 2011). Its positive effects on autophagy have been shown to occur via modulation of mTOR and through transcriptional up-regulation of the autophagy promoters Sestrin-2 and damage-regulated autophagy modulator-1 (DRAM-1) (Feng et al. 2005; Crighton et al. 2006, 2007; Maiuri et al. 2009). DRAM-1 has also been reported to be down-regulated in certain cancers indicating a direct role of this p53 target gene in tumor suppression (Crighton et al. 2006, 2007).

Figure 2.

p53 modulates autophagy in multiple ways. Basal levels of p53 target repression of autophagy from within the cytoplasm. In response to cellular stress, the levels of p53 become elevated and accumulate in the nucleus. This results in activation of a series of target genes that positively regulate autophagy. PUMA and BAX also localize to mitochondria. DRAM-1, in contrast, localizes to lysosomes, and Sestrin-2 modulates autophagy via mTOR. SESN2, the gene encoding Sestrin-2.

p53 has, however, also been shown to be a negative regulator of autophagy within the cytoplasm (Tasdemir et al. 2008). These dual effects on autophagy are not exclusive to p53. The potent oncogene Ras has also been shown to promote as well as inhibit autophagy (Furuta et al. 2004; Elgendy et al. 2011). Although these findings add to the connection between autophagy and cancer, the apparently conflicting reports may at first seem difficult to reconcile. It must be remembered, however, that multiple different forms of cellular stress occur during tumor development, and these observations may simply reflect different positive and negative effects of autophagy at different stages of the disease.

Additionally, many of these observations are conducted in transformed cell lines, which differ biologically and may not represent what happens in a genuine tumor microenvironment. As such, these results need to be consolidated through sophisticated and thorough in vivo genetically modified mouse models of cancer.

STIMULATING AUTOPHAGY IN CANCER

Autophagy occurs constitutively, but when cells are exposed to unfavorable conditions, autophagy is activated above basal levels to counteract “stress” and to promote cellular homeostasis. This switch from default housekeeping to a specific cytoprotective role is triggered by various stimuli. In cancer, for example, a variety of adverse and hostile conditions that result in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can lead to protein and DNA damage that destabilizes cellular homeostasis (Dewaele et al. 2010).

Under normal conditions, our cells are constantly breaking down macromolecules found abundantly in the surrounding environment for the synthesis of new building blocks and to provide energy to sustain their survival. However, under conditions in which nutrients are scarce, as occurs in the poorly vascularized regions of developing tumors, autophagy is activated as a mechanism to provide nutrients from within the cell in order to sustain viability for a limited period until external nutrients become available (Kuma et al. 2004; Lum et al. 2005a,b). In fact, several evolutionarily conserved nutrient sensors such as mTOR, AMPK, and Sirtuins are regulators of autophagy (Rosenfeldt and Ryan 2009, 2011; Kroemer et al. 2010; Mehrpour et al. 2010). In addition, cellular compartments have recently been identified that enable linkage between autophagy and mTOR (Narita et al. 2011). The importance of this response is exemplified by the fact that when cells are deprived of amino acids, mature autophagic vacuoles have been reported to occupy ∼1% of the cytoplasm (Mizushima et al. 2001). Likewise, under growth factor–limiting conditions, hematopoietic cells activate autophagy to produce ATP for survival (Lum et al. 2005a). Using similar measurements, glucose and serum withdrawal have also been shown to induce autophagy, although the net outcome in these situations often skews toward cell death (Aki et al. 2003; Steiger-Barraissoul and Rami 2009).

In addition to nutrient deprivation, metabolic stress is also caused by hypoxia. Solid tumors contain poorly vascularized regions that are very hypoxic. Studies have now shown that cells within these areas display high levels of macroautophagy (Degenhardt et al. 2006). It was concluded from this study that tumor cells rely heavily on autophagy to survive. The most documented hypoxic signaling pathway involves the activation of the hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF), which is composed of α and β subunits. The HIF1α subunit is affected by changes in oxygen concentration and modulates genes involved in regulating erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, energy metabolism, pH regulation, cell migration, and tumor invasion (Mazure and Pouyssegur 2010). Another HIF family member, HIF2α, is also stimulated by hypoxia, and both HIF1α and HIF2α, as well as the autophagy regulator Beclin 1, have been shown to be required for prosurvival hypoxia-induced autophagy in normal and cancer cell lines (Zhang et al. 2008; Bellot et al. 2009; Wilkinson et al. 2009). In tumor cells, this response is also enhanced by autocrine growth factor signaling via PDGF receptors, leading to enhanced HIF activity and a robust and selective autophagic response to promote cell survival (Wilkinson and Ryan 2009; Wilkinson et al. 2009).

Several reports have also shown that hypoxia can stimulate autophagy in an HIF-independent manner (Pursiheimo et al. 2009). Hypoxia-induced autophagy removes the autophagy “adaptor” and signaling protein p62/SQSTM1, a well-known autophagic substrate, suggesting a link between p62/SQSTM1 and the regulation of hypoxic cancer cell survival responses (Wilkinson and Ryan 2009; Wilkinson et al. 2009). Furthermore, the lack of p62/SQSTM1 removal in autophagy-deficient cells has been shown to be a contributing factor to tumor development (Mathew et al. 2009).

In short, autophagy is activated following metabolite deprivation and hypoxia, but also in response to a multitude of factors encountered during the development of cancer that perturb the equilibrated cellular environment. In addition, autophagy is also activated in response to a variety of chemotherapeutic drugs (Kondo et al. 2005). Thus, this draws us to the tentative conclusion that most, if not all, forms of stress stimulate autophagy, which when taken together has been termed the “integrated stress response” (Kroemer et al. 2010).

AUTOPHAGY—NOT JUST CELL AUTONOMOUS IN CANCER

Tumor cells are thought to favor metabolism of glucose via glycolysis, because they display high levels of glucose uptake and lactate production, even when oxygen is abundant. This form of aerobic glycolysis is termed the “Warburg Effect” (Warburg 1956). Tumor cells that fail to keep up with energy demands can die by necrosis, resulting in the production and accumulation of ROS (Lin et al. 2004). This induces oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment. As a result, bystander cells can switch on autophagy to remove ROS together with damaged cellular organelles, and tumor cells have hijacked this housekeeping program to fuel their own growth. Martinez-Outschoorn et al. (2011) showed that cancer cells transmit oxidative stress to neighboring fibroblasts to down-regulate Cav-1 (a marker often associated with early tumor recurrence, lymph node metastasis, and tamoxifen resistance). They also showed that cancer-associated fibroblasts are subsequently plagued with mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and aerobic glycolysis. They proposed that these stromal cells activate autophagy to remove damaged organelles, and the resulting degradation products are fed to tumor cells in a manner similar to what has been dubbed the “reverse Warburg effect” (Pavlides et al. 2009). Thus, not only is autophagy exploited intrinsically by cancer cells for their benefit, but also signals for autophagy activation are transmitted to the surrounding untransformed cells, and their activity is used to fuel tumor cell growth.

AUTOPHAGY: GUARDIAN OF THE GENOME IN ADDITION TO THE PROTEOME

Maintenance of genome integrity is critical to avoid tumorigenesis (Bartek et al. 2007). One of the main consequences of metabolic stress is the accumulation of ROS, which can cause DNA damage by inducing DNA base changes and strand breaks. This leads to the inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes and enhanced expression and/or activation of proto-oncogenes (Wiseman and Halliwell 1996). Consistently, ROS has long been associated with human cancer development (Wiseman and Halliwell 1996), and the role of autophagy in lowering ROS levels has been confirmed by many studies (Rouschop et al. 2009). Given that ROS stimulate autophagy, we can summarize that when ROS are present at high levels, autophagy is activated to scavenge ROS, thus preventing DNA damage and tumorigenesis.

Despite being more sensitive to metabolic stress, autophagy-deficient cancer cells are more likely to accumulate genomic damage. Mathew et al. (2007) showed that BECN1+/− and Atg5−/− immortalized baby mouse kidney (iBMK) cells accumulate higher levels of mutation, chromosomal instability, and accelerated progression into aneuploidy (Mathew et al. 2007). This finding is confirmed in an in vivo mammary model. When immortalized BECN1+/+ and BECN1+/− mouse mammary epithelial cells (iMMEC) were injected into mice to form xenografts, BECN1 hemizygosity resulted in genome damage under metabolic stress and gene amplification (Karantza-Wadsworth et al. 2007).

The role of autophagy as the guardian of the genome is multifaceted. The decision whether to die via apoptosis or necrosis, or to stay alive with unresolved damage, is not yet completely understood. These variations may be governed by the extent of damage, status of the affected cells, or the type of drug, which might also stimulate other responses apart from DNA damage. Either way, a defect in autophagy can be perceived as a road not only to impaired cytoplasmic homeostasis, but also to replication of cells containing DNA damage that may be predisposed to tumor development.

AUTOPHAGY PROGRAMS CELL DEATH

Apoptosis is long established as a form of programmed cell death and is known to be a key component of tumor suppression. The apoptotic pathways are well studied, and the role of autophagy in modulating apoptosis has been convincingly documented in vivo. Autophagy has been shown to be required for cell death in salivary glands during Drosophila development (Berry and Baehrecke 2007)—we refer the reader to the accompanying article in this collection by Das et al. (2012). Similarly, overexpression of wild-type Atg1 in Drosophila elicits a strong autophagic response, and cells that have high levels of this protein are selectively and rapidly eliminated (Scott et al. 2007).

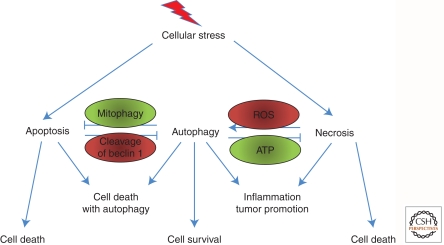

Although the exact mechanism(s) connecting autophagy and apoptosis as partners in cell killing is still unclear, the cross talk between autophagy and apoptosis has been dissected by many researchers (Fig. 3). Classical apoptotic regulators such as the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 have been shown to regulate autophagy, and, reciprocally, a cleaved form of the essential autophagy protein Atg5 has been shown to induce apoptosis directly at mitochondria (Pattingre et al. 2005; Yousefi et al. 2006).

Figure 3.

Autophagy and the control of cell death. There is cross talk between apoptosis and autophagy in the control of cell death. The two pathways also repress one another, fighting for either cell survival or cell death. Autophagy also regulates necrosis. Both pathways can regulate each other, and the products of inflammation can positively feed back to enhance the amplitude of these responses. Examples are shown to indicate how apoptosis and autophagy and necrosis and autophagy are connected.

The coactivation of autophagy and apoptosis has also been shown in cancer cells. For example, DRAM-1 was found to have both proautophagic and proapoptotic roles downstream from p53 (Crighton et al. 2006, 2007). Similarly, Yee et al. (2009) showed that another p53 target gene, the potent proapoptotic Puma, induces mitophagy and the subsequent release of cytochrome c, leading to apoptosis. The inhibition of PUMA-induced autophagy diminishes the apoptotic response, thus highlighting a synergy between autophagy and apoptosis in this cell death response.

Although apoptosis and autophagy can occur in a cooperative manner to elicit cell death, these processes are sometimes mutually antagonistic (Fig. 3) (Boya et al. 2005). For example, caspases (the effectors of the apoptotic cell death) have been shown to cleave and inactivate Atg6/Beclin 1, and the suppression of Atg6 function increases apoptotic cell death (Cho et al. 2009). These lines of evidence imply that apoptosis is either inhibited or delayed when autophagy is present, with the probable conclusion that autophagy is activated to protect cells from dying (Fig. 3).

Other contrasting behaviors between apoptosis and autophagy have been attributed to the status of the cell, or stage of transformation. Dominant-negative FADD invokes a death stimulus involving autophagy in healthy cells but not in cancer cells and induces varying amplitudes of death responses at different stages of cancer progression (Thorburn et al. 2005). In addition, oncogenic Ras has also recently been shown to cause autophagic cell death in the absence of apoptosis (Elgendy et al. 2011), even though other reports have indicated that autophagy is required for Ras-driven tumor growth (Guo et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2011).

These lines of evidence suggest that the decision to activate, repress, or simply not to manipulate autophagy, may be governed by the nature of the stimuli or the upstream regulator of an autophagic and/or apoptotic protein, as well as the health status of cells, and the net outcome of these three possibilities is either to promote or repress tumor survival, or both.

AUTOPHAGY AND NECROSIS

Necrosis is a form of cellular demise characterized by several features such as ATP depletion, the loss of cellular osmolarity, and release of various factors such as HMGB1 and cell lysis, which all lead to a strong inflammatory response (Edinger and Thompson 2004). Although necrosis is often perceived as an unregulated form of cell death, emerging evidence reveals that it can also occur as a form of caspase-independent programmed cell death and is specifically termed “necroptosis” (Vandenabeele et al. 2010). Programmed necrotic cell death is also known to be the mediator of cell death in response to certain classes of chemotherapeutic drugs (Zong et al. 2004).

As if contradicting the role of cell death in tumor suppression, necrosis is generally considered to be a tumor promoter and is often associated with poor prognosis (Swinson et al. 2002). Necrotic cells in vivo cause a strong inflammatory response, accompanied by the production of cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory enzymes, which can, in turn, positively feed back to cause further damage in surviving cells with enhanced tumorigenic potential (Balkwill et al. 2005).

Necrosis and autophagy, like apoptosis and autophagy, often occur coincidently (Fig. 3). Therapeutic treatment of cancer cells triggers necrosis due to bioenergetic compromise. Tumor cells can evade this ATP-limiting demise by activating the energy sensor LKB1/AMPK complex, which, in turn, inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), leading to activation of autophagy (Amaravadi and Thompson 2007). Although this seems to favor the viability of cancer cells, the major role for autophagy activation in promoting tumor development lies in the repression of necrosis-associated inflammatory responses. These responses can promote the release of prometastatic immune-modulatory factors such as HMBG1, and this may lead to increased metastasis (Thorburn et al. 2009a,b). Additionally, necrosis has been shown to be activated by AKT and Ras oncogenic signaling and is up-regulated when autophagy is compromised by monoallelic deletion of BECN1 (Degenhardt et al. 2006). Thus, autophagy is perceived to prevent necrosis in order to limit further cellular damage that may promote tumorigenesis and metastasis. However, the situation is not entirely straightforward because tumors that survive necrotic stress via autophagy could obtain an advantage to thrive under nutrient-limiting conditions and acquire mutations that cause resistance to cell death.

AUTOPHAGY AND SENESCENCE: A BARRIER TO TUMOR PROGRESSION?

Cellular senescence is a process in which cells enter a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). The permanent withdrawal from the cell cycle can restrict tumor cell proliferation and is therefore considered an important mechanism of tumor suppression. Senescent cells do, however, secrete a spectrum of proinflammatory cytokines, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), causing inflammation that is, in turn, a vector for tumor cell growth (Davalos et al. 2010).

Recently, Young et al. (2009) reported that several Atg genes—ULK3, Atg7, and LC3 (Atg8)—are up-regulated during oncogene-induced senescence. They also showed that autophagy is required for the transition of mitotic to senescent phase, and genetic ablation of autophagy delays the onset of senescence. Since then, much thought has been put into the “hows” and “whys” of the autophagy-regulated senescence program. Some researchers believe that autophagy is evoked to break down specific cellular components to enable physical remodelling associated with senescence (White and Lowe 2009). Additionally, autophagy may supplement senescent cells with the monomers that are required for the production and secretion of a plethora of growth factors, as well as for restructuring the cellular cytoskeleton (Adams 2009).

AUTOPHAGY AND TUMOR IMMUNITY

Cellular immunity can be generally classified into two categories; innate and adaptive. Innate immunity, analogous to the body’s first line of defense, is almost always engaged in triggering the complement system and inflammation. Adaptive immunity, on the other hand, results in a more specific and stronger response. This involves the surveillance, capture, and presentation of pathogens or pathogenic/non-self peptides by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages, B-cells, and dendritic cells (DCs), which then stimulate T-lymphocytes to invoke cell death, among other responses. Autophagy and immunity have long been considered as two inseparable entities (Schmid et al. 2007; Shoji-Kawata and Levine 2009). The roles of autophagy in regulating inflammation and adaptive immunity, ranging from lymphocyte development (Nedjic et al. 2008), pathogen recognition and destruction, to antigen presentation have been shown (Schmid et al. 2007).

Over the last few decades, neoplastic cells have been shown to express a panel of unique antigens that are recognized by T cells (Sensi and Anichini 2006). Hence, tumor antigen presentation is an important aspect of antitumor responses, and a defect in this system can result in tumor escape from immune surveillance—a facet often associated with cancer progression (Garcia-Lora et al. 2003; Hanahan and Weinberg 2011). DCs are one of the most effective professional APCs. One of the many contributors that impede DC function in tumor defense is the buildup of ROS, which are present abundantly in the tumor microenvironment (Fricke and Gabrilovich 2006). High levels of ROS have been shown to induce oxidative stress, resulting in JNK-mediated denditric cell death (Handley et al. 2005). Because autophagy has a major role in buffering ROS, a defect in this lysosomal degradation pathway would handicap DCs due to the accumulation of ROS.

Autophagy is also intrinsically connected to the process of antigen presentation. Classically, antigens derived from outside the cell are degraded in lysosomes, and autophagy has important roles in trafficking antigens destined for degradation, as well as trafficking peptides from degraded antigen back to the cell surface for presentation on the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Most tumor antigens are, of course, derived from within the cell, and degradation in this context is primarily via proteasomes, resulting in presentation on class I MHC. Autophagy, however, stills plays a major role in the presentation of tumor antigens on APCs directly on class II MHC or via a process termed “cross-presentation” on class I MHC (Munz 2010). With respect to this, priming of CD8+ T cells APCs presenting the melanocyte-derived tumor antigen gp100 is greatly enhanced when autophagy is pharmacologically induced in the melanocytes with rapamycin, and this is reversed when autophagy is blocked with 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (Li et al. 2008). The investigators also found that blocking autophagy at later stages by inhibiting autophagosome turnover facilitated antigen cross-presentation, subsequently revealing that autophagosomes are efficient transporters of antigen from antigen-presenting cells to T cells. This suggests that the stabilization of autophagosomes, rather than the initiation and completion of autophagy itself, is required for effective priming of cytotoxic T cells. Elegant in vivo studies by Lee et al. (2010) have confirmed that autophagy is particularly required to enhance class I antigen presentation by DCs. They showed that Atg5−/− DCs present antigen on class II molecules but have a reduced ability to activate CD4+ lymphocytes by promoting antigen degradation in autolysosomes. No differences were observed in DC migration or DC antigen capture via endocytosis and phagocytosis, as well as cross-presentation on class I. They also discovered that autophagy induced by starvation and rapamycin treatment decreases class II presentation.

Albeit varying in the mode of action, autophagy initiation is required for both class I and II MHC processing. Evidence indicates that the synthesis, but not degradation, of autophagosomes is the determining factor for class I, whereas for class II, both synthesis and degradation of autophagosomes are crucial (Dorfel et al. 2005). Aside from macroautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy has also been shown to play a role in antigen presentation, particularly in the presentation of endogenous antigen of cytoplasmic origin (Deretic 2005). It is conceivable, therefore, that more than one form of autophagy operates in antigen processing, and the dissection of this network, particularly in the context of tumor antigen presentation, may represent an encouraging step toward new, rationally designed tumor therapies.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Autophagy is not only a critical degradation process for housekeeping purposes in normal tissues, but it also affects various cellular mechanisms that are critical, or altered in cancer cells (Fig. 4). There may, however, be additional mechanisms relevant to tumor development where a role for autophagy is yet to be defined. For example, in addition to genetic alterations, cancer cells usually have tremendous changes in their epigenetic landscape (Sharma et al. 2010). Given that autophagosomes can sequester chromosomes (Sit et al. 1996) and autophagic breakdown of the nucleus is well documented in yeast (Kvam and Goldfarb 2007), it might be possible for autophagy to regulate epigenetic regulatory factors such as histone methyltransferases and deacetylases in the nucleus of mammalian cells. Could this be an additional role for autophagy in cancer?

Figure 4.

The contrasting roles of autophagy in cancer. Activating autophagy at different stages of cancer yields multiple opposing effects. In healthy cells, autophagy prevents cellular transformation by removing ROS and damaged mitochondria. However, following transformation, activation of autophagy can promote and suppress cancer progression, depending on the timing or stage of disease. Autophagy either mediates its effects directly or “communicates” with other cellular pathways such as senescence, apoptosis, necrosis, and inflammation.

It is a defining feature of cancer that tumor cells show uncontrolled proliferation compared with normal cells. Because autophagy is often deregulated in transformed cells, is there a link between autophagy and cell cycle deregulation? In this regard, autophagy has been reported to be activated in response to TGF-β, resulting in enhancement of TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Kiyono et al. 2009). Would this imply that autophagy could attenuate the cell cycle and limit cancer cell proliferation?

Because of these extensive links, autophagy is a very attractive target for cancer therapeutics. In fact, most existing drugs designed to kill cancer cells also induce autophagy (Kondo et al. 2005). Whether autophagy is activated to enhance cell killing or as a counterstress mechanism is governed by many factors, ranging from the nature of the stimulus to the health status of the cell. Recently, the role of autophagy in the interplay of stromal cells within the tumor niche has also been acknowledged (Martinez-Outschoorn et al. 2010, 2011). This adds another level of complexity to the existing theory whereby the induction of autophagy at different stages of cancer yields different effects (Fig. 4). With this knowledge, treatments, or at least adjuvants that modulate autophagy, could be incorporated into the cancer treatment regime (Amaravadi and Thompson 2007). Perhaps the delivery of autophagic modulators either positive or negative should also be tailored to the stage and type of cancer. In addition, would the modulation of autophagy be a strategy for both initial treatment and for treatment of relapsed disease?

These are all questions that remain to be answered. Nevertheless, the roles of autophagy in modulating various cellular processes involved in cancer progression are now without question. As a result, much excitement currently surrounds the possibility of targeting autophagy for tumor therapy. The issue, however, is not straightforward. As we have highlighted here, autophagy can have both positive and negative effects on tumor development, thus making it difficult to know whether to positively or negatively modulate autophagy in any given scenario. Moreover, it must be remembered that autophagy is not only serving to protect us against cancer, but also has major roles in protecting us against many other forms of disease (Ravikumar et al. 2010). Systemic modulation of autophagy, although beneficial for tumor therapy, may therefore have detrimental roles in normal tissues. Ultimately, however, with an optimistic view, it may be that transient modulation of autophagy may be sufficient for therapy without impact in normal tissues or that ways to selectively target tumor-associated autophagy may be devised. Numerous laboratories are currently addressing these issues, and the exciting answers should be revealed in the not-too-distant future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to those researchers whose studies on autophagy we were unable to cite because of the length of this article. We thank Simon Milling and members of the Tumour Cell Death Laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in the Tumour Cell Death Laboratory is supported by Cancer Research UK and the Association for International Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Editors: Eric H. Baehrecke, Douglas R. Green, Sally Kornbluth, and Guy S. Salvesen

Additional Perspectives on Cell Survival and Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Adams PD 2009. Healing and hurting: Molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol Cell 36: 2–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, Pincus DL, Yu W, Cayanis E, Kalachikov S, Gilliam TC, Levine B 1999. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics 59: 59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aki T, Yamaguchi K, Fujimiya T, Mizukami Y 2003. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase accelerates autophagic cell death during glucose deprivation in the rat cardiomyocyte-derived cell line H9c2. Oncogene 22: 8529–8535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi RK, Thompson CB 2007. The roles of therapy-induced autophagy and necrosis in cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res 13: 7271–7279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A 2005. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7: 211–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartek J, Bartkova J, Lukas J 2007. DNA damage signalling guards against activated oncogenes and tumour progression. Oncogene 26: 7773–7779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM 2009. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2570–2581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, Schuck S, Walter P 2007. ER-phagy: Selective autophagy of the endoplasmic reticulum. Autophagy 3: 285–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Baehrecke EH 2007. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell 131: 1137–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Metivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, et al. 2005. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 25: 1025–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, Jo YK, Hwang JJ, Lee YM, Roh SA, Kim JC 2009. Caspase-mediated cleavage of ATG6/Beclin-1 links apoptosis to autophagy in HeLa cells. Cancer Lett 274: 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A 2005. Proteolysis: From the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O’Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, Gasco M, Garrone O, Crook T, Ryan KM 2006. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 126: 121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D, Wilkinson S, Ryan KM 2007. DRAM links autophagy to p53 and programmed cell death. Autophagy 3: 72–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM 2004. Autophagy: In sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol 14: 70–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Das G, Shravage BV, Baehrecke EH 2012. Regulation and function of autophagy during cell survival and cell death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos AR, Coppe JP, Campisi J, Desprez PY 2010. Senescent cells as a source of inflammatory factors for tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 29: 273–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt K, Mathew R, Beaudoin B, Bray K, Anderson D, Chen G, Mukherjee C, Shi Y, Gelinas C, Fan Y, et al. 2006. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 10: 51–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V 2005. Autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol 26: 523–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele M, Maes H, Agostinis P 2010. ROS-mediated mechanisms of autophagy stimulation and their relevance in cancer therapy. Autophagy 6: 838–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfel D, Appel S, Grunebach F, Weck MM, Muller MR, Heine A, Brossart P 2005. Processing and presentation of HLA class I and II epitopes by dendritic cells after transfection with in vitro–transcribed MUC1 RNA. Blood 105: 3199–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger AL, Thompson CB 2004. Death by design: Apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy M, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Martin SJ 2011. Oncogenic ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell 42: 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen EL, Saftig P 2009. Autophagy: A lysosomal degradation pathway with a central role in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 664–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S 2005. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 8204–8209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke I, Gabrilovich DI 2006. Dendritic cells and tumor microenvironment: A dangerous liaison. Immunol Invest 35: 459–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta S, Hidaka E, Ogata A, Yokota S, Kamata T 2004. Ras is involved in the negative control of autophagy through the class I PI3-kinase. Oncogene 23: 3898–3904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F 2003. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol 195: 346–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, et al. 2011. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 25: 460–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144: 646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley ME, Thakker M, Pollara G, Chain BM, Katz DR 2005. JNK activation limits dendritic cell maturation in response to reactive oxygen species by the induction of apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 38: 1637–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MR, Kim MS, Oh JE, Kim YR, Song SY, Kim SS, Ahn CH, Yoo NJ, Lee SH 2009. Frameshift mutations of autophagy-related genes ATG2B, ATG5, ATG9B and ATG12 in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. J Pathol 217: 702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantza-Wadsworth V, Patel S, Kravchuk O, Chen G, Mathew R, Jin S, White E 2007. Autophagy mitigates metabolic stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 21: 1621–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Jeong EG, Ahn CH, Kim SS, Lee SH, Yoo NJ 2008. Frameshift mutation of UVRAG, an autophagy-related gene, in gastric carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol 39: 1059–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissova I, Deffieu M, Manon S, Camougrand N 2004. Uth1p is involved in the autophagic degradation of mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 39068–39074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono K, Suzuki HI, Matsuyama H, Morishita Y, Komuro A, Kano MR, Sugimoto K, Miyazono K 2009. Autophagy is activated by TGF-β and potentiates TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 69: 8844–8852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Lane JD 2010. Alternative macroautophagy. Autophagy 6: 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, Kondo S 2005. The role of autophagy in cancer development and response to therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 726–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneri K, Goi T, Hirono Y, Katayama K, Yamaguchi A 2007. Beclin 1 gene inhibits tumor growth in colon cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res 27: 1453–1457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Deplazes A, Sohrmann M, Peter M 2008. Mature ribosomes are selectively degraded upon starvation by an autophagy pathway requiring the Ubp3p/Bre5p ubiquitin protease. Nat Cell Biol 10: 602–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizhanovsky V, Xue W, Zender L, Yon M, Hernando E, Lowe SW 2008. Implications of cellular senescence in tissue damage response, tumor suppression, and stem cell biology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 73: 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B 2010. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 40: 280–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N 2004. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432: 1032–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam E, Goldfarb DS 2007. Nucleus–vacuole junctions and piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus in S. cerevisiae. Autophagy 3: 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Mattei LM, Steinberg BE, Alberts P, Lee YH, Chervonsky A, Mizushima N, Grinstein S, Iwasaki A 2010. In vivo requirement for Atg5 in antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity 32: 227–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters JJ 2005. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res 8: 3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang LX, Yang G, Hao F, Urba WJ, Hu HM 2008. Efficient cross-presentation depends on autophagy in tumor cells. Cancer Res 68: 6889–6895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, Levine B 1999. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 402: 672–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Choksi S, Shen HM, Yang QF, Hur GM, Kim YS, Tran JH, Nedospasov SA, Liu ZG 2004. Tumor necrosis factor–induced nonapoptotic cell death requires receptor-interacting protein-mediated cellular reactive oxygen species accumulation. J Biol Chem 279: 10822–10828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, Bauer DE, Kong M, Harris MH, Li C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB 2005a. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell 120: 237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB 2005b. Autophagy in metazoans: Cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri MC, Malik SA, Morselli E, Kepp O, Criollo A, Mouchel PL, Carnuccio R, Kroemer G 2009. Stimulation of autophagy by the p53 target gene Sestrin2. Cell Cycle 8: 1571–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Salvador-Montoliu N, Fueyo A, Knecht E, Mizushima N, Lopez-Otin C 2007. Tissue-specific autophagy alterations and increased tumorigenesis in mice deficient in Atg4C/autophagin-3. J Biol Chem 282: 18573–18583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM, Rivadeneira DB, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Wang C, Whitaker-Menezes D, Daumer KM, Lin Z, Witkiewicz AK, et al. 2010. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle 9: 3256–3276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Lin Z, Flomenberg N, Howell A, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP 2011. Cytokine production and inflammation drive autophagy in the tumor microenvironment: Role of stromal caveolin-1 as a key regulator. Cell Cycle 10: 1784–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, Chen G, Jin S, White E 2007. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev 21: 1367–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, et al. 2009. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell 137: 1062–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure NM, Pouyssegur J 2010. Hypoxia-induced autophagy: Cell death or cell survival? Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrpour M, Esclatine A, Beau I, Codogno P 2010. Overview of macroautophagy regulation in mammalian cells. Cell Res 20: 748–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Hatano M, Kobayashi Y, Kabeya Y, Suzuki K, Tokuhisa T, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T 2001. Dissection of autophagosome formation using Apg5-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol 152: 657–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ 2008. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451: 1069–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz C 2010. Antigen processing via autophagy—not only for MHC class II presentation anymore? Curr Opin Immunol 22: 89–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Young AR, Arakawa S, Samarajiwa SA, Nakashima T, Yoshida S, Hong S, Berry LS, Reichelt S, Ferreira M, et al. 2011. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science 332: 966–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedjic J, Aichinger M, Emmerich J, Mizushima N, Klein L 2008. Autophagy in thymic epithelium shapes the T-cell repertoire and is essential for tolerance. Nature 455: 396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, Komatsu M, Otsu K, Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S 2009. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461: 654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, Packer M, Schneider MD, Levine B 2005. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 122: 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Fortina P, Addya S, et al. 2009. The reverse Warburg effect: Aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle 8: 3984–4001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursiheimo JP, Rantanen K, Heikkinen PT, Johansen T, Jaakkola PM 2009. Hypoxia-activated autophagy accelerates degradation of SQSTM1/p62. Oncogene 28: 334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen EL, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, et al. 2003. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest 112: 1809–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, et al. 2010. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 90: 1383–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeldt MT, Ryan KM 2009. The role of autophagy in tumour development and cancer therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med 11: e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeldt MT, Ryan KM 2011. The multiple roles of autophagy in cancer. Carcinogenesis 32: 955–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouschop KM, Ramaekers CH, Schaaf MB, Keulers TG, Savelkouls KG, Lambin P, Koritzinsky M, Wouters BG 2009. Autophagy is required during cycling hypoxia to lower production of reactive oxygen species. Radiother Oncol 92: 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KM 2011. p53 and autophagy in cancer: Guardian of the genome meets guardian of the proteome. Eur J Cancer 47: 44–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Oku M, van der Klei IJ, Kiel JA 2006. Pexophagy: Autophagic degradation of peroxisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 1767–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlatti F, Maffei R, Beau I, Ghidoni R, Codogno P 2008. Non-canonical autophagy: An exception or an underestimated form of autophagy? Autophagy 4: 1083–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid D, Pypaert M, Munz C 2007. Antigen-loading compartments for major histocompatibility complex class II molecules continuously receive input from autophagosomes. Immunity 26: 79–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Juhasz G, Neufeld TP 2007. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol 17: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi M, Anichini A 2006. Unique tumor antigens: Evidence for immune control of genome integrity and immunogenic targets for T cell-mediated patient-specific immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 12: 5023–5032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA 2010. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis 31: 27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji-Kawata S, Levine B 2009. Autophagy, antiviral immunity, and viral countermeasures. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 1478–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit KH, Paramanantham R, Bay BH, Chan HL, Wong KP, Thong P, Watt F 1996. Sequestration of mitotic (M-phase) chromosomes in autophagosomes: Mitotic programmed cell death in human Chang liver cells induced by an OH* burst from vanadyl(4). Anat Rec 245: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger-Barraissoul S, Rami A 2009. Serum deprivation induced autophagy and predominantly an AIF-dependent apoptosis in hippocampal HT22 neurons. Apoptosis 14: 1274–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson DE, Jones JL, Richardson D, Cox G, Edwards JG, O’Byrne KJ 2002. Tumour necrosis is an independent prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: Correlation with biological variables. Lung Cancer 37: 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y, Liang C, Jung JU, Cheng JQ, Mule JJ, et al. 2007. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1142–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S, Eishi Y, Hino O, Tanaka K, Mizushima N 2011. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev 25: 795–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Djavaheri-Mergny M, D’Amelio M, Criollo A, Morselli E, Zhu C, Harper F, et al. 2008. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat Cell Biol 10: 676–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn J, Moore F, Rao A, Barclay WW, Thomas LR, Grant KW, Cramer SD, Thorburn A 2005. Selective inactivation of a Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD)–dependent apoptosis and autophagy pathway in immortal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 16: 1189–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn J, Frankel AE, Thorburn A 2009a. Regulation of HMGB1 release by autophagy. Autophagy 5: 247–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn J, Horita H, Redzic J, Hansen K, Frankel AE, Thorburn A 2009b. Autophagy regulates selective HMGB1 release in tumor cells that are destined to die. Cell Death Differ 16: 175–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T, Kroemer G 2010. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: An ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 700–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O 1956. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 123: 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E, Lowe SW 2009. Eating to exit: Autophagy-enabled senescence revealed. Genes Dev 23: 784–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Ryan KM 2009. Growth factor signaling permits hypoxia-induced autophagy by a HIF1α-dependent, BNIP3/3L-independent transcriptional program in human cancer cells. Autophagy 5: 1068–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, O’Prey J, Fricker M, Ryan KM 2009. Hypoxia-selective macroautophagy and cell survival signaled by autocrine PDGFR activity. Genes Dev 23: 1283–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman H, Halliwell B 1996. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: Role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem J 313: 17–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Klionsky DJ 2007. Autophagosome formation: Core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol 9: 1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, Bause A, Li Y, Stommel JM, Dell’antonio G, et al. 2011. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev 25: 717–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee KS, Wilkinson S, James J, Ryan KM, Vousden KH 2009. PUMA- and Bax-induced autophagy contributes to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 16: 1135–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AR, Narita M, Ferreira M, Kirschner K, Sadaie M, Darot JF, Tavare S, Arakawa S, Shimizu S, Watt FM 2009. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev 23: 798–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, Ziemiecki A, Schaffner T, Scapozza L, Brunner T, Simon HU 2006. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol 8: 1124–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N 2003. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 15077–15082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL 2008. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 283: 10892–10903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zong WX, Ditsworth D, Bauer DE, Wang ZQ, Thompson CB 2004. Alkylating DNA damage stimulates a regulated form of necrotic cell death. Genes Dev 18: 1272–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]