Abstract

Aggression between partners represents a potential guiding force in family dynamics. However, research examining the influence of partner aggression (physically and psychologically aggressive acts by both partners) on harsh parenting and young child adjustment has been limited by a frequent focus on low risk samples and by the examination of partner aggression at a single time point. Especially in the context of multiple risk factors and around transitions such as childbirth, partner aggression might be better understood as a dynamic process. In the present study, longitudinal trajectories of partner aggression from birth to age 3 years in a large, high-risk, and ethnically diverse sample (N = 461) were examined. Specific risk factors were tested as predictors of aggression over time, and the longitudinal effects of partner aggression on maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment were examined. Partner aggression decreased over time, with higher maternal depression and lower maternal age predicting greater decreases in partner aggression. While taking into account contextual and psychosocial risk factors, higher partner aggression measured at birth and a smaller decrease over time independently predicted higher levels of maternal harsh parenting at age 3 years. Initial level of partner aggression and change over time predicted child maladjustment indirectly (via maternal harsh parenting). The implications of understanding change in partner aggression over time as a path to harsh parenting and young children's maladjustment in the context of multiple risk factors are discussed.

Keywords: Partner aggression, multiple risk factors, longitudinal modeling, early childhood, harsh parenting

The partner relationship has been conceptualized as a guiding force in family dynamics (Rossman, 1986). Aggression between partners (partner aggression), including physical and psychological forms, is highly prevalent among young couples with at-risk characteristics (Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008). Research has consistently indicated that both forms of partner aggression are positively associated with harsh parenting and child maladjustment, including internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Although the literature has moved toward an increasingly nuanced understanding of the role of partner aggression in influencing parenting and child outcomes (Cummings & Davies, 2002, 2010), this work has been limited by a preponderance of low-risk, middle-class samples (Cummings & Davies, 2002) and the examination of partner aggression as a static process in cross-sectional research (Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Lekka, 2007; Levendosky, Huth-Bocks, Semel, & Shapiro, 2002). Multiple sources of contextual and psychosocial stress in high-risk families might contribute to volatility in partner aggression. However, our understanding of changes in partner aggression during a child's early life and how such changes affect parenting behavior and child adjustment remains limited.

Research on trajectories of partner aggression in high-risk families has the potential to create a better understanding of the role of partner aggression in families with the greatest need for intervention and prevention services. A focus on birth through toddlerhood is particularly important as fluctuations in partner aggression are often expected during such transitional periods (Martin, Mackie, Kupper, Buescher, & Moracco, 2001), and interventions will likely have the most impact during these early stages of child development (Gunnar, Fisher, & Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network, 2006). In the present study, we sought to examine trajectories of partner aggression (from birth to age 3 years) and their role in predicting maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment in a large, high-risk, and ethnically diverse sample of mothers. The mothers were characterized as high risk based on an initial screening for indicators of contextual and psychosocial adversity at childbirth (Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly, & Landsverk, 2010). Physical and psychological aggression between partners were included: both types of aggression are highly prevalent and frequently co-occur in young high-risk couples (e.g., Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Capaldi, Dishion, Stoolmiller, & Yoerger, 2001), with psychological aggression typically preceding most types of physical aggression (O'Leary, Malone, & Tyree, 1994).

Partner aggression in the present study refers to maternal reports of aggression toward (perpetration) and from (victimization) a partner at each time point. Although perpetration alone might be informative, the results from recent developmental studies have consistently suggested that both partners’ aggression is significantly correlated within the couple (Slep & O'Leary, 2005). In addition, recent findings suggest that child emotional security and internalizing and externalizing symptomatology are similarly related to aggression against mothers and fathers (El-Sheikh, Cummings, Kouros, Elmore-Staton, & Buckhalt, 2008).

Changes in Partner Aggression in High-Risk Families

The findings from longitudinal research on partner aggression indicate substantial change across time. Levels of partner aggression have been found to decrease over time (Kim et al., 2008), with partners with the highest initial levels of aggression demonstrating the greatest changes (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007). In particular, the results from large, multistate studies suggest that the prevalence of partner aggression declines significantly over the transition to parenthood (Martin et al., 2001; Saltzman, Johnson, Gilbert, & Goodwin, 2003). Others have noted that partner aggression increases in the 1st postnatal month but declines over the next 5 months (Macy, Martin, Kupper, Casanueva, & Guo, 2007). These results suggest that partner aggression should be understood as a dynamic or frequently changing process, particularly around transitions such as childbirth, and that a decline in partner aggression might be expected around this period. However, little work has been done to characterize trajectories of partner aggression in high-risk families with limited resources: those who might experience higher levels of stress after childbirth and over the early years of parenting.

Previous evidence about changes in partner dynamics following childbirth indicates a high level of heterogeneity, with socioemotional and demographic factors explaining differences in trajectories over time (Belsky & Rovine, 1990). High-risk families often face multiple psychosocial and contextual risk factors that might be relevant for determining the course of partner aggression. Early social experiences, especially with caregivers, appear to play a large role in shaping adult intimate partner relationships (Ehrensaft, 2009). For example, a history of childhood abuse predicts a greater likelihood of partner aggression over the transition to parenthood (Wilson et al., 1996). This transmission of aggression from early experiences to the partner relationship might result from expectations about intimate relationships and from the effects of stressful early life experiences on regulatory capacity (Ehrensaft, 2009). As such, difficulties regulating emotions, as evidenced by maternal depression, violent behavior, and severe psychopathology or criminality, appear to contribute to partner aggression during potentially stressful times, including the transition to parenthood (Cox, Paley, Burchinal, & Payne, 1999; Wilson et al., 1996).

Parental demographic factors, including age and ethnicity, might also predict trajectories of partner aggression over time due to effects on regulatory capacity and cultural expectations about intimate relationships. Previous evidence supports the importance of demographic factors such as age in explaining trajectories of change in the partner relationship over the transition to parenthood (Belsky & Rovine, 1990), and this might be particularly true for high-risk, diverse samples. Those who are young might be less prepared to handle the challenges of partnering and childrearing, leading to higher levels of dysregulated and aggressive interactions (Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). However, the role of age in predicting partner aggression during early child rearing is unclear; most research on this topic has focused on a limited time period immediately surrounding pregnancy (Saltzman et al., 2003).

In terms of ethnicity, the research findings have been equivocal and, at times, contradictory. For example, researchers have alternatively suggested that being Hispanic predicts higher or lower levels of aggression during pregnancy (Jasinski, 2004). A greater emphasis on family in Mexican American culture might serve as a protective factor for the partner relationship (Bulanda & Brown, 2007), with contradictory findings stemming from the confounding effects of ethnicity and SES (Jasinski, 2004). In the present study, we examined the relative importance of these risk factors for trajectories of partner aggression in high-risk families from birth to age 3 years.

Partner Aggression and Harsh Parenting Practices

Strong associations between partner aggression and parental harsh discipline have been established in the literature (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Partner physical aggression appears to co-occur with parent–child physical aggression in approximately 40% of families (Slep & O'Leary, 2005). According to the spillover hypothesis, negative affect in the partner relationship, might carry over into the parent–child relationship (Erel & Burman, 1995). Recent findings suggest that heightened stress reactivity to negative partner dynamics (indexed by the stress hormone, cortisol) mediates between partner dynamics and parenting practices (Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti, & Cummings, 2009). Sturge-Apple et al. hypothesized that the hormonal substrates of the stress response system, activated by negative partner dynamics, influence functioning in brain regions involved in emotional and cognitive processing, creating a negative bias in attending and responding to child behavior. Despite bidirectional influences between the partner and parent–child relationships, the effects of partner aggression on the parent–child relationship might be particularly salient when the child is young and the parent–child relationship is emerging. For instance, in a longitudinal study, Frosch, Mangelsdorf, and McHale (2000) reported that partner conflict at age 6 months predicted hostile parenting behaviors at age 3 years, which, in turn, predicted insecure attachment. Partner aggression has also been found to negatively influence a mother's internal representations of her child and her caregiving, which, in turn, influence parenting behavior (Huth-Bocks, Levendosky, Bogat, & von Eye, 2004). Consistent with these findings, higher levels of partner conflict and hostility during the prenatal period predict higher levels of physical punishment during early childhood (Kanoy, Ulku-Steiner, Cox, & Burchinal, 2003).

However, it remains unclear how changing levels of partner aggression are associated with harsh parenting practices, particularly for high-risk families. Examining this link in the presence of maternal contextual and psychosocial risk factors could shed light on hypotheses regarding associations between partner aggression and harsh parenting. For example, according to the spillover hypothesis, increases in partner aggression will predict increases in harsh parenting as negative affect carries over from one relationship to the other (Erel & Burman, 1995). Extrapolating from the work of Sturge-Apple et al. (2009), continued engagement in aggressive dynamics would lead to repeated episodes of stress reactivity over time, potentially causing greater negative biasing of emotional and cognitive responses to children. However, if high initial levels of partner aggression lead to a lasting change in stress reactivity or emotional and cognitive processing, the subsequent changes in partner aggression might not be as important for understanding harsh parenting. Moreover, in a high-risk sample facing multiple other challenges likely to affect stress reactivity and processing biases, changes in partner aggression might have a more limited impact harsh parenting levels.

Partner Aggression Over Time and Young Children's Adjustment in High-Risk Families

In addition to its implications for parenting, partner aggression appears to impact child adjustment more directly through child emotional and cognitive responses to witnessing aggression (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Grych & Fincham, 1990). The potential for direct effects of exposure to partner aggression exists even during the 1st year of life as infants discriminate between different emotional states and demonstrate greater arousal in response to anger (Grossmann, Striano, & Friederici, 2005). Researchers have demonstrated associations between partner aggression and indices of emotional development in 6-month-olds (Crockenberg et al., 2007) and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in preschoolers (Levendosky et al., 2002).

Some associations have been found between partner aggression and young child adjustment in longitudinal studies. For example, Ingoldsby, Shaw, Owens, and Winslow (1999) reported that partner aggression predicted boys’ psychosocial maladjustment concurrently and over time across ages 2–5 years; high levels of aggression at one or two time points predicted higher internalizing and externalizing behavior compared to low aggression at both time points. However, the relative contributions of the initial level of aggression and changes in aggression over the early years of childrearing in high-risk families have not been fully explicated. Children exposed to multiple risk factors might experience more acute feelings of insecurity and maladjustment when facing partner aggression. Alternatively, in the presence of multiple risk factors, partner aggression might be a less potent threat. Previous research findings with at-risk families in studies in which other risk factors have not been controlled make it difficult to pinpoint the unique effects of partner aggression (Ingoldsby et al., 1999; Levendosky et al., 2002).

The Present Study

In the present study, we examined trajectories of partner aggression (from birth to age 3 years) and their association with maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment, taking into account the mothers’ contextual and psychosocial adversity. First, we examined longitudinal trajectories of partner aggression in a large, ethnically diverse sample of high-risk mothers. Given their risk profile, we expected high initial levels of partner aggression. Based on previous research (e.g., Martin et al., 2001), we expected a general decline in partner aggression levels after childbirth; however, due to the high-risk nature of the sample, we anticipated potential increases in partner aggression in toddlerhood, when children present new parenting challenges.

Second, we expected variability in trajectories of aggression and examined several psychosocial and contextual risk factors, including maternal age at birth, ethnicity, history of abuse, history of criminality and psychopathology, depression, and potential for violence, as predictors of such variability in partner aggression over time. Based on prior research findings (e.g., Ehrensaft, 2009; Wilson et al., 1996), we hypothesized that all of these factors, with the exception of ethnicity, would predict higher levels of partner aggression initially and over time. We did not specify hypotheses regarding ethnicity due to mixed findings in this area.

Third, to investigate whether trajectories of partner aggression relate to maternal harsh parenting and to child maladjustment, we examined the extent to which the initial level of and change in partner aggression across the first 3 years of life predicted maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment at age 3 in the presence of multiple risk factors. We hypothesized that higher initial levels of and increases in partner aggression would predict higher levels of harsh parenting at age 3 (Kanoy et al., 2003), which would, in turn, relate to higher levels of child maladjustment at age 3. In line with the literature suggesting direct effects of partner aggression on young child adjustment, we also expected that consistently high levels of partner aggression across time would independently predict to higher levels of child maladjustment at age 3.

Method

Participants

Data for the present study came from a sample of 488 at-risk mothers recruited at childbirth at a single hospital for the Healthy Families America–San Diego Clinical Trial (February 1996–March 1997). The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center in San Diego. The research staff members identified at-risk families via hospital computer systems. The mothers who met study eligibility criteria (i.e., residing in the target area, nonmilitary, and English or Spanish speaking) were screened for 15 risk factors from the Hawaii Risk Indicators checklist (Hawaii Family Stress Center, 1994). Any mother who endorsed two or more risk factors or who was not married, received inadequate prenatal care, or had attempted to have an abortion was further assessed using the Kempe Family Stress Checklist (Kempe & Kempe, 1976). This 10-item, semistructured interview, assesses risk for child abuse. Items were rated on an 11-point scale: 0 (not problematic) to 10 (severely problematic); any mother who scored 25 or greater and did not have an open case with child protective services was invited to participate. Trained research interviewers conducted annual assessments of the mothers and children in the home at Time 1 (within 2 weeks of birth) and Times 2, 3, and 4 (ages 1, 2, and 3 years). About 20% of the families requested Spanish-speaking interviewers.

The analyses conducted for this study included all women who reported having a partner at any assessment time point (N = 461). Maternal age ranged 14–42 years (M = 23.3, SD = 5.99), with 54.7% of the mothers having not completed high school or a high school equivalency test. The ethnicity breakdown was as follows: 24.7% Caucasian, 27.1% English-speaking Hispanic, 19.5% African American, 19.3% Spanish-speaking Hispanic, and 9.3% Asian American or other. The median category for gross annual household income was $10,000–$10,999, based on an 18-point scale: 1 (less than $2,000 per year) to 18 ($50,000 or more per year). The percentages of mothers with partners at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 72.0%, 72.7%, 62.7%, and 61.0%, respectively. The retention rates at Times 2, 3, and 4 were 89%, 82.6%, and 82.8%, respectively. There were no significant differences between the mothers who remained in the study or dropped out of the study on any of the screening items, major demographic characteristics, or Time 1 variables. There was one significant difference on these variables between the participating mothers and the mothers who were excluded for not having had a partner during the study: The excluded mothers reported lower gross annual household income (Mdn = $8,000–8,999).

Measures

The measures in this study were administered in English or Spanish. At the time of data collection, there were no existing Spanish translations for the measures of interest, so each measure was translated by a bilingual Mexican American translator from the region in which the study took place. Internal consistency remained high for all measures in both languages. Therefore, internal consistency for each measure is reported only for the overall sample.

Maternal age

Mothers’ chronological age was used in the study.

Maternal ethnicity

Hispanic ethnicity was coded as 1, and non-Hispanic ethnicity was coded as 0. Approximately half of the sample (46.4%) reported being Hispanic.

Maternal potential for violence and history of criminality and psychopathology

We used two items from the Kempe Family Stress Checklist, the semistructured interview conducted with mothers during the initial screening procedure (just prior to Time 1), to assess maternal potential for violence and history of criminality and psychopathology. Maternal history of criminality and psychopathology was rated as follows: 0 (lack of arrests, drug use, and psychiatric care) to 10 (recent time in prison, chronic drug use, or severe psychopathology, such as psychosis). Maternal potential for violence was rated as follows: 0 (yelling when angry) to 10 (fear of losing control or damaging the house or current/historical use of violence against others). High inter-rater reliability (.93) and good predictive validity have been documented for the Kempe Family Stress Checklist (see Korfmacher, 2000). In this sample, approximately 57% of the mothers indicated moderate to severe histories of criminality and psychopathology, whereas 22% of them indicated moderate to severe potential for violence. These items were log transformed due to positive skew.

Maternal history of abuse

At Time 4, we used an adapted version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) to assess maternal emotional and physical abuse during childhood. The items were reworded to focus on experiences of aggression from a parent or caregiver before the age of 18, and only items relevant to parent–child aggression were included. We included frequencies for three items constituting emotional abuse (e.g., cursing and derogatory name calling) and eight items constituting physical abuse (e.g., hitting and burning/scalding). Response categories were recoded to reduce skew: 0 (none), 1 (1–2 times), 3 (3–5 times), 6 (6–10 times), 11 (11–20 times), or 20 (more than 20 times). Internal reliabilities were .80 and .87 for emotional and physical abuse, respectively. The scales were significantly correlated at .76, p < .001, and were thus combined for analysis. Approximately half of mothers (47.5%) reported childhood abuse history. The mean composite scores ranged 0–5 (M = .64, SD = 1.05). This score was log transformed due to positive skew.

Maternal depression

We used the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) to assess Time 1 maternal depression. The mothers reported about the past week on a 4-point scale: 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). The scores ranged 0–45 (M = 17.0, SD = 9.96), with approximately half of mothers (48.5%) scoring at or above the clinical cutoff of 16. Internal reliability of this scale has been found to be high (.90; Radloff, 1977) and was over .80 in the present study.

Maternal partner relationships

At Times 1–4, each mother reported whether she was in a partner relationship: 35.8% at all time points, 23.2% at three time points, 22.6% at two time points, and 18.4% at one time point. This variable was included in the analyses to control for the potential effects of varying numbers of data points due to changes in relationship status over time.

Partner aggression

We administered the CTS at Time 1 and the CTS2 (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) at Times 2–4 to assess partner aggression in the past 12 months. Maternal report on the CTS at a particular time point was only included in the analyses if the mother had a current partner at that time point. To create a consistent measure for longitudinal modeling, we dropped items that were unique to either version (one psychological aggression item from each version). We also averaged two items from the CTS2 that were included on the CTS as one item. Maternal aggression toward and from her partner were therefore rated using four items from the Psychological Aggression subscale and seven items from the Physical Assault subscale rated as follows: 0 (this has never happened), 1 (once), 2 (twice), 3 (3–5 times), 4 (6–10 times), 5 (11–20 times), 6 (more than 20 times), or 7 (occurred only prior to the past year). Based on Straus et al.'s suggestion, responses involving a range of frequency were recoded to a midpoint to compute annual frequencies of partner aggression (e.g. 8 [6–10 times] and 15 [11–20 times]), and response 6 was recoded to 25. Response 7 was recoded as 0 due to the yearly assessments in the present study. Maternal aggression and partner aggression were significantly correlated at each time point, r = .72–.87, p < .01 (psychological aggression), and r = .38–.68, p < .01 (physical aggression), and were averaged to create composite physical and psychological aggression scores. The correlation for physical aggression between partners at T2 was slightly lower (r = .38, p < .01) than for the other time points. However, given our focus on the dynamics of partner aggression within the family that might impact parenting and child adjustment, we included both partners’ aggression to capture the overall level in the home.

The prevalence of reported psychological aggression was 86.90%, 49.80%, 43.30%, and 38.85% at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The prevalence of reported physical aggression was 43.15%, 25.25%, 17.45%, and 10.40% at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4. Physical and psychological aggression (as measured by the CTS) have previously been found to load onto a common latent construct of relationship aggression (El-Sheikh et al., 2008). In the present study, physical and psychological aggression were strongly correlated at each time point, r = .40–.54, p < .01, and were averaged to create a composite partner aggression score used in analyses. They were not weighted differently in the composite as previous findings in a high-risk community sample have shown that the percentage of variance in child behavior problems explained by physical and psychological aggression is similar (Jouriles, Norwood, & McDonald, 1996). Other researchers have argued for the ecological validity of including both psychological and physical aggression in the assessment of partner aggression relevant for child outcome (El-Sheikh et al., 2008). Internal reliabilities for the CTS2 have been found to range between .79 and .95 (Straus et al., 1996). In our study, internal reliabilities for the combined physical and psychological abuse scales ranged .89–.91 across time. The means were 3.01 (SD = 3.27), 1.64 (SD = 1.99), 1.39 (SD = 2.12), and 1.07 (SD = 1.82) at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The composite score was log transformed due to positive skew.

Maternal harsh parenting

We administered a modified version of the Parent–Child CTS (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) to assess Time 4 maternal harsh parenting. We included summed scores across 16 items: 5 from the Psychological Aggression subscale and 11 from the Physical Assault subscale. The response scale was as follows: 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times) or 7 (occurred only prior to the past year). Responses were recoded in the same manner as for the partner aggression measure. Consistent with the literature, psychological and physical aggression were highly correlated, r = .53, p < .001, and were combined to form a composite maternal harsh parenting score (Chronbach α = .76). Internal consistency of these two scales has previously been reported to be between .55 and .60 (Straus et al., 1998). The prevalence of any maternal harsh parenting was 87.5%. The mean for maternal harsh parenting was 1.04 (SD = 1.34). This composite score was log transformed due to positive skew.

Child maladjustment

We administered the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 (CBCL; Achenbach, 1992) to mothers at Time 4 to assess the two “broadband” factors yielded by this measure: child internalizing and externalizing behavior. The mothers scored the frequency of each item on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true) to 2 (always true). Reliability for the internalizing and externalizing scales in the present sample was high (.88 for each subscale). The mean internalizing and externalizing total scores were 9.16 (SD = 5.75) and 12.49 (SD = 7.46), respectively. Further, 22.4% and 18.9% of the sample had t-scores of 60 or higher (at or above the 84th percentile) for internalizing and externalizing, respectively. Due to high correlations between the scales, r = .70, p < .00, they were averaged to form a composite.

Analysis Plan

After the initial descriptive analysis (see Table 1 for correlations between study variables), our analyses involved three steps to examine the longitudinal trajectory of partner aggression (Times 1–4) using LGC modeling. Maternal ratings of partner aggression on the CTS were used to estimate two latent growth factors (intercept and slope). As described above, only partner aggression ratings for mothers with current partners were included at each time point because the growth model accommodates missing data. The intercept factor was centered at Time 1 to indicate the estimated level of partner aggression reported within 2 weeks of childbirth. The slope factor indicated the estimated direction and magnitude of change in partner aggression from birth to age 3. First, we fitted the unconditional LGC model to examine the average sample trend and individual differences in aggression over time. Second, we added the hypothesized Time 1 predictors to examine associations with the intercept and slope factors of partner aggression. Third, we added Time 4 maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment as outcome measures, testing direct and indirect (via maternal harsh parenting) effects of partner aggression on child maladjustment. All analyses were done using Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Major Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time 1 partner aggression | — | |||||||||||

| 2. Time 2 partner aggression | .44*** | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Time 3 partner aggression | .41*** | .51*** | — | |||||||||

| 4. Time 4 partner aggression | .26*** | .37*** | .67*** | — | ||||||||

| 5. Time points with partner | –.03 | -.04 | .01 | .09 | — | |||||||

| 6. Maternal age | –.10* | .03 | –.01 | .07 | .01 | — | ||||||

| 7. Maternal ethnicity | –.14** | –.17** | –.21** | –.06 | –.01 | –.10* | — | |||||

| 8. History psychopathology | .28*** | .20*** | .25*** | .20** | .03 | .01 | –.31*** | — | ||||

| 9. Maternal history of abuse | .21*** | .10 | .24** | .26*** | –.08 | .10 | –.12* | .20*** | — | |||

| 10. CESD | .20*** | .11* | .03 | .05 | –.13** | .01 | .03 | –.06 | .14** | — | ||

| 11. Potential for violence | .22*** | .18** | .18** | .06 | –.15** | .03 | –.10* | .17*** | .03 | .06 | — | |

| 12. Harsh parenting T4 | .16** | .25*** | .40*** | .50*** | –.08 | .09 | -.17** | .16** | .34*** | .05 | .01 | — |

| 13. CBCL T4 | .03 | –.04 | .07 | .15* | .03 | –.03 | –.05 | .02 | .20*** | .20*** | .01 | .23*** |

Note. CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. Spearman's p was used for any correlation involving a nonparametric variable.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results

Unconditional Growth Model of Partner Aggression

As indicated from the means reported above, partner aggression stabilized after Time 2, suggesting that the overall trend from birth through age 3 years might not be linear. In fact, the LGC model, in which the intercept factor loadings were all fixed at 1 and the slope factor loadings were fixed at 0, 1, 2, and 3 (Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively), did not fit the data well, χ2 (5) = 26.75, p = .00, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .10. To accommodate potential nonlinearity for some individuals, a linear spline model was fitted (see Stoolmiller, 1995). The linear spline model has been used in longitudinal studies as an effective way to approximate nonlinearity in data, especially when there are only 3–4 time points (e.g., Kim et al., 2010). In this model, the intercept factor loadings were all fixed at 1, and the slope factor loadings were fixed at 0 (Time 1) and 1 (Time 4); the Times 2 and 3 slope factor loadings were freely estimated. This model had a significantly better fit, χ2 (3) = 7.65, p = .06, CFI = .98, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .06. By freeing two parameters, the chi-square statistic was reduced from 26.75 to 7.65, nested χ2 = 19.1, df = 2, p < .00, indicating a significant improvement in fit; thus, the linear spline model was used in the remaining analyses.

The means of the intercept and slope factor in the unconditional linear spline model were .48, p < .00, and –.25, p < .00, respectively, indicating that both were significantly different from 0. These values represented the average initial levels and growth rates across all individuals (i.e., group means). The negative slope factor mean indicated that, on average, there were significant decreases in partner aggression over time. The intercept and slope factor had variances of .06, p < .00, and .07, p < .00, respectively, indicating substantial individual differences in the initial levels and in growth rates of aggression. The significant negative correlation between the intercept and slope factor –.042, p < .00, suggests that higher Time 1 partner aggression predicted a greater decrease in aggression over time.

Factors Predicting Growth in Partner Aggression Over Time

Time 1 maternal age, ethnicity, history of abuse, history of criminality and psychopathology, depression, and potential for violence were tested as predictors of the intercept and slope. Covariances between predictors evidencing significant bivariate correlations and between the intercept and the slope factor were included. The model fit the data well, χ2 = 29.20, df = 22, p = .14, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .03. The means of the intercept and slope factor in the conditional linear spline model were .43, p < .00, and –.33, p < .00, respectively. The intercept and slope factor variances, .05, p < .00, and .06, p < .00, respectively, indicated significant individual variance even in the presence of the predictors. Significant covariance between the intercept and slope factor was still observed.

There were significant positive effects of maternal history of abuse, history of criminality and psychopathology, depression, and potential for violence on the intercept factor (see Table 2, Model 1). Maternal age was negatively associated with the intercept factor, suggesting that older mothers tended to report less Time 1 partner aggression. Maternal depression and potential for violence evidenced significant negative associations with the slope factor, indicating that they predicted greater decreases in partner aggression over time. Maternal age had a significant positive association with the slope factor, suggesting that older mothers tended to report smaller decreases in partner aggression over time. The trajectory process and the predictors explained 65%, 45%, 60%, and 71% of the variance in partner aggression at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The predictors accounted for 27% of the variance in the intercept, p < .00, and 11% of the variance in the slope, p < .05, of partner aggression.

Table 2.

Linear Spline Model with Predictors Only (Model 1) and with Outcomes (Model 2)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Interparental aggression intercept mean | 0.43*** | 0.07 | 0.42*** | 0.07 |

| Interparental aggression intercept variance | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 0.05 *** | 0.01 |

| Intercept covariance with slope | –0.04** | 0.01 | –0.03** | 0.01 |

| Predictors of intercept | ||||

| Maternal age | -0.07** | 0.02 | –0.07** | 0.02 |

| Maternal ethnicity | –0.04 | 0.03 | –0.05 | 0.03 |

| CESD | 0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.06*** | 0.01 |

| Potential for violence | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.14*** | 0.04 |

| Maternal abuse history | 0.19* | 0.07 | 0.17* | 0.07 |

| History psychopathology | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.03 |

| Interparental aggression slope mean | –0.33*** | 0.09 | –0.30** | 0.09 |

| Interparental aggression slope variance | 0.06*** | 0.02 | 0.06*** | 0.01 |

| Predictors of slope | ||||

| Maternal age | 0.09** | 0.03 | 0.08* | 0.03 |

| Maternal ethnicity | –0.00 | 0.04 | –0.01 | 0.04 |

| CESD | –0.05* | 0.02 | –0.05* | 0.02 |

| Potential for violence | –0.10* | 0.05 | –0.09 | 0.05 |

| Maternal abuse history | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| History psychopathology | –0.07 | 0.04 | –0.08 | 0.04 |

| Outcomes with intercept | ||||

| Maternal harsh parenting | 0.46*** | 0.08 | ||

| Child maladjustment | –1.60 | 2.25 | ||

| Outcomes with slope | ||||

| Maternal harsh parenting | 0.56*** | 0.08 | ||

| Child maladjustment | –0.22 | 2.70 | ||

| Outcome with maternal harsh parenting | ||||

| Child maladjustment | 5.43** | 2.04 | ||

Note. CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale. Unstandardized estimates are presented. Control variables for maternal harsh parenting included number of time points with a partner and maternal age, ethnicity, depression, potential for violence, and histories of abuse, criminality, and psychopathology. Only number of time points with a partner and maternal history of abuse significantly predicted maternal harsh parenting, and did so in opposite directions –.02, .01, p < .05, and .20, .05, p < .001, respectively. Covariates with child maladjustment included maternal history of abuse and depression, which both predicted higher levels of maladjustment, .22, .07, p < .01, and 1.28, .32, p < .000, respectively.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

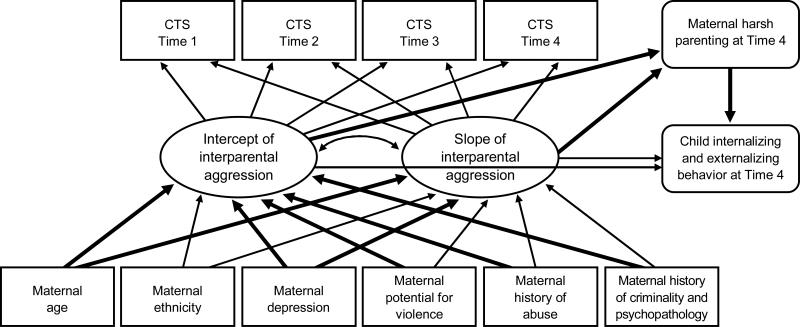

Growth in Partner Aggression, Maternal Harsh Parenting, and Child Maladjustment

As described above, maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment at Time 4 were then included in the model as outcome variables, with the intercept and slope factor of partner aggression predicting directly to maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment and indirectly to child maladjustment (via maternal harsh parenting; see Figure 1.). Covariances between the Time 1 predictors evidencing significant bivariate correlations and between the intercept and the slope factor were included in the model. The number of assessments at which each mother had a partner was included as a control variable of maternal harsh parenting to control for potential effects of partner's presence on parenting. (The number of time points with a partner was not controlled for in predicting partner aggression because it was not a significant predictor.) We also controlled for potential effects of all Time 1 predictors on maternal harsh parenting. Finally, covariances between the Time 1 predictors and child maladjustment were included based on the significance of bivariate correlations, which indicated maternal depression and history of abuse. The model fit the data well, χ2 = 37.70, df = 35, p = .35, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .01.

Figure 1.

Partner aggression predicts child maladjustment via maternal harsh parenting. Note. CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale; CTS2 = Conflict Tactics Scale 2. Bold lines indicate significant associations. The intercept and slope of partner aggression were free to covary as indicated by the curved line between them. The covariances between the Time 1 predictors and maternal harsh parenting, between the Time 1 predictors and child maladjustment, and between number of time points with a partner and maternal harsh parenting are not depicted here.

The intercept and slope factors of partner aggression were significantly associated with Time 4 maternal harsh parenting. Higher levels of Time 1 partner aggression and a smaller decrease in partner aggression over time independently predicted greater Time 4 maternal harsh parenting. Neither the intercept nor the slope factor of partner aggression predicted directly to Time 4 child maladjustment. However, maternal harsh parenting significantly predicted higher Time 4 child maladjustment, providing support for indirect effects of partner aggression via maternal harsh parenting. The associations between the Time 1 predictors and the growth factors of partner aggression remained the same in this model except for the significant negative association between maternal potential for violence and the slope factor, which became nonsignificant (see Table 2, Model 2). Of the Time 1 predictors, only maternal history of abuse significantly predicted greater maternal harsh parenting. The number of assessments at which each mother had a partner was significantly and negatively associated with Time 4 maternal harsh parenting, suggesting that the presence of a partner is associated with lower levels of harsh parenting. The model accounted for 28% of the variance in the intercept, p < .00, and 11% of the variance in the slope, p < .05, of partner aggression; 40% of the variance in Time 4 maternal harsh parenting, p < .00; and 5% of the variance in Time 4 child maladjustment, p = .05.

Discussion

In the present study, we accounted for contextual and psychosocial risk factors in examining the consequences of partner aggression at birth and over the first 3 years of life for harsh parenting and young child maladjustment in a high-risk sample. The significant decline in partner aggression over the 3-year period is in line with studies indicating fluctuations in partner aggression over time (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007) and a general decline in partner aggression around childbirth (Martin et al., 2001; Saltzman et al., 2003). Given the high rates of Time 1 partner aggression, the decline might reflect disengagement from conflictual relationship dynamics (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007). Time 1 partner aggression was not associated with Time 4 partner status, suggesting that the decline was not due to aggressive partners separating; however, it was not possible to assess whether switching partners accounted for some of the decline. The particularly sharp decline in partner aggression between Time 1 and Time 2 (as reflected in the decreased prevalence of aggression from 84.6% to 50.0%) might indicate changes in family dynamics due to having a child. Jasinksi (2004) reported that the birth of a first child is associated with partner physical aggression ceasing, perhaps due to feelings of responsibility to the child. That aggression levels continued to decrease, albeit more modestly, though Time 4 suggests that the potentially stressful, developmental transitions in the first 3 years of life might not be associated with subsequent increases in partner aggression.

Maternal age, indices of maternal psychosocial functioning, and early experiences predicted the initial level of partner aggression. These may be interpreted as indicators of negative experiences with early central relationships and of decreased capacity for emotion regulation, known risk factors for the formation of aggressive intimate partner relationships (Ehrensaft, 2009). Consistent with some prior research (Torres et al., 2000), maternal ethnicity was not significantly associated with partner aggression after controlling for other risk factors. However, acculturation (not included in these analyses) might be more important than ethnicity in predicting partner aggression (Torres et al., 2000).

Only maternal age and depression predicted the trajectory of partner aggression over time, with higher levels of depression and younger age being associated with greater declines in partner aggression. These results are somewhat counterintuitive. However, considering that higher levels of maternal depression and being younger predicted greater initial levels of partner aggression, these results are in line with the finding that high initial levels of aggression predict greater change over time (e.g., Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007). Lawrence and Bradbury suggested that this observed decline for couples with high initial levels of aggression might be associated with the emergence of covert conflict dynamics such as withdrawal. It is also possible that the effects of maternal depression and being younger on partner aggression over time is related to a ceiling effect given the high Time 1 levels of aggression for the sample overall, and particularly for younger mothers and those with symptoms of depression.

Our findings suggest that, beginning at birth, if not earlier (e.g., Kanoy et al., 2003), partner aggression plays an important role in shaping parenting practices. The effect of Time 1 partner aggression on Time 4 maternal harsh parenting suggests that initial levels of partner aggression create an atmosphere in which aggressive dynamics become the norm for family interactions, whether with partners or children. The association between initial level of partner aggression and subsequent harsh parenting might also result from the enduring effects on a mother's internal representations of her child and her caregiving (e.g., Huth-Bocks et al., 2004). The potential effects of prenatal partner aggression on child stress regulatory systems should also be considered in future work (Van den Bergh, Mulder, Mennes, & Glover, 2005); more dysregulated or temperamentally difficult infants could elicit harsher parenting.

Change in partner aggression through Time 4 had an independent association with maternal harsh parenting, suggesting that, regardless of the initial level, a smaller decrease in partner aggression over time led to higher Time 4 harsh parenting. A lack of change in partner aggression is potentially indicative of a static relationship with chronic, unremitting negative dynamics that lead to distress (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007), which might spill over into the parent–child relationship (Erel & Burman, 1995). The association between less decline in partner aggression and higher levels of harsh parenting suggests that the transfer of aggression into the parent–child relationship does not relieve strain on the partner relationship; rather, consistently high levels of aggression spill over from one relationship to the other, potentially due to increased levels of stress reactivity and effects on neural systems involved in emotion regulation (e.g., Sturge-Apple et al., 2009). In contrast, decreasing partner aggression might indicate flexibility in the relationship and cause partners to feel relief, leading to lower levels of harsh parenting. It is worthy to note that we controlled for multiple risk factors; thus, our findings indicate that partner aggression independently predicts harsh parenting or mediates the effects of these other variables.

As expected, maternal harsh parenting predicted higher Time 4 child maladjustment. Maternal harsh parenting in early childhood appears to predict more severe consequences for a child's subsequent development (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001). This could be due to the impact of early adversity on rapidly developing biological systems critical for development of effective emotion regulation (Gunnar et al., 2006). However, the measurement of maternal harsh parenting and child maladjustment at the same time point limits our capacity to make causal inferences. On the other hand, the lack of a direct association between partner aggression and child maladjustment is in contrast to findings in the literature (Cummings & Davies, 2010), which often involve white, middle-class samples (Cummings & Davies, 2002). However, the results from studies with high-risk ethnic minority youth and low-SES preschoolers have shown very low to moderate associations between partner aggression and child maladjustment (Ingoldsby et al., 1999). It is possible that, in the presence of multiple risk factors, partner aggression is relatively less influential for high-risk families. Alternatively, declining levels of partner aggression might be associated with the emergence of more covert destructive relationship dynamics. In future longitudinal studies, researchers should examine multiple aspects of the partner relationship. It is also important to note that partner involvement in childrearing (not assessed in the current study) appears to moderate the impact of negative relationship dynamics on young children (Crockenberg et al., 2007). Finally, the question posed in the present study was whether initial levels of partner aggression at birth and change over time have direct effects on child maladjustment, which is distinct from a direct assessment of whether partner aggression at any one time point directly affects child maladjustment.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, additional psychosocial and contextual risk factors not considered in the present study, including family size, might contribute to partner aggression and maternal harsh parenting. Second, the reciprocal effects of partner aggression and child characteristics, including gender and temperament, should be considered in a longitudinal, process-oriented model (Cummings & Davies, 2002). That a larger amount of variation in partner aggression over time (vs. initial level) remained unexplained after including the Time 1 predictors suggests that other factors, including child characteristics, likely effect partner aggression over the early years of childrearing. Third, a causal association between partner aggression over time and maternal harsh parenting could have been more cogently addressed by including controls for harsh parenting at earlier time points (e.g., Sturge-Apple et al., 2009). Fourth, relying on maternal self-reports could have led to underreporting. However, considering the difficulties associated with observing aggressive partner and parent–child dynamics, self-report measures are commonly used. In addition, due to the challenges of obtaining observational and multiple-respondent data in a large, high-risk, multilingual sample, we propose that the use of maternal report, with acknowledged limitations, represents a useful first step in increasing understanding of the unique challenges faced by a diverse, high-risk sample. Moreover, demographic variables such as age and ethnicity, which are unlikely to be affected by self-report, demonstrated significant and coherent associations with the more subjective self-report measures. Finally, the use of maternal self-report across several measures might have led to inflated associations due to shared method variance. However, the small to moderate bivariate correlations found in the present study suggest that this was not a driving force behind the reported findings.

Despite these limitations, our results extend previous research findings by using a longitudinal design to examine partner aggression in high-risk families during the first 3 years of life and its role in influencing harsh parenting and young child maladjustment while taking in to account contextual and psychosocial risk factors. Although the partner relationship has been conceptualized as a guiding force in family dynamics (Rossman, 1986), it is not a frequent target of prevention and intervention efforts in high-risk families. The observed decrease in partner aggression, most dramatically from birth to age 1 year, should be noted as a potential opportunity for intervention. As levels of aggression decline, partners might be especially likely to benefit from learning skills for new, adaptive methods of problem solving in the relationship. Young age and symptoms of depression appear to indicate a greater likelihood of change in partner aggression over this period and might be notable factors in deciding who would benefit from such interventions. Finally, as initial levels of partner aggression at birth and subsequent changes over the first 3 years of life were both found to predict child maladjustment (via maternal harsh parenting), the assessment of and services targeting partner aggression should begin prenatally and continue throughout infancy and toddlerhood.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the following grants: MH059780 and MH046690, NIMH, U.S. PHS; DA017592, DA021424, and DA023920, NIDA, U.S. PHS; and HD045894, NICHD, U.S. PHS. The authors thank the staff and participants that made this study possible and Matthew Rabel for editorial assistance.

Contributor Information

Alice M. Graham, Oregon Social Learning Center and University of Oregon

Hyoun K. Kim, Oregon Social Learning Center

Philip A. Fisher, Oregon Social Learning Center and University of Oregon

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Child Behavior Checklist/ 2-3 and 1992 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M. Patterns of marital change across the transition to parenthood: Pregnancy to three years postpartum. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52:5–19. doi: 10.2307/352833. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Brady-Smith C, Brooks-Gunn J. Links between childbearing age and observed maternal behaviors with 14-month-olds in the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:104–129. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10007. [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda JR, Brown SL. Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research. 2007;36:945–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:61–73. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.1.61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Burchinal M, Payne CC. Marital perceptions and interactions across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:611–625. doi: 10.2307/353564. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, Lekka SK. Pathways from marital aggression to infant emotion regulation: The development of withdrawal in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.009. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK. Family and relationship predictors of psychological aggression and physical aggression. In: O'Leary KD, Woodin E, editors. Psychological and physical aggression in couples: Causes and interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 99–118. doi: 10.1037/11880-005. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM, Kouros C, Elmore-Staton L, Buckhalt JA. Marital psychological and physical aggression and children's mental and physical health: direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:138–148. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch CA, Mangelsdorf SC, McHale JL. Marital behavior and the security of preschooler–parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:144–161. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.144. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann T, Striano T, Friederici AD. Infants’ electric brain responses to emotional prosody. NeuroReport. 2005;16:1825–1828. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000185964.34336.b1. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000185964.34336.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. doi: 10.1037/00332909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Fisher PA, Early Experience, Stress, and Prevention Network Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive intervention research on neglected and maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:651–677. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawaii Family Stress Center . Early identification training materials: Healthy Families America. Author; Honolulu, HI: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huth-Bocks AC, Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, von Eye A. The impact of maternal characteristics and contextual variables on infant-mother attachment. Child Development. 2004;75:480–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00688.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Owens EB, Winslow EB. A longitudinal study of interparental conflict, emotional and behavioral reactivity, and preschoolers’ adjustment problems among low-income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:343–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1021971700656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski JL. Pregnancy and domestic violence: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2004;5:47–64. doi: 10.1177/1524838003259322. doi: 10.1177/1524838003259322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Norwood WD, McDonald R. Physical violence and other forms of marital aggression: Links with children's behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:223–234. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.223. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoy K, Ulku-Steiner B, Cox M, Burchinal M. Marital relationship and individual psychological characteristics that predict physical punishment of children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.17.1.20. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.17.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe R, Kempe CH. Assessing family pathology. In: Helfer RE, Kempe CH, editors. Child abuse and neglect. Ballinger; Cambridge, MA: 1976. pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM, Feingold A. Men's aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Pears KC, Fisher PA, Connelly CD, Landsverk JA. Trajectories of maternal harsh parenting in the first 3 years of life. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.002. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher J. The Kempe Family Stress Inventory: A review. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00115-5. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations. 2000;49:25–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Trajectories of change in physical aggression and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:236–247. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.236. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Huth-Bocks AC, Semel MA, Shapiro DL. Trauma symptoms in preschool-age children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:150–164. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017002003. [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Martin SL, Kupper LL, Casanueva C, Guo S. Partner violence among women before, during, and after pregnancy: Multiple opportunities for intervention. Women's Health Issues. 2007;17:290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Mackie L, Kupper LL, Buescher PA, Moracco KE. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285:1581–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 5th ed. Authors; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Malone J, Tyree A. Physical aggression in early marriage: Prerelationship and relationship effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:594–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.594. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.62.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman BL. Developmental perspectives in family therapy with children. In: Fishman HC, Rossman BL, editors. Evolving models for family change: A volume in honor of Salvador Minuchin. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Goodwin MM. Physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: An examination of prevalence and risk factors in 16 states. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2003;7:31–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1022589501039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, O'Leary SG. Parent and partner violence in families with young children: Rates, patterns, and connections. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:435–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M. Using latent growth curve models to study developmental processes. In: Gottman JM, editor. The analysis of change. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. doi: 10.2307/351733. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1891/088667004780927800. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM. The role of mothers’ and fathers’ adrenocortical reactivity in spillover between interparental conflict and parenting practices. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:215–225. doi: 10.1037/a0014198. doi: 10.1037/a0014198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S, Campbell J, Campbell DW, Ryan J, King C, Price P, Laude M. Abuse during and before pregnancy: Prevalence and cultural correlates. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:303–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BRH, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1996;154:785–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]