Abstract

Background

Remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) is a novel method of protecting the liver from ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) injury. Protective effects in the early phase (4–6 h) have been demonstrated, but no studies have focused on the late phase (24 h) of hepatic I–R. This study analysed events in the late phase of I–R following RIPC and focused on the microcirculation, inflammatory cascade and the role of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 (CINC-1).

Methods

A standard animal model was used. Remote preconditioning prior to I–R was induced by intermittent limb ischaemia. Ischaemia was induced in the left and median lobes of the liver (70%). The animals were recovered after 45 min of liver ischaemia. At 24 h, the animals were re-evaluated under anaesthesia. Hepatic microcirculation, sinusoidal leukocyte adherence and hepatocellular death were assessed by intravital microscopy, hepatocellular injury by standard biochemistry and serum CINC-1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results

At 24 h post I–R, RIPC was found to have improved sinusoidal flow by increasing the sinusoidal diameter. There was no effect of preconditioning on the velocity of red blood cells, by contrast with the early phase of hepatic I–R. Remote ischaemic preconditioning significantly reduced hepatocellular injury, neutrophil-induced endothelial injury and serum CINC-1 levels.

Conclusions

Remote ischaemic preconditioning is amenable to translation into clinical practice and may improve outcomes in liver resection surgery and transplantation.

Keywords: ischaemia reperfusion, transplant

Introduction

Ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) injury is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in liver transplant surgery. Poor initial graft function (PIF) occurs in 15–25% of patients and primary non-function (PNF) in about 5%.1 Ischaemia–reperfusion results in reduced perfusion of the liver and the induction of an inflammatory cascade involving the adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells and trans-migration in the sinusoids. The perfusion abnormality correlates with the severity and duration of ischaemia.2 Hepatic reperfusion injury has an early and a late phase.3 In the early phase, the key cells responsible for the activation of the inflammatory cascade, the release of free radicals and cytokines, and endothelial injury are Kupffer cells; in the late phase of hepatic I–R, neutrophils release free radicals and cause endothelial and parenchymal injury.

Ischaemic preconditioning (IPC) is an adaptive response in which tolerance to prolonged ischaemia is induced in a target organ by prior brief periods of ischaemia.

Ischaemic preconditioning has been shown to significantly reduce warm hepatic I–R in both experimental and preliminary clinical studies.4–7 Preconditioned animals have reduced sinusoidal leukocyte adherence,8 and improved energy status and mitochondrial function,9 all of which result in a survival advantage following I–R injury.10 Hypothermic preconditioning has also been shown to reduce warm liver I–R in experimental models.11 Remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) involves the protection of an organ from prolonged ischaemia by brief periods of ischaemia and reperfusion to a remote organ. Our previous studies12,13 have shown that RIPC improved parenchymal perfusion and oxygenation and reduced hepatocellular injury in the early phase of I–R injury. Previous studies on hepatic I–R7 have shown the late phase of hepatic I–R to be associated with significantly increased I–R injury in lean and obese rat models and decreased survival in obese rat models. Vollmar et al. used intravital microscopy to show significantly increased endothelial neutrophil adhesion and decreased sinusoidal perfusion in the hepatic microcirculation.2

The studies discussed previously suggest that in the clinical setting hepatic I–R injury in the late phase may have a major bearing on patient survival, graft function and morbidity. None of the RIPC studies on liver have focused on the modulation of the late phase of hepatic I–R injury, although this may be of greater importance to overall outcome.

Neutrophils are the key cells in the late phase of hepatic I–R. Cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC) is an important cytokine responsible for the activation of neutrophils in hepatic I–R. CINC is a peptide in the interleukin-8 (IL-8) superfamily and has been functionally described as a potent neutrophil chemoattractant in rats.14 Kupffer cells, which comprise the largest fixed macrophage population in the liver, produce cytokines when activated and represent an important source of CINC.

The role of CINC in hepatic I–R

Induced by IL-1, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and bacterial products, CINC-1 promotes both neutrophil rolling and adhesion, probably through the upregulation of surface integrins, and directs neutrophils to sites of bacterially induced inflammation. CINC-1 stimulates neutrophil activity by promoting cathepsin G release from azurophilic granules, resulting in bactericidal effects. Hisama et al. demonstrated that liver mRNA transcripts of CINC peaked at 3 h and serum CINC levels peaked at 6 h after reperfusion and then gradually decreased.15 In animal models, treatment with heparin or gadolinium chloride inhibited serum CINC levels and CINC transcript expression in liver and, following CINC inhibition, neutrophilic infiltration of the liver 24 h after reperfusion was significantly decreased. Pharmacological preconditioning by glycine16 and heat shock preconditioning17 have been shown to reduce serum CINC-1 levels in hepatic reperfusion injury. No studies have investigated the effect of RIPC on CINC-1 in hepatic reperfusion injury.

Our hypothesis

We investigated the effects of RIPC in the late phase of hepatic I–R in real time using intravital microscopy to study in vivo microcirculatory changes. Based on observations in the early phase of hepatic I–R, we hypothesized that RIPC would abolish the effects of late hepatic I–R on microcirculatory flow by modulating endothelial neutrophil adhesion, sinusoidal perfusion and hepatocellular death. We also hypothesized that RIPC would reduce neutrophil adhesion by modulating CINC production.

Materials and methods

Animals and surgical procedures

All experiments were conducted under project license from the UK Home Office in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Male Sprague–Dawley rats, weighing 250–300 g, were used. Animals were kept in a temperature-controlled environment under a 12 : 12 h light : dark cycle and were allowed access to tap water and standard rat chew pellets ad libitum. Animals were anaesthetized with 4 l/min of isoflurane and maintained under 1.0–1.5 l/min of oxygen and 0.5–1.0% isoflurane. They were allowed to breathe spontaneously through a concentric mask connected to an oxygen regulator and monitored with a pulse oximeter (Biox 3740; Ohmeda, Inc., Louisville, CO, USA).

Animal model

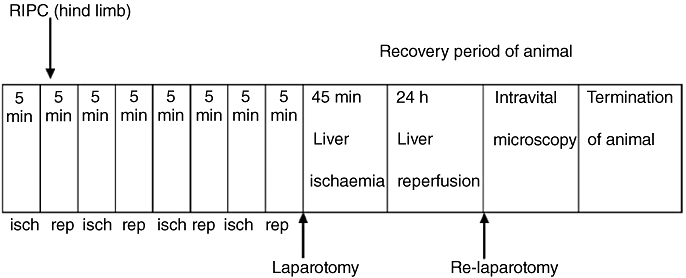

The experiment design is outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Design of recovery experiments. RIPC, remote ischaemic preconditioning; isch, ischaemia; rep, reperfusion

Hepatic I–R

Laparotomy was carried out through a midline incision. The ligamentous attachments of the liver were cut and the liver exposed. A standard model of lobar hepatic ischaemia of the left lateral and median lobes (70% of the liver)18 was used. Ischaemia was induced by clamping the corresponding vascular pedicle with an atraumatic microvascular clamp. This model avoided splanchnic congestion. Hepatic ischaemia was maintained for 45 min followed by 24 h of reperfusion. All animals received an i.v. bolus of heparin (20 U/kg) prior to clamping to prevent potential thrombus formation in the hepatic artery.

Limb preconditioning

The technique used for RIPC involved the application of a tourniquet around the thigh of one of the hind limbs. Limb perfusion was monitored by a laser Doppler (Moor Instruments, Surrey, UK) and the tourniquet around the limb was tightened until no flow was detected. The procedure involved 5 min of ischaemia followed by 5 min of reperfusion. This was repeated four times.19,20

Recovery after initial surgery and monitoring

Recovery was closely monitored. Animal behaviour was assessed every hour for 4 h and then at 22 h and 24 h. Signs of poor clinical condition were lethargy, ruffled fur, abdominal guarding upon palpation, lack of grooming and decreased food intake. Animals which appeared to do poorly were killed before the 24 h reperfusion endpoint.

After 24 h of reperfusion, the animals were re-anaesthetized. Polyethylene catheters with an inner diameter of 0.76 mm (Sims Portex Ltd, Hythe, UK) were inserted into the right carotid artery to collect blood and for exsanguination and termination of the animal at the end of the experiment. Similar polyethylene catheters with an inner diameter of 0.40 mm (Sims Portex Ltd) were inserted into the left jugular vein for the purposes of administering normal saline (1 ml/100 g body weight per hour) to compensate for intraoperative fluid loss. Animals were placed in a supine position on heating mats (Harvard Apparatus Ltd, Edenbridge, UK) to maintain their temperature. The abdominal sutures were carefully opened and the liver examined by intravital microscopy.

Experimental groups

Two groups of animals were studied (n = 6 in each group). In Group 1 (the I–R group), animals were subjected to liver ischaemia for 45 min and reperfusion for 24 h. Ischaemia was induced using a microvascular clamp. In Group 2 (the RIPC + I–R group), animals were preconditioned as outlined above immediately prior to the induction of ischaemia. Both groups were terminated after intravital microscopy at 24 h.

Intravital videofluorescence microscopy

During the second laparotomy, performed at 24 h to facilitate intravital microscopy, the animals were maintained under anaesthesia using isoflurane and oxygen. Their temperature was maintained using warm mats regulated by thermostat.

The left and median lobes of the liver (70% ischaemia) were exposed and placed upon a glass mount and covered with a cover slip. The liver was continuously irrigated with normal saline. A drop of saline was placed on the cover slip and the tip of the lens of the microscope was immersed in the saline drop.

Texas Red, FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) and DAPI dyes were used. A Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) microscope (Nikon epi-illumination system with filter block set suitable for Texas Red, FITC and DAPI dyes) coupled to a CCD camera [JVC TKC1360 (Osaka, Japan) colour video camera] was used. Magnification was set at ×10 and ×40. The microscopy images were transferred by the camera to the video monitor and recorded for offline analysis. Quantitative assessment of microcirculatory parameters was performed offline by frame-by-frame analysis of the recorded images. Microcirculation was assessed by evaluating acinar perfusion in 10 randomly chosen acini, and leukocyte–endothelial interaction in 10 post-sinusoidal venules. Microcirculatory parameters were calculated according to previous studies by Vollmar et al. and Brock et al.21–23

Red blood cell velocity

A 0.5-ml quantity of FITC labelled red blood cells (RBC) prepared from rat blood suspended in glucose saline buffer solution (20 mg FITC/ml of RBC) were administered i.v. to assess the velocity of RBC flow.24 Ten randomly chosen non-overlapping rappaport acini were assessed at each time-point and the mean value was calculated. Red blood cell velocity was calculated by assessing the extent of RBC movement [in microns (µm)] in each sinusoid in subsequent frames (L). A total of 25 frames were captured per second. Hence, velocity was calculated using the formula: L × 25/number of frames moved.20–22

Sinusoidal perfusion and perfusion index

The sinusoidal perfusion index (PI) was evaluated as the ratio of perfused hepatic sinusoids [continuously perfused sinusoids (Scp) + intermittently perfused sinusoids (Sip)] to total visible sinusoids [including non-perfused sinusoids (Snp)].23

Therefore, PI = (Scp + Sip)/(Scp + Sip + Snp).

Sinusoidal diameter

Sinusoidal diameter (D) was defined as the mean of the length across 10 randomly chosen hepatic sinusoids at each time-point and expressed in microns (µm).

Sinusoidal blood flow

Sinusoidal blood flow was calculated from the data on RBC velocity and the measure of the sinusoidal diameter using the formula: (V) × 22/7 × (D/2)2.

Neutrophil adhesion

Rhodamine 6G (0.3 mg/kg)25 was given i.v. to stain neutrophils. Rhodamine has an affinity for binding to neutrophils and its use in visualizing adherent neutrophils is well established. The numbers of leukocytes adherent to the sinusoidal endothelium and venular endothelium were counted as those stationary for a period of 30 s under green filter light and expressed as leukocytes/mm2. The area of the vessels was calculated using diameter (D) and length (L) and assuming cylindrical geometry as: 3.14 × D × L.

Hepatocellular cell death

Hepatocyte cell death was assessed by i.v. injection of propidium iodide (0.05 mg/kg).21,24 Numbers of nuclei stained with the dye were counted under the camera and expressed as the number of dead cells/high-power field seen on the video monitor.

Histology

At the end of the experiment, liver tissue was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin in preparation for light microscopy analysis. Sections were cut at 5 µm and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological analysis. Histological changes in the H&E-stained sections were graded by a pathologist blinded to the study protocol. Grading was based on the extent of necrosis as follows: necrosis of 0–25% scored 1; necrosis of 25–50% scored 2; necrosis of 50–75% scored 3, and necrosis of >75% scored 4. Neutrophils were observed by light microscopy in both groups and neutrophil adhesion by microscopy was subjectively assessed by the pathologist.

CINC assay

CINC is a cytokine secreted by activated Kupffer cells following I–R injury, which acts as a potent neutrophil chemoattractant. CINC levels were measured to assess the effect of RIPC on the modulation of neutrophil activation.

A quantity of 50 µl of assay diluent was added to each well. Then, 50 µl of standard, control or sample was added to each well. The plate was gently tapped for 1 min to mix the contents, covered with an adhesive strip and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Each well was aspirated and washed five times with wash buffer (400 µl). Subsequently, 100 µl of rat CINC-1 conjugate was added to each well. The plate was covered with adhesive strip and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The wells were aspirated and washed five times, after which 100 µl of substrate solution was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min under protection from light. Then, 100 µl of stop solution was added to each well. The plate was gently tapped to ensure mixing. Optical density was measured within 30 min using a microplate reader set to 450 nm (with the correction wavelength set at 540 nm or 570 nm).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences were considered significant when P-values were <0.05. Comparisons between groups were performed using unpaired t-tests.

Results

Survival

One of the six animals in the I–R group died before the end of the recovery period as a result of severe reperfusion injury (as indicated in postmortem histological analysis) and was therefore excluded from intravital analysis. All animals in the RIPC + I–R group survived to 24 h of reperfusion.

Microcirculation

Changes in liver microcirculation at 24 h after I–R were evaluated by intravital microscopy and compared with those in animals that had undergone preconditioning.

Effects of hepatic I–R on microcirculatory parameters at 24 h

The mean velocity in the I–R group at 24 h was 399.86 ± 48.09 µm/s (Fig. 2). The mean sinusoidal flow in the I–R group at 24 h was 21.88 ± 2.58 µm/s (Fig. 3). The mean sinusoidal diameter in the I–R group at 24 h was 8.37 ± 0.22 µm (Fig. 4). A significantly lower mean PI of 0.656 ± 0.15 was observed in the I–R group at 24 h (Fig. 5).

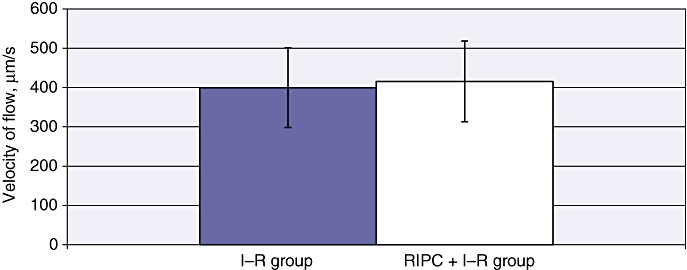

Figure 2.

Velocity of red blood cell flow in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. P-value = not significant

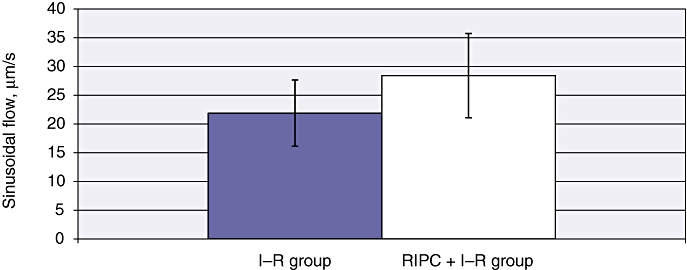

Figure 3.

Sinusoidal flow in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h, calculated as V × (D/2)2 ×π, where V is the velocity of red blood cells and D is sinusoidal diameter. Better flow was found in preconditioned animals. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. P-value = not significant

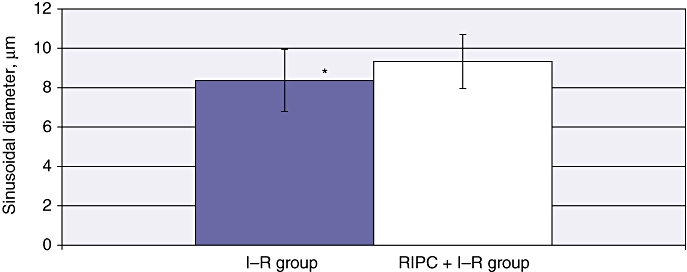

Figure 4.

Sinusoidal diameter in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. A significantly increased diameter was found in the preconditioned group. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.001 (I–R/RIPC + I–R)

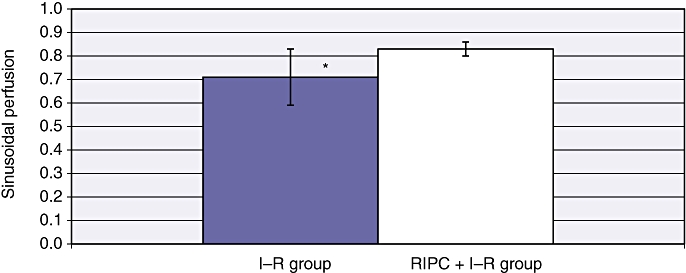

Figure 5.

Sinusoidal perfusion in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. The perfusion index in preconditioned animals was significantly higher than in non-preconditioned animals. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.007 (I–R/RIPC + I–R)

Effects of RIPC on outcomes of hepatic I–R at 24 h

Mean velocity in the RIPC + I–R group was higher than in the I–R group at 24 h (415.75 ± 48.12 µm/s) (Fig. 2). Both sinusoidal flow (28.43 ± 2.99 µm/s) (Fig. 3) and sinusoidal diameter (9.33 ± 0.17 µm) (Fig. 4) were significantly higher in the RIPC + I–R group than the I–R group at 24 h. The sinusoidal PI in the RIPC + I–R group was 0.83 ± 0.15 at 24 h (Fig. 5).

These data suggest that preconditioning improved sinusoidal flow in hepatic I–R, but did not influence the velocity of flow. The increase in sinusoidal flow was a direct result of the increase in sinusoidal diameter according to the formula described for calculating sinusoidal flow. Preconditioning also increased sinusoidal perfusion in hepatic I–R.

Neutrophil adhesion and cell death in hepatic I–R at 24 h

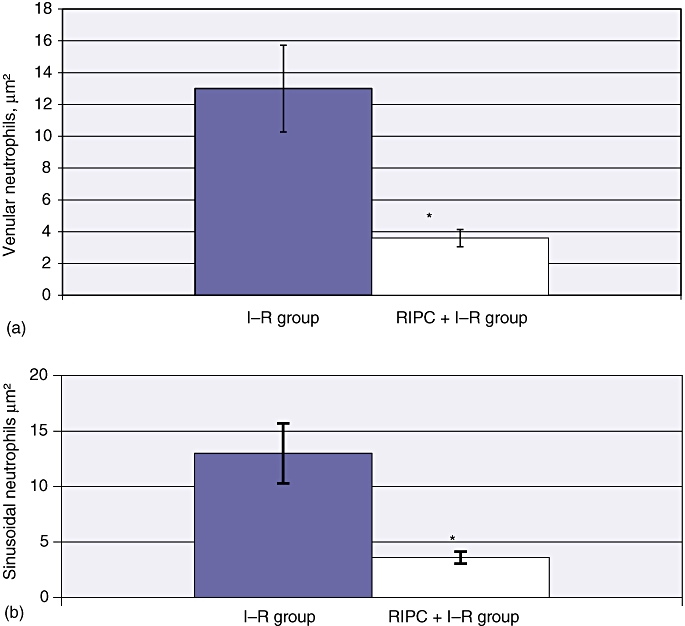

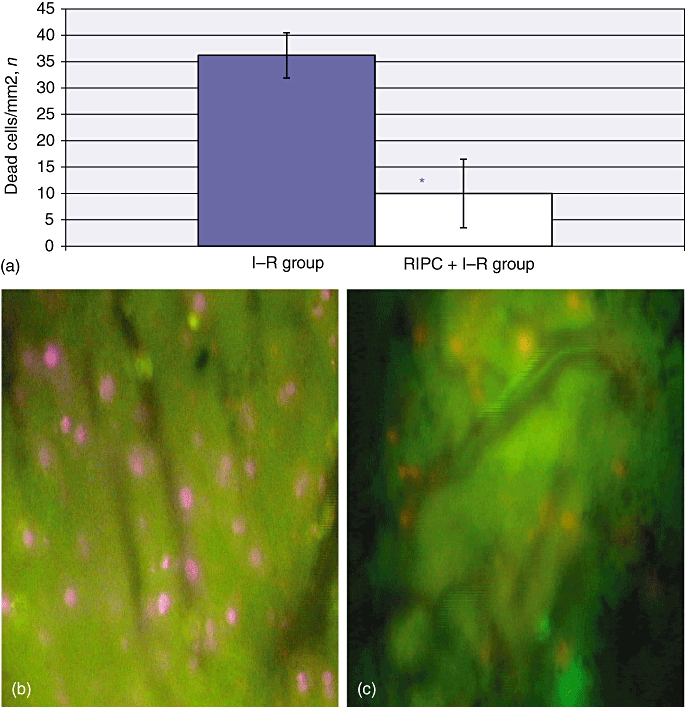

Venular neutrophil adhesion and sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion were 1363 ± 59 cells/µm2 and 187.33 ± 9.47 cells/µm2, respectively, in the I–R group at 24 h (Fig. 6). Hepatocellular cell death in the I–R group at 24 h was 36 ± 2.9 cells/mm2 (Fig. 7a–c).

Figure 6.

(a) Venular neutrophil adhesion in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. Venular neutrophil adhesion was significantly reduced in preconditioned animals compared with non-preconditioned animals. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.00 (I–R/RIPC + I–R). (b) Sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion in I–R and RIPC + I–R at 24 h. Sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion was significantly reduced in the preconditioned group compared with the non-preconditioned group. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.00 (I–R/RIPC + I–R)

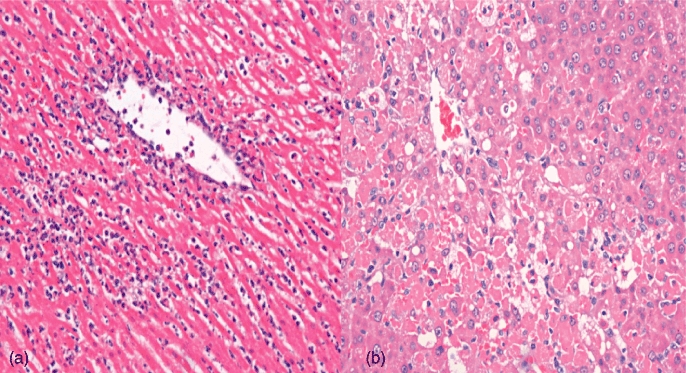

Figure 7.

(a) Hepatocellular cell death in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h by propidium iodide staining. The number of cells divided by the surface area of the field gives the number of cells/mm2. Dead cells are stained pink. Hepatocellular cell death in the I–R group (b) was significantly higher than in the RIPC + I–R group (c). Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. *P = 0.00 (I–R/RIPC + I–R). (Original magnification × 40)

Effects of RIPC on neutrophil adhesion and cell death in hepatic I–R at 24 h

The RIPC + I–R group showed significant decreases in venular and sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion, with mean values of 367.61 ± 20.35 cells/µm2 and 52.45 ± 9.47 cells/µm2, respectively (Fig. 6). Hepatocellular cell death in preconditioned animals was 10 ± 1.92 cells/mm2 (Fig. 7a–c). These results suggest that preconditioning significantly reduced neutrophil adhesion in both sinusoids and venules, and also decreased hepatocellular death.

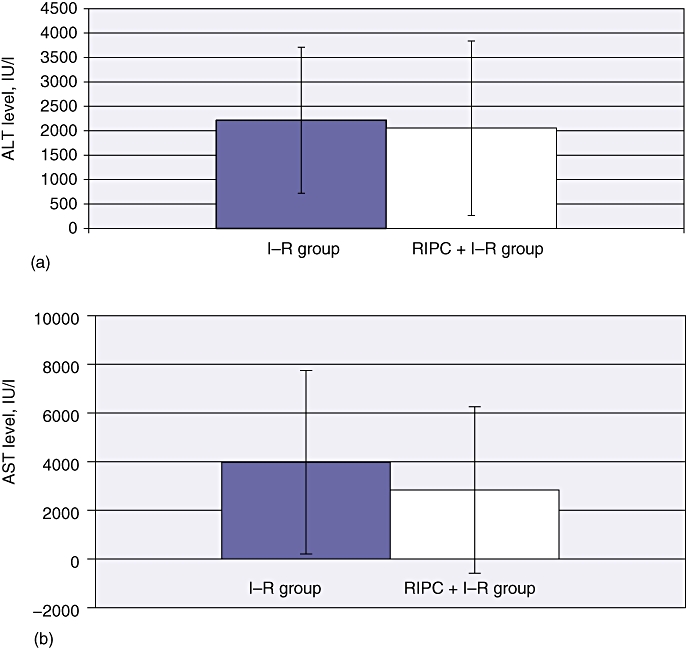

Hepatocellular injury in hepatic I–R at 24 h

The hepatic transaminase level in the I–R group at 24 h was 4000 IU/ml (P < 0.01). The patterns of aspartate transaminase (AST) levels and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were similar (Fig. 8). Remote ischaemic preconditioning significantly reduced transaminase levels to 2900 IU/ml, which suggested a reduction in hepatocellular injury.

Figure 8.

Transaminase levels in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and in remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. Transaminase levels were significantly reduced in preconditioned animals. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. (a) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (P = 0.881). (b) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (P = 0.630)

Histological changes in I–R and effects of RIPC at 24 h

Histology showed very severe damage with abundant ballooning degeneration and necrosis was seen in the I–R injury group. Very diffuse and significant neutrophil adhesion was seen in the I–R group. Apoptosis was evident in the I–R group. The RIPC group showed less necrosis with some ballooning and degeneration, as well as neutrophilic infiltration (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Histology in (a) ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and (b) remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h. Very severe injury with abundant ballooning degeneration, necrosis and very diffuse and significant neutrophil adhesion is seen in the I–R group. Apoptosis is evident. The RIPC + I–R group shows less injury, with some ballooning and degeneration, as well as neutrophilic infiltration. (Haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification × 20)

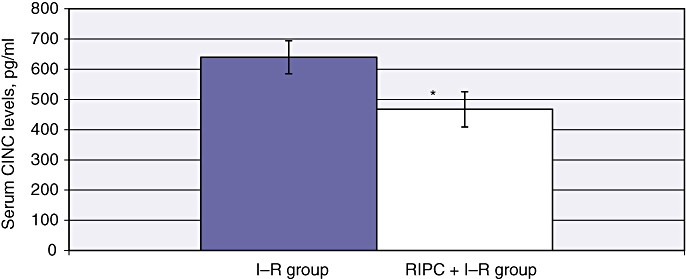

CINC levels in hepatic I–R at 24 h

Serum cytokine levels in the I–R group at 24 h were 15 306 ± 1222.04 pg/ml, whereas RIPC reduced CINC levels to 467.76 ± 26.06 pg/ml (P < 0.01) (Fig. 10). These data suggest reduced CINC levels and neutrophil activation in preconditioned animals.

Figure 10.

Serum CINC levels in ischaemia–reperfusion (I–R) and remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) + I–R at 24 h were significantly higher in the I–R group than in the RIPC + I–R group. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. (*P = 0.043)

Discussion

Animal model

Hepatic I–R (recovery), stability, death and complications

In this study, we established a recovery model of warm hepatic I–R to study the effects of I–R. This model of partial (70%) hepatic ischaemia involved 45 min of ischaemia to the left and median lobes of the liver, followed by 24 h of reperfusion. This model was considered suitable for studying the effects of RIPC based on the use of partial hepatic I–R models for investigating hepatic microcirculatory changes in I–R.26

Using intravital microscopy, these hepatic I–R models have demonstrated significant post-ischaemic changes resulting in hepatic microvascular failure induced by 45 min of ischaemia followed by reperfusion; this suggests that the model used in this study is a model of severe I–R.

A partial hepatic I–R model was used rather than a transplant model because the study was limited to investigating the effects of warm hepatic I–R over 24 h and the impact of RIPC on microcirculatory disturbances caused by warm I–R over 24 h. As this was a model of partial I–R, portal flow was not totally occluded and thus portal hypertension was avoided in the study model.

Previous recovery studies have used partial hepatic I–R models to investigate the effects of warm hepatic I–R and the impact of IPC8,10 and hypothermic preconditioning.11 Terajima et al. used intravital microscopy to demonstrate the beneficial effect of hyperthermic preconditioning on post-ischaemic hepatic I–R.27 No previous studies have demonstrated the effects of RIPC on hepatic I–R after 24 h of reperfusion.

RIPC model

This is the first in vivo study to demonstrate the effects of RIPC in hepatic I–R in the late phase of hepatic I–R. This model of four cycles of RIPC was produced by applying a tourniquet to the hind limb for four 5-min cycles of remote ischaemia, immediately followed by hepatic ischaemia for 45 min and reperfusion for 24 h. This model demonstrated significant protective effects of RIPC in the early phase of hepatic I–R, in line with our previous study,3 and has also been used in the modulation of cardiac I–R injury following transplantation.19 Three or more cycles of preconditioning have been shown to be more effective than a single cycle in previous experimental studies.28–29 This finding represents the basis for our use of four cycles of RIPC in the current study. This model differs from the delayed preconditioning model described in the literature, which involves ischaemic preconditioning followed by a delayed ischaemic insult and reperfusion injury (onset after 24 h) to the liver. In our model, the onset of hepatic I–R is soon after preconditioning and the livers were removed after 24 h of reperfusion to assess the effects of RIPC on the late phase of hepatic I–R.

Intravital microscopy showed significantly increased sinusoidal and venular neutrophil adhesion and hepatocellular cell death in the late phase of I–R. The sinusoidal perfusion and sinusoidal diameter were significantly decreased in I–R at 24 h. Although there was no significant difference in velocity of flow between the I–R and RIPC + I–R groups at 24 h, sinusoidal flow was significantly lower in the I–R group as a result of the smaller sinusoidal diameter in this group. Our findings demonstrate that I–R injury caused microcirculatory failure attributable to venular and sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion in the late phase of hepatic I–R that led to endothelial injury and swelling and significant impairment of sinusoidal perfusion. Previous studies by Terajima et al.27 and Vollmar et al.2 and Goto et al.20 used intravital microscopy to show that post-ischaemic changes consistent with microcirculatory failure include impaired sinusoidal perfusion, sinusoidal constriction, and venular neutrophil adhesion leading to endothelial injury. These findings support those of our study.

Microcirculatory changes and hepatic transaminase levels, histology and CINC expression

Intravital microscopy showed significantly increased hepatocellular death in the I–R group at 24 h. Hepatic transaminases were higher in the I–R than the RIPC + I–R group, suggesting increased hepatocellular injury. Histology clearly demonstrated increased parenchymal necrosis, cell death and neutrophilic infiltration in the I–R injury group at 24 h compared with the RIPC + I–R group, which correlates with our intravital findings.

Serum CINC levels at 24 h were significantly higher in the I–R group. This suggests that increased cytokine levels were responsible for increased neutrophil activation; this correlates to our intravital findings and histological findings of increased neutrophil adhesion and infiltration, respectively. These findings also correlate to decreased sinusoidal perfusion secondary to neutrophil-induced endothelial injury and the increased hepatocellular injury and hepatocellular death observed on both histology and intravital microscopy.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning significantly reduced venular and sinusoidal neutrophil adhesion, and hepatocellular death, but caused a significant increase in sinusoidal perfusion and sinusoidal flow as a result of increased sinusoidal diameter, with no significant difference in RBC flow velocity compared with I–R at 24 h. These data suggest that the modulation of endothelial injury by reduced neutrophil adhesion and hepatocellular death and the increased flow facilitated by increased sinusoidal diameter are the key microcirculatory changes induced by RIPC to prevent hepatic microcirculatory failure and reduce hepatocellular injury in the late phase of hepatic I–R. Serum transaminases were significantly reduced in the preconditioned group, which suggests decreased hepatocellular injury, and histology showed decreased parenchymal necrosis with neutrophilic infiltration, which corroborates the intravital findings. In addition, RIPC significantly reduced serum CINC levels, which may explain the decreases in neutrophil adhesion and hepatocellular death in the preconditioned group.

The modulation of hepatic microcirculation and hepatocellular death in the late phase of hepatic I–R by RIPC suggests that RIPC protects against2 oxidative stress through the release of blood-borne biochemical messengers that induce antioxidant protective mechanisms in the liver.

Only one study on hyperthermic preconditioning has demonstrated by intravital microscopy a significant attenuation of the decrease in sinusoidal diameter, improved sinusoidal perfusion and attenuated neutrophil adhesion, as well as decreased hepatocellular cell death, which led to reduced hepatocellular injury.27 Both hypothermia and direct IPC have been shown to significantly reduce I–R injury in a warm I–R recovery rat model.8,11 There have been no studies of the effects of RIPC in the late phase of hepatic I–R.

Novel findings and comparison with the early phase of hepatic I–R

The principal manifestations of microcirculatory failure in the early phase, as shown in our previous experiments,11 are sinusoidal and venular neutrophil adhesion with decreased sinusoidal perfusion. In the late phase of hepatic I–R, sinusoidal constriction occurs and sinusoidal and venular neutrophil adhesion are significantly greater. Remote ischaemic preconditioning confers protection in the early phase of hepatic I–R12 by primarily increasing RBC velocity and sinusoidal flow secondary to increased velocity. It has no effect on sinusoidal diameter.

In the late phase, RIPC confers protection by increasing sinusoidal flow as a result of the increase in sinusoidal diameter. It has no effect on RBC velocity in I–R at 24 h.

Remote ischaemic preconditioning reduces sinusoidal and venular neutrophil adhesion in both the early and late phases of hepatic I–R and improves sinusoidal perfusion in both phases.

The absence of any difference in velocity of flow at 24 h of reperfusion may be explained by findings in the early-phase experiments, which demonstrated that, at 180 min of reperfusion, RBC velocity in the I–R group had recovered to near baseline, thus suggesting that RBC velocity would recover over time in the non-preconditioned I–R group.

In addition, serum levels of the neutrophil chemoattractant protein CINC-1 decreased significantly in the RIPC + I–R group compared with the I–R group at 24 h. The protective effects of RIPC in the late phase of hepatic I–R are not a consequence of effects in the early phase because RIPC modulates RBC velocity in the early phase, whereas an increase in sinusoidal diameter contributes to increased flow in the late phase.

Potential mechanisms in the modulation of late-phase hepatic I–R

This study demonstrated that RIPC reduced serum CINC levels in I–R at 24 h, which correlates with findings of decreased neutrophilic activation and adhesion, decreased hepatocellular injury and death. The data in this study suggest that the reduction in inflammatory cytokines has a direct and major influence on the degree of neutrophil adhesion following hepatic I–R injury.

Sinusoidal dilatation in the preconditioned group suggests that RIPC may induce endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) or haemoxygenase (HO) to induce endothelial dilatation and to protect endothelial function against oxidative stress. Both eNOS and HO are known to cause hepatic sinusoidal dilatation and to modulate endothelial function.6 Haemoxygenase also scavenges free radicals, thus exerting an antioxidant effect. The roles of these molecules in RIPC should be clarified in future experimental models.

Conclusions

This is the first in vivo study to demonstrate the beneficial effects of RIPC on hepatic microcirculation in real time in an experimental recovery model. The study demonstrates that RIPC modulates hepatic microcirculation and exerts a protective effect against reperfusion injury. The study demonstrates the modulation of cytokine release, neutrophil activation and endothelial injury as the key factor in preserving hepatic microcirculatory flow. Future studies should focus on the roles of vasoactive molecules such as eNOS and HO in order to clarify their roles in the protective strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the late Dr Neelanjana Dutt, consultant histopathologist at Kings College Hospital, London, for her invaluable contribution to pathology reporting.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, Hertl M. Selecting the donor liver: risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vollmar B, Glasz J, Leiderer R, Post S, Menger MD. Hepatic microcirculatory perfusion failure is a determinant of liver dysfunction in warm ischaemia reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1421–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Smith CW. Neutrophils contribute to ischaemia/reperfusion injury in rat liver in vivo. FASEB J. 1990;4:3355–3359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jassem W, Fuggle SV, Cerundolo L, Heaton ND, Rela M. Ischaemic preconditioning of cadaver donor livers protects allografts following transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:169–174. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188640.05459.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peralta C, Fernandez L, Panes J, Prats N, Sans M, Pique JM, et al. Preconditioning protects against systemic disorders associated with hepatic ischaemia–reperfusion through blockade of tumour necrosis factor-induced P-selectin upregulation in the rat. Hepatology. 2001;33:100–113. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peralta C, Prats N, Xaus C, Gelpi E, Rosello-Catafau J. Protective effect of liver ischaemic preconditioning on liver and lung injury induced by hepatic ischaemia–reperfusion in the rat. Hepatology. 1999;30:1481–1489. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peralta C, Closa D, Hotter G, Gelpi E, Prats N, Rosello-Catafau J. Liver ischaemic preconditioning is mediated by the inhibitory action of nitric oxide on endothelin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:264–270. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compagnon P, Lindell S, Ametani MS, Gilligan B, Wang HB, D'Alessandro AM, et al. Ischaemic preconditioning and liver tolerance to warm or cold ischaemia: experimental studies in large animals. Transplantation. 2005;79:1393–1400. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000164146.21136.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centurion SA, Centurion LM, Souza ME, Gomes MC, Sankarankutty AK, Mente ED, et al. Effects of ischaemic liver preconditioning on hepatic ischaemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niemann CU, Hirose R, Liu T, Behrends M, Brown JL, Kominsky DF, et al. Ischaemic preconditioning improves energy state and transplantation survival in obese Zucker rat livers. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1577–1583. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000184897.53609.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi S, Noh J, Hirose R, Ferell L, Bedolli M, Roberts JP, et al. Mild hypothermia provides significant protection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury in livers of obese and lean rats. Ann Surg. 2005;241:470–476. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154259.73060.f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapuria N, Junnarkar S, Dutt N, Abu AM, Fuller B, Seifalian AM, et al. Effect of remote ischaemic preconditioning on hepatic microcirculation and function in a rat model of hepatic ischaemia reperfusion injury. HPB. 2009;11:108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanoria S, Jalan R, Davies NA, Seifalian AM, Williams R, Davidson BR. Remote ischaemic preconditioning of the hind limb reduces experimental liver warm ischaemia–reperfusion injury. Br J Surg. 2006;93:762–768. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe K, Koizumi F, Kurashige Y, Tsurufuji S, Nakagawa H. Rat CINC, a member of the interleukin-8 family, is a neutrophil-specific chemoattractant in vivo. Exp Mol Pathol. 1991;55:30–37. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(91)90016-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hisama N, Yamaguchi Y, Ishiko T, Miyanari N, Ichiguchi O, Goto M, et al. Kupffer cell production of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant following ischaemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Hepatology. 1996;24:1193–1198. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008903397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamanouchi K, Eguchi S, Kamohara Y, Yanaga K, Okudaira S, Tajima Y, et al. Glycine reduces hepatic warm ischaemia–reperfusion injury by suppressing inflammatory reactions in rats. Liver Int. 2007;27:1249–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonezawa K, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Ishikawa Y, Uchinami H, Taura K, et al. Suppression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha production and neutrophil infiltration during ischaemia–reperfusion injury of the liver after heat shock preconditioning. J Hepatol. 2001;35:619–627. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koti RS, Seifalian AM, McBride AG, Yang W, Davidson BR. The relationship of hepatic tissue oxygenation with nitric oxide metabolism in ischaemic preconditioning of the liver. FASEB J. 2002;16:1654–1656. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-1034fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristiansen SB, Henning O, Kharbanda RK, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Schmidt MR, Redington AN, et al. Remote preconditioning reduces ischaemic injury in the explanted heart by a KATP channel-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1252–H1256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00207.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto M, Liu Y, Yang XM, Ardell JL, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Role of bradykinin in protection of ischaemic preconditioning in rabbit hearts. Circ Res. 1995;77:611–621. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vollmar B, Glasz J, Post S, Menger MD. Role of microcirculatory derangements in manifestation of portal triad cross-clamping-induced hepatic reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 1996;60:49–54. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brock RW, Carson MW, Harris KA, Potter RF. Microcirculatory perfusion deficits are not essential for remote parenchymal injury within the liver. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:55–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.1.G55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollmar B, Richter S, Menger MD. Liver ischaemia/reperfusion induces an increase of microvascular leukocyte flux, but not heterogeneity of leukocyte trafficking. Liver. 1997;17:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1997.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerhackl B, Parekh N, Brinkhus H, Steinhausen M. The use of fluorescent labelled erythrocytes for intravital investigation of flow and local haematocrit in glomerular capillaries in the rat. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1983;2:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wunder C, Brock RW, McCarter SD, Bihari A, Harris K, Eichelbronner O, et al. Inhibition of haemoxygenase activity increases leukocyte accumulation in the liver following limb ischaemia–reperfusion in mice. J Physiol. 2002;540:1013–1021. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.015446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glanemann M, Vollmar B, Nussler AK, Schaefer T, Neuhaus P, Menger MD. Ischaemic preconditioning protects from hepatic ischaemia/reperfusion injury by preservation of microcirculation and mitochondrial redox-state. J Hepatol. 2003;38:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terajima H, Enders G, Thiaener A, Hammer C, Kondo T, Thiery J, et al. Impact of hyperthermic preconditioning on post-ischaemic hepatic microcirculatory disturbances in an isolated perfusion model of the rat liver. Hepatology. 2000;31:407–415. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moses MA, Addison PD, Neligan PC, Ashrafpour H, Huang N, Zair M, et al. Mitochondrial KATP channels in hind limb remote ischaemic preconditioning of skeletal muscle against infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H559–H567. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addison PD, Neligan PC, Ashrafpour H, Khan A, Zhong A, Moses M, et al. Non-invasive remote ischaemic preconditioning for global protection of skeletal muscle against infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:1435–1443. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00106.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]