Abstract

There are two well-defined neurogenic regions in the adult brain, the subventricular zone (SVZ) lining the lateral wall of the lateral ventricles and, the subgranular zone (SGZ) in the dentate gyrus at the hippocampus. Within these neurogenic regions, there are neural stem cells with astrocytic characteristics, which actively respond to the basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, FGF2 or FGF-β) by increasing their proliferation, survival and differentiation, both in vivo and in vitro. FGF2 binds to fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 to 4 (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4). Interestingly, these receptors are differentially expressed in neurogenic progenitors. During development, FGFR-1 and FGFR-2 drive oligodendrocytes and motor neuron specification. In particular, FGFR-1 determines oligodendroglial and neuronal cell fate, whereas FGFR-2 is related to oligodendrocyte specification. In the adult SVZ, FGF-2 promotes oligodendrogliogenesis and myelination. FGF-2 deficient mice show a reduction in the number of new neurons in the SGZ, which suggests that FGFR-1 is important for neuronal cell fate in the adult hippocampus. In human brain, FGF-2 appears to be an important component in the anti-depressive effect of drugs. In summary, FGF2 is an important modulator of the cell fate of neural precursor and, promotes oligodendrogenesis. In this review, we describe the expression pattern of FGFR2 and its role in neural precursors derived from the SVZ and the SGZ.

Keywords: Neural stem cells, basic fibroblast growth factor, fibroblast growth factor receptor, subventricular zone, subgranular zone, astrocyte, glia

Introduction

In the adult mammalian brain discrete proliferative regions exist that throughout life produce new neurons. These cerebral areas are commonly known as neurogenic niches, which provide a microenvironment and a very particular cytoarchitecture to preserve the cell proliferation and survival of neural stem cells [1]. The most well-accepted neurogenic niches in the adult brain are the subventricular zone (SVZ), lining the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle [2], and the subgranular zone (SGZ) located in the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus [3]. Remarkably, the neural stem cells in the SVZ and the SGZ are a subpopulation of astrocytes, which derived from the embryonic radial glia [4, 5]. During development, radial glia generates neurons and glia [6, 7]. In the adult human brain, neural stem cells have been successfully isolated [8], but the precise role of these progenitors and their progeny has not been elucidated, yet [9].

During embryonic development of CNS, FGF2 promotes differentiation of neural cells in different brain regions [10]. In adulthood, astrocytic neural stem cells, located in the SVZ and the SGZ also produces neurons and glial cells in response to a number of cytokines, including the basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, FGF-2 or FGF-β) [11, 12]. In the central nervous system (CNS), FGF2 is produced by glial cells [13] and binds to four different types of receptors: FGFR-1, FGFR-2, FGFR-3 y FGFR-4 [14]. Interestingly, FGFRs are differentially expressed in the neural progenitors of the SGZ and the SVZ [15]. The role of FGFR subtypes in these neurogenic regions and adult progenitor cells is still unclear [16]. However, it is known that FGF2 induces high proliferation rate in cell cultures and, depending on cell culture conditions, promotes neuronal [17] or glial differentiation [18]. These differential effects may be due to different FGFR-subtype expression, as well as regional properties of neural progenitors in the SVZ and SGZ. In this review, we summarize the role of FGF-2 on neural stem cells resident in the SVZ and the SGZ and, its potential role in regenerative processes.

Neurogenic regions in the adult brain

The SVZ is adjacent to the lateral wall of the lateral ventricles [2]. Neural stem cells in this region are a subpopulation of SVZ astrocytes, also known as type-B1 cells [19]. Type-B1 astrocytes produce ‘transit amplifying progenitor cells’ (type-C cells). Cell differentiation of type-C cells give origin to neuroblasts referred to as type-A cells, which migrate tangentially through the ‘rostral migratory stream’ (RMS) [19]. Upon reaching the rodent olfactory bulb, migrating neuroblasts spread and populate the granular and periglomerular layers [20]. The function of these novel interneurons is unclear, but it seems they are implicated in odor discriminating tasks [21].

The SGZ is located in the dentate gyrus of adult hippocampus. In this region, radial astrocytes, also known as type-B cells or type-1 progenitors, function as neuronal progenitors in vivo [22]. SGZ radial astrocytes divide and give rise to “dark” cells referred to as type-D1 cells. Subsequent progeny of type-D1 cells are type-D2 and type-D3 cells [3]. Type-D3 cells display morphology of immature granular neurons and express several neuronal markers [12]. Further differentiation of type-D3 cells give origin to mature granular neurons, which incorporate into local neuronal circuits within the hippocampus [3, 23]. Interestingly, new-born neurons in the dentate gyrus appear to play a role in learning-memory processes [24] and depression syndrome [25].

Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2)

The family of FGF comprises twenty three peptides. Member of this family play important roles during neural development by modulating proliferation, migration, angiogenesis and chemoattractant activity [26]. In the adult brain, FGF promotes wound recovery, increases proliferation and enhances development and progression of brain tumors [27, 28]. FGF-2 has a molecular weight of 18 kDa, but a 24-kDa FGF-2 isoform has also been described [27]. The 18-kDa FGF-2 isoform is located in the cytosol, whereas 24-kDa isoform is found into the nucleus [27]. It is thought that FGF-2 is one of the first mitogen factors expressed during neural development, but other member of this family, such as FGF-1, FGF-5 and FGF-8 also participate in embryonic brain development [29]. In the whole body, the main endogenous sources of FGF-2 are endothelium, smooth muscle and fibroblasts [30]. In the brain, the main source of FGF2 is glial cells, in particular mature astrocytes [13]. FGF-2 can signal through paracrine and autocrine mechanisms [13, 30]. This growth factor also modulates pituitary functioning by regulating prolactin synthesis [31] and, promotes angiogenesis and tumor development. These effects appear to be mediated by inducing endothelium to produce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or by promoting synthesis of chemokines and cytokines, such as, interleukin-1 (IL-1) interleukin-8 (IL-8) and tumor neural factor alpha (TNF-α), which activates Ras/Raf/MAPK1 pathways [26]. After a brain injury, FGF-2 increases the levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [32] and enhances astrocyte reactivity [13]. In turn, reactive astrocytes appear to promote neurogenesis in the adult brain [33].

FGFR expression in neural stem cell

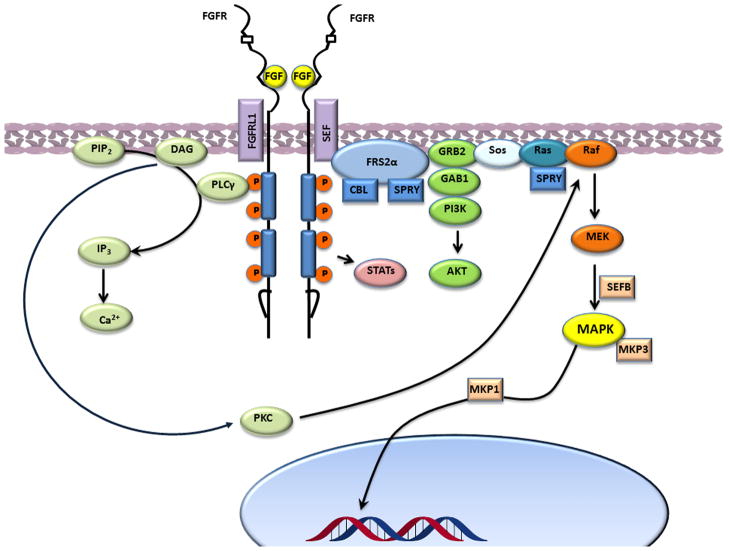

Neurogenic glia are the primary source of FGF-2 that binds to four different receptors (FGFR-1, FGFR-2, FGFR-3 y FGFR-4) [34] with two transmembrane domains (Figure 1). FGFR is constituted by: 1) an extracellular domain with two or three immunoglobulin-like peptides plus a hydrophilic heparine-binding domain, 2) a transmembrane region and, 3) an intracellular tyrosine-kinase-like domain [28]. Following ligand binding and FGFR dimerization, the kinase domains phosphorylate each other, leading to the docking of adaptor proteins and the activation of RAS–RAF–MAPK and PI3K–AKT downstream pathways [35](Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways of the fibroblast growth factor receptor in neural stem cells. In the MAPK (also known as ERK) pathway, activated receptors lead to activation of RAS and signal through RAF, MEK (also known as MAP2K) and MAPK.

Heparan sulphate epitopes are important for binding FGFR ligands and appear to control neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells [36]. FGF-2 strongly regulates the function of neural stem cells in both the embryo and adult brain.

During development, FGFRs begin to be expressed at E12.5 in the CNS. FGFR-1, FGFR-2 and FGFR-3 are initially expressed in ventral regions of the ventricular zone [18]. Inhibition of FGF in neuroectodermal stem cells blocks ERK1/2 and reduces Pax-6 transcription factor [37]. Pax-6 is associated with neuronal differentiation during embryonic development and adult neurogenesis in the SVZ and the SGZ [38]. Therefore, FGF-2-induced neuronal differentiation appears to be mediated through ERK1/2 pathway. Mice lacking FGFR-1 and FGFR-2 show an important reduction in oligodendrocytes and motor neurons in the developing spinal cord [18]. FGFR-1 drives both oligodendroglial and neuronal cell fate and is also involved in axonal growth of sensorial neurons [39]. Mutant mice lacking FGFR-1 show a decrease in radial glia and oligodendroglial progenitors [40]. On the other hand, FGFR-2 is essential for oligodendrocyte specification, but not for neuronal production [18]. Mutations on FGFR-3 expression have none of these effects [18]

In neuronal-glial cocultures from the embryonic rat ventral midbrain, FGF-2 helps maintain proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cell into dopaminergic neurons. [13]. Administration of FGF-2 in vivo drives neural progenitors into the oligodendroglial lineage. A short exposure to FGF-2 in cell cultures of cortical glutamatergic neurons (Pax6+/Mash1+/Ngn2+) induces a GABAergic phenotype and oligodendroglial lineage [41]. This cellular specification in ventral brain regions is mediated by Olig-2 and Mash-1 transcription factors, which is associated with an increase in bone morphogenetic protein-4 levels (BMP-4) and a reduction in noggin [41]. On this regard, the phosphorylation of Ngn2 at serine residues S231 and S234 promotes the interaction of Ngn2 with LIM homeodomain transcription factors to specify motor neuron identity [42]. Therefore, high levels of phospho-GSK-3β activated through FGFRs are important cell components to promote the neuronal lineage [43]. In summary, the higher expression of PI3K/Akt, the lesser GSK-3β level and neuronal differentiation.

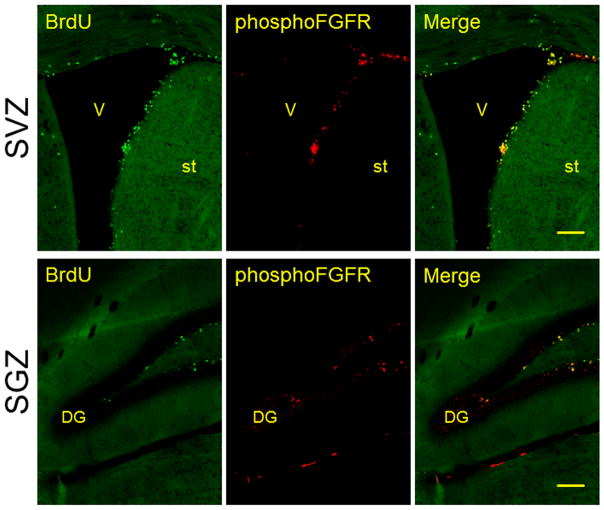

In the adult brain, FGFR and phosphorylated FGFR (phospho-FGFR) are highly expressed in neurogenic niches. In fact, phospho-FGFRs are strongly expressed by dividing neural progenitors in both the SVZ and the SGZ (Figure 2). FGFR-1, FGFR-2 and FGFR-3 are initially expressed in ventral regions of the ventricular zone [18]. By in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, FGFR-1 and FGFR-2 were described in dividing SVZ neural progenitors, whereas FGFR-3 was only found by non-proliferative SVZ cells [15]. Similar findings have been described in along the RMS in migratory neuronal precursors [44]. Axonal growth mediated by FGF-2 signaling appears to be regulated via receptor degradation. Upon FGFR-1 is activated by its ligand, it is endocytosed and degraded by lysozymes, which controls axonal growth [39]. Sprouty (Spred 1 y 2) and Mkp/Dusp transcription factors regulate the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) by proteasome ubiquitination upon interaction between FRS2 and E3 proteins [26]. Therefore, these proteins might regulate the FGFR signaling pathway in adult neural stem cells. FGF-2 has a synergistic effect with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) producing an important increase in oligodendrogenesis mediated by mitogenic effects of cyclin D1 [45]. In this case, FGF-2 induces ERK1 (p44) and ERK2 (p42) phosphorylation, allowing cyclin D1 to enter in the S-phase of cell cycle, whereas IGF-1 stabilizes cyclin D1 by activating Akt/PI3k pathway [45]. Phosphorylated Akt overexpression is associated with myelination in white matter tracts, but not with proliferation or cell survival [46]. Activation of EGFR and FGFR can activate PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway that, in turn, negatively regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β). EGFR stimulation induces SVZ multipotencial astrocytes to produce oligodendrocyte progenitors and decreases the neurogenesis rate [47–49].

Figure 2.

Expression of phosphorylated FGFR (phospho-FGFR) in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the subgranular zone (SGZ). Note that most of the proliferative cells (BrdU+ cells) co-express phospho-FGFR. V: Ventricle; st: Striatum; DG: Dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 100 μm.

In contrast, SGZ progenitors in dentate gyrus seem to express FGFR-1 only [15]. The precise role of FGF2 in dentate gyrus is still not well-understood. Radial astrocytes in the SGZ express FGFR-1 [15]. FGF-2 deficient mice do not show obvious changes in the number of neuronal precursor in the SGZ, but a reduction in the number of new neurons, which suggests that FGFR-1 is important for neuronal cell fate [16]. These changes may be due to down-regulation of Pax-6, a transcriptional factor expressed by stem cells in this region and associated with neuronal differentiation [38].

Increasing evidence indicates that the immune system can regulate the proliferation, differentiation and migration of adult neural stem cells [50, 51]. Thus, it has been proposed that a number of trophic and morphogenic factors control the function of human neural stem cells [52]. FGF-2 induces proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells isolated from the adult SVZ [8]. The function of FGF-2 in vivo has not been elucidated in the human brain, but some evidence indicates that several members of FGF family might be implicated in the pathogenesis of major depression and Alzheimer’s disease [53–55]. Thus, FGF2 gene transfer has recently been found to restore hippocampal functions in a model of Alzheimer’s disease, partly as a result of enhanced neurogenesis [56]. FGF-2 levels are increased by antidepressant treatment. In fact, FGF-2 treatment increases neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus and reduces depressive-like behavior induced by bulbectomy in rodents [53]. This suggests that FGF-2 is an important component in the antidepressive effect of drugs and in the SGZ neurogenesis.

Conclusion

FGF-2 it is one of the most important growth factor that regulates cell activity in neurogenic niches by acting through FGFRs (1, 2, 3 and 4). These four receptors are expressed in different cells within the SVZ and SGZ and, probably, activate different intracellular signaling pathways. Understanding cellular mechanisms activated by FGFR on astrocytic neural stem cells and their intracellular signaling pathways will contribute to the design of stem-cell- or gene-transfer-based therapies against neurodegenerative disorders [55, 57–60].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT; CB-2008-101476) and The National Institute of Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS; R01 NS070024).

References

- 1.Mackay-Sim A. Stem cells and their niche in the adult olfactory mucosa. Arch Ital Biol. 2010 Jun;148(2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F, Wichterle H, Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Architecture and cell types of the adult subventricular zone: in search of the stem cells. J Neurobiol. 1998 Aug;36(2):234–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199808)36:2<234::aid-neu10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Collado-Morente L, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cell types, lineage, and architecture of the germinal zone in the adult dentate gyrus. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2004 Oct 25;478(4):359–78. doi: 10.1002/cne.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merkle FT, Tramontin AD, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Radial glia give rise to adult neural stem cells in the subventricular zone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004 Dec 14;101(50):17528–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407893101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonfanti L, Peretto P. Radial glial origin of the adult neural stem cells in the subventricular zone. Prog Neurobiol. 2007 Sep;83(1):24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto L, Gotz M. Radial glial cell heterogeneity--the source of diverse progeny in the CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 2007 Sep;83(1):2–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004 Feb 19;427(6976):740–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinones-Hinojosa A, Sanai N, Gonzalez-Perez O, Garcia-Verdugo JM. The human brain subventricular zone: stem cells in this niche and its organization. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2007 Jan;18(1):15–20. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens HE, Smith KM, Maragnoli ME, Fagel D, Borok E, Shanabrough M, et al. Fgfr2 is required for the development of the medial prefrontal cortex and its connections with limbic circuits. J Neurosci. 2010 Apr 21;30(16):5590–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5837-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gritti A, Frolichsthal-Schoeller P, Galli R, Parati EA, Cova L, Pagano SF, et al. Epidermal and fibroblast growth factors behave as mitogenic regulators for a single multipotent stem cell-like population from the subventricular region of the adult mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 1999 May 1;19(9):3287–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03287.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M. Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2005 Apr;85(2):523–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuss B, Dermietzel R, Unsicker K. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) differentially regulates connexin (cx) 43 expression and function in astroglial cells from distinct brain regions. Glia. 1998 Jan;22(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dvorak P, Hampl A. Basic fibroblast growth factor and its receptors in human embryonic stem cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2005;43(4):203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frinchi M, Bonomo A, Trovato-Salinaro A, Condorelli DF, Fuxe K, Spampinato MG, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and its receptor expression in proliferating precursor cells of the subventricular zone in the adult rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2008 Dec 5;447(1):20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner S, Unsicker K, von Bohlen und Halbach O. Fibroblast growth factor-2 deficiency causes defects in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, which are not rescued by exogenous fibroblast growth factor-2. J Neurosci Res. 2011 Oct;89(10):1605–17. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH. Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997 Aug 1;17(15):5820–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furusho M, Kaga Y, Ishii A, Hebert JM, Bansal R. Fibroblast growth factor signaling is required for the generation of oligodendrocyte progenitors from the embryonic forebrain. J Neurosci. 2011 Mar 30;31(13):5055–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4800-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim DA, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999 Jun 11;97(6):703–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lie DC, Song H, Colamarino SA, Ming GL, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: new strategies for central nervous system diseases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:399–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gheusi G, Cremer H, McLean H, Chazal G, Vincent JD, Lledo PM. Importance of newly generated neurons in the adult olfactory bulb for odor discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Feb 15;97(4):1823–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonaguidi MA, Wheeler MA, Shapiro JS, Stadel RP, Sun GJ, Ming GL, et al. In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell. 2011 Jun 24;145(7):1142–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:223–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin-Burgin A, Schinder AF. Requirement of adult-born neurons for hippocampus-dependent learning. Behav Brain Res. 2011 Jul 7; doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt HD, Duman RS. The role of neurotrophic factors in adult hippocampal neurogenesis, antidepressant treatments and animal models of depressive-like behavior. Behav Pharmacol. 2007 Sep;18(5–6):391–418. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282ee2aa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acevedo VD, Ittmann M, Spencer DM. Paths of FGFR-driven tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2009 Feb 15;8(4):580–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.4.7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000 Sep;7(3):165–97. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chadashvili T, Peterson DA. Cytoarchitecture of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR-2) immunoreactivity in astrocytes of neurogenic and non-neurogenic regions of the young adult and aged rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006 Sep 1;498(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/cne.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalyani AJ, Mujtaba T, Rao MS. Expression of EGF receptor and FGF receptor isoforms during neuroepithelial stem cell differentiation. J Neurobiol. 1999 Feb 5;38(2):207–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein S, Morimoto T, Rifkin DB. Characterization of fibroblast growth factor-2 binding to ribosomes. Growth Factors. 1996;13(3–4):219–28. doi: 10.3109/08977199609003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimura K, Kaji H, Kamidono S, Chihara K. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) messenger ribonucleic acid is regulated by testosterone in the rat anterior pituitary. Growth Factors. 1994;10(4):253–8. doi: 10.3109/08977199409010991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahmy GH, Moftah MZ. Fgf-2 in astroglial cells during vertebrate spinal cord recovery. Front Cell Neurosci. 2010;4:129. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2010.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estrada FS, Hernandez VS, Medina MP, Corona-Morales AA, Gonzalez-Perez O, Vega-Gonzalez A, et al. Astrogliosis is temporally correlated with enhanced neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus following a glucoprivic insult. Neuroscience letters. 2009 Aug 14;459(3):109–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frinchi M, Di Liberto V, Olivieri M, Fuxe K, Belluardo N, Mudo G. FGF-2/FGFR1 neurotrophic system expression level and its basal activation do not account for the age-dependent decline of precursor cell proliferation in the subventricular zone of rat brain. Brain Res. 2010 Oct 28;1358:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coutu DL, Galipeau J. Roles of FGF signaling in stem cell self-renewal, senescence and aging. Aging. 2011 Oct;3(10):920–33. doi: 10.18632/aging.100369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pickford CE, Holley RJ, Rushton G, Stavridis MP, Ward CM, Merry CL. Specific glycosaminoglycans modulate neural specification of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2011 Apr;29(4):629–40. doi: 10.1002/stem.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo Y, Huang C, Zhang X, Lavaute TM, Zhang SC. Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Regulates Human Neuroectoderm Specification Through ERK1/2-PARP-1 Pathway. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2011 Oct 13; doi: 10.1002/stem.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osumi N, Shinohara H, Numayama-Tsuruta K, Maekawa M. Concise review: Pax6 transcription factor contributes to both embryonic and adult neurogenesis as a multifunctional regulator. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2008 Jul;26(7):1663–72. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausott B, Rietzler A, Vallant N, Auer M, Haller I, Perkhofer S, et al. Inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 endocytosis promotes axonal branching of adult sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2011 Aug 11;188:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seth P, Koul N. Astrocyte, the star avatar: redefined. J Biosci. 2008 Sep;33(3):405–21. doi: 10.1007/s12038-008-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bithell A, Finch SE, Hornby MF, Williams BP. Fibroblast growth factor 2 maintains the neurogenic capacity of embryonic neural progenitor cells in vitro but changes their neuronal subtype specification. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2008 Jun;26(6):1565–74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma YC, Song MR, Park JP, Henry Ho HY, Hu L, Kurtev MV, et al. Regulation of motor neuron specification by phosphorylation of neurogenin 2. Neuron. 2008 Apr 10;58(1):65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ojeda L, Gao J, Hooten KG, Wang E, Thonhoff JR, Dunn TJ, et al. Critical role of PI3K/Akt/GSK3beta in motoneuron specification from human neural stem cells in response to FGF2 and EGF. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Gonzalez D, Clemente D, Coelho M, Esteban PF, Soussi-Yanicostas N, de Castro F. Dynamic roles of FGF-2 and Anosmin-1 in the migration of neuronal precursors from the subventricular zone during pre- and postnatal development. Experimental neurology. 2011 Apr;222(2):285–95. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frederick TJ, Min J, Altieri SC, Mitchell NE, Wood TL. Synergistic induction of cyclin D1 in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells by IGF-I and FGF-2 requires differential stimulation of multiple signaling pathways. Glia. 2007 Aug 1;55(10):1011–22. doi: 10.1002/glia.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flores AI, Narayanan SP, Morse EN, Shick HE, Yin X, Kidd G, et al. Constitutively active Akt induces enhanced myelination in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2008 Jul 9;28(28):7174–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0150-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Perez O, Alvarez-Buylla A. Oligodendrogenesis in the subventricular zone and the role of epidermal growth factor. Brain research reviews. 2011 Jun 24;67(1–2):147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez-Perez O, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Dose-dependent effect of EGF on migration and differentiation of adult subventricular zone astrocytes. Glia. 2010 Jun;58(8):975–83. doi: 10.1002/glia.20979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Perez O, Romero-Rodriguez R, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Epidermal growth factor induces the progeny of subventricular zone type B cells to migrate and differentiate into oligodendrocytes. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2009 Aug;27(8):2032–43. doi: 10.1002/stem.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez-Perez O, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Immunological control of adult neural stem cells. Journal of stem cells. 2010;5(1):23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez-Perez O, Jauregui-Huerta F, Galvez-Contreras AY. Immune system modulates the function of adult neural stem cells. Current immunology reviews. 2010 Aug 1;6(3):167–73. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alvarez-Palazuelos LE, Robles-Cervantes MS, Castillo-Velazquez G, Rivas-Souza M, Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Luquin S, et al. Regulation of neural stem cell in the human SVZ by trophic and morphogenic factors. Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):320–6. doi: 10.2174/157436211797483958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarosik J, Legutko B, Werner S, Unsicker K, von Bohlen Und Halbach O. Roles of exogenous and endogenous FGF-2 in animal models of depression. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29(3):153–65. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2011-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takebayashi M, Hashimoto R, Hisaoka K, Tsuchioka M, Kunugi H. Plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2 in patients with major depressive disorders. J Neural Transm. 2010 Sep;117(9):1119–22. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Galvez-Contreras AY, Luquin S, Gonzalez-Perez O. Neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease: a realistic alternative to neuronal degeneration? Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):314–9. doi: 10.2174/157436211797483949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiyota T, Ingraham KL, Jacobsen MT, Xiong H, Ikezu T. FGF2 gene transfer restores hippocampal functions in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and has therapeutic implications for neurocognitive disorders; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2011. Oct 31, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rivera FJ, Kraus J, Steffenhagen C, Kury P, Weidner N, Aigner L. Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis: The Therapeutic Potential of Neural and Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cells. Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):293–313. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitrecic D, Nicaise C, Gajovic S, Pochet R. The Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):341–6. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kasahara Y, Nakagomi T, Nakano-Doi A, Matsuyama T, Taguchi A. The Therapeutic Potential of Neural Stem Cells in Cerebral Ischemia. Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):347–52. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kabatas S, Cansever TEC, Yilmaz C. The Therapeutic Potential of Neural Stem Cells in Traumatic Brain Injuries. Current signal transduction therapy. 2011 Sep 1;6(3):327–36. [Google Scholar]