Abstract

Background:

Significant advances in surgical techniques and postsurgical care have been made in the last 10 years. The goal of this study was to evaluate any decline in the age‐adjusted in‐hospital mortality rate of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using a national database from 1989 to 2004 in the United States.

Hypothesis:

Reduction in CABG related mortality in recent years.

Methods:

Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, we obtained specific ICD‐9‐CM codes for CABG to compile the data. To exclude nonatherosclerotic cause of coronary disease, we studied only patients older than 40 years. We calculated total and age‐adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 for this period.

Results:

The NIS database contained 1 145 285 patients who had CABG performed from 1988 to 2004. The mean age for these patients was 71.05 ± 9.20 years. From 1989, the age‐adjusted rate for all CABG‐related mortality has been decreasing steadily and reached the lowest level in 2004: 300.3 per 100 000 in 1989, (95% confidence interval [CI], 20.4‐575.9) and 104.69 per 100 000 (95% CI, 22.6‐186.7) in 2004. Total death also declined from 5.5% to 3.06%. This decline occurred irrespective of comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, or acute myocardial infarction, albeit increasing the number of CABG procedures performed in high‐risk patients.

Conclusions:

The age‐adjusted in‐hospital mortality rate from CABG has been declining steadily and reached its lowest level in 2004, irrespective of comorbidities. This decline most likely reflects advances in surgical techniques and the use of evidence‐based medicine in patients undergoing CABG. Clin. Cardiol. 2011 DOI: 10.1002/clc.21970

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and worldwide. Nearly 17 million have coronary artery disease (CAD), which causes up to 500 000 deaths a year.1 Revascularization with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was developed in the 1960s and has been extensively used in patients with 3‐vessel or left main disease.2., 3., 4. CABG‐related mortality has been influenced by various factors.5., 6., 7. Significant advances in surgical techniques and postsurgical care have been made in the last 10 years. We have shown that advancement in the multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention technology most likely has lead to increasing utilization of this procedure,8 with declining procedure‐related mortality.9 This has led to a gradual decline in the rate of CABG performed in the United States in recent years.10 We hypothesize that improvement in the surgical technology and the use of evidence‐based medical care such as statins and preoperative β‐blockers used during the postoperative period in patients undergoing CABG should lead to lower CABG‐related mortality. The goal of this study was to evaluate age‐adjusted CABG‐related in‐hospital mortality using a very large nationwide database from 1989 to 2004 in the United States.

Methods

Data Source

The National Inpatient sample (NIS) is a major database of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Policymakers and researchers use the NIS to identify, track, and analyze national trends in healthcare utilization, access, charges, quality, and outcomes. NIS represents nearly a 20% sample of all short‐term, general, and specialty hospitals in the United States and excludes data elements that could directly or indirectly identify individuals, thus making the data anonymous. In some situations identities of institutions are available only in states where data sources already make that information public or agree to its release. NIS collects information on primary and secondary diagnosis and procedures, discharge status, and demographics on more than 7 million discharges per year.

Sample Selection

We obtained specific ICD‐9‐CM codes for CABG to compile the data. We used the primary code for CABG as follows: 36.10, 36.11, 36.12, 36.13, 36.14, 36.15, 36.16, 36.17, and 36.19 from the years 1988 to 2004. To exclude nonatherosclerotic causes of coronary disease, we studied only patients more than 40 years old. We calculated total and age‐adjusted mortality rate per 100 000 for this period. We did not include patients undergoing valve surgery in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The average annual age‐adjusted CABG‐related in‐hospital mortality rates along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for each year for the entire cohort and in patients with congestive heart failure, diabetes, and ST‐elevation and non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction by weighted average of the age‐specific (crude) rates. The weights are the proportions of persons in the corresponding age groups of a standard population. We used the proportion of the year 2000 standard U.S. population within each age group for the age adjustment of the data. The weighted rates were then summed across the age groups to give the age‐adjusted rate for each year from 1998 to 2004. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used to calculate CABG‐related age‐adjusted mortality rate. Furthermore, we evaluated age‐adjusted CABG rate in this population based on comorbidities. Quantitative variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

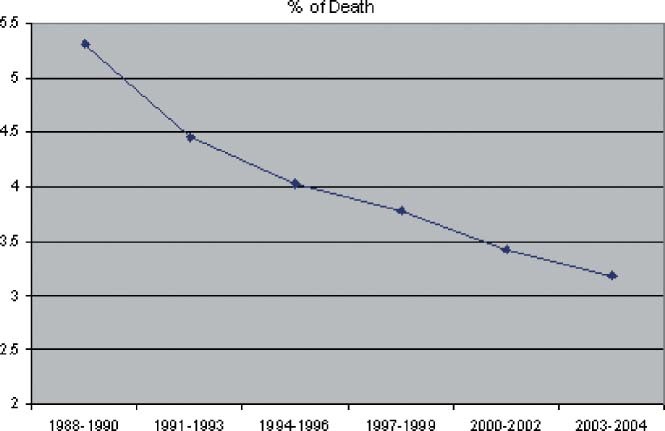

The NIS database contained 1 145 285 patients who had CABG performed from 1988 to 2004. The mean age for these patients was 71.05 ± 9.20 years. From 1989, the age‐adjusted rate for all CABG‐related mortality has been decreasing steadily and reached the lowest level in 2004: 300.3 per 100 000 in 1989 (95% CI, 20.4‐575.9) and 104.69 per 100 000 (95% CI, 22.6‐186.7) in 2004 (Figure 1). Total death also declined from 5.5% to 3.06% (Figure 2). This decline occurred irrespective of comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or acute myocardial infarction (Figure 3). However, this decline reached a plateau in recent years. Interestingly, this decline occurred despite an increasing rate of CABG performed in high‐risk patients such as patients with diabetes or congestive heart failure in the recent years studied (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Steady decline in the age‐adjusted coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)‐related in‐hospital mortality in recent years.

Figure 2.

Steady decline in the coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)‐related total mortality in recent years.

Figure 3.

Steady decline in the age‐adjusted coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)‐related mortality irrespective of comorbidities. DM, type 2 diabetes; CHF, congestive heart failure; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction; Non STEMI, non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure 4.

Gradual increase in the age‐adjusted rate of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) performed in high‐risk patients in recent years, except in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). DM, type 2 diabetes; CHF, congestive heart failure; Non STEMI, non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction.

Discussion

We found a significant decrease in CABG‐related in‐hospital mortality, with the lowest level reached in 2004 across the United States. Furthermore, this decline was irrespective of comorbidities, despite higher rates of CABG performed in high‐risk patients. Our study results are consistent with those of previous studies showing the improvements in mortality outcome.11., 12., 13., 14. The cause of this decline most likely reflects advancement in surgical techniques, medical treatment, and postsurgical care. For example, procedures such as off‐pump surgeries are being used more commonly. Minimally invasive techniques using thoracoscopic, robotic CABG and arterial grafts have gained increased popularity.15 Consistent with our results, a recent study from Canada on octogenarians getting CABG revealed a decrease in in‐hospital mortality from 7.1% (1990–1999) to 3.2% (2000–2005, P = 0.02).16 This was attributed to the use of intra‐aortic balloon pump and lower stroke rates over time. A recent multicenter study revealed significantly lower requirement for intraoperative or postoperative intra‐aortic balloon pump insertion, lower rate of postoperative atrial fibrillation, and a shorter length of stay in patients undergoing off‐pump CABG.17 Improvements in surgical techniques in regards to myocardial protection, revascularization, and anesthetic management have contributed to favorite outcome in diabetes patients undergoing CABG.18 The recent introduction of the surgical safety checklist by the World Health Organization has provided a well‐validated and inexpensive way of helping in reduction of human error in CABG patients, with improvements in teamwork and communication.19 Advances in using atraumatic surgical techniques to minimize vascular damage during vein harvesting could lead to better graft patency and contribute to better outcome.20

The use of evidence‐based medications including antiplatelet drugs, β‐blockers, and statins may have also contributed to the improvement in survival. In the treatment of acute coronary syndrome, antiplatelet therapy plays a major role.21 A prospective study demonstrated reduction in myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality when aspirin was given within 48 hours of CABG. Another study has demonstrated that a combination of clopidogrel and aspirin is superior to aspirin alone in the setting of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).22., 23. Two studies demonstrated that preoperative statin therapy reduces the occurrence of myocardial infarction and also increases survival.24., 25. Advances in the care of patients with diabetes including improvement in hyper‐ or hypoglycemia during and after hospital stay are other important factors for better outcome.26 Significant accelerated drop in the age‐adjusted mortality from the period 1988 to 1990 to the period 1991 to 1993 with slower decline from 1993 onward could have been related to the inception of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk model in 1991, leading to better patient selection during those years.27

Conclusion

The age‐adjusted in‐hospital mortality rate from CABG has been declining steadily and reached its lowest level in 2004, irrespective of comorbidities. The cause of this decline most likely reflects advancement in surgical techniques and recent advances in the use of evidence‐based medicine in patients undergoing CABG. Despite increasing complexity of patients undergoing CABG seen in our study, declining trend in in‐hospital mortality, irrespective of comorbidities, is very encouraging.

Limitations

We used the ICD‐9 code with inherent inaccuracy. However, the large number of patients involved in this study offset any inaccuracy in the ICD‐9 coding. Changes in the ICD‐9 coding over the years could influence the CABG rate. However, ICD‐9 coding for CABG has not undergone many changes in recent years. We did not have any information about medications used; therefore, we could not evaluate the effect of medication on mortality. This is a retrospective data analysis of crude data that is hypothesis generating and needs to be confirmed by future studies.

References

- 1. Lloyd‐Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronary artery surgery study (CASS): a randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Quality of life in patients randomly assigned to treatment groups. Circulation. 1983;68:951–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronary artery surgery study (CASS): a randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Survival data. Circulation. 1983;68:939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alderman EL, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Results of coronary artery surgery in patients with poor left ventricular function (CASS). Circulation. 1983;68:785–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tarantini G, Ramondo A, Napodano M, et al. PCI versus CABG for multivessel coronary disease in diabetics. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodes‐Cabau J, Deblois J, Bertrand OF, et al. Nonrandomized comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in octogenarians. Circulation. 2008;118:2374–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kohsaka S, Goto M, Virani S, et al. Long‐term clinical outcome of coronary artery stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with multiple‐vessel disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Movahed MR, Ramaraj R, Jamal MM, et al. Nationwide trends in the utilization of multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention (MVPCI) in the United States across different gender and ethnicities. J Interv Cardiol. 2009;22:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Movahed MR, Ramaraj R, Jamal MM, et al. Decline in the nationwide trends in in‐hospital mortality of patients undergoing multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:388–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Khoynezhad A, et al. Sex‐ and ethnic group‐specific nationwide trends in the use of coronary artery bypass grafting in the United States. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1545–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pell JP, Walsh D, Norrie J, et al. Outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in the stent era: a prospective study of all 9890 consecutive patients operated on in Scotland over a two year period. Heart. 2001;85:662–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ugnat AM, Naylor CD. Trends in coronary artery bypass grafting in Ontario from 1981 to 1989. CMAJ. 1993;148:569–575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCaul KA, Hobbs MS, Knuiman MW, et al. Trends in two year risk of repeat revascularisation or death from cardiovascular disease after coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention in Western Australia, 1980–2001. Heart. 2004;90:1042–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blackledge HM, Squire IB. Improving long‐term outcomes following coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary revascularisation: results from a large, population‐based cohort with first intervention 1995–2004. Heart. 2009;95:304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. King Iii SB, Marshall JJ, Tummala PE. Revascularization for coronary artery disease: stents versus bypass surgery. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maganti M, Rao V, Brister S, et al. Decreasing mortality for coronary artery bypass surgery in octogenarians. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e32–e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hernandez F, Cohn WE, Baribeau YR, et al. In‐hospital outcomes of off‐pump versus on‐pump coronary artery bypass procedures: a multicenter experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1528–1533; discussion 1533–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abraham R, Karamanoukian HL, Jajkowski MR, et al. Does avoidance of cardiopulmonary bypass decrease the incidence of stroke in diabetics undergoing coronary surgery? Heart Surg Forum. 2001;4:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Merry AF. Safer cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2009;41:P43–P47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsui JC, Dashwood MR. Recent strategies to reduce vein graft occlusion: a need to limit the effect of vascular damage. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collaborative meta‐analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meadows TA, Bhatt DL. Clinical aspects of platelet inhibitors and thrombus formation. Circ Res. 2007;100:1261–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangano DT. Aspirin and mortality from coronary bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1309–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pan W, Pintar T, Anton J, et al. Statins are associated with a reduced incidence of perioperative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2004;110(11 suppl 1):II45–II49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dotani MI, Elnicki DM, Jain AC, et al. Effect of preoperative statin therapy and cardiac outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1128–1130, A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klonoff DC. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill hospitalized patients: making it safe and effective. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5:755–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ferguson TB Jr, Dziuban SW Jr, Edwards FH, et al. The STS National Database: current changes and challenges for the new millennium. Committee to Establish a National Database in Cardiothoracic Surgery, The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:680–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]