Abstract

Background

Given the association of depression with poorer cardiac outcomes, an American Heart Association Science Advisory has advocated routinly screening cardiac patients for depression using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) “at a minimum.” Yet, the prognostic value of the PHQ-2 among HF patients is unknown.

Methods and Results

We screened hospitalized HF patients (ejection fraction (EF) <40%) that staff suspected may be depressed with the PHQ-2, and then determined vital status at up to 12-months follow-up. At baseline, PHQ-2 depression-screen positive patients (PHQ-2 (+); N=371) compared to PHQ-2 screen-negative patients (PHQ-2 (−); N=100) were younger (65 vs. 70), and more likely to report NYHA class III/IV than class II symptoms (67% vs. 39%) and lower levels of physical and mental health-related quality of life (all p ≤ 0.002), but were similar on other characteristics (65% male, 26% mean EF). At 12-months, 20% of PHQ-2 (+) vs. 8% of PHQ-2 (−) patients had died (p=0.007) and PHQ-2 status remained associated with both all-cause (hazard ratio (HR): 3.1 (95% CI: 1.4–6.7); p=0.003) and cardiovascular mortality (HR: 2.7 (1.1–6.6); p=0.03) even after adjustment for age, gender, EF, NYHA class, and a variety of other covariates.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized HF patients, a positive PHQ-2 depression screen is associated with an elevated 12-month mortality risk.

Keywords: Depression, heart failure, Patient Health Questionnaire, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a common and growing health problem that affects over 5.7 million Americans with over 660,000 newly diagnosed cases, 277,000 deaths, and $39 billion in direct and indirect costs yearly.1 HF is also the leading cause for hospitalization among Medicare patients, and its five-year mortality rate following first hospitalization exceeds that of all cancers except lung.2 Moreover, heart failure remains the only major cardiovascular disease whose mortality rate has been essentially unchanged over the past decade despite recent advances in its therapeutic management.1

One potential contributor to these persistently poor outcomes is the presence of unrecognized and inadequately treated depression. Depression is highly prevalent among HF patients3, 4 and strong evidence has linked it to increased morbidity and mortality,5–11 higher levels of health services utilization,12 and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) independent of disease severity9, 13, 14 and even at subsyndromal elevations of mood symptoms.8, 9

Several depression screening instruments have been validated for use in cardiac populations and found to have similar psychometric characteristics.15 Given these similarities, a recent American Heart Association (AHA) Science Advisory has advocated a strategy of increased awareness and screening of coronary heart disease (CHD) patients for depression with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)16 “at a minimum”, followed by the nine-item PHQ (PHQ-9)17 to investigate positive screens and provide a severity score that can be used to guide treatment selection and monitoring.18 Unlike other instruments, the PHQ-2 requires nominal training and time to administer and, thus, is feasible for routine use in clinical practice. Still, its prognostic value among patients with HF is unknown. We addressed this question as part of a study to inform later development of a trial to examine the impact of screening and treating depression among patients with HF.

METHODS

Study Setting

We screened HF patients for depression prior to hospital discharge at 4 university-affiliated Pittsburgh-area hospitals, implementing a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh before the start of patient enrollment.

Patient Population

We targeted enrollment of 372 PHQ-2 (+) subjects based on sample size calculations designed to identify the predictive PHQ-917 cut-point score for determining mortality using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses by NYHA class and gender (6 separate analyses), with 80% power, 70–85% sensitivity, 50% minimum specificity, and 90% confidence.19 For comparison purposes, we also planned to enroll a convenience sample of 100 PHQ-2 (−) hospitalized HF patients who met all protocol-eligibility criteria.

From 12/2007 to 4/2009, study nurse-recruiters approached hospital personnel to inquire if they were caring for any patients with heart failure who had a cardiac ejection fraction (EF) of under 40% and suspect might be depressed, and if so to ask for the patient’s verbal agreement permitting the recruiter to approach. If the patient agreed, our nurse-recruiter explained our study to the patient, reviewed our enrollment criteria, and then obtained the patient’s signed informed consent to undergo our screening procedure. We required all patients: (a) have a documented EF <40% as determined by echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, or multiple gated acquisition scan; (b) New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–IV cardiac symptoms; (c) no current alcohol dependence or other substance abuse disorder; (d) score ≥24 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination20 to ensure mental capacity to provide informed consent and reliable responses to our assessment instruments; (e) be medically stable and not have another medical condition known to be fatal within 6 months; (f) be discharged home or to short-term rehabilitation; and (g) be English speaking, have no communication barrier, and have a household telephone. While patients prescribed antidepressant pharmacotherapy at baseline were included in our PHQ-2 depression screen-positive (+) cohort provided they screened positive on the PHQ-2 and met all other eligibility criteria, they were excluded from our PHQ-2 screen-negative (−) cohort.

Baseline Assessment

The PHQ-2 assesses for the presence of the two cardinal symptoms of depression over the past two weeks: “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”.16 We defined a positive PHQ-2 depression screen (PHQ-2 (+)) as patient endorsement of one or both of its items, and a negative screen (PHQ-2 (−)) when the patient responded negatively to both of these items. This classification has 90% sensitivity and 69% specificity for the diagnosis of major depression among CHD patients when measured against the “gold-standard” Diagnostic Interview Schedule.21

Prior to a study subject’s hospital discharge, our nurse-recruiters administered the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)17 to ascertain the severity of mood symptoms; the SF-36 to assess mental (SF-36 MCS) and physical (SF-36 PCS) HRQoL22; the PRIME-MD Anxiety Module to determine the presence of an anxiety disorder23 and conducted a chart review to collect baseline sociodemographic and clinical data. Following the baseline assessment, the recruiters distributed an NIMH brochure entitled “Depression and Heart Disease”24 to all screened patients to heighten their awareness of the impact of mood disorders on heart disease. We also encouraged PHQ-2 screen positive patients via telephone and by mailed letter that they contact their primary care physician (PCP) to discuss this clinical finding, and we sent a similar letter to their PCP also encouraging follow-up.

Vital Status

We ascertained vital status via telephone contact with patients and/or their designated secondary contacts (e.g., spouse, adult child). A study physician classified cause of death (cardiovascular or other) through a review of medical records, obituary notices, and/or written summaries of interviews with secondary contacts and discussions with subjects’ physicians as necessary.

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline sociodemographic, diagnostic, symptom severity, functional status, and current treatment for depression by PHQ-2 status using t-tests for continuous data and chi-squared analyses for categorical data. We used Kaplan-Meier analyses to calculate incidence of all-cause and cardiovascular deaths by PHQ-2 status with log-rank tests to evaluate these differences for statistical significance and Cox models to adjust for differences in baseline covariates. To control for possible confounders of the relationship between mood symptoms and mortality, we adjusted for several recognized predictors of HF mortality.25, 26 They included the presence of anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dl), diabetes, hyponatremia (sodium <136 mEq/L), renal insufficinecy (creatinine >1.7 mg/dL), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) medication, and use of coumadin. As antidepressant medication use could affect mortality risk,27, 28 we repeated our multivariate analyses excluding those PHQ-2 (+) patients using an antidepressants at baseline. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Role of the Funding Source

The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report.

RESULTS

Medical staff at the four study hospitals identified 857 HF patients of whom our nurse recruiters were able to approach and consent 589 (69%) for our screening procedure that was conducted on the median of hospital admission day 4 (mean 5.2 days; range 0–38 days). Of the 520 who completed the PHQ-2, 401 (77%) were PHQ-2 (+) and 371 (93%) then met all protocol-eligibility criteria. However, there was no difference in the rate of PHQ-2 (+) status by quartile of screening day (e.g., 80% PHQ-2 (+) in quartile 1 screened on admission days 0–2 vs. 77% PHQ-2 (+) in quartile 4 screened on admission day 8 or later; p=0.48). Of the 119 PHQ-2 (−) patients, 100 (84%) met all protocol-eligibility criteria making for a total of 471 study subjects (Figure 1). Later, we confirmed vital status at up to 12-months follow-up on all 471 study patients (100%) as of 12/31/09.

Figure 1.

Study recruitment.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

As portrayed in Table 1, PHQ-2 (+) patients compared to PHQ-2 (−) patients were younger (65 vs. 70), and more likely to report NYHA III/IV symptoms (67% vs. 39%), higher levels of mood symptoms (PHQ-9 mean score: 11.3 vs. 3.5), and lower levels of physical (SF-12 PCS: 30.7 vs. 34.3) and mental HRQoL (SF-12 MCS: 44.4 vs. 58.5) (all p ≤ 0.002). While the two groups were similar on other objective sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., 65% male, 85% White, 41% diabetic, 26% mean EF, 82% beta-blocker use), PHQ-2 (+) patients tended to use coumadin anticoagulation therapy at a lower rate than PHQ-2 (−) patients (37% vs. 48%; p=0.06). Moreover, of the 26% (97) of PHQ-2 (+) patients using an antidepressant, 94% were taking either a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (91/97), and just 2% (2/97) were using a tricyclic antidepressant at a guideline-recommended dosage for treating depression.29

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| PHQ-2 (+) (N =371) |

PHQ-2 (−) (N =100) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) range | 65.0 (13.4) 23–91 | 69.6 (11.4) 37–93 | 0.002 |

|

| |||

| Male, % (N) | 64% (237) | 67% (67) | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| Caucasian, % (N) | 85% (315) | 86% (86) | 0.79 |

|

| |||

| Working, part-time or full-time, % (N) | 20% (74) | 21% (21) | 0.82 |

|

| |||

| NYHA Class, % (N) | 0.0001 | ||

| II | 33% (123) | 61% (61) | |

| III | 39% (146) | 32% (32) | |

| IV | 28% (103) | 7% (7) | |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.5 (7.2) | 29.2 (7.5) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 134.2 (68.9) | 145.4 (124.7) | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 78.9 (70.3) | 93.1 (131.2) | 0.30 |

|

| |||

| Ejection fraction (%) (N) | 25.8 (7.8) | 25.3 (7.1) | 0.51 |

|

| |||

| Myocardial Infarction (MI), % (N) | 51% (189) | 58% (58) | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| Post-CABG surgery, % (N) | 42% (158) | 41% (41) | 0.78 |

|

| |||

| Diabetic, % (N) | 42% (156) | 38% (38) | 0.47 |

|

| |||

| Hypertensive, % (N) | 77% (288) | 74% (74) | 0.45 |

|

| |||

| Hyperlipidemia, % (N) | 74% (276) | 71% (71) | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| Atrial fibrillation, % (N) | 41% (152) | 41% (41) | 0.99 |

|

| |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, % (N) | 27% (101) | 25% (25 | 0.66 |

|

| |||

| Renal insufficiency, % (N) | 25% (94) | 24% (24) | 0.78 |

|

| |||

| Sodium, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 138.6 (3.8) | 139.0 (4.0) | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.6 (2.1) | 12.7 (1.9) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| ACE-I or ARB use, % (N) | 74% (275) | 67% (67) | 0.16 |

|

| |||

| Beta-blocker use, % (N) | 83% (307) | 79% (79) | 0.39 |

|

| |||

| Statin use, % (N) | 57% (213) | 66% (66) | 0.12 |

|

| |||

| Spironolactone use, % (N) | 15% (54) | 14% (14) | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Coumadin use, % (N) | 37% (139) | 48% (48) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Aspirin use, % (N) | 76% (282) | 79% (79) | 0.53 |

|

| |||

| Implantable cardiac defibrillator, % (N) | 38% (141) | 29% (29) | 0.10 |

|

| |||

| Biventricular pacemaker/Cardiac resynchronization therapy, % (N) | 19% (72) | 21% (21) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| PHQ-9, mean (SD) | 11.3 (4.5) | 3.5 (2.4) | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| PHQ-9, % (N) | 0.0001 | ||

| 0–4 | 5% (20) | 72% (72) | |

| 5–9 | 32% (119) | 27% (27) | |

| 10–14 | 36% (135) | 1% (1) | |

| 15+ | 26% (97) | 0% (0) | |

|

| |||

| Anxiety disorder, % (N) | 30% (110) | 1% (1) | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Antidepressant use, % (N) * | 26% (97) | -- | |

| SSRI | 20% (75) | ||

| SNRI | 4% (16) | ||

| Bupropion | 2% (6) | ||

| TCA | 1% (2) | -- | |

|

| |||

| SF-12 MCS | 44.4 (11.3) | 58.5 (6.8) | 0.0001 |

|

| |||

| SF-12 PCS | 30.7 (9.2) | 34.3 (10.6) | 0.001 |

Antidepressant use at baseline was an exclusion criterion for inclusion in our PHQ-2 (−) study cohort.

Abbreviations: ACE-I, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker medication; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI, confidence interval; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12 MCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Mental Component Scale; SF-12 PCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Physical Component Scale; SSRI, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Clinical Outcomes

As of 12/31/09, we identified 83 deaths: 75 among PHQ-2 (+) and 8 among PHQ-2 (−) patients, including 55 (66%) for cardiovascular causes.

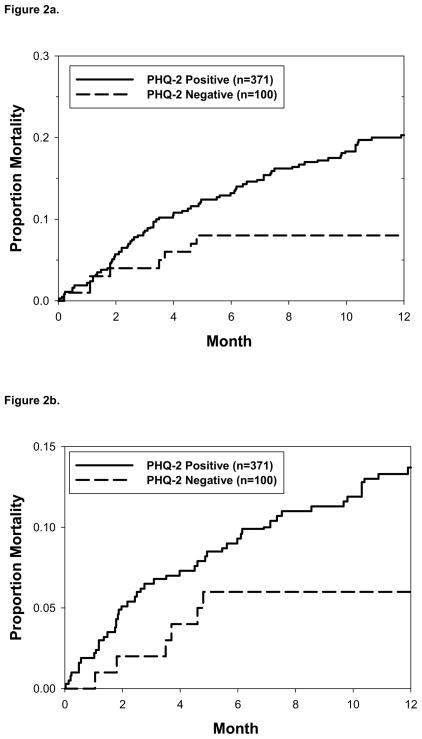

At 12-month follow-up, 20% of PHQ-2 (+) and 8% of PHQ-2 (−) patients had died (p=0.007) (Figure 2a), and an affirmative response to either or both PHQ-2 items conferred a similar risk of mortality (20% for a “yes” answer to “little interest or pleasure doing things”; 19% for “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”; and 20% for “yes” answers to both items). Additionally, a positive PHQ-2 screen was associated with an increased risk of mortality for cardiovascular causes (14% vs. 6%; p=0.05) (Figure 2b) that was also similar by item response (e.g., 13% for a “yes” to “little interest or pleasure doing things”; and 12% for “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. All cause mortality by PHQ-2 status. At 12-months follow-up, 20% of PHQ-2 positive and 8% of PHQ-2 negative patients died (p=0.007).

Figure 2b. Cardiovascular mortality by PHQ-2 status. At 12-months follow-up, 14% of PHQ-2 positive and 6% of PHQ-2 negative patients died (p=0.05).

After adjusting for gender, age, EF, NYHA class, presence of an anxiety disorder, diabetes, renal insufficiency, blood pressure, and a variety of other possible confounders of HF mortality,25, 26 12-month all-cause mortality remained significantly associated with PHQ-2 (+) status (PHQ-2 (+) vs. PHQ-2 (−) hazard ratio (HR): 3.1 (95% CI: 1.4–6.7); p=0.003), age (≥ 65 vs. < 65; HR: 2.1 (1.3–3.4); p=0.004), presence of renal insufficiency (HR: 1.8 (1.1–2.9); p=0.01), use of an ACE-I or ARB (HR: 0.6 (0.4–1.0); p=0.04), and use of a beta-blocker (HR: 0.6 (0.3–0.9); p=0.03) (Table 2). Moreover, PHQ-2 (+) status remained associated with an increased risk of mortality for cardiovascular causes (HR: 2.7 (1.1–6.6); p=0.03). Given the possibly beneficial effects of SSRI antidepressants on cardiovascular outcomes,30 we excluded the 97 patients using an any antidepressant at baseline and found an essentially similar impact of PHQ-2 (+) status on 12-month risk of both all-cause (HR: 3.0 (1.4–6.4); p=0.006) and cardiovascular mortality (HR: 2.5 (1.0–6.2); p=0.05).

Table 2.

Multivariate models of 12-month all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

| All-Cause Mortality | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-2 Status, (+) vs. (−) | 3.1 (1.4–6.7) | 0.003 |

| Gender, female vs. male | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 0.28 |

| Age ≥ 65 vs. <65 | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) | 0.004 |

| Ejection Fraction ≤ 30% vs. >30% | 1.1 (0.6–1.7) | 0.84 |

| NYHA Class, III–IV vs. II | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.12 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.33 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.72 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.8 (1.1–2..9) | 0.01 |

| ACE-I or ARB use | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.04 |

| Beta-blocker use | 0.60 (0.3–0.9) | 0.03 |

| Coumadin use | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.65 |

| Diabetes | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.75 |

| Hemoglobin <10 vs. ≥ 10 g/dL | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 0.26 |

| Sodium, <136 vs. ≥ 136 mmol/L | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.18 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, per 10-unit increase | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.27 |

| Systolic blood pressure, per 10-unit increase | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.27 |

| Cardiovascular Mortality | HR (95% CI) | P |

| PHQ-2 Status, (+) vs. (−) | 2.7 (1.1–6.6) | 0.03 |

| Gender, female vs. male | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 0.21 |

| Age ≥ 65 vs. <65 | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) | 0.13 |

| Ejection Fraction ≤ 30% vs. >30% | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 0.30 |

| NYHA Class, III–IV vs. II | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) | 0.29 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) | 0.70 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 0.69 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.5 (0.9–2.8) | 0.15 |

| ACE-I or ARB use | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.003 |

| Coumadin use | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.97 |

| Beta-blocker use | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 0.17 |

| Hemoglobin <10 vs. ≥ 10 g/dL | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 0.87 |

| Sodium, <136 vs. ≥ 136 mmol/L | 1.4 (0.8–2.8) | 0.27 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, per 10-unit increase | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.08 |

| Systolic blood pressure, per 10-unit increase | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.09 |

Among the 371 PHQ-2 (+) HF patients, the 12-month incidence of all-cause mortality was similar by level of PHQ-9 score (p=0.58; Figure 3). Furthermore, ROC analyses were unable to identify any PHQ-9 cut-point score that significantly predicted an elevated risk of mortality by gender and NYHA class.

Figure 3.

12-Month all-cause mortality by PHQ-9 level among PHQ-2 positive patients (N=371). All-cause mortality by PHQ-9 level was similar by level of PHQ-9 score (p=0.58).

DISCUSSION

Hospitalized HF patients who were suspected by staff of being depressed and then screened positive for depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2 prior to discharge experienced a significantly elevated 12-month risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared to HF patients who screened negative for depressive symptoms. This elevated risk persisted even after adjustment for the severity of heart disease, a variety of other baseline covariates associated with HF mortality, and the presence of a co-morbid anxiety disorder. Furthermore, no follow-up PHQ-9 score level identified any PHQ-2 (+) patients at particularly greater risk of mortality. Our findings are enhanced by our administration of a validated and clinically-efficient depression screening and assessment tool, confirmation of the systolic heart failure using objectively measured criteria, longitudinal study design, complete ascertainment of vital status, and statistical adjustments for a variety of potential confounders.

Despite advances in treatment methods, heart failure remains the only major cardiovascular condition whose mortality has not declined in recent years.1 Given the 40% prevalence of depression among hospitalized HF patients reported by a recent meta-analysis3 and multiple reports that associate depression with a doubled mortality risk,3, 5, 8, 31 our findings have important implications for new approaches to reduce HF mortality. Indeed, the minimal burden placed on providers and patients through administration of the PHQ-2, versus more lengthy depression screening instruments and those that require highly trained personnel to administer, could enable depression screening to become part of routine cardiac care.

Given the elevated prevalence of depression among patients with CHD, its consistent association with adverse clinical outcomes, and underrecognition in this population by clinicians,32–34 the recent AHA Science Advisory has advocated a strategy of increased awareness and screening of CHD patients for depression to identify those who may require further assessment and treatment.18 Yet these recommendations have been controversial as depression screening alone has not been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes.15 Data from randomized trials has recently emerged to support the Science Advisory when screening is coupled with a treatment program35–37; still, none of those studies focused on HF patients.

Also pertinent to clinicians, our findings suggest depressive symptoms may influence patients’ perception of the severity of their HF to a greater extent than its objective severity as measured by their cardiac ejection fraction. Gottlieb et al. reported similar findings after they adjusted for a wide variety of objective measures of exercise capacity and physiology among 2,322 HF patients with NYHA class II–IV symptoms enrolled in the HF-ACTION trial,14 as have other investgators.31, 38 Unrecognized and inadequately treated depression may therefore lead to over-use of health services and increased potential for iatrogenic harm as clinicians attempt to allieviate heart failure “symptoms” through additional tests, “therapeutic” trials and adjustments of pharmacotherapy, and referrals to specialists. Increased awareness of the impact of depression on cardiac symptoms by patients and clinicians and follow-up evaluations for patients who screen positive for depression as recommended by the AHA could potentially improve patients’ perceptions of their cardiac disease, physical functioning, and HRQoL.35–37 However, evidence from well-designed clinical trials is presently lacking to confirm the effectiveness of this strategy among HF patients.39

The generalizability and validity of our study findings is possibly limited as depressed patients are less likely to participate in clinical research than non-depressed patients40 and we did not systematically screen all hospitalized HF patients for mood symptoms. Given the emphasis of our study on enrolling PHQ-2 positive patients, our study nurses requested that hospital staff obtain Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) approval allowing them to approach patients most likely to meet eligibility criteria for study enrollment. Indeed, the 79% of study patients who screened PHQ-2 positive for depressive symptoms is approximately double the prevalence of depression reported by a meta-analysis involving 2,667 hospitalized HF patients (38% prevalence using “liberal cutoffs”)3 and thus may not be representative of other populations of HF patients. Yet we identified similar rates of medical co-morbidity, gender, and employment status at baseline by PHQ-2 status, and adjusted our findings for a varierty of characteristics demostrated to affect HF mortality and PHQ-2 status remained an independent prognostic marker, Furthermore, focusing our screning efforts on patients who had a higher suspicion for depression likely increased the positive predictive value of our PHQ-2 screen. Thus the 0.14 negative likelihood ratio and 4% posterior probability for major depression among PHQ-2 negative patients indicates that a negative PHQ-2 screen can effectively rule-out the presence of major depression.21

Critically, our finding that depression confers a significantly greater mortality risk is consistent with other studies that utilized highly trained personnel to administer complex depression rating scales that are far less practical for use in typical clinical settings.3, 4, 8–11 Indeed, the 8% incidence of all-cause mortality among PHQ-2 (+) patients at 3-months follow-up (Figure 2a) is similar to the 7% mortality rate at 12-weeks experienced by the 469 outpatients with HF and clinical depression that were enrolled in the SADHART-CHF trial (mean Hamilton Rating Scale Score for Depression at baseline: 18.3).39 Additionally, the 20% 12-month mortality rate we observed is similar to the 12-month mortality rate reported by Jiang et al. among 302 hospitalized HF patients who scored 10 or above on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) prior to discharge.8 Finally, the validity of our findings is confirmed by our identification of ACE-I or ARB and beta-blocker use as protective for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in keeping with prior reports,26, 41 and multivariate models that uphold the adverse prognostic risk of a positive PHQ-2 de[ression screen even after adjusting for functional status, cardiac ejection fraction, and a variety of other baseline covariates associated with 12-month mortality risk.

Unlike other studies that used depression rating scales other than the PHQ-9,8, 42–44 we were unable to identify a dose-response relationship between level of mood symptoms and mortality risk. However, we “pre-screened” study patients for depression with the PHQ-2 and this step alone may be sufficient to identify HF patients at highest mortality risk. Still, Jiang et al. were also unable to identify a single BDI cutoff value that best predicted mortality using ROC analyses.8 Nevertheless, given the sensitivity and specificity of a positive PHQ-2 screen for major depression,21 we agree with the AHA Science Advisory recommendation that a positive PHQ-2 screen be so confirmed with the PHQ-9 or a more formal interview18 before active depression treatment be initiated according to evidence-based guidelines45, 46 as a diagnosis of depression cannot be assumed from a postive screen.21

Our findings also highlight the need to better identify the mechanism(s) by which depression may exert its adverse impact on patients with HF. For example, the AHA Science Advisory recommends that patients with cardiac disease be carefully monitored for their adherence with recommended medical care. Yet while we found usage of ACE-Is, beta-blockers, and other medications proven to reduce HF mortality were similar by PHQ-2 status at baseline, we lacked pharmacy claims data to accurately assess medication adherence over the course of follow-up. Additionally, we lacked follow-up data on other factors known to be adversely affected by depression that may also have influenced mortality such as adherence with recommended diet and exercise, tobacco usage, social support, vagal tone, catecholamine and cortisol levels, thrombogenesis, and proinflammatory cytokines.5, 7, 47, 48 Still, we adjusted for the presence of an anxiety disorder that could have amplified mood symptoms, affected patients’ willingness and ability to engage in the self-care needed to manage their HF,49 and confounded the relationship between mood and outcomes we observed.5 Based on reports suggesting antidepressants may affect cardiovascular morbidity,28, 50, 51 we also repeated our models excluding those HF patients on antidepressant pharmacotherapy and obtained essentially the same results, Finally, while we encouraged all patients who screened positive for mood symptoms on the PHQ-2 to discuss further treatment options with their physician, we lacked information on what, if any treatment for depression they may have received over the course of follow-up.

Data from clinical trials still remain necessary to determine whether depression screening and treatment can reduce mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease.52, 53 Nevertheless, safe and effective pharmacologic and counseling modalities for treating depression in patients with cardiovascular disease are presently available15, 30, 36, 37, 46, 54 that may improve HRQoL, physical functioning, and reduce hospital readmissions.35, 37, 45 An increasing number of hospitals and other healthcare delivery organizations already provide care management for HF patients based on the Chronic Care Model,55, 56 and these programs could be adopted to include depression care for greater efficiency. However, just one trial has examined the effectiveness of the Chronic Care Model for treating depression among patients with cardiac disease35 and therefore we know very little about the impact of depression treatment on HF patients.39

In conclusion, our findings confirm the independent and adverse prognostic impact conferred by the presence of even low levels of mood symptoms among hospitalized patients with HF and support the AHA’s Science Advisory’s recommendation to increase awareness and routinely screen all HF patients for depression using the PHQ-2. Although we were unable to identify a follow-up PHQ-9 cut-off score that conferred a particularly elevated mortality risk, we agree with the Science Advisory’s screening algorithm that a positive depression screen be confirmed with the PHQ-9 and more comprehensive clinical evaluation, and treatment provided in accordance with evidence-based guidelines for treating depression.46 Finally, well-designed and well-conducted clinical trials remain critical to establish whether screening HF patients for depression and providing effective treatment can reduce mortality and improve a broad variety of other outcomes of interest to patients, providers, health plans, and purchasors.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented in part at the annual national meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society in Portland OR on March 2010, and at the annual national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in May 2011.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by NIH grant R34 MH078030 (PI: Rollman). None of the other autors have any significant conflicts to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2011 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(00)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferketich AK, Binkley PF. Psychological distress and cardiovascular disease: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1923–1929. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelle AJM, Gidron YY, Szabo BM, Denollet J. Psychological predictors of prognosis in chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor CM, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Clare R, Gattis Stough W, Gheorghiade M, et al. Predictors of mortality after discharge in patients hospitalized with heart failure: an analysis from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Am Heart J. 2008;156:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rathore SS, Wang Y, Druss BG, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM, Rathore SS, et al. Mental disorders, quality of care, and outcomes among older patients hospitalized with heart failure: an analysis of the national heart failure project. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Dec;65:1402–1408. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenig HG. Depression in hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20:29–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J, Russo J. Depression-related costs in heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1860–1866. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turvey CL, Schultz K, Arndt S, Wallace RB, Herzog R. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in a community sample of people suffering from heart failure. JAGS. 2003;50:2003–2008. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb SS, Kop WJ, Ellis SJ, Binkley P, Howlett J, O’Connor C, et al. Relation of depression to severity of illness in heart failure (from Heart Failure And a Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training [HF-ACTION]) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1285–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thombs BD, de Jonge P, Coyne JC, Whooley MA, Frasure-Smith N, Mitchell AJ, et al. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cardiovascular care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300:2161–2171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lesperance F, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou X, Obuchowski N, McClish D Wiley-Interscience. Statistical Methods in Diagnostic Medicine. Chapter 6. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 218–219. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McManus D, Pipkin SS, Whooley MA. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardio. 2005;96:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. 2. Boston: New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of the PRIME-MD. The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depression and Heart Disease. [Accessed November 15, 2011.];NIH Publication No. 02–5004. 2002 Available at: http://www.bypassingtheblues.pitt.edu/h_dhd.html.

- 25.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: Derivation and Validation of a Clinical Model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJV, Swedberg KB, et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer B, Blumenthal JA, de Jonge P, Davidson KW, et al. History of depression and survival after acute myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Med. 2009;71(3):253–259. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819b69e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor CB, Youngblood ME, Catellier D, Veith RC, Carney RM, Burg MM, et al. Effects of antidepressant medication on morbidity and mortality in depressed patients after myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psych. 2005;62:792–798. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Detection and Diagnosis; Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Vol. 1. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. Depression in Primary Care. AHCPR Publication Nos. 93–0550 & 93–0551. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tousoulis D, Antonopoulos AS, Antoniades C, Saldari C, Stefanadi E, Siasos G, et al. Role of depression in heart failure -- Choosing the right antidepressive treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2010;140:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Trivedi R, Johnson KS, O’Connor CM, Adams KF, Jr, et al. Relationship of depression to death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:367–373. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huffman JC, Smith FA, Blais MA, Beiser ME, Januzzi JL, Fricchione GL, et al. Recognition and treatment of depression and anxiety in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J of Cardiology. 2006 Aug 1;98:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konstam V, Moser DK, De Jong MJ. Depression and anxiety in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedland KE, Rich MW, Skala JA, Carney RM, Davila-Roman VG, Jaffe AS. Prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:119–128. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000038938.67401.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Counihan PJ, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, Rubin EH, Lustman PJ, Davila-Roman VG, et al. Treatment of Depression After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:387–396. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson KW, Rieckmann N, Clemow L, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D, Medina V, et al. Enhanced depression care for patients with acute coronary syndrome and persistent depressive symptoms: coronary psychosocial evaluation studies randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:600–608. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, Kutner JS, Peterson PN, Wittstein IS, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;13:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Silva SG, Cuffe MS, Callwood DD, et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) trial. JACC. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nazemi H, Larkin AA, Sullivan MD, Katon W. Methodological issues in the recruitment of primary care patients with depression. Int’l J Psychiatry in Med. 2001;31:277–288. doi: 10.2190/Q8BW-RAA7-F2H3-19BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barefoot JC, Helms MJ, Mark DB, Blumenthal JA, Califf RM, Haney TL, et al. Depression and long-term mortality risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Card. 1996;78:613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, White W, Smith PK, Mark DB, et al. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2003;362:604–609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Screening for depression in adults: U. S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rollman BL, Belnap Herbeck B, Lemenager M, Mazumdar S, Schulberg HC, Reynolds CF., III The Bypassing the Blues Treatment Protocol: Stepped Collaborative Care for Treating Post-CABG Depression. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:217–230. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181970c1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 2008;121(11 Suppl 2):S20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, Otte C, Moos R, Carney RM, et al. Depressive Symptoms, Health Behaviors, and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 2008;300:2379–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, Appel LJ, Dunbar SB, Grady KL, et al. State of the science: promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1141–1163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fosbol EL, Gislason GH, Poulsen HE, Hansen ML, Folke F, Schramm TK, et al. Prognosis in heart failure and the value of {beta}-blockers are altered by the use of antidepressants and depend on the type of antidepressants used. Circ. 2009;2:582–590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.851246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leftheriotis D, Flevari P, Ikonomidis I, Douzenis A, Liapis C, Paraskevaidis I, et al. The role of the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor sertraline in nondepressive patients with chronic ischemic heart failure: a preliminary study. Pacing & Clinical Electrophysiology. 2010;33:1217–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziegelstein RC, Thombs BD, Coyne JC, de Jonge P, Ziegelstein RC, Thombs BD, et al. Routine screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease never mind. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:886–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whooley MA. To screen or not to screen? Depression in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:891–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burg MM, Lesperance F, Rieckmann N, Clemow L, Skotzko C, Davidson KW, et al. Treating persistent depressive symptoms in post-ACS patients: the project COPES phase-I randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gardetto NJ, Carroll KC, Gardetto NJ, Carroll KC. Management strategies to meet the core heart failure measures for acute decompensated heart failure: a nursing perspective. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2007;30:307–320. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000290364.57677.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whellan DJ, Hasselblad V, Peterson E, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA, Whellan DJ, et al. Metaanalysis and review of heart failure disease management randomized controlled clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2005;149:722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]