Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that is considered to be one of the major public health problems worldwide. The development of therapies that target tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and co-stimulatory pathways that regulate the immune system have revolutionized the care of patients with RA. Despite these advances, many patients continue to experience symptomatic and functional impairment. To address this issue, more recent therapies that have been developed are designed to target intracellular signaling pathways involved in immunoregulation. Though this approach has been encouraging, there have been major challenges with respect to off-target organ side effects and systemic toxicities related to the widespread distribution of these signaling pathways in multiple cell types and tissues. These limitations have led to an increasing interest in the development of strategies for the macromolecularization of anti-rheumatic drugs, which could target them to the inflamed joints. This approach enhances the efficacy of the therapeutic agent with respect to synovial inflammation, while markedly reducing non-target organ adverse side effects. In this manuscript, we provide a comprehensive overview of the rational design and optimization of macromolecular prodrugs for treatment of RA. The superior and the sustained efficacy of the prodrug may be partially attributed to their Extravasation through Leaky Vasculature and subsequent Inflammatory cell-mediated Sequestration (ELVIS) in the arthritic joints. This biologic process provides a plausible mechanism, by which macromolecular prodrugs preferentially target arthritic joints and illustrates the potential benefits of applying this therapeutic strategy to the treatment of other inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Macromolecular prodrug, ELVIS, Targeting inflammation, Drug delivery

1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that involves multiple joints in a symmetric pattern. It is characterized by an inflammatory process that targets the synovium, and this process ultimately leads to destruction of the articular cartilage, periarticular bone erosion, and eventual alteration of joint integrity and function. In addition to the joint symptoms, systemic and extra-articular inflammation is also present in many patients. The prevalence of RA in the general population has been estimated to be 0.8% with a 2–3 fold higher incidence in women than in men [1,2]. Although it can occur at any age, it is commonly diagnosed in the middle-aged population (40–60 years of age) [1,3]. In RA patients, the disease-associated disability often occurs early, with approximately 35% of adults reporting premature work cessation within 10 years of their diagnosis [4]. Furthermore, studies have shown that there is a reduced life expectancy in patients with RA compared to the general population. Despite a dramatic increase in the lifespan in the general population, the lifespan of RA patients remains unchanged [5].

There is no cure for RA at present. The most commonly used medications for treatment and management of the disease include: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids (GCs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The modern tools of molecular and cell biology have identified many promising molecules and molecular pathways that can be targeted for immunologic and infiammatory disease intervention. As a result of these efforts, many biological DMARDs have been developed. There is a current emphasis on the early diagnosis and treatment of RA with DMARDs and when combined with other medications, DMARDs have been shown to be effective in controlling the disease progression in many patients [1]. Despite the success of the currently approved DMARDs, significant numbers of patients continue to experience joint inflammation and progressive deterioration in joint structure and function. This has led to an increasing interest in identifying new therapeutic approaches.

More recently, the intracellular signaling pathways that involve a network of intracellular kinases have emerged as particularly attractive targets, as many of the pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators transduce their effects via common converging signal pathways that are regulated by specific families of these protein kinases. Accordingly, therapeutic agents utilizing small molecules suitable for oral delivery have been identified and their clinical efficacy has been provisionally validated in animal models and in human trials [5]. While these newly developed anti-rheumatic drug candidates have specific molecular targets, the management of their in vivo distribution can be very challenging. No intrinsic structural feature specifically targets the drugs to sites of inflammation. The widespread distribution of the drugs has led to a variety of non-target organ and systemic toxicities and there is a need to develop approaches that would reduce these adverse side effects and improve their overall safety profile. It has become evident that the critical barrier that hinders the efficacy and safety of this approach to RA drug development is their lack of in vivo tissue specificity. Several strategies, including liposomal formulations [6–11], have been used to address this challenge. And the results of their evaluation have been extensively reviewed in a recent publication [12]. In general, the liposome formulations have been associated with enhanced targeting and retention at sites of inflammation. The improvement in therapeutic efficacy has been limited to some extent by their requirement for high and frequent dosing that may impose potential risk for systemic side effects. In this manuscript, we will focus on a strategy for drug development based on the design of macromolecular prodrugs to improve the targeting and regulated release of active drug moieties at sites of joint inflammation.

2. The arthrotropism and synovial retention of macromolecules in inflammatory joints

The inflammatory process is characterized by a sequence of defined pathophysiological events. They include alterations in local blood flow associated with the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells of hematopoietic origin, followed by removal of foreign organisms or materials and cell debris, and subsequent stimulation of repair processes that lead to restoration of tissue homeostasis [13]. For inflammatory conditions such as RA, the termination of the inflammatory phase and transition into the tissue repair phase are defective, leading to sustained chronic inflammation. The angiogenesis associated with inflammatory synovial tissue in RA has many similarities to the vascular restructuring found in solid tumors, and the highly vascularized pannus tissue of the RA synovium has been suggested to behave in a tumor-like fashion [14,15].

In solid tumors, the fenestrated vasculature allows macromolecules such as plasma albumin to extravasate preferentially at the tumor sites where they are retained locally due to the presence of a poorly developed lymphatic drainage system. This phenomenon led Maeda H. et al. to propose the so-called “enhanced permeability and retention” (EPR) effect, which has inspired the development of cancer nanomedicine for almost three decades [16]. Whether the inflamed synovium in RA would exhibit similar properties and would therefore be amenable to targeting by macromolecular prodrugs was uncertain. A major concern relates to the presence of apparently preserved lymphatic clearance in inflamed joints [17,18], which would not provide the necessary retention mechanism, but allow a transient increase of drug presence in the articular tissues at the most.

To address this issue, Wang et al. performed a pilot study by intravenously (i.v.) injecting Evan’s blue (EB), a strong albumin-binding dye, in a rat model of adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) [19]. Sustained blue color was observed in the inflamed ankle joints of AA rats 4 h post administration of EB, indicating the extravasation of the plasma albumin into the arthritic synovium, which agreed with the findings using labeled human serum albumin (HSA) [20]. Synthetic macromolecules such as N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymers and linear multifunctional polyethylene glycol (PEG) have also been explored for their potential of arthrotropism in inflammatory arthritis animal models [19,21]. For example, HPMA copolymers were labeled with the MRI contrast agent (DOTA-Gd3 +) and given to AA rats via tail vein injection. Clear arthrotropism of the copolymer was observed within 1 h, with maximum accumulation in the inflamed ankle joints found 8 h post injection. After 48 h, the signal of the HPMA copolymer-based contrast was still clearly evident in the arthritic joints. For healthy animals, however, the polymer was cleared rapidly within 8 h post injection, with no signal found in the ankle joints [19]. These results were further confirmed in studies with IRDye 800CW-labeled linear multifunctional PEG (click PEG), in which the near infrared signal of the polymer was still detectable in the inflamed ankle joints 7 d post systemic administration [21]. These data indicate that natural or synthetic water-soluble macromolecules are indeed arthrotropic in inflammatory arthritis animal models, which may be explained by the extensive angiogenesis and vascular fenestration found in the synovial tissue. On the other hand, the long-term retention of the polymers in the arthritic joints still needs to be explained because of the preservation of lymphatic drainage in the arthritic joints [17,18].

3. The design and development of arthrotropic macromolecular prodrugs for RA

The preliminary imaging studies described above hold the promise for the application of this technology for the development of a more affordable and sensitive tool for detection of joint inflammation and potential early diagnosis of RA. More significantly, the data also suggest that by conjugating anti-rheumatic drugs to the macromolecular carriers, they can be rendered arthrotropic and can be retained locally within joint tissues to provide a sustained and improved therapeutic efficacy while avoiding the potential of non-target organ and systemic toxicity.

To develop a macromolecular prodrug for RA treatment, three critical design factors must be considered. First, the selection and/or design of the macromolecular carriers require a thorough understanding of their biological and physiochemical properties [22]. Validated biocompatibility of the carrier is one of the important selection criteria to ensure the design of a safe macromolecular prodrug. In this regard, the use of a carrier candidate with a proven safety profile is advantageous. The utilization of a new polymeric carrier with unproven biocompatability can impose new risks and necessitate the need for extensive safety validation of both the new carrier and the prodrug from the regulatory point of view. Second, a specific activation mechanism must be considered in the macromolecular prodrug design. A carefully designed cleavable chemical linker between the macromolecular carrier and the drug would ensure its integrity prior to arriving at the inflamed joint and its subsequent controlled cleavage/activation via local pathophysiological factors (e.g. tissue acidosis, local or lysosomal acidity and enzyme activity, etc.). This would result in a regulated local tissue and/or intracellular drug concentration that could be adjusted to achieve optimal local therapeutic efficacy and avoid non-target tissue and cellular toxicities. Third, the rational design of an anti-rheumatic macromolecular prodrug also requires a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism(s) involved in the joint-targeting and retention of the macromolecular prodrugs. As will be discussed in the subsequent sections, the sequestration and uptake of the prodrug by inflammatory and local cell populations plays a major role in their retention at sites of inflammation. Due to the complex immunological responses involved in the inflammatory processes, the phenotype of inflammatory cells associated with the different stages of an inflammatory process can vary significantly, and therefore requires a rational design of the structure and properties of the prodrug according to each individual pathological condition. This is a new area of research that has just emerged in the last decade. The design of several promising prodrugs is discussed in the following sections (see Table 1 for summary).

Table 1.

The macromolecularization of anti-rheumatic drugs.

| Drug | Macromolecular carrier | Linkage between the drug and the carrier | Targeting moiety | Activation mechanism | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs (e.g. naproxen) | Dextran | Ester | None | Esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis | Dextran–naproxen conjugate and naproxen have similar absolute oral bioavailability in pig. Anti-RA efficacy was not tested [26]. |

| Methotrexate (MTX) | Human serum albumin (HSA) | Amide | None | Proteases-catalyzed hydrolysis | When used at a 3.6-fold lower dose, it exhibits a comparable therapeutic efficacy with MTX [20,29]. |

| MTX | HSA | -Maleimide-D-Ala-Phe-Lys-Lys- | None | Proteases-catalyzed hydrolysis | Comparing to the prodrug developed in Ref. [20], this prodrug has well-defined linker chemistry between the drug and the carrier. The anti-RA efficacy is similar [30]. |

| MTX | HPMA copolymer | -Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly-Lys- | Biotin | Proteases-catalyzed hydrolysis | No in vitro or in vivo evaluation [31]. |

| MTX | Dextran | -Pro-Val-Gly-Leu-Ile-Gly- | None | Matrix metalloproteinase II or IX (MMP2/MMP9)-catalyzed hydrolysis | Developed for cancer-targeting therapy. The abundant MMP2/MMP9 in arthritic synovium makes this prodrug a potential drug delivery system in RA therapy [40]. |

| MTX | Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer | Ester | Folate | Esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis | Developed for cancer-targeting therapy, but it also has potential for RA targeting therapy because the overexpression of folate receptor-β on activated macrophages [55]. |

| MTX | PAMAM dendrimer | Ester | MTX itself | Esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis | Developed for cancer-targeting therapy. Comparing to the prodrug developed in ref [55], the chemical structure and synthetic procedure were highly simplified with a comparable cytotoxicity against FR-expressed cells [56]. |

| MTX | PAMAM dendrimer | Amide | RGD peptide | Unclear | Developed for cancer-targeting therapy, but it also has potential for RA therapy by targeting angiogenic endothelial cells [57]. |

| Glucocorticoids (e.g. cortisol) | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Ester | None | Esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis | Very low in vitro hydrolysis rate. Anti-RA efficacy was not tested [63]. |

| Dexamethasone (Dex) | N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer | Hydrazone | None | Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis | Superior and long-lasting (>3 wk) therapeutic efficacy compared to Dex [2,89,95]. |

| Dex | Linear multifunctional polyethylene glycol (click PEG) | Hydrazone | None | Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis | The linear multifunctional PEG carrier was synthesized via click chemistry. The prodrug has long-lasting but relatively weaker therapeutic efficacy when compared to HPMA copolymer based Dex prodrug [21]. |

| Dex | PEG | Hydrazone | None | Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis | Displayed faster in vitro hydrolytic kinetics comparing to the HPMA copolymer [2,89,95] and click PEG [21] based Dex prodrugs which also possess a hydrazone linkage. But in vitro acid-mediated cleavage did not occur at the site of hydrazone bond. No in vivo data available yet [94]. |

3.1. Macromolecular prodrugs of NSAIDs

In the clinical management of RA, NSAIDs are usually used in combination with other therapeutic agents such as glucocorticoids or DMARDs for pain management and symptomatic relief. Most NSAIDs are nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (COX), inhibiting both the cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) isoenzymes. They catalyze the transformation of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, which are critical mediators in the inflammatory process. The inhibition of COX activity, leads to the reduction of pain and inflammation. As a “house-keeping” enzyme, COX-1 regulates many physiological processes, including the protection of the stomach lining from gastric acid erosion. COX-2, on the other hand, is an enzyme highly expressed in inflammatory conditions, and the inhibition of COX-2, therefore represents a rational therapeutic target. This understanding of the differential biological activities of the COX enzymes partially explained the gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleeding and gastric ulcers often associated with long-term use of NSAIDs (nonselective COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors). As a direct result of this knowledge, COX-2 selective inhibitors were developed and found to produce less GI complications [23]. Ironically, some COX-2 inhibitors were later withdrawn from the market due to unexpected cardiovascular safety concerns.

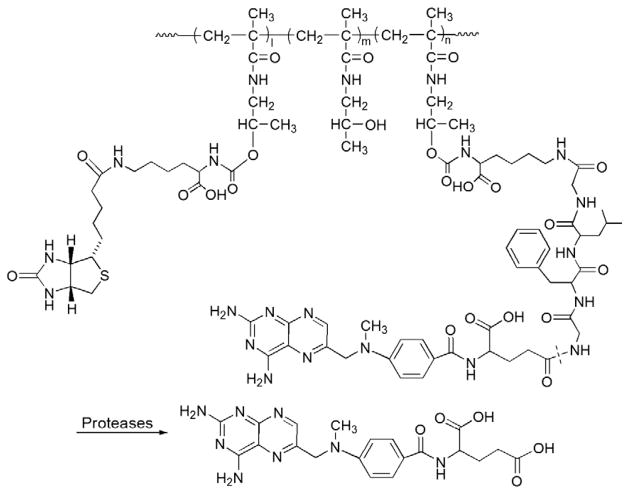

Another pharmacological factor to be considered for the improvement of NSAID therapy is the in vivo management of drug distribution. For oral administration of NSAIDs, only a small fraction of the drug can be absorbed and reach the arthritic joints [24,25]. By conjugation to the macromolecular carrier, one would expect the prodrug to be targeted to the site of inflammation after parenteral administration. Such an approach was first reported in a European patent application, which proposed to conjugate a variety of anti-inflammatory drugs to dextran, a biocompatible polysaccharide generally used as an anti-thrombotic agent [26]. Many NSAIDs contain a carboxylic acid group, which allows direct carbodiimide coupling of the drug to the pendent hydroxyl groups of dextran via an ester bond. One major concern with these ester bonds, however, is their stability in the circulation due to the presence of abundant esterases [27]. In vitro hydrolysis studies of a dextran–naproxen conjugate (Fig. 1) in porcine or leporine liver homogenates, human synovial fluid and plasma supports their stability as it takes more than 100 h to release 50% of naproxen from its dextran conjugates. The stability has been attributed to the steric hindrance of the dextran chain and potential amphiphilicity-driven inter-/intra-molecular micellization of the dextran–drug conjugate, which would limit the esterase accessibility to the ester bond. The inventors also proposed to administer the prodrugs via oral administration. Their intention was to circumvent the adverse GI side effects of NSAIDs by avoiding gastric release but activate the prodrugs in the terminal ileum and colon by glucosidases and hydrolases present at these GI tract segments. In vivo tests in a healthy pig model showed that the absolute oral bioavailability of various dextran derivatives–naproxen conjugates was within the range of 83–106%, which is similar to the oral bioavailability of naproxen itself (90%). No further in vivo animal treatment data are available at the time of this review and no further peer-reviewed publications have been found for this work via a PubMed search.

Fig. 1.

The representative structure and activation of dextran–naproxen prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [26]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

3.2. Macromolecular prodrugs of traditional DMARDs

Over the past few decades, the development of the so-called DMARDs with disease-modifying properties has significantly improved the clinical management of RA, especially at the early stage of the disease. Such therapeutic agents can be further classified into traditional DMARDs comprising a variety of synthetic small molecules, and biological DMARDs produced through genetic engineering. Beyond the function of improving clinical and radiological outcomes, all traditional DMARDs have extra-articular toxicities and thus need regular monitoring for safety concerns. Macromolecular prodrug approaches have been explored to improve the in vivo PK/BD profile of these agents, particularly methotrexate (MTX), and thus to potentiate its efficacy as well as to reduce its off-target toxicities. MTX was originally developed for cancer therapy, but was later shown to be a slow acting but effective DMARD in RA management. It was established as the first line treatment for RA in the early 1980s. The antirheumatic mechanism of MTX is thought to be partially ascribed to its up-regulation of the expression of extracellular adenosine, a potent anti-inflammatory molecule [28]. Most of the macromolecular prodrugs of MTX were developed initially for cancer therapy. Only albumin-based MTX prodrugs have been evaluated for therapeutic efficacy in inflammatory arthritis animal models [20,29,30]. In addition to this conjugate, a biotin-containing HPMA copolymer–MTX prodrug (MTX–PHPMA–biotin), which was designed for macrophage- and dendritc cell-targeting delivery of MTX, was developed. However, minimal data are available from in vitro or in vivo efficacy studies [31]. This section will also discuss additional MTX-macromolecular prodrugs that have been developed for tumor therapy and their potential use in inflammatory conditions.

3.2.1. Macromolecular MTX prodrugs developed for RA therapy

Albumin (MW~67 kDa) is the dominant plasma protein in human serum (35–50 g/L). It resists denaturation by various chemical reagents and by heat (at 60 °C for up to 10 h), and is stable in the pH range of 4–9 [32]. Furthermore, its tropism to tumors and inflammatory tissues, as well as its biological properties, including long circulating half-life (~19 days), lack of toxicity, nonimmunogenic and lysosomal biodegradable properties make it a very promising candidate as a macromolecular prodrug carrier. Initially, It was exploited as a carrier for tumor-targeting delivery of MTX [33,34], and very promising results were obtained with MTX–human serum albumin (HSA) conjugates in phase I cancer clinical trials [34]. Currently, it is being evaluated in phase II clinical trials [35]. Because of the successful oncological application of MTX–HSA conjugates, its use in improving the treatment of RA was proposed. In addition to the enhanced extravasation of albumin into arthritic joints, there is evidence of its enhanced metabolism in cells such as RA synovial fibroblasts [36,37], making it a potential carrier system for targeting delivery of a drug into inflamed joints.

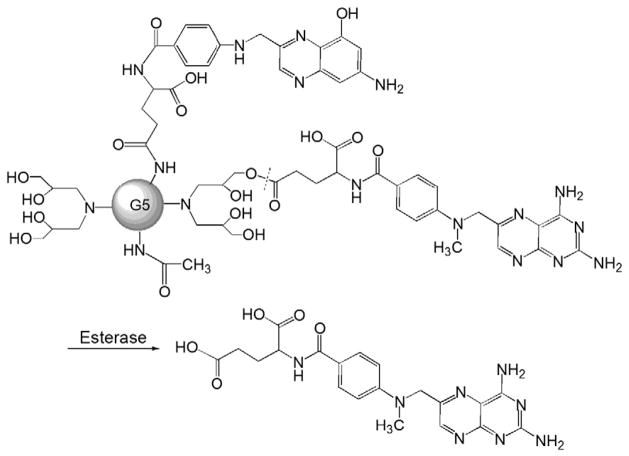

The design of an MTX–HSA prodrug is straightforward [33]. The synthesis utilized the primary amine groups of HSA and the two carboxylic acids of MTX for conjugation. Briefly, the carboxyl groups of MTX were first activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) to form activated esters via N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) coupling. The albumin-MTX with a different MTX loading ratio (MTX/albumin=1:1, 5:1, 7:1, 10:1 and 20:1; mol/mol) could then be prepared by addition of different amounts of NHS-activated MTX into the PBS solution (pH 7.4) of albumin. The linkage between HSA and MTX is a stable amide bond, which is not easily cleaved in the circulation. An in vivo pharmacokinetics and biodistribution (PK/BD) study showed that the circulating half-lives of these conjugates declined when the MTX loading ratio was increased. The conjugate with a molar loading ratio of 1:1 exhibited the lowest RES (reticuloendothelial system) uptake with a biodistribution pattern comparable to albumin [29,32,33]. This conjugation strategy is also straightforward for protein modification. The limitation of the technique, however, is that there is no method to target the primary amine in HSA and select the two carboxylic acids of MTX. One may also anticipate the possible formation of an HSA dimer through MTX-mediated cross-linking. Due to the complexity of the conjugation chemistry, the structure of MTX–HSA could not be clearly defined. This has resulted in batch-to-batch variance of the prodrug in terms of the MTX releasing rate and mechanism. In order to overcome this limitation, Fiehn et al. introduced an enzymatically cleavable peptide linker bearing a maleimide group (maleimido-D-alanylphenyllysyllysine, maleimido-D-Ala-Phe-Lys-Lys). The lysine residue was coupled to MTX via an amide bond, and the maleimide group could be selectively conjugated to the cysteine-34 position of HSA via a thioether bond (Fig. 2). The linker can be cleaved by two proteases (i.e. cathepsin B and plasmin) that are over expressed in inflamed synovium. The activated MTX lysine derivatives exhibit similar biological effects as MTX [30].

Fig. 2.

The chemical structure and activation of HSA-maleimido-D-Ala-Phe-Lys-Lys-MTX prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [30]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

In a PCT patent application published in 2004, the structural designs of a series of prodrugs with active targeting moieties were revealed, among which a biotin-containing HPMA copolymer–MTX conjugate was found to have potential application in the treatment of RA [31]. Biotin, a water-soluble B-complex vitamin (VB7), plays an important role in cell growth, fatty acid production, as well as metabolism of fat, protein and carbohydrate. It has been widely used in the laboratory as a tracer and in imaging studies with IgG monoclonal antibodies. Due to its extremely high affinity for avidin and streptavidin, biotin/avidin and biotin/streptavidin systems have been used in a variety of fields, including bioanalysis, drug delivery and targeting, and in vivo imaging. For drug delivery, biotin has been identified as a targeting moiety for a variety of tumor cells, macrophages and dendritic cells where the “cargo” can be internalized via biotin-receptor mediated endocytosis [31,38,39]. MTX–PHPMA–biotin was disclosed with the following structural design. The carboxyl group from biotin and MTX was linked to Lys or a Lys-containing peptide linker (GlyPhe-Leu-Gly-Lys) via an amide bond. After the hydroxyl group from the HPMA homopolymer was converted to an active ester by a linker of disuccinimidyl carbonate, biotin-Lys or MTX-Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly-Lys was conjugated to the polymer via a carbamate bond (Fig. 3). The design criteria for this macromolecular prodrug are: 1) The size of the polymer carrier should be below the renal excretion limit to reduce the risk of its accumulation within the body following continuous treatment as PHPMA is nonbiodegradable; 2) The selected peptide linker (Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly-) for MTX conjugation is cleavable by lysosomal enzymes following biotin-mediated cellular uptake by macrophages or dendritic cells. No follow-up in vitro or in vivo evaluation has been reported, and it is not known if the introduction of biotin would further potentiate the prodrug’s targeting efficiency.

Fig. 3.

The chemical structure and activation of biotin-containing HPMA copolymer–MTX prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [31]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

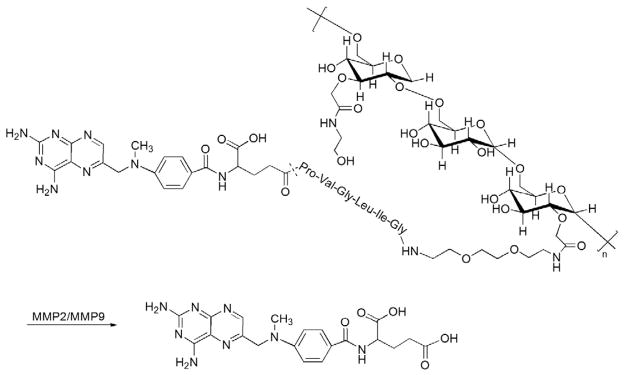

3.2.2. Macromolecular MTX prodrugs with potential for RA therapy

A novel tumor-targeting dextran–peptide–MTX conjugate was developed using an oligopeptide linker (Pro-Val-Gly-Leu-Ile-Gly) which is sensitive to matrix metalloproteinase II (MMP-2) and matrix metalloproteinase IX (MMP-9) [40]. Both enzymes were found to be overexpressed by tumor cells in various human epithelial cancers (i.e. breast, prostate, colon, ovary, bladder and gastric carcinoma) [41–46]. Importantly, a variety of MMPs (i.e. MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-13) are also overexpressed in RA synovium in response to proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β and TNF-α), and these enzymes contribute to the destruction of cartilage, bone and tendons in the joints [47]. Based on these observations, one would predict that a macromolecular prodrug incorporating an MMP-sensitive linker would also be applicable for treatment of inflammatory arthritis. Because of its biocompatibility and biodegradability, dextran (MW of 70 kDa) with a size above the renal excretion limit was selected to achieve a better passive targeting efficiency. In order to be linked to the terminal amine group of the MTX–peptide conjugate, dextran was modified with a carboxymethyl (CM) group at a substitution degree of 50%. In this particular design, the γ-carboxyl group of MTX was chosen as the conjugation site, while the α-carboxyl group, which is the less tolerable functional group, was protected to form a tert-butyl ester throughout the synthesis process (Fig. 4). Then the protected MTX was conjugated to the peptide which was immobilized on O-bis(aminoethyl) ethylene glycol trityl resin. With this resin, the peptide can be attached with jeffamine, which can increase the hydrophilicity of the relatively hydrophobic peptide-MTX, and thus to enhance its conjugation yield with the highly hydrophilic CM-dextran backbone using an EDC coupling procedure. In an investigation of the influence of the dextran backbone charge on the kinetics of enzymatic hydrolysis of the conjugates by MMP-2 and MMP-9, the least negatively charged conjugates possessed the highest sensitivity toward both enzymes. Therefore, after conjugating CM-dextran with jeffamine–peptide–MTX, the author neutralized the excess CM groups with ethanolamine. Since this macromolecular pro-drug is designed for systemic administration, it is very important to maintain its integrity before it reaches the targeting site. The author performed in vitro stability studies in both fetal bovine serum (FBS) and FBS spiked with high levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9. The latter experimental condition closely approximates the pathological conditions of the cancer/RA patients, where the tumor tissue or arthritic joints overexpress MMP-2 and MMP-9 [48]. However, the enzymatic activities of the MMPs are markedly inhibited by serum proteins (e.g. α2-macroglobulin). The results showed that this dextran–peptide–MTX conjugate had no significant cleavage either in FBS alone or in FBS spiked with MMP-2 and MMP-9. By contrast, the conjugate displayed a 14% cleavage after 6 h incubation with a human fibrosacroma cell line (HT-1080) which is known to express MMP-2 and MMP-9, indicating that this peptide linker is specific to only the active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Although the primary intention of this design was not for targeting delivery of MTX to the arthritic joints, the arthrotropism of this prodrug in RA subjects is predictable due to its large MW. More importantly, the arthritis-associated increase of MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in synoviocytes makes this specific enzyme-labile design a favorable approach for development of novel anti-RA macromolecular prodrugs. Further investigation of the in vivo PK/BD profile of this prodrug in RA animal models is thus warranted.

Fig. 4.

The chemical structure and activation of dextran–MMP2/MMP9 cleavable peptide–MTX prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [40]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

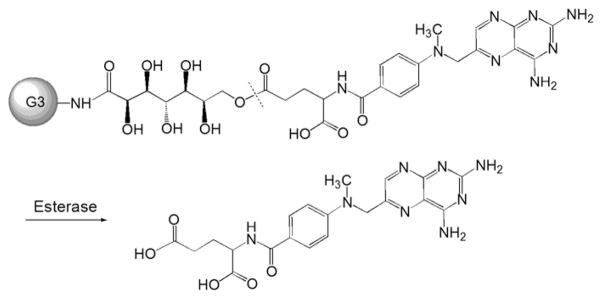

Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers are a group of highly branched and narrowly dispersed (PDI≈1) synthetic polymers with a well-defined structure which allows precise control of shape, size and terminal group functionality [49]. They have been extensively investigated for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, particularly as nanocarriers for drugs, genes and imaging agents [50–54]. Although it has been reported that amine-terminated PAMAM dendrimers possess cytotoxicity, chemically masking the excess amine groups can avoid this problem. Recently, a series of novel poly-amidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer-based MTX conjugates with or without attachment of a tumor-targeting moiety {i.e. folate and Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide} were developed by the Baker laboratory [55–57]. While folate was extensively utilized in tumor-targeting drug delivery systems, a functionally active folate receptor (FR)-β form is highly expressed by activated but not resting synovial macrophages from RA patients, suggesting that folate could also be employed for targeting delivery of drugs or diagnostic agent to arthritic joints [58].

A series of FR-targeted PAMAM dendrimer–MTX conjugates have been synthesized, and the generation 5 (G5) PAMAM dendrimer was initially used [55]. At the initiation of the synthesis, the surface primary amine groups were neutralized through partial acetylation to prevent their nonspecific intermolecular interactions that often causes cytotoxicity. Folates were then attached to the primary amine group of the dendrimer via the EDC coupling procedure (Fig. 5). The remaining primary amine groups were reacted with glycidol to yield hydroxyl functional groups, which were used for MTX conjugation via an ester bond in the next step. Instead of directly attaching the MTX molecule to the primary amine groups of the dendrimer via an amide bond, which might be too stable to be cleaved in vivo, the authors chose an ester linkage, which is usually more cleavable due to the presence of esterase. In the structure of both MTX and folate, γ-carboxyl is much more reactive than the α-carboxyl group during EDC-mediated coupling reaction. However, α-carboxyl group is still able to participate in the reaction, leading to a mixture of four components with various ratios in the final product. Furthermore, MTX conjugated at different sites will have different release rates, which can directly affect the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of the prodrug. Finally, high generation dendrimers are normally difficult to be produced especially during scale-up synthesis due to side reactions and formation of defective structures in a multistep chemical reaction, which could be further exacerbated by the covalent attachment of bioactive agents. This would be one of the major challenges for the clinical translation of this technology in the future. In order to prepare a more reproducible dendritic FR-targeting MTX prodrug, Zhang et al. used a lower generation PAMAM dendrimer (G3 PAMAM) to reduce the synthetic steps [56]. Moreover, because of the anti-folate properties of MTX, the author proposed to use MTX itself as a ligand to achieve FR-targeting intracellular delivery instead of folate, which would further simplify the synthetic route and the chemical structure of the prodrug. Nevertheless, low generation dendrimers coupling with lipophilic drugs often yield poorly water-soluble conjugates. To enhance the water solubility of the final prodrug product, the author modified the amino termini of G3 PAMAM with a saccharide lactone (D-glucoheptono-1,4-lactone). The additional advantage of this modification is that the multiple hydroxyl groups from the saccharide would allow for conjugation with the MTX molecule (Fig. 6). The in vitro study demonstrated that this prodrug was internalized by the FR-expressing cells via multivalent FR binding, and exhibited cytotoxicity comparable to the G5 PAMAM–folate–MTX conjugate.

Fig. 5.

The chemical structure and activation of G5 PAMAM–folate–MTX prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [55]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

Fig. 6.

The chemical structure and activation of G3 PAMAM–MTX prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [56]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

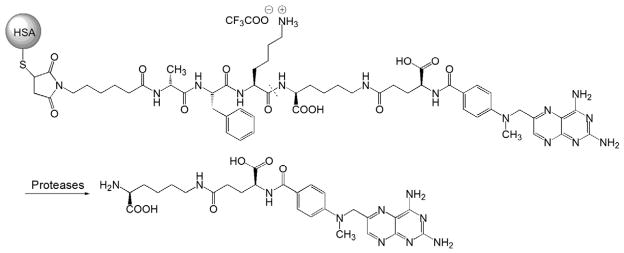

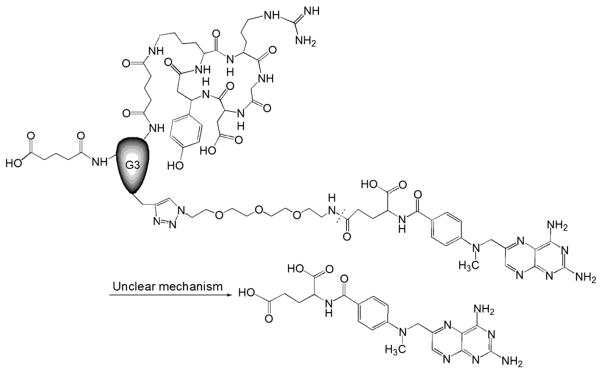

RGD peptides can specifically bind to the αvβ3 integrin on the angiogenic vascular endothelial cells (VECs), making this integrin a promising target in inflammatory diseases such as RA [59]. Macromolecular prodrugs containing RGD sequences are therefore promising candidates to potentiate the efficacy of MTX in RA treatment. In the particular design of an MTX–G3 PAMAM dendrimer–RGD conjugate (MTX–G3 PAMAM–RGD), Cu(I)-catalyzed 1, 3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction was employed for MTX conjugation at the focal point of the G3-PAMAM dendrimer, while multiple RGD peptides were attached to the surface of the dendrimer via carbodiimide chemistry [57]. Firstly, the alkyne-functionalized G3-PAMAM dendrimer was synthesized using propargylamine as a focal point. Then the surface amine groups were modified with glutaric anhydride to form carboxylate functional groups to which RGD was conjugated via EDC coupling. MTX was reacted with 11-azido-3,6,9-trioxaundecan-1-amine to yield an azide-functionalized drug molecule which was finally attached to the PAMAM dendrimer at the alkyne-functionalized focal point via click chemistry (Fig. 7). In vitro cytotoxicity studies showed that this prodrug and free MTX exhibited comparable cytotoxicity, suggesting that this binary dendrimer platform may serve as an effective targeting delivery system for either therapeutic applications or as an imaging agent to target angiogenic endothelium. The major advantage of this design is that the employment of click chemistry at the focal point of the dendrimer allows MTX to be attached in a precise manner, and the dendrimer with multiple RGDs on the surface is able to potentiate its binding avidity through multivalent cell interactions. Regarding in vivo application of this macromolecular prodrug, however, one concern would be that the amide bond between the MTX molecule and dendrimer is relatively stable and may not be efficiently cleaved at the targeting site. The other concerns include in vivo toxicity associated with the copper catalyst residue and the low drug-loading rate (only one MTX molecule per dendrimer).

Fig. 7.

The chemical structure and activation of MTX–G3 PAMAM–RGD prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [57]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

3.3. Macromolecular prodrugs of glucocorticoids (GCs)

GCs are the most potent anti-inflammatory drugs and exhibit rapid therapeutic action. Clinically, they are used to suppress allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune disorders, including RA. As a general therapeutic management strategy, GCs are often used in the early phases of RA treatment to quickly relieve symptoms. Disease modifying activity has also been demonstrated in clinical trials [60]. However, long-term use of GCs is associated with severe side effects, including skin atrophy, osteoprosis, muscle atrophy, cataracts, glaucoma, peptic ulcer disease and increased risk of infection. Based on the generalized actions of GCs, selective GC receptor agonists have been developed that selectively target the immune and inflammatory pathways in order to reduce the systemic toxicity of GCs [61,62]. From a pharmacological perspective, alteration of GCs’ in vivo distribution would serve as another viable strategy to overcome their off-target toxicities. As discussed in the following subsections, the currently developed GC macromolecular prodrugs can be categorized into enzymatic and acidic-cleavable designs based on their linkage types. The prodrugs, which were specifically developed for RA therapy, are discussed in more detail.

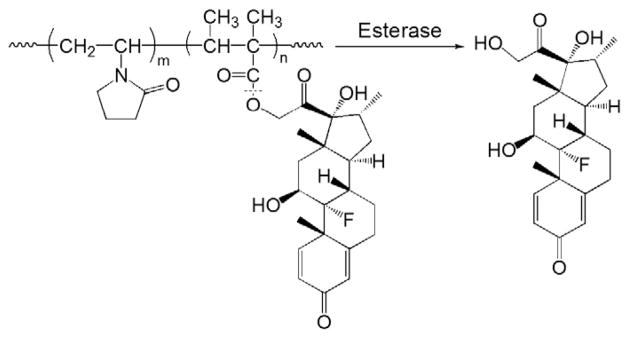

3.3.1. Enzymatic-cleavable macromolecular GC prodrugs

In the chemical structure of GC, the C21-hydroxyl group is the most obvious and convenient modification site. Hence, a large number of GC macromolecular prodrugs were developed by covalently conjugating GC molecules to polymeric carriers via an ester linker [63–70]. As an example of such an approach, Timofeevski et al. developed a water-soluble polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) based polyester of dexamethasone (Dex, a potent GC) [63]. PVP was selected as the macromolecular carrier because of its well-recognized biocompatibility [71]. As the first step of drug conjugation, Dex-containing co-monomers were synthesized by coupling the primary hydroxyl group of the Dex molecule with crotonic acid via an ester bond. The polyester was then synthesized via free radical copolymerization of N-vinylpyrrolidone with Dex-containing co-monomers (Fig. 8). In this prodrug design, one common concern about the ester bond is its potential poor in vivo stability during circulation. Though these polyester analogs of Dex were found to be very stable against hydrolysis in buffers (pH 5.2–7.3) with only 1–5% of Dex released per year, it is anticipated that it would be quickly activated in the circulation after administration because of the presence of abundant circulating esterases. The prodrug was found to be more effective in a de-clamping shock model than equivalent doses of free Dex, which may be explained by its longer half-life in the circulation and rapid in vivo activation. It was also found to produce less systemic immunosuppression than free Dex.

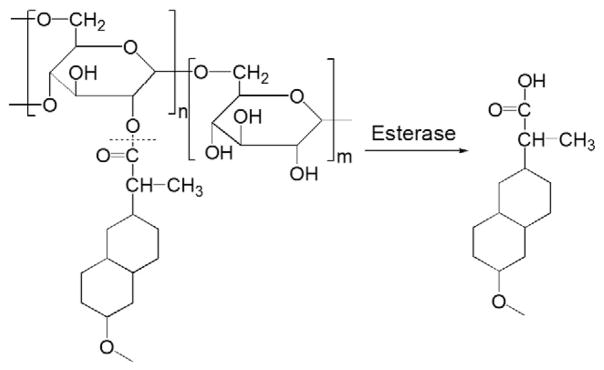

Fig. 8.

The chemical structure and activation of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)–dexamethasone prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [63]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

Over the past decade, similar strategy has also been utilized in the development of a variety of GC macromolecular prodrugs for therapy of different inflammatory diseases or tissue injury models [64–70]. Despite the diversity of polymers {i.e. dextran, chitosan, dendrimers, and poly(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (PDMAEMA)} and the model drugs (i.e. methylprednisolone, prednisolone and budesonide) used, the general design principle of these prodrugs is very similar. Generally, C21-ester derivatives of GC were firstly constructed using a bifunctional linker which was able to react with the functional group of the polymer carriers. Nevertheless, in vitro release studies with these prodrugs showed that they mostly displayed very rapid hydrolytic kinetics with nearly 40% of the drug being released within 12–48 h in PBS (pH 7.4), suggesting an even faster in vivo cleavage during circulation due to the ubiquitous presence of esterases. Therefore, such designs would not meet the needs of the sustained prodrug activation kinetics for treatment of a chronic inflammatory condition such as RA.

3.3.2. Acidic-cleavable macromolecular GC prodrugs

The HPMA copolymer was chosen as the macromolecular carrier of the prodrug because it has been designed and extensively studied as a water-soluble, biocompatible drug carrier for many years [72–75]. The homopolymer of HPMA was first introduced as a blood plasma expander, and its biocompatibility was extensively investigated [76]. The biocompatibility of HPMA copolymers containing attached haptens {arsanilic acid (ARS), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)} as drug models [77] and oligopeptide side-chains [78] was also evaluated. It was shown that the homopolymer was not recognized as a foreign macromolecule in any of the five inbred strains of mice studied, and there was no evidence of the development of antibodies [78]. Attachment of oligopeptide side-chains gave rise to compounds possessing very weak immunogenic activity. The intensity of the response depended on the structure of the side-chain, dose, and genetic background of the mice. Gly-Gly side chains were the least immunogenic. Neither the homopolymer nor the copolymers of HPMA possessed mitogenic activity. The intensity of the immunogenic response increased with increasing molecular weight of the conjugate. While the ARS–HPMA copolymer conjugate behaved as a high dose tolerogen, tolerogenicity was not observed with the FITC conjugate. Generally, HPMA copolymers behaved as thymus-independent antigens with low immunogenicity [79–81]. The immune response towards HPMA copolymers was about 4 orders of magnitude lower than human gamma globulin [82].

Recognition of the characteristics of the RA joint and synovial pathology suggests that an acid cleavable linker might be an optimal choice for design of a prodrug. Acidosis of synovial fluid (SF) is a characteristic feature of inflamed joints, where the pH value of SF has been shown to be as low as 6.0, and in some cases even lower than 5.0 [83–86]. The acidic environment has been attributed to an imbalance between increased metabolic activity and insufficient oxygen supply, which induces a shift toward anaerobic glycolysis and lactate formation [87,88]. By linking the drug and the macromolecular carrier with an acid-cleavable bond (e.g. hydrazone bond, cis-aconityl bond, Schiff base or acetal bond), this unique pathophysiological feature can be exploited as a disease-specific drug activation mechanism, which would further define its inflammatory joint specificity. Moreover, the intracellular lysosomal compartment (pH 5.5–6) might be another activation trigger for prodrugs with acid-sensitive linkage because most of the polymeric drug conjugates are trafficked into a lysosomal compartment after their endocytosis by activated synoviocytes.

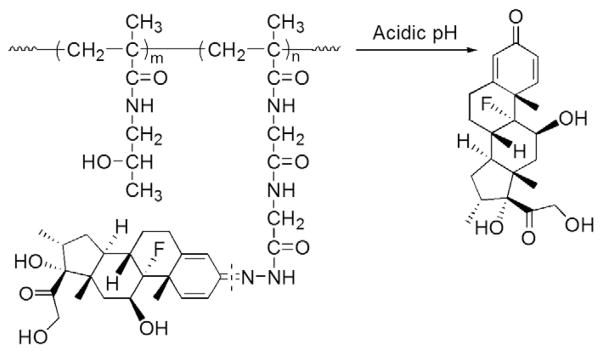

In the first of a series of published papers on this prodrug development strategy, Wang et al. reported the results of a study using a HPMA copolymer-based Dex prodrug [89]. The two carbonyl groups of Dex were designed as potential conjugation sites by linking them to the HPMA copolymer via a hydrazone bond. In the original synthetic design, the copolymer of HPMA and methacryl glycylglycine (P-Gly-Gly-OH) was initially synthesized via free radical polymerization. After modifying the carboxyl group of the side chain (Gly-Gly-OH) into a hydrazide structure, a polymer analog reaction was used to conjugate Dex to the copolymer via a hydrazone bond. Despite the simplicity of this synthetic route, a challenging issue is the batch-to-batch variation in Dex content of the generated polymeric conjugate. To address this limitation, Liu et al. synthesized an acid-cleavable Dex-containing monomer (MA-Gly-Gly-NHN=Dex) which was copolymerized with the HPMA monomer using reversible addition-fragmentation transfer (RAFT) polymerization to produce the macromolecular Dex prodrug (P-Dex, Fig. 9) [2]. In addition to the precise control of the Dex content in the prodrug, the other advantages of this improved synthetic route include: 1) no unreacted pendent functionalities; and 2) better control of MW and polydispersity (PDI=1.2–1.3). An in vitro study found that P-Dex was indeed cleavable under acidic conditions (pH=5.0) at a rate of 1% of the total Dex loaded per day during the entire testing period (14 days). No significant Dex release was found in PBS (pH 6.0 and 7.4) or in rodent plasma [2,90].

Fig. 9.

The chemical structure and activation of HPMA copolymer–dexamethasone pro-drug (Adapted from Ref. [2]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

In addition to the linker chemistry, the impact of the structural parameters (e.g. molecular weight, drug loading, etc.) on the macromolecular prodrugs’ PK/BD profiles has also been investigated by Quan et al. using the AA rat model [90]. It was found that the increase of both the MW (from 14 to 40 kDa) and Dex content (from 0 to 313 μmol/g) facilitated the distribution of P-Dex to the arthritic joints potentially due to its prolonged circulation half-life. Moreover, adjustment of the structural parameters enhanced the splenic uptake of the prodrug, which likely contributed to the amelioration of the spleen enlargement (splenomegaly) found in the AA rats.

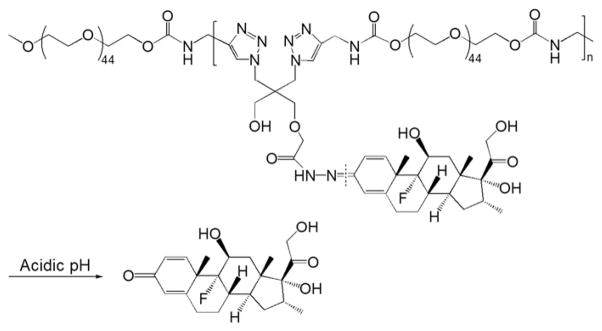

In macromolecular prodrug design, the chemical structures of the biocompatible polymeric carriers are associated with different biological properties [91]. To explore this possibility, Liu et al. reported a new acid-cleavable macromolecular prodrug of Dex based on PEG [21]. As a biocompatible water-soluble polymer, PEG has been widely used in conjugation with protein and low MW drugs [92,93]. A few PEG–low MW drug conjugates have progressed into clinical trials (e.g. Pegamotecan, a camptothecin–PEG conjugate) [92]. However, a major limitation of this strategy is that PEG only has two chain termini for chemical modification or conjugation regardless of their MW, resulting in their low drug loading capacity. To overcome this limitation, the authors developed a linear multifunctional PEG conjugate using Cu(I)-catalyzed Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (a click reaction) [21]. In this design, an acid-cleavable Dex monomer was synthesized by coupling Dex to a hydrazide-containing diazide compound through a hydrazone bond. The monomer was then click-copolymerized with short acetylene-terminated PEG chains in the presence of tris-(hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl)amine (THPTA; stabilizing agent), Cu(I) catalyst and acetylene-modified mPEG (chain terminator to control the MW), which produce a linear multifunctional PEG–dexamethasone conjugate (click PEG–Dex). The copolymerization is modular, simple and highly efficient. For the removal of the copper catalyst residue, the authors utilized a combined LH-20 column fractionation and EDTA disodium salt-assisted dialysis strategy, which successfully eliminated over 99.5% of the added Cu catalyst. Compared to the prodrugs synthesized via free radical copolymerization, click PEG–Dex (Fig. 10) has a perfectly defined molecular structure with each drug unit evenly distributed along the linear multifunctional PEG chain. Due to the polycondensation nature of the click copolymerization, however, click PEG–Dex has a large polydispersity index (PDI ~3). Fractionation is therefore necessary to control MW, reduce the PDI value and allow potential translation of the prodrug into clinical application. Interestingly, when tested for in vitro Dex release, click PEG–Dex showed a slower releasing profile comparing to P-Dex. Though the same hydrazone linker was used in both prodrug designs, this result may be related to the potential impact of different local micro-environmental factors (HPMA copolymer or PEG) on the hydrazone cleavage process.

Fig. 10.

The chemical structure and activation of click PEG–dexamethasone prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [21]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

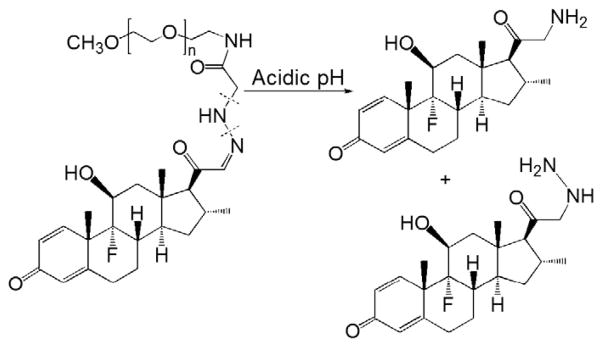

More recently, Funk et al. developed a novel acid-cleavable PEG–Dex derivative conjugate (PEG–DexHAc) [94]. Before conjugation to the polymer, an α-keto aldehyde derivative of Dex was prepared by heating Dex, and then reacted it with hydrazino acetic acid to form a hydrazone bond-bearing derivative, Dex hydrazino acetic acid (DexHAc). The carboxyl group from this derivative was able to be coupled with amino-terminated PEG via an amide bond (Fig. 11). An in vitro hydrolysis study was performed under acidic conditions (pH 5.0), and this macromolecular produg showed an accelerated hydrolytic rate (63% after 14 days) when compared to the HPMA copolymer and click PEG–Dex conjugates. More interestingly, two unexpected derivatives (Fig. 11) rather than the α-keto aldehyde derivative were found in their further analysis of the degradation products, indicating that cleavage did not occur directly at the site of the hydrazone bond. The biological activity of Dex is mostly related to the C3-carbonyl, C16-methyl, C20-carbonyl, fluoro atom as well as the ring structure (A–D). Because of the maintenance of all of these structural features in the two degradation products, their biological efficacy should be maintained. In a cell culture study, it was found that this conjugate had GC receptor-mediated biological activities. These activities could be blocked in the presence of a lysosomal inhibitor, suggesting that the lysosomal acid-activation is necessary for the prodrug to exert its biological effects. On the other hand, because of the more complex physiological environment in vivo, it would be very interesting to investigate the composition of the degradation products as well as their biological efficacy in ex vivo tissue/cell culture models and in vivo experimental conditions.

Fig. 11.

The chemical structure and activation of PEG–dexamethasone prodrug (Adapted from Ref. [94]). Dotted line indicates cleavage site.

4.In vivo therapeutic efficacy of macromolecular prodrugs

4.1. Albumin–methotrexate conjugates (MTX–HSA)

In a preclinical prophylactic study, MTX–HSA and MTX were both given twice weekly to mice with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), and their impact on the incidence of inflammatory arthritis was evaluated [20]. The treatment was initiated 2 weeks before the onset of the disease and the treatment lasted for 4 weeks. Low-dose MTX treatment (7.5 mg/kg) failed to prevent the onset of RA (57% arthritis incidence with no significant difference from the untreated group), whereas MTX–HSA (containing an equivalent MTX dose) significantly reduced the arthritis incidence to 28%. To obtain a comparable therapeutic effect to the MTX–HSA group (7.5 mg/kg of MTX), a 4–5-fold higher dose of free MTX (35 mg/kg) was required. Clinically, unconjugated MTX is given weekly to RA patients orally or subcutaneously. Its half-life in the circulation is 6–8 h. The phase I clinical trial data showed that the plasma half-life of MTX–HSA is around 15 days in cancer patients, which is similar to HSA alone. Clearly, coupling the MTX to albumin enhanced its systemic drug exposure and may facilitate the macromolecular prodrug’s arthrotropism when joint inflammation is present.

4.2. Acidic-cleavable HPMA copolymer–Dex conjugates

The in vivo therapeutic efficacy of P-Dex has been examined in the AA rat model [2,95]. At 14 days post RA induction, the animals with established arthritis were treated with Dex phosphate or P-Dex at an equivalent total dose of Dex (10 mg/kg). Dex phosphate was given by daily i.p. injection for four days (2.5 mg/kg/day), while P-Dex was administered via a single i.v. injection. One day after initial treatment, a significant reduction of joint inflammation was observed in both P-Dex- and Dex phosphate-treated groups. The AA rats exhibited a slightly faster response to Dex phosphate than to P-Dex treatment. An inflammation flare occurred, however, immediately after the cessation of treatment in the Dex phosphate group, while the P-Dex group showed a sustained amelioration of joint inflammation for more than 20 days [95]. At the end of the study, the histopathological features of the hind limbs were examined and graded. Consistent with the results of the clinical measurements, the P-Dex group exhibited significantly lower histopathological scores than the Dex phosphate group, and importantly, no statistical significance was found between P-Dex and healthy control groups. The average ankle joint bone mineral density (BMD) of the animals was also evaluated. Of note, BMD of the P-Dex treated group was similar to the healthy controls. In contrast, the Dex phosphate-treated animals had a significantly lower BMD level, which was similar to the saline-treated controls. Thus, a single treatment with P-Dex was able to provide complete and sustained resolution of the ankle joint inflammation in the AA animal model. The treatment also resulted in structural preservation of the articular bone and cartilage. More recently, the P-Dex treatment has been validated in the CIA model by Quan et al. (unpublished data), and similar efficacy with respect to amelioration of the joint inflammation and damage has been observed.

Similar to P-Dex, a single administration of click PEG–Dex (10 mg/kg of Dex equivalent) also resulted in a sustained amelioration of joint inflammation in AA rats for more than 15 days, whereas Dex phosphate treatment provided only a temporary resolution [21]. Unlike P-Dex, which was able to completely resolve the joint inflammation for more than 20 days post-administration, click PEG–Dex was less efficient in terms of its anti-inflammatory potency and duration. This result might be explained by the following: 1) click PEG–Dex was found to have a slower activation rate than P-Dex according to the in vitro release profiles at pH 5.0; 2) the smaller average MW (17 kDa) and wider PDI (~3.0) of click PEG–Dex may result in its shorter circulation half life and reduced arthrotropism compared to P-Dex; and 3) there may be reduced synoviocyte internalization and consequently less click PEG–Dex retention in the inflamed joints when compared to the HPMA copolymer-based P-Dex [91].

4.3. The mechanism of action of the macromolecular prodrug in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis

Imaging studies indicate that the arthrotropism of the macromolecular prodrugs in inflammatory arthritis animal models can be attributed to the prolonged circulation half-life of the prodrug and the vasculature leakage associated with articular inflammation [19–21]. What cannot be explained, however, is the sustained suppression of inflammation and resolution of the arthritis with a single injection of the prodrug (>20 days). As stated earlier, it has been found that the lymphatic drainage in the inflamed joints of the arthritis models is normal or even accelerated [17,18]. To solve this apparent paradox, extensive immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and cell culture studies were undertaken. Quan et al. labeled the HPMA copolymer carrier with Alexa Fluor® 488 and found that the synoviocytes had internalized the labeled polymer. Using a panel of fluorescent-tagged antibodies, the Alexa Fluor® 488+ cells were identified as mainly type A synoviocytes (macrophage-like) and type B synoviocytes (fibroblast-like). This was further supported by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of the isolated synovial tissue from AA rats following the administration of the labeled polymer. These data indicate that after the macromolecular prodrug extravasates through the leaky vasculature, it is internalized and sequestered by the synoviocytes. Due to the local inflammatory condition, the synoviocytes have been activated and as a result exhibit enhanced endocytic capacity. This concept is supported by our own findings that LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells (a murine macrophage cell line) exhibit more rapid endocytosis of P-Dex compared to non-activated cells [95]. Publications by other groups report similar results when liposomes or MTX–HSA have been employed for treatment of joint inflammation [20,96].

These results suggest a model in which the macromolecular targeting and retention of the prodrugs at the inflamed joints is initiated by their selective extravasation through the leaky vasculature of the inflamed synovial tissues. After leaving the circulation, the produrgs are internalized by the activated synoviocytes, which exhibit enhanced endocytic capacity. During this process, several structural parameter of the prodrug such as the drug loading (alteration of the prodrugs’ lipophilicity), incorporation of an active-targeting moiety (e.g. biotin or folic acid), and the use of different polymeric carriers (HPMA copolymer was found to be endocytosed faster than PEG by fibroblasts [91]) would significantly affect the amount of prodrug that is internalized. As the cell culture data demonstrate, the internalized prodrugs are sorted into lysosomal compartments, where they can be gradually activated via the acidic/reductive environment or the abundant enzymatic activity within the vesicles. We have termed this novel passive targeting mechanism as “ELVIS”, which represents the macromolecular prodrugs’ Extravasation through Leaky Vasculature and the subsequent Inflammatory cell-mediated Sequestration [96]. Though the initial identification of this mechanism has been in inflammatory arthritis animal models, the compositional elements of this mechanism and additional data in other animal models suggests that ELVIS is a generalized targeting mechanism for macromolecular prodrugs in inflammatory conditions.

5. Challenges and opportunities

Compared to the progress in the development of polymeric chemotherapeutic agents, the development of macromolecular prodrugs for inflammatory diseases, such as RA, is still in its infancy. Many challenges are yet to be addressed: (1) although the concept that macromolecularization of anti-inflammatory drugs can potentiate their therapeutic efficacy has been validated, the potential benefits of such an approach in reducing systemic toxicity, has yet to be definitively proven; (2) while the macromolecular prodrugs’ passive targeting to inflammation sites has been explained by the novel ELVIS mechanism, many details of this mechanism still need to be clarified; (3) though this effect was first observed in an inflammatory arthritis model, ELVIS as a general mechanism of inflammation targeting needs to be extrapolated to additional inflammatory diseases; (4) only two well-established anti-rheumatic drugs (Dex and MTX) have been developed into macromolecular prodrugs thus far. With the extrapolation of the ELVIS into other inflammatory diseases, additional novel drug candidates (e.g. kinase inhibitors) need to be evaluated.

5.1. The safety of macromolecular prodrugs

Both MTX and GCs have well known side effects associated with their clinical applications. One of the major design rationales for the development of macromolecular drugs is that by conjugating the drug to a macromolecular carrier, their side effects would be significantly reduced. The general side effects profiles for MTX–HSA are well known since it has been used as a chemotherapeutic agent in cancer patients for many years. In a phase I trial, the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was established for four courses of 50 mg/m2 MTX–HSA administered at weekly intervals for short-term treatment [34]. Due to drug accumulation, a weekly regimen is not suitable for long-term treatment. The administration of 50 mg/m2 MTX–HSA every 2–4 weeks, achieving plasma concentrations between 10 and 20 μmol/L, was proven to be safe and effective, based on observations in the three responding patients. The side effects of MTX–HSA observed in this study did not differ from the side effects commonly observed with conventional MTX treatment. The predominant side effect was grade 1–3 stomatitis. As there was no MTX control in this study, it is not clear if conjugation of MTX to HSA significantly improved its safety profile. But in an earlier report, it was observed that MTX–HSA was more toxic than MTX alone [97]. To date, the MTX–HSA safety profile has not been evaluated in an arthritis model.

Synthetic GCs, act in a similar way to endogenous GCs, which are maintained at a basal level (5.7 mg/m3/day) by secretion from the adrenal gland [98]. The rationale for the application of exogenous GCs in RA management is related to their anti-inflammatory and immuno-suppressive effects [99,100]. GCs suppress the immune system through reducing activation, proliferation, differentiation, and survival of a variety of inflammatory cells (e.g. macrophages and T lymphocytes). GCs exert their pharmacologic effect via genomic mechanisms, in which the internalized GCs bind to their cytosolic receptor, and then translocate to the nucleus where they alter the transcription of GC-responsive genes [101]. Due to the widespread distribution of GC receptors in the body, high-dose or long-term administration of GC leads to diverse side effects (e.g. osteoporosis [102], myopathy [103], predisposition to infections [104], and suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [105], etc.).

By reducing the systemic distribution of the GCs, the macromolecular GC prodrugs significantly reduce the off-target side effects of GC in an inflammatory setting. Preliminary data from the clamp-shock model showed promise that the use of a PVP–Dex conjugate might reduce the systemic immune suppression effects of Dex. For evaluation of the safety profile in inflammatory arthritis, the major practical challenge is the selection of an optimal animal model of arthritis to perform the long-term safety experiments.

Preclinical spontaneous and induced animal models of RA have been established in a variety of species (e.g. rodent, rabbit, dog and monkey) [106]. Although non-rodent models, particularly nonhuman primates, may be the more appropriate model for preclinical investigation due to their close relationship to human RA [107,108], rodent models such as AA, CIA, streptococcal cell wall-induced (SCW) arthritis and most recently the transgenic K/BxN serum transfer models are still the most commonly used models. Despite their similar pathology to human RA, the dominant cytokine pathways and immunologic mechanism differ in each of these models, and the response to specific therapeutic interventions in each of the models does not always recapitulate the results in patients with RA. For instance, MTX showed only marginal efficacy in CIA models and is without an effect in SCW arthritis [106]. Therefore, it is extremely important for investigators to be aware of the efficacy and mechanism of action of the model drugs in each of the animal models, in order to choose an optimal model for evaluating macromolecular prodrugs. Another challenge for the long-term preclinical efficacy and safety evaluation is the limited course of disease in these rodent models. For example, AA rats will undergo gradual self-repair 1-month post induction. This prohibits the investigation of the long-term therapeutic efficacy and toxicities of the macromolecular prodrugs (e.g. GC induced osteoporosis which would need prolonged exposure to be detectable). Although the chronic disease phase can last for months in SCW and CIA arthritis, they each possess their own limitations for long-term evaluation of preclinical efficacy and safety [109]. For example, in the SCW chronic arthritis model, the animals spontaneously develop a hypoactive hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which is also a common side effect associated with GC treatment [110]. For this reason, the SCW model is not suitable for assessing the side effects of long-term treatment with GCs or macromolecular GC prodrugs. At the late stages of CIA arthritis (6 to 8 weeks after onset), many of the pathological characteristics (e.g. presence of inflammatory cell infiltrates in the synovium) of RA improve or disappear. In addition, the time course of disease in the rodent models also affects the experimental design. For instance, the first week after the onset is the most active period of arthritis in the CIA model and MTX exerts its effects only after a treatment period of at least 4 weeks. For this reason, the treatment of the mice with MTX or MTX–HSA had to be initiated before the onset of arthritis in order to evaluate the effect of the treatment on the course of arthritis during the most active period of the disease [30].

An obvious solution to this dilemma would be to use larger animal models, which would more closely resemble the disease pathology of RA, but also the time course of the arthritis development and progression. The apparent limitation of these studies, however, is the animal expense. As an alternative, we recently evaluated the therapeutic efficacy and safety of P-Dex in a lupus nephritis mouse model, which has a much longer disease course (>5 months) than the arthritis models. It was found that the monthly injection of P-Dex would not only resolve nephritis but also was associated with significantly reduced systemic side effects (i.e. bone loss and immunosuppression) when compared with daily Dex treatment (unpublished data). In addition, preliminary data from an acute toxicity study of P-Dex in healthy rats found that the P-Dex treatment resulted in a significantly higher survival rate compared to equivalent doses of Dex phosphate (unpublished data). Hopefully, new inflammatory arthritis rodent models can be developed that will more adequately reflect the disease course of RA in humans. This will permit the necessary preclinical safety evaluation for the macromolecular prodrugs such as P-Dex.

5.2. Elucidation of the macromolecular prodrugs’ arthritis-targeting mechanism

Using the HPMA copolymer system, we have demonstrated that the macromolecular prodrugs’ Extravasation through Leaky Vasculature and the subsequent Inflammatory cell-mediated Sequestration (ELVIS) is responsible for the unique inflammation-targeting property of P-Dex. The data from the MTX–HSA study is also confirmative of this mechanism [20]. However, additional data are needed to fully support this general model. First, both our unpublished data with P-Dex and the results from the MTX–HSA have found that a fraction of the prodrug was internalized by circulating WBCs. The role of these drug-loaded cells in the targeting of the prodrug to the arthritic joints and the resolution of the systemic inflammation is not known. It is possible that these cells may infiltrate the site of inflammation and contribute to local accumulation of the prodrug. Although this mechanism could be associated with the type A synovial cell, which is of myeloid linage, it would not explain the presence of the prodrug in the type B synoviocytes, which are resident cells in the synovium and not likely to be present in the circulation. Second, P-Dex distributes to liver and spleen of arthritic animal after systemic administration. In addition to ameliorating the splenomegaly, the metabolism of P-Dex in these organs and its systemic impact needs to be further elucidated. Third, most of the literature describing the pattern of lymphatic drainage in RA has been derived from early human data [111,112]. The recent studies from the Schwarz laboratory suggest that the lymphatic drainage of low molecular weight contrast agents in animal models of RA is normal or accelerated [17,18]. Further investigation is needed to better understand the macromolecular pro-drugs’ lymphatic drainage. Fourth, the prodrug activation site and mechanism also needs to be verified. In the original design, local acidosis of the synovial tissue and acidic pH within the lysosome were proposed as the triggers for P-Dex cleavage. We have confirmed the synoviocyte sequestration of P-Dex and its subcellular activation using cell culture systems. No direct evidence is available, however, to support the initial extracellular prodrug activation due to tissue acidosis. Fifth, the impact of chronic inflammation on the macromolecular prodrug targeting of affected joints has yet to be investigated. It is possible that at different time points after the onset of inflammation, the local vasculature structure and inflammatory cell infiltrate composition will be different; and this may alter the pattern and sequestration of the prodrug. An understanding of these issues is essential for the identification of the optimal treatment window for the application of the macromolecular prodrug paradigm.

5.3. Extrapolation of ELVIS to other inflammatory diseases

Similar to arthritic joints, inflammatory tissues in multiple disorders share similar pathophysiological features such as vascular leakage, as well as the presence of activated inflammatory cells. Therefore, we speculate that the ELVIS effect is also applicable in these other inflammatory disorders. Recently, Ren et al. used P-Dex for the treatment of orthopedic wear particle-induced osteolysis in a murine model [113]. Clinically, wear particle-induced inflammation is a major cause of aseptic implant loosening after total joint replacement. The data from this study showed that P-Dex specifically distributed to the particle-induced sites of inflammation in an animal model and ameliorated the particle-induced local bone resorption. In addition to therapeutic benefits, the authors also proposed that the HPMA copolymer system could be used as a theranostic tool for early diagnosis and prevention of implant loosening. Because of the diverse pathophysiology associated with inflammatory and auto-immune disorders it is likely that adjustments in the chemistry and design of prodrugs will be needed to select the optimal structural parameters for the prodrug carrier, the activation mechanism and the drug candidates.

5.4. Selection of drug candidate for macromolecularization

The model drugs that have been developed into macromolecular prodrugs so far have favorable functional groups for their conjugation to the carriers. Therefore, the availability of a modifiable chemical handle in the drug structure becomes the first criteria in selecting a drug for macromolecularization. If no structure is available, an analog of the parent drug may have to be synthesized to introduce functionality. In this case, the biological function of the analog must be validated prior to its conjugation to the polymeric carrier. The potency of the drug is the second factor that needs to be considered. Different from other colloidal delivery systems, the drug content of the macromolecular prodrugs is limited (for the HPMA copolymer, it is typically less than 10 mol% to avoid inter/intra-molecular micellization or aggregation). Therefore, drugs with higher potency would not require a high loading in the prodrug design. As the prodrugs’ activation mechanism is often designed according to particular pathological conditions, a potent drug may achieve a better safety profile, because its activation will be more closely regulated when compared to other colloidal delivery systems. Lastly and most importantly, the drug candidate must be selected according to its intended application. For each inflammatory disease, there will be optimal drug candidates that are uniquely targeted to the underlying disease pathology, and this principle must guide the design strategy of the prodrug.

This last principle is particularly relevant to the application of the prodrug strategy for RA in which there has been great interest in the development of small molecule inhibitors that target intra-cellular kinase signaling pathways. Molecular and genetic screening have defined the tissue distribution and specificity of the individual kinases that comprise the major signal pathway families associated with inflammatory and autoimmune processes, including the MAP, JAK, SYK, and NF-κB pathways. Each signaling pathway involves sequential activation of a series of protein kinases that play important roles in the pathogenic processes of RA. High-throughput screening and drug design methodologies have identified small molecule inhibitors to target specific protein kinases within these pathways, and studies in animal models of inflammation and in early human trials have validated their clinical efficacy [114]. However, the requirements for high dosages, frequent administration, and undesirable PK/BD and toxicity profiles associated with adverse effects on “off target” tissues remain a major barrier to the advancement of these therapeutic agents into actual clinical application. For example, p38, one of the terminal kinases that regulate cellular responses in the MAP signaling pathway, was proposed as therapeutic target in RA therapy. However, the first generation of p38 inhibitors failed in clinical trials due to liver, brain and skin toxicities [114]. These limitations would make macromolecularization of kinase inhibitors a very promising direction to pursue. From the chemistry conjugation aspect, it is fortunate that the structures of most kinase inhibitors possess suitable functionalities (i.e. primary or secondary amine, hydroxyl and ketone groups), which would allow chemical modification and macromolecularization.

6. Expert perspective

The development of macromolecular prodrugs for inflammatory diseases, especially RA, is a new and very promising direction for the design and development of polymer therapeutics. In this manuscript, the design principles of a series of macromolecularized anti-RA drugs have been summarized and discussed, even though many of them were not proposed for RA therapy or have not yet been evaluated in preclinical arthritis models. Although these prodrugs are primarily designed with an activation mechanism triggered by pathophysiology-associated enzymes or an acidic environment, knowledge of the precise mechanisms that control their rate and site of activation are still missing. Well-controlled linkage chemistry and accurate in vivo activation profiles are essential for maintaining the safety of these prodrugs. In addition, the simplicity of the chemical design should never be neglected, considering the reproducibility and expense in scale-up production as well as the efficiency of clinical translation. A body of published data from our own laboratories and others strongly suggest that this strategy would significantly expand the repertoire of the current anti-rheumatic/anti-inflammatory drugs and likely reduce their systemic toxicity. In order to advance the development of this strategy and to accelerate the translation of the findings into clinical application, there is a need for a thorough evaluation and long-term study of the efficacy and toxicities for these prodrugs in relevant and reliable animal models. The successful application of macromolecular prodrugs in preclinical inflammatory arthritis models can be attributed to the newly defined inflammation targeting mechanism, which we have designated as “ELVIS”. As stated in Section 5.2, however, several questions need be answered to fully elucidate this mechanism. A thorough understanding of this mechanism would not only benefit the design of the macromolecular prodrugs for RA treatment, but also permit the extension of this targeting concept into the treatment of many other inflammatory diseases. Therefore, we believe the further dissection of this novel inflammation targeting mechanism and its validation with additional anti-rheumatic agents will make a significant contribution to the future development of macromolecular prodrugs for improved treatments of rheumatoid arthritis and related inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by National Institute of Health R01 AR053325.

Footnotes

This review is part of the Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews theme issue on “Targeted delivery of therapeutics to bone and connective tissues”.

References

- 1.Quan LD, Thiele GM, Tian J, Wang D. The development of novel therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2008;18:723–738. doi: 10.1517/13543776.18.7.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu XM, Quan LD, Tian J, Alnouti Y, Fu K, Thiele GM, Wang D. Synthesis and evaluation of a well-defined HPMA copolymer–dexamethasone conjugate for effective treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2910–2919. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9683-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allaire S, Wolfe F, Niu J, Lavalley MP. Contemporary prevalence and incidence of work disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis in the US. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:474–480. doi: 10.1002/art.23538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez A, Maradit KH, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Davis JM, III, Therneau TM, Roger VL, Gabriel SE. The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3583–3587. doi: 10.1002/art.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrera P, Blom A, van Lent PL, van Bloois L, Beijnen JH, van Rooijen N, de Waal Malefijt MC, van de Putte LB, Storm G, van den Berg WB. Synovial macrophage depletion with clodronate-containing liposomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1951::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards P, Williams B, Williams A. Suppression of chronic streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis in Lewis rats by liposomal clodronate. Rheumatology. 2001;40:978–987. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]