Abstract

Objective

To demonstrate the feasibility of using Multi-Detector Computed Tomography with gadolinium (Gd) contrast (Gd-MDCT) for the quantification of myocardial infarct (MI).

Materials and Methods

MI was induced in six male swine (n=6). One week later, the animals received 0.2mmol/kg gadopentetate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA) and were sacrificed. On the excised hearts, Gd-MDCT with several tube voltages (80, 120 and 140kV), Late Gadolinium Enhancement MRI (LGE-MRI), and triphenyl-tetrazolium-chloride (TTC) staining were then conducted. We used a 2SD threshold for the CT images, and several threshold limits (2, 3, 4, 5, 6SD and FWHM) for the LGE-MRI images, to delineate the infarct area. Total infarct volume and infarct fraction (IF) of each heart were calculated.

Results

MI size measured by MDCT at 140kV showed good correlation with the reference TTC value. Applying an 80kV tube voltage, however, significantly underestimated MI size. In our study, the LGE-MRI method, using the 6SD threshold provided the most accurate determination of MI size. LGE-MRI, using the 2 and 3SD threshold limits, significantly overestimated infarct size.

Conclusions

The Gd-MDCT technique has been found suitable for the evaluation of MI in an ex-vivo experimental setting. Gd-MDCT has the ability to detect MI even at low kV settings, but accuracy is limited by a high image noise due to reduced photon flux.

Keywords: Myocardial Infarct, Gadolinium-based Contrast Medium, Multi-detector Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging

INTRODUCTION

Iodine-based contrast media (CM) can be used safely for X-ray and Computed Tomography (CT) studies in most patients. Adverse effects caused by iodine exist in 0.15% of cases, as described in a retrospective review based on almost 300,000 patients.[1] In such patients, the use of either a different imaging technique or an alternative CM may be required. As alternatives to iodine CM, Carbon-dioxide, Xenon, and Gadolinium-chelates (Gd) have been studied and successfully applied in select X-ray and CT examinations.[2, 3] In the field of cardiovascular radiology, Gd-chelates have become the most investigated potential CM.

Gd is the element with atomic number 64 (atomic weight 157), while iodine’s atomic number is 53 (atomic weight 127). X-ray attenuation increases with atomic number and decreases with the energy of the X-ray photons in a nonlinear fashion. For CT studies, the maximum X-ray photon energy is 140keV. The attenuation by Gd in this setting is twice that of iodine, but since there are 3 iodine atoms in each iodine-based CM molecule (e.g. Omnipaque), the iodine CM attenuates 1.5 times more radiation than does a typical Gd chelate CM.[4]

The first use of Gd-chelates as radiographic CM in CT studies was reported in 1989 by Janon and Bloem et al.[5, 6] Since then, several cases using Gd-chelates in various radiographic procedures have been published. Furuichi et al. reported the use of gadopentetate dimeglumine, Gd-DTPA, in the course of percutaneous coronary intervention.[7] Gupta et al. studied the thoracic aorta, and cervical and abdominal vessels, by 3D CT Angiography (CTA) (280mAs, 120-140kV) using 0.3mmol/kg Gd-DTPA- and found sufficient contrast to clearly define these vessels.[8] Kälsch et al. studied 19 patients with contraindication to iodinated CM and found reduced but acceptable image quality for diagnostic purposes using Gd-based CM in coronary angiography.[9] A review article by Strunk et al. on the use of Gd-DTPA for non-MRI applications concludes that Gd-based CM could be safely used for radiography. It is, however, presently approved for MRI use only.[10]

Using CT with Gd as contrast medium for the detection or quantification of myocardial infarct (MI) has not yet been reported. The aim of this ex vivo study was to investigate the ability of Multi-detector CT using Gd-DTPA as contrast medium (Gd-MDCT) to evaluate MI, and compare the results with data obtained by the in-vivo gold standard Delayed Enhancement Magnetic Resonance Imaging (LGE-MRI) and the ex-vivo gold standard triphenyl-tetrazolium-chloride (TTC) staining method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental model

Study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, University of Alabama at Birmingham) and complied with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health). MI was generated in six male swine (n=6, ~25-30kg) under Isoflurane anesthesia (2.0–3% V/V) by a 90-minute long percutaneous balloon occlusion of the Left Anterior Descending (LAD) coronary artery. Reperfusion of the coronary artery was confirmed by repeated angiography. One week later, the animals received 0.2mmol/kg Gd-DTPA (Magnevist®, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc, Wayne NJ) by bolus injection and were sacrificed 20 minutes later using 100mg/kg sodium pentobarbital and 2mmol/kg KCl. Euthanasia was monitored by ECG and auscultation above the thorax. Hearts were immediately excised following the successful euthanasia. Excised hearts were rinsed in physiologic saline and hung up on a stand to set the annulus fibrosus in a horizontal position. (Fig. 1) To provide a horizontal reference plane for angulation and reconstruction, 1ml of a 10% V/V Gd-DTPA solution was mixed with a 20ml agar solution, layered into the bottom of a 1000ml beaker, and separated by a 50μm thick plastic foil to prevent free upward diffusion of Gd-DTPA. Hearts were then placed in the beaker and embedded in 4.2% agar gel (Nutrient Agar, Remel Inc., Lenexa KS) providing a stable position for the heart structures during the imaging sessions. Same day Gd-MDCT, LGE-MRI, and TTC-staining were then conducted.

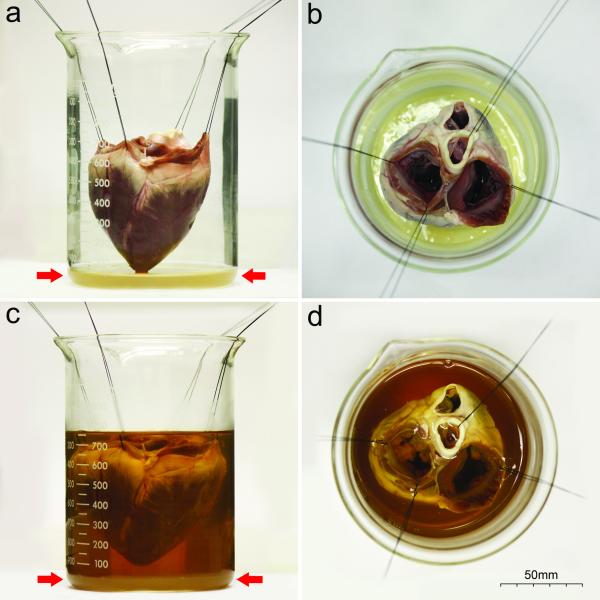

Fig. 1.

Embedding procedure of the heart

Lateral (a, c) and superior (b, d) views of the beaker. The heart is hanged on a stand using four silk surgical sutures (a, b). Red arrows show the Gd-DTPA containing agar layer which provides the horizontal reference plane during the angulation (MRI). After setting the heart to the proper position, the beaker is filled with 40°C agar solution (c, d)

MDCT

MDCT studies were carried out immediately following the embedding procedure of the heart using a Philips Brilliance 64 scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Images were collected covering the entire beaker using the following parameters: tube voltage=80/120/140kV, tube current=600mA, Image Matrix (IM)=512×512; Field of View (FoV)=160mm; Slice Thickness (ST)=1mm; increment=0.5mm. Short axis oriented reconstruction process (ST=1mm) was aided by the bottom of the radiopaque beaker providing the same image orientation as obtained by MRI.

MRI

MRI acquisitions were conducted following the MDCT sessions using a 1.5T GE Signa-Horizon CV/i scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a head-coil. Since the glass beaker itself is invisible by MRI, the Gd-DTPA-containing bottom layer was used to aid the angulation process by serving as a reference plane. Using an inversion recovery, 180°-prepared, fast gradient echo pulse sequence, multi-slice short axis oriented LGE images (TE/TR/flip=3.1/7.1/25°; shot repetition time=2000ms; IM=256×256; FoV=160mm; ST=5mm) were acquired covering the entire heart. The inversion time (TI) was selected from the range of 200-400ms, where the signal was nearly null in the viable myocardium.

TTC staining

Following the imaging sessions, hearts were frozen and bread-sliced (5mm), based on the orientations of the tomographic slices, using a commercial meat slicer. Subsequently, the slices were incubated for 20min with a buffered (pH=7.4) 1.5% TTC solution at 37°C, as described by Fishbein et al.[11] Following staining, slices were immersed in 10% formalin for 20 minutes to increase the contrast between healthy and infarcted myocardium. Finally, both surfaces of each slice were scanned with a Lexmark X1270 digital scanner (Lexmark International Inc., Lexington KY) connected to a personal computer.

Histopathology

After scanning the TTC stained slices, tissue samples were prepared from the infarct, peri-infarct, and healthy myocardial regions of the left ventricle (LV) to confirm the existence of MI by microscopic histopathology. The samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5μm thickness, and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E).

Image analysis

MDCT and MRI dicom images were imported as image sequences with the use of ImageJ v1.42 software (Wayne Rasband, NIH). Images were cropped and vertical stacks were created. The mean MRI signal intensity (SI) or CT attenuation of the remote (i.e. viable) myocardium (SIremote), the mean SI (or attenuation) of the most intense portion of the hyperenhanced area corresponding to the infarcted myocardium (SIinfarct), and the mean SI of the background noise (area on the image but outside the beaker) (SInoise) were measured with multiple regions of interest.

To compare the image quality provided by MDCT vs. MRI, the signal to noise ratio (SNR), contrast to noise ratio (CNR), and signal intensity ratio (SIR) were calculated using the following definitions:[12, 13]

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where SImean is SIinfarct or SIremote (or CT attenuation), and SDnoise is the standard deviation (SD) of the signal intensity of background air. Due to the Rayleigh distribution of the background noise in magnitude images, equation 1 was corrected with the factor of (≈1.53) in case of MRI images.[12]

For further analysis, the endocardial and epicardial contours of the LV were traced manually to delineate the total myocardial area. Myocardial pixels were counted, and based on the pixel dimensions the myocardial volume of each slice was determined, from which the total LV myocardial volume was also calculated (LVV). To avoid observer bias, instead of manual contouring of the infarct region, the thresholding technique was used to delineate MI as follows.

Since there is no agreement in the literature which thresholding technique provides the most accurate evaluation of MI, we used several methods for infarct quantification in the MRI images. Mean SI of the remote plus 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 times the SD, and the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) method were used to define the threshold limit.[14-19] In each case, pixels with SI above the specific threshold limit were considered infarct pixels.

For MDCT images, infarct pixels were observed as HU elevations due to the increased presence of Gd-DTPA in such pixels. Mean attenuation of the remote areas plus 2 times the SD was used to threshold the images. Each 1mm thick slice was evaluated.

In the thresholded images infarct pixels were counted and the infarct volume of each slice was determined, from which the total infarct volume of each heart (IV) was calculated and expressed as a percentage (Infarct Fraction, IF) of the LVV.

Both the apical and basal surfaces of each TTC stained slice were analyzed. The LV myocardium and the infarct area were manually contoured and quantified. LVV, IV and IF were determined in each heart.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SigmaStat v2.03 (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL). Data were expressed as mean±SD. Normality and equal variance tests were used to determine whether a parametric or nonparametric statistical method should be applied. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare results among the imaging methods and the TTC-staining, and Holm-Sidak multiple comparison analysis was applied for pairwise comparison. Bland-Altman plots were used to analyze the accuracy of each technique. When a significant difference was observed among parameters (IVs, IFs) obtained by the different techniques, the value of over- or underestimation was calculated by comparing the results to the reference TTC. Comparison of CNR, SNR, and SIR among the different MDCT settings and MRI was carried out using one-way ANOVA. Post hoc statistical power was calculated using the power analysis for ANOVA with a type-I error rate (α) of 0.05. Rejecting the null hypothesis at this level of α with a P-value <0.05 will be interpreted to indicate a significant difference.

RESULTS

Raw and post-processed corresponding images from a representative heart are shown in Fig. 2 and 3. All three techniques provided sufficient image quality to visualize MI. Microscopic evaluation of the tissue samples confirmed the existence of MI. The average attenuation, SI, the calculated SNR, CNR, and SIR values are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Sample image sets of a representative heart slice

Corresponding ex-vivo, short-axis oriented, raw and post-processed MDCT images are shown. Raw MDCT images obtained by 80 (a), 120 (b) and 140kV (c) (same window/level) are shown in the first row. The area of the MI delineated by the thresholding method is highlighted in the bottom row (d-f).

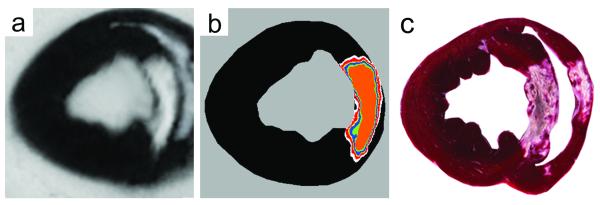

Fig. 3.

MRI and TTC

Raw (a), thresholded LGE-MRI (b), and corresponding TTC images are shown. The area of the MI delineated by various thresholds of the MRI image (b) is shown superimposed on the image. The color codes are the following: black (remote), white (2SD), red (3SD), yellow (4SD), blue (5SD), green (6SD), and orange (FWHM).

Table 1.

Average attenuation (HU) and SI (arbitrary units, au) values, and calculated SNR, CNR and SIR in MDCT and MRI images, respectively (mean±SD)

| MDCT |

MRI |

P-value MDCT vs. MRI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80kV | 120kV | 140kV | |||

| Background | −1009±2.5 | −1010±2.1 | −1009±2.6 | 144±10.2 | |

| Remote | 43±1.9 | 42±1.9 | 42±2.0 | 168±12.5 | |

| Remote SD | 16±0.9 | 8±0.5 | 6±0.5 | 16±4.2 | |

| Infarct | 91±6.2 | 81±5.1 | 80±5.0 | 734±118.1 | |

| Infarct peak | 133±16.1 | 109±12.3 | 100±5.4 | 921±42.4 | |

| SNR remote | 4.0±0.3 | 4.5±0.6 | 4.6±0.5 | 10.7+4.5 | <0.05 |

| SNR infarct | 8.5±1.0 | 8.8±1.1 | 8.8±1.2 | 46.9+11.2 | <0.05 |

| CNR | 4.5±0.7 | 4.3±0.8 | 4.2±0.7 | 36.2+6.1 | <0.05 |

| SIR | 2.1±0.2 | 1.9±0.1 | 1.9±0.1 | 4.4+0.7 | <0.05 |

Comparing the MDCT images obtained by the three different kV settings, the mean of the background air and the remote myocardium showed statistically the same average attenuation independently of tube voltage. The SD of the remote myocardium (i.e. the noise of the remote areas) showed a strong linear relationship (R2=0.9999) with (kV)−1.3.[20] The background noise showed a similar correlation (R2=0.9786). Mean MI attenuation values at 80kV were significantly higher (P<0.01) than at 120 or 140kV, while no statistical difference was observed between the latter two. SNRremote was significantly lower at 80kV (p<0.05) than at the other two tube voltages, while no difference was observed between 120 and 140kV. There was no statistical difference among the SNRinfarct, CNR and SIR values measured at the different kV settings. All these ratios were significantly lower than ratios measured by MRI (P<0.001, power of 0.902).

Average LVV, IV and IF values measured by MDCT, MRI and TTC are shown in Table 2. Average LVVs obtained by the different techniques were in good agreement (P=N.S.) with each other indicating that all these techniques provide comparable volumetric data. The multiple comparison method showed that MDCT80kV, LGE-MRI with 2 and 3SD thresholds are significantly different from the reference TTC (p<0.05), while no statistical difference was observed among IVs and IFs obtained by MDCT120kV, MDCT140kV, MRI4SD, MRI5SD, MRI6SD, MRIFWHM and TTC. (Fig. 4)

Table 2.

Average LVV, IV, and IF (%) values (mean±SD) measured by each technique. Results were compared to the reference TTC

| Modality | Tube voltage (kV) |

LVV (ml) |

IV (ml) |

IF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDCT | 80 | 72.06±13.23* | 1.65±1.24 | 2.34±2.11 |

| 120 | 3.80±1.78 | 5.36±2.01 | ||

| 140 | 5.06±1.64 | 7.15±2.28 | ||

|

| ||||

| Threshold | ||||

|

| ||||

| MRI | 2SD | 74.72±13.15* | 8.91±2.99 | 12.03±3.81 |

| 3SD | 8.07±1.15 | 10.80±1.89 | ||

| 4SD | 7.22±1.31 | 9.66±1.49 | ||

| 5SD | 5.87±1.26 | 7.86±2.03 | ||

| 6SD | 5.47±1.23 | 7.36±1.57 | ||

| FWHM | 4.36±1.16 | 5.86±1.55 | ||

|

| ||||

| TTC | 75.42±14.85 | 5.36±1.57 | 7.34±2.30 | |

The LV volume was calculated only once with each method, since the same endo- and epicardial contours were used for each kV (MDCT) or threshold (MRI)

Fig. 4.

Comparison of IFs

IFs obtained by the different methods are shown by a bar diagram. IFs were compared to the reference TTC. Significant difference is indicated by an asterisk.

Bland-Altman plots of IF obtained by MDCT and MRI vs. TTC are shown in Fig. 5. The plots indicate good agreement for the IF values obtained by MDCT120kV, MDCT140kV, MRI5SD, MRI6SD and MRIFWHM vs. the gold standard TTC method. Note, that the mean of differences (i.e. bias) is less than 1% in the case of MDCT140kV and MRI6SD, and less than 2% with MDCT120kV, MRI5SD and MRIFWHM. The Bland-Altman analysis of MDCT80kV showed a bias of −5.07% (~3.7ml) indicating a significant underestimation of the IF by this method. Plots of the MRI data with 2, 3 and 4SD thresholding showed overestimation of the IF with a bias of 4.68% (~3.41ml), 3.50% (~2.61ml) and 2.31% (~1.72ml), respectively.

Fig. 5.

Bland-Altman plots

Bland-Altman plots of IF obtained by MDCT with various tube voltages (first raw) and MRI with various thresholds (second and third rows) vs. TTC are shown. Dashed lines indicate the upper and lower 1.96SD interval.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated in an ex-vivo experimental model that quantification of MI using the Gd-MDCT technique is feasible, providing accurate evaluation of MI size as judged by the in-vivo gold standard LGE-MRI, and the ex-vivo gold standard TTC method.

We have also demonstrated that the agar embedded ex-vivo heart model is suitable for the performance of repeated, or multi-modality, imaging, when a stable position of the sample is required. A similar technique was used by Dahele et al to study small lung specimens.[21]

The SNR, CNR, and SIR results of our ex-vivo MRI studies were in good agreement with other investigators’ in-vivo findings.[22, 23] Measurement of these parameters in infarcted myocardium by Gd-MDCT has not been published previously. Our results (Table 1) showed that all three parameters (SNR, CNR, and SIR) obtained from Gd-MDCT images were significantly lower than those obtained from LGE-MRI images. CNR was ~8 times higher in MRI than in Gd-MDCT. SIR in MDCT images was also inferior to that in LGE-MRI. Thus, the dynamic range of attenuation (the range between the remote and infarcted myocardium) is restricted in Gd-MDCT compared to MRI. Nevertheless, Gd-MDCT still provided sufficient contrast to distinguish between normal and infarcted myocardium.

The MI was visually detectable by Gd-MDCT at all settings. The measured MI size, however, depended on the tube voltage used. The mean attenuation of the MI was highest at 80kV, but the increase of the noise in the remote myocardium, was a much more dominant change caused by the reduction in voltage. The noise in the remote myocardium influenced the accuracy of the MI quantification because the thresholding level depended on the myocardial noise. The noise in the remote myocardium was linearly proportional to (kV)−1.3, thus the image noise decreased with higher kV settings.[20]

In this study, we found that MI size measured by Gd-MDCT at 140kV showed good correlation with the reference TTC. Applying 80 or 120 kV tube voltages, however, underestimated MI size. The underestimation is surprising at first, since the peak and mean attenuation of the MI is highest at the level of 80kV, and iodine studies also indicate that the accuracy of MI size determination is better with a low tube voltage.[13] This finding, however, can be explained by the fact, that the noise of the remote myocardium is increased at lower tube voltages (detailed above). There are areas in the MI where the accumulation of the Gd is restricted or decreased: areas of microvascular obstruction (MO) in the center of the infarct or peri-infarct zones with patchy infarct and normal perfusion. In those areas, the amount of Gd is either below the detectable limit, or the attenuation associated with the Gd is within the remote noise limit. When the noise of the remote is increased, more areas with moderate Gd accumulation are considered as noise and only the infarct core areas with high Gd content are highlighted.

In our study, the LGE-MRI method, using the higher 5 or 6SD thresholds, provided accurate determination of MI, as also described previously.[14-16, 19] LGE-MRI6SD provided the closest result to the reference TTC value. LGE-MRI using the other threshold limits overestimated (2, 3, 4 SD) or underestimated (FWHM) the infarct size. The reason for infarct overestimation using DE may be due to the partial volume effects mostly presenting in the patchy peripheral zone of the infarct, while underestimation is the likely result of excess filtering out of useful infarct data.

Our finding that Gd-MDCT at high tube voltage with 2SD thresholding yielded more accurate results than the widely used LGE-MRI with the same thresholding, may be due to several reasons. The spatial resolution of MDCT is higher than that of MRI. The voxel volume [(FoV2/IM)*ST] in our study was 0.1mm3 (MDCT) vs. 1.95mm3 (MRI), resulting in a negligible partial volume effect in MDCT, but not in MRI. The areas affected by partial volume effect usually consist of the patchy peri-infarct zones where the Gd distribution is highly inconsistent.[24] Another reason is the difference between the mechanisms of the contrast effect of Gd-DTPA in these two imaging modalities. In MRI, Gd-chelates act as a contrast agent, since they exert an effect on the protons of the tissue water molecules, and this effect is observed as SI enhancement by MRI. SI enhancement induced by a Gd contrast agent depends nonlinearly on the concentration of the contrast agent in the myocardial voxel observed.[25, 26] In CT, Gd works as a contrast medium. The high atomic weight of Gd (157) makes it radiopaque, thus its simple physical presence, and not an indirect effect on another molecule, is measured. Infarct determination by Gd-MDCT is straightforward since Gd concentration in any voxel is related to the attenuation in a linear fashion, as described in phantom studies.[27]The literature suggests that the diagnostic value of Gd-based CT techniques is inferior to the iodine based methods.[8-10, 28] Although it is evident that Gd-MDCT provides less contrast than Gd-MRI or iodine CT, our results, nevertheless, proved the presence of sufficient contrast for distinguishing between normal and infarcted myocardium using 0.2mmol/kg Gd-DTPA.

In conclusion, the Gd-MDCT technique has been found suitable for the evaluation of MI, at least in an ex-vivo experimental setting. Gd-MDCT has the ability to detect MI even at low kV settings with accuracy being limited by high image noise due to reduced photon flux. LGE-MRI showed its best accuracy at the threshold level of 6SD.

Practical implications

The ability of Gd-MDCT to detect MI has been proven here in an ex vivo animal model. The usefulness of this method in in vivo circumstances, however, depends on several additional factors (e.g. imaging a rapidly moving heart) whose evaluation requires in vivo experiments.

A further issue with Gd-MDCT is the lack of approval of Gd-chelates for non-MRI purposes which is strongly influenced by the question of the safety of the administration of Gd containing materials. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) is a potentially severe systemic disease characterized by fibrosis of the skin and connective tissues. Based on a review, 89% of patients with NSF underwent Gd injection prior to the onset of the disease, thus Gd CM can be considered as a trigger of NSF.[29] It is hypothesized that the prolonged presence of the agent in tissue increases the risk of de-chelation, initiating fibroblastic reaction. Since the rate of de-chelation highly depends on the stability of the complex, the less stable, non-ionic linear complexes (e.g. gadodiamide) are the most highly associated with the development of NSF.[29] Although ionic linear complexes (e.g. Gd-DTPA) are more stable, they are also responsible for some NSF cases. The odds ratio of the risk of NSF with gadodiamide is 13.2 times greater than with Gd-DTPA.[29] Cyclic Gd chelates (e.g. gadoteridol) have extremely high stability, and indeed they are not associated with NSF. Also, NSF only occurs in patients with severe renal impairment (82% of NSF patients were on dialysis, 27% had a renal transplant), thus the administration of linear complexes is contraindicated in such patients (GFR<30).[30] Based on the safety of the cyclic Gd-chelates suggesting by the presently available literature, those chelates may have a chance to get approval for non-MRI applications.

The experimental benefit of Gd-MDCT is the ability to measure the exact Gd concentration of a specific voxel. It has been proven that MI is not a solid, confluent non-viable mass; rather it is a mixture of viable and non-viable islets with varying density of the viable components.[24, 31, 32] CT phantom studies showed that Gd concentration of any voxel is related to the attenuation in a linear fashion, i.e. the Gd concentration of the voxel observed can be determined by the attenuation measured in the same voxel.[27] MRI phantom experiments have proven that R1 (the inverse of T1) of an infarct voxel is related to the Gd concentration of the same voxel in a linear fashion.[26] Along with proper co-registration, the Gd-MDCT method has the potential to enable the study of the in vivo correspondence between the Gd concentration (i.e. CT density) and the relaxation rate (i.e. MRI R1 intensity) in the infarcted heart.

Presently, the clinical benefits of Gd-MDCT are mostly theoretical. Although, Gd-MDCT has the ability to detect MI, numerous alternative techniques (e.g. DE-MRI, 201Tl, 99mTc-sestamibi or 99mTc-tetrafosmin SPECT, 18F-deoxy-glucose PET etc.) have been developed to noninvasively distinguish viable myocardium from irreversibly injured myocardium, and to localize, visualize, and quantify MI.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. The presented data were obtained from ex-vivo, agar embedded hearts. This model does not fully mimic the in-vivo environment of the heart, thus our results may not be completely applicable for in-vivo situations. Also, MI was studied 7 days following reperfusion, thus the obtained data are not necessarily applicable for all phases of the evolution of MI. There are superior, multiple identical acquisition-based methods available to calculate SNR from MRI data, those methods, however, were not applicable to our studies as we carried out single image acquisitions. A further limitation is the lack of approval at the present time of Gd-chelates for non-MRI purposes.

Acknowledgments

Source of support: This study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Grant# 5R42 HL080886-03).

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt CH, Hartman RP, Hesley GK. Frequency and severity of adverse effects of iodinated and gadolinium contrast materials: retrospective review of 456,930 doses. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1124–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahnken AH, Penzkofer T, Grommes J, et al. Carbon dioxide-enhanced CT-guided placement of aortic stent-grafts: feasibility in an animal model. J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:332–9. doi: 10.1583/09-2969R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chae EJ, Seo JB, Lee J, et al. Xenon Ventilation Imaging Using Dual-Energy Computed Tomography in Asthmatics Initial Experience. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:354–61. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181dfdae0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomsen HS, Almen T, Morcos SK. Gadolinium-containing contrast media for radiographic examinations: a position paper. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2600–5. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1628-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janon EA. Gadolinium-DPTA: a radiographic contrast agent. Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:1348. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.6.1348-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloem JL, Wondergem J. Gd-DTPA as a contrast agent in CT. Radiology. 1989;171:578–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.2.2704827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuichi S, Yasuda S, Arita Y, et al. Gadopentetate dimeglumine as a potential alternative contrast medium during percutaneous coronary intervention: a case report. Circ J. 2004;68:972–3. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta AK, Alberico RA, Litwin A, et al. Gadopentetate dimeglumine is potentially an alternative contrast agent for three-dimensional computed tomography angiography with multidetector-row helical scanning. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:869–74. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalsch H, Kalsch T, Eggebrecht H, et al. Gadolinium-based coronary angiography in patients with contraindication for iodinated x-ray contrast medium: a word of caution. J Interv Cardiol. 2008;21:167–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strunk HM, Schild H. Actual clinical use of gadolinium-chelates for non-MRI applications. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:1055–62. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishbein M, Meerbaum S, Rit J, et al. Early phase acute myocardial infarct size quantification: validation of the triphenyl tetrazolium chloride tissue enzyme staining technique. Am Heart J. 1981;101:593–600. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietrich O, Raya JG, Reeder SB, et al. Measurement of signal-to-noise ratios in MR images: influence of multichannel coils, parallel imaging, and reconstruction filters. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:375–85. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahnken AH, Bruners P, Muhlenbruch G, et al. Low tube voltage improves computed tomography imaging of delayed myocardial contrast enhancement in an experimental acute myocardial infarction model. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:123–9. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000251577.68223.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amado LC, Gerber BL, Gupta SN, et al. Accurate and objective infarct sizing by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in a canine myocardial infarction model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beek A, Kuhl H, Bondarenko O, et al. Delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for the prediction of regional functional improvement after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:895–901. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00835-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondarenko O, Beek AM, Hofman MB, et al. Standardizing the definition of hyperenhancement in the quantitative assessment of infarct size and myocardial viability using delayed contrast-enhanced CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2005;7:481–5. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-200053623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fieno DS, Kim RJ, Chen EL, et al. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of myocardium at risk: distinction between reversible and irreversible injury throughout infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1985–91. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00958-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, et al. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, et al. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:1445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul J, Krauss B, Banckwitz R, et al. Relationships of clinical protocols and reconstruction kernels with image quality and radiation dose in a 128-slice CT scanner: Study with an anthropomorphic and water phantom. Eur J Radiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.078. (Article in Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahele M, Hwang D, Peressotti C, et al. Developing a methodology for three-dimensional correlation of PET-CT images and whole-mount histopathology in non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:62–9. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i5.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapon C, Herlihy AH, Bhakoo KK. Assessment of myocardial infarction in mice by late gadolinium enhancement MR imaging using an inversion recovery pulse sequence at 9.4T. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatli S, Zou KH, Fruitman M, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging technique for myocardial-delayed hyperenhancement: a comparison with the two-dimensional technique. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20:378–82. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirschner R, Varga-Szemes A, Brott BC, et al. Quantification of myocardial viability distribution with Gd(DTPA) bolus-enhanced, signal intensity-based percent infarct mapping. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29:650–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suranyi P, Kiss P, Brott BC, et al. Percent infarct mapping: an R1-map-based CE-MRI method for determining myocardial viability distribution. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:535–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritz-Hansen T, Rostrup E, Ring PB, et al. Quantification of gadolinium-DTPA concentrations for different inversion times using an IR-turbo flash pulse sequence: a study on optimizing multislice perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;16:893–9. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puderbach M, Risse F, Biederer J, et al. In vivo Gd-DTPA concentration for MR lung perfusion measurements: assessment with computed tomography in a porcine model. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2102–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gul KM, Mao SS, Gao Y, et al. Noninvasive gadolinium-enhanced three dimensional computed tomography coronary angiography. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:840–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prince MR, Zhang HL, Roditi GH, et al. Risk factors for NSF: a literature review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:1298–308. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document for safe MR practices: 2007. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1447–74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simor T, Suranyi P, Ruzsics B, et al. Percent Infarct Mapping for Delayed Contrast Enhancement MR Imaging to Quantify Myocardial Viability by Gd(DTPA) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32:859–68. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuleri KH, Centola M, George RT, et al. Characterization of peri-infarct zone heterogeneity by contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography: a comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]