Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated clinical features and survival outcomes among patients with signet ring and mucinous histologies of colorectal adenocarcinoma using data from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB).

Methods

Patients aged 18–90 years with colorectal adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 1998 and 2002 were identified from the NCDB. Site-stratified (colon vs rectum) survival analysis was performed using multivariate relative survival adjusted for multiple clinicopathologic and treatment variables.

Results

The study included 244,794 patients: 25,546 (10%) with mucinous, 2,260 (1%) with signet ring, and 216,988 (89%) with nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinoma. Mucinous and signet ring cancers were more frequently right-sided (60% and 62%, respectively) than were nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas (42%, P < .001). Signet ring histology was associated with a higher stage (P < .001), and 77.2% of signet ring tumors were high-grade lesions, compared with 20% of mucinous and 17% of non–signet ring, nonmucinous adenocarcinomas (P < .001). After adjustment for covariates, signet ring histology was independently associated with higher risk of death (HR 1.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.33-1.51, and HR 1.57, CI 1.38-1.77, for tumors located in the colon and rectum, respectively). Mucinous tumors of the rectum (HR 1.22, CI 1.16-1.29), but not the colon (HR 1.03, CI 1.00-1.06), were associated with increased risk of death.

Conclusion

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas of the colon and rectum and mucinous adenocarcinomas of the rectum are associated with poorer survival. These aggressive histologic variants of colorectal adenocarcinoma should be targeted for research initiatives to improve outcomes.

Introduction

Adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum is a major source of cancer-related mortality in the United States and was projected to account for approximately 51,370 deaths in the United States in 2010 [1]. While adenocarcinomas are the most common tumors of the colon and rectum, variant histologic subtypes have been reported to be associated with varied survival outcomes. Commonly studied subtypes of colorectal adenocarcinoma include mucinous and signet ring cell histologies, which represent approximately 5–15% and 1%, respectively [2].

Both histologies are differentiated from standard adenocarcinoma by levels of mucin within the tumor. Signet ring cell carcinomas are characterized by intracytoplasmic mucin that displaces the nucleus [3, 4]. Mucinous tumors are defined as being composed of >50% extracellular mucin produced by tumor acinar cells [5, 6]. The importance of these distinct histologic appearances lies in the observed differences in clinical features and survival outcomes.

Signet ring cell histology has been uniformly associated with younger patient populations, later stage of presentation, and worse outcomes compared with non–signet ring adenocarcinomas [2, 3, 7-10]. This association has been made from several smaller single- and multi-institutional reports [3, 7-10] as well as population-based registry data[2], with stage-independent survival implied. Fewer data exist regarding mucinous histology, which has been associated with younger age at presentation and variable outcomes compared with other adenocarcinomas and is associated with the microsatellite instability pathway [2, 11-20].

Both histologies are relatively rare, and this contributes to the difficulty of examining clinicopathologic features as well as survival outcomes. It is also unclear whether these features and outcomes differ between primary tumor sites (colon vs. rectum). The purpose of this study was to address these questions using a large, hospital-based registry of cancer patients in the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). We hypothesized that signet ring cell and mucinous histologies would more frequently occur in younger patients and at more advanced stages compared with non–signet ring cell, non-mucinous carcinomas. We also hypothesized that signet ring cell tumors would be associated with lower 5-year relative survival, but because of higher association with the microsatellite instability pathway, mucinous histology may be associated with similar or higher 5-year relative survival.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

We analyzed data from the NCDB. The NCDB, a joint program of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society, serves as a registry of cancer patients at Commission on Cancer–accredited hospitals throughout the United States. Since 1989, the database has captured clinicopathologic, treatment, and outcome information for approximately 70% of the diagnosed cancers in the United States [21].

Population

We identified all patients aged 18–90 years in the NCDB registry with adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum according to their International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes (ICD-O-3: C180-8, C209) between the years of 1998 and 2002. Using the ICD-9-O 3rd edition coding schema, we then identified patients with the tumor histologic subtypes mucinous (8480, 8481), signet ring cell (8490) and non-mucinous, non-signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (8000, 8010, 8020, 8021, 8140, 8141, 8143, 8144, 8210, 8211, 8220, 8221, 8260, 8261, 8262, 8263).

Patient demographic, tumor, and treatment related characteristics were then evaluated based on comparing their tumor histology and location. Patient related factors included sex, race, age and year of diagnosis. Tumor characteristics included location, stage (AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition), and grade. For the purposes of this study, tumors were classified as “right colon” if they were found in the cecum, ascending colon, or transverse colon, and they were classified as “left colon” if they were in the descending or sigmoid colon. Well and moderately differentiated tumors were defined as low grade, whereas poorly or undifferentiated tumors were defined as high grade.

In addition to patient and tumor characteristics, patient treatment characteristics were also included in the analysis. We evaluated receipt of cancer-directed surgery, (partial colectomy, subtotal colectomy, total colectomy, or proctocolectomy), the inclusion of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and the sequence of radiotherapy in relation to chemotherapy.

Statistical Analysis

X2 tests were used to compare categorical baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by histologic subtype. Treatment differences were examined separately for colon and rectal tumors given the different treatment strategies for the two sites. Five-year relative survival was determined from the year of diagnosis by calculating the ratio of observed to expected survival rates of the similar sex- and age-matched U.S. population[22]. Population survival data were obtained from the Human Mortality Database, 1998–2007 (http://www.mortality.org, last accessed November 6, 2010). Relative survival analysis is an established method of performing survival studies that provides an objective measure of survival of cancer patients in the absence of other causes taking into account potential reporting errors in cause of death [22, 23]. It is defined as the ratio of observed survival (all causes of death) amongst a cohort of cancer patients to the expected survival of a comparable cohort of patients without cancer. We determined 5-year relative survival and 95% confidence intervals (CI) according to cancer stage for patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum separately given the different treatment strategies applied to these tumor locations. To assess the impact of histological type on relative survival while adjusting for potential covariate influences, we performed multivariate relative survival analysis using generalized linear models assuming Poisson distribution for the observed number of deaths [24]. Covariates adjusted in the regression model were based on their availability in the dataset and their significance in univariate analyses. Models were built separately for colon and rectum to account for the treatment difference in these two distinct cancer sites. All the reported P values were two-sided, and values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses in this report were performed using STATA 11 MP software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

A total of 244,794 cases of colorectal carcinoma were diagnosed between 1998 and 2002 and included for analysis (Table 1). The majority of patients (89%) were diagnosed with non–signet ring cell, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma. Signet ring histology was exceedingly rare (1.0%). The distribution of histology was similar in all patients with regard to race and sex, although mucinous tumors were found in more women (54%) than men, unlike the other histologies (P <0.0001). For both tumor sites combined, signet ring histology was identified with higher frequency in younger patients than were mucinous and nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas (19% vs. 10% and 10%, respectively, P<0.01), and this pattern was also seen when patients were stratified by site (Table 2). For all histologies, rectal cancer was more frequently diagnosed in men (Table 2). There was no temporal difference between histologies in terms of number of cases diagnosed per year.

Table 1. Clinicopatholigic features*.

| Non-SR, Non-M Adenocarcinoma | Signet-Ring | Mucinous | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Total Patients | 216,988 | 89% | 2,260 | 1% | 25,546 | 10% |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 109,993 | 51% | 1,129 | 50% | 13,881 | 54% |

| Male | 106,995 | 49% | 1,131 | 50% | 11,665 | 46% |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 187,912 | 87% | 1,987 | 88% | 22,363 | 88% |

| African-American | 20,867 | 10% | 190 | 8% | 2,320 | 9% |

| Other | 8,209 | 4% | 83 | 4% | 863 | 3% |

| Age of Diagnosis | ||||||

| 18-49 | 20,743 | 10% | 434 | 19% | 2,637 | 10% |

| 50-75 | 126,603 | 58% | 1,163 | 51% | 13,822 | 54% |

| 76-90 | 69,642 | 32% | 663 | 29% | 9,087 | 36% |

| Tumor Location | ||||||

| Right colon | 90,180 | 42% | 1,390 | 62% | 15,394 | 60% |

| Left colon | 68,075 | 31% | 422 | 19% | 5,643 | 22% |

| Rectum | 58,733 | 27% | 448 | 20% | 4,509 | 18% |

| Stage (AJCC 6th ed.) | ||||||

| I | 57,331 | 26% | 131 | 6% | 3,454 | 14% |

| IIA | 59,003 | 27% | 275 | 12% | 7,692 | 30% |

| IIB | 5,915 | 3% | 54 | 2% | 1,155 | 5% |

| IIIA | 8,338 | 4% | 37 | 2% | 788 | 3% |

| IIIB | 34,013 | 16% | 381 | 17% | 4,562 | 18% |

| IIIC | 19,672 | 9% | 720 | 32% | 3,357 | 13% |

| IV | 32,716 | 15% | 662 | 29% | 4,538 | 18% |

| Grade | ||||||

| Low | 169,789 | 78% | 197 | 9% | 17,695 | 69% |

| High | 37,458 | 17% | 1,737 | 77% | 5,104 | 20% |

| Unknown | 9,741 | 4% | 326 | 14% | 2,747 | 11% |

Data combined for both colon and rectal cancer patients

Table 2. Tumor Site-Specific Demographics.

| Colon Cancer | Rectal Cancer | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Non-SR*, non-M** Adenocarcinoma (n=158,255) | Signet Ring (n=1,812) | Mucinous (n=21,037) | Non-SR, non-M Adenocarcinoma (n=58,733) | Signet Ring (n=448) | Mucinous (n=4,509) | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Age Group | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 18-49 | 13,108 | 8% | 303 | 17% | 1,999 | 10% | 7,635 | 13% | 131 | 29% | 638 | 14% |

| 50-75 | 89,021 | 56% | 927 | 51% | 10,989 | 52% | 37,582 | 64% | 236 | 53% | 2,833 | 63% |

| 76-90 | 56,126 | 35% | 582 | 32% | 8,049 | 38% | 13,516 | 23% | 81 | 18% | 1,038 | 23% |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 84,264 | 53% | 955 | 53% | 11,891 | 57% | 25,729 | 44% | 174 | 39% | 1,990 | 44% |

| Male | 73,991 | 47% | 857 | 47% | 9,146 | 43% | 33,004 | 56% | 274 | 61% | 2,519 | 56% |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 135,762 | 86% | 1,597 | 88% | 18,401 | 87% | 52,150 | 89% | 390 | 87% | 3,962 | 88% |

| African | ||||||||||||

| American | 16,890 | 11% | 151 | 8% | 1,982 | 9% | 3,977 | 7% | 39 | 9% | 338 | 7% |

| Others | 5,603 | 4% | 64 | 4% | 654 | 3% | 2,606 | 4% | 19 | 4% | 209 | 5% |

| Tumor Location | ||||||||||||

| Right | 90,180 | 57% | 1,390 | 77% | 15,394 | 73% | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Left | 68,075 | 43% | 422 | 23% | 5,643 | 27% | ||||||

| AJCC Stage | ||||||||||||

| I | 38,372 | 24% | 108 | 6% | 2,778 | 13% | 18,959 | 32% | 23 | 5% | 676 | 15% |

| IIA | 45,614 | 29% | 237 | 13% | 6,642 | 32% | 13,389 | 23% | 38 | 8% | 1,050 | 23% |

| IIB | 4,819 | 3% | 45 | 2% | 974 | 5% | 1,096 | 2% | 9 | 2% | 181 | 4% |

| IIIA | 4,894 | 3% | 25 | 1% | 583 | 3% | 3,444 | 6% | 12 | 3% | 205 | 5% |

| IIIB | 25,441 | 16% | 315 | 17% | 3,730 | 18% | 8,572 | 15% | 66 | 15% | 832 | 18% |

| IIIC | 13,792 | 9% | 523 | 29% | 2,464 | 12% | 5,880 | 10% | 197 | 44% | 893 | 20% |

| IV | 25,323 | 16% | 559 | 31% | 3,866 | 18% | 7,393 | 13% | 103 | 23% | 672 | 15% |

| Tumor Grade | ||||||||||||

| Low | 122,454 | 77% | 160 | 9% | 14,707 | 70% | 47,335 | 81% | 37 | 8% | 2,988 | 66% |

| High | 29,322 | 19% | 1,402 | 77% | 4,207 | 20% | 8,136 | 14% | 335 | 75% | 897 | 20% |

| Unknown | 6,479 | 4% | 250 | 14% | 2,123 | 10% | 3,262 | 6% | 76 | 17% | 624 | 14% |

=Signet ring;

=Mucinous

The distribution of sites for primary tumors was similar for nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas (Table 1). However, the majority of signet ring and mucinous tumors were found in the right colon (62% and 60%, respectively, P<0.01). Approximately half of all nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas were diagnosed early (stage I or II), whereas 80% of signet ring cancers were diagnosed at later stages (III or IV, P<0.01). As opposed to mucinous or nonmucinous non–signet adenocarcinomas, most signet ring tumors were high-grade lesions (77%, P<0.01).

Treatment Characteristics

Regardless of histology or tumor location, 92–98% of all patients examined received cancer-directed surgery (Table 3). Chemotherapy was administered to a higher percentage of patients with signet ring or mucinous tumors than patients with nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas (P <0 .001). Among patients with rectal cancer, those with signet ring or mucinous histology were more likely to undergo radiotherapy than were those with nonmucinous, non–signet ring tumors (P < 0.001). It should be noted that there is a higher proportion of mucinous and signet ring histology patients with advanced stage disease, which may account for these differences in chemotherapy delivery vs. patients with nonmucinous, non-signet ring tumors.

Table 3. Treatment Characteristics.

| Colon | Rectum | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Non-SR, Non-M Adenocarcinoma | Signet-Ring | Mucinous | Non-SR, Non-M Adenocarcinoma | Signet-Ring | Mucinous | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Cancer Directed Surgery | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Yes | 155,809 | 98% | 1,745 | 96% | 20,745 | 99% | 56,975 | 97% | 412 | 92% | 4,388 | 97% |

| No | 2,446 | 2% | 67 | 4% | 292 | 1% | 1,758 | 3% | 36 | 8% | 121 | 3% |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yes | 54,832 | 35% | 965 | 53% | 8,508 | 40% | 29,678 | 51% | 325 | 73% | 2,895 | 64% |

| No | 103,423 | 65% | 847 | 47% | 12,529 | 60% | 29,055 | 49% | 123 | 27% | 1,614 | 36% |

| Radiation | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24,042 | 41% | 283 | 63% | 2,416 | 54% | |||

| No | N/A | N/A | N/A | 34,691 | 59% | 165 | 37% | 2,093 | 46% | |||

Survival Analysis

Five-year relative survival was determined and stratified by histology, stage, and tumor location (Table 4). Median follow up time was 66.8 months (interquartile range: 60.2-72.1 months). For both colon and rectal cancers and all histologies, relative survival decreased with increasing stage, with the exception that patients with stage IIIA cancer had higher relative survival than patients with stage II cancer. Signet ring histology was associated with lower relative survival, stage-for-stage, than either mucinous or nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas for both tumor sites. Among patients with tumors in the colon, relative survival for those with mucinous cancers was not different than that for patients with nonmucinous, non–signet adenocarcinomas. However, among patients with rectal cancer, mucinous cancers were associated with lower relative survival than were nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas.

Table 4. Five Year Relative Survival and 95% Confidence Interval.

| Colon | Rectum | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| AJCC 6th stage | Nonmucinous, non-signet ring Adenocarcinoma | Signet ring | Mucinous | Nonmucinous, non-signet Adenocarcinoma | Signet ring | Mucinous | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| I | 0.94 | .94-.95 | 0.87 | .74-.98 | 0.92 | .90-.94 | 0.92 | .91-.93 | 0.61 | .35-.81 | 0.92 | .88-.95 |

| IIA | 0.84 | .83-.84 | 0.81 | .73-.89 | 0.84 | .83-.86 | 0.79 | .78-.80 | 0.52 | .33-.70 | 0.73 | .70-.77 |

| IIB | 0.61 | .59-.63 | 0.54 | .35-.72 | 0.64 | .60-.68 | 0.55 | .51-.58 | 0.38 | .08-.75 | 0.5 | .41-.59 |

| IIIA | 0.86 | .85-.88 | 0.81 | .54-.99 | 0.87 | .82-.92 | 0.86 | .84-.87 | 0.91 | .49-1.11 | 0.82 | .74-.89 |

| IIIB | 0.65 | .64-.66 | 0.49 | .42-.56 | 0.66 | .64-.68 | 0.64 | .62-.65 | 0.55 | .40-.68 | 0.56 | .52-.60 |

| IIIC | 0.45 | .44-.46 | 0.21 | .17-.25 | 0.42 | .40-.45 | 0.48 | .47-.50 | 0.3 | .23-.37 | 0.44 | .40-.47 |

| IV | 0.08 | .08-.09 | 0.02 | .01-.04 | 0.08 | .07-.09 | 0.11 | .10-.11 | 0.05 | .02-.11 | 0.07 | .05-.09 |

Multivariate Adjusted Survival Analysis

After adjusting for tumor stage, year of diagnosis, and surgery, we performed a multivariate adjusted relative survival analysis stratified by tumor location (Table 5). For patients with either colon or rectal tumors, signet ring histology was associated with a 42-57% higher risk of death compared to nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas (HR 1.42, CI 1.33-1.51, and HR 1.57, CI 1.38-1.77, for tumors of the colon and rectum, respectively). There was a very small but statistically significant increased risk of death associated with mucinous tumors of the colon compared with other histologies (HR 1.03, CI 1.00-1.06). However, among patients with rectal carcinomas, mucinous histology was independently associated with a 22% increased relative risk of death compared with nonmucinous adenocarcinomas (HR 1.22, CI 1.16-1.29).

Table 5. Relative Survival Regression Analysis*.

| Variable | Colon | Rectum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma** | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Signet ring | 1.42 | 1.33-1.51 | 1.57 | 1.38-1.77 |

| Mucinous | 1.03 | 1.00-1.06 | 1.22 | 1.16-1.29 |

| Age | ||||

| 18-49 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| 50-75 | 1.14 | 1.10-1.17 | 1.14 | 1.08-1.19 |

| 76-90 | 1.55 | 1.50-1.61 | 1.66 | 1.56-1.75 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Male | 1.03 | 1.01-1.05 | 1.04 | 1.00-1.07 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Afr. American | 1.23 | 1.20-1.26 | 1.31 | 1.24-13.39 |

| Other | 0.82 | 0.77-0.86 | 0.86 | 0.79-0.93 |

| Grade | ||||

| Low | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| High | 1.57 | 1.53-1.60 | 1.50 | 1.45-1.56 |

| Unknown | 1.15 | 1.10-1.20 | 1.09 | 1.01-1.16 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| no | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| yes | 0.51 | 0.50-0.52 | 0.61 | 0.58-0.64 |

| Radiation | ||||

| no | - | - | 1 | - |

| yes | - | - | 0.87 | 0.83-0.90 |

| Cancer Directed Surgery | ||||

| no | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| yes | 0.45 | 0.43-0.47 | 0.49 | 0.46-0.52 |

Also adjusted for tumor stage and year of diagnosis

Non-signet ring, non-mucinous

Our multivariate adjusted relative survival analysis results mirror overall survival multivariate adjusted analysis, with signet ring histology associated with worse survival for both colon (HR 1.31; CI 1.24-1.39) and rectal (HR 1.5; CI 1.34-1.68) tumors compared to nonmucinous, non-signet ring tumors. Similarly to the multivariate adjusted relative survival analysis, mucinous tumors of the colon had a small, but statistically significant increased risk of death in overall survival analysis (HR 1.04; CI 1.02-1.06) compared to nonmucinous, non-signet ring adenocarcinomas. Lastly, rectal mucinous tumors were independently associated with a higher risk of death via overall survival analysis when compared to nonmucinous, non-signet ring histology (HR 1.18; 95% CI 1.13-1.23).

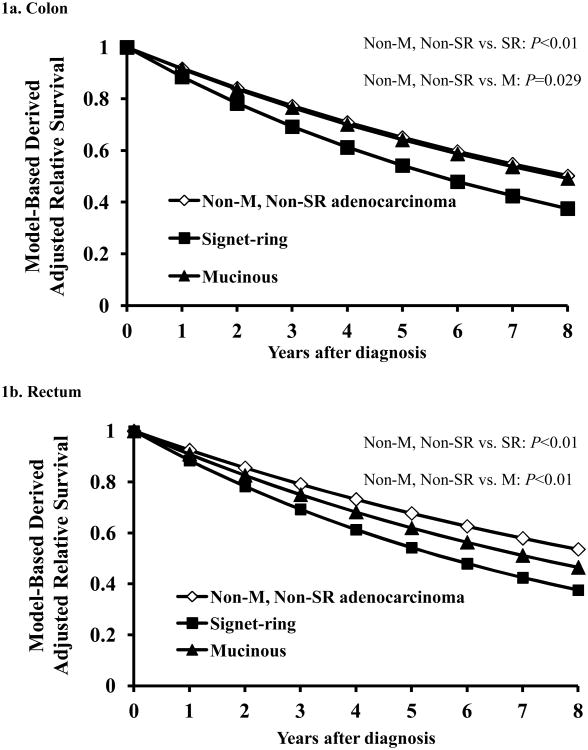

To further illustrate the effect of multiple simultaneous variables on relative survival, we utilized the adjusted model to plot relative survival curves by histology for patients with tumors of the colon or rectum for years one through five post-resection (Figure 1). The adjusted relative survival curves demonstrate the poorer outcomes associated with signet ring histology compared with both mucinous and nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas in either the colon or the rectum. The curves also highlight the increased risk of death associated with mucinous histology compared with nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas for patients with tumors in the rectum but not for patients with tumors in the colon.

Figure 1.

Model based estimates of relative survival stratified by tumor histology for the colon (1a) and rectum (1b). In both the colon and rectum, signet ring cell carcinomas had worse relative survival compared to both mucinous and nonmucinous, non-signet ring adenocarcinomas. Mucinous histology was associated with worse relative survival compared to nonmucinous, non-signet ring adenocarcinoma in the rectum only. Abbreviations: Non-M = Nonmucinous Non-SR = Non-signet ring

After adjustment, gender was not associated with a clinically meaningful impact on relative survival for patients with tumors of the colon or rectum. However, African-American race was independently associated with increased risk of death for patients with colon or rectal cancers compared with white and other races. High-grade lesions, regardless of tumor site, were associated with worse outcomes for patients compared with lesions of low or unknown grade. The receipt of chemotherapy and radiotherapy were independently associated with higher relative survival compared with not receiving those therapies (Table 5).

Discussion

Our analysis identified unique clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes associated with signet ring cell and mucinous colorectal adenocarcinomas as well as site-specific differences in long-term outcomes using the National Cancer Data Base. Our hypothesis that signet ring cell and mucinous histologies would more frequently occur in younger patients and at more advanced stages compared with non–signet ring cell, nonmucinous carcinomas was confirmed, as was our hypothesis that signet ring cell tumors would be associated with lower 5-year relative survival. However, we did not find mucinous histology to be associated with higher 5-year relative survival compared with nonmucinous histology.

Signet ring tumors accounted for less than 1% of all reported adenocarcinomas and were more likely to present at a younger age than were non–signet ring adenocarcinomas. Signet ring histology was also associated with a higher grade and more advanced stage at presentation. After adjusting for tumor stage, year of diagnosis, and receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, signet ring histology was independently associated with poorer outcomes compared with other subtypes of adenocarcinoma regardless of tumor location (Table 5). These data reflect the aggressive behavior of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas.

Mucinous tumors were diagnosed 10 times more often than signet ring cell lesions, but they were still much less common than nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas. Mucinous tumors shared many clinicopathologic features with signet carcinomas, including younger age at presentation and more frequent proximal (right colon) location. The higher incidence of stage III and IV disease at presentation suggests most mucinous tumors were probably not associated with the microsatellite instability pathway. Furthermore, despite its historical association with the microsatellite instability pathway and therefore potentially improved outcomes, mucinous histology was not a stage-independent factor affecting survival for patients with colon cancer. After adjusting for tumor stage and year of diagnosis, there was no clinically significant difference in relative survival between mucinous tumors and nonmucinous, non–signet ring adenocarcinomas of the colon (HR 1.03, CI 1.00-1.06) (Table 5). Interestingly, we observed that a high relative risk of death was independently associated with mucinous tumors of the rectum (HR 1.22, CI 1.16-1.29). While our analysis cannot provide insight into a mechanism for this observed difference, it has been reported that mucinous tumors of the rectum may be less likely to respond to neoadjuvant chemoradiation and are linked to poorer disease-specific survival compared with nonmucinous adenocarcinomas[25]. In light of the evidence regarding the associations between pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation and survival, our data appear to confirm this observation.

Our analysis has a number of strengths and weaknesses. The NCDB registry covers approximately 70% of all cancer diagnoses in the United States, but there may be underrepresentation of some minorities, such as Hispanics and Asian-Americans. Despite this limitation, the NCDB does allow study of relatively rare pathologies such as is presented in our study, which is the largest to date in the literature. Our study benefits from the large number of reported patients to provide broad insight into the clinicopathologic features and outcomes among these patients. Although specific information regarding disease recurrence was not available, we did perform multivariate adjusted relative survival analysis to estimate the cancer-related mortality while accounting for potential bias from death from other causes or from errors in coding of death certificates about exact cause of death. Relative survival analysis attempts to correct for those biases which are more likely present when using overall survival models for analysis. In spite of having such a large cohort of colorectal cancer patients to facilitate study of less common tumor types, some of the sub-cohorts within the NCDB are still relatively small, a point that should be considered during subgroup comparisons. However, for the entire cohort, our findings with respect to stage-associated relative survival are consistent with the univariate observed relative survival within SEER (e.g. improved survival of stage IIIA patients when compared to stage II) used to validate the changes from the AJCC 6th to the 7th editions[26].

Also, this study relies on pathologic review and histologic classification of adenocarcinoma as reported by a variety of independent pathologists. While definitions of mucinous and signet ring cell histologies have been standardized, variations in interpretation may exist, resulting in misclassification bias for which we cannot account. However, signet ring cells and mucin-producing tumors have relatively distinct features; therefore, this is not likely to represent a significant threat to the analysis. Although the presence of acellular mucin without viable cancer cells among patients with rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant radiation or chemoradiation has not been associated with adverse outcomes [27, 28], it is possible that pools of mucin in nonmucinous tumors may have been misinterpreted as mucinous adenocarcinomas. However, acellular mucin is associated with response to neoadjuvant therapy, and therefore this misclassification would have resulted in a decrease in the magnitude of the observed effects. In addition, data regarding microsatellite instability testing are not captured within the NCDB registry, and therefore the impact of this information was not included in our analysis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the association between signet ring cell tumors and stage-independent poorer outcomes compared with non–signet ring adenocarcinomas of either the colon or rectum. Mucinous adenocarcinomas are independently associated with poorer outcomes for rectal but not colon cancer patients. These findings mandate routine reporting of these variants in surgical pathologic specimens, and efforts to include them in preoperative biopsies should be made. Counseling of patients may be affected by the knowledge of poorer stage-related outcomes with these histologic subtypes. This information may also be considered to target patients for novel clinical trials development and explore treatment strategies to improve their outcome.

Synopsis.

Utilizing the National Cancer Data Base, we examined the site-specific clinicopathologic features and relative survival outcomes of the signet ring and mucinous variants of colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Institute for Cancer Care Excellence at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for additional support of this work.

Source of Funding: Supported by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Foundation Career Development Award (G.J.C.) and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grants K07-CA133187 (G.J.C.) and CA016672 (MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant).

Footnotes

Disclosure: We have no commercial interest in the subject of the study and have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang H, O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, et al. A 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1161–1168. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0932-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borger ME, Gosens MJ, Jeuken JW, et al. Signet ring cell differentiation in mucinous colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2007;212:278–286. doi: 10.1002/path.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messerini L, Palomba A, Zampi G. Primary signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1995;38:1189–1192. doi: 10.1007/BF02048335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Symonds DA, Vickery AL. Mucinous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1976;37:1891–1900. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197604)37:4<1891::aid-cncr2820370439>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parham D. Colloid Carcinoma. Annals of surgery. 1923;77:90–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizushima T, Nomura M, Fujii M, et al. Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival. Surg Today. 40:234–238. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pande R, Sunga A, Levea C, et al. Significance of signet-ring cells in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song W, Wu SJ, He YL, et al. Clinicopathologic features and survival of patients with colorectal mucinous, signet-ring cell or non-mucinous adenocarcinoma: experience at an institution in southern China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1486–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung CO, Seo JW, Kim KM, et al. Clinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1533–1541. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg JW, Godwin JD., 2nd The epidemiologic pathology of carcinomas of the large bowel. J Surg Oncol. 1974;6:381–400. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930060503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2073–2087 e2073. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connelly JH, Robey-Cafferty SS, Cleary KR. Mucinous carcinomas of the colon and rectum. An analysis of 62 stage B and C lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consorti F, Lorenzotti A, Midiri G, Di Paola M. Prognostic significance of mucinous carcinoma of colon and rectum: a prospective case-control study. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73:70–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(200002)73:2<70::aid-jso3>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green JB, Timmcke AE, Mitchell WT, et al. Mucinous carcinoma--just another colon cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:49–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanemitsu Y, Kato T, Hirai T, et al. Survival after curative resection for mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colorectum. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2003;46:160–167. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nozoe T, Anai H, Nasu S, Sugimachi K. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. J Surg Oncol. 2000;75:103–107. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200010)75:2<103::aid-jso6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purdie CA, Piris J. Histopathological grade, mucinous differentiation and DNA ploidy in relation to prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki O, Atkin WS, Jass JR. Mucinous carcinoma of the rectum. Histopathology. 1987;11:259–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb02631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie L, Villeneuve PJ, Shaw A. Survival of patients diagnosed with either colorectal mucinous or non-mucinous adenocarcinoma: a population-based study in Canada. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1109–1115. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ederer F, Axtell LM, Cutler SJ. The relative survival rate: a statistical methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1961;6:101–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoel DG, Ron E, Carter R, Mabuchi K. Influence of death certificate errors on cancer mortality trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1063–1068. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.13.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23:51–64. doi: 10.1002/sim.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin US, Yu CS, Kim JH, et al. Mucinous rectal cancer: effectiveness of preoperative chemoradiotherapy and prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2232–2239. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Revised TN categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:264–271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shia J, Guillem JG, Moore HG, et al. Patterns of morphologic alteration in residual rectal carcinoma following preoperative chemoradiation and their association with long-term outcome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:215–223. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KD, Tan D, Das P, et al. Clinical significance of acellular mucin in rectal adenocarcinoma patients with a pathologic complete response to preoperative chemoradiation. Ann Surg. 251:261–264. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bdfc27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]