Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Vitamin E suppresses the development of atherosclerosis but does not regress established hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

OBJECTIVES:

To investigate whether vitamin E slows the progression of established atherosclerosis, and whether this effect is associated with reductions in serum lipids and oxidative stress.

METHODS:

The present study was performed in four groups of rabbits: group I, regular diet (control); group II, 0.25% cholesterol diet (two months); group III, 0.25% cholesterol diet (four months); and group IV, 0.25% cholesterol diet (two months) followed by 0.25% cholesterol and vitamin E (two months). Serum lipids and the chemiluminescent activity of white blood cells (WBC-CL), a measure of oxygen radical production by white blood cells, were measured before and at monthly intervals for the duration of the study. Aortas were removed at the end of the protocol for assessment of atherosclerosis and the chemiluminescent activity of aortic tissue (aortic-CL), a measure of antioxidant reserve.

RESULTS:

Atherosclerosis was associated with hyperlipidemia and increased oxidative stress, indicated by increased nonactivated WBC-CL and alteration of the aortic-CL. Significant areas of the intimal surfaces of the aortas from group II (26.54%±4.11%), group III (69.37%±5.34%) and group IV (65.96%±7.86%) were covered with atherosclerotic lesions. Vitamin E did not alter serum lipids, aortic antioxidant reserve or WBC-CL. Vitamin E was ineffective in slowing the progression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

CONCLUSION:

Vitamin E did not slow the progression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis, and this effect was associated with its ineffectiveness in reducing serum lipids and oxidative stress.

Keywords: Aortic antioxidant reserve, Atherosclerosis, Hypercholesterolemia, Slowing of progression of atherosclerosis, White blood cell chemiluminescence

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been implicated in the pathophysiology of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis (1–4). Antioxidants have been reported to suppress development of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis (1,2,4,5). Epidemiological studies indicate an inverse relationship between vitamin E intake and cardiovascular disease (6). Increased vitamin E intake is associated with a lower risk of coronary artery disease (7,8). However, several clinical trials have shown conflicting results. In some studies (9–11), vitamin E treatment significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death and nonfatal myocardial infarction. However, several other studies have shown neither harm nor benefit of vitamin E therapy in patients with established ischemic heart disease (12–15). Reports of the effects of vitamin E on the progression of atherosclerosis are conflicting. Hodis et al (16) reported that vitamin E supplementation in healthy individuals did not reduce the progression of intima-media thickness over a three-year period. However, Cyrus et al (17) reported that vitamin E supplementation reduces progression of established atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-deficient mice. Averill et al (18) showed that vitamin E does not inhibit the progression of established atherosclerotic lesions in old apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. The controversial effects of vitamin E in established coronary artery disease may be due to endogenous antioxidant status among the participants, timing of intervention relative to the atherosclerotic process, its ineffectiveness in regression or slowing of progression of atherosclerosis in established coronary artery disease, end points (mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction, selected for effectiveness of vitamin E), administration of vitamin E with other drugs, and the type of vitamin E. Vitamin E has been reported to suppress hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis (1) but it does not produce regression of atherosclerosis (19). It is not known whether vitamin E would be effective in slowing the progression of established atherosclerosis. The objectives of the present study were to determine whether vitamin E slows the progression of already developed atherosclerosis, and whether slowing the progression of atherosclerosis is associated with reductions in serum lipids and oxidative stress. An investigation of the effects of vitamin E on the progression of pre-existing atherosclerosis in rabbits on a high-cholesterol diet was therefore performed. Serum lipids (triglycerides [TG], total cholesterol [TC], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], LDL cholesterol [LDL-C] and the cholesterol risk ratio [TC/HDL-C]), oxidative stress (aortic antioxidant reserve, measured as aortic chemiluminescence [aortic-CL], and the ROS-producing activity of white blood cells [WBCs], measured as the chemiluminescent activity of WBCs [WBC-CL]) and atherosclerotic changes in the aorta were measured to achieve the above objectives.

METHODS

New Zealand White female rabbits weighing between 1.2 kg and 1.5 kg were assigned to one of four groups after one week of adaptation on a regular rabbit chow diet (Table 1). The 0.25% cholesterol diet with or without vitamin E was prepared by LabDiet (PMI Nutrition International, USA). The rabbits were housed in individual cages at 20°C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. The experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan), and the animal care adhered to approved standards of laboratory animal care. The rabbits were on their respective diets for the specified duration. Fasting blood samples (from the ear marginal artery) were collected before (month 0) and at monthly intervals for the measurement of serum lipids and WBC-CL. At the end of the protocol, the rabbits were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg intravenously) and the aortas were removed for assessment of atherosclerotic lesions and aortic-CL.

TABLE 1.

Experimental diet group

| Group | Diet/treatment |

|---|---|

| I (n=6) | Control (regular laboratory rabbit chow diet) for 2 months |

| II (n=6) | 0.25% cholesterol diet for 2 months* |

| III (n=6) | 0.25% cholesterol diet for 4 months |

| IV (n=6) | 0.25% cholesterol diet for 2 months followed by 0.25% cholesterol diet plus vitamin E (40 mg/kg body weight orally daily for an additional 2 months) |

The 0.25% cholesterol diet for 2 months represents a 0.25% cholesterol diet for 2 months in each group except that the diet in the fourth week contained 1% cholesterol

Serum lipids

TG, TC and HDL-C were measured on an automated Beckman Synchron LX20 Clinical System Analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc, USA). The values of LDL-C were calculated automatically by the analyzer. The cholesterol risk ratio was estimated using the quotient of TC/HDL-C.

Aortic-CL

Aortas between the origin and bifurcation to the iliac arteries were removed under anesthesia, cleaned of gross adventitial tissue and cut longitudinally into two halves. One half was used for measurement of atherosclerotic changes, and the other half was used to prepare a supernatant by a previously described method (2) for measurement of aortic-CL. Aortic-CL was measured by a previously described method (2,20). Increases in the aortic-CL indicate a decrease in the antioxidant reserve and vice versa. Briefly, 0.4 mL of aortic supernatant was added to a tube containing 0.2 mL of 2×10−4 M luminol, placed in a luminometer (Autolumat LB953; EG&G Berthold, Germany) at 37°C and incubated for 5 min. The reaction was started by adding 0.1 mL of 200 mmol/L tert-butyl hydroperoxide. The chemiluminescence was read for a period of 6 s continuously for 10 min. The chemiluminescence unit was the relative light unit (RLU). The aortic-CL was expressed as RLU/mg protein.

WBC-CL

Arterial blood collected in EDTA-containing tubes was used to measure WBC counts using a CELL-DYN 4000 automated analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, USA). Measurements of WBC-CL were made using a previously described method (1,21). In short, 0.05 mL of blood was added to a tube containing Hank’s balanced salt solution and luminol at a final concentration of 10−4 M. Samples were placed in a luminometer (Autolumat LB953) at 37°C, and phagocytosis was started by adding 0.1 mL (10 mg/mL stock solution) of opsonized zymosan prepared as previously described (1). The final volume of the mixture was 0.5 mL. The chemiluminescence was monitored for 3 s every 2 min for a period of 60 min. The area under the curve was integrated to arrive at the total chemiluminescent activity. The difference between the total chemiluminescent activity of the zymosan-activated and nonzymosan-activated chemiluminescent activity was designated as the total WBC-derived ROS. The chemiluminescent activity unit was the RLU. The chemiluminescent activity of the WBCs is expressed as RLU/WBC. Nonactivated and zymosan-activated WBC-CL were reported.

Assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta

Assessment of atherosclerotic changes in the aorta was performed by using Herxheimer’s solution containing Sudan IV for lipid staining (1,22). Photographs of the stained intimal surfaces of the aortas were taken using a digital camera. The digitized images were converted to TIFF file format using the software package Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems Inc, USA). The total and atherosclerotic areas of the intimal surfaces of the aortas were measured in pixels and square inches using NIH Image 1.62 (a public domain software package). The extent of atherosclerotic lesions was expressed as a percentage of the total intimal surface area.

Protein measurement

Protein content of the aortic supernatants was measured using the Biuret method (23).

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SE. Repeated measure of ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of serum lipids and WBC-CL. The unpaired Student’s ttest was used to analyze the aortic-CL data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine the differences in the atherosclerotic changes in the four groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the significance of differences between any two groups. Type 1 error for multiple comparisons was controlled by the Bonferroni correction. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Serum lipids

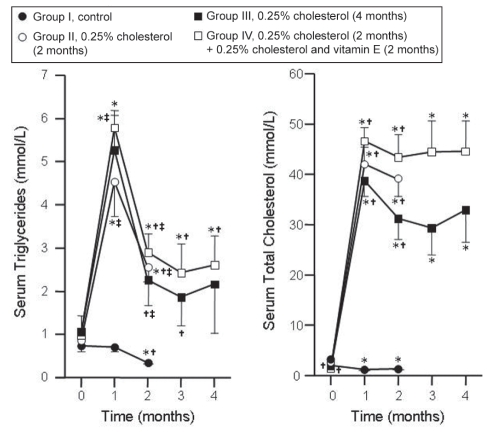

Initial concentrations of serum TG in groups I, II, III and IV were 0.73±0.14 mmol/L, 0.87±0.15 mmol/L, 1.03±0.10 mmol/L and 1.03±0.03 mmol/L, respectively, and were not significantly different from each other. The changes in the serum TG of the four groups are summarized in Figure 1. Serum levels of TG decreased in group I at month 2, while the levels increased in group II at months 1 and 2, group III at month 1 and group IV throughout compared with month 0. The levels were higher in groups II, III and IV at months 1 and 2 compared with group I. The values were similar in groups III and IV at months 3 and 4.

Figure 1).

Sequential changes in the serum triglycerides and total cholesterol of the four experimental groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. *P<0.05, month 0 versus other months in the respective groups; †P<0.05, month 1 versus other months in the respective groups; ‡P<0.05, group I versus other groups

The basal levels of serum TC were 2.04±0.23 mmol/L, 1.57±0.27 mmol/L, 1.39±0.17 mmol/L and 1.33±0.08 mmol/L, respectively, in groups I, II, III and IV. The values were higher in groups II and III compared with group I. The changes in the serum levels of TC in the four groups are summarized in Figure 1. The levels decreased in group I but increased in all other groups compared with month 0. The levels were higher in all groups compared with group I. There were no significant differences in the levels of serum TC between groups III and IV at all times. Vitamin E did not affect the serum levels of TC in rabbits with pre-existing hypercholesterolemia.

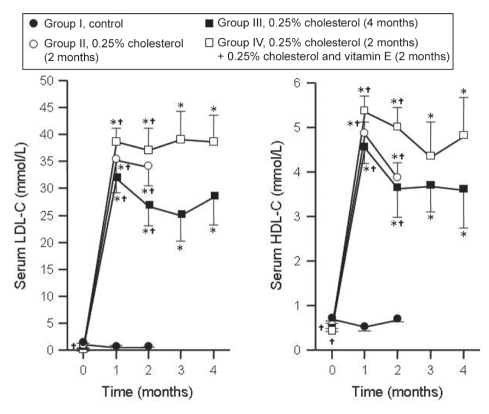

The initial levels of serum LDL-C in groups I, II, III and IV were 1.02±0.26 mmol/L, 0.64±0.23 mmol/L, 0.46±0.14 mmol/L and 0.39±0.09 mmol/L, respectively. The initial levels in group IV were lower than those in group I. The changes in serum levels of LDL-C are summarized in Figure 2. The levels remained unaltered in group I but increased in all other groups compared with month 0. The levels at months 1 and 2 were similar in groups II, III and IV but higher than those in group I. The levels of LDL-C at months 3 and 4 were not different between group III and group IV, suggesting that vitamin E does not affect LDL-C levels in rabbits with pre-existing hypercholesterolemia.

Figure 2).

Changes in the levels of serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) of the four experimental groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. *P<0.05, month 0 versus other months in the respective groups; †P<0.05, month 1 versus other months in the respective groups

The initial values of serum HDL-C were 0.69±0.03 mmol/L, 0.54±0.07 mmol/L, 0.47±0.06 mmol/L and 0.47±0.02 mmol/L in groups I, II, III and IV, respectively. The initial values in groups III and IV were lower than those in group I. The sequential changes in the serum levels of HDL-C in the four groups are summarized in Figure 2. The levels in group I remained unaltered, but increased in all other groups compared with month 0. The values were similar in groups II, III and IV, but higher than group I at months 1 and 2. The levels of serum HDL-C in groups III and IV were similar throughout, suggesting that vitamin E does not alter HDL-C levels in rabbits with pre-existing hypercholesterolemia.

The basal levels of the risk ratio TC/HDL-C in groups I, II, III and IV were 3.0±0.3, 2.9±0.2, 3.1±0.3 and 2.8±0.2, respectively, and they were not significantly different from each other. The sequential changes in the TC/HDL-C ratio are summarized in Table 2. The levels were lower in group I at month 2 compared with month 0, but were higher in all other groups compared with month 0 in the respective groups. The levels in groups III and IV at months 3 and 4 were similar to those at month 2, except in group IV, in which the levels were higher at month 3 compared with month 2. The data suggest that vitamin E did not affect the cholesterol risk ratio in rabbits with pre-existing hypercholesterolemia.

TABLE 2.

Changes in the cholesterol risk ratio (serum total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) in the four experimental groups

| Group |

Time, months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| I | 3.0±0.3 | 2.3±0.3 | 2.0±0.1* | ||

| II | 2.9±0.2 | 8.7±0.3*† | 10.2±0.3*†‡ | ||

| III | 3.1±0.3 | 8.6±0.4*† | 8.6±0.4*†§ | 7.9±0.5* | 9.4±0.4* |

| IV | 2.8±0.2 | 8.8±0.6*† | 8.7±0.4*†§ | 10.6±0.7***†† | 9.8±0.9* |

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Group I, control; Group II, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months); Group III, 0.25% cholesterol (4 months); and group IV, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months) plus 0.25% cholesterol and vitamin E (2 months).

P<0.05, month 0 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, month 1 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, month 2 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, month 3 versus month 4 in the respective groups;

P<0.05, group I versus other groups;

P<0.05, group II versus other groups;

P<0.05, group III versus group IV

WBC-CL

The sequential changes in the nonactivated and activated WBC-CL of the four groups are summarized in Table 3. Nonactivated WBC-CL is the activity without activation of the WBCs with zymosan, while activated WBC-CL is the activity with stimulation of WBCs using zymosan. The initial values of the nonactivated WBC-CL in groups I and II were similar while those in groups III and IV were lower compared with groups I and II. The values remained unchanged in group I but were higher in all other groups compared with month 0. The values at months 3 and 4 in groups III and IV were similar. These data suggest that hypercholesterolemia increases the generation of oxygen radicals by nonactivated WBCs, and that vitamin E does not affect the generation of oxygen radicals by nonactivated WBCs.

TABLE 3.

Changes in the chemiluminescent activity of nonactivated and zymosan-activated white blood cells (WBC-CL) in the four experimental groups

| Group |

Time, months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

Nonactivated WBC-CL, RLU/WBC | |||||

| I | 0.37±0.02 | 0.41±0.03 | 0.38±0.04 | ||

| II | 0.51±0.09 | – | 0.65±0.05* | ||

| III | 0.23±0.01*† | 0.50±0.11‡ | 0.38±0.04†‡ | 0.46±0.05‡ | 0.66±0.17‡ |

| IV | 0.25±0.03*† | 0.47± 0.02‡ | 0.78±0.04*‡§¶ | 0.38±0.05‡** | 0.51±0.11‡ |

|

Zymosan-activated WBC-CL, RLU/WBC | |||||

| I | 4.1±0.3 | 5.7±0.5‡ | 5.6±0.8 | ||

| II | 5.7±0.8 | – | 3.6±0.2*‡ | ||

| III | 5.0±0.9 | 5.1±0.9 | 2.5±0.3*†‡§ | 3.0±0.5 | 3.7±0.7 |

| IV | 5.7±1.6 | 5.2±0.7 | 5.1±0.6†¶ | 6.0±0.7¶ | 7.3±0.8**¶ |

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Group I, control; Group II, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months); Group III, 0.25% cholesterol (4 months); and group IV, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months) plus 0.25% cholesterol and vitamin E (2 months). RLU Relative light unit; WBC White blood cell.

P<0.05, month 0 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, month 1 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, month 2 versus other months in the respective groups;

P<0.05, group I versus other groups;

P<0.05, group II versus other groups;

P<0.05, group III versus group IV

The initial values of zymosan-activated WBC-CL were similar in all groups. The values in group I were higher at month 1 compared with month 0, but they were lower in groups II and III at month 2 compared with month 0 in the respective groups. The values in group IV at months 2, 3 and 4 were higher than those in group III. These data suggest that the generation of oxygen radicals by activated WBCs is reduced in hypercholesterolemic rabbits, and that vitamin E does not reduce the generation of oxygen radicals by activated WBCs.

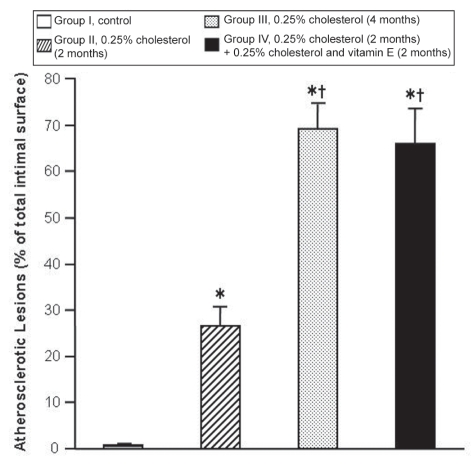

Atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta

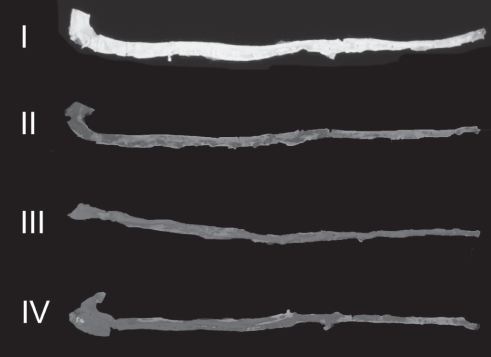

A representative photograph of atherosclerotic changes in the intimal surfaces of aortas from the four groups stained with Sudan IV is shown in Figure 3, and the extent of atherosclerotic lesions in these groups is summarized in Figure 4. There were no atherosclerotic lesions in the aortas of group I. However, significant areas of the intimal surfaces of aortas from group II (26.54%±4.11%), group III (69.37%±5.34%) and group IV (65.96%±7.86%) were covered with atherosclerotic plaques. The extent of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortas of rabbits in group III was 163% greater than in group II, suggesting that the atherosclerotic process progresses with time in the presence of hypercholesterolemia. The extent of atherosclerotic lesions in group IV was 149% greater than in group II. The extent of atherosclerosis in groups III and IV was similar, suggesting that vitamin E did not slow the progression of atherosclerosis.

Figure 3).

Representative photographs of the intimal surfaces of aortas of the four groups stained with Sudan IV. The lipid deposits on the intimal surfaces of the aortas are brick red in colour. Lipid deposits are absent on the intimal surface of the aorta from group I. I, control; II, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months); III, 0.25% cholesterol (4 months); and IV, 0.25% cholesterol (2 months) plus 0.25% cholesterol and vitamin E (2 months)

Figure 4).

Extent of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortas of the four experimental groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Note that the control group has a value for atherosclerotic lesions to demonstrate the location of this group only; there were no atherosclerotic lesions in this group. *P<0.05, group I versus other groups; †P<0.05, group II versus other groups

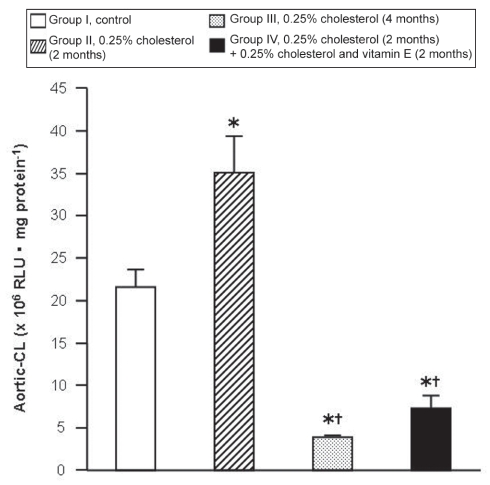

Aortic-CL

The aortic-CL of the four groups is summarized in Figure 5. The aortic-CL in group I was 21.56±2.09×106 RLU/mg protein. The values of aortic-CL were 62% higher in group II, 82% lower in group III and 66% lower in group IV compared with group I. The values in groups III and IV were 89% and 79% lower, respectively, than those in group II. The values in groups III and IV were similar. The data suggest that the antioxidant reserve decreased in group II compared with group I, but increased in groups III and IV compared with groups I and II. Vitamin E tended to normalize the antioxidant reserve, but not significantly.

Figure 5).

Chemiluminescent activity of aortic tissue (aortic-CL) of the four experimental groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. *P<0.05, group I versus other groups; †P<0.05, group II versus other groups. RLU Relative light unit

DISCUSSION

There were increases in the levels of serum TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C and TC/HDL-C in rabbits on a high-cholesterol diet similar to previous reports (1,2,4,19). The initial values of TC in groups II and III were higher compared with group I. The level of LDL-C in group IV was lower than in group I, and HDL-C levels in groups III and IV were lower than those in group I. These differences cannot be explained on the basis of weight, duration of acclimatization, living conditions, food intake or blood sampling procedures, because these conditions were similar in all groups. Vitamin E did not lower serum lipids in the present study. Similar findings have been reported previously (1,17–19,24,25).

The initial values of nonactivated WBCs in groups III and IV were different than in the other groups. There is no particular explanation for these differences because all the conditions were similar in all the groups. The high-cholesterol diet tended to increase the nonactivated WBC-CL. However, the high-cholesterol diet tended to decrease the zymosan-activated WBC-CL. Similar findings have been reported previously (19,26). Increases in the chemiluminescent activity of activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes in hypercholesterolemia have been reported (1). These differences could be due to the measurement of chemiluminescent activity in WBCs in the present study and measurements of chemiluminescent activity in polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the Prasad and Kalra study (1). Vitamin E had no effect on nonactivated WBC-CL or zymosan-activated WBC activity in the present study.

Aortic-CL is a measure of antioxidant reserve in the aortic tissue; an increase in aortic-CL reflects a decrease in this reserve and vice versa (27). Aortic-CL increased in group II, while it decreased in group III compared with group I. The data suggest that the antioxidant reserve decreased with 0.25% cholesterol intake for two months, while it increased with the same amount of cholesterol intake for a longer duration (four months). These findings are similar to those of Prasad (19). However, 0.25% cholesterol in other studies reduced the aortic-CL (26,28). These differences could be due to the 1% cholesterol diet in the fourth week of the 0.25% cholesterol regimen in the present study. A decrease in anti-oxidant reserve in group II on the high-cholesterol diet could be due to a decrease in the activity of antioxidants (superoxide dismutase [SOD], catalase and glutathione peroxidase [GSH-Px]) A decrease in these enzymes during ischemia has been reported (27,29). An increase in ROS during hyper-cholesterolemia (1,2,4) would exert oxidative stress leading to exhaustion of antioxidant enzymes. A decrease in the aortic-CL (an increase in antioxidant reserve) in groups III and IV may be due to increased activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase and GSH-Px). Increases in these antioxidant enzymes in the aortas of rabbits on a high-cholesterol diet have been reported (30). Vitamin E tended to increase the antioxidant reserve, but the increase was not significant. The slight increase with vitamin E may be due to reduction in oxidative stress because of the antioxidant activity of vitamin E.

The development of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortas was associated with hypercholesterolemia, duration of hypercholesterolemia, increase in the nonactivated WBC-CL and alteration of the aortic-CL. These observations are consistent with previous reports (1,2,4,19,26,28). The increases in non-activated WBC-CL suggest an increase in the levels of ROS that may induce endothelial injury (31), modulation of cell adhesion molecules (32,33), expression of chemotactic protein 1 (34) and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (35) that are involved in the genesis of atherosclerosis. Hypercholesterolemia increases the serum levels of asymmetrical dimethyl arginine (36), an inhibitor of nitric oxide (NO) synthesis (37), resulting in decreased production of NO. ROS produced by hypercholesterolemia (2,4) would also destroy NO. Thus, the reduction in NO could induce atherogenesis. NO reduces the development of atherosclerosis (38,39). The extent of atherosclerosis not only depends on the level of serum cholesterol, but also on the duration of hypercholesterolemia. The greater extent of atherosclerosis with longer duration compared to shorter duration of hypercholesterolemia could be due to increased exposure to ROS, which are involved in hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis (1,2,4). The duration of hypercholesterolemia-dependent extent of atherosclerosis has been reported previously (28).

Vitamin E did not reduce the progression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis in the present study. Similar observations were made by other investigators (11,16,18). Vitamin E supplementation in humans did not reduce the progression of common carotid artery intima-media thickness (16). Salonen et al (11) showed that vitamin E alone did not – but in combination with vitamin C did – reduce the progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in men. Vitamin E did not inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (18). In a study performed by Lonn et al (25), vitamin E was found to have a neutral effect on atherosclerotic progression in the carotid artery. Cyrus et al (17) reported a reduction in the progression of atherosclerosis in the aortas of LDL receptor-deficient mice with established vascular lesions. The controversial effects of vitamin E on progression of atherosclerosis may be due to the various reasons stated in the introduction.

The ineffectiveness of vitamin E in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis may be due to the conversion of alpha (α)-tocopherol to the α-tocopheroxyl radical, which is pro-oxidant (40,41). The tocopheroxyl radical is rapidly reduced by vitamin C to regenerate α-tocopherol (42). The possibility exists that vitamin C levels in the tissue are low; hence, pro-oxidant vitamin E radicals are elevated. Adverse effects of vitamin E on the antioxidant enzymes may also play a role in the ineffectiveness of vitamin E in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis. It decreases GSH-Px, increases catalase and has no effect on the SOD content of the aorta (30). Vitamin E did not slow the progression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis.

CONCLUSION

Atherosclerosis is associated with hyperlipidemia and increased oxidative stress. The ineffectiveness of vitamin E in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis was associated with the ineffectiveness of vitamin E in reducing serum lipids and oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Saskatchewan. The technical assistance of Ms Barbara Raney and Mr PK Chattopadhyay in the present study is highly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prasad K, Kalra J. Oxygen free radicals and hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis: Effect of vitamin E. Am Heart J. 1993;125:958–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90102-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad K, Kalra J, Lee P. Oxygen free radicals as a mechanism of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis: Effects of probucol. Int J Angiol. 1994;3:100–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg D. Antioxidants in the prevention of human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1992;85:2337–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.6.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad K. Reduction of serum cholesterol and hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis in rabbits by secoisolariciresinol diglucoside isolated from flaxseed. Circulation. 1999;99:1355–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad K, Lee P. Suppression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis by pentoxifylline and its mechanism. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Giovannucci E, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease in men. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1450–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1444–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushi LH, Folsom AR, Prineas RJ, Mink PJ, Wu Y, Bostick RM. Dietary antioxidant vitamins and death from coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1156–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephens NG, Parsons A, Schofield PM, Kelly F, Cheeseman K, Mitchinson MJ. Randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in patients with coronary disease: Cambridge Heart Antioxidant Study (CHAOS) Lancet. 1996;347:781–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Losonczy KG, Harris TB, Havlik RJ. Vitamin E and vitamin C supplement use and risk of all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality in older persons: The Established Population for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:190–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salonen JT, Nyyssönen K, Salonen R, et al. Antioxidant Supplementation in Atherosclerosis Prevention (ASAP) study: A randomized trial of the effect of vitamins E and C on 3-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2000;248:377–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: Results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Lancet. 1999;354:447–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20,536 high-risk individuals: A randomised placebo-controlled trial Lancet 200236023–33.12114037 [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Gaetano G, Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: A randomised trial in general practice. Lancet. 2001;357:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03539-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, Bosch J, Sleight P. Vitamin E supplementation and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:154–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, et al. VEAPS Research Group Alpha-tocopherol supplementation in healthy individuals reduces low-density lipoprotein oxidation but not atherosclerosis: The Vitamin E Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (VEAPS) Circulation. 2002;106:1453–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029092.99946.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cyrus T, Yao Y, Rokach J, Tang LX, Praticò D. Vitamin E reduces progression of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice with established vascular lesions. Circulation. 2003;107:521–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055186.40785.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Averill MM, Bennett BJ, Rattazzi M, et al. Neither antioxidants nor genistein inhibit the progression of established atherosclerotic lesions in older apoE deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad K.Vitamin E does not regress hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2009(In press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kapoor R, Prasad K. Role of oxyradicals in cardiovascular depression and cellular injury in hemorrhagic shock and reinfusion: Effect of SOD and catalase. Circ Shock. 1994;43:79–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee P, Prasad K. Suppression of oxidative stress as a mechanism of reduction of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis by cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Int J Angiol. 2003;12:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holman RL, McGill HC, Jr, Strong JP, Geer JC. Techniques for studying atherosclerotic lesions. Lab Invest. 1958;7:42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gornall AG, Bardawill CJ, David MM. Determination of serum proteins by means of the biuret reaction. J Biol Chem. 1949;177:751–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesaniemi YA, Grundy SM. Lack of effect of tocopherol on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:224–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lonn EM, Yusuf S, Dzavik V, et al. Effects of ramipril and vitamin E on atherosclerosis: The study to evaluate carotid ultrasound changes in patients treated with ramipril and vitamin E (SECURE) Circulation. 2001;103:919–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad K. A study on regression of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis in rabbits by flax lignan complex. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2007;12:304–13. doi: 10.1177/1074248407307853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad K, Lee P, Mantha SV, Kalra J, Prasad M, Gupta JB. Detection of ischemia-reperfusion cardiac injury by cardiac muscle chemiluminescence. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;115:49–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00229095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad K. Flax lignan complex slows down the progression of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic rabbits. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2009;14:38–48. doi: 10.1177/1074248408330541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao PS, Cohen MV, Mueller HS. Production of free radicals and lipid peroxides in early experimental myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1983;15:713–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(83)90260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantha SV, Prasad M, Kalra J, Prasad K. Antioxidant enzymes in hypercholesterolemia and effects of vitamin E in rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 1993;101:135–44. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90110-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren JS, Ward PA. Oxidative injury to the vascular endothelium. Am J Med Sci. 1986;292:97–103. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin A, Foxall T, Blumberg JB, Meydani M. Vitamin E inhibits low density lipoprotein-induced adhesion of monocytes to human aortic endothelial cells in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:429–36. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiu JJ, Wumg BS, Shyy JY, Hsieh HJ, Wang DL. Reactive oxygen species are involved in shear stress-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3570–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.12.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cushing SD, Berliner JA, Valente AJ, et al. Minimally modified low density lipoprotein induces monocyte chemotactic protein 1 in human endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5134–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajagopalan S, Meng XP, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG, Galis ZS. Reactive oxygen species produced by macrophage-derived foam cells regulate the activity of vascular matrix metalloproteinases in vitro. Implications for atherosclerotic plaque stability. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2572–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI119076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Böger RH, Bode-Böger SM, Brandes RP, et al. Dietary L-arginine reduces the progression of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits: Comparison with lovastatin. Circulation. 1997;96:1282–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallance P, Leone A, Calver A, Collier J, Moncada S. Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet. 1992;339:572–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Böger RH, Bode-Böger SM, Mügge A, et al. Supplementation of hypercholesterolaemic rabbits with L-arginine reduces the vascular release of superoxide anions and restores NO production. Atherosclerosis. 1995;117:273–84. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05582-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooke JP, Singer AH, Tsao P, Zera P, Rowan RA, Billingham ME. Antiatherogenic effects of L-arginine in the hypercholesterolemic rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1168–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI115937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burton GW, Ingold KU. Vitamin E: Applications of the principles of physical organic chemistry to the explanation of its structure and function. Acc Chem Res. 1986;19:194–210. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowry VW, Ingold KU, Stocker R. Vitamin E in human low-density lipoprotein. When and how this antioxidant becomes a pro-oxidant. Biochem J. 1992;288:341–4. doi: 10.1042/bj2880341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doba T, Burton GW, Ingold KU. Antioxidant and co-antioxidant activity of vitamin C. The effect of vitamin C, either alone or in the presence of vitamin E or a water-soluble vitamin E analogue, upon the peroxidation of aqueous multilamellar phospholipid liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;835:298–303. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]