Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of self-collected and health care worker (HCW)–collected nasal swabs for detection of influenza viruses and determine the patients' preference for type of collection.

Patients and Methods

We enrolled adult patients presenting with influenzalike illness to the Emergency Department at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, from January 28, 2011, through April 30, 2011. Patients self-collected a midturbinate nasal flocked swab from their right nostril following written instructions. A second swab was then collected by an HCW from the left nostril. Swabs were tested for influenza A and B viruses by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, and percent concordance between collection methods was determined.

Results

Of the 72 paired specimens analyzed, 25 were positive for influenza A or B RNA by at least one of the collection methods (34.7% positivity rate). When the 14 patients who had prior health care training were excluded, the qualitative agreement between collection methods was 94.8% (55 of 58). Two of the 58 specimens (3.4%) from patients without health care training were positive only by HCW collection, and 1 of 58 (1.7%) was positive only by patient self-collection. A total of 53.4% of patients (31 of 58) preferred the self-collection method over the HCW collection, and 25.9% (15 of 58) had no preference.

Conclusion

Self-collected midturbinate nasal swabs provide a reliable alternative to HCW collection for influenza A and B virus real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: Cp, crossing point; ED, emergency department; HCW, health care worker; ILI, influenzalike-illness; rRT-PCR, real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Influenza A and B are highly contagious respiratory viruses transmitted directly between infected and healthy individuals by large, virus-containing respiratory droplets generated by coughing or sneezing. Infection can also be transmitted indirectly by contact with contaminated surfaces followed by self-inoculation of ocular, nasal, or oral mucosa. Adults are typically infectious to others from 1 day before developing symptoms to approximately 5 days after symptom onset. Young children and immunocompromised persons may shed virus for even longer, with shedding reported for 10 or more days after symptom onset.1-4

Surveillance studies have identified health care setting–acquired influenza outbreaks.5 Influenza A and B viruses can spread rapidly between patients and health care workers (HCWs) in health care settings and may have serious and devastating consequences to high-risk populations. In particular, the elderly, critically ill, young children, and immunosuppressed patients including those receiving antineoplastic chemotherapy and/or solid organ or bone marrow transplant are at highest risk of developing serious influenza complications. The risks of infection-driven complications coupled with the clustering of these susceptible patients in the health care setting emphasize the need to minimize both patient and provider influenza virus exposures.1,6-8 The overall burden of health care facility–acquired influenza is unknown, but the potential economic and clinical impact is significant.3,5,7

A simple approach to prevent close contact in the health care setting and decrease unnecessary utilization of health care services during influenza season is to have select patient groups (eg, previously healthy adults with no underlying medical conditions) collect their own nasal swab and deliver it to a convenient drop-off location for testing. This could be facilitated by a well-designed telephone or online triage system that would obviate the need for a health care visit in selected patients. Use of this strategy would require that patient-collected samples have similar sample quality and test efficacy for detection of influenza A and B virus RNA compared with those collected by a trained HCW.

Few published studies examine the utility of self- or parent-collected swabs for bacteria and respiratory viral detection.9-14 These studies suggest that the self- or parent-performed swab collection method is an efficient, well-tolerated, and sensitive method for laboratory testing. However, there are no studies directly comparing the sensitivity of patient- and HCW-collected nasal or nasopharyngeal swabs for influenza A and B molecular testing. Therefore, our aim was to determine the degree of concordance between paired midturbinate nasal flocked swabs collected by the patient and an HCW using a real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assay for influenza A and B viruses. Furthermore, we conducted a survey to determine the patients' preference for self- vs HCW-collected specimens and their perceived degree of difficulty in collecting their specimen with a nasal flocked swab.

Patients and Methods

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Patients comprised adults aged 18 years and older presenting to the Saint Marys Emergency Department (ED), an academic ED that is part of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, with influenzalike illness (ILI) from January 28, 2011, to April 30, 2011. Influenzalike illness was defined by the presence of fever (measured at ≥37.7°C or reported by the patient) and either cough or sore throat per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (http://www.acha.org/ILI_Project/ILI_case_definition_CDC.pdf). Additional symptoms such as runny nose, nasal congestion, irritability, chills, body or muscle ache, lethargy, weakness, and vomiting were also recorded.

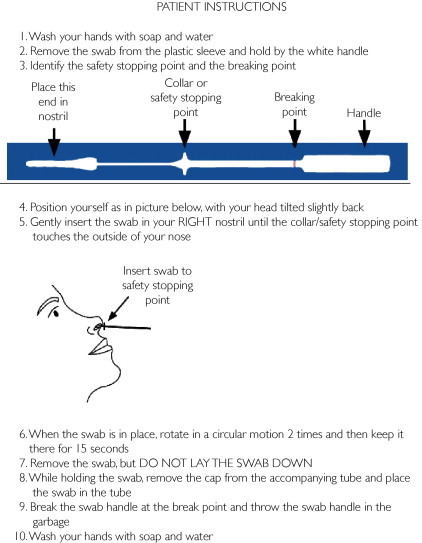

Participants first collected a midturbinate specimen with a nasal flocked swab (Diagnostic Hybrids, Athens, OH) from the right nostril following written instructions in English (Figure 1). All patients were observed during self-collection by the HCW for adherence to instructions. Language interpreters were used when necessary to read the instructions to the participant; however, no collection guidance was provided by the HCW or interpreter. A second midturbinate nasal flocked swab was collected immediately after the patient collection by a trained HCW from the left nostril. Each swab was placed in an individually labeled container with universal transport media (Diagnostic Hybrids, Athens, OH) and sent to the clinical microbiology laboratory for rRT-PCR testing. All specimens were transported within 2 hours of collection using the hospital pneumatic tube system and stored in the laboratory at 4οC until processed. After swab collection, the participants were asked to complete a questionnaire that subjectively rated the degree of difficulty in obtaining the self-collected swab (very difficult, difficult, easy, or very easy) and their preference for collection technique (self-collected, HCW-collected, or no preference). Demographic information including age, sex, race, occupation, and influenza vaccination status was also obtained. Patients who were dependent on oxygen via nasal cannula or were unable to provide verbal consent were excluded from the study. All positive results (regardless of collection method) were reported to the health care provider (primary care physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant) to ensure appropriate patient management.

FIGURE 1.

Patient instructions for midturbinate nasal swab collection.

Influenza rRT-PCR Testing

Paired specimens were processed in parallel in the clinical laboratory as part of routine patient specimen testing by technologists who were blinded to the type of collection technique. RNA was extracted by the MagNA Pure 2.0 instrument (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and then influenza A and B RNA was detected using the multiplex rRT-PCR Prodesse ProFlu+ assay (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA). The assay was modified for use on the LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science). A positive result is produced by this assay when amplification of viral RNA generates a fluorescent signal above the instrument detection threshold. The number of rRT-PCR cycles at which the signal crosses the threshold is known as the crossing point (Cp), which is inversely correlated to the logarithm of the initial copy number; higher Cps correlate with lower levels of viral RNA. Discordant results were resolved using previously described laboratory-developed influenza A and B rRT-PCR assays.15

Statistical Analyses

Percentage agreement between the patient- and HCW-collected nasal swabs was estimated with 95% score confidence intervals, and degree of agreement was summarized with the κ statistic. Viral detection level between patient- and HCW-collected samples was compared using the Cp values with a 2-sided paired t test, and the average difference between the methods was summarized with a 95% confidence interval. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9 or JMP version 8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Population Characteristics

Eighty-seven patients with a clinical diagnosis of ILI were considered for participation in this study. Of these, 10 (11.5%) were determined to be ineligible or declined to participate because of the presence of a nasal oxygen cannula, altered mental status, or lack of interest in the study. An additional 5 participants (5.7%) declined to participate because they were not comfortable obtaining their own nasal sample. Ultimately, paired midturbinate nasal flocked swabs were obtained from 72 patients. Median age was 39.5 years (range, 18-92 years), and 45.8% (33/72) were males (Table 1). Seventy-five percent of the study participants (54/72) were white. The summary of presenting symptoms is provided in Table 1. In addition to fever (required for inclusion), cough and body or muscle aches were the predominant symptoms. Only 50.0% of the study participants (36 of 72) had received the annual influenza vaccine.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Variables of Study Participants (n=72)

| Characteristic | Median (range) or No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic variable | |

| Age (y) | 39.5 (18-92) |

| Sex (male) | 33 (45.8) |

| Ethnicity (white) | 54 (75.0) |

| Occupation (health care worker) | 14 (19.4) |

| Clinical variable | |

| Primary (category A) symptomsa | |

| Fever | 72 (100) |

| Cough | 62 (86.1) |

| Sore throat | 48 (66.7) |

| Secondary (category B) symptoms | |

| Runny nose | 38 (52.8) |

| Nasal congestion | 44 (61.1) |

| Irritability | 19 (26.4) |

| Chills | 47 (65.3) |

| Body/muscle ache | 61 (84.7) |

| Lethargy | 33 (45.8) |

| Weakness | 39 (54.2) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 11 (15.3) |

| Received 2010-2011 influenza vaccine | 36 (50.0) |

Symptom category is based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition for influenzalike illness.

Adherence to Written Instructions

Four of the 72 patients (5.5%) showed gross nonadherence to the written instructions by inserting the swab only into the superficial nares and leaving it in place for 1 to 2 seconds. All 4 of these patient-collected specimens were negative for influenza A and B RNA by rRT-PCR. The HCW-collected swabs from 2 of these patients were positive for influenza RNA.

Concordance Between Patient and HCW Collection Methods

Twenty-five of the 72 total paired specimens (34.7%) were positive for influenza A or B RNA by at least one of the collection methods. Overall, 14 patients (19.4%) had prior health care training. To remove the potential bias of this training, these participants were excluded from the subsequent comparison analyses. In the subset without prior health care training, 20 of the 58 paired specimens collected (34.5%) were positive for influenza A or B RNA by at least one of the collection methods (Table 2). Seventeen of the 20 positive specimens (85.0%) were positive for influenza A virus and 3 (15.0%) were positive for influenza B virus by at least one of the collection methods. The overall qualitative agreement between collection methods was 94.8% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-98.2%), with a similar rate of influenza detection by both methods (κ=0.88).

TABLE 2.

Comparative Results of Influenza Viruses Detected in Patient- and HCW-Collected Midturbinate Nasal Flocked Swabs (n=58)a,b

| rRT-PCR result | Virus |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | Influenza B | ||

| Positive by HCW and patient collection | 15 | 2 | 17 (29.3%) |

| Positive by HCW collection alone | 1 | 1 | 2 (3.4%) |

| Positive by patient collection alone | 1 | 0 | 1 (1.7%) |

| Negative by HCW and patient collection | 38 (65.5%) | ||

HCW = health care worker; rRT-PCR = real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Data presented here exclude the 14 patients with prior health care training.

In the entire data set of 72 paired specimens, there were a total of 4 discordant results. Two paired specimens (1 obtained by a patient with prior health care training) were positive by the patient collection method but negative by the HCW collection method. Confirmatory testing on these discrepant specimens was performed in triplicate using an influenza A and B rRT-PCR laboratory-developed test, which showed that both collections were positive in at least 1 of the 3 replicates (data not shown), indicating that the discordance was due to low viral RNA levels in the specimen. There were also 2 paired specimens that were positive by the HCW collection and negative by the patient collection. The results did not change on repeat testing. As described earlier in this article, these 2 specimens were collected by patients who were nonadherent to the written instructions. When patients with prior health care training were removed from the analysis, there were 3 discordant results.

Comparison Between PCR Cp for Patient and HCW Collection Methods

The Cp data were compared between collection methods for the subset of patients without prior health care training. Among the 20 positive results for influenza A and B by at least one of the collection methods, 17 were positive by both methods and thus had Cp data that could be compared. Of concordant positive results, the HCW-collected specimens tended to have lower Cp ± SD as compared with patient-collected specimens (Cp, 24.8±4.2 vs 26.6±4.5, respectively; P=.02), indicating slightly higher RNA yield from the HCW-collected specimens (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Crossing Point Values for Paired Samples Positive for Both HCW and Patient Collection for Influenza A and B (n=17)a,b

| Collection method | Mean Cp±SD |

|---|---|

| HCW collection | 24.8±4.2 |

| Patient self-collection | 26.6±4.5 |

| Mean difference (95% CI) | 1.8 (0.36-3.15)c |

CI = confidence interval; Cp = crossing point; HCW = health care worker.

Data presented here exclude the 4 patients with prior health care training who had a positive influenza test result.

P=.02.

Patient Satisfaction Survey

The results of the patient satisfaction survey to assess perceived level of comfort of self-collection and preference for collection method are shown in Table 4. To avoid bias, the patients with prior health care training have been excluded. Only 6 (10.3%) of the patients graded the self-collection method as difficult, whereas the remaining 52 patients (89.7%) found it either easy or very easy. Most participants (53.4%) preferred the self-collection technique, a smaller fraction (20.7%) preferred the HCW collection, and 25.9% had no preference.

TABLE 4.

Patient-Perceived Level of Comfort for Self-Collection and Preference for Collection Method (n=58)a,b

| Variable | Survey selection | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ease of self-collection | Very easy | 13 (22.4) |

| Easy | 39 (67.2) | |

| Difficult | 6 (10.3) | |

| Very difficult | 0 (0) | |

| Collection method preference | Patient self-collect | 31 (53.4) |

| HCW collect | 12 (20.7) | |

| No preference | 15 (25.9) |

HCW = health care worker.

Data presented here exclude the 14 patients with prior health care training.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that HCW- and patient-collection techniques using midturbinate nasal flocked swabs were comparable for influenza A and B RNA detection by rRT-PCR. There was no significant difference in the overall positivity rate by either collection method. Although there were slight differences in the observed rRT-PCR Cps between patient- and HCW-collected specimens, this did not change the qualitative result. Further, most participants stated that the self-collection technique was easy or very easy to perform and preferred this method over the HCW collection method.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to directly compare the patient self-swabbing technique with HCW swabbing for respiratory virus molecular testing. However, several studies have shown in pediatric patients that parental collection of midturbinate, nasal, and/or throat specimens for testing viruses such as human metapneumovirus, influenza A virus, influenza B virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, and adenoviruses is an efficient and acceptable method of conducting vaccine efficacy studies and other community-based respiratory virus research.10,11,14 Esposito et al14 directly compared parent-collected midturbinate nasal swabs with pediatrician-collected swabs for influenza detection by rRT-PCR and demonstrated moderately high sensitivity (89.3%) and high specificity (97.7%) for the parental collection technique. Further, they demonstrated that direct involvement of parents in the collection process increased the child's acceptance of the midturbinate nasal flocked swab. Our study results are consistent with those in the Esposito study in that we found similar concordance between patient- and HCW-collected specimens with a patient preference for the self-collection method.

Like Esposito et al, we used the recently introduced midturbinate nasal flocked swabs for sample collection. Unlike traditional swabs that are constructed by wrapping absorbent rayon fibers around a sturdy applicator, flocked swabs have no internal mattress core to entrap the sample. As a result, the entire sample stays close to the surface and elutes quickly and completely into testing media. Both swabs have a similar diameter. Recent studies have indicated that midturbinate nasal flocked swabs have high sensitivity and specificity for detection of common respiratory viruses by direct immunofluorescent antibody and molecular assays compared with nasopharyngeal swabs, while only being inserted to half the depth.14,16-18 Thus, the midturbinate nasal flocked swabs provide a less invasive yet sensitive alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs and are more amenable to patient self-collection. The swabs used in this study have a safety collar to indicate the depth of insertion and are also available in a pediatric version for children aged 2 years or younger.

In our patient subset without prior health care training, we observed 3 discordant results. The 2 paired specimens that were positive by HCW collection and negative by patient collection were anticipated at the time of collection because both patients showed gross nonadherence to the written instructions. This indicates that quality of collection is important for influenza virus molecular testing. An additional paired specimen was positive by the patient collection but negative by the HCW collection. Confirmatory testing on this third specimen indicated that the discrepancy was due to the low level of virus present, as evidenced by a high Cp.

A potential bias in this study is that we did not randomize the participants for collection by nostril side. However, there is no evidence in the literature that virus shedding is affected by the side of sample collection. Our study also had a few limitations. First, the study had a relatively small number of patients with influenza B infection compared with those with influenza A, although it is unlikely that the method of collection would have any influence on detection of influenza by type. Second, most study participants were white, and hence, the results may not be generalizable to broader populations with disparate socioeconomic, educational, and racial backgrounds. Third, since midturbinate nasal flocked swabs were employed in this study, extrapolation of results to commercially available molecular systems that require use of nasopharyngeal swabs may require further validation studies. Finally, low level of virus in specimens can result in discrepant results between HCW and self-collection methods, as observed in this study.

Our study results have a number of practical implications. First, the patient-collection strategy may reduce time spent in the outpatient clinic or emergency department (ED) and thus reduce influenza exposure risks to other vulnerable patients and HCWs. We view this as a considerable advantage because outpatient clinic and ED waiting rooms often collectively group immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients together, and waiting times are commonly prolonged. Patient protection is a priority, and minimizing unintentional exposures to influenza virus is a primary objective of this testing approach. Second, self-collection may provide a more time-efficient testing approach, which could lead to an earlier diagnosis of influenza infection and initiation of time-sensitive antiviral treatment. Third, this strategy could decrease the burden on busy outpatient clinics and EDs during peak influenza season if combined with a triage method to determine which patients should be tested and if self-collection is an appropriate strategy. Finally, patient collection may be useful for large epidemiological or vaccine efficacy studies in which patient or parent collection may ensure better compliance. Of note, this method potentially could be used for detection of other respiratory viruses in addition to influenza A and B, such as respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, and coronavirus. This should be examined further using laboratory-developed or commercially available individual and multiplex molecular respiratory platforms.

Despite the advantages of self-collection, we encountered potential barriers for successful implementation of this technique. Five potential participants were not comfortable obtaining a midturbinate nasal flocked swab themselves and opted not to participate in the study for this reason. Therefore, self-collection programs may wish to provide an alternative mechanism for HCW collection when necessary. It is also important to note that some patients may encounter difficulties in reading or interpreting written instructions or opening the swab packaging. Consideration should be given to providing instructions in multiple languages and providing easy-to-open packaging. Picture-based instructions may be created for a wider variety of patients, including illiterate patients, patients with limited reading skills, children, and those for whom English is not the first language. Further, pictures may improve adherence to instructions by avoiding misinterpretations of written instructions even among literate patients.

Self-collection in lieu of an office or ED visit is not appropriate for all patients, such as those with complicated illness or risk factors for severe disease. It may also not be useful to test all patients who present with an ILI if treatment is going to be prescribed regardless of the laboratory result. Diagnosing influenza, however, can avoid unnecessary antibacterial therapy in the appropriate early settings. Practice-specific algorithms can be used to direct patients to appropriate testing (or nontesting) options.

On the basis of our experience, we propose a model for “personalized patient care” by providing a structured system for patient-collected nasal swabs (Figure 2). Patients could first be screened over the phone by a trained HCW using a standardized triage questionnaire to determine whether self-collection is appropriate for that particular patient according to an assessment of risk factors and disease severity. If treatment decisions will not be influenced by the test result, then testing may not be indicated. If the patient is eligible for self-collection, then the patient or a caregiver would be offered the option of obtaining a swab kit with instructions from an easy access point such as a community-based clinic, pharmacy, drive-through facility, or even a specialized vending machine. If patients are not comfortable obtaining their own specimen, then they may be offered an office visit. After self-collection, the patient or caregiver would drop the swab off at a convenient location designed to maximize testing turnaround time. After testing is performed, the laboratory result could be communicated to the patient or a health care provider (primary care physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant) who could offer further instruction and decide whether treatment is appropriate. At our institution, a prescription for oseltamivir may be generated by a health care provider and sent to the laboratory along with the patient's swab specimen.15 If the test result is positive for influenza, then the laboratory will fax the prescription to the patient's pharmacy. If the test result is negative, then the prescription is not faxed. This serves to link the prescription to the positive test result and avoid unnecessary drug use. The patients obtain their test results by calling a registered phone number and providing their unique patient identification number. The automated phone service informs the patient when a prescription has been sent to the pharmacy on the basis of a positive laboratory result. It is easy to envision how this system could be further modified to suit the needs of the clinical practice and the patients it serves. This same approach has been used for many years at our institution for detection of group A streptococci in patients suspected to have streptococcal pharyngitis.19

FIGURE 2.

Proposed model for patient-collected midturbinate nasal swabs for influenza polymerase chain reaction assay. An influenzalike illness (A) prompts the patient to call the Nurse Triage Center (B), where a nurse assesses the patient's condition via a standardized phone questionnaire. If eligible, the patient is offered the opportunity to self-collect a nasal swab in lieu of an office visit. A prescription for oseltamivir is generated and placed with a swab kit. The patient or caregiver obtains the swab kit from an easy-access point (C) and uses the midturbinate nasal flocked swab to obtain a sample following written instructions (D). The swab is then delivered to the clinical microbiology laboratory for polymerase chain reaction assay (E), along with a precompleted prescription. If the swab is positive for influenza, the prescription is sent to the patient's pharmacy. The patient receives the test result by an automated phone system (F), along with information to pick up the prescription if the test is positive (G).

In addition to clinical benefits, patient self-collection may alleviate cost burdens to the health care system and patient. At our institution, a visit to the ED for an uncomplicated ILI costs the health care system approximately 1.8 times more than an outpatient office visit, which in turn costs 4 times more than a visit to an express care clinic. In comparison, the salary and indirect costs incurred during a 10-minute telephone call with a registered nurse cost the health care system 5 times less than a visit to an express care clinic. Therefore, the cost incurred to the health care system is significantly reduced when the nurse-triage model is used. One would expect that the charge to the patient would be similarly decreased.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that patient-collected midturbinate nasal swabs show similar efficacy for detection of influenza A and B virus RNA by rRT-PCR as HCW-collected midturbinate nasal swabs and that this collection method is well accepted by patients. Offering selected patients the opportunity to collect their own specimen for influenza testing in place of an office or ED visit may reduce viral exposure to other patients and HCWs, reduce or eliminate unnecessary wait times for patients, decrease the financial burden and workload on EDs and outpatient clinics, and decrease the cost to the patient.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory technologists and assistants at the Virology and Initial Processing Laboratory at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, for the technical support during this study.

Footnotes

Dr Dhiman is now with Summa Health System, Akron, OH.

Grant Support: This study was supported by the Ann and Leo Markin Named Professorship fund (F.R.C.).

Supplemental Online Material

Author Interview Video

References

- 1.Harper S.A., Fukuda K., Uyeki T.M., Cox N.J., Bridges C.B. Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-8):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki F.Y., Boivin G. Influenza virus shedding: excretion patterns and effects of antiviral treatment. J Clin Virol. 2009;44(4):255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poland G.A., Tosh P., Jacobson R.M. Requiring influenza vaccination for health care workers: seven truths we must accept. Vaccine. 2005;23(17-18):2251–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weingarten S., Riedinger M., Bolton L.B., Miles P., Ault M. Barriers to influenza vaccine acceptance: a survey of physicians and nurses. Am J Infect Control. 1989;17(4):202–207. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(89)90129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridges C.B., Kuehnert M.J., Hall C.B. Transmission of influenza: implications for control in health care settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(8):1094–1101. doi: 10.1086/378292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson W.W., Shay D.K., Weintraub E. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stott D.J., Kerr G., Carman W.F. Nosocomial transmission of influenza. Occup Med (Lond) 2002;52(5):249–253. doi: 10.1093/occmed/52.5.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salgado C.D., Farr B.M., Hall K.K., Hayden F.G. Influenza in the acute hospital setting. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(3):145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faden H. Comparison of midturbinate flocked-swab specimens with nasopharyngeal aspirates for detection of respiratory viruses in children by the direct fluorescent antibody technique. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(10):3742–3743. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01520-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert S.B., Allen K.M., Druce J.D. Community epidemiology of human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus NL63, and other respiratory viruses in healthy preschool-aged children using parent-collected specimens. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e929–e937. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert S.B., Allen K.M., Nolan T.M. Parent-collected respiratory specimens—a novel method for respiratory virus and vaccine efficacy research. Vaccine. 2008;26(15):1826–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchta R.M. Use of a rapid strep test (First Response) by parents for detection of streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(11):829–833. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198911000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz H.P., Clancy R.R. Accuracy of a home throat culture program: a study of parent participation in health care. Pediatrics. 1974;53(5):687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esposito S., Molteni C.G., Daleno C. Collection by trained pediatricians or parents of mid-turbinate nasal flocked swabs for the detection of influenza viruses in childhood. Virol J. 2010;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zitterkopf N.L., Leekha S., Espy M.J., Wood C.M., Sampathkumar P., Smith T.F. Relevance of influenza A virus detection by PCR, shell vial assay, and tube cell culture to rapid reporting procedures. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(9):3366–3367. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00314-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu-Diab A., Azzeh M., Ghneim R. Comparison between pernasal flocked swabs and nasopharyngeal aspirates for detection of common respiratory viruses in samples from children. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2414–2417. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00369-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heikkinen T., Marttila J., Salmi A.A., Ruuskanen O. Nasal swab versus nasopharyngeal aspirate for isolation of respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(11):4337–4339. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4337-4339.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waris M.E., Heikkinen T., Osterback R., Jartti T., Ruuskanen O. Nasal swabs for detection of respiratory syncytial virus RNA. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(11):1046–1047. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.113514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhl J.R., Adamson S.C., Vetter E.A. Comparison of LightCycler PCR, rapid antigen immunoassay, and culture for detection of group A streptococci from throat swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(1):242–249. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.242-249.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Author Interview Video