Aortic aneurysms (AAs) are life-threatening permanent dilations of the aorta, frequently defined by a diameter of 1.5 times normal 1. They are subdivided anatomically into thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). The underlying pathogenesis differs between the two anatomical sites; for TAAs, the histological abnormality is medial degeneration, characterized by loss of smooth muscle cells, fragmented and diminished elastic fibers, and accumulation of proteoglycans 2, 3. Genetic mutations are the underlying cause of TAAs in many young or middle-aged patients 4. In contrast, the histopathology of AAAs is dominated by severe intimal atherosclerosis, chronic transmural inflammation, and remodeling of the elastic media 2, 3. Analysis of gene expression demonstrated that AAAs and TAAs exhibit distinct patterns, with most changes relative to normal aortas unique to each disease 3. However, several risk factors are shared between TAAs and AAAs, including smoking, hypertension, male sex and aging. 2. The age and gender dependence is illustrated by the prevalence of AAAs 2.9 to 4.9 cm in diameter, ranging from 1.3% in men age 45 to 54 to 12.5% at ages 75 to 84. For women the prevalence for the same age groups is 0% and 5.2% respectively 5. The prevalence of TAAs also increases with age, and is higher in men 6.

If untreated, AAs can expand and eventually rupture, resulting in death rates as high as 90%; in 2009, mortality in the US from aortic aneurysms and dissections was more than 10,500 7. Both expansion rates and rupture rates of AAs increase with aneurysm size. Diagnosis of AAs generally involves anatomical imaging, typically ultrasound or computed tomography angiography (CTA), and once diagnosed risk stratification involves measurement of diameter by CTA 8. There has been controversy concerning the value of population screening for AAAs, but the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) 9 and several other trials 10 have provided evidence in support of screening programs. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for men aged 65-75 years who have ever smoked 11. Currently, the threshold for surgical treatment of AAs is predicated on the aneurysm diameter; for TAAs, thresholds of 5.5 to 6 cm for the ascending aorta and 6.0 to 6.5 for the descending aorta are commonly used 6, while for AAAs the threshold is 5.0 to 5.5 cm. However, some AAs smaller than these thresholds rupture, while others larger than the thresholds are stable; better tools other than anatomical size to predict rupture of an individual AA are thus needed 8, 12. The increasing use of endovascular repair of AAs may also impact clinical decision making with respect to timing of repair 13.

The application of molecular imaging to the cardiovascular system has grown rapidly since the mid 1990s 14. While the major focus has been detection of vulnerable plaque, a number of publications have used molecular probes to image AAs, both in animal models and in humans. A variety of animal models for AA provide a substrate for the development of new diagnostics and therapeutics 15. Ranging from mice to pigs, they include a spectrum of surgically and biologically-induced models 15. The power of molecular imaging to perform longitudinal studies has facilitated studies on the rate of AA development, and offers the potential for new methods to assess AA status based on function rather than simply anatomical size. Functional imaging could help to predict which patients are unstable and will need surgery sooner, or can be treated medically rather than surgically. In addition, the capacity for longitudinal imaging of functional biology in animal models of AA can be expected to facilitate the screening of novel treatments, while monitoring biological activity in patients may provide information on whether a specific therapy are working much more rapidly than simply measuring the change in AA size as a function of time, facilitating personalized treatment tailored to the individual patient. This review will summarize recent progress in the application of molecular imaging to AA in animal models and patients.

Animal studies

A number of different targeting strategies have been employed for molecular imaging of AAs. This section will address the use of tracers focused on the various biological targets offered by AAs in animal models.

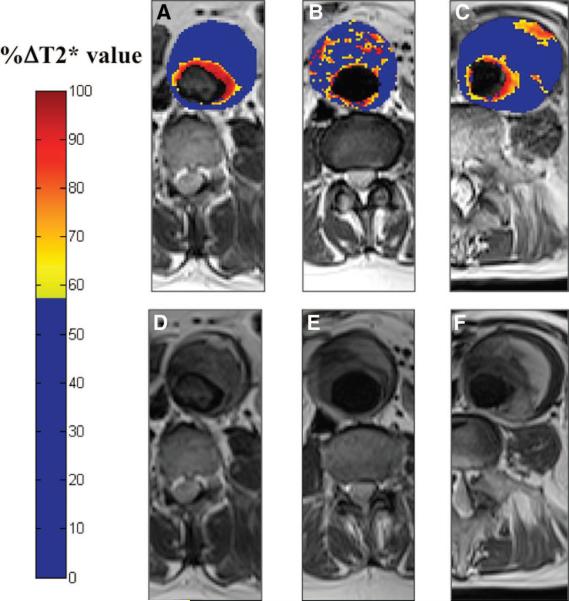

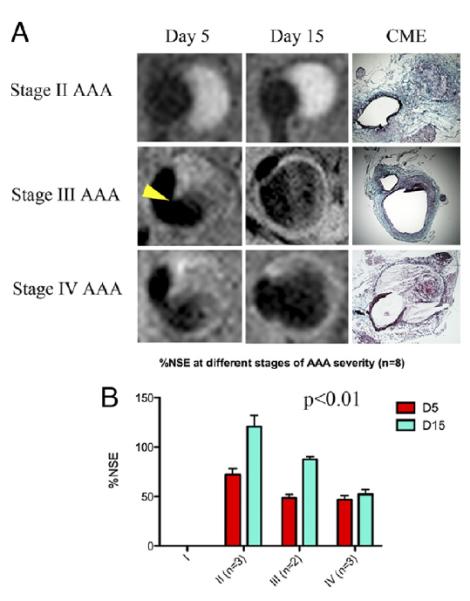

Extracellular matrix

Turnover of the extracellular matrix (ECM) plays a major role in AA development 16, making ECM components an attractive target for molecular imaging. Klink et al took advantage of a recently-described mouse model of AAA employing a combination of angiotensin II (Ang II) infusion and transforming growth factor β neutralization to assess the utility of nanoparticles (NP) functionalized with a collagen-specific protein, CNA-35 17. The targeting ligand is derived from 2 domains of a collagen adhesion protein derived from Staphylococcus aureus. Intravenous injection of gadolinium-containing NP targeted with CAN-35 resulted in significantly greater T1-weighted signal enhancement in the aneurysmal wall compared to non-specific NP, and the CNA-35 NP were shown histologically to co-localize with type 1 collagen. In a proof of concept experiment, animals were imaged at days 5 and 15 after induction of AAA, and images correlated with pathology (Figure 1). Higher uptake of CNA-35 NP correlated with stable Stage II aneurysms with high collagen uptake, while ruptured Stage IV aneurysms showed little uptake and low collagen content 17.

Figure 1.

A: Typical images of stage II, III, and IV abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) obtained after CNA-35 injection at day 5 and day 15 of AAA development. Corresponding histological sections stained with combined Masson elastin are shown in the third column. B: Quantification of aneurysm severity (increasing from stage I to IV) and normalized signal enhancement percentage (%NSE) relative to CNA-35 injection. From Klink et al17 with permission from Elsevier.

Matrix metalloproteases

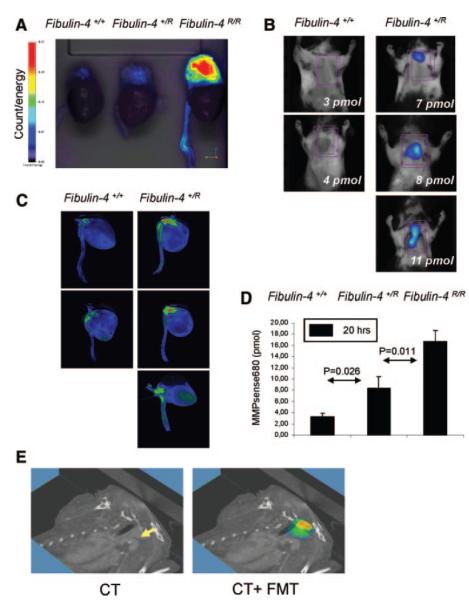

Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) are overexpressed in both TAAs and AAAs, and contribute to ECM degradation and aneurysm progression. Bazeli et al used P947, a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor labeled with gadolinium through a chelator, to target MMPs in expanding AAAs in rat aortas perfused with elastase 18. Uptake of the targeted chelate into the aortic wall was shown by MR imaging to be significantly greater than for a scrambled targeting peptide or non-targeted Gd-DOTA. The area of contrast enhancement co-localized with MMP activity shown by in situ zymography 18. Sheth et al used an enzyme-activated optical imaging probe and intravital surface reflectance imaging to study the relationship between MMP activity and AAA growth 19. They found a linear relationship between MMP activity and optical signal. They also demonstrated suppression of MMP activity by daily oral administration of the MMP inhibitor doxycycline using endovascular imaging with the optical probe 19. Protease-activated near infra-red fluorescence probes have also been used to image TAAs, in conjunction with multimodal employing fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) and computed tomography co-registration 20. In a mouse model of reduced expression of the ECM protein fibulin 4, Kaijzel et al found graded increases in FMT signal within aneurysmal lesions from control mice to heterozygous fibulin-4 R/+ and homozygous fibulin-4 R/R mice (Figure 2). Increased MMP activity was detectable prior to increase in vessel size. Ex vivo zymography confirmed a similar graded increase in MMP activity 20.

Figure 2.

Graded increase in MMPs within the aneurysmal lesions in fibulin-4+/R and fibulin-4R/R mice ex vivo. B, Quantification of FMT-derived fluorescence of excited fluorochrome in the aorta. C, Ex vivo analysis of the MMP increase within the aortic arch area in fibulin-4+/+ and fibulin-4+/R mice. D, Isosurface concentration mapping from reconstructed tomographic images showing a graded increase in activation of signal within the aortic arch area of fibulin-4+/R and fibulin-4R/R mice compared to wild-type fibulin-4+/+ animals E, Three-dimensional FMT-CT co-registration of the heart and aorta of a heterozygous fibulin-4+/R mouse. From Kaijzel et al 20 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health

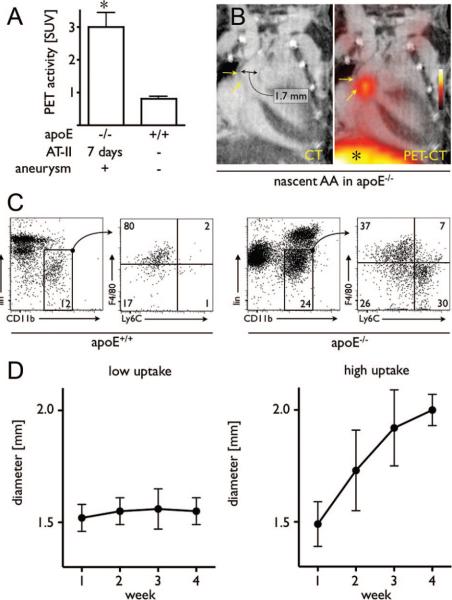

Inflammatory cells

The infiltration of macrophages and monocytes into the vessel wall plays an important role in the progression of both TAAs and AAAs 21, 22. Positron emission tomography in conjunction with macrophage-targeted iron oxide NP labeled with 18F-fluorine permits detection of macrophages and monocytes with very high sensitivity. Nahrendorf et al studied an experimental model of aortic aneurysms consisting of apoE−/− mice infused with Ang II, which resulted in both TAAs and AAAs, to address the relationship between inflammation and aneurysm growth 23. They found that uptake of NP was significantly greater in aneurysms compared to wild-type aorta (Figure 3A, B). The number of macrophages and monocytes was increased >20 fold in the aneurysmal aortas of apoE−/− mice relative to wild-type, and the profile was dominated by pro-inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes rather than the resident macrophages predominantly seen in wild-type aortas (Figure 3C, D).They also found that the PET signal of aneurysms imaged at 7 days predicted the rate of expansion; aneurysms with low uptake showed little expansion over the subsequent 3 weeks, while high nanoparticle uptake was associated with significant expansion 23.

Figure 3.

Imaging in mice with early-stage aneurysms undergoing 7 days of Ang-II administration. A, PET signals from aneurysms and from wild-type mice. B, Representative PET-CT images of a nascent AA. * indicates liver signal. C, Flow cytometric analysis of leukocytes in the aorta of wild-type mice (left 2 plots) and apoE−/− mice (right 2 plots) after 7 days of Ang-II administration. The gated regions in the left plots for each mouse type depict the monocyte/macrophage population, which were further analyzed for expression of the monocyte surface marker Ly6-C and the macrophage marker F4/80 (plots on the right). Lin indicates lineage antigens (CD90/B220/CD49b/NK1.1/Ly-6G). Numbers contained within the gated regions of the plots (left plots) indicate the percentage of living cells (macrophages/monocytes). Numbers in the quadrants (right plots) indicate the percentage of monocytes/macrophages in each gate. D, Serial CT angiography after PET-CT on day 7 in Ang-II treated apoE−/− mice. Left panel shows the diameter of aneurysms with low PET signal; right panel shows diameter of aneurysms with high signal. From Nahrendorf et al 23 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health

Integrins and receptors

Both αvβ3 integrin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor are up-regulated on neoangiogenic vascular endothelial cells and on inflammatory macrophages. Kitigawa et al used nanoparticles made from human ferritin nanocages and conjugated with Arg-Gly-Asp peptide (RGD) to target the αvβ3 integrin and image experimental AAAs in Apo E−/− mice treated with Ang II 24. Using in situ and ex vivo fluorescence imaging following i.v. administration of NP labeled with the fluorescent dye Cy5.5, they demonstrated increased uptake of RGD-targeted relative to non-targeted NP; by histology, they showed that the targeted NP were co-localized both with macrophages and with neoangiogenesis 24.

Tedesco et al used an engineered single-chain VEGF homo-dimer labeled with Cy5.5 to target the VEGF receptor in the mouse Ang II infusion model 25. Using near infra-red fluorescent imaging, they showed that signal intensity was increased in aneurismal aorta relative to remote uninvolved segments or vessels in control mice. Furthermore, signal intensity increased as a function of vessel diameter in aneurysmal segments 25.

Thrombus

The presence of intraluminal thrombus (ILT) is a very common feature in AAAs, with reported frequencies ranging from 75-98% 26, 27. ILTs are associated with weakening of the arterial wall and rupture of AAAs, possible through increased proteolysis and infiltration of inflammatory cells 28. ILT thickness in patients undergoing elective repair for AAAs was correlated with activity of MMP 9 and the concentration of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloprotease I (TIMP I) in the adjacent aneurysm wall 29. The thrombus is biologically active, undergoing constant renewal at the luminal interface 30. Distal embolization can also occur, although the frequency is unclear, with reported incidence varying from 3% to 29% 31. One of the earliest uses of molecular imaging to image AAAs employed 99mTc-Annexin-V to target platelet activation and consequent exposure of phosphatidylserine at the interface with circulating blood. Using the elastase-perfused rat model and single photon emission computed tomography, Sarda-Mantel et al showed a five-fold increase in target to background ratio for aneurysms relative to normal vessels in control rats 32. Ex vivo studies on human thrombi excised during surgery for AAA repair showed a similar pattern of annexin labeling at areas where activated platelets and leukocytes accumulate 32. The P-selectin-specific targeting agent fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide derived from brown seaweed, has also been used to image thrombus in AAA. Rouzet et al showed that 99mTc-fucoidan detected thrombi in elastase-treated rats with a median target to background ratio of 3.6 33.

Human studies

Studies performed in patients so far have been restricted to AAAs, and can be broken down into two groups; first, the use of small and ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles targeted to inflammatory macrophages and monocytes infiltrating the AAA in conjunction with MR imaging; and second, the use of FDG as a marker of inflammation in conjunction with positron emission tomography.

Iron oxide nanoparticles

Richards et al 34 employed uptake of ultrasmall paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) nanoparticles to assess whether inflammation correlated with AAA growth in stable patients with asymptomatic AAAs from 4-6.6 cm. Using T2*-weighted MR imaging, they found three patterns of USPIO uptake; periluminal uptake only, diffuse patchy uptake within the intraluminal thrombus, and discrete focal uptake distinct from the periluminal region (Figure 4). While the initial diameter of the aneurysms was similar for all three groups, the annual growth rate for patients with distinct mural uptake was 3-fold greater than for the other two groups of patients 34. Uptake of USPIO into AAAs, resulting in decreases in T2 and T2* times, was also demonstrated by Sadat et al in a small feasibility study 35.

Figure 4.

Top: Color maps (A through C) showing representative abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) slices from patients in each of the 3 groups alongside the corresponding T2W anatomic images (D through F). The color scale represents the magnitude of the change in T2* value, with blue indicating minimal change and red indicating a large change in T2* value. A distinctive pattern is seen for each patient group: A, Group 1 shows a large change in T2* value only in the periluminal area; B, Group 2, diffuse patchy changes in T2* throughout the intraluminal thrombus but no distinct focal area of USPIO uptake affecting the aortic wall; and C, Group 3, discrete focal area of USPIO uptake involving the wall of the AAA that is distinct from the periluminal region. This patient subsequently died suddenly from presumed ruptured AAA. Bottom: Relationship of diameter and growth rate with patient group. Initial aneurysm diameters (open bars) are similar for the 3 groups, but the aneurysm growth rates (solid bars) are higher for patients in group 3 (0.66 cm/y) compared with those in groups 1 (0.22cm/y) and 2 (0.24 cm/y). From Richards et al 34 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

Nchimi et al used SPIO nanoparticles to assess leukocyte phagocytic activity in patients undergoing surgery for AAA 36. Injection of SPIO resulted in decreased T2*-weighted signal intensity in the luminal sublayer and thrombus. In some cases the thrombus had a multilayered appearance, and this was correlated with higher matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 activity in the thrombus. Semiquantitative analysis of the decrease in thrombus T2*-weighted signal showed a correlation with levels of cells positive for CD68 and for CD66b, and also with tissue levels of MMP-2 and -9 36.

FDG

FDG is taken up by inflammatory cells such as monocytes and leukocytes in an insulin-insensitive manner. Consequently, FDG uptake in the fasted state has been proposed as a marker of risk for AAA progression and rupture, with higher FDG uptake associated with inflammation, aortic wall instability and clinical symptoms 37, 38. Elevated levels of FDG uptake have also been associated with regions of wall stress in both TAAs and AAAs 39. However, others have shown that FDG uptake is low in asymptomatic AAAs with a diameter close to surgical indications (mean diameter 4.9cm), perhaps reflecting decreased cell density in large AAAs 40. Similarly, Kotze et al found an inverse relationship between FDG uptake and future growth rate of AAAs 41. The potential role for FDG and PET in monitoring AAAs is thus unclear at present.

Summary

Animal studies have demonstrated that a wide range of tracers aimed at different pathophysiological elements can be used to detect AAs. These molecular imaging probes have the potential to provide complementary functional information that goes beyond the anatomical information obtained through diagnostic echocardiography or CT studies. While anatomical imaging cannot predict future expansion of aneurysms, the functional information provided by molecular imaging agents may be able to predict future events. For some agents, for example CNA-35 targeting of collagen and 18F-labeled NP targeted to macrophages 23, proof-of-principle studies have confirmed that molecular imaging can provide information on AA functional status. For the collagen-targeted tracer, stable Stage II AAAs have a higher signal than ruptured Stage IV AAAs, reflecting the less-compromised status of the ECM 17. For 18F -NP, low uptake was associated with low growth, while AAs that took up high levels of tracer expanded rapidly 23. More extensive studies, including experiments in additional models of AA, will be needed to confirm the potential prognostic value of these and other molecular imaging strategies.

Translation to human studies

Each imaging technology used for molecular imaging has strengths and weaknesses related to factors such as spatial resolution, sensitivity, and depth of penetration, and these factors have been the subject of a recent comprehensive review 42. In some cases the imaging modalities used to study AAs in animal models, for example MR, PET and SPECT, could be readily translated towards clinical application. For PET and SPECT tracers, the lower spatial resolution can make image interpretation problematic, and so they are likely to be used in hybrid imaging with either CT or MRI to provide anatomical information. This allows accurate localization of the molecular probe, and quantification of tracer in the target. The rapid expansion in availability of PET/CT and SPECT/CT hybrid systems makes this increasingly feasible, while hybrid PET/MRI systems are just starting to become available commercially. Quantification of tracer uptake will be important for longitudinal studies and for comparisons between patients, and it also been proposed that quantification of tracer uptake, for example by standardized uptake value (SUV) could potentially be used to set thresholds for when a patient should undergo repair 23.

For tracers detected using optical methods, the limited depth penetration through tissue would preclude external detection in humans, and require a catheter-based approach. While catheters have been developed for intravascular imaging of vulnerable plaque 43, the invasiveness of the approach may not lend itself readily to screening and assessment of AAs. However, the use of optical methods in animal models can provide a relatively high throughput and inexpensive modality for use in longitudinal studies for drug development and testing. Hybrid imaging with an anatomical imaging method such as CT can also help to overcome the limited spatial resolution of optical imaging. Enzyme-activatable probes can also provide high signal to noise ratios since the non-activated probe gives no signal.

Some probes currently being used for optical imaging could be readily adapted to other imaging modalities, allowing transfer of the probe to imaging large animals and humans; for example, the human ferritin nanocages employed by Kitigawa et al to target αvβ3 integrin can readily incorporate iron oxide for MR imaging 44, and single-chain VEGF homo-dimer for VEGF receptor imaging should be amenable to radiolabeling for PET imaging. Pros and cons for different molecular imaging agents, and their potential for clinical translation, are summarized in the Table.

Table

| Probe | Probe Target | Imaging Modality |

Pros | Cons | Clinical potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAN-35 NP | Collagen | MRI | High spatial resolution | Lower sensitivity | Yes? Bacterial origin of peptide may be problematic |

| P947-gadolinium | Broad spectrum MMP |

MRI | High spatial resolution | Lower sensitivity | Yes |

| SPIO, USPIO | Macrophage | MRI | High spatial resolution | Lower sensitivity | Yes, SPIO/USPIO have been used in patients |

| Enzyme activated | MMP | Optical | No background signal until activated. High throughput possible |

Limited depth of imaging, low spatial resolution |

Would require catheter-based imaging |

| RGD-nanocage | αvβ3 integrin | Optical | High throughput possible | Limited depth of imaging, low spatial resolution |

Could be adapted to MR or PET imaging |

| Single- chain VEGF | VEGF receptor | Optical | High throughput possible | Limited depth of imaging, low spatial resolution |

Could be adapted to MR or PET imaging |

| 99mTc-Annexin-V | Thrombus | SPECT | High detection sensitivity | Low spatial resolution, quantification requires hybrid imaging |

Yes, 99mTc-Annexin-V has been used in patients |

| 99mTc-Fucoidan | Thrombus | SPECT | High detection sensitivity | Low spatial resolution, quantification requires hybrid imaging |

Yes |

| 18F-nanoparticle | Macrophage., monocyte |

PET | High detection sensitivity, simple quantification |

Low spatial resolution | Yes, iron oxide NP have been used in patients |

| 18FDG | Inflammatory cells | PET | High detection sensitivity, simple quantification |

Low spatial resolution, low specificity |

Already used in patients |

Initial studies in humans show promise for the potential of molecular imaging in patient stratification, particularly the pilot study from Richards et al demonstrating that discrete focal USPIO uptake in areas distinct from the periluminal region was associated with high rates of aneurysm expansion 34. Patients with this pattern of USPIO uptake might thus be candidates for earlier surgical or endovascular intervention, while patients with only periluminal uptake, or diffuse patchy uptake within the intraluminal thrombus, might be candidates for continued monitoring and medical treatment. Larger prospective studies will be needed to determine whether this promising finding holds true. Molecular imaging agents could also potentially help in assessing efficacy of drugs, using molecular imaging signals such as decreased MMP activity or altered USPIO uptake as a surrogate endpoint to predict whether a patient is responding to treatment. The demonstration of the efficacy of doxycycline in reducing MMP activity in mice AAAs illustrates this potential role 19. Other questions include whether there is potentially a role for molecular imaging in understanding the increased risk for AAAs in smokers 45.

The etiology of TAAs and AAAs differs; AAAs are generally the result of chronic inflammatory atherosclerosis, and are associated with diffuse diathesis 46, while TAAs reflect . This raises the question of whether different molecular imaging agents will be needed for the two disease entities. However, increased uptake of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and monocytes has been demonstrated in TAA as well as AAA 22, and elevated MMP activity has also been demonstrated. This is supported by the studies in Ang II-treated Apo E−/− mice, where 18F -NP uptake was observed in both TAAs and AAAs 20, and in mice with decreased fibulin 4 expression where graded increases in MMP activity were found as fibulin 4 decreased 20. Thus while human molecular imaging studies have so far been largely restricted to patients with AAAs, many of the imaging agents under development might be expected to be applicable to TAAs as well as AAAs. However, since animal models do not necessarily recapitulate human disease fully, this will need to be confirmed in clinical studies.

In summary, initial studies in animals and humans have shown promise for the molecular imaging of AAs, and potentially for discriminating those at high risk for rupture from stable aneurysms.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Sources of Funding The author is employed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, Shah DM, Hollier L, Stanley JC. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on reporting standards for arterial aneurysms, ad hoc committee on reporting standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13:452–458. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.26737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo DC, Papke CL, He R, Milewicz DM. Pathogenesis of thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1085:339–352. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Absi TS, Sundt TM, 3rd, Tung WS, Moon M, Lee JK, Damiano RR, Jr., Thompson RW. Altered patterns of gene expression distinguishing ascending aortic aneurysms from abdominal aortic aneurysms: Complementary DNA expression profiling in the molecular characterization of aortic disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:344–357. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagle KA. Rationale and design of the national registry of genetically triggered thoracic aortic aneurysms and cardiovascular conditions (GENTAC) Am Heart J. 2009;157:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor LM, Jr., White CJ, White J, White RA, Antman EM, Smith SC, Jr., Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic) Circulation. 2006;113:e463–654. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanath VS, Oh JK, Sundt TM, Iii, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:465–481. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60566-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochanek HC, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung HC. Deaths: Preliminary data for 2009. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2011;59:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moxon JV, Parr A, Emeto TI, Walker P, Norman PE, Golledge J. Diagnosis and monitoring of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Current status and future prospects. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:512–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton HA, Buxton MJ, Day NE, Kim LG, Marteau TM, Scott RAP, Thompson SG, Walker NM. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11522-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dabare D, Lo TTH, McCormack DJ, Kung VWS. What is the role of screening in the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms? Interacti Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:399–405. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lederle FA. Screening for AAA in the USA. Scand J Surg. 2008;97:139–141. doi: 10.1177/145749690809700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klink A, Hyafil F, Rudd J, Faries P, Fuster V, Mallat Z, Meilhac O, Mulder WJ, Michel JB, Ramirez F, Storm G, Thompson R, Turnbull IC, Egido J, Martin-Ventura JL, Zaragoza C, Letourneur D, Fayad ZA. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:338–347. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouriel K. Randomized clinical trials of endovascular repair versus surveillance for treatment of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. J EndovascTher. 2009;16:I-94–I-105. doi: 10.1583/08-2600.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buxton DB, Antman M, Danthi N, Dilsizian V, Fayad ZA, Garcia MJ, Jaff MR, Klimas M, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Sinusas AJ, Wickline SA, Wu JC, Bonow RO, Weissleder R. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on the translation of cardiovascular molecular imaging. Circulation. 2011;123:2157–2163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.000943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trollope A, Moxon JV, Moran CS, Golledge J. Animal models of abdominal aortic aneurysm and their role in furthering management of human disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011;20:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellenthal FA, Buurman WA, Wodzig WK, Schurink GW. Biomarkers of AAA progression. Part 1: Extracellular matrix degeneration. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:464–474. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klink A, Heynens J, Herranz B, Lobatto ME, Arias T, Sanders HM, Strijkers GJ, Merkx M, Nicolay K, Fuster V, Tedgui A, Mallat Z, Mulder WJ, Fayad ZA. In vivo characterization of a new abdominal aortic aneurysm mouse model with conventional and molecular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2522–2530. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazeli R, Coutard M, Duport BD, Lancelot E, Corot C, Laissy JP, Letourneur D, Michel JB, Serfaty JM. In vivo evaluation of a new magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent (p947) to target matrix metalloproteinases in expanding experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:662–668. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ee5bbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheth RA, Maricevich M, Mahmood U. In vivo optical molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activity in abdominal aortic aneurysms correlates with treatment effects on growth rate. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaijzel EL, van Heijningen PM, Wielopolski PA, Vermeij M, Koning GA, van Cappellen WA, Que I, Chan A, Dijkstra J, Ramnath NW, Hawinkels LJ, Bernsen MR, Lowik CW, Essers J. Multimodality imaging reveals a gradual increase in matrix metalloproteinase activity at aneurysmal lesions in live fibulin-4 mice. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:567–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.933093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu K, Mitchell RN, Libby P. Inflammation and cellular immune responses in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:987–994. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000214999.12921.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He R, Guo D-C, Sun W, Papke CL, Duraisamy S, Estrera AL, Safi HJ, Ahn C, Maximilian Buja L, Arnett FC, Zhang J, Geng Y-J, Milewicz DM. Characterization of the inflammatory cells in ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms in patients with Marfan syndrome, familial thoracic aortic aneurysms, and sporadic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:922–929. e921. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Marinelli B, Leuschner F, Robbins CS, Gerszten RE, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK, Weissleder R. Detection of macrophages in aortic aneurysms by nanoparticle positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:750–757. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitagawa T, Kosuge H, Uchida M, Dua MM, Iida Y, Dalman RL, Douglas T, McConnell MV. RGD-conjugated human ferritin nanoparticles for imaging vascular inflammation and angiogenesis in experimental carotid and aortic disease. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0495-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tedesco MM, Terashima M, Blankenberg FG, Levashova Z, Spin JM, Backer MV, Backer JM, Sho M, Sho E, McConnell MV, Dalman RL. Analysis of in situ and ex vivo vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression during experimental aortic aneurysm progression. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1452–1457. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.187757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hans SS, Jareunpoon O, Balasubramaniam M, Zelenock GB. Size and location of thrombus in intact and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:584–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harter LP, Gross BH, Callen PW, Barth RA. Ultrasonic evaluation of abdominal aortic thrombus. J Ultrasound Med. 1982;1:315–318. doi: 10.7863/jum.1982.1.8.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labruto F, Blomqvist L, Swedenborg J. Imaging the intraluminal thrombus of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Techniques, findings, and clinical implications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.01.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan JA, Abdul Rahman MNA, Mazari FAK, Shahin Y, Smith G, Madden L, Fagan MJ, Greenman J, McCollum PT, Chetter IC. Intraluminal thrombus has a selective influence on matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors (tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases) in the wall of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2012;26:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Touat Z, Ollivier V, Dai J, Huisse M-G, Bezeaud A, Sebbag U, Palombi T, Rossignol P, Meilhac O, Guillin M-C, Michel J-B. Renewal of mural thrombus releases plasma markers and is involved in aortic abdominal aneurysm evolution. The American Journal of Pathology. 2006;168:1022–1030. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baxter BT, McGee GS, Flinn WR, McCarthy WJ, Pearce WH, Yao JST. Distal embolization as a presenting symptom of aortic aneurysms. The American Journal of Surgery. 1990;160:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarda-Mantel L, Coutard M, Rouzet F, Raguin O, Vrigneaud JM, Hervatin F, Martet G, Touat Z, Merlet P, Le Guludec D, Michel JB. 99mTc-annexin-V functional imaging of luminal thrombus activity in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2153–2159. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237605.25666.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouzet F, Bachelet-Violette L, Alsac JM, Suzuki M, Meulemans A, Louedec L, Petiet A, Jandrot-Perrus M, Chaubet F, Michel JB, Le Guludec D, Letourneur D. Radiolabeled fucoidan as a p-selectin targeting agent for in vivo imaging of platelet-rich thrombus and endothelial activation. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1433–1440. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.085852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards JM, Semple SI, MacGillivray TJ, Gray C, Langrish JP, Williams M, Dweck M, Wallace W, McKillop G, Chalmers RT, Garden OJ, Newby DE. Abdominal aortic aneurysm growth predicted by uptake of ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide: A pilot study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:274–281. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.959866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadat U, Taviani V, Patterson AJ, Young VE, Graves MJ, Teng Z, Tang TY, Gillard JH. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of abdominal aortic aneurysms–a feasibility study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nchimi A, Defawe O, Brisbois D, Broussaud TK, Defraigne JO, Magotteaux P, Massart B, Serfaty JM, Houard X, Michel JB, Sakalihasan N. Mr imaging of iron phagocytosis in intraluminal thrombi of abdominal aortic aneurysms in humans. Radiology. 2010;254:973–981. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakalihasan N, Hustinx R, Limet R. Contribution of PET scanning to the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Semin Vasc Surg. 2004;17:144–153. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeps C, Essler M, Pelisek J, Seidl S, Eckstein H-H, Krause B-J. Increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in abdominal aortic aneurysms in positron emission/computed tomography is associated with inflammation, aortic wall instability, and acute symptoms. J Vascr Surg. 2008;48:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu XY, Borghi A, Nchimi A, Leung J, Gomez P, Cheng Z, Defraigne JO, Sakalihasan N. High levels of 18F-FDG uptake in aortic aneurysm wall are associated with high wall stress. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palombo D, Morbelli S, Spinella G, Pane B, Marini C, Rousas N, Massollo M, Cittadini G, Camellino D, Sambuceti G. A positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) evaluation of asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms: Another point of view. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.05.038. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotze C, Groves A, Menezes L, Harvey R, Endozo R, Kayani I, Ell P, Yusuf S. What is the relationship between 18F-FDG aortic aneurysm uptake on PET/CT and future growth rate? Eur J NuclMed Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1799-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinusas AJ, Bengel F, Nahrendorf M, Epstein FH, Wu JC, Villanueva FS, Fayad ZA, Gropler RJ. Multimodality cardiovascular molecular imaging, part I. Circ: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:244–256. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.824359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaffer FA, Calfon MA, Rosenthal A, Mallas G, Razansky RN, Mauskapf A, Weissleder R, Libby P, Ntziachristos V. Two-dimensional intravascular near-infrared fluorescence molecular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis and stent-induced vascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2516–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terashima M, Uchida M, Kosuge H, Tsao PS, Young MJ, Conolly SM, Douglas T, McConnell MV. Human ferritin cages for imaging vascular macrophages. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1430–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lederle FA, Nelson DB, Joseph AM. Smokers’ relative risk for aortic aneurysm compared with other smoking-related diseases: A systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nordon I, Brar R, Taylor J, Hinchliffe R, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Evidence from cross-sectional imaging indicates abdominal but not thoracic aortic aneurysms are local manifestations of a systemic dilating diathesis. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:171–176. e171. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]