Abstract

A 64-year-old man was admitted with fever, weight loss, fatigue and night sweats. He was known to have rheumatoid arthritis and had been taking methotrexate for 1 year. He had worked in Saudi Arabia until 1994 and had been living in Spain for 6 months every year. Clinical examination showed an enlarged spleen. Routine investigations showed pancytopaenia. Serial blood cultures were negative. CT scan confirmed splenomegaly and was otherwise unremarkable. Bone marrow biopsy revealed Leishmania amastigote consistent with a diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. After discussing with the hospital for tropical diseases (HTD), he was started on liposomal amphotericin B. Following two infusions of amphotericin B, he started improving as his fever, night sweats and weakness had settled. He was then discharged and followed up in HTD clinic 4 weeks later where he was found to be consistently improving.

Background

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is extremely rare in the UK with an annual incidence of two cases per year. There have been a few case reports of VL in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on biological therapy but only two cases have been reported in patients on methotrexate. It is important to realise that patients on immuno-suppressive medications are at increased risk of acquiring these infections and can have re activation of a latent infection, therefore obtaining a travel history is very important. Early recognition of this condition is also very important as untreated VL has a mortality of more than 80%.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old Caucasian gentleman was admitted in January 2009, with a 3-month history of shortness of breath, fatigue, gum bleeding, loss of appetite and weight loss. He also had intermittent night sweats and fever. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in 1991, which was treated with methotrexate for 2 years. His disease then went into remission until February 2008 when he had a flare up requiring re treatment with methotrexate. At the same time he developed a vasculitic rash on his chest, which was considered to be due to rheumatoid vasculitis. He had been given a course of steroids for exacerbation of arthritis, which he finished 6 weeks before presentation. He was a life-long non-smoker and took no alcohol. He was independently mobile and his day-to-day function was not limited despite a long history of rheumatoid arthritis. He was a retired construction manager and worked in Saudi Arabia for 10 years until 1994. Since then he had been living in Spain for 6 months every year and spent the remaining time in the UK.

Investigations

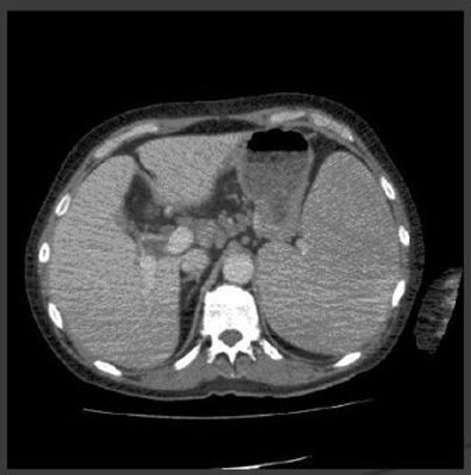

On examination he was pale, there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. There was no pigmentation. There was evidence of bilateral symmetrical arthropathy of metacarpo-phalangeal joints with no sublaxation at the wrist joints. Chest was clear. There were no murmurs or added sounds on cardiac auscultation. On abdominal examination, he had significantly enlarged spleen (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CT abdomen.

His initial blood investigations showed pancytopaenia with haemoglobin 6.9, white cell count 2.2, neutrophil 0.7 and platelet count of 90 000. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was raised at 134. Liver function tests showed a low albumin at 27 and renal function was normal. Chest x-ray was normal.

Serial blood cultures grew no organism. Urine examination was unremarkable. CT scan of the abdomen showed enlarged spleen, small volume mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which was thought to be radiologically in significant. Trans-thoracic echocardiogram was normal.

In view of pancytopaenia, haematology opinion was sought and a bone marrow biopsy was performed, which showed leishmania amastigote consistent with a diagnosis of VL (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Marrow biopsy.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis included lymphoma, felty’s syndrome with hypersplenism, infective endocarditis, drug induced myelosuppression or tropical diseases like malaria, brucellosis, tuberculosis, Q fever and enteric fever.

Treatment

The patient was initially treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and also had a blood transfusion. After discussion with hospital of tropical diseases (HTD), he was started on liposomal amphotericin B. It was also recommended that he have HIV test because of association of HIV with leishmaniasis, which was performed and was negative.

During his inpatient stay he was also seen by maxillofacial surgeon for gum bleed and no intervention was suggested apart from regular mouthwashes and the gum bleed was believed not to be relevant to the disease.

Outcome and follow-up

Following two courses of intravenous amphotericin B he had started to improve and consequently discharged to have further infusions in the day unit. He was followed up in HTD 4 weeks later when he was found to be improving as his weight had improved significantly, he did not have any further night sweats, his spleen had reduced in size and his Hb had improved.

Six months following his admission he was seen again in the HTD clinic and was consistently improving.

Discussion

VL is a parasitic disease of tropics and subtropics and is endemic in 88 countries worldwide.1 The natural transmission of the parasites is through phlebotomine sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus (old world) or Lutzomyia (New World). Infection may be also transmitted through the bloodborne route (sharing of syringes, blood transfusion), transplacentally, or through solid organ transplantation2 3

VL is caused by Leishmania donovani, L infantum or L chagasi, although up to 30 different species are recognised which can infect mammals. L infantum is the commonest species in the Mediterranean.

Depending on the organs involved, it has been classified as mucosal, muco-cutaneous and VL. The visceral form is the most serious form of the disease with a mortality of 80% if untreated.

Climate, geographic, socioeconomic and behavioural factors determine leishmania endemicity, Immunity plays an important role in expression of the disease as it is found in older and very young population in the endemic areas. HIV is now a recognised risk factor for development of VL, with 3–7% of patients with HIV at risk of developing VL.4

VL is well recognised but un-commonly imported disease in the UK. In HTD, London, there were 39 cases seen during 1985–2004. Of these cases, 30 were acquired in Mediterranean countries (13 in Spain). More than half of these patients had been tourist to these endemic regions. Therefore we believe, that our patient although lived in Saudi Arabia till 1994, acquired leishmaniasis during his stay in Spain. The Mediterranean VL endemic zone account for a small proportion of VL cases globally, but it is an important holiday destination for the British, driving the epidemiology of the imported infection.5

Other than HIV, impaired immunity due to other conditions for example, neoplastic diseases; organ transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy increase the risk of VL manifestation after Leishmania infection.6 7

VL is a rare diagnosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.8 However four cases of VL in patients with rheumatoid arthritis have been reported in association with antiTNF therapy9 and only two cases have been reported in association with methotrexate.10

The clinical manifestation of VL is mostly similar in both endemic areas and non-endemic areas, in host with low immunity due to any reason. Symptoms include intermittent fever; weight loss, diarrhoea and the clinical signs include generalised lymphadenopathy, hepato-splenomegaly. Symptoms can be non-specific for months before a diagnosis is made and the disease severity can vary from mild infection to a fulminant disease. It can be especially difficult to diagnose in non-endemic areas due to low index of suspicion and a wide differential list because of non-specificity of the symptoms as in our case.

The most commonly used method for diagnosing VL is demonstrating the parasite in the relevant tissues for example, bone marrow aspirate, splenic aspirate or lymph node by light microscopy using giemsa or leishman stains. Bone marrow aspirate is a safe method with sensitivity between 60 and 85%. Splenic aspirate has a sensitivity of 95% but carries a small risk of fatal haemorrhage in less experienced hands. These techniques related to the direct detection of the parasite can be used with similar sensitivity in the case of diagnosis HIV co-infection.

Other methods used include detection of parasite DNA using PCR that has a high sensitivity of 96%, which can be reach upto 100% on combining with ELISA. This technique was applied in diagnosis of VL with promising results using peripheral blood and can be used in HIV co infected patients with good result. Other uses of PCR based technique include quantitative assessment of parasite burden, which can be used in assessment of treatment response and can aid in the detection of relapse of the condition.11

Serology is a useful means of diagnosing VL and is used widely in endemic settings. It also has a role in diagnosing in non-endemic countries. Two serological tests used include direct agglutination test (DAT) and K39 dipstick test with sensitivities of 94 and 93%, respectively.12 DAT measures antileishmania antibody titres using a freeze-dried antigen and K39 dipstick test detects antibodies to a specific 39 amino acid sequence. These tests can be safely used to diagnose VL but there are regional variations, as these are more sensitive in Asia than Sudan, possibly because Sudanese patients produce low antibody titres. In addition, the tests remain positive after infection for years, so cannot be used to detect re-infection or relapse. Furthermore serology can be negative in up to half of HIV patients with VL.

Immunodiagnosis is another modality aimed at detecting parasite antigens using specific Leishmania antibodies or Leishmania-specific cell mediated immunity by skin tests.

Pentavalent antimonials, meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate, are the mainstay of treatment in VL-endemic areas outside India, with efficacy rate of 90–95%. The main advantage of these medications is low cost but the disadvantages include intramuscular routes of administration, prolonged hospitalisation and occasionally serious side effects including cardiac arrhythmias, elevated hepatic transaminases blood levels, pancreatitis and pneumonitis.13 14 Resistance has been an issue especially in India.

Conventional amphotericin B provides cure rates of 90–95% but prolonged duration of administration, prolonged hospitalisation and frequent adverse effects, including infusion-related fever and chills; nephrotoxicity and hypokalaemia 13 15 limit its use in all countries.

Liposomal amphotericin B, which is selectively taken up by the reticuloendothelial cells limits these systemic side effects and provides cure rates of up to 100%. Currently it is the treatment of choice in Europe and USA. In addition to less side effects, other advantages include shorter duration of course, improved convenience of the patient and reduction of healthcare associated costs. However in developing countries, cost remains a major factor and conventional amphotericin B is still used in preference to the liposomal formulation of amphotericin B.

Liposomal amphotericin B is also the first line treatment in immuno-compromised host with VL especially with HIV co-infection and solid organ transplant. Response to treatment is as good as 90% in both groups, however relapse is seen more commonly seen in HIV co infected patients, where secondary prophylaxis with the same is recommended.16–18

Finally, immuno suppressive treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis provides clinical benefit but puts them at risk of serious opportunistic infections; therefore early recognition of these conditions is very important as untreated VL has a mortality of more than 80%. Although VL is rare in Caucasian population, it should be one considered to be an important differential diagnosis in patients with suggestive symptoms returning from endemic areas.

Learning points.

-

▶

Leishmaniasis is rare in the UK but should be suspected in visitors from endemic areas.

-

▶

Immuno suppressive treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis provides clinical benefit but puts them at risk of leishmaniasis.

-

▶

Early recognition of these conditions is very important as untreated VL has a high mortality.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Desjeux P. The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2001;95:239–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos OD, Coutinho CER, Madeira MF, et al. Leishmaniasis treatment-a challenge that remains: a review. Parasitol Res 2008;103:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori S, Cascio A, Parravicini C, et al. Leishmaniasis among organ transplant recipients. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:191–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo R, Laguna F, López-Vélez R, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in those infected with HIV: clinical aspects and other opportunistic infections. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2003;97 (Suppl 1):99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik AN, John L, Bruceson AD, et al. Changing patterns of visceral leishmaniasis, United Kingdom, 1985–2004. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:1257–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harms G, Schönian G, Feldmeier H. Leishmaniasis in Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:872–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisser M, Khanlari B, Terracciano L, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: a threat to immunocompromised patients in non-endemic areas?. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:751–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baixauli Rubio A, Rodríguez Górriz E, Campos Fernández C, et al. [Rare opportunistic disease in a patient treated with immunosuppressive therapy for rheumatoid arthritis]. An Med Interna 2003;20:276–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagalas V, Kioumis I, Argyropoulou P, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis infection in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:1344–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venizelos I, Tatsiou Z, Papathomas TG, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with methotrexate. Int J Infect Dis 2009;27:e169–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santarém N, Cordeiro-da-Silva A. Departmento de Bioquimica, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade do Porto, Rua Anibla Cunha 164, 4099-030 Porto, Portugal. Instituto de Biologia Molecular e Celular, Universidade do Porto, Diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis Rua do Campo Alegre 823, 4150-180 Porto, Portugal.

- 12.Chappuis F, Rijal S, Soto A, et al. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of the direct agglutination test and rK39 dipstick for visceral leishmaniasis. BMJ 2006;333:723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kafetzis DA, Maltezou HC. Visceral leishmaniasis in paediatrics. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2002;15:289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chappuis F, Sundar S, Hailu A, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control? Nat Rev Microbiol 2007;5:873–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olliaro PL, Guerin PJ, Gerstl S, et al. Treatment options for visceral leishmaniasis: a systematic review of clinical studies done in India, 1980-2004. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:763–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laguna F. Treatment of leishmaniasis in HIV-positive patients. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2003;97(Suppl 1):S135–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Giorgio C, Faraut-Gambarelli F, Imbert A, et al. Flow cytometric assessment of amphotericin B susceptibility in Leishmania infantum isolates from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 1999;44:71–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourgeois N, Lachaud L, Reynes J, et al. Long-term monitoring of visceral leishmaniasis in patients with AIDS: relapse risk factors, value of polymerase chain reaction, and potential impact on secondary prophylaxis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:13–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]