Abstract

Objective

To determine if programmed cell death 4 (PDCD-4) is altered in autologous leiomyoma and myometrial tissues and microRNA-21's (miR-21) role in PDCD-4 expression, apoptosis and translation.

Design

Laboratory research.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Patient(s)

Myometrial and leiomyoma tissues from patients with symptomatic leiomyomata.

Interventions(s)

Tissue analysis and miR-21 knockdown in cultured immortalized myometrial (UtM) and leiomyoma (UtLM) cells.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

MiR-21 and PDCD-4 mRNA and protein expression.

Result(s)

Leiomyoma tissues robustly expressed the full-length 51kDA isoform of PDCD-4, while normal myometrial tissue had negligible expression Consistent with autologous tissues, UtLM cells expressed elevated miR-21 and a similar pattern of PDCD-4 compared to UtM cells. Knockdown of miR-21 increased PDCD-4 levels in UtM cells and UtLM cells, indicating that it can regulate PDCD-4 expression. Loss of miR-21 also increased cleavage of caspase-3 (apoptosis marker) and increased phosphorylation of elongation factor -2 (marker of reduced translation) in both cell lines.

Conclusions

Elevated leiomyoma miR-21 levels are predicted to decrease PDCD-4 levels, thus leiomyomas differ from other tumors where loss of PDCD-4 is associated with tumor progression. Our studies indicate regulation of PDCD-4 expression is not a primary miR-21 function in leiomyomas, but instead miR-21 is able to impact cellular apoptosis and translation, through unknown targets, in a manner consistent with its involvement in the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids.

Keywords: microRNA, uterine fibroids, leiomyoma, PDCD-4, miR-21

Introduction

Human uterine leiomyomas (ULMs) are benign tumors located in the smooth muscle of the myometrium. They are clinically apparent in ~25% of reproductive-aged women but the overall incidence is between 70 and 80% (1). ULMs can cause abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pressure, pain, and reproductive dysfunction and they are the most common risk factor for hysterectomy resulting in 200,000 annually in the U.S. (2). While the etiology that leads to the development of ULMs is unknown, the ovarian steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, as well as genetic abnormalities have both been implicated in the development of ULMs (3-6). Numerous studies have implicated microRNAs (miRNA) as critical regulators of many disease processes including cancer (7, 8). A consistent finding observed across ULM miRNA expression studies comparing leiomyoma tissue to autologous myometrial tissue is the induction of miR-21 in ULM tissue (9-11). Aberrant expression of miR-21 in a number of human cancers including breast, cervical, ovarian, hepatocellular, esophageal, prostate and lung B cell lymphoma has led to miR-21 being referred to as an oncomiR (7, 8). While miR-21 has received a great deal of attention due to its role in other cancers, little is known regarding the role that miR-21 plays in ULM etiology.

Many functionally important direct targets of miR-21 that regulate apoptosis and/or tumorigenesis have been identified. These include reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs, sprouty 2, phosphatase and tensin homologue, T lymphoma and metastasis gene 1 and tropomyosin 1 amongst others (8). Another well studied miR-21 target transcript is programmed cell death-4 (PDCD-4) (8, 12). PDCD-4 has many important functions including cell cycle regulation, neoplastic transformation and apoptotic regulation (13). In-vitro cell culture models have also implicated PDCD-4 in inhibition of tumorigenesis, through down regulation of carbonic anhydrase II and urokinase receptor (14). Confirmation of its tumor suppressive role has been demonstrated in mouse models in which overexpression of PDCD-4 in the epidermis led to significant reductions in skin carcinogenesis (15). Expression analysis of PDCD-4 has shown that it is down regulated in a variety of tumors providing additional confirmation of PDCD-4's function as a tumor suppressor (8, 12, 16). In the single study examining miR-21 target genes in ULM, Pan et. al. (17) observed a slight decline in PDCD-4 mRNA levels in cultured primary leiomyoma cells compared to cultured myometrial cells, while paradoxically, showing that PDCD-4 mRNA levels were increased in a transformed leiomyoma cell line and in a leiomyosarcoma cell line, inconsistent with its role in tumor suppression. This study, however, did not address whether PDCD-4 protein expression was regulated by miR-21 in these cell lines (17). Lastly, no study has examined PDCD-4 expression patterns in isolated leiomyoma or myometrial tissue.

This study investigated miR-21 and PDCD-4 expression patterns in hTert-immortalized leiomyoma (UtLM) and myometrial (UtM) cell lines as well as in leiomyoma and myometrial tissues. Additionally, we determined if miR-21 could post-transcriptionally regulate PDCD-4 and whether miR-21 could elicit effects on apoptosis or translation within the immortalized cell lines. Our results showed a distinct pattern of protein expression for PDCD-4 in leiomyoma tissues when compared to autologous myometrial tissues. Moreover, we observed that miR-21 affected global translation and regulation of apoptosis within myometrial and leiomyoma cells, and PDCD-4 did not reflect the anticipated inverse correlation with miR-21 levels.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Myometrial and leiomyoma tissue samples were obtained from healthy premenopausal women with symptomatic leiomyomas at the time of elective hysterectomy at Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, IL). All tissues were collected under consent for use of discarded human tissue that was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Carle Foundation Hospital. Each tissue sample was assigned an arbitrary identification number on the day it was received and patient information was known only to the physician or physician's nurse. However, physicians provided information about the age of the patient and any medications. All patients were premenopausal (21-50 years old) and had not been on any hormonal medications for six months prior to their hysterectomy. Tissues collected were from both proliferative (53%) and secretory (47%) stages of the menstrual cycle. Upon biopsy, leiomyoma (n=11) and myometrial (n=12) tissues were placed in TRIZOL and processed to RNA in the laboratory (18), most of these tissues were from paired tissues. An additional, 11 autologous pairs of leiomyoma and myometrium tissues were used for protein analysis, seven of the sets of samples for the RNA and proteins samples were derived from the same patients.

Cell Lines and Tissue Culture

The hTert-immortalized leiomyoma cells (hereafter referred to as UtLM) were generated as described previously (38) and were generously provided by Dr. Darlene Dixon (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle, NC). The hTert-immortalized myometrial cells (UtM), generously provided by Dr. Rainey (Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA), were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA.) supplemented with 7.5% NaHCO3, 1% antibiotic antimycotic (Gibco), and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (19). UtLM cells were cultured in MEM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 300ug/ml of G418 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), 1% essential amino acids (Gibco), 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 1% L-Glutamine, 15% FBS and 1% vitamins (Gibco). Medium was replaced every 2-3 days and cells were passaged using 1X Trypsin (Gibco) as needed.

Locked nucleic acid (LNA) inhibitors were purchased from Exiqon (http://www.exiqon.com/mirna-inhibitors). The inhibitor specific for miR-21 (LNA-miR-21), has a complementary sequence to miR-21, 5’-CAACATCAGTCTGATAAGCT-3’ (bolded bases indicate position of locked nucleic acids), which binds to and blocks miR-21 action. The non-specific inhibitor LNA-scramble, which does not recognize any known RNA transcripts, was used as a control. UtM and UtLM cells were transfected in serum free medium (DMEM/F12 or MEM) at 85% confluence with LNA oligonucleotides (40 nM) using lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) per the manufacturer's protocol. Eight hours after transfection, medium was replaced with appropriate culture media for each cell line. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were harvested and RNA was isolated using Trizol (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer's protocol and stored at -80° C until use. Cells were lysed in a hyptonic buffer containing 20mM NaCL, 25mM Tris-HCl and 0.1% Triton X-100. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 minutes to pellet cellular debris. The protein supernatant was stored at -80° until use.

Western Blotting

Protein concentration was determined for each sample using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules CA). Proteins (15 ug/sample) were denatured by diluting the appropriate volume in 4X Sample Buffer (4ml of glycerol, 0.8g of SDS, 2.5 ml of 1M Tris-HCl, 8ml of H20, .05% w/v bromophenol blue) and heating at 95° C for 5 minutes. Proteins were resolved in a 10% SDS PAGE gels in 1X running buffer (4.5g Tris-Base, 21.6 glycine, 2g SDS, 2L dH2O) and then transferred to PVDF membrane using transfer buffer (6.06g of Tris-Base, 28g glycine, 0.2g SDS, 1600 ml dH2O, 400 ml MeOH). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in 1X TBS-T for 1 hour. Primary antibodies were incubated with membranes overnight at 4° C at 1:1000 dilution in 5% milk in 1X TBS-T and appropriate secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with membranes at 1:10000 dilution in 5% milk in 1X TBS-T. Membranes were washed 3X10 minutes before and after secondary antibody incubation in 1X TBS-T. West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific Waltham, MA) was used to visualize the protein antibody complexes. Primary antibodies included 2-PDCD-4 antibodies (ProSci, Poway, CA and Sigma, St.Louis, MO), actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-EF2, and cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Secondary antibody used for all westerns other than actin was donkey anti-Rabbit IgG-HRP (GE Healthcare, Little Chalftont, UK.). Secondary antibody used for the Actin westerns was donkey anti-Goat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA.)

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (250ng) was reverse transcribed using the miScript Reverse Transcription Kit per the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Samples were diluted 1:10 in dH20 for qRT-PCR, which was performed on an Applied Biosystems HT7900 sequence detector (Foster City, CA). Primer sets for U6 (forward primer CTC GCT TCG GCA GCA CA, reverse primer AAC GCT TCA CGA ATT TGC GT) and PDCD-4 (forward primer GGC CCG AGG GAT TCT GAA, reverse primer TAT CTG CTC ATT TTC TAC ATC CAT TTT) and the forward primer for miR-21 (TAG CTT ATC AGA CTG AT) were designed using Primer Express 3.0 Software. A universal primer from the miScript Sybr green PCR Kit (Qiagen) along with its forward primer was used to amplify miR-21. Samples were run in triplicates and the ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the relative fold change between the samples following normalization with U6 (20). The presence of a single dissociation curve confirmed the amplification of a single transcript and lack of primer dimers. Standard RT-PCR using primers (forward primer GAAAATGCTGGGACTGAGGAA, reverse primer GACGACCTCCATCTCCTTCGCT) designed to span the complete PDCD-4 coding sequence was completed to determine if alternative spliced variants exist.

Statistics

Band intensity of each protein was determined using Gel-Pro Analyzer software. The mean amount (n=3) of each protein was determined by normalizing the intensity of the specific protein bands to that of actin. The mean value of each samples’ triplicate in qRT-PCR was normalized to U6 using the ΔΔCt method as described previously (20). Student's T-tests were performed to determine if expression levels of protein and/or mRNA of interest was affected by treatment. Statistical significance was considered at P<0.05.

Results

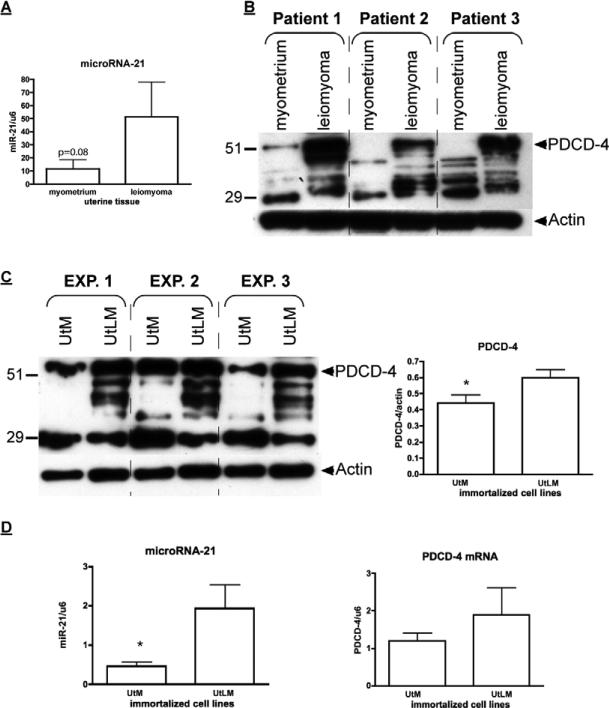

Consistent with elevated miR-21 in leiomyomas in previous studies, mature miR-21 levels in our leiomyoma tissues trended towards a 3.9 ± 2.9-fold increase (P=0.08) compared to normal myometrium (Figure 1A). Expression of PDCD-4 mRNA in leiomyoma (4.2 ± 0.8; mean fold ± SEM) and myometrial (3.9 ± 1.1) tissues were not different (P=0.85). In contrast, full-length 51 kDa PDCD-4 protein levels were markedly different in paired leiomyoma and myometrial tissues with myometrium showing barely detectable levels while leiomyoma tissues exhibited a robust signal (Figure 1B). No differences in PDCD-4 or miR-21 by stage of menstrual cycle were noted. Conversely, the paired myometrial tissues exhibited a lower molecular weight immunoreactive band that was not evident in the leiomyoma tissues (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1A). To ensure this lower band was not an artifact, another PDCD-4 antibody (Sigma) was used (see Supplementary Figure 1B) and a similar pattern of immunoreactive bands was present, albeit the signal was not as robust for the lower band in the myometrium. In addition, leiomyomas exhibited a number of additional immunoreactive bands below the predicted full length 51 kDa PDCD-4 again with both antibodies. .

Figure 1.

Differential expression of PDCD-4 and miR-21 in leiomyoma and myometrial tissues and immortalized cell lines, UtLM (leiomyoma) and UtM (myometrial). A) Western analysis of PDCD-4 isoforms in 3 representative paired leiomyoma and normal myometrial samples of a total of 11 examined are shown. B) Western analysis of PDCD-4 isoforms in UtLM and UtM cell lines. *Means ± SEM (n=3) for the 51 kDa band between cells types are different (P<0.05). C) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-21 and PDCD-4 mRNA levels in UtLM and UtM cell lines. *Means ± SEM (n=3) are different (P<0.05) between UtLM cells and UtM cells.

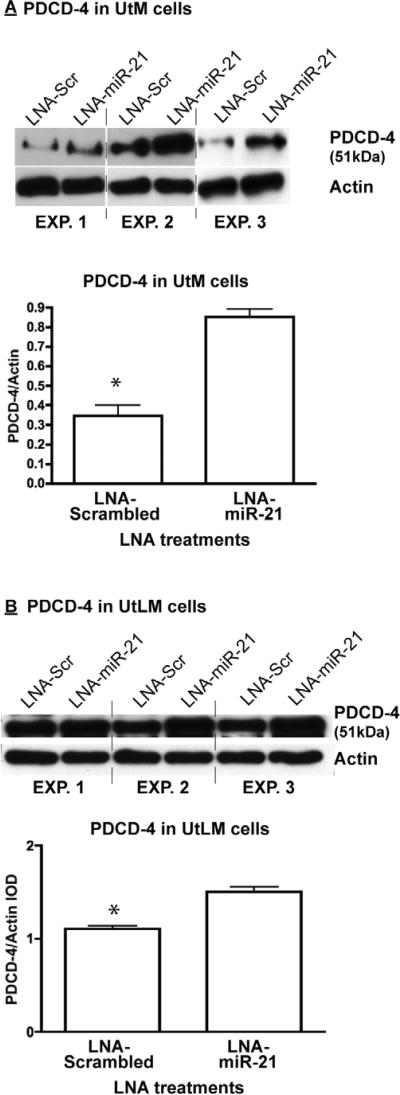

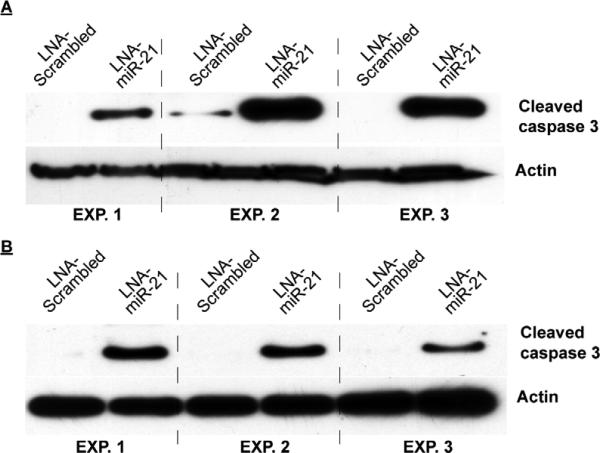

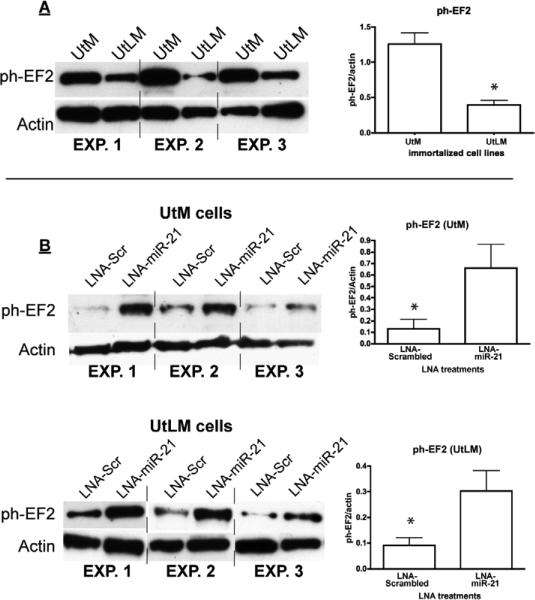

Immortalized myometrial cells (UtM) and leiomyoma cells (UtLM) were assayed for their relative expression of PDCD-4 mRNA/protein and miR-21. Unlike myometrial and leiomyoma tissues obtained from patients, both cell lines expressed the 51 kDa isoform, but consistent with the tissues, the UtLM cells had higher levels (1.4-fold) than UtM cells. Again consistent with tissues, the lower molecular wt immunoreactive band was higher (2-fold) in UtM cells (Figure 1C). In addition, similar to patient-derived leiomyomas, a number of immunoreactive bands between 50 and 32 kDa were observed in the UtLM cells with minor evidence of these intermediate bands in the UtM cells. RT-PCR for the full length mRNA failed to show differences between the myometrial and leiomyoma tissues. Direct comparison of PDCD-4 protein expression between tissue samples and immortalized cell lines revealed that the expression pattern of the normal myometrial tissues closely resembles that of the UtM cells while that of the leiomyoma tissues closely resembles that of the UtLM cells. PDCD-4 mRNA expression did not differ significantly between the cell lines (Figure 1D), while mature miR-21 expression was 4-fold greater in UtLM cells compared to UtM cells (Figure 1D). Since PDCD-4 is a known functional target of miR-21 in other cell lines, we analyzed PDCD-4 expression after inhibition of miR-21 in both the UtM and UtLM cell lines (Supplementary Figure 2A confirms the loss of mature miR-21 levels following LNA-miR-21 treatment of UtM and UtLM cells). Inhibition of miR-21 in UtM cells increased expression of the 51 kDa PDCD-4 isoform 2.5-fold (Figure 2A), whereas inhibition of miR-21 in UtLM cells increased the expression of the 51 kDa PDCD-4 isoform only 1.5-fold (Figure 2B). While loss of miR-21 action following LNA-miR-21 treatment impacted PDCD-4 protein synthesis, we observed no effect on PDCD-4 mRNA expression in either UtM or UtLM cells (Supplementary Figure 2B). Consistent with miR-21's anti-apoptotic activity, inhibition of miR-21 activity increased the level of cleaved caspase-3, a marker of apoptosis in both UtM and UtLM cells (Figure 3A and B). In addition to its effects on PDCD-4 and apoptosis, we also examined whether miR-21 could affect global protein translation by measuring a key regulatory step, the phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 (EF2), a protein critical for protein translation (21). Increased levels of phosphorylated EF-2 in myometrial cells compared to the leiomyoma cells (Figure 4A) would be consistent with greater overall protein expression by the leiomyoma cells. Inhibition of miR-21 in UtM and UtLM cell lines caused a 6-fold and 3-fold induction of phosphorylated EF-2, respectively, indicating that miR-21 expression can positively affect translation in both cell lines (Figure 4B).

Figure 2.

miR-21 regulation of PDCD-4 in UtM and UtLM cells. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides complementary to miR-21 (LNA-miR-21) or a scrambled (LNA-scr) control were transfected into UtM cells (A) or UtLM cells (B). *Means ± SEM (n=3) PDCD-4 (51 kDa isoform) levels normalized to actin are different (P<0.05) between LNA-scramble and LNA-miR-21 treated cells.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of miR-21 in UtM and UtLM cells increases cleaved caspase-3. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides complementary to miR-21 (LNA-miR-21) or a scrambled (LNA-scramble) control were transfected into UtM cells (A) or UtLM cells (B). Western analysis showed a significant induction of cleaved caspase-3 in the LNA-miR-21 treated UtM and UtLM cells across 3 independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Expression of phosphorylated EF-2 in UtM and UtLM cells following knockdown of miR-21. A) Basal ph-EF2 expression levels in UtM cells and UtLM cells. *Means ± SEM (n=3) ph-EF2 levels normalized to actin are different (P<0.05). B) Locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides complementary to miR-21 (LNA-miR-21) or a scrambled (LNA-scr) control were transfected into UtM cells or UtLM cells. *Means ± SEM (n=3) ph-EF2 levels normalized to actin are different (P<0.05) between LNA-scramble and LNA-miR-21 treated cells.

Discussion

As part of our examination of miR-21's role in uterine fibroid pathophysiology, we uncovered that PDCD-4, a potential target of miR-21, exhibited a dramatic increase in protein expression in leiomyoma tissues compared to autologous myometrial tissues, with no corresponding change in mRNA levels. Our results also revealed that the pattern of PDCD-4 expression, as well as that of miR-21 were preserved in immortalized myometrial and leiomyoma cells, enabling us to investigate miR-21's potential role in regulating PDCD-4 protein levels. Using these cells we demonstrated that miR-21 down regulates PDCD-4 protein expression. However, this is likely a minor effect because even though levels of miR-21 were elevated in leiomyoma tissues (our findings and others 9-11), the expression of PDCD-4 protein in leiomyomas was increased as well. We further demonstrated that miR-21 is able to exert independent effects in myometrial/leiomyoma cells (i.e., increased cell growth and blockade of apoptosis) that are consistent with the pathophysiology of this disease.

Loss of PDCD-4 is associated with tumor progression and PDCD-4 reintroduction into cells can block neoplastic growth (22). Based on these studies we were surprised to detect increased expression of PDCD-4 protein in leiomyoma tissues in our study, particularly, because we expected the elevated levels of miR-21 to decrease protein levels by blocking mRNA translation. Recent studies indicate that PDCD-4 exhibits decreased expression in metastatic tumors in humans and mice and that restoring expression blocks the metastatic (invasive) potential of tumor cells (13, 22). Thus, our unexpected finding of highly elevated PDCD-4 protein in leiomyomas raises the possibility that its role in these benign tumors may be to prevent malignant progression. Perhaps loss of PDCD-4 may occur in metastasizing leiomyomas or in leiomyosarcomas. What drives the increased PDCD-4 protein expression in leiomyomas remains unknown. While our study indicated that this was not likely a transcriptional response (i.e., equivalent PDCD-4 mRNA in leiomyoma and myometrial tissues), a large expression analysis study (23) of paired human uterine leiomyoma and myometrial tissue was able to show a slight 1.32-fold (P<0.05) increase in PDCD-4 mRNA levels in leiomyoma over myometrial tissues (GSE13319). This slight increase in PDCD-4 mRNA expression, however, does not explain the marked differences in protein levels we observed.

Functional studies of the 51 kDa PDCD-4 have revealed that it can inhibit cap dependent translation as well as regulate RNA metabolism (24). We were unable to find reported evidence of the low molecular weight band observed in myometrial tissues in any other tissues. We also observed that leiomyoma tissue and immortalized-leiomyoma cells exhibited the presence of numerous immunoreactive bands below the full length 51 kDA isoform. These may be the result of alternative splicing or proteasomal degradation in leiomyoma tissues. Recently, Schmid et al., (25) proposed that proteosomal degradation of PDCD-4 requiring activation of the mTOR pathway is involved in inflammation-mediated tumor progression. The exact nature of these immunoreactive products (alternative spliced protein, degradation product) remains to be determined, yet our simple RT-PCR analysis was unable to detect different mRNA isoforms. Determination of the PDCD-4 isoform composition within biopsies may have clinical value for characterization of the metastatic potential of leiomyomas.

The combined differential expression of miR-21 and PDCD-4 protein in the UtLM (leiomyoma) cells compared to UtM (myometrial) cells in a manner consistent with the expression in autologous pairs of primary tissues indicates that these cell lines are a useful model system for studying miR-21 and PDCD-4 expression and their potential interactions. Previous investigations have revealed that miR-21 post-transcriptionally regulates PDCD-4 in a number of cancer cell lines, including MCF-7, Colo206f and MDA-MB-231 (26-28). Inhibition of miR-21 in both UtLM and UtM cells increased expression of the 51 kDa isoform of PDCD-4 protein, while having no effect on the lower immunoreactive molecular weight band. The lack of change in PDCD-4 mRNA levels indicates that miR-21 post-transcriptionally regulates PDCD-4 primarily through a block of translation and not mRNA degradation. The PDCD-4 mRNA results of our study, contrast those of Pan et al (17), who showed that inhibition and overexpression of miR-21 in several uterine smooth muscle cell lines could impact PDCD-4 mRNA levels. Possible differences in experimental systems (i.e., cell lines or type of inhibitors used) may account for these differences, yet our results from the UtM-immortalized cells are consistent with our tissue-derived data. Inhibition of miR-21 resulted in reduced induction of PDCD-4 protein in UtLM cells compared to UtM cells, possibly due to the higher initial basal levels of PDCD-4 in UtLM cells or because miR-21 levels may have less regulatory impact in UtM cells. The higher basal expression levels of miR-21 in UtLM cells may also explain why inhibition of PDCD-4 with a fixed amount (albeit a saturating amount) of the blocking LNA-miR-21 was less effective. Thus, while showing for the first time that miR-21 can modulate PDCD-4 protein levels in leiomyoma cells in culture, our experiments suggest that miR-21 is in of itself, not a potent regulator of PDCD-4 expression in leiomyoma tissues as the levels of PDCD-4 should have decreased in leiomyoma tissues rather than increased.

Earlier array studies revealed that miR-21 has higher expression levels in leiomyomas when compared to normal myometrium (9-11). Our study supports these previous observations, although the 3.9-fold induction we observed only trended toward significance (P=0.08). This discrepancy could be a result of our smaller sample sizes (n=12) compared to the larger sample sizes (n>50) used in previous studies where miR-21 was identified as upregulated. Significantly, the higher expression of miR-21 in leiomyoma tissues was consistent with the findings of in vitro cell culture results that showed elevated miR-21 expression levels in UtLM cells. This increased level of expression of miR-21 in leiomyoma tissues may provide limited regulatory control of PDCD-4 expression in vivo as compared to the greater regulation seen in our in vitro results. Since miR-21 overexpression in leiomyoma tissues and immortalized leiomyoma cells did not have a major impact on PDCD-4 expression, we also examined whether it might be influencing other cellular processes that had previously been reported (29-31). Studies have shown increased expression of Bcl-2, a cell survival gene, and TNFα, a gene known to induce apoptosis in leiomyomas compared to normal myometrium (32). Wu et al., found that there was no difference between the apoptotic index of leiomyoma and myometrial tissues (33), suggesting that Bcl-2, TNFα as well as other yet-to-be identified proteins (factors) are functioning to maintain homeostatic relationship in leiomyoma tissues. Our study sought to determine whether miR-21, an oncomir known to inhibit apoptosis, might play a role in regulation of apoptosis in UtLM and/or UtM cells. Knockdown of miR-21 caused a robust increase in cleavage of caspase 3, a marker for programmed cell death, in both cell lines. This finding indicates that elevated levels of miR-21 may act to prevent programmed cell death in rapidly growing leiomyomas. It is possible that miR-21 contributes to this apoptotic homeostatic balance through indirect regulation of Bcl-2 and/or TNFα. Further studies are needed to determine if these genes may be direct or indirect targets of miR-21, or whether miR-21 impacts other apoptotic genes.

Previous investigations have also shown increased PCNA and Ki67 staining in leiomyomas over that of normal myometrium, indicating that leiomyoma is a more highly proliferative tissue (33-35). Studies have also implicated the involvement of the mTOR pathway in the development of leiomyomas. Makker et al., (36) showed that mTOR signaling is increased in leiomyomas, while Yin et al. (37), revealed that estrogen requires mTOR to drive G1 cell cycle progression in leiomyomas. Elongation factor 2 (EF2), a gene that functions in protein synthesis and a downstream mediator of the mTOR pathway, is involved in control of global translation. In its un-phosphorylated form, EF2 is able to bind to the ribosome and translocate the mRNA-tRNA complex from the A site to the P site, and thus promote translation (24, 38). Our study revealed that inhibition of miR-21 in both UtLM and UtM cells increased phosphorylation levels of EF2, supporting the hypothesis that basal levels of miR-21 in both cell lines are critical for maintaining EF2 in its un-phosphorylated state thereby allowing increased translation. These findings indicate that miR-21 may promote cell proliferation/growth through regulation of upstream mediators of EF2 phosphorylation.

Overall, the findings from our studies indicate that PDCD-4 exhibits a unique expression profile ,with almost complete absence of the full length PDCD-4 protein in normal myometrium, combined with unexpected, high overexpression in leiomyomas. This would suggest that PDCD-4 does not act as a typical tumor suppressor gene in leiomyomas as has been shown for several malignant tumors. Future studies, examining the role that steroids and other key regulatory molecules play in the regulation of PDCD-4 expression may prove to be highly informative. Additionally, a possible beneficial role in maintaining leiomyomas as benign non-metastatic tumors can be envisioned based on previous studies. Our studies also demonstrated that while the elevated levels of miR-21 found in leiomyoma tissues had a limited effect on PDCD-4 expression; it may yet play key roles in promoting translation to stimulate growth of the leiomyoma cells. Lastly, the similar patterns of expression of miR-21 and PDCD-4 between the immortalized cell lines and in vivo tissues, supports the concept that UtLM and UtM cells are useful model systems for studying miR-21 and PDCD-4 function and regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors convey special thanks to Binny Varghese for technical support.

Grant support: This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD061580; LKC and PO1HD057877; RAN).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

J.B.F., V.C., F.K., R.A.N. and L.K.C. have nothing to disclose.

Capsule

PDCD-4 is unexpectedly elevated in leiomyomas, while normal myometrium does not express the protein. The expected inverse correlation of microRNA-21 and its target, PDCD-4 is absent in fibroids.

References

- 1.Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence* 1. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:100–7. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farquhar CM, Steiner CA. Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990–1997. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2002;99:229. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandon D, Bethea C, Strawn E, Novy M, Burry K, Harrington M, et al. Progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein are overexpressed in human uterine leiomyomas. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169:78–85. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart EA, Friedman AJ. Steroidal treatment of myomas: preoperative and long-term medical therapy. Thieme. 1992:344–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato F, Mori M, NISHI M, Kudo R, Miyake H. Familial aggregation of uterine myomas in Japanese women. Journal of epidemiology. 2002;12:249–53. doi: 10.2188/jea.12.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luoto R, Kaprio J, Rutanen EM, Taipale P, Perola M, Koskenvuo M. Heritability and risk factors of uterine fibroids--the Finnish Twin Cohort study. Maturitas. 2000;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs—microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6:259. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsh EE, Lin Z, Yin P, Milad M, Chakravarti D, Bulun SE. Differential expression of microRNA species in human uterine leiomyoma versus normal myometrium. Fertility and sterility. 2008;89:1771–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Q, Luo X, Chegini N. In Focus: Differential expression of microRNAs in myometrium and leiomyomas and regulation by ovarian steroids. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2008;12:227–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Wang T, Zhang X, Obijuru L, Laser J, Aris V, Lee P, et al. A micro RNA signature associated with race, tumor size, and target gene activity in human uterine leiomyomas. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 2007;46:336–47. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel LB, Christoffersen NR, Jacobsen A, Lindow M, Krogh A, Lund AH. Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:1026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lankat-Buttgereit B, Goke R. The tumour suppressor Pdcd4: recent advances in the elucidation of function and regulation. Biology of the Cell. 2009;101:309–17. doi: 10.1042/BC20080191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lankat-Buttgereit B, Gregel C, Knolle A, Hasilik A, Arnold R, Goke R. Pdcd4 inhibits growth of tumor cells by suppression of carbonic anhydrase type II. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2004;214:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen AP, Camalier CE, Colburn NH. Epidermal expression of the translation inhibitor programmed cell death 4 suppresses tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 2005;65:6034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei N, Liu SS, Chan KKL, Ngan HYS. Tumour Suppressive Function and Modulation of Programmed Cell Death 4 (PDCD4) in Ovarian Cancer. PloS one. 2012;7:e30311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan Q, Luo X, Chegini N. microRNA 21: response to hormonal therapies and regulatory function in leiomyoma, transformed leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma cells. Molecular human reproduction. 2010;16:215–27. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Grudzien MM, Low PS, Manning PC, Arredondo M, Belton RJ, Nowak RA. The antifibrotic drug halofuginone inhibits proliferation and collagen production by human leiomyoma and myometrial smooth muscle cells. Fertility and sterility. 2010;93:1290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Condon J, Yin S, Mayhew B, Word R, Wright W, Shay J, et al. Telomerase immortalization of human myometrial cells. Biology of reproduction. 2002;67:506. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiedler SD, Carletti MZ, Christenson LK. Quantitative RT-PCR methods for mature microRNA expression analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;630:49–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-629-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryazanov AG, Davydova EK. Mechanism of elongation factor 2 (EF-2) inactivation upon phosphorylation Phosphorylated EF-2 is unable to catalyze translocation. FEBS letters. 1989;251:187–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young MR, Santhanam AN, Yoshikawa N, Colburn NH. Have Tumor Suppressor PDCD4 and its Counteragent Oncogenic miR-21 Gone Rogue? Molecular Interventions. 2010;10:76. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crabtree JS, Jelinsky SA, Harris HA, Choe SE, Cotreau MM, Kimberland ML, et al. Comparison of human and rat uterine leiomyomata: identification of a dysregulated mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Cancer research. 2009;69:6171. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang HS, Jansen AP, Komar AA, Zheng X, Merrick WC, Costes S, et al. The transformation suppressor Pdcd4 is a novel eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A binding protein that inhibits translation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:26. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.26-37.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid T, Bajer MM, Blees JS, Eifler LK, Milke L, Rübsamen D, et al. Inflammation-induced loss of Pdcd4 is mediated by phosphorylation-dependent degradation. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1427–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allgayer H. Pdcd4, a colon cancer prognostic that is regulated by a microRNA. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2010;73:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Z, Liu M, Stribinskis V, Klinge C, Ramos K, Colburn N, et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes cell transformation by targeting the programmed cell death 4 gene. Oncogene. 2008;27:4373–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asangani I, Rasheed S, Nikolova D, Leupold J, Colburn N, Post S, et al. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2007;27:2128–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Si M, Zhu S, Wu H, Lu Z, Wu F, Mo Y. miR-21-mediated tumor growth. ONCOGENE- BASINGSTOKE- 2007;26:2799. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, Ji R, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, et al. MicroRNAs are aberrantly expressed in hypertrophic heart: do they play a role in cardiac hypertrophy? The American journal of pathology. 2007;170:1831. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu S, Wu H, Wu F, Nie D, Sheng S, Mo YY. MicroRNA-21 targets tumor suppressor genes in invasion and metastasis. Cell research. 2008;18:350–9. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurachi O, Matsuo H, Samoto T, Maruo T. Tumor necrosis factor-α expression in human uterine leiomyoma and its down-regulation by progesterone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86:2275. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Blanck A, Olovsson M, Möller B, Favini R, Lindblom B. Apoptosis, cellular proliferation and expression of p53 in human uterine leiomyomas and myometrium during the menstrual cycle and after menopause. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruo T, Matsuo H, Samoto T, Shimomura Y, Kurachi O, Gao Z, et al. Effects of progesterone on uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis. Steroids. 2000;65:585–92. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maruo T, Ohara N, Wang J, Matsuo H. Sex steroidal regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth and apoptosis. Human reproduction update. 2004;10:207–20. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makker A, Goel MM, Das V, Agarwal A. PI3K-Akt-mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways in polycystic ovarian syndrome, uterine leiomyomas and endometriosis: an update. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2011:1–7. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2011.583955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin XJ, Wang G, Khan-Dawood FS. Requirements of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin for estrogen-induced proliferation in uterine leiomyoma-and myometrium-derived cell lines. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;196:176, e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryazanov AG, Shestakova EA, Natapov PG. Phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 by EF-2 kinase affects rate of translation. 1988 doi: 10.1038/334170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.