Acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (AHI) is brief in duration, results in mild clinical illness, and is rarely diagnosed.1–3 This phase of infection usually lasts about two to three months, and the symptoms, if any, may include fever, fatigue, and rash.1 However, few people are diagnosed during this phase, as acute infection is relatively brief and occurs prior to the production of detectable HIV antibodies. Nonetheless, this phase has great significance to public health, being one of the most infectious phases of HIV infection and marking the beginning of a chronic, communicable infection and disease that is usually diagnosed only after a clinically silent, lengthy interval.4 The potential for AHI to contribute to HIV transmission has been documented by public health officials in the United States,5 and published statistical models suggest that individuals in the acute phase of HIV contribute disproportionately to sustaining the HIV epidemic.6–8

While AHI has been recognized as a critical time to inform patients of the need to reduce risk behaviors and perform partner elicitation, notification, and testing services,9–11 it seems likely to take on additional significance for treatment initiation as an approach to prevention. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is increasingly seen as a means for population-wide HIV prevention.3 This approach to prevention, also known as the test-and-treat strategy, relies upon early identification of HIV infection followed by prompt initiation of ART to achieve the maximum possible viral suppression during the patient's lifetime with HIV.12 The test-and-treat strategy is gaining attention, and its feasibility is being tested in major U.S. cities.13,14

The magnitude of AHI's public health significance is matched by the difficulty entailed in its detection. The diagnostic challenge posed by AHI has inspired screening efforts involving complex and expensive laboratory procedures using pooled nucleic acid amplification test (pNAAT) algorithms.5,15,16 Programs designed to increase the ascertainment of AHI by pNAAT have been conducted and described in North Carolina,5,17 Seattle (Washington),18 Los Angeles (California),19 San Francisco (California),20 and New York City (NYC).21 While effective in increasing the detection of AHI, such pNAAT programs are costly, and targeting their use to the highest-yield populations to maximize efficiency has been recommended.19,22,23 In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a fourth-generation antigen (Ag)/antibody (Ab) HIV diagnostic test that is expected to make AHI screening more efficient and less expensive. Several jurisdictions, including NYC, are being funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to evaluate the new test's ability to detect AHI compared with pNAAT. As AHI screening efforts grow in variety and scope, there will be a burgeoning need to evaluate their population impact on AHI detection.

AHI's relevance to HIV prevention efforts, and the scale and expense of programs designed to increase its detection, suggest that routine monitoring of the frequency with which AHI diagnoses are made among the larger number of newly diagnosed HIV case patients would be useful. However, despite its public health importance, AHI has not been a part of routine HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) surveillance in the U.S.

Starting in 2008, the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) made detection of AHI part of routine surveillance of HIV/AIDS in NYC.21 To our knowledge, NYC is the first jurisdiction to incorporate population-based, systematic tracking of AHI into routine HIV/AIDS surveillance, and we expect that other cities will follow as the technology for easier detection of AHI gains wider use. In this article, we build upon previously reported findings21 by (1) describing the process of implementing AHI surveillance in NYC in greater depth, including refinements to our system introduced since its initial description; and (2) summarizing the first two years of NYC AHI surveillance data.

METHODS

Establishing an AHI case definition

We built on CDC's adult HIV case definition24 so that AHI cases are a subset of all new HIV diagnoses for those aged 13 years and older. The NYC DOHMH case definition for AHI includes people with a negative or indeterminate HIV Ab test with a detectable HIV viral load (VL) result (>5,000 copies/milliliter [mL]), a negative or indeterminate HIV Ab test followed by a positive Ab test, or a physician diagnosis of AHI.21 The threshold of 5,000 copies/mL was used to exclude potential false-positive results among individuals with a negative or indeterminate HIV Ab test. Our goal was to use laboratory criteria25 to define AHI whenever possible; however, we also wanted to incorporate the clinical judgment involved in diagnosing AHI into our case definition. To maximize case finding, we allowed for a documented clinical diagnosis of AHI to meet the definition on that criterion alone. To understand providers' AHI diagnostic habits, we began collecting data on whether AHI cases met our definition on the basis of clinical criteria, laboratory criteria, or both. We calculated the HIV diagnosis date as the earliest among the following dates as documented in the patient's chart: indeterminate (followed up with either a detectable VL or positive Western blot [WB] test result) or positive WB test, first detectable VL, or physician diagnosis.

Case identification

AHI case identification was incorporated into existing protocols for routine HIV/AIDS case finding, which relies primarily on mandated reporting of HIV-related events by providers and laboratories to New York State (NYS). The largest source of reports of new diagnoses is laboratory reporting, which in NYS has included all positive WB tests for HIV Ab, all VL and cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) values, and all HIV genotype tests since 2005.26–28 Existing protocols for case finding and confirmation prompted by reportable laboratory events are built around the matching of reportable laboratory events to NYC's population-based HIV Surveillance Registry of all reported cases of AIDS since 1981 and HIV since 2000. Incoming positive WB tests, detectable and serial undetectable VL test values, and AIDS-defining CD4 results that do not match to the HIV Surveillance Registry prompt a field investigation involving medical record review by surveillance staff to verify and collect laboratory test results, demographic and transmission risk information, and other relevant case details. Provider reports of new cases also prompt a field investigation and medical record review to ensure accurate data collection. Finally, active surveillance at several large-volume diagnosing providers by field services staff responsible for delivering HIV partner services also generates new cases.

Starting in June 2009, case records with a VL test value of ≥ 100,000 copies/mL and no associated positive WB test received on or before the VL test date were flagged as possible AHI on forms sent for field investigation. Field staff were told that possible AHI should prompt them to verify AHI status during their medical record review.

Staff training and modification of data collection forms

To promote increased identification of cases diagnosed in the acute stage, we trained all field staff and modified case investigation forms. Trainings were incorporated into regularly scheduled, hour-long, biweekly meeting timeslots with all field staff. Senior staff trained field personnel in January 2008, reviewing how to recognize possible AHI during chart review from a range of scenarios, prior to the introduction of an acute/non-acute variable on the data collection form. Staff were trained to recognize combinations of negative/indeterminate Ab tests and high VL test results, and to record the AHI status of every new HIV diagnosis on the modified case investigation form (e.g., AHI/primary HIV infection at diagnosis? Yes/no/unknown). Staff were also trained to record a documented provider diagnosis of AHI and to record available patient HIV testing history information. Trainings were also provided to field services staff, who are assigned to high-prevalence facilities in NYC for active case finding. These staff and surveillance staff informed medical reviewers of cases with combinations of laboratory tests suggestive of AHI.

Provider outreach

Both the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control and the Bureau of Sexually Transmitted Disease Control (BSTDC) worked to promote greater provider understanding of and vigilance with regard to AHI. In February 2009, BSTDC sent a Health Alert to health professionals in NYC, including physicians, nurses, and social workers, describing reported characteristics of AHI cases ascertained through the pNAAT program and urging providers to evaluate potential cases.29 The Health Alert Network reaches about 20,000 external e-mail recipients from health-related fields. The director of HIV/AIDS Surveillance wrote a letter to NYC providers in June 2009 similarly promoting provider awareness of the clinical features of AHI and the public health importance of diagnosing infections during the acute stage. The letter also encouraged providers to clearly document AHI in the medical chart.30 DOHMH field staff gave physicians at surveillance facilities a folder containing the letter, an NYS provider report form, and two condoms with the NYC logo.

Intra-agency collaboration

The HIV surveillance unit coordinated with staff managing the pNAAT screening program in DOHMH-run sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics. Under this program, which was launched in May 2008, confidential, blood-based samples testing Ab-negative were submitted for pNAAT. Samples testing positive on pNAAT are confirmed by WB test or individual VL if >5,000 copies/mL, and BSTDC staff perform follow-up interviews, linkage to care, and partner notification.21 BSTDC reports AHI cases detected through pNAAT to the HIV surveillance unit for timely inclusion in the HIV Surveillance Registry.

Data cleaning and management

We also integrated AHI surveillance into our standard quality assurance procedures for data collection, the core of which is a biweekly scan of the field investigation database for any completed field investigation forms with a missing AHI designation at diagnosis. Public health advisors were provided feedback as to completion rates of this variable to encourage full implementation of the new procedure. AHI can be misidentified as an unconfirmed HIV case because there are frequently negative HIV Ab results, prompting our medical reviewer to query the database for unconfirmed cases with high VL test results.

Given the time-sensitive nature of AHI surveillance, we had to adjust our standard data flow for timely review and analysis of AHI cases. Biweekly database scans were incorporated as an additional case-finding tool for AHI; these scans included a line list of field investigations from the previous two weeks in which an AHI diagnosis was recorded, and this line list was provided to a medical reviewer to ensure timely and correct assignment of AHI status. All cases confirmed by the medical reviewer to be AHI within three months of their HIV diagnosis date were referred to the HIV field services unit (FSU) as a case in the acute stage. FSU staff would interview the case and assist in care linkage and partner notification at non-BSTDC sites.31

Because of the lag between first report of possible AHI to NYC DOHMH and entry into the HIV Surveillance Registry, we created a separate database of AHI cases populated by data from the multiple sources of AHI case finding, including the reportable laboratory events database, field investigation database, provider reporting, and patient interviews. We regularly de-duplicated AHI records across these sources by name and date of birth. The AHI database was created in house by our information technology support unit within a few months. The database uses a structured query language database with table views from a Web-based interface housing other surveillance databases. Prior to the availability of the database, we tracked cases using spreadsheets and imported data into SAS® for routine analyses.32

Data analyses

Data on AHI cases diagnosed from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2009, and reported to NYC DOHMH by September 30, 2010, are included. Data from all available sources were used to classify patient's sex, race/ethnicity, age at time of diagnosis, transmission risk, and NYC borough of residence.

We present comparisons of demographic characteristics among AHI cases diagnosed in 2008 and 2009. Transmission risk categories included men who have sex with men (MSM), injection drug use (IDU) history, MSM and IDU, heterosexual transmission, other, and no risk reported (unknown). We employed standard CDC risk categorization for all but the heterosexual transmission category, which expands to include probable heterosexual risk.33 Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for small cells were used for comparisons, and all tests were two-sided at α =0.05. We used SAS® version 9.1.3 for statistical analyses.32

RESULTS

Capacity for ascertaining AHI cases

From January 1, 2008, to September 30, 2010, 21 surveillance staff conducted 33,027 field investigations at 1,890 providers and facilities in NYC. Seven staff supervised field staff and reviewed completed field investigation forms, and four nonmedical surveillance administrators assigned, reviewed, and processed case investigations. Among the 33,027 field investigations, about 6,689 (20.3%) were prompted by a detectable VL, of which 1,245 (18.6%) were VL ≥ 100,000 copies/mL. Approximately 20 partner services staff conducted 3,482 interviews and detected 172 new cases through active surveillance.

Case identification

Process of case identification.

In total, 193 AHI cases were identified by surveillance and FSU staff. Of these, 112 (58.0%) cases met the case definition on the basis of laboratory criteria and physician diagnosis (Figure). Most cases (n=134, 69.4%) met the AHI case definition on the basis of a negative or indeterminate HIV Ab test with a detectable VL result, with 22 of these cases also having a prior negative or indeterminate HIV Ab test within three months preceding diagnosis. A total of 46 (23.8%) cases met the definition through these latter criteria, and 35 cases (18.1%) met the definition with provider diagnosis only.

Figure.

Flow chart of total NYC acute HIV infection cases diagnosed in 2008–2009, by case definition criteria

NYC = New York City

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AHI = acute HIV infection

VL = viral load

pNAAT screening identified 46 (23.8%) cases overall. Two cases were found retrospectively through the medical reviewer's scan of the field investigation database of individuals assigned unconfirmed case status with later high VL results. The possible AHI flag was marked on 32 forms for AHI cases; 28 (87.5%) had an accompanying provider diagnosis of AHI recorded in the chart, but four (12.5%) did not (data not shown).

During 2008–2009, more than 1,103 distinct providers and facilities citywide reported 7,673 newly diagnosed adult and adolescent cases of HIV. Of these, 81 providers—including seven DOHMH STD clinics conducting pNAAT screening, 22 hospitals, 50 freestanding and university clinics, one correctional facility, and one clinical trial—diagnosed at least one AHI case (data not shown).

Description of confirmed AHI cases

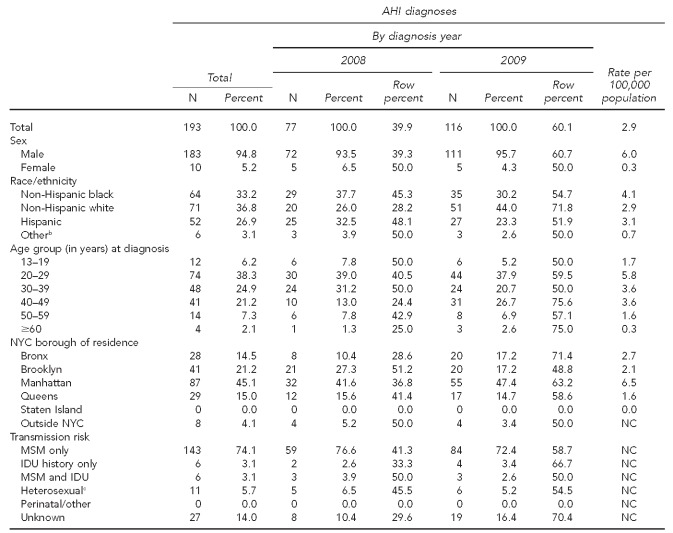

By September 2010, a total of 193 cases diagnosed during 2008–2009 were detected in the acute stage of HIV infection (Table). AHI cases were a median age of 32.0 years (range: 15–68 years) at the time of diagnosis (data not shown), and the vast majority of cases (94.8%) were male. More than three-quarters (n=149, 77.2%) of AHI cases reported MSM-only or combined MSM and IDU risk.

Table.

Total acute HIV infection diagnoses among adolescents and adults aged 13 years and older in NYC, 2008–2009a

aBased on data reported to the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene by September 30, 2010. Rates are based on population from the 2000 U.S. Census. Rates based on numerators ≤ 10 should be interpreted with caution.

bOther race/ethnicity includes Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, and multiracial.

cIncludes people who had heterosexual sex with an HIV-infected person, an injection drug user, or a person who has received blood products. For females only, also includes history of prostitution, multiple sex partners, sexually transmitted disease, crack/cocaine use, sex with a bisexual male, probable heterosexual transmission as noted in medical chart, or sex with a male and negative history of IDU.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NYC = New York City

AHI = acute HIV infection

NC = not calculable

MSM = men who have sex with men

IDU = injection drug use

From 2008 (n=77) to 2009 (n=116), the number of AHI cases overall increased 50.6%. However, the increase was only observed among males; five females were diagnosed during each year. Cases' risk distribution was similar in 2008 and 2009, with most cases having MSM-only risk. There were no statistically significant demographic differences between cases diagnosed in 2008 vs. 2009.

DISCUSSION

NYC DOHMH successfully incorporated AHI detection into routine HIV surveillance beginning in 2008. As laboratory tests capable of distinguishing AHI from longer-standing HIV infections become more efficient and available (i.e., HIV Ag-Ab combo assay), and as initiatives to increase HIV testing begin to have their intended effect of diagnosing HIV earlier in its course, we think it should be more feasible for other jurisdictions to engage in similar efforts to conduct AHI surveillance.

Based on our experience, we have identified the following conditions as key to the successful implementation of AHI surveillance: (1) full range of reportable HIV-related laboratory results (i.e., positive WB tests, all VL tests, all CD4 tests, and all viral nucleotide sequence results); (2) electronic laboratory reporting for more timely report and ease of processing the high volume of reportable results; (3) close relationship with STD clinics and other facilities performing AHI screening through pNAAT or other means; (4) close integration between surveillance staff and active surveillance at the highest-volume HIV clinics; (5) sophisticated information technology and analytic infrastructure, especially skilled data management and programming staff; and (6) staffing, especially doctors, to train data collectors and conduct outreach among providers. These components, especially electronic laboratory reporting, information management, and pooled testing, are most applicable and necessary for scaling up in high-morbidity jurisdictions with well-developed surveillance systems. Surveillance jurisdictions with lower volumes of laboratory reports received may be able to replicate systems to detect test result patterns consistent with AHI using less sophisticated systems. Any jurisdiction interested in scaling up would benefit from strengthening relationships between surveillance staff and providers at STD and HIV clinics.

Given the absence of a national AHI case definition at the time we initiated our AHI surveillance, we established a local definition to guide our efforts. Our case definition was flexible to allow for diverse testing history so that cases could include those with laboratory results ordered on different days. The NYC definition permitted a one-month window of time between the negative/indeterminate test of HIV Ab and detectable VL. CDC's revised 2008 HIV surveillance case definitions document describes a diagnosis of AHI and recommends a same-day test.24 Other published descriptions of AHI cases have also used a more stringent definition of AHI than we employed. For example, Pilcher et al.34 used a pooled testing algorithm for follow-up testing of specimens that were HIV Ab-negative but had detectable viral ribonucleic acid. Only a portion of the acute cases in NYC—those that were detected in DOHMH STD clinics and other select facilities (n=46)—were tested this way. However, we believe that our case definition is well-suited to the diverse patient population and broad range of conditions for HIV testing in NYC. Furthermore, the definition provides additional information on the duration of infection at the time of diagnosis. In the future, we hope to incorporate refinements to distinguish early infection (approximately 6–24 months after HIV acquisition) from AHI. A national case definition for AHI would foster greater recognition among providers and unify local definitions. To this end, CDC established a working group to develop a national AHI case definition for surveillance.

The forthcoming AHI case definition should facilitate physician diagnoses of AHI. However, reporting mandates that do not include negative and indeterminate testing may lead to undercounting of AHI cases. Among the 7,673 new adult and adolescent diagnoses of HIV in 2008–2009, approximately 37% had a quantitative VL test available in the same calendar month as the HIV diagnosis date. We acknowledge that surveillance of AHI would be more complete if all laboratory tests, including negative and indeterminate HIV screening test results, were routinely reported to NYC DOHMH. However, the sheer volume of test data received would be burdensome for processing on a daily basis. The currently reportable laboratory events capture at least some AHI cases through VL test result reporting without being overly burdensome. Nevertheless, our expanded surveillance was facilitated by the providers who diagnosed AHI, enhanced testing detection methods, and increased HIV testing. We were able to detect cases because of provider documentation of AHI in the chart or a sequence of HIV-related tests that enabled the identification of AHI, despite the lack of mandates to report negative and indeterminate HIV tests.

However, AHI surveillance is limited by the quality and accuracy of detection methods. While nearly one-quarter (23.8%) of our cases in 2008–2009 were detected via pNAAT screening, this testing approach is typically available only in settings with a high prevalence of HIV testing. The recent FDA approval of the combination Ag-Ab assay will likely increase the number of AHI cases that we detect by enabling expansion of AHI testing to additional settings. Fostering our citywide AHI surveillance includes DOHMH HIV testing campaigns such as The “Bronx Knows” and the expansion to “Brooklyn Knows,” which seek to test all adolescents and adults in NYC boroughs. NYS has revised its HIV testing law as of July 30, 2010, to allow verbal consent,35 whereas only written consent was previously accepted. The testing initiatives, modified consent law, and AHI screening efforts in the pipeline are expected to enhance the clinical detection of AHI and AHI surveillance moving forward.

We believe that a combination of better-trained staff, more informed providers, and additional DOHMH STD clinics implementing pNAAT may have allowed for increased AHI ascertainment from 2008 to 2009. DOHMH staff conducted outreach to providers about possible AHI cases, and the provider letter and Health Alerts from the DOHMH contributed to better awareness among providers.

While we were able to detect 193 cases of AHI, this number represents <3% of all new diagnoses, suggesting that most HIV diagnoses in NYC occur after the acute stage of infection. With the time frame of acute infection being so short and diagnosis relying on provider recognition and test result patterns, detection is challenging. AHI detection may be increased by frequent testing, and prevention efforts that encourage testing can help improve the yield of AHI surveillance. We have found that HIV prevention and AHI surveillance are multifaceted, linked endeavors. Prevention activities supported by DOHMH promote early diagnosis of HIV and, thus, increase our potential to detect AHI, while our AHI surveillance provides a benchmark for prevention programs through the detection of acute and early infection and facilitates future program planning. Simply having this baseline count of cases that are detected earlier informs prevention activities and will support a test-and-treat prevention strategy.

AHI cases are different than other new HIV diagnoses; we hypothesize that AHI cases are more aware of their risk and have greater knowledge of and access to HIV testing. Risk awareness may be one explanation for the high proportion (77.2%) of those with reported MSM or MSM and IDU transmission risk. To the extent that clear differences between people being diagnosed with AHI and other newly diagnosed HIV cases can be described, people who are likely to be in the former group would be an ideal group to whom preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) should be targeted, as whoever receives PrEP should be at high risk for infection, yet willing to adhere to and also likely to follow up with additional testing after exposure.36,37

CONCLUSIONS

Detecting individuals in the acute stage of HIV infection should be a priority for health departments, given the timely opportunity to prioritize partner notification services and linkage to care for these individuals. At a national level, amending reporting laws to include the full range of HIV-related test results in all jurisdictions and adding AHI to the national HIV surveillance case definition of the stages of HIV illness among adults and adolescents are needed to set the stage for AHI surveillance at the local level. In NYC, existing reporting laws, staffing infrastructure, and other prevention activities supported an expansion of routine surveillance. We prioritized our partner services resources to notify sex- and needle-sharing partners of acute cases of potential exposure and provide HIV testing. Also, if necessary, we provide care linkage to help schedule appointments and provide transportation for acutely infected cases through the support of our existing field services program31,38 and disease intervention specialists of BSTDC.

We are continuing AHI surveillance, building the program, and reporting on AHI case detection in our routine HIV surveillance reports. We have begun expanding our surveillance to assess more specific risk behaviors around the time of infection among those who are acutely infected. In addition, the agency is preparing to evaluate new testing technologies to improve AHI detection. The availability of empirical data on AHI can improve our understanding of the distribution and extent of the HIV epidemic in NYC, suggest avenues for outreach to the clinical community, and help target prevention resources and programming.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth Begier, Arpi Terzian, Alexis Kowalski, Dianiese Figueroa, Wanda Davis, Selam Seyoum, Julie Yuan, Sonny Ly, Roy Shum, Vicki Peters, Chi-Chi Udeagu, Lucia Torian, Monica Sweeney, and Kent Sepkowitz for their expertise and support; and NYC DOHMH public health advisors for performing chart reviews that were critical to the ascertainment of acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection cases.

Footnotes

A portion of cases ascertained as acutely infected were found via pooled HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of HIV antibody-negative individuals. The PCR testing protocol and study were approved by the New York State Department of Health Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program.

This research was supported in part by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cooperative agreement #U62/CCU223460-05-4. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kahn JO, Walker BD. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:33–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerndt PR, Dubrow R, Aynalem G, Mayer KH, Beckwith C, Remien RH, et al. Strategies used in the detection of acute/early HIV infections. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: I. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1037–45. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9580-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zetola NM, Pilcher CD. Diagnosis and management of acute HIV infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:19–48. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.008. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollingsworth TD, Anderson RM, Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:687–93. doi: 10.1086/590501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1873–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20:1447–50. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Jr, Vernazza PL, Leu SY, Stewart PW, et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1785–92. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward WT, Remien RH, Higgins JA, Dubrow R, Pinkerton SD, Sikkema KJ, et al. Behavior change following diagnosis with acute/early HIV infection—a move to serosorting with other HIV-infected individuals. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: III. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1054–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9582-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahrens K, Kent CK, Kohn RP, Nieri G, Reynolds A, Philip S, et al. HIV partner notification outcomes for HIV-infected patients by duration of infection, San Francisco, 2004 to 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:479–84. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181594c61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore ZS, McCoy S, Kuruc J, Hilton M, Leone P. Number of named partners and number of partners newly diagnosed with HIV infection identified by persons with acute versus established HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:509–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ac12bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Morris BL, Scott CA, Rhode ER, et al. Test and treat DC: forecasting the impact of a comprehensive HIV strategy in Washington, DC. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:392–400. doi: 10.1086/655130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Sadr WM, Mayer KH, Hodder SL. AIDS in America—forgotten but not gone. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:967–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherlock M, Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Routine detection of acute HIV infection through RNA pooling: survey of current practice in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:314–6. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000263262.00273.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westreich DJ, Hudgens MG, Fiscus SA, Pilcher CD. Optimizing screening for acute human immunodeficiency virus infection with pooled nucleic acid amplification tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1785–92. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00787-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilcher CD, Wohl DA, Hicks CB. Diagnosing primary HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:488–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-6-200203190-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stekler J, Swenson PD, Wood RW, Handsfield HH, Golden MR. Targeted screening for primary HIV infection through pooled HIV-RNA testing in men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2005;19:1323–5. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180105.73264.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel P, Klausner JD, Bacon OM, Liska S, Taylor M, Gonzalez A, et al. Detection of acute HIV infections in high-risk patients in California. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:75–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218363.21088.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Truong HM, Grant RM, McFarland W, Kellogg T, Kent C, Louie B, et al. Routine surveillance for the detection of acute and recent HIV infections and transmission of antiretroviral resistance. AIDS. 2006;20:2193–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000252059.85236.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acute HIV infection—New York City, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(46):1296–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson AB, Patel P, Sansom SL, Farnham PG, Sullivan TJ, Bennett B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pooled nucleic acid amplification testing for acute HIV infection after third-generation HIV antibody screening and rapid testing in the United States: a comparison of three public health settings. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel P, Mackellar D, Simmons P, Uniyal A, Gallagher K, Bennett B, et al. Detecting acute human immunodeficiency virus infection using 3 different screening immunoassays and nucleic acid amplification testing for human immunodeficiency virus RNA, 2006-2008. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:66–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider E, Whitmore S, Glynn KM, Dominguez K, Mitsch A, McKenna MT. Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-10):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, Garrett PE, Schumacher RT, Peddada L, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2003;17:1871–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. New York Public Health, Title 3, §§2130-2139 (1983)

- 27. New York Public Health, Art. 27-F, §§2780-2787.

- 28. 10 NYCRR §63.4 (2010)

- 29.Blank S, Sweeney M. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2009. Feb 1, Health advisory #4: detection of acute HIV infections in patients seeking routine HIV screening. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepard C. Letter to New York City providers. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2009. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 31.Udeagu CN, Shah D, Shepard CW, Bocour A, Gutierrez R, Begier EM. Impact of a New York City Health Department initiative to expand HIV partner services outside STD clinics. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:107–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.1.3 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New York City HIV/AIDS annual surveillance statistics: definition of HIV Epidemiology and Field Services Program heterosexual transmission category. [cited 2011 Oct 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/ah/hivtables.shtml#abbrev.

- 34.Pilcher CD, McPherson JT, Leone PA, Smurzynski M, Owen-O'Dowd J, Peace-Brewer AL, et al. Real-time, universal screening for acute HIV infection in a routine HIV counseling and testing population. JAMA. 2002;288:216–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. State of New York, Ch. 308, amends §§2130, 2135, 2780-2782, and 2786; adds §2781-a (2010)

- 36.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cates W., Jr After CAPRISA 004: time to re-evaluate the HIV lexicon. Lancet. 2010;376:495–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udeagu CC, Bocour A, Gale I, Begier EM. Provider and client acceptance of a health department enhanced approach to improve HIV partner notification in New York City. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:266–71. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d013e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]