Abstract

The development of 4D CT imaging technology made possible the creation of patient models that are reflective of respiration-induced anatomical changes by adding a temporal dimension to the conventional 3D, spatial-only, patient description. This had opened a new venue for treatment planning and radiation delivery, aimed at creating a comprehensive 4D radiation therapy process for moving targets. Unlike other breathing motion compensation strategies (e.g. breath-hold and gating techniques), 4D radiotherapy assumes treatment delivery over the entire respiratory cycle – an added bonus for both patient comfort and treatment time efficiency. The time-dependent positional and volumetric information holds the promise for optimal, highly conformal, radiotherapy for targets experiencing movements caused by respiration, with potentially elevated dose prescriptions and therefore higher cure rates, while avoiding the uninvolved nearby structures. In this paper, the current state of the 4D treatment planning is reviewed, from theory to the established practical routine. While the fundamental principles of 4D radiotherapy are well defined, the development of a complete, robust and clinically feasible process still remains a challenge, imposed by limitations in the available treatment planning and radiation delivery systems.

Keywords: 4D, radiation therapy, imaging, treatment planning, respiration management

Introduction

Mirroring the need for 4D imaging, 4D radiation treatment planning (4D RTP) stemmed from the desire to better characterize doses to be received by patient anatomies that change over time. Anatomical changes can occur on different time scales (seconds, hours, days, months), can have different causes (e.g. peristaltic, cardiac, respiration, shrinkage or growth), and can be rather random (peristaltic) or more predictable (cardiac, respiratory). While strictly speaking, the terminology “4D” is inclusive of all scenarios enunciated above, currently, in radiation therapy the term is widely and almost exclusively employed to describe anatomical changes induced by respiratory motion. Therefore, for all practical purposes, 4D treatment planning describes the treatment planning process for tumors located in anatomical regions that undergo displacements and deformations (often simply termed “movements”) induced by breathing, such as thorax and abdomen.

4D treatment planning is an extension of the conventional 3D treatment planning (3D RTP). Just like with 3D, 4D treatment planning uses computed tomography data for dose computations; despite the variety of 4D imaging modalities, computed tomography remains the only modality that provides the electron density information necessary for dosimetric calculations. However, unlike the conventional 3D planning, 4D planning uses more than one volumetric image dataset to gather the information required for the evaluation of doses to moving targets and organs at risk. The number of image datasets available after the 4D image acquisition is a user choice, but usually 8–10 sets are generated to sample the entire breathing cycle. These image sets, which depict the anatomy at certain points in time, or states, over a respiratory cycle (of course, within the limits of the achievable accuracy of the entire imaging process), are often complemented with synthetic datasets, such as maximum intensity projection (MIP), minimum intensity projection (MinIP), average intensity projection (AIP) or mid-ventilation (midV). The actual MIP, MinIP and AIP images are generated by projecting the volume of interest into a viewing plane and displaying the maximum CT numbers (for MIP), the minimum CT numbers (for MinIP) or the average CT number (for AIP) that are encountered along the direction of the projection [1]. MidV is a dataset that represents the mobile structures in close to their time-weighted mean-position. Some of the uses of these synthetic datasets have already been described in a previous paper; some others will emerge in the following paragraphs.

The overall goal of 4D RTP is no different than for 3D RTP – maximize the therapeutic ratio by delivering high doses to the tumor, while minimizing doses to normal tissues and organs at risk [2]. The chief prerequisite for achieving this goal is the accurate definition of tumors and normal tissues; dose conformality is a close second, and a direct consequence of the first prerequisite. Adding a temporal dimension to the conventional RTP follows the demand for more accurate target definition in the presence of respiratory motion; a patient model, based on a collection of samples extracted from the time-varying anatomy, provides a dynamic representation of the actual patient.

Looking from a different angle, the inclusion of the temporal dimension also allows for patient specific treatment design, based on treatment planning volumes tailored to the individual patient’s anatomical/physiological characteristics; at least as a matter of principle, the “patient specific” paradigm should lead to treatment plans of better quality for any given patient. Noteworthy here is the fact that the “patient-specific” characterization of the treatment target volume is often perceived as “smaller” than the one generated using the traditional “population”-based margin employed in conjunction with conventional 3D CT, simply because the use of 4D removes, at least in part, uncertainties in target definition that would be otherwise acknowledged by using larger expansions. But this is not necessarily so. Population based margins place at a disadvantage cases having a tumor motion amplitude larger than the population average motion, as parts of the target are almost certain to miss the prescribed treatment dose. For such cases, the patient-specific target volume for which the dosimetric coverage goal (e.g. percentage of the target volume receiving certain percentage of the prescription dose) is set, will be larger than the population-based one, more so if the goal is very ambitious.

4D dose computations

1.1. Principle

In its most general implementation, 4D dose calculation methodology requires as primary input several volumetric image datasets that sample the anatomy over the time-scale of the anatomical changes that are to be accounted for directly in the dosimetric calculation (here, breathing-induced changes). Each dataset is used for planning similarly to the classical 3D approach: structures of interest are contoured, treatment objectives are outlined, and the appropriate beams are set in place to help achieve these objectives. Planning on every available datasets is intended to provide an optimal plan for each sampled anatomy. The next step in the process is to combine these individual doses to generate the composite dose that will be delivered to the “dynamic” patient, modelled based on the sampled datasets. If the composite plan does not meet the planning criteria to a satisfactory level, just like in 3D planning, several iterations of this process may be required [3]. Of all datasets, one will play a master role: the composite dose will be reported on this dataset, which will also be used to evaluate the treatment metrics of interest. This dataset is often referred to as the “planning dataset”, although this is a misnomer, as demonstrated by the discussion above. “Reference dataset” is another adopted terminology, which is perhaps more appropriate. Which dataset from the collection of available samples is to be assigned the “master” role is the planner’s choice. However, one has to keep in mind that the current Record and Verify Systems will use this image set as reference for patient alignment at the time of treatment. It is therefore desirable to choose as “master” a dataset that provides more resemblance with the images provided by the imaging system used in the treatment room. For example, if CBCT is the imaging modality used to aid with patient localization, the dataset that corresponds to the time-average location over the breathing cycle is probably a reasonable choice for the reference dataset [1, 3–4].

The process by which the composite dose is generated using as input individual doses computed on each available dataset is referred to as 4D dose accumulation, dose mapping, or dose reconstruction. It relies upon mapping the anatomical voxels from the reference dataset onto their homologous units from each of the other available datasets (referred to as “secondary” datasets in this paper). The “mapping” (or “tracking”) function is determined through the process of deformable image registration [6], which provides the non-rigid body voxel congruity between the different CT scans. Image registration algorithms used to generate deformation vector maps include those based on thin-plate spline [7], B-spline [8], optical flow [9], viscous fluid [10], finite-element analysis [11] or hybrid approaches [12]. The anatomical voxels are tracked between the reference dataset and the secondary datasets, and the doses received by each of these voxels are accumulated and scored back onto the reference dataset. The accumulation of dose is not a simple arithmetical sum of the individual doses; instead, weighting factors, proportional to the amount of time spent at each breathing stage for which a dataset was sampled, are used to quantify the relative contribution of the dose from each dataset.

1.2. Methods for 4D dose calculation implementation

1.2.1. Dose interpolation methods

The anatomical voxels to be tracked are usually defined on the reference dataset; how they are defined is an arbitrary choice. For convenience, however, they are usually defined as the dose grid voxels from the reference dataset [2, 13–16]. To further ease the process, each dose grid voxel is represented by its center; it is the center that is mapped onto the secondary dataset in accordance with the transformation provided by the image registration. The dose at the tracked location can then be estimated through the direct linear interpolation of the doses at the closest neighboring dose grid center in the secondary dataset (this is necessary because a tracked location does not necessarily land at a voxel center in the homologous dataset) (Fig. 1). If large deformations of the voxels from the reference dataset occur, a refined interpolation approach can be pursued [15]: each voxel from the reference dataset is first subdivided into octants, the center of each octant is mapped to locations on the secondary dataset dose grid, doses at tracked locations are estimated by tri-linear interpolation, and their average value is scored back at the original dose grid center on the reference dataset (Fig. 2). It should be pointed out that, for clinically relevant grid sizes, the use of the refined interpolation is not necessarily equivalent to the use of the direct method at a finer grid resolution because the larger dose calculation grid inherits erroneous voxel dose estimation in the first place. Using a larger dose grid size will likely have minimal impact on the doses reported for tumors or large parallel organs, such as lungs, but may have an adverse effect on serial organs, which are more sensitive to local changes in dose, unlike the parallel organs where the mean dose has been shown to correlate with toxicity [15]. As a rule of thumb, a dose grid size of 3–4 mm appears adequate to minimize the effect of interpolation errors in the cumulative dose.

Figure 1.

Simple interpolation method. w: weights for each breathing phase, D: point dose.

Figure 2.

Refined (“octant”) interpolation method. w: weights for each breathing phase, D and d: point dose.

The direct and the refined dose interpolation methods outlined here are purely geometrical, in the sense that they ignore the changes in voxel density that occur in the deformed voxels, as required by the mass conservation law.

1.2.2. Direct voxel tracking method

Heath and Seuntjens [17] have used a Monte Carlo dose calculation platform to introduce a direct voxel tracking method, which made possible the calculation of energy deposited in a conserved amount of tissue. In short, voxels from the reference dataset are deformed to the secondary dataset, and the densities of the deformed voxels are altered to preserve the voxel mass (Fig. 3). These modified densities are used as input for the particle transport routines used by the Monte Carlo-based dose calculation algorithm. The deformed voxels may have non-planar surfaces, therefore they are approximated by using two planar surfaces, each defined by three nodes; the physically deformed voxels are thus approximated by voxels of dodecahedral shape.

Figure 3.

Direct voxel tracking method. w: weights for each breathing phase, D: point dose, V: volume element.

Differences between the direct voxel tracking method and the interpolation method exist mainly in regions of high dose gradients and in cases where organs move in and out of the field perpendicular to the direction of beam incidence [17]. Such differences are more pronounced when doses from individual datasets are compared, but tend to diminish when summed over the entire breathing cycle. The discrepancies are reduced with decreasing voxel size and motion amplitude. Differences close to 30% in point doses have been demonstrated for the most unfavorable scenarios; however, they extend over small regions and the clinical significance of these changes is debatable.

1.2.3. Energy transfer method

The direct voxel tracking method presented above has been described by Siebers and Zhong [18] as a voxel warping method because it maps the dose at an irregularly shaped voxel in the warped secondary image dataset (the terminology “source image” was used instead in the cited paper) to a regularly shaped voxel in the reference image. Consequently, the irregular boundaries of the dodecahedral voxels must be detected for each particle transport step in the Monte Carlo simulation. It has been estimated that such calculations take 2–6 times longer than a standard DOSXYZnrc dose computation [19] due to the number of irregular boundaries that must be checked at each particle transport step. In addition, to prevent collapsing or merging of the dodecahedral voxels on the source image due to image registration errors, the voxel size must be much larger than the image registration errors.

Siebers and Zhang [18] have proposed a more efficient and more natural approach to the problem. Their solution, called the energy transfer method, simulates the particle transport within the secondary image dataset, but scores the energy deposition at its warped location in the reference image (Fig. 4). Therefore, no irregular boundary detection is required, and the dodecahedral approximation is unnecessary.

Figure 4.

Energy transfer method. w: weights for each breathing phase, D: point dose, E: radiant energy absorbed, m: mass.

This method separates the particle transport and particle scoring geometries: particle transport takes place in the typical rectilinear coordinate system of the source image, while energy deposition scoring takes place in a desired reference image via use of deformable image registration. Dose is therefore the energy deposited per unit mass in the reference image.

The separate treatment of particle transport and energy deposition within the dose mapping process eliminates the inaccuracy inherent to the interpolation-based methods. The energy deposited in each voxel is treated as a pseudo continuous distribution instead of the dose accumulated at the voxel center of mass as in the center of mass or subdivisions thereof, such as octants for the trilinear method. The infinitesimal particle-based energy deposition mapping provides a natural and accurate way to map dose. This approach also avoids the voxel merging related issues suffered by the voxel warping method and allows accurate high-resolution deformable dose mapping.

The energy transfer method introduced by Siebers and Zhang is a prerogative of the Monte Carlo dose computation engines which is volumetric, in the sense that it allows for the energy deposition to be integrated over the volume of the voxels, unlike the non-Monte Carlo algorithms which are point-based computations, with the point separation indicated by the voxel coordinates and spacing.

Generating cumulative dose distributions for deforming anatomies using Monte Carlo calculation algorithms is undoubtedly more rigorous and more elegant than the interpolation method. Unfortunately, the practical applicability of such approaches is still limited by the unavailability of Monte Carlo dose computation algorithms on a large scale and by the large amount time usually required by such calculations, which renders them infeasible for routine clinical use. Last, but not least, the clinical relevance of the differences between the more accurate Monte Carlo based methods and the simplified interpolation based methods is yet to be demonstrated.

1.3. 4D radiation delivery for 4D treatment planning

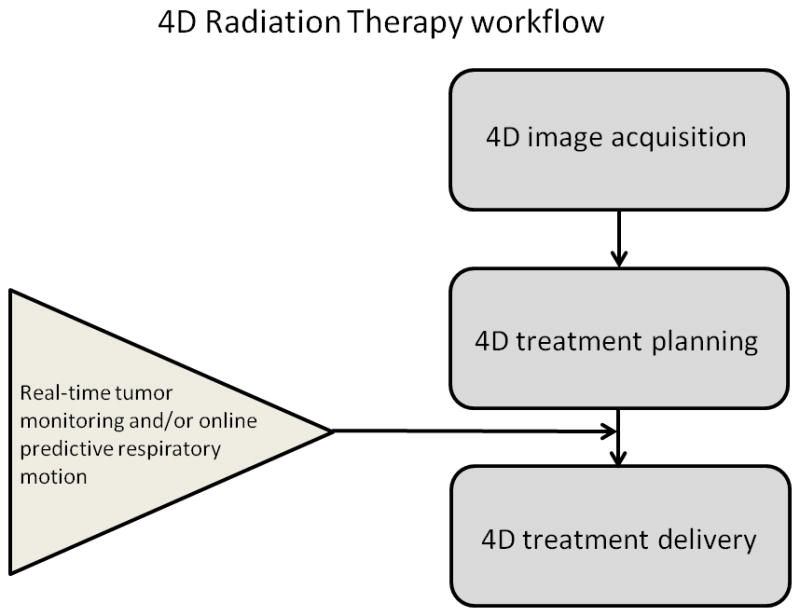

As already mentioned earlier, each image dataset reconstructed from a 4D scan can be used to generate the best achievable treatment plan for that respective breathing phase. However, the effort remains nothing more than an exercise unless it is complemented by a delivery of that plan to the phase for which it was designed. Such a delivery method would involve the real time tracking of the tumor such that a certain tumor location can be synchronized with the plan intended for that breathing phase. The ideal workflow of a true, complete, 4D radiation treatment is depicted in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Workflow diagram of a 4D radiation treatment.

Several conditions must be fulfilled for the successful realization of the real-time tumor tracking in radiation treatment delivery.

First, the real-time movements of the structures of interest have to be either monitored accurately or a reliable motion predictive model has to be in place.

Implanted radiopaque markers have emerged as a fairly reliable means (provided that implantation is feasible) of tracking the motion of lung cancer during radiotherapy [20, 21] and their real-time detection using fluoroscopy has been achieved with around 2 mm accuracy [22–25]. The uses of MV or kV portal imagers, or CBCT, are alternatives to fluoroscopic imaging [26–29]. The input information for target position determination can also be acquired using external optical systems [30] or electromagnetic transponders [31]. The Synchrony Respiratory Tracking System from Cyberknife (Accuray, Inc., Sunnyvale, California, U.S.A.) uses a combination of some of the methods identified above. The patient wears a vest-like garmet that has light-emitting diodes attached to it, tracked by charged-coupled device (CCD) cameras mounted on the ceiling. Several gold fiducial marker implanted in the tumor are periodically imaged by two orthogonal diagnostic X-ray sources and their location is correlated with the LEDs movements.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of the newest technologies sought for guidance in localizing tumors in real-time, and it holds the promise of superior soft tissue visualisation. MRI has been used to investigate organ movements in thorax, abdomen and pelvis [32–37]. Hybrid MRI-linac prototype systems are now available in Netherlands, Canada and United States [38–42].

Emerging technologies include the use of gamma rays from positron emitters in tumors [43–45]. Predicting the internal motion induced by breathing is not an easy task, since frequency changes, amplitude variations, baseline shifts, occur on a regular basis both inter- and intra-fraction. Predictive models based on linear filtering, Kalman filtering, neural networks, local regression, autoregressive-moving average model have been developed, but they are not yet reliable enough clinically [46–50].

Second, the radiation delivery equipment must have the ability to follow closely the organ positional changes, which is especially challenging when deviations occur from the motion model assumed at the time of planning. The methods proposed for tumor tracking for radiation delivery using linear accelerators include dynamic multileaf collimator tracking [51–59] and couch position corrections [60].

The major issues identified and still awaiting adequate consideration and mitigation before the real-time based technology can be deemed clinically effective are latencies in the treatment system related image acquisition and processing, communication delays, and control system processing, to name a few. Reducing the sampling rate imposed for tracking could help, but as matter of principle, this solution would work against the very reason that creates the basis for pursuing real-time anatomy tracking.

1.4. Simplified approaches for 4D treatment planning

4D radiation delivery based on 4D treatment planning constitutes the gold standard of 4D radiation therapy, but the implementation of the complete process is not yet possible for reasons highlighted in the previous sections. Not mentioned so far, but certainly important, is the fact that with 4D RT we are facing a new class of uncertainties associated with the new imaging, planning and delivery methods and procedures, which are yet to be properly quantified in order to establish whether or not their cumulative effect compares favorably with the overall uncertainty of the conventional 3D radiation therapy process. Moreover, even if all current holdbacks are reduced to insignificant levels or even eliminated, the overall process still remains clinically prohibitive due to the enormous requirement for personnel, as well as computational and time resources necessary to sustain such an involved procedure. Finally yet importantly, as already stated on several occasions, the clinical benefit of full 4D RT is still unknown and perhaps questionable.

All things considered, simplified approaches, which could be implemented with reduced resources, while still maintaining a patient-specific oriented planning and treatment strategy, have been justifiably sought. Of all aspects outlined in the discussion so far, of utmost importance for a time-variable anatomy are the proper target definition (i.e. inclusive of all spatial distribution of the tumor over the breathing cycle), and its subsequent irradiation, whereas the first aspect to compromise on is the dynamic delivery of radiation to a real-time tracked target. This will conveniently allow for a simplified planning process as well. The altered, simplified process resembles very much the conventional 3D planning workflow and can be summarized as follows: on a reference dataset of choice, a target is defined that encompasses all tumor locations and a plan is designed to cover this region with the prescribed dose; the plan will be delivered with the patient breathing freely, after being properly setup such that the tumor is located inside the target region used for planning. The target that meets the requirement of being the envelope of all tumor locations is the previously defined ITV, which can be contoured on a MIP dataset for pulmonary tumors (or MinIP for hepatical tumors), thus eliminating the tedious and time-consuming process of contouring on each image dataset from the 4D collection. The next question that needs to be addressed is what dataset should be chosen for planning. The choice has to meet two demands: first, the computation of dose on this dataset should approximate as closely as possible the cumulative 4D dose that would otherwise be computed using all available datasets; second, the anatomy represented by this image set (tumor location in particular) should be correlated with the tumor image that will be acquired by the imaging system that will be used for localization prior to radiation delivery.

On the first account, Rosu et al. [61] have compared 4D cumulative doses computed using 11 datasets with 4D doses using fewer datasets – 6, or 2 (Exhale and Inhale) and found them to be in good agreement. Moreover, the metrics associated with the full 4D dose calculation were reproduced within about 2% (differences of this magnitude will likely be clinically inconsequential) not only by the calculations based on fewer datasets, but even by a single calculation performed on the dataset that corresponds to the time-average location of the moving tumor of each individual patient. The study by Rosu et al. used a “brute-force” approach on a number of patients for demonstrating that using the dataset that corresponds to the time-average location is a reasonable substitute for the calculation of the treatment metrics of interest. Wolthaus et al. [1] have reached a similar conclusion by pursuing a more analytical analysis. Their choice for the single dataset is the mid-ventilation scan discussed above and was based on prior studies by Engelsman et al. [62] and Witte et al. [63] that showed that if a tumor is irradiated at the average position, dose coverage can be achieved even when the tumor is not entirely within the high-dose region for a (small) part of the breathing cycle due to the presence of wider beam penumbra inside the lung. The application of the mid-ventilation concept led to an average reduction in the irradiated volume of about 20% for tumors with a diameter of 40 mm.

The disadvantage of using the time-average location is that tumors usually move at greatest speed when passing through this location, which may result in more image artifacts. However, a study by Rietzel et al. [14] suggests that such artifacts are smaller than those originating from irregular breathing.

The Netherlands group [66] pointed out that the single dataset approach to planning method accounts for respiration-induced geometric variation (the tumor volume receives doses in different positions), but does not account for the fact that the tissue density at a specific location changes over the respiratory cycle, unlike the full 4D treatment planning that accounts for both geometry and density variations. The concern was addressed in a study by Mexner et al. [64]. In one scenario, a plan was created on the mid-ventilation dataset and dose was computed. Subsequently, this dose was copied on all the other datasets and accumulated. This scenario ignored the effect of the density variations on dose. In another scenario, the plan from the mid-ventilation image dataset was first copied on each available dataset, doses were recalculated, and then accumulated. This calculation provided a full account for both geometrical and density variations. The study found that the overall effect of the density variations was small, even in the presence of large movements, and concluded that a full 4D dose calculation – the only way of accounting for density variations from each image dataset – was not required. Notable, the dose to target from the mid-ventilation plan, was slightly higher than the one predicted by the complete 4D cumulative dose calculation. This effect has been noted by others as well [65] that have shown that the high-dose region “follows” the tumor and moves synchronously with the breathing motion; due to its higher density, the cancerous tissue absorbs more dose than the surrounding low density lung tissue.

Glide-Hurst et al. [66] and, separately, Admiraal et al. [67] explored a related method to account for the tissue density changes using a single dose calculation. Rather than use the mid-ventilation image, the average-intensity dataset was created from the individual 4D breathing state images. Dose was calculated on this average image and cumulative dose estimated using a similar method as Mexner et al., where the dose was copied to all image sets and accumulated using image registration. Similar to Mexner et al., the dose using the average image method and full 4D method was found similar in a small patient sample.

Altogether, the studies referenced here suggest that using some “average” anatomy/location for planning could ensure sufficiently accurate dose evaluation with the least amount of user intervention. The overall process, as outlined in this last section is truly 4D at imaging only. However, as it is less technologically complex than real-time tracking, it is more realistic at this time and a simplified delivery process still benefits from 4D imaging data because it better predicts doses to be received by a deforming anatomy. For perfectly periodic respiration, average methods may achieve similar performance as real-time tracking [68]. For drifting or changing respiratory patterns, tracking may be the more accurate option, although this remains to be evaluated.

Intensity modulated therapy treatment (IMRT) planning raised additional concerns regarding the interplay effects between organ motion and multileaf collimator motion unique to the dynamic IMRT delivery. Several studies investigated this aspect [69–72] and it was concluded that the interplay effect was not significant dosimetrically for protracted treatment regimens. Seco et al. [73] investigated the interplay effect for IMRT segments with a small number of monitor units and concluded that for most clinical cases the effect are usually small when multiple beams are used.

Conclusions

The foundation for 4D treatment planning is established, but the methodology is not yet available for routine use in commercial planning systems. Consequently, the ideal 4D RT is implemented clinically with a degree of complexity that decreases from imaging to treatment planning to treatment delivery: the imaging segment is 4D, the treatment planning is 3+D (that is 3D in the conventional sense, but using as input some 4D imaging information), whereas the delivery of radiation is 3D. However, the simplified forms of 4D treatment planning that have been implemented allow for customized plans designed to deliver the prescribed treatment dose to patient-specific, motion-inclusive targets.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Matthias Söhn for assisting with literature review. This publication was made possible by grant number NIH P01CA116602 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Wolthaus JW, Schneider C, Sonke JJ, van Herk M, Belderbos JS, Rossi MM, et al. Mid-ventilation CT scan construction from four-dimensional respiration-correlated CT scans for radiotherapy planning of lung cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1560–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraass BA. The development of conformal radiation therapy. Med Phys. 1995;22:1911–21. doi: 10.1118/1.597446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keall PJ, Siebers JV, Joshi S, Mohan R. Monte Carlo as a four-dimensional radiotherapy treatment-planning tool to account for respiratory motion. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:3639–48. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/16/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hugo GD, Liang J, Campbell J, Yan D. On-line target position localization in the presence of respiration: a comparison of two methods. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Wu QJ, Marks LB, Larrier N, Yin FF. Cone-beam CT localization of internal target volumes for stereotactic body radiotherapy of lung lesions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1618–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crum WR, Hartkens T, Hill DL. Non-rigid image registration: theory and practice. Br J Radiol. 2004;77(2):S140–53. doi: 10.1259/bjr/25329214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bookstein FL. Principal warps: Thin-plate splines and the decomposition of deformations. Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, IEEE Transactions on. 1989;11:567–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartkens T. PhD Thesis. London: University of London; 2003. Measuring, analyzing, and visualizing brain deformation using non-rigid registration. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrero T, Zhang G, Huang TC, Lin KP. Intrathoracic tumour motion estimation from CT imaging using the 3D optical flow method. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:4147–61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/17/022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen GE, Carlson B, Chao KS, Yin P, Grigsby PW, Nguyen K, et al. Image-based dose planning of intracavitary brachytherapy: registration of serial-imaging studies using deformable anatomic templates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:227–43. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock KK, Hollister SJ, Dawson LA, Balter JM. Technical note: creating a four-dimensional model of the liver using finite element analysis. Med Phys. 2002;29:1403–5. doi: 10.1118/1.1485055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Söhn M, Birkner M, Chi Y, Wang J, Di Y, Berger B, Alber M. Model independent, multimodality deformable image registration by local matching of anatomical features and minimization of elastic energy. Med Phys. 2003;30:290–5. doi: 10.1118/1.2836951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brock KK, McShan DL, Ten Haken RK, Hollister SJ, Dawson LA, Balter JM. Inclusion of organ deformation in dose calculations. Med Phys. 2008;35:866–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rietzel E, Chen GT, Choi NC, Willet CG. Four-dimensional image-based treatment planning: Target volume segmentation and dose calculation in the presence of respiratory motion. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1535–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosu M, Chetty IJ, Balter JM, Kessler ML, McShan DL, Ten Haken RK. Dose reconstruction in deforming lung anatomy: dose grid size effects and clinical implications. Med Phys. 2005;32:2487–95. doi: 10.1118/1.1949749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaly B, Kempe JA, Bauman GS, Battista JJ, Van Dyk J. Tracking the dose distribution in radiation therapy by accounting for variable anatomy. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:791–805. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/5/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath E, Seuntjens J. A direct voxel tracking method for four-dimensional Monte Carlo dose calculations in deforming anatomy. Med Phys. 2006;33:434–45. doi: 10.1118/1.2163252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siebers JV, Zhong H. An energy transfer method for 4D Monte Carlo dose calculation. Med Phys. 2008;35:4096–105. doi: 10.1118/1.2968215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babcock K, Cranmer-Sargison G, Sidhu N. Increasing the speed of DOSXYZnrc Monte Carlo simulations through the introduction of nonvoxelated geometries. Med Phys. 2008;35:633–44. doi: 10.1118/1.2829874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seppenwoolde Y, Shirato H, Kitamura K, Shimizu S, van Herk M, Lebesque JV, et al. Precise and real-time measurement of 3D tumor motion in lung due to breathing and heartbeat, measured during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:822–34. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirato H, Seppenwoolde Y, Kitamura K, Onimura R, Shimizu S. Intrafractional tumor motion: lung and liver. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14:10–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semradonc.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyamoto N, Ishikawa M, Bengua G, Sutherland K, Suzuki R, Kimura S, et al. Optimization of fluoroscopy parameters using pattern matching prediction in the real-time tumor-tracking radiotherapy system. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:4803–13. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/15/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onimaru R, Shirato H, Fujino M, Suzuki K, Yamazaki K, Nishimura M, et al. The effect of tumor location and respiratory function on tumor movement estimated by real-time tracking radiotherapy (RTRT) system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onodera Y, Nishioka N, Yasuda K, Fujima N, Torres M, Kamishima T, et al. Relationship between diseased lung tissues on computed tomography and motion of fiducial marker near lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1408–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirato H, Suzuki K, Sharp GC, Fujita K, Onimaru R, Fujino M, et al. Speed and amplitude of lung tumor motion precisely detected in four-dimensional setup and in real-time tumor-tracking radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamson J, Wu Q. Prostate intrafraction motion evaluation using kV fluoroscopy during treatment delivery: a feasibility and accuracy study. Med Phys. 2008;35:1793–806. doi: 10.1118/1.2899998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho B, Poulsen PR, Sloutsky A, Sawant A, Keall PJ. First demonstration of combined kV/MV image-guided real-time dynamic multileaf-collimator target tracking. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:859–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulsen PR, Cho B, Keall PJ. A method to estimate mean position, motion magnitude, motion correlation, and trajectory of a tumor from cone-beam CT projections for image-guided radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1587–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulsen PR, Cho B, Keall PJ. Real-time prostate trajectory estimation with a single imager in arc radiotherapy: a simulation study. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:4019–35. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/13/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmerman J, Korreman S, Persson G, Cattell H, Svatos M, Sawant A, et al. DMLC motion tracking of moving targets for intensity modulated arc therapy treatment: a feasibility study. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:245–50. doi: 10.1080/02841860802266722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawant A, Smith RL, Venkat RB, Santanam L, Cho B, Poulsen P, et al. Toward submillimeter accuracy in the management of intrafraction motion: the integration of real-time internal position monitoring and multileaf collimator target tracking. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:575–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korin HW, Ehman RL, Riederer SJ, Felmlee JP, Grimm RC. Respiratory kinematics of the upper abdominal organs: a quantitative study. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23:172–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plathow C, Ley S, Fink C, Puderbach M, Hosch W, Schmähl A, Debus J, Kauczor H-U. Analysis of intrathoracic tumor mobility during whole breathing cycle by dynamic MRI. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:952–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doyle VL, Howe FA, Griffiths JR. The effect of respiratory motion on CSI localized MRS+ Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:2093–104. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/8/303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrne TE. A review of prostate motion with considerations for the treatment of prostate cancer. Med Dosim. 2005;30:155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghilezan MJ, Jaffray DA, Siewerdsen JH, van Herk M, Shetty A, Sharpe MB, Jafri SZ, Vicini FA, Matter RC, Brabbins DS, Martinez AA. Prostate gland motion assessed with cine-magnetic resonance imaging (cine-MRI) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:406–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mah D, Freedman G, Milestone B, Hanlon A, Palacio E, Richardson T, Movsas B, Mitra R, Horwitz E, Hanks GE. Measurement of intrafractional prostate motion using magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:568–75. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lagendijk JJW, Raaymakers BW, Raaijmakers AJE, Overweg J, Brown KJ, Kerkhof EM, Van Der Put RW, Hårdemark B, van Vulpen M, van Der Heide UA. MRI/linac integration. Radiother Oncol. 2008;86:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raaymakers BW, Raaijmakers AJE, Kotte ANTJ, Jette D, Lagendijk JJW. Integrating a MRI scanner with a 6 MV radiotherapy accelerator: dose deposition in a transverse magnetic field. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:4109–18. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/17/019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dempsey JF, Benoit D, Fitzsimmons JR, Haghighat A, Li JG, Low DA, Mutic S, Palta JR, Romeijn HE, Sjoden GE. A device for realtime 3D image-guided. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:S202. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fallone BG, Murray B, Rathee S, Stanescu T, Steciw S, Vidakovic S, Blosser E, Tymofichuk D. First MR images obtained during megavoltage photon irradiation from a prototype integrated linac-MR system. Med Phys. 2009;36:2084–8. doi: 10.1118/1.3125662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirkby C, Murray B, Rathee S, Fallone BG. Lung dosimetry in a linac-MRI radiotherapy unit with a longitudinal magnetic field. Med Phys. 2010;37:4722–32. doi: 10.1118/1.3475942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamberland M, Wassenaar R, Spencer B, Xu T. Performance evaluation of real-time motion tracking using positron emission fiducial markers. Med Phys. 2011;38:810–9. doi: 10.1118/1.3537206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grills IS, Yan D, Black QC, Wong CY, Martinez AA, Kestin LL. Clinical implications of defining the gross tumor volume with combination of CT and 18FDG-positron emission tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:709–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu T, Wong JT, Shikhaliev PM, Ducote JL, Al-Ghazi MS, Molloi S. Real-time tumor tracking using implanted positron emission markers: concept and simulation study. Med Phys. 2006;33:2598–609. doi: 10.1118/1.2207213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy MJ, Pokhrel D. Optimization of an adaptive neural network to predict breathing. Med Phys. 2009;36:40–7. doi: 10.1118/1.3026608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren Q, Nishioka S, Shirato H, Berbeco RI. Adaptive prediction of respiratory motion for motion compensation radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:6651–61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/22/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roland T, Mavroidis P, Shi C, Papanikolaou N. Incorporating system latency associated with real-time target tracking radiotherapy in the dose prediction step. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:2651–68. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/9/015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruan D, Fessler JA, Balter JM. Real-time prediction of respiratory motion based on local regression methods. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:7137–52. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/23/024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharp GC, Jiang SB, Shimizu S, Shirato H. Prediction of respiratory tumour motion for real-time image-guided radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:425–40. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/3/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keall PJ, Cattell H, Pokhrel D, Dieterich S, Wong KH, Murphy MJ, et al. Geometric accuracy of a real-time target tracking system with dynamic multileaf collimator tracking system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1579–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keall PJ, Kini VR, Vedam SS, Mohan R. Motion adaptive x-ray therapy: a feasibility study. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46:1–10. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/1/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawant A, Venkat R, Srivastava V, Carlson D, Povzner S, Cattell H, et al. Management of three-dimensional intrafraction motion through real-time DMLC tracking. Med Phys. 2008;35:2050–61. doi: 10.1118/1.2905355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao W, Riaz N, Lee L, Wiersma R, Xing L. A fiducial detection algorithm for real-time image guided IMRT based on simultaneous MV and kV imaging. Med Phys. 2008;35:3554–64. doi: 10.1118/1.2953563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neicu T, Shirato H, Seppenwoolde Y, Jiang SB. Synchronized moving aperture radiation therapy (SMART): average tumour trajectory for lung patients. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:587–98. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/5/303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papiez L, Rangaraj D. DMLC leaf-pair optimal control for mobile, deforming target. Med Phys. 2005;32:275–85. doi: 10.1118/1.1833591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suh Y, Yi B, Ahn S, Kim J, Lee S, Shin S, et al. Aperture maneuver with compelled breath (AMC) for moving tumors: a feasibility study with a moving phantom. Med Phys. 2004;31:760–6. doi: 10.1118/1.1650565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tacke M, Nill S, Oelfke U. Real-time tracking of tumor motions and deformations along the leaf travel direction with the aid of a synchronized dynamic MLC leaf sequencer. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:N505–12. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/22/N01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McQuaid D, Webb S. IMRT delivery to a moving target by dynamic MLC tracking: delivery for targets moving in two dimensions in the beam’s eye view. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:4819–39. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/19/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Souza WD, Naqvi SA, Yu CX. Real-time intra-fraction-motion tracking using the treatment couch: a feasibility study. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:4021–33. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/17/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosu M, Balter JM, Chetty IJ, Kessler ML, McShan DL, Balter P, et al. How extensive of a 4D dataset is needed to estimate cumulative dose distribution plan evaluation metrics in conformal lung therapy? Med Phys. 2007;34:233–45. doi: 10.1118/1.2400624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Engelsman M, Damen EM, De Jaeger K, van Ingen KM, Mijnheer BJ. The effect of breathing and set-up errors on the cumulative dose to a lung tumor. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Witte MG, van der Geer J, Schneider C, Lebesque JV, van Herk M. The effects of target size and tissue density on the minimum margin required for random errors. Med Phys. 2004;31:3068–79. doi: 10.1118/1.1809991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mexner V, Wolthaus JW, van Herk M, Damen EM, Sonke JJ. Effects of respiration-induced density variations on dose distributions in radiotherapy of lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guckenberger M, Wilbert J, Krieger T, Richter A, Baier K, Meyer J, et al. Four-dimensional treatment planning for stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glide-Hurst CK, Hugo GD, Liang J, Yan D. A simplified method of four-dimensional dose accumulation using the mean patient density representation. Med Phys. 2008;35:5269–77. doi: 10.1118/1.3002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Admiraal MA, Schuring D, Hurkmans CW. Dose calculations accounting for breathing motion in stereotactic lung radiotherapy based on 4D-CT and the internal target volume. Radiother Oncol. 2008;86:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang P, Hugo GD, Yan D. Planning study comparison of real-time target tracking and four-dimensional inverse planning for managing patient respiratory motion. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1221–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bortfeld T, Jokivarsi K, Goitein M, Kung J, Jiang SB. Effects of intra-fraction motion on IMRT dose delivery: statistical analysis and simulation. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:2203–20. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/13/302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chui CS, Yorke E, Hong L. The effects of intra-fraction organ motion on the delivery of intensity-modulated field with a multileaf collimator. Med Phys. 2003;30:1736–46. doi: 10.1118/1.1578771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jiang SB, Pope C, Al Jarrah KM, Kung JH, Bortfeld T, Chen GT. An experimental investigation on intra-fractional organ motion effects in lung IMRT treatments. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:1773–84. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/12/307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schaefer M, Munter MW, Thilmann C, Sterzing F, Haering P, Combs SE, Debus J. Influence of intra-fractional breathing movement in step-and-shoot IMRT. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:N175–9. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/12/n03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seco J, Sharp GC, Turcotte J, Gierga D, Bortfeld T, Paganetti H. Effects of organ motion on IMRT treatments with segments of few monitor units. Med Phys. 2007;34:923–34. doi: 10.1118/1.2436972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]