Abstract

The scrotal and perineal area serves a special function. It is the pelvic outlet for the gastrointestinal tract, urinary system, and sexual function. In the male, the scrotum allows testicular mobility to reduce trauma and allow optimal thermal regulation for spermatogenesis. Trauma, infection, and cancer resection create defects that require reconstruction. The reconstructive goal here is to obtain durable coverage, function, and lastly aesthetic outcome. Pedicled local and regional flaps are the mainstay for this area. Due to the special function and appearance of the scrotum, reconstructive options for total scrotal defect always fall far short of the native scrotum. On the other hand, perineal reconstruction is overall satisfactory.

Keywords: Scrotal wound, perineal wound, flap coverage

The scrotal and perineal area serves a special function. It is the confluence of urologic, sexual, and gastrointestinal functions. In the male, the scrotum allows testicular mobility to reduce trauma and allows optimal thermal regulation for spermatogenesis. The scrotum is made up of specialized skin and dartos muscle, which can contract and relax to dissipate heat to allow optimal temperature regulation for sperm production.1,2 Inferiorly, the perineal region houses pelvic muscles and anal sphincter muscles to allow defecation and flatus to pass at the proper time. Pelvic muscles provide dynamic support and prevent pelvic prolapse and hernia. In females, pelvic relaxation often after childbirth presents as stress incontinence from cystocele, vaginal prolapse, and stool soilage from rectocele. In males, pelvic prolapse and hernia cause pelvic painful bulge and often occur after surgical resection without reconstruction. Dynamic muscle functions such as scrotal contraction and anal sphincter restoration after total resection have not been possible. Thus, patients should be informed before oncologic resections that reconstructive efforts will fall short of their expectations. Infertility may occur after total scrotal reconstruction.

RECONSTRUCTIVE APPROACH

Goals

Because dynamic functions of scrotum and anal sphincters cannot be restored after total loss, the reconstructive goal here is to provide wound healing, limited function, and acceptable appearance. A superficial defect can be closed by primary closure, skin grafting, and local flaps. Radical resection may create a through and through perineum and pelvic defect. Reconstructive efforts here should focus on obliterating dead space with vascularized tissue to avoid infection, bowel incarceration, and provide pelvic support to minimize pelvic bulge or hernia. Then external coverage can be done by skin grafting, and local or regional flaps depending on the nature of the defects and available tissues.

Timing and Reconstructive Options

The timing of reconstruction depends on the cause of defect. Traumatic and infectious defects require serial débridements until local tissue exhibit a viable wound bed. Scrotal specialized tissue and anal sphincters should be preserved if possible during débridement. Hence, reconstruction in this patient population is frequently delayed. Fournier gangrene is a life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis of the genitalia and perineum. It occurs more often in men than women even after a minor trauma to this area in immunocompromised hosts such as patients with diabetes mellitus, obesity, HIV, substance abuse, and cancer. Polymicrobial flora cause rapid extensive soft tissue necrosis and sepsis.3,4,5,6,7 Repeated radical débridements, antibiotic treatment, and medical management are necessary. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy if available is helpful.8 Once local tissue shows evidence of healing then reconstruction can proceed. Primary closure affords the best color match and potential function especially in partial scrotal defect. Frequently, extensive superficial defect from trauma or malignancy can be covered by a split thickness skin graft to obtain wound healing (Fig. 1). Then subsequent reconstruction and revision if necessary can be done when the patient is stable. Skin graft impairs scrotal movement and has been reported to cause azoospermia in two of three cases after traumatic scrotal avulsion.9 Likewise, bulky flap elevates testicular temperature and may impair spermatogenesis. Debulking of such thick flap has been reported to improve sperm production by Wang.10,11

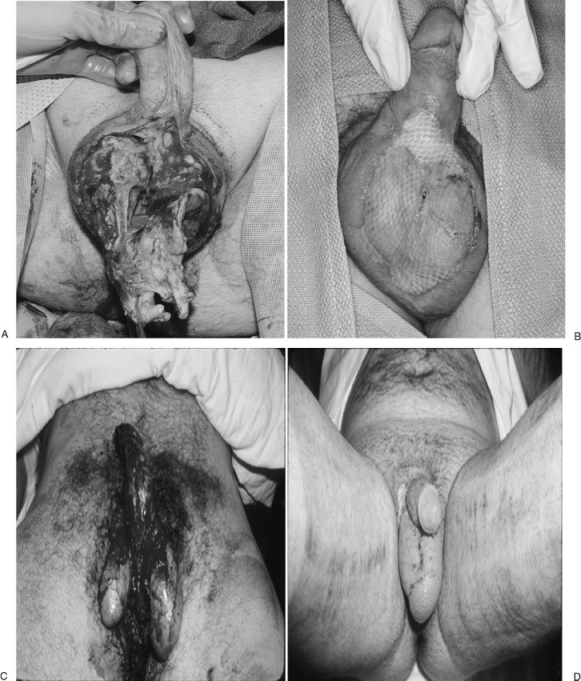

Figure 1.

Scrotal infection (A,B) and trauma (C,D) created significant defects. A healthy wound bed after debridement allowed split thickness skin graft to obtain healing. Note the lack of color match and dynamic function of a normal scrotum. (Courtesy of Dr. P.G. Arnold.)

On the other hand, oncologic defects are reconstructed after margins are free of tumor and preferentially immediately after resection. Existing oncologic operative field provides excellent exposure and easy access to uninflamed tissue for reconstruction options. Immediate wound closure shortens overall morbidity to the patient. Delayed reconstruction requires painful dressing changes and may cause progressive necrosis of irradiated wound. Malignancy represents a more frequent cause of defects that require complex reconstruction in cancer centers. For instance, extramammary Paget disease of the scrotum and perineum, an uncommon neoplasm, presents as pruritic hyper- or hypopigmented, excoriated lesions.12,13,14 It is a rare, slow-growing adenocarcinoma. Internal malignancies from urethral, bladder, prostate, testis, and colon origin must be ruled out. Multiple incisional biopsies and then wide local excision with frozen sections are necessary to confirm free margins before reconstruction. Bowen disease and squamous cell carcinoma of this area are also causes for resections.15,16,17,18 Often, defects from such resections are superficial and limited to skin and subcutaneous tissue. Primary closure if possible provides a good color match and potential scrotal function. Otherwise, a simple skin graft or local fasciocutaneous flap is often adequate to obtain wound healing, but fails to allow thermal regulation for the testes. In the case of advanced penile cancer, extended resection can still leave some residual viable scrotal tissue for wound closure without need of any other approaches (Fig. 2). When primary closure is not possible, local options are based on the terminal branch of the external pudendal vessels, which supply the Singapore flaps for vaginal reconstruction.19,20 Bilateral V-Y perineal flaps from the same vascular territory can provide good coverage option that is more durable and aesthetic than skin grafting (Fig. 3). This flap like all flaps is difficult in obese patients due to difficult donor site closure and potential flap fat necrosis. A local flap in case of irradiation has the disadvantage of using the irradiated tissue, which can increase wound complications and flap loss.21,22 With the advance of perforator flap concept and free-style flap design, local and regional options will be expanded.23,24,25 The thigh vasculature such as medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries, inferior gluteal artery can provide multiple regional options of fasciocutaneous flaps for the perineoscrotal defects. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flap without irradiation injury can provide excellent coverage for this area.26,27,28

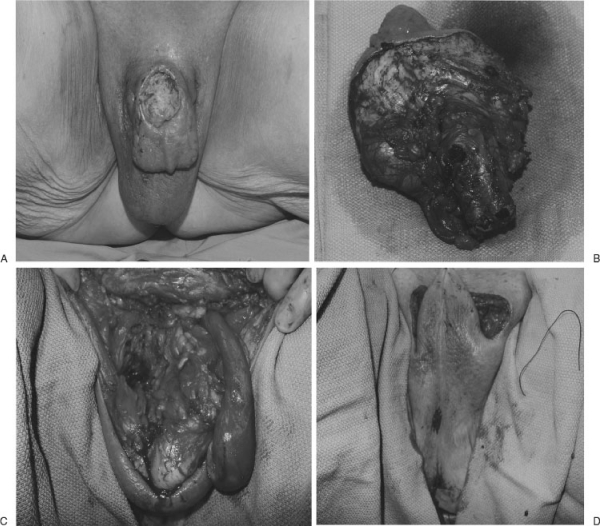

Figure 2.

Primary closure provides the best color match and potential function in partial scrotal defect. This patient with a locally advanced penile cancer underwent total penectomy and partial scrotal resection. Remaining scrotal tissue was used to cover the defect.

Figure 3.

Local flaps provides good color match. After a free margin was obtained for this perineal recurrent squamous cell carcinoma, the terminal branches of the internal pudendal vessels were still present per a handheld Doppler exam. The bilateral V-Y perineal flaps could provide tissue with excellent color match. Prior irradiation of local tissue, a disadvantage in local option, caused a midline wound dehiscence (middle panel), which subsequently healed by secondary intention (bottom panel).

Among all defects, radical resection of recurrent tumor after irradiation creates significant problems that require careful planning during resection and reconstruction. Preoperative planning must be communicated with the ablative team to optimize reconstruction and outcome. Local tissue without tumor should be saved as a potential source for closure. Vascular supply to the potential flaps must not be disrupted unless there is tumor invasion. Irradiated tissue without tumor invasion should not be resected by the ablative team. Ostomies should not be brought through the rectus muscle until the plastic surgery team has inspected the defect and selected the reconstructive option. For instance, radical anterior and posterior exenteration for local/pelvic recurrence after prostatic or colorectal would create perineal full thickness soft tissue and pelvic floor defect as potential hernia and dead space for bowel obstruction and abscess. Bowel and urine conduit diversion ostomies are necessary. With existing laparotomy, a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (VRAM) with skin from the supraumbilical area provides excellent soft tissue bulk to obliterate dead space to prevent abscess and hernia.29,30,31,32 At the same time, the flap skin island creates a durable coverage to the perineal defect. We prefer the vertical rather than the transverse skin island design because epigastric skin comfortably reaches the perineum without tension. Donor site fascial closure does not require a mesh because the intact anterior rectus sheath below the arcuate line can be simply reapproximated to the posterior sheath just above the arcuate line. Finally, abdominal skin closure in vertical skin design occurs along the midline without wide undermining and sitting the patient up as in the TRAM. The stool and urinary diversion ostomies both can be brought out through one rectus muscle only after the plastic surgery team elevates the VRAM (Fig. 4). In some cases, bilateral rectus blood supplies are ruined by scars, radiation, resection, and ostomies, then a gracilis myocutaneous flap33,34,35,36,37 is the next option, although not ideal due to its small volume and its pedicle does not allow adequate reach into the pelvis and sacrum. An additional flap such as pedicled omentum based on the right gastroepiploic vessel is necessary to fill the sacral dead space (Fig. 5).38 Finally, another regional choice such as a posterior thigh flap off the inferior gluteal artery is useful when the above flaps not available.39

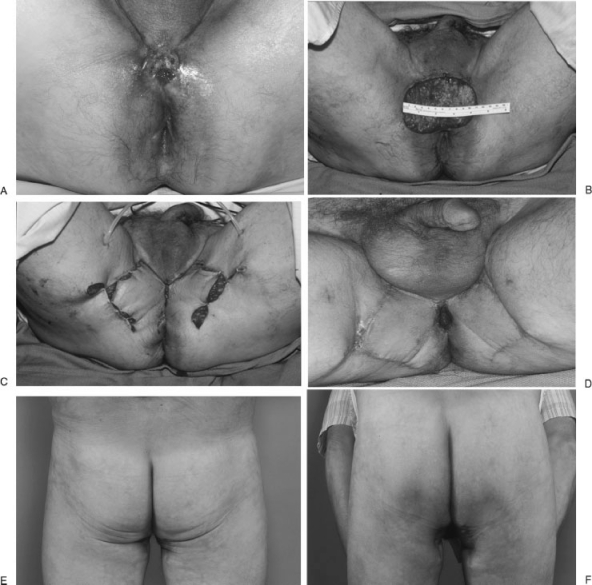

Figure 4.

Vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (VRAM) is an excellent option for perineal region in case of through and through perineal-pelvic defect from pelvic exenteration. A supraumbilical skin island over the rectus muscle provides excellent reach to pelvic and perineum while the deep inferior epigastric vascular bundle is the blood supply. This patient with hidradenitis suppurativa and recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the anus after prior resection and irradiation underwent an abdominoperineal resection. Surrounding perineal scars from hidradenitis suppurativa and irradiation made local flaps such as V-Y perineal flap or bilateral gluteal flaps not possible (last image, bottom panel). A VRAM served well in this scenario.

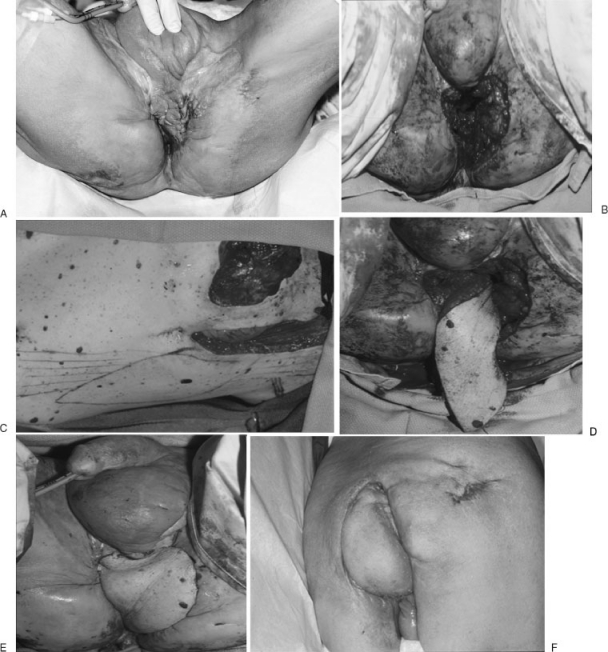

Figure 5.

When radical anterior and posterior pelvic exenteration combined with perineal, scrotal, perineal, and perianal skin resection leaves a large defect, the VRAM is an excellent choice. Ostomies or prior scars destroy the rectus abdominis blood supply; therefore, other options are necessary. This case of recurrent prostatic cancer post irradiation (external beam and seeds) required such radical resection including the pubic symphysis. Unfortunately, both rectus abdominis muscles were consumed by ureterostomy and colostomy. A pedicle omentum from the right gastroepiploic vessel allowed excellent reach to fill the pelvis. Meanwhile, an extended gracilis myocutaneous flap provide additional coverage and support for the reconstructed pelvic floor. Finally, remnant of surrounding skin allowed good color match to the close a very difficult problem. In standing position, patient had no pelvic hernia.

CONCLUSIONS

Whether infection or malignancy, static scrotal and perineal reconstruction is necessary to obtain wound healing. Adequate counseling with patients is critical to set realistic expectations because a scrotal reconstruction outcome will always fall short of the native dynamic scrotum. Skin graft and bulky flap reconstruction of total scrotum may interfere with spermatogenesis. For malignancies, advanced planning on resection and reconstruction must be discussed with the multidisciplinary team to optimize immediate reconstruction outcome. Primary closure is preferred because it provides excellent color match and possible dynamic function of the scrotum. Otherwise, local and regional flaps are often adequate. VRAM is the workhorse for this area. When it is not possible, a pedicled gracilis myocutaneous flap and omentum together are the second choice. Perforator flap advancement will bring additional flap options to manage defects in the perineoscrotal area.

References

- Jung A, Schuppe H C. Influence of genital heat stress on semen quality in humans. Andrologia. 2007;39(6):203–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werdelin L, Nilsonne Å. The evolution of the scrotum and testicular descent in mammals: a phylogenetic view. J Theor Biol. 1999;196(1):61–72. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson D E, Abbott R M, Levy A D, Sherman P M. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2002;22(3):543–561. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma06543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson R B, Singh A K, Novelline R A. Fournier gangrene: role of imaging. Radiographics. 2008;28(2):519–528. doi: 10.1148/rg.282075048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghan R J, Al-Jaberi T M, Bani-Hani I. Fournier's gangrene: changing face of the disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(9):1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/BF02237442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAninch J W, Kahn R I, Jeffrey R B, Laing F C, Krieger M J. Major traumatic and septic genital injuries. J Trauma. 1984;24(4):291–298. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradway C, Rodgers J. Evaluation and management of genitourinary emergencies. Nurse Pract. 2009;34(5):36–43. quiz 43–44. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000350569.68976.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelli-Schellpfeffer M, Gerber G S. The use of hyperbaric oxygen in urology. J Urol. 1999;162(3 Pt 1):647–654. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199909010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gencosmanoğlu R, Bilkay U, Alper M, Gürler T, Cağdaş A. Late results of split-grafted penoscrotal avulsion injuries. J Trauma. 1995;39(6):1201–1203. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199512000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Wei Z, Sun G, Luo Z. Thin-trimming of the scrotal reconstruction flap: long-term follow-up shows reversal of spermatogenesis arrest. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(11):e455–e456. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Zheng H, Deng F. Spermatogenesis after scrotal reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56(5):484–488. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Flanagan A M. Mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53(10):742–749. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N J, Torno R, Sorra T. Extramammary Paget's disease. South Med J. 2000;93(7):713–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutze W P, Gleysteen J J. Perianal Paget's disease. Classification and review of management: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(6):502–507. doi: 10.1007/BF02052147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechner S A. Common skin disorders of the penis. BJU Int. 2002;90(5):498–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T. Update on genital lesions. JAMA. 2003;290(8):1001–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson P. Testicular, prostate and penile cancers in primary care settings: the importance of early detection. Nurse Pract. 1991;16(11):18–20. 23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J L, Morgan T M, Lin D W. Primary scrotal cancer: disease characteristics and increasing incidence. Urology. 2008;72(5):1139–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham N LY, Pan W R, Rozen W M, et al. The pudendal thigh flap for vaginal reconstruction: optimising flap survival. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(5):826–831. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee J T, Joseph V T. A new technique of vaginal reconstruction using neurovascular pudendal-thigh flaps: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(4):701–709. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198904000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold P G, Lovich S F, Pairolero P C. Muscle flaps in irradiated wounds: an account of 100 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(2):324–327. discussion 328–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S H, Rudolph R. Healing in the irradiated wound. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17(3):503–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribaz J J, Chan R K. Where do perforator flaps fit in our armamentarium? Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(4):571–579. xi. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey A, Blondeel P N. Technical tips for safe perforator vessel dissection applicable to all perforator flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(4):593–606. xi–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Hasi W, Yang C, Song J. A microdissection study of perforating vessels in the perineum: implication in designing perforator flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63(6):665–669. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181999de3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Raffoul W, Piaget F, Egloff D V. Anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap in the difficult perineogenital reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):171–173. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neligan P C, Lannon D A. Versatility of the pedicled anterolateral thigh flap. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(4):677–681. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Sanger J R, Matloub H S, Gosain A, Larson D. Anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous island flaps in perineoscrotal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(2):610–616. discussion 617–618. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200202000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchel E W, Finical S, Johnson C. Pelvic reconstruction using vertical rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(1):22–26. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000099820.10065.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houvenaeghel G, Ghouti L, Moutardier V, Buttarelli M, Lelong B, Delpero J R. Rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in radical oncopelvic surgery: a safe and useful procedure. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(10):1185–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi B S, Nyam D C, Cheng C, Tan K C, Koo W H, Lee K S. Transpelvic rectus abdominis flap for perineal reconstruction following abdominal perineal resection with en bloc partial cystectomy and prostatectomy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Singapore Med J. 1999;40(10):654–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunesen K G, Buntzen S, Tei T, Lindegaard J C, Nørgaard M, Laurberg S. Perineal healing and survival after anal cancer salvage surgery: 10-year experience with primary perineal reconstruction using the vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) flap. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(1):68–77. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke T W, Morris M, Roh M S, Levenback C, Gershenson D M. Perineal reconstruction using single gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57(2):221–225. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S H, Hentz V R, Wei F C, Chen Y R. Short gracilis myocutaneous flaps for vulvoperineal and inguinal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(2):372–377. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199502000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M T, Bell J L, Chun J T. Perineal hernia repair using gracilis myocutaneous flap. South Med J. 1997;90(1):75–77. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199701000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persichetti P, Cogliandro A, Marangi G F, et al. Pelvic and perineal reconstruction following abdominoperineal resection: the role of gracilis flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(2):168–172. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000252693.53692.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata D, Hyland W, Busse P, et al. Immediate reconstruction of the perineal wound with gracilis muscle flaps following abdominoperineal resection and intraoperative radiation therapy for recurrent carcinoma of the rectum. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6(1):33–37. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman C S, Sherrill M A, Halvorson E G, et al. Utility of the omentum in pelvic floor reconstruction following resection of anorectal malignancy: patient selection, technical caveats, and clinical outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):559–562. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181ce3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J D, Reece G R, Eldor L. The utility of the posterior thigh flap for complex pelvic and perineal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(1):146–155. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181da8769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]