Abstract

Objective

To measure the influence of varying mortality time frames on performance rankings among regional NICUs in a large state.

Study design

We carried out cross-sectional data analysis of VLBW infants cared for at 24 level 3 NICUs. We tested the effect of four definitions of mortality: (1) deaths between admission and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days; (2) deaths between 12 hours of age and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days; (3) deaths between admission and 28 days; and (4) deaths between 12 hours of age and 28 days. NICUs were ranked by quantifying their deviation from risk-adjusted expected mortality and splitting them into three tiers: top six, bottom six, and in-between.

Results

There was wide inter-institutional variation in risk-adjusted mortality for each definition (observed minus expected Z-score range, -6.08 to 3.75). However, mortality-rate-based NICU rankings, and their classification into performance tiers, were very similar for all institutions for each of our time frames. Among all four definitions, NICU rank correlations were high (>0.91). Few NICUs changed relative to a neighboring tier with changes in definitions, and none changed by more than one tier.

Conclusion

The time frame used to ascertain mortality had little effect on comparative NICU performance.

Keywords: Infant, newborn, quality of care, performance measurement, mortality

Similar to outcomes of patients in other areas of medicine, premature infants cared for in NICUs experience variations in quality of health care and clinical outcomes that cannot readily be explained by differences in underlying clinical risk (1–7). For example, risk-adjusted mortality rates among NICUs participating in the Vermont Oxford Network (VON) show up to a three-fold difference (6).

Health policy-makers and health care payers are promoting comparative performance assessments in order to improve the value of health care (8, 9). Many clinicians are wary of this competitive model of quality-improvement; one concern is whether the data will allow for valid comparisons among providers (10).

Studies assessing adult inpatient quality of care have shown that standardized mortality rates for congestive heart failure based on in-hospital and 30-day mortality may be relatively similar, despite differing discharge practices and rates (11). One study did not yield markedly different results when using data from 30 days versus 180 days post-admission. Moreover, according to the 180-day data, the 30-day data are good predictors of the best and worst quintile of hospitals (12). However, others have found that general in-hospital mortality rates differed widely according to the method of evaluation (13).

In the NICU setting, the time frame used to ascertain mortality has been variably defined, depending on expert input and properties of available data repositories. Public stakeholders and neonatal quality of care collaboratives have applied different mortality definitions for comparative performance measurement. For example, the Joint Commission’s neonatal mortality measure focuses on neonates who expire before 28 days of age (14) – all live-born neonates are included, as are transfers-in (no limit set on the day of transfers). Transfers-out are excluded from this definition. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) indicator includes in-hospital deaths of infants that were born at that institution (inborn) and those that were transferred from another hospital (outborn) (15). Quality collaboratives have traditionally focused on death during the birth hospitalization.

Differences in these definitions may influence provider performance. For example, inclusions of deaths after day of life 28 but before discharge, although uncommon, may highlight opportunities for improvement in chronic respiratory care or health care maintenance, including the avoidance of late infections. The effect of certain definitions on comparisons of provider performance must be made explicit in order to draw appropriate and relevant conclusions supporting care improvement. This paper examines the effects of changes in measurement and sample definitions of mortality (i.e. the time frame used to ascertain mortality) on NICU performance ratings.

Methods

This study uses data from the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative (CPQCC). The Collaborative includes more than 100 member hospitals, including all of the state’s 24 regional centers. The CPQCC maintains a real-time, risk-adjusted perinatal data system. Measurement bias is addressed through standardized data collection procedures. Data are abstracted from the medical record locally, using data abstraction protocols. The data are then transmitted to CPQCC, where they are subjected to logic and completeness checks. In the event of inconsistencies, the data are reconciled with the medical record.

We tried to minimize selection bias by using exclusion criteria, depicted in Table I (available at www.jpeds.com), designed to minimize exclusion of patients from the database; minimize systematic bias from discretionary care decisions at the border of viability; maximize comparability across NICUs by defining a clinically homogenous patient population; and ensure clinical outcomes of care were attributed to the NICU under investigation.

Table 1.

Exclusion Criteria and Rationale

| Exclusion Criterion | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Transfer out for reasons other than convalescent care | Minimize exclusion of patients, maximize information content |

| GA < 25 weeks | Minimize systematic bias at the border of viability |

| BW < 1,500 grams | Maximize comparability across NICUs |

| Major congenital anomalies | Maximize comparability across NICUs |

| Transfer in after 3 days of age* | Minimize falsely ascribing responsibility for mortality to NICU under evaluation |

| Delivery room deaths | Minimize systematic bias from effect of perinatal care and differences in ascertainment |

This variable was defined as after 1 day of age in sensitivity analysis, see text

Our study sample included infants with a birth weight of less than 1,500 grams and a gestational age of at least 25 weeks. The upper limit weight cut-off is congruent with inclusion criteria into the CPQCC small infant database and harmonized with other measures of quality endorsed by the National Quality Forum (16). With regard to including infants at the border of viability, we based our criteria on a study which highlighted that 84% of surveyed neonatologists considered treatment clearly beneficial for infants born above 25 weeks gestational age. Only 41% considered treatment beneficial at 24 1/7–6/7 weeks gestation, highlighting the potential bias introduced by inclusion of this group in our analyses (17). Using standard CPQCC definitions, we excluded patients with major congenital anomalies (those associated with an increased mortality risk), because we were interested in examining mortality among a “healthy” preterm population. Infants who remained in the hospital beyond one year of life were excluded because data collection is truncated at that age and survival is uncertain.

Patient Transfer

Data from the CPQCC database used for this study were collected at the patient-level but not at hospital level. This made it difficult to confidently attribute responsibility for certain outcomes to individual institutions for transferred patients. We considered two main time-periods for transfers: early transfer-in and late transfer-out. The timing of early transfer-in cases depends on whether the transferring facility intended immediate post-partum neonatal transfer due to unavailability of adequate neonatal intensive care support, or whether infants receive a trial of therapy in the hope of retaining care locally. We excluded infants admitted beyond three days of age (day one being the day of birth) to avoid penalizing (or crediting) institutions for the quality of care delivered at the transferring institution.

Among transferred infants, the location of a clinical event was not recorded in the database. Transfer out of moribund infants may introduce bias but was minimized in this analysis through our focus on regional centers. We therefore included infants transferred out for convalescent care (85% of those transferred out). Deaths among this group were rare, and arguably the regional centers, to whom these deaths were attributed, assume some degree of responsibility by sending an infant to a partner institution for convalescent care.

In infants that were transferred for other reasons (predominantly for medical services, diagnostic imaging, or surgery) it may be difficult to confidently attribute responsibility for death to the receiving or transferring institution. We therefore omitted these infants from the analysis.

Sample

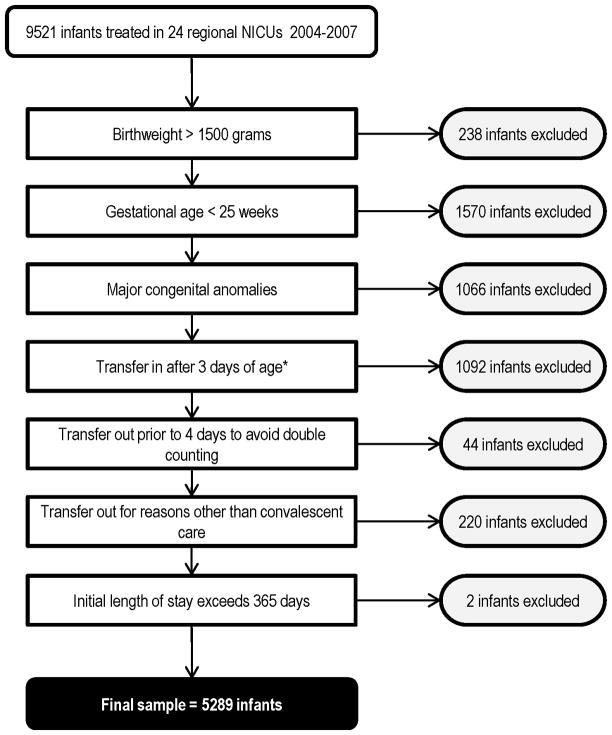

5,289 VLBW infants cared for at all of California’s 24 level 3 regional centers between 2004 and 2007 met the inclusion criteria. Of these centers, fifteen are designated as level 3D based on the fact that they perform open-heart surgery and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for medical conditions. The remaining nine are classified as level 3C (subspecialty neonatal intensive care units with extensive capabilities except open-heart surgery or ECMO) (18). Five regional centers did not have birthing facilities on site. We used multiyear analysis because there was a small number of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants cared for at some of the institutions. Figure 1 shows the number of excluded infants by criterion.

Figure 1.

Patient sample and exclusions.

Dependent variables - Mortality

We used four competing time frames to ascertain mortality, presented in order of decreasing inclusivity ( Figure 2). All time frames refer to the birth hospitalization and include the time after transfer: (1) deaths between admission and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days; (2) deaths between 12 hours of age and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days; (3) deaths between admission and 28 days; and (4) deaths between 12 hours of age and 28 days.

Figure 2.

Four competing definitions of mortality. NICU - neonatal intensive care unit, dc - discharge, d - days, h - hours.

We set the early cut-off for inclusion into this study to NICU admission or 12 hours of life. This time difference represents potential bias due to admission of moribund patients that are admitted for comfort care but expected to die imminently.

We excluded delivery room deaths from mortality definitions due to concerns regarding validity and reliability: validity because neonatal providers may not be responsible for the delivery room death of a moribund infant; reliability because there may be local practice variation in designating infants as delivery room versus fetal deaths. Delivery room deaths were defined as any eligible infant who died in the delivery room or at any other location in the hospital within 12 hours after birth or prior to admission to the NICU. Fetal deaths are not recorded in the database. Data regarding mortality after the birth hospitalization were not available.

Independent variables

We applied CPQCC standard operational definitions for all independent variables. Statistical modeling for this analysis required transformation of continuous variables into categorical ones. Therefore, we stratified gestational age at birth into the following groups: 25 0/7 – 27 6/7, 28 0/7 – 29 6/7, and 30 0/7 or more weeks, based on similar patient numbers between groups. Gestational age was assigned based on best obstetrical estimate and, if unavailable, on best neonatal assessment. Prenatal care was defined as any prenatal obstetrical care prior to the admission during which birth occurred. Neonates with birth weight less than 10th percentile were considered small for gestational age. Apgar score was categorized as three or below, between four and six, and above six.

Analyses

Hospital-level data included each level 3 NICU as the unit of analysis. In order to adjust for confounding variables, we developed a risk-adjustment model based on “Definition 1”, as this definition was the most inclusive. We tested a set of candidate variables associated with mortality in univariate analyses, using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Based on the underlying variable distribution, we used the t-test or the two-sample Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Variables associated at a significance level of p ≤ 0.25 were entered into a logistic regression model and variables associated at a significance level of p > 0.05 were successively removed from the model after checking the log likelihood ratio test for contribution to model fit. The resulting model included the following variables: outborn, small for gestational age, gestational age, sex, five-minute Apgar score, cesarean delivery, and prenatal care. Multiple birth was not associated with mortality in univariate analysis, but when we added it to the model based on the extant literature (19), it had statistical significance. We therefore retained it in the model. A logistic regression based on these variables had a c-statistic of 0.82.

Adding race/ethnicity variables to the model did not improve model discrimination

We used a methodology developed for use in the United Kingdom educational system but relevant and valid in any profiling setting with dichotomous outcomes (20). For each NICU and for each definition of mortality, a z-score was computed as observed minus expected divided by standard error. The NICU’s expected value was computed as a weighted average of the mortality rate in the overall database for all levels of the risk adjustment variables. We ranked NICUs according to the deviation from expected mortality rates and classified them into three tiers: top six, bottom six, and in-between. We assessed similarity in the results from the four definitions of mortality using the correlations and rank correlations of the z-scores.

In sensitivity analyses we evaluated the effect of other variations in inclusion criteria on NICU rankings, by including delivery room deaths and by restricting transfers in to the first day of life. In addition, we evaluated the effect of race/ethnicity on mortality by adding variables for ethnicity (Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Asian, and other) to the models. Finally, we examined the effect of using only one year of data for analysis because this may result in less stable estimates. For all analyses, we considered two-sided p values of less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

This study was approved by the CPQCC and the Baylor College of Medicine IRB.

Results

Table II shows the results from descriptive analyses of our sample population. Most deaths occurred by 28 days and only four deaths occurred after transfer. Table III (available at www.jpeds.com) shows the timing of death by NICU in more detail and highlights that most deaths occurred between 12 hours and 28 days.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Infants and NICUs

| Characteristic | n (%) or mean (SD) | Range of proportions/means among NICUs |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (n=5,289; range 10 – 628) | ||

| Deaths before 12 hours of life | 32 (0.6) | 0 – 9.1 |

| Deaths after 12 hours and before 28 days of life | 217 (4.1) | 0 – 28.6 |

| Deaths between 28 days and 366 days of life * | 62 (1.2) | 0 – 7.1 |

| Infants transferred out | 1046 (19.8) | 0 – 70.5 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 28.5 (2.42) | 26.7– 29.2 |

| Birthweight (grams) | 1093 (259) | 920 – 1160 |

| Female | 2590 (49.0) | 9.1 – 80.0 |

| Apgar Score at 5 minutes | 6.6 (1.2) | 5.9 – 6.8 |

| Cesarean delivery | 3868 (73.2) | 52.4 – 86.3 |

| Multiple gestation | 1600 (30.3) | 9.1 – 44.3 |

| Outborn | 1579 (29.9) | 2.4 – 30.7** |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-hispanic white (reference) | 1690 (32.0) | 0 – 46.2 |

| Non-hispanic black | 635 (12.0) | 0 – 40.0 |

| Hispanic | 2242 (42.4) | 18.8 – 100 |

| Asian | 576 (10.9) | 0 – 31.1 |

| Other | 146 (2.8) | 0 – 32.6 |

among infants still hospitalized, NICUs (k=24),

excluding five hospitals all infants were outborn

Table 3.

Timing of Death by NICU, n (%)**

| NICU | npatients | DR | <12h of life* | 12h to 28d | 29d to 366d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 628 | 0 | 5 (0.8) | 17 (2.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| B | 288 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| C | 183 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) |

| D | 98 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| E | 196 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.6) | 0 |

| F | 87 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| G | 266 | 0 | 0 | 12 (4.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| H | 83 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.4) | 0 |

| I | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| J | 42 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.8) | 0 |

| K | 344 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 15 (3.8) | 6 (1.7) |

| L | 500 | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) | 16 (3.2) | 9 (1.8) |

| M | 148 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 6 (4.1) | 2 (1.4) |

| N | 395 | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 15 (3.8) | 4 (1.0) |

| O | 214 | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (3.7) | 3 (1.4) |

| P | 485 | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | 24 (4.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| Q | 202 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 10 (5.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| R | 352 | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 20 (5.7) | 6 (1.7) |

| S | 80 | 0 | 0 | 7 (8.8) | 2 (2.5) |

| T | 273 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 12 (4.4) | 6 (2.2) |

| U | 186 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 10 (5.4) | 5 (2.7) |

| V | 132 | 0 | 0 | 17 (12.9) | 0 |

| W | 86 | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 8 (9.3) | 4 (4.7) |

| X | 11 | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (9.1) |

|

| |||||

| % of deaths | 4.9 | 9.8 | 66.4 | 19.1 | |

after admission to NICU, DR – delivery room; note that DR deaths are excluded from comparisons of different definitions of mortality tested in this manuscript

percentages are row percentages, which do not add to 100 because surviving infants are excluded

Risk-adjusted mortality varied significantly between NICUs. In fact, NICU site was a significant independent predictor of mortality for all definitions. Figure 3 (available at www.jpeds.com) highlights large between NICU differences in risk-adjusted mortality odds (mean z-score range −5.75 to 3.75). In comparison, within NICU variation, shown as the range of mortality estimates across the four definitions, was less prominent.

Figure 3.

Risk-adjusted observed minus expected mortality z-scores, by hospital, across the four definitions of mortality. The bars do not represent confidence intervals but show the mean and range of z-scores. A lower z-score indicates lower-than-expected mortality. The dotted lines represent two standard deviations below or above expected performance.

Mortality rate-based NICU rankings and their classification into one of the three performance tiers were very similar and highly correlated (rho > 0.93) across all four definitions of mortality (Table IV). NICU rankings changed little in response to the inclusion of deaths within the first 12 hours which represented less than 10% of all deaths during the birth hospitalization (definitions 1 and 2). One pair of the NICUs moved between the middle and bottom tiers (NICUs 18 and 20). However, some rankings were sensitive (improved or worsened) to the exclusion of deaths after 28 days (definitions 3 and 4), which accounted for nearly 20% of deaths during the birth hospitalization. Comparing definitions 1 and 3, two pairs of NICUs changed between tiers (NICUs 6 and 10 and NICUs 18 and 21). Across all definitions, few NICUs changed into a neighboring tier and none changed by more than one tier.

Table 4.

Hospital Performance Across the Four Definitions of Mortality

| NICU | Definition 1 Rank |

Definition 2 Rank (%Δ*) |

Definition 3† Rank (%Δ*) |

Definition 4† Rank (%Δ*) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Tier | A | 1 | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| B | 2 | 2 (0.0) | 3 (−4.2) | 2 (0.0) | |

| C | 3 | 3 (0.0) | 2 (+4.2) | 3 (0.0) | |

| D | 4 | 6 (−8.3) | 4 (0.0) | 4 (0.0) | |

| E | 5 | 4 (+4.2) | 10 (−20.8) | 8 (−12.5) | |

| F | 6 | 5 (−4.2) | 5 (+4.2) | 5 (+4.2) | |

| G | 7 | 9 (−8.3) | 11 (−16.7) | 15 (−33.3) | |

| H | 8 | 7 (+4.2) | 7 (+4.2) | 9 (−4.2) | |

| I | 9 | 8 (+4.2) | 6 (+12.5) | 6 (+12.5) | |

| J | 10 | 10 (0.0) | 14 (−16.7) | 13 (−12.5) | |

| K | 11 | 12 (−4.2) | 8 (+12.5) | 10 (+4.2) | |

| L | 12 | 14 (−8.3) | 9 (−12.5) | 7 (+20.8) | |

| M | 13 | 15 (−8.3) | 13 (0.0) | 12 (+4.2) | |

| N | 14 | 13 (+4.2) | 16 (−8.3) | 14 (0.0) | |

| O | 15 | 11 (+16.7) | 12 (+12.5) | 11 (+16.7) | |

| P | 16 | 16 (0.0) | 21 (−20.8) | 21 (−20.8) | |

| Q | 17 | 17 (0.0) | 15 (+8.3) | 16 (+4.2) | |

| R | 18 | 19 (−4.2) | 17 (+4.2) | 19 (−4.2) | |

| Bottom Tier | S | 19 | 20 (−4.2) | 18 (+4.2) | 18 (+4.2) |

| T | 20 | 18 (+8.3) | 19 (+4.2) | 17 (+12.5) | |

| U | 21 | 21 (0.0) | 20 (+4.2) | 20 (+4.2) | |

| V | 22 | 22 (0.0) | 24 (−8.3) | 22 (0.0) | |

| W | 23 | 23 (0.0) | 22 (+4.2) | 24 (−4.2) | |

| X | 24 | 24 (0.0) | 23 (+4.2) | 23 (+4.2) | |

|

| |||||

| npts/ndeaths | 5289/311 | 5257/249 | 5273/279 | 5241/217 | |

Note that because mortality is an uncommon event, NICUs with small n (such as NICU I or J) are relegated to the middle tier, even with zero deaths. Definitions:

1 – Deaths between admission and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days

2 – Deaths between 12 hours of age and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days

3 – Deaths between admission and 28 days

4 – Deaths between 12 hours of age and 28 days

pts– patients

% rank change in comparison to Definition 1

Average % rank change in comparison to Definition 1 significantly greater in middle NICUs than top/bottom tiers (p<0.05)

Performance among NICUs in the top and the bottom tiers was more stable than among those in the middle tier. Differences in mortality among NICUs in the middle tier were smaller in comparison with the extremes, generating an inverted S-shaped curve (Figure 3). Middle tier NICUs occupy the “flat part” of the curve where they are more susceptible to variability in ranks. On the other hand, the high and low mortality tiers occupy the “steeper” parts of the curve, making a change in rank or tier classification less likely.

Sensitivity analyses, in which we included delivery room deaths; excluded infants that were transferred in after the first day of life; and included race as a potential confounder, were highly correlated with Definition 1 (Deaths between admission and end of birth hospitalization or up to 366 days, rank correlation > 0.97). Restriction of the sample to 2007 data did not significantly change our conclusions (data available upon request).

Discussion

This study examined the effect of varying time frames in the definition of mortality on NICU performance ratings. We demonstrated significant risk-adjusted variation in mortality between California’s 24 regional centers. However, we found that variation across the four mortality definitions had little effect on NICU performance. At most, two NICUs would have changed their classification as a top- or bottom-tier performer. Although these changes may have important implications for the affected NICUs, the striking part of this study was the high degree of agreement of NICU performance across the four definitions of mortality.

Even though ranks at either extreme of performance were quite stable, NICUs in the middle tier demonstrated larger changes in ranks. An inverted S-shaped pattern of provider performance (Figure 3) has been found by others (21). Our findings imply that evaluators may assert confidence in assessing extreme, but not average performance. This calls into question the utility and interpretation of widely-used league tables such as the U.S. News & World Report (22). Year-on-year rank changes in the middle section of a league table should be interpreted cautiously, as they may be caused by random fluctuations. In addition, although a strategy of focusing on bottom and top providers may seem appealing and mathematically more defensible, it may be inefficient for guiding improvement on a population scale. We recently demonstrated that a focus on moving mean performance yields significantly greater benefit than a focus on outliers (23).

Differences in defining inclusion and exclusion criteria arise from concerns about introducing systematic bias in mortality rate calculations and, consequently, misclassifying providers as outliers. In this study, we found little movement in provider rankings in response to inclusion or exclusion of deaths before 12 hours of life. Therefore, a theoretical argument to include deaths before 12 hours to capture potentially sub-standard neonatal care (24) has little practical relevance to comparative performance assessments.

We demonstrated somewhat more substantial movements in ranks among variations in definitions between 28 day and 365 days of life. Rationales can be presented for the adoption of either measure. Parsimony supports the 28-day mortality measure, especially because the majority of infants die within the first two weeks of life (25). In addition, this definition aligns with standard public health measures.

Conversely, this approach may be biased and obscure interesting insights into underlying care differences between NICUs. To illustrate, late neonatal deaths may occur due to care practices that result in prolonged dependence on invasive care, such as slow weaning off ventilators and/or slow feeding advances. This may result in greater incidence of late infections and subsequent mortality. In addition, there may be systematic differences in how readily NICUs withdraw life support when a poor outcome is anticipated (26). NICUs that tend to continue life support in such infants may have comparatively fewer deaths before 28 days of age but more thereafter, when these infants succumb to the sequelae of their conditions. In a related study, a panel of neonatal experts and a sample of clinicians preferred a measure based on in-hospital mortality (27, 28), our findings support the adoption of either definition.

Our results must be viewed within the context of our observational study design which is subject to bias and confounding. We sought to limit biases through careful selection of our sample. Although this is appropriate for comparative performance measurements, it may have decreased within-NICU variability. Sicker patients, such as those younger than 25 weeks gestational age, require increasing levels of therapeutic excellence to ensure survival. By excluding these infants, we may have diminished our ability to find NICUs that deliver truly exceptional care.

One of the strengths of our analysis is that CPQCC data mirror those of the Vermont Oxford Network, which has over 900 member NICUs worldwide, such that our study may generalize to “regional centers” in other states. Generalizability to lower level NICUs is tempered by the increased transfer bias generated by their inclusion. Future analyses will need to address these constraints. Although it is unclear whether our results generalize to other health care settings, our methods could be applied widely to improve the transparency of comparative performance measurement.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Veterans Administration Center t (VA HSR&D CoE HFP90-20). J.P. is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23 HD056298), and L.P. was a recipient of the American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (0540043N). The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Abbreviations

- CPQCC

California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative

- DR

delivery room

- GA

gestational age

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- VLBW

very low birthweight

- VON

Vermont Oxford Network

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Eichenwald EC, Blackwell M, Lloyd JS, Tran T, Wilker RE, Richardson DK. Inter-neonatal intensive care unit variation in discharge timing: influence of apnea and feeding management. Pediatrics. 2001;108:928–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escobar GJ, McCormick MC, Zupancic JAF, Coleman-Phox K, Armstrong MA, Greene JD, et al. Unstudied infants: outcomes of moderately premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:F238–F244. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.087031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Lewit EM, Rogowski J, Shiono PH. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with variation in 28-day mortality rates for very low birth weight infants. Vermont Oxford Network Pediatrics. 1997;99:149–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SK, McMillan DD, Ohlsson A, Pendray M, Synnes A, Whyte R, et al. Variations in practice and outcomes of the Canadian NICU Network 1996–7. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1070–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Profit J, Zupancic JA, McCormick MC, Richardson DK, Escobar GJ, Tucker J, et al. Moderately premature infants at Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in California are discharged home earlier than their peers in Massachusetts and the United Kingdom. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006;91:245–50. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.075093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogowski JA, Staiger DO, Horbar JD. Variations in the quality of care for very-low-birthweight infants: implications for policy. Health Aff. 2004;23:88–97. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankaran K, Chien L-Y, Walker R, Seshia M, Ohlsson A, Lee SK. Variations in mortality rates among Canadian neonatal intensive care units. Cmaj. 2002;166:173–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersen LA, Woodard LD, Urech T, Daw C, Sookanan S. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:265–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Profit J, Zupancic JA, Gould JB, Petersen LA. Implementing pay-for-performance in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;119:975–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholle SH, Roski J, Adams JL, Dunn DL, Kerr EA, Dugan DP, et al. Benchmarking physician performance: reliability of individual and composite measures. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:833–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal GE, Baker DW, Norris DG, Way LE, Harper DL, Snow RJ. Relationships between in-hospital and 30-day standardized hospital mortality: implications for profiling hospitals. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1449–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnick DW, DeLong ER, Luft HS. Measuring hospital mortality rates: are 30-day data enough? Ischemic Heart Disease Patient Outcomes Research Team. Health Serv Res. 1995;29:679–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahian DM, Wolf RE, Iezzoni LI, Kirle L, Normand SL. Variability in the measurement of hospital-wide mortality rates. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2530–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Joint Commission. A Comprehensive Review of Development and Testing for National Implementation of Hospital Core Measures. Available from: URL: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/A_Comprehensive_Review_of_Development_for_Core_Measures.pdf.

- 15.National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC) Neonatal mortality: in-hospital death rate among inborn and outborn neonates. Available from: URL: http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov.

- 16.Main EK. New perinatal quality measures from the National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission and the Leapfrog Group. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:532–40. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332d1b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peerzada JM, Richardson DK, Burns JP. Delivery room decision-making at the threshold of viability. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stark AR American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1341–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zupancic JAF, Richardson DK, Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Lee SK, Escobar GJ, et al. Revalidation of the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology in the Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e156–e163. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draper D, Gittoes M. Statistical analysis of performance indicators in UK higher education. J R Stat Soc. 2004;167:449–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs R, Goddard M, Smith PC. How robust are hospital ranks based on composite performance measures? Med Care. 2005;43:1177–84. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185692.72905.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US News & World Report. US News Best Children’s Hospitals: Neonatology. 2012 Available from: URL: http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/pediatric-rankings/neonatal-care?page=1.

- 23.Profit J, Coles MC, Pietz K, Kowalkowski MA, Mei M, Gould JB, et al. Profiling NICUs using postmenstrual age at discharge: the effect of different metric definitions. 2011. p. E-PAS 1432.334. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould JB. Vital records for quality improvement. Pediatrics. 1999;103:278–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones HP, Karuri S, Cronin CM, Ohlsson A, Peliowski A, Synnes A, et al. Actuarial survival of a large Canadian cohort of preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotten CM, Oh W, McDonald S, Carlo W, Fanaroff AA, Duara S, et al. Prolonged hospital stay for extremely premature infants: risk factors, center differences, and the impact of mortality on selecting a best-performing center. J Perinatol. 2005;25:650–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Profit J, Gould JB, Zupancic JA, Stark AR, Wall KM, Kowalkowski MA, et al. Formal selection of measures for a composite index of NICU quality of care: Baby-MONITOR. J Perinatol. 2011;31:702–10. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalkowski M, Gould JB, Bose C, Petersen LA, Profit J. Do practicing clinicians agree with expert ratings of neonatal intensive care unit quality measures? J Perinatol. 2012 Jan 12; doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.199. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]