Abstract

Background

Momordica charantia (bitter gourd) is not only a nutritious vegetable but it is also used in traditional medical practices to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Experimental studies with animals and humans suggested that the vegetable has a possible role in glycaemic control.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mormodica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Search methods

Several electronic databases were searched, among these were The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, SIGLE and LILACS (all up to February 2012), combined with handsearches. No language restriction was used.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared momordica charantia with placebo or a control intervention, with or without pharmacological or non‐pharmacological interventions.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data. Risk of bias of the trials was evaluated using the parameters of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other potential sources of bias. A meta‐analysis was not performed given the quality of data and the variability of preparations of momordica charantia used in the interventions (no similar preparation was tested twice).

Main results

Four randomised controlled trials with up to three months duration and investigating 479 participants met the inclusion criteria. Risk of bias of these trials (only two studies were published as a full peer‐reviewed publication) was generally high. Two RCTs compared the effects of preparations from different parts of the momordica charantia plant with placebo on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. There was no statistically significant difference in the glycaemic control with momordica charantia preparations compared to placebo. When momordica charantia was compared to metformin or glibenclamide, there was also no significant change in reliable parameters of glycaemic control. No serious adverse effects were reported in any trial. No trial investigated death from any cause, morbidity, health‐related quality of life or costs.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence on the effects of momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Further studies are therefore required to address the issues of standardization and the quality control of preparations. For medical nutritional therapy, further observational trials evaluating the effects of momordica charantia are needed before RCTs are established to guide any recommendations in clinical practice.

Keywords: Humans; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/drug therapy; Glyburide; Glyburide/therapeutic use; Hypoglycemic Agents; Hypoglycemic Agents/therapeutic use; Metformin; Metformin/therapeutic use; Momordica charantia; Momordica charantia/chemistry; Phytotherapy; Phytotherapy/methods; Plant Extracts; Plant Extracts/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus

Mormordica charantia (bitter gourd or bitter melon) is a climbing perennial that is characterized by elongated, warty fruit‐like gourds or cucumbers and is native to the tropical belt. Although momordica charantia is commonly used in traditional medical practices, along with research suggesting its benefits for people with type 2 diabetes, the current evidence does not warrant using the plant in treating this disease. This review of trials found only four studies which had an overall low quality. Three trials showed no significant differences between momordica charantia and placebo or antidiabetic drugs (glibenclamide and metformin) in the blood sugar response. The duration of treatment ranged from four weeks to three months, and altogether 479 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus participated. No trial investigated death from any cause, morbidity, health‐related quality of life or costs. Adverse effects were mostly moderate, including diarrhoea and abdominal pain. However, reporting of adverse effects was incomplete in the included studies. There are many varieties of preparations of momordica charantia, as well as variations in its use as a vegetable. Further studies are needed to assess the quality of the various momordica charantia preparations as well as to further evaluate its use in the diet of diabetic people.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus Settings: Out‐patients Intervention: Momordica charantia Comparison: Placebo, glibenclamide or metformin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Momordica charantia | |||||

| Death from any cause | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

| Morbidity | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

| Adverse effects (Follow‐up: 4 to 12 weeks) | Not estimable | Not estimable | Not estimable | 479 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | 3 out of 4 studies reported some adverse effects |

| Health‐related quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

| Costs | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Not investigated |

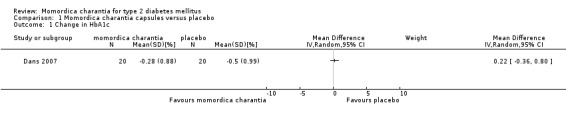

| Change in HbA1c from baseline to endpoint (Follow‐up: 3 months) | 0.2 (favouring placebo) | ‐0.4 to 0.8 | 40 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 incomplete reporting of adverse effects in studies, short time periods

2 one study with low number of participants

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion or insulin action, or both. A consequence of this is chronic hyperglycaemia (that is elevated levels of plasma glucose) with disturbances of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. The risk of cardiovascular disease is increased. For a detailed overview of diabetes mellitus, please see 'Additional information' in the information on the Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group in The Cochrane Library (see 'About', 'Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)'). For an explanation of methodological terms, see the main glossary in The Cochrane Library.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a global public health issue, particularly in older adults (Abegunde 2007; Wild 2004). The increase in the numbers of the younger population with T2DM is also a cause for concern due to the implication of pathogenic or accelerated aging changes at the molecular level and associated losses of function (Monnier 2005).

Description of the intervention

Mormordica charantia (bitter gourd or bitter melon) (MC), a member of the Cucurbitaceae family, is a climbing perennial that is characterized by elongated, warty fruit‐like gourds or cucumbers and is native to the tropical belt (Siemonsma 1997). The white or green unripe fruit changes to yellow or orange on ripening, and its characteristic bitter taste becomes more pronounced. This market vegetable is nutritionally rich in vitamins A, C and beta‐carotene, as well as minerals such as iron, and phosphorus and potassium.

Besides its presence having extended to the global culinary stage, this popular botanical specimen of the Asian‐Pacific, African and the Caribbean regions is an important resource for traditional medicine practices of many regions in the treatment of T2DM. The entire plant (that is, its seeds, fruit, leaves and roots) has also been used to treat dyslipidaemia, microbial infections and hypertension; to accelerate wound healing and inflammation; and as a laxative and emmenagogue.

How the intervention might work

The blood glucose‐lowering activities of MC have been consistently demonstrated in both animal studies (Chaturvedi 2005; Leatherdale 1981; Shetty 2005) and clinical trials (Ahmad 1999; Khanna 1981; Leatherdale 1981; Welihinda 1986). A number of bioactive phytochemical compounds have been isolated from it. Mechanisms of activity have been attributed to enhancement of beta‐cell integrity (Ahmed 1998; Singh 2007), promotion of insulin release (Fernandes 2007), insulin‐like activity (Cummings 2004), and extrapancreatic effects. The latter include the inhibition of glucose transportation at the brush border of the small intestine (Shetty 2005).

Furthermore, MC has been shown to improve carbohydrate metabolism in the liver of diabetic mice through the stimulation of enzymes of the glycolytic pathway (Rathi 2002a). The metformin‐ and sulphonylurea‐like glycaemic control activities (Rotshteyn 2004) of MC are also augmented with exercise (Miura 2004). In addition to glycaemic control, MC has been proposed to have protective effects on target organs by delaying nephropathy (Kumar 2008), neuropathy (Ahmed 2004), retinopathy (Srivastava 1987), gastroparesis (Grover 2002a) and cataract (Rathi 2002b), as well as atherosclerosis (Ahmed 2001; Chaturvedi 2005). The antilipaemic activity of MC extracts in animal studies has suggested inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity resulting in subsequent decreases in lipid absorption (Oishi 2007) and inhibition of membrane lipid peroxidation (Ahmed 2001).

The broad‐spectrum antimicrobial activity of MC (Braca 2008; Frame 1998; Ogata 1991; Omoregbe 1996; Yesilada 1999) may protect vulnerable diabetic individuals, as well as non‐diabetic people, against disease‐causing organisms that are prevalent in areas where this vegetable is popular. Although the protective mechanisms against all of these organisms have not been determined, the immune‐stimulating properties of MC in microbial infections (Cunnick 1990) and its prevention of viral penetration of the cell wall may be critical functions (Bourinbaiar 1996).

Therefore, in clinical terms, the aforementioned properties can lead to improvement of glycaemic control, insulin resistance and the associated hyperlipidaemia, as well as to the possibility of protection from infections and improved wound healing. Besides the direct effect of glycaemic control in delaying complications, there may be additional protective effects on target organs.

Adverse effects of the intervention

Hypoglycaemia has been the primary measure in both animal (Abd El Sattar El Batran 2006) and human studies (Leatherdale 1981; Srivastava 1993). The interpretation of human studies, however, has been limited by their weak methodology. Anecdotal cases of hypoglycaemic coma and convulsions in children were reported with bitter melon tea (Hulin 1988a; Hulin 1988b). This adverse effect was also potentiated by rosiglitazone (Nivitabishekam 2008), metformin and sulphonylureas (Tongia 2004). Besides the mild hypotensive response noted in rat studies (Ojewole 2006), the presence of vicine, a favism‐inducing glycosidic compound, in the seeds may put patients with glucose‐6‐phosphatase deficiency at risk (Dutta 1981). Finally, the abortifacient effects of raw fruits have cast doubt on the safety of their consumption during pregnancy (Chan 1984; Chan 1985; Chan 1986).

Why it is important to do this review

The Asian‐Pacific region is currently at the forefront of the type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) epidemic (Cockram 2000). Coping with the increased prevalence of T2DM and its related functional disabilities will exhaust resources due to the intensive requirements of quality care (Lee 2007; Selvin 2006). Controlling the disease and its complications must be prioritised to prevent these additional burdens on the individual, family and society (Waidmann 2000). Proper glycaemia control, which has been shown to reduce morbidities and prevent disabilities, is achieved by striking a balance between nutrition, physical activity, medication and psychosocial factors (UKPDS 37). Delaying or compressing these diabetes‐related morbidities may thus increase a patient’s years of health.

Traditionally, medical nutritional therapy for T2DM has emphasized diets that have low fat and high complex carbohydrate contents, as well as the need for appropriate portions of proteins, essential micronutrients, and minerals (Bantle 2008). Although there are over 600 culinary botanicals influencing insulin‐glucose metabolism reported in the published literature (Bailey 1989; Grover 2002b; Li 2004; Mukherjee 2006), there is no evidence to support recommendations to consume these specific foods in the management of T2DM in current mainstream medical practice.

In addition, drug‐nutrient interactions that can develop with the concurrent use of drugs may be underemphasized (Genser 2008). Failure to identify and properly manage drug‐nutrient interactions can result in serious adverse consequences, notably hypoglycaemia (Nivitabishekam 2008; Tongia 2004). Thus, the result of such treatment failures can aggravate the existing burden of care and compound the already escalating healthcare costs.

Although preliminary experimental animal model studies have implicated the influence of MC on glucose‐insulin metabolism in T2DM, knowledge gaps still exist in the translation of the adverse effects and efficacy of this botanical to the clinical arena. In addition to being an important nutritious food source, there are also many processed products and food supplements that contain MC or its extract and tout its benefit in diabetes management. Therefore, understanding this natural resource of the region will not only provide more accessible, flexible, and quality nutritional choices to the diabetic patients but also enable clinicians to improve the management of T2DM in these countries.

Given the prevalence of T2DM and the potentially serious outcomes of this disease, it is important to address the gaps in the literature. There has been no systematic review in the recent literature specifically on the clinical effects of momordica charantia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, this review attempts to identify the difficulties in interpretation of publication results on this subject in the clinical setting.

Objectives

To assess the effects of mormodica charantia on type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials.

Types of participants

Adults over 18 years, of either gender, who have type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the diagnostic criteria below. The exclusion criteria include patients younger than 18 years, and those with normal fasting blood glucose and postprandial glucose levels. Patients with concomitant endocrinopathy affecting their blood glucose levels were also excluded.

To be consistent with changes in the classification and diagnostic criteria of type 2 diabetes mellitus through the years, the diagnosis should have been established using the standard criteria valid at the time of the beginning of the trial (for example ADA 1997; ADA 1999; WHO 1980; WHO 1985; WHO 1998). Ideally, diagnostic criteria should have been described. If necessary, authors' definition of diabetes mellitus was used. Diagnostic criteria were planned to be subjected to a sensitivity analysis.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Any orally administered mono‐preparation of momordica charantia (MC) in any dose or form. This may be the sole intervention or given in combination with insulin, oral hypoglycaemic agents, or both.

Control

Placebo or no treatment with or without active medications, such as insulin, oral hypoglycaemic agents or other herbal or nutritional preparations.

Co‐interventions were considered if both arms of the randomised trial received similar interventions. Combination preparations of momordica charantia with other herbs were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Fasting blood glucose levels (FBG)

Glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)

Adverse effects (e.g. hypoglycaemia)

Secondary outcomes

Serum insulin

Insulin sensitivity (homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR))

Serum cholesterol

Body weight, body mass index

Renal profile, liver profile

Morbidity (both type 2 diabetes mellitus‐related morbidities and non‐related co‐morbidities; all cause morbidity)

Functional outcomes (both physical and cognitive functions)

Health‐related quality of life (HR‐QoL)

Well‐being

Costs

Covariates, effect modifiers and confounders

Self‐management and compliance with treatment

Co‐medication (any pharmacological agent used in the direct management of type 2 diabetes mellitus; pharmacological agents used in the management of diabetic and non‐diabetic related co‐morbidities)

Timing of outcome measurement

Both primary and secondary outcomes at four weeks or more were considered, with the exception of HbA1c. For this parameter trials needed to continue for over three months to yield meaningful results.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The initial search was carried out in November 2009 and the second updated searches were completed on 5 March 2012. The following database sources were used for the identification of trials:

The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2012);

MEDLINE (1950 to week 4 February 2012);

EMBASE (1980 to 29 February 2012);

Proquest Health and Medical Complete (until week 4 February 2012);

CINAHL (until week 4 February 2012);

BioMed Central gateway (until week 4 February 2012);

CAM on Pubmed (until week 4 February 2012);

Sportdiscus (until week 4 February 2012);

ISI Web of Knowledge (until week 4 February 2012);

Academic Onefile (until week 4 February 2012);

Health Technology Assessment (until week 4 February 2012);

AARP Ageline (until week 4 February 2012);

LILACS (www.bireme.br/bvs/I/ibd.htm) (until week 4 February 2012);

Natural medicines comprehensive database (until week 4 February 2012);

Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database (until week 4 February 2012);

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (until week 4 February 2012).

Theses:

Proquest Dissertations and Theses database (until week 4 February 2012).

Databases of ongoing trials:

UK

'Current Controlled Trials' (www.controlled‐trials.com ‐ with links to other databases of ongoing trials) and the National Research Register (http://www.update‐software.com/projects/nrr/);

USA

Clinical Trials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Studies published in any language were included. The search strategies for MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Proquest Medical and Health Complete are described. For detailed search strategies please see Appendix 1. There was a slight adaptation in the search strategy for the other databases.

Searching other resources

In addition, the electronic search was complemented by a manual search in medical libraries for recent relevant articles. Reference lists of retrieved articles of included trials and (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports were screened for additional trials. Further additional information, additional references, unpublished data and updated results of ongoing interventions were obtained by contacting content experts and associations. Similarly, manufacturers of processed products and food supplements that contain MC or its extract were contacted, if necessary.

No additional key words of relevance were detected during any of the electronic or other searches. Thus, the electronic search strategies were not modified.

In the case of duplicate publications and companion papers of a primary study, all the available information was reviewed. If necessary, authors of the respective papers were contacted to clarify any doubt. To maximise the yield of information, all available data were critically evaluated.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (CPO) discarded the irrelevant publications, based on the title of the publication and its abstract, from the search list. In the presence of any suggestion that an article could be relevant, it was retrieved for further assessment. All potentially relevant articles were investigated as full text for inclusion, from the culled citation list. Only four studies were selected. There were two independent assessments on the trials. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or in consultation with a third party. The influence of individual bias criteria was explored in a sensitivity analysis. Interrater agreement for key bias indicators (for example allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data) was calculated using the kappa statistic (Cohen 1960).

There were only four studies selected for this review. However, in the future the review will be updated as more reports and studies become available. If these studies are later on included, the influence of the primary choice will be subjected to a sensitivity analysis. In cases of disagreement, the rest of the group will be consulted and a judgement will be made based on consensus. If differences in opinion persist, they will by resolved by a third party. Where resolving disagreement is not possible, the article will be added to those 'awaiting assessment' and the authors will be contacted for clarification. An adapted PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flow‐chart of study selection is included (Liberati 2009) (Figure 1).

1.

Adapted PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flow‐chart of study selection.

Data extraction and management

For assessment of the risk of bias of included studies, methodological characteristics for the trials were entered in a table. Two independent assessments followed the criteria in templates (for details see 'Characteristics of included studies', Table 2 and Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5). When relevant information on the trial was unclear or missing, the original author of the study was contacted to obtain the required information. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by consultation with a third party.

1. Overview of study populations.

|

Characteristic Study ID |

intervention & control | [n] screened | [n] randomised | [n] safety | [n] ITT | [n] finishing study | [%] of randomised participants finishing study |

| Dans 2007 1 | I: momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents C: placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | ‐ | I: 20 C: 20 T: 40 |

I: 20 C: 20 T: 40 |

I: 20 C: 20 T: 40 |

I: 19 C: 20 T: 39 |

I: 95 C: 100 T: 98 |

| Fuangchan 2011 2 | I1: momordica charantia 500 mg/day I2: momordica charantia 1000 mg/day I3: momordica charantia 2000 mg/day C: metformin |

‐ | I1: 33 I2: 32 I3: 31 C: 33 T: 129 |

I1: 33 I2: 32 I3: 31 C: 33 T: 129 |

I1: 33 I2: 32 I3: 31 C: 33 T: 129 |

I1: 31 I2: 30 I3: 29 C: 30 T: 120 |

I1: 94 I2: 94 I3: 94 C: 91 T: 93 |

| John 2003 1 | I: momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents C: placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | ‐ | I: 26 C: 24 T: 50 |

I: 26 C: 24 T: 50 |

‐ | I: 22 C: 19 T: 41 |

I: 85 C: 79 T: 82 |

| Purificacion 2007 1 | I: momordica charantia C: glibenclamide | ‐ | I: 128 C: 132 T: 260 |

I: 128 C: 132 T: 260 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Total | all interventions | 270 | |||||

| all controls | 209 | ||||||

| all interventions & controls | 479 | ||||||

"‐" denotes not reported

1 no information how missing data were handled

2 last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was used for missing values

Abbreviations:

C: control; I: intervention; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; T: total

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

There were two independent assessments for each trial based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). Disagreements was resolved by consensus, or in consultation with a third party. The influence of individual bias criteria was explored in a sensitivity analysis. Interrater agreement for key bias indicators (for example allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data) was calculated using the kappa statistic (Cohen 1960). In cases of disagreement, the rest of the group was consulted and a judgement was made based on consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

Summary statistics for each trial were used. Each outcome was assumed to have a zero correlation between the measurements at the baseline and assessment times. This conservative approach is preferable in a meta‐analysis even though it has a tendency to overestimate the standard deviation of change from the baseline. The latest available assessment prior to randomisation, but no longer than two months before, or at randomisation was defined as the baseline assessment.

Data on every person assessed were examined for each outcome measure. In cases where individual patient data were not available, data from summary statistics were used.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, the number in each treatment group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest or endpoint of clinical relevance was examined. These were expressed as odd ratios (OR) or relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, the effect measure was the weighted mean difference when the pooled trials used the same rating scale or test to assess an outcome. Where the pooled trials used different rating scales or tests the standardized mean difference, that is the absolute mean difference divided by the standard deviation, was planned to be calculated. Accordingly, the mean change from the baseline, the standard deviation of the mean change, and the number of patients for each treatment group at each assessment were extracted. Where changes from the baseline were not reported, the mean, standard deviation, and the number of people in each treatment group at each time point were extracted, if available. Where the rating scales used in these trials had a reasonably large number of categories (more than 10), the data were treated as continuous outcomes arising from a normal distribution. All these outcomes were expressed within 95% CIs.

Time‐to‐event (survival) data

The timing of outcomes was planned to be expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CIs. This included participants likely or unlikely to experience an event in the intervention or control groups. The hazard ratio was assumed to be constant across the follow‐up period even though the hazards may vary continuously.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to take into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome.

Dealing with missing data

The potential impact of missing data depends on its magnitude, the pooled estimate of the treatment effect, and the outcome variability. If feasible, relevant missing data were sought from the respective authors. The number of participants enrolled, intention to treat (ITT) and treated or per protocol (PP) populations were evaluated in all eligible randomised controlled trials. Reasons for attrition, such as drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were examined. Finally, missing data and techniques to handle it were subjected to critical appraisal.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In future, when more reports and studies are available for selection, heterogeneity identified by visual inspection of the forest plots or the standard Chi2 test will be subjected to further evaluation. As these tests have characteristically low power, the significance level is set at P = 0.1. If heterogeneity is observed in the treatment effect between the trials, the I2 statistic will be used for confirmation of the presence of inconsistency between studies (Higgins 2002). I2 values of 50% and more indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). When heterogeneity is found, we will attempt to determine potential reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics (for example those studies with lower risk of bias).

Assessment of reporting biases

If sufficient randomised controlled trials are identified, the data will be examined for potential publication bias using a funnel plot. In view of the number of explanations for the asymmetry of a funnel plot (Sterne 2001) a careful approach to the statistical analyses, with discussions and consensus among the review authors, will be taken (Lau 2006).

Data synthesis

We planned to summarize data statistically if they were available, sufficiently similar and of sufficient quality.

The null hypothesis states that momordica charantia alone or in combination with insulin, oral hypoglycaemic agents, or both, for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients will yield no significant effects compared with placebo controls or with no intervention. Both parallel‐group trials and cross‐over trials that satisfy the eligibility criteria were considered. Data were analysed on an ITT basis. In the absence of ITT data, or where the number of drop‐outs was not relevant, the data of the treatment period were analysed and indicated as such. Statistical analyses were performed according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the newest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses if one of the primary outcome parameters demonstrated statistically significant differences between intervention groups. In any other case, subgroup analyses would be clearly marked as a hypothesis generating exercise. If there are sufficient studies, subgroup analyses will be performed based on the following:

studies with normal or below baseline nutritional status;

effect of dosage of MC on primary outcome measures;

effect of forms of MC on primary outcome measures;

effect of treatment and ingestion duration of MC on primary outcome measures.

Sensitivity analysis

If there are sufficient studies, sensitivity analyses will be performed to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analysis with exclusion of any unpublished studies;

repeating the analysis taking account risk of bias, as specified above;

repeating the analysis with exclusion of any very large studies or studies of long duration to establish how much they dominate the results;

repeating the analysis excluding studies using the filters diagnostic criteria, language of publication, publication status, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

The robustness of the results will be tested by repeating the analysis using different measures of effects size (relative risk, odds ratio, risk difference) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Results

Description of studies

In total, four randomised clinical trials (RCTs) were selected for further assessment (Dans 2007; Fuangchan 2011; John 2003; Purificacion 2007). Two trials reported random allocation of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus to momordica charantia capsules (Dans 2007) or tablets (John 2003) versus control. In both the controls were a placebo. One used riboflavine (John 2003) and the other did not provide details on the contents of the placebo (Dans 2007). The other RCT compared momordica charantia leaf tablet with glibenclamide (2.5 mg twice a day) (Purificacion 2007). Fuangchan 2011 used momordica charantia capsules as the interventions with metformin tablets in the control arm. The randomised trials are listed under ’Characteristics of included studies’; all the trials were published in English. Two studies were published in peer‐reviewed publications (Dans 2007; Fuangchan 2011).

Results of the search

The initial electronic searches identified 80 articles (Figure 1). The updated search of the above databases retrieved a total of 27 articles. Three additional references were retrieved for further assessment from the screening of reviews (Balwa 1977; Purificacion 2007; Rosales 2001). Ninety‐eight records remained after duplicates were removed. On reading the titles and abstracts, 90 of these articles were excluded because they were reviews, non‐clinical studies or had objectives that differed from those of this review. Four articles were excluded because they did not meet our inclusion criteria (Balwa 1977; Inayat‐ur‐Rahman 2009; Lim 2010; Rosales 2001). The reasons for exclusion are listed under ’Characteristics of excluded studies’.

Included studies

The included trials are summarised in Table 2, Appendix 4 and Appendix 2. A total of 479 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were randomised in four trials: ranging from 40 to 260 patients per trial (Dans 2007; Fuangchan 2011; John 2003; Purificacion 2007). Two trials included out‐patients (Dans 2007; John 2003) and no information was provided in the remaining two trials (Fuangchan 2011; Purificacion 2007). There was no information on the ethnic groups in all four trials. Three of the randomised clinical trials provided data of mean age above 50 years (Dans 2007; Fuangchan 2011; John 2003) while the fourth trial did not provide any data on this parameter (Purificacion 2007). The female:male ratio varied in all the four trials: 5:3 (Dans 2007), 3:1 (Fuangchan 2011), 17:8 (John 2003), and 1.4:1 (Purificacion 2007). Criteria for diagnosis were based on the authors’ definitions in three trials (Dans 2007; John 2003; Purificacion 2007) while the recommendations of ADA (ADA 2006) were used in the trial of Fuangchan 2011. The momordica charantia used for the interventions in the trials were capsules or tablets prepared from different components of the momordica charantia plant. One trial used tablets preparation from the leaves (Purificacion 2007), another used tablets prepared from shade‐dried whole fruit (John 2003), the third trial used capsules prepared from oven‐dried fruit pulp (Fuangchan 2011), whereas the remaining trial used capsules prepared from the plant fruits and seeds (Dans 2007). The control interventions used were placebo in two trials (Dans 2007; John 2003) and metformin and glibenclamide tablets, respectively, in the remaining two trials (Fuangchan 2011; Purificacion 2007). Riboflavine was used as placebo in one trial (John 2003). However, no information was provided about the content of the placebo of the trial of Dans 2007. The duration of treatment ranged from four weeks to three months.

Excluded studies

Two studies were excluded (Balwa 1977; Rosales 2001). The trials of Balwa 1977 and Inayat‐ur‐Rahman 2009 were experimental studies and there was no randomised allocation of participants. The duration of the intervention in the latter trial was short consisting of only three meals in 24 hours. Even though the trial of Rosales 2001 compared ampalaya tea (dried fruits with seeds) and camelia sinesis (commercially available tea), it was an open label, cross‐over trial with no randomisation. Although the study of Lim 2010 was a randomised, double‐blind, controlled trial, the intervention was a single dose of momordica charantia extracts.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on study populations, numbers randomised, analysed, intention to treat (ITT) and safety population, see Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

All the trials were of parallel‐group design. Recruitment of patients was limited to the centres of the study in two trials (Dans 2007; John 2003). There were also pre‐trial estimations of sample size and intention‐to‐treat analyses in these two trials. However, the published data of the third trial did not provide any information on the study centre, sample size estimation and statistical analysis (Purificacion 2007). There was also no information on pre‐trial estimation of sample size in the trial of Fuangchan 2011.

Allocation

Only one trial reported both adequate randomisation and allocation concealment (Dans 2007). Although randomisation was adequate in the trial of Fuangchan 2011, there was no allocation concealment as bitter melon and metformin were given as 500 mg capsules and 500 mg tablets, respectively.

Blinding

Double‐blinding procedures were reported in the trials of Dans 2007 and Fuangchan 2011. Such information was lacking in the remaining two trials (John 2003; Purificacion 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

Although there was a withdrawal of a patient in the treatment group in one trial (Dans 2007) and loss to follow‐up of patients in both the treatment and control groups in another (John 2003), there were no indications of the steps taken to address these missing data in the analyses. Furthermore, no time interval was specified for the postprandial blood glucose levels tested (John 2003). This is important because blood glucose level changes with time after a meal. For the remaining trial, information on relevant outcomes was not provided (Purificacion 2007).

Fuangchan 2011 reported an ITT analysis and justifications for withdrawals from the trial. The last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was used to impute missing values. However, LOCF procedures can lead to a serious bias of effect estimates. In addition, there were 6% to 9% of patients withdrawn from the respective intervention arms at various stages, adding to drop‐out bias. Therefore, the data were at unclear risk of incomplete outcome data bias.

Selective reporting

The means and mean differences of primary and secondary outcome measures were provided in the trials of Dans 2007 and Fuangchan 2011 but there were no indications of the range of values for these variables. In the other trial, only means of primary outcomes were provided with no indications of the range of values for these variables (John 2003). There were no details of secondary outcomes reported in the trial of Purificacion 2007.

Other potential sources of bias

There was interest by the sponsor about the efficacy of its products in the trial of Dans 2007, whereas no information was available for the other two trials (Fuangchan 2011; John 2003; Purificacion 2007).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparisons

Different momordica charantia preparations were used in all the four trials (Appendix 2; Appendix 3).

The comparisons were as follows:

momordica charantia capsules (6 capsules) daily versus placebo (Dans 2007);

momordica charantia tablets (three intervention arms with three different doses) daily versus one standard dose of metformin tablets (Fuangchan 2011);

momordica charantia capsules (6 g/day) daily versus placebo (John 2003);

momordica charantia tablets versus glibenclamide tablets (Purificacion 2007).

A meta‐analysis was not performed in view of the quality of the data and the variability of the treatments (no similar momordica charantia preparation was tested twice). The important outcomes from the trials are summarised in Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

Momordica charantia versus placebo

Dans 2007 reported outcomes including fasting blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), total cholesterol, body mass index and adverse effects. Compared with placebo, the fruit and seed capsule preparation showed no statistically significant effect on reduction of fasting blood glucose (Analysis 1.2). Similarly when compared with placebo, the treatment showed no statistically significant reduction in HbA1c levels (Analysis 1.1). For the secondary outcome measures, the treatment showed no statistically significant reduction in total cholesterol levels (Analysis 1.3) or body mass index (Analysis 1.4) when compared to placebo.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Momordica charantia capsules versus placebo, Outcome 2 Change in fasting blood glucose.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Momordica charantia capsules versus placebo, Outcome 1 Change in HbA1c.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Momordica charantia capsules versus placebo, Outcome 3 Change in total cholesterol.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Momordica charantia capsules versus placebo, Outcome 4 Change in body mass index.

The outcomes reported by John 2003 included fasting blood glucose, postprandial blood glucose and fructosamine. Compared with placebo (riboflavin), the shade‐dried powdered fresh whole fruit tablet preparation showed no statistically significant effect on reduction of fasting blood glucose (Analysis 2.1). Similarly, when compared with placebo the treatment showed no statistically significant reduction in postprandial glucose levels (Analysis 2.2). For serum fructosamine, the treatment also showed no statistically significant reduction (Analysis 2.3).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Momordica charantia (dried fruits) tablets versus placebo, Outcome 1 Fasting blood glucose.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Momordica charantia (dried fruits) tablets versus placebo, Outcome 2 Post‐prandial blood glucose.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Momordica charantia (dried fruits) tablets versus placebo, Outcome 3 Change in serum fructosamine.

Momordica charantia versus glibenclamide

The published data of Purificacion 2007 included outcomes of fasting blood glucose, HbA1c and clinical parameters of polyuria, polyphagia, polydipsia, weight loss and nocturia. The authors could not be contacted to provide the raw data for statistical analyses. Nevertheless, from the information provided by the circular, the momordica charantia leaf tablet preparation showed statistically significant effects on reduction of fasting blood glucose. Likewise, there was a statistically significant reduction in HbA1c. The changes in these two parameters were comparable with the control intervention of low dose glibenclamide tablets (2.5 mg twice a day). There was also a comparable improvement of the clinical symptoms of polyuria, polyphagia, polydipsia, weight loss and nocturia.

Momordica charantia versus metformin

The outcomes reported by Fuangchan 2011 included fasting blood glucose, 2‐hour postprandial blood glucose and fructosamine. A significant reduction in mean fructosamine levels from baseline was found only in patients who received metformin 1000 mg/day (‐16.8 μmol/L; 95% CI ‐31.2 to ‐2.4 μmol/L, 129 participants, 1 trial, P < 0.05) and bitter melon 2000 mg/day (‐10.2 μmol/L; 95% CI ‐19.1 to ‐1.3 μmol/L, 129 participants, 1 trial, P < 0.05). However, the mean change of fructosamine levels from baseline was not significantly different between treatments (P = 0.43) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Momordica charantia (dried fruits) capsules versus metformin, Outcome 1 Serum fructosamine.

Adverse events

Adverse events are summarised in Appendix 5. No serious adverse events were reported in three of the trials (Dans 2007; Fuangchan 2011; Purificacion 2007) and no adverse effects were documented in the remaining trial (John 2003). In the trial of Dans 2007, one patient dropped out of the study after one month with diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Two other patients also had diarrhoea two months into the trial. Another was admitted for gastroenteritis. The latter three patients resumed taking medications when their symptoms were resolved. Fever, urinary incontinence, chest pain and cholecystolithiasis were also reported in the treatment group. The last symptom, however, was not reported to be causally related to the treatment. Comparable mild adverse effects of nausea, gastric pain, headaches and dizziness were noted in both the treatment and control groups in the report of Purificacion 2007. There was no clinical meaningful difference in overall adverse events reported as well as no serious adverse events in Fuangchan 2011. Only mild adverse effects on the various systems were documented. These symptoms did not require any treatment, discontinuation of metformin or bitter melon and resolved with rest.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to assess the effects of momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Summary of main results

The trials included in this review measured surrogate outcomes and evaluated adverse events (Appendix 5). Compared with the placebo, the momordica charantia capsules and tablets did not show any significant improvement of blood glucose control in terms of normalisation or a reduction of fasting blood glucose, reduction of glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or fructosamine (Dans 2007; John 2003). Only momordica charantia capsules in doses of 2000 mg/day, in the trial of Fuangchan 2011, demonstrated statistically significant improvement in fasting blood glucose as well as 2 hour postprandial blood glucose. There was no improvement noted in the secondary outcome measures of total cholesterol and body mass index (BMI) in the trial of Dans 2007. However, one should be cautious in interpreting the findings due to the low methodological quality and the generally small sample size in these trials contributing to the low power of the studies. Although the published data of Purificacion 2007 reported that the effect of the momordica charantia leaf preparation intervention was comparable with the control intervention of low dose glibenclamide tablets (2.5 mg twice a day), there was insufficient information for assessing the risk of bias in this study. In all these four studies, there were no statements on the health‐related quality of life, adverse effects or costs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only four trials were selected for the review. All the trials used preparations from different parts of the momordica charantia plant in the interventions. Moreover, the interventions in the control groups of the three trials also varied. Two used placebos (Dans 2007; John 2003) whereas the others used glibenclamide tablets (Purificacion 2007) and metformin tablets (Fuangchan 2011). In addition, the time point for assessment of the effect of the intervention was not uniform for the four trials. This time point was four weeks for the trials of John 2003 as well as Fuangchan 2011 and three months for the other two trials (Dans 2007; Purificacion 2007).

Quality of the evidence

All the trials were assessed as having high risk of bias since they did not meet one or more essential risk of bias criteria. No trial was assessed as at moderate or low risk of bias. Low risk of bias is indicated when quality criteria in terms of minimisation of selection, performance, attrition and detection biases are met. Categorization into moderate risk of bias required the quality criteria to be partially fulfilled.

Potential biases in the review process

This systematic review has several limitations. First, there are limited trials available for selection. This may be due to publication bias. Further, all the included trials suffer from methodological issues. Poor quality of randomisation and blinding may be associated with exaggerated effects of the intervention due to systematic errors (bias). This potential bias may occur during selection of patients, administration of treatment, and assessment of outcomes. Moreover, methodologically less rigorous trials have shown significantly larger intervention effects than trials with more rigour (Egger 2003; Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995). Second, the small sample size of the trials leading to diminished power of the results may explain the absence of a statistically significant difference between the preparation of momordica charantia used for the intervention and placebo. In other words, the analyses from trials of this size may not establish with confidence that two interventions have equivalent effects (Piaggio 2001; Pocock 1991). Third, all trials reported end‐of treatment responses, ranging from four weeks to three months, and long‐term responses beyond this period are not known. Fourth, all the preparations used in the intervention arms were tested only once, which made it impossible to pool data. Finally, although all the trials did not provide information on ethnicity of the participants, the recruitment of patients was limited to the respective centre of study in two trials and no information was available in the remaining two trials. Thus, the validity and applicability of the results to other ethnic groups or populations is not known.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Previous reviews focused on experimental studies of animal and clinical trials in humans. No RCT was included. However, in this review the four RCTs selected showed variability of the treatment interventions, control interventions and had generally small effect sizes. Moreover, none of the preparations were tested twice. This unfortunately does not provide sufficient evidence for any reliable conclusions on the potential benefits or harmful effects of momordica charantia for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus or prevention of complications of the disease.

Implications for research.

Although there is reasonable evidence from animal models, few human studies, and an RCT suggesting that momordica charantia may help in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a potential methodological problem is the quality of the preparation of momordica charantia. The conditions for growing, harvesting and processing the plant, as well as climatic variations, are sources of differences and contaminations (WHO 2007). In addition, the use of different parts of the plant further adds to the complexity involved in characterisation as well as the production of reliable and consistently effective products. Thus, there is a need for further studies to address the standardization and the quality of the products used in clinical trials.

Research into the effects of momordica charantia on the independent protective effect for long‐term complications in humans is still unavailable. The presence of confounders, the variations in the diet as well as the difficulty in recording dietary intake over a long period make it difficult to interpret these confounders when present. How to adequately blind participants in nutritional studies, given the plant’s characteristic bittersweet taste, is another potential methodological problem. Such a taste may be acceptable in communities with a high intake of momordica charantia but may be unacceptable where this plant is less popular. Taste might be 'controlled' through special preparations in the form of capsules and tablets.

However, for the older adults with T2DM, nutritional goals focused on counting calories in glycaemic control rather than promoting healthy, balanced food intake has been found to be detrimental to health (Payette 2005). Adding to the combination of body composition as well as physiological changes with the aging process, pathology, polypharmacy and psycho‐social factors (for example depression) greatly accelerate the negative trajectory of aging leading to increased falls, fractures and consequent disabilities (Alibhai 2005; Payette 1998; Payette 2005). Thus, further observational trials to evaluate the effects of momordica charantia on T2DM in medical nutritional therapy are justified, particularly in parts of the world where the use of this vegetable is common. For reliable conclusions any such trials should be large and of rigorous quality.

Feedback

New feedback, 27 October 2013

Summary

Comment to the Editor: The main results section of the abstract said "There was no statistically significant difference in the glycaemic control with momordica charantia preparations compared to placebo. When momordica charantia was compared to metformin or glibenclamide, there was also no significant change in reliable parameters of glycaemic control." Metformin and glibenclamide are definitely significantly different from the placebo. This fact is not compatible with both the above statements being correct at the same time. It was not clear to me why the more accurate and not confusing statements in the previous version were updated to this version.

Reply

The statement in the results section of the abstract is correct and highlights the fact that some RCTs (all with limited amount of data investigating surrogate outcomes only) compared momordica charantia with placebo and other trials compared momordica charantia to metformin or glibenclamide (again all with limited amount of data investigating surrogate outcomes only) demonstrating no statistically significant differences between intervention and comparator groups. This does not imply that metformin or glibenclamide are not different to placebo which would be an unjustified indirect comparison. The main message of this review however is that data on patient‐important outcome measures are missing.

Contributors

Annotator: Jih‐I Yeh.Department of Family Medicine, Buddhist Tzu‐Chi General Hospital and Tzu‐Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan (jihiyeh@gms.tcu.edu.tw).

Responder: Bernd Richter, Coordinating Editor Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 November 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | New feedback incorporated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2009 Review first published: Issue 2, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 May 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No change in the results and conclusions of the review. |

| 22 May 2012 | New search has been performed | One additional study (Fuangchan 2011) was included. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Karla Bergerhoff (Trials Search Coordinator) for her kind advice and support during the review process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Search terms and databases |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms; MeSH = Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); exp = exploded MeSH; the dollar sign ($) or asterisk (*) stand for any character(s); the question mark (?) = to substitute for one or no characters; ab = abstract; adj = adjacent; ot = original title; pt = publication type; rn = Registry number or Enzyme Commission number; sh = MeSH; ti = title; tw = text word. |

| The Cochrane Library |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Diabetes mellitus, type 2 explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Insulin resistance explode all trees #3 ( (impaired in All Text and glucose in All Text and toleranc* in All Text) or (glucose in All Text and intoleranc* in All Text) or (insulin* in All Text and resistanc* in All Text) ) #4 (obes* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #5 (MODY in All Text or NIDDM in All Text or TDM2 in All Text) #6 ( (non in All Text and insulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (noninsulin* in All Text and depend* in All Text) or (non in All Text and insulindepend* in All Text) or noninsulindepend* in All Text) #7 (typ* in All Text and (2 in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #8 (typ* in All Text and (II in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #9 (non in All Text and (keto* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #10 (nonketo* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #11 (adult* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #12 (matur* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #13 (late in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #14 (slow in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #15 (stabl* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) #16 (insulin* in All Text and (defic* in All Text near/6 diabet* in All Text) ) #17 (plurimetabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #18 (pluri in All Text and metabolic in All Text and syndrom* in All Text) #19 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10) #20 (#11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18) #21 (#19 or #20) #22 MeSH descriptor Diabetes insipidus explode all trees #23 (diabet* in All Text and insipidus in All Text) #24 (#22 or #23) #25 (#21 and not #24) #26 MeSH descriptor Momordica charantia explode all trees #27 MeSH descriptor Cucurbitaceae explode all trees #28 cucurbitaceae in All Text #29 ( (bitter in All Text and melon in All Text) or (bitter in All Text and gourd in All Text) #30 (momordica in All Text and charantia in All Text) #31 (#26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30) #32 (#25 and #31) |

| MEDLINE |

| 1. momordica charantia.mp. 2. bitter melon.mp. 3. bitter gourd.mp. 4. cucurbitaceae.mp. 5. or/1‐4 6. exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/ 7. exp Insulin Resistance/ 8. exp Glucose Intolerance/ 9. (impaired glucos$ toleranc$ or glucos$ intoleranc$ or insulin resistan$).tw,ot. 10. (obes$ adj3 diabet$).tw,ot. 11. (MODY or NIDDM or T2DM).tw,ot. 12. (non insulin$ depend$ or noninsulin$ depend$ or noninsulin?depend$ or non insulin?depend$).tw,ot. 13. ((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?2 or typ?II) adj3 diabet$).tw,ot. 14. ((keto?resist$ or non?keto$) adj6 diabet$).tw,ot. 15. (((late or adult$ or matur$ or slow or stabl$) adj3 onset) and diabet$).tw,ot. 16. or/6‐15 17. exp Diabetes Insipidus/ 18. diabet$ insipidus.tw,ot. 19. 17 or 18 20. 16 not 19 21. 5 and 20 22. randomized controlled trial.pt. 23. controlled clinical trial.pt. 24. randomi?ed.ab. 25. placebo.ab. 26. drug therapy.fs. 27. randomly.ab. 28. trial.ab. 29. groups.ab. 30. or/22‐29 31. Meta‐analysis.pt. 32. exp Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ 33. exp Meta‐analysis/ 34. exp Meta‐analysis as topic/ 35. hta.tw,ot. 36. (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 37. (meta analy$ or metaanaly$ or meta?analy$).tw,ot. 38. ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systemat$)).tw,ot. 39. or/31‐38 40. (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 41. 39 not 40 42. 30 or 41 43. 21 and 42 44. (animals not (animals and humans)).sh. 45. 43 not 44 |

| EMBASE |

| 1. exp Momordica charantia extract/ or exp Momordica charantia/ 2. bitter lemon.tw,ot. 3. bitter gourd.tw,ot. 4. cucurbitaceae.tw,ot. 5. momordica charantia.tw,ot. 6. or/1‐5 7. exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/ 8. exp Insulin Resistance/ 9. (MODY or NIDDM or T2D or T2DM).tw,ot. 10. ((typ? 2 or typ? II or typ?II or typ?2) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 11. (obes* adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 12. (non insulin* depend* or non insulin?depend* or noninsulin* depend* or noninsulin?depend*).tw,ot. 13. ((keto?resist* or non?keto*) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 14. ((adult* or matur* or late or slow or stabl*) adj3 diabet*).tw,ot. 15. (insulin* defic* adj3 relativ*).tw,ot. 16. insulin* resistanc*.tw,ot. 17. or/7‐16 18. exp Diabetes Insipidus/ 19. diabet* insipidus.tw,ot. 20. 18 or 19 21. 17 not 20 22. 6 and 21 23. exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 24. exp Controlled Clinical Trial/ 25. exp Clinical Trial/ 26. exp Comparative Study/ 27. exp Drug comparison/ 28. exp Randomization/ 29. exp Crossover procedure/ 30. exp Double blind procedure/ 31. exp Single blind procedure/ 32. exp Placebo/ 33. exp Prospective Study/ 34. ((clinical or control$ or comparativ$ or placebo$ or prospectiv$ or randomi?ed) adj3 (trial$ or stud$)).ab,ti. 35. (random$ adj6 (allocat$ or assign$ or basis or order$)).ab,ti. 36. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj6 (blind$ or mask$)).ab,ti. 37. (cross over or crossover).ab,ti. 38. or/23‐37 39. exp meta analysis/ 40. (metaanaly$ or meta analy$ or meta?analy$).ab,ti,ot. 41. ((review$ or search$) adj10 (literature$ or medical database$ or medline or pubmed or embase or cochrane or cinahl or psycinfo or psyclit or healthstar or biosis or current content$ or systematic$)).ab,ti,ot. 42. exp Literature/ 43. exp Biomedical Technology Assessment/ 44. hta.tw,ot. 45. (health technology adj6 assessment$).tw,ot. 46. or/39‐45 47. (comment or editorial or historical‐article).pt. 48. 46 not 47 49. 38 or 48 50. 22 and 49 51. limit 50 to human |

| Proquest Health and Medical Complete |

| ("mo???dica charantia") OR ("bitter melon") OR ("bitter gourd") OR ("cucurbitaceae") Citation and document text ("clinical trial*") OR (random*) OR (control*) OR (blind*) Citation and document text (("mo???dica charantia") OR ("bitter melon") OR ("bitter gourd") OR ("cucurbitaceae")) AND (("clinical trial*") OR (random*) OR (control*) OR (blind*)) Citation and document text ("meta‐analysis") OR (review*) AND NOT (letter*) AND NOT (comment*) AND NOT (editor*) Citation and document text (("mo???dica charantia") OR ("bitter melon") OR ("bitter gourd") OR ("cucurbitaceae")) AND (("meta‐analysis") OR (review*) AND NOT (letter*) AND NOT (comment*) AND NOT (editor*)) Citation and document text (HTA) OR ("health technology W/6 assess*") OR ("biomedical W/6 technology assess*") Citation and document text ("typ* 2") OR ("typ* II") OR ("late") OR ("maturity") OR ("n???insulin") AND ("diabet*") Citation and document text (NIDDM*) OR (MODY*) OR (TIIDM) OR (T2DM) Citation and document text (("typ* 2") OR ("typ* II") OR ("late") OR ("maturity") OR ("n???insulin") AND ("diabet*")) OR ((NIDDM*) OR (MODY*) OR (TIIDM) OR (T2DM)) Citation and document text ((("typ* 2") OR ("typ* II") OR ("late") OR ("maturity") OR ("n???insulin") AND ("diabet*")) OR ((NIDDM*) OR (MODY*) OR (TIIDM) OR (T2DM))) AND ((("mo???dica charantia") OR ("bitter melon") OR ("bitter gourd") OR ("cucurbitaceae")) AND (("clinical trial*") OR (random*) OR (control*) OR (blind*))) Citation and document text ((("typ* 2") OR ("typ* II") OR ("late") OR ("maturity") OR ("n???insulin") AND ("diabet*")) OR ((NIDDM*) OR (MODY*) OR (TIIDM) OR (T2DM))) AND ((("mo???dica charantia") OR ("bitter melon") OR ("bitter gourd") OR ("cucurbitaceae")) AND (("meta‐analysis") OR (review*) AND NOT (letter*) AND NOT (comment*) AND NOT (editor*))) Citation and document text ((("typ* 2") OR ("typ* II") OR ("late") OR ("maturity") OR ("n???insulin") AND ("diabet*")) AND ((NIDDM*) OR (MODY*) OR (TIIDM) OR (T2DM))) AND ((HTA) OR ("health technology W/6 assess*") OR ("biomedical W/6 technology assess*"))) Citation and document text |

Appendix 2. Baseline characteristics (I)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) & control(s) | Duration of intervention | Duration of follow‐up | Participating population | Country | Setting | Ethnic groups [%] | Duration of disease [mean years (SD)/range] |

| Dans 2007 | momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 3 months | 3 months | adults | The Phillipines | out‐patients | ‐ | ‐ |

| placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | ||||||||

| Fuangchan 2011 | momordica charantia 500 mg/day momordica charantia 1000 mg/day momordica charantia 2000 mg/day |

4 weeks | 4 weeks | adults | Thailand | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| metformin | ||||||||

| John 2003 | momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 4 weeks | 4 weeks | adults | India | out‐patients | ‐ | ‐ |

| placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | ||||||||

| Purificacion 2007 | momordica charantia | 12 weeks | ‐ | adults | The Phillipines | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| glibenclamide | ||||||||

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation | ||||||||

Appendix 3. Baseline characteristics (II)

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Intervention(s) & control(s) | Sex [%female] | Age [mean (SD)/range] | HbA1c [mean (SD)/range] | Co‐medications / Co‐interventions | Co‐morbidities |

| Dans 2007 | momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 65 | 58.7 (9.8) | 7.9 (0.6) | oral hypoglycaemic agents | ‐ |

| placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 60 | C: 59.8 (10.0) | C: 8.1 (0.8) | |||

| all: | 63 | 59.2 (12.3) | ‐ | |||

| Fuangchan 2011 | momordica charantia 500 mg/day momordica charantia 1000 mg/day momordica charantia 2000 mg/day |

76 81. 65 |

52.2 (8.3) 50.6 (10.7) 52.0 (9.1) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| metformin | 73 | 52.5 (9.2) | ‐ | |||

| all: | 74 | 51.8 (9.3) | ‐ | |||

| John 2003 | momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 73 | ‐ | ‐ | oral hypoglycaemic agents | ‐ |

| placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | 63 | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| all: | 68 | 52.8 (7.9) | ‐ | |||

| Purificacion 2007 | momordica charantia | 59 | ‐ | 12.3 (2.1) | ‐ | ‐ |

| glibenclamide | 58 | 12.2 (2.2) | ||||

| all: | 59 | ‐ | ||||

|

Footnotes "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

Appendix 4. Matrix of study endpoints

|

Characteristic Study ID |

Primary1 endpoint(s) | Secondary2 endpoint(s) | Other3 endpoint(s) |

| Dans 2007 | change in HbA1c after treatment | change in fasting blood glucose, serum cholesterol and weight | change in serum creatinine, AST, ALT, sodium, potassium incidence of adverse events |

| Fuangchan 2011 | fructosamine | fasting plasma glucose and 2h plasma glucose after a 75‐g glucose load | safety was monitored by assessing patient reported symptoms, changes in findings on physical examination, vital signs, laboratory tests (complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and liver function test), and reports of hypoglycemia |

| John 2003 | change in serum fructosamine level after treatment FBG PPG | ‐ | ‐ |

| Purificacion 2007 | change in HbA1c level after treatment FBG | clinical parameters of polyuria, polyphagia, polydipsia, weight loss and nocturia | ‐ |

|

Footnotes 1,2 verbatim statement in the publication; 3 not explicitly stated as primary or secondary endpoint(s) in the publication "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: ALT: alanine aminotransferase ; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; C: control; FBG: fasting blood glucose; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; I: intervention; PPG: post‐prandial glucose | |||

Appendix 5. Adverse events

|

Study ID Characteristic |

Dans 2007 | Fuangchan 2011 | John 2003 | Purificacion 2007 |

| Intervention | momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | momordica charantia 500 mg/day momordica charantia 1000 mg/day momordica charantia 2000 mg/day |

momordica charantia + oral hypoglycaemic agents | momordica charantia |

| Control | placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | metformin | placebo + oral hypoglycaemic agents | glibenclamide |

| Deaths [n] | I1: 0/20 C: 0/20 T: 0/40 |

I1: 0/33 I2: 0/32 I3: 0/31 C: 0/33 T: 0/129 |

I: 0/26 C: 0/24 T: 0/50 |

I: 0/128 C: 0/132 T: 0/260 |

| Adverse events [n (%)] | I: 7/20 (35) C: 1/20 (5) T: 8/40 (20) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Serious adverse events [n (0%)] | I: 0/20 (0) C: 0/20 (0) T: 0/40 (0) |

I1: 0/33 (0) I2: 0/32 (0) I3: 0/31 (0) C: 0/33 (0) T: 0/129 (0) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Drop‐outs due to adverse events [n (%)] | I: 1/20 (5) C: 0/20 (0) T: 1/40 (2.5) |

I1: 0/33 (0) I2: 0/32 (0) I3: 0/31 (0) C: 0/33 (0) T: 0/129 (0) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Hospitalisation [n (%)] | I: 2/20 (10) C: 0/20 (0) T: 2/40 (5) |

I1: 0/33 (0) I2: 0/32 (0) I3: 0/31 (0) C: 0/33 (0) T: 0/129 (0) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Out‐patient treatment [n (%)] | I: 6/20 (30) C: 1/20 (5) T: 7/40 (17.5) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hypoglycaemic episodes [n (%)] | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Other symptoms [n (%)] | I: 7/20 (35) C: 1/20 (5) T: 8/40 (20) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Footnotes: "‐" denotes not reported Abbreviations: C: control; I: intervention; T: total | ||||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Momordica charantia capsules versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in HbA1c | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Change in fasting blood glucose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Change in total cholesterol | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Change in body mass index | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 2. Momordica charantia (dried fruits) tablets versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fasting blood glucose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Post‐prandial blood glucose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Change in serum fructosamine | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 3. Momordica charantia (dried fruits) capsules versus metformin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Serum fructosamine | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 momordica charantia 2000mg/day versus metformin | 1 | 62 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 6.60 [‐9.64, 22.84] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Dans 2007.

| Methods | PARALLEL RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL | |

| Participants |

WHO PARTCIPATED: 40 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus SETTING: Out‐patients' clinic of general hospital in Manilla, The Phillipines SEX (female:male ratio): 5:3 AGE (mean years (SD)): 59.2 (SD 12.3) ETHNIC GROUPS (%): No information DURATION OF DISEASE (mean years (SD)): No information INCLUSION CRITERIA: At least 18 years old; diagnosed by physicians to have type 2 diabetes mellitus; suboptimal glycaemic control EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Evidence of hepatic dysfunction; known allergy to momordica charantia or its products; presence of severe chronic illness; presence of acute illness; presence of illness limiting life expectancy; presence of conditions affecting compliance; recipient of another investigational product during and 3 months preceding and pregnancy or lactation. DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA: Authors' criteria CO‐MORBIDITIES: No information CO‐MEDICATIONS: Oral hypoglycaemic agents but no information on the types of pharmacological agents |

|

| Interventions |

Experimental intervention: Preparations from fruits and seeds of momordica charantia plant were in the form of capsules. Two capsules were given three times daily after meal for a period of three months. Control intervention: Placebo capsules. No information on the contents of these capsules. All patients were on concomitant oral hypoglycaemic agents and diet regimen during the study. |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOME(S) (as stated in the publication): change in HbA1c after treatment SECONDARY OUTCOMES (as stated in the publication): change in fasting blood glucose, serum cholesterol and weight ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES: change in serum creatinine, AST, ALT, sodium, potassium and incidence of adverse events |

|

| Study details |

DURATION OF INTERVENTION: 3 months DURATION OF FOLLOW‐UP: Monthly RUN‐IN PERIOD: No information |

|

| Publication details |

LANGUAGE OF PUBLICATION: English COMMERCIAL FUNDING PUBLICATION STATUS: peer review journal |

|

| Stated aim of study | To determine if addition of momordica charantia capsules to standard therapy can decrease glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level in diabetic patients with poor glucose control. | |

| Notes | The author was contacted but did not reply. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random allocation using a computer‐generated sequence (Stata version 6.0). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Medications were prepared by third party. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The patients, investigators and the statistician were blinded until the end of the analysis. The treatment and placebo capsules matched in appearance and were packaged in unmarked blisters. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Despite one patient dropping out after a month due to adverse effects of treatment, the authors mentioned 'all patients were included in the analysis'. There was no indication of how this missing information was addressed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Only mean differences of primary and secondary outcome measures were provided. There were no indications of the range of values for these variables. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sponsored by company to investigate efficacy of their product. |

Fuangchan 2011.

| Methods | PARALLEL RANDOMISED CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL | |

| Participants |

WHO PARTCIPATED: 143 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus SETTING: Clinics of four hospitals in Thailand. SEX (female:male ratio): ˜ 3:1 AGE (mean years (SD)): 51.8 (SD 9.3) ETHNIC GROUPS (%): No information DURATION OF DISEASE (mean years (SD)): No information INCLUSION CRITERIA: Between 35 and 70 years of age, newly diagnosis with type 2 diabetes based on a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) > 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or 2‐h postprandial glucose levels during 75‐g oral glucose tolerance‐test (OGTT) > 200 mg/dL (11.0 mmol/L) (ADA 2006), and whose FPG levels < 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L). EXCLUSION CRITERIA: serum creatinine higher than 1.8 mg/dL; serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin or alkaline phosphatase higher than 2.5 times of the upper normal range; anaemia (haemoglobin <11 g/dL for male, <10 g/dL for female); severe angina; moderate‐severe heart failure with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH); pregnant and lactating women sulfonylureas, metformin, thiazolidinediones, glinides, alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors or insulin use prior to study enrollment; participation in another clinical trial within 30 days of screening; long‐term diabetic complications such as diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy which need therapy (painful peripheral neuropathy, systemic orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention, foot ulcers or gastric stasis); a body mass index (BMI) less than 18 or greater than 38; or a body weight variation more than 10% during the screening period. DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA: American Diabetes Association criteria (ADA 2006) CO‐MORBIDITIES: Hypertension, dyslipidemia, asthma and thyroid diseases CO‐MEDICATIONS: Medications for co‐morbidities (no information on specific medications) |

|

| Interventions |

Experimental intervention: Preparations from dried unripe fruit pulp of momordica charantia plant were made in the form of capsules. Each capsule contained 500mg of dried powder of the fruit pulp, containing 0.04–0.05% (w/w) of charantin. Three doses were used: 500 mg/day, 1000 mg/day, 2000 mg/day of bitter melon. Control intervention: Metformin tablets of 500 mg each were used. Placebo: The placebo of bitter melon capsules was roasted rice powder while the placebo for metformin table was lactose tablet. All patients were counseled regarding dietary and lifestyle modification. |

|

| Outcomes |

PRIMARY OUTCOME(S) (as stated in the publication): Mean change in fructosamine from baseline to endpoint. SECONDARY OUTCOMES (as stated in the publication): Mean change in fasting plasma glucose and 2‐h plasma glucose after a 75‐g glucose load from baseline to endpoint. ADDITIONAL OUTCOMES: Safety was monitored by assessing patient reported symptoms, changes in findings on physical examination, vital signs, laboratory tests (complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and liver function test), and reports of hypoglycemia. |

|

| Study details |

DURATION OF INTERVENTION: 4 weeks DURATION OF FOLLOW‐UP: week 1 and week 4 RUN‐IN PERIOD: 2 weeks |

|

| Publication details |

LANGUAGE OF PUBLICATION: English NON‐COMMERCIAL FUNDING PUBLICATION STATUS: peer review journal |

|

| Stated aim of study | To assess the efficacy and safety of three doses of bitter melon compared with metformin. | |

| Notes | Original research article. The author was contacted but did not reply. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "eligible patients were randomized to one of the four arms: ....... bitter melon or .......metformin by block randomization". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "Bitter melon and metformin were supplied as 500mg capsules and 500mg tablets, respectively". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: ".......double dummy technique was used". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "Last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was used for missing values". Attempts were made to addressed missing data using the LOCF approach, LOCF procedures can lead to serious bias of effect estimates. About 6% to 9% of the data were subjected to such approach. |