Abstract

Background

This study used a standard research approach to create a final conceptual model and the Preference for the Testosterone Replacement Therapy (P-TRT) instrument.

Methods

A discussion guide was developed from a literature review and expert opinion to direct one-on-one interviews with participants who used testosterone replacement therapy and consented to participate in the study. Data from telephone interviews were transcribed for theme analysis using NVivo 9 qualitative analysis software, analyzed descriptively from a saturation grid, and used to evaluate men’s P-TRT. Data from cognitive debriefing for five participants were used to evaluate the final conceptual model and validate the initial P-TRT instrument.

Results

Item saturation and theme exhaustion was achieved by 58 male participants of mean age 55.0 ± 10.0 (22–69) years who had used testosterone replacement therapy for a mean of 175.0 ± 299.2 days. The conceptual model was developed from items and themes obtained from the participant interviews and saturation grid. Items comprising eight dimensions were used for instrument development, ie, ease of use, effect on libido, product characteristics, physiological impact, psychological impact, side effects, treatment experience, and preference. Results from the testosterone replacement therapy preference evaluation provide a detailed insight into why most men preferred a topical gel product over an injection or patch.

Conclusion

Items and themes relating to use of testosterone replacement therapy were in concordance with the final conceptual model and 29-item P-TRT instrument. The standard research approach used in this study produced the P-TRT instrument, which is suitable for further psychometric development and use in clinical practice.

Keywords: hormones, hypogonadism, outcome assessment, patient preference, testosterone

Introduction

The general prevalence of symptomatic hypogonadism is 6%–12% in the United States.1,2 While prevalence estimates for hypogonadism are higher for elderly men (5.1%) compared with middle-aged men (2.1%) with low serum testosterone (ie, <320 ng/dL, 11 nmol/L),3 data from the Boston Area Community Health Survey suggest that symptoms of hypogonadism may be experienced by up to 4.7 million American men aged 30–79 years.4 Aside from the changes that occur as part of the natural aging process, testosterone levels are influenced by lifestyle (eg, alcohol, caffeine, tobacco), psychological factors (eg, mood, stress), and comorbidities, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and sleep disorders.5 As men experience reductions in testosterone levels, patient-reported outcomes such as quality of life and well-being are also affected.6,7

Because testosterone contributes to the regulation of sexual function, mood, muscle mass, liver function, bone formation, and immune function,8 males who present with low levels of testosterone (eg, <320 ng/dL, 11 nmol/L) are more likely to experience common symptoms associated with hypogonadism.9,10 These symptoms include fatigue, reduced sex drive, lack of energy, mood changes, and regression of secondary sexual characteristics.11 Although decreases in total testosterone levels of 1%–2% per year are frequently associated with the aging process,12 recent evidence suggests that declining testosterone levels can occur independent of age when lifestyle factors are considered.13 Regardless of etiology, men’s efforts to seek medical attention for hypogonadism usually peak when symptoms interfere with lifestyle, relationships, and sexual activity.

Once a diagnosis of hypogonadism is confirmed by assessment of total and free testosterone levels, testosterone replacement therapy is the mainstay of treatment to address the clinical manifestations of hypogonadism.14 Recommendations for testosterone therapy can be initiated with any of the suggested regimens in accordance with considerations of the patient’s preference, pharmacokinetics of the testosterone formulation, treatment burden, and cost.15 However, determining which product is preferred by patients may be challenging, given the number of products currently on the market and the options for route of administration (eg, injection, implant, patch, topical, and oral). Given that physicians consider product characteristics for each delivery system with respect to outcomes desired by patients, optimal patient experience with the product selected is most likely to occur if patient preferences are factored into a physician’s product choice. Hence there is the need to evaluate patient preferences for products, which cannot be accomplished directly because they may be unaware of all the product choices. Thus, an opportunity to examine patient preferences regarding testosterone replacement therapy may improve the interaction between physicians and patients so that physicians can prescribe a product for testosterone replacement therapy that is mutually acceptable.

While patient preference studies extend into several patient-reported outcome areas, including medical care,16 asthma,17 overactive bladder,18 insulin delivery,19 and testosterone replacement therapy comparing testosterone injection with the implant,20 a standard data collection instrument to assess patient preference for testosterone replacement therapy products has not been developed. Thus, more information is needed to understand how preference may be influenced by product characteristics (eg, physical qualities, location of application, and duration of use) associated with product selection. An instrument to evaluate patient preference for testosterone replacement therapy will provide physicians with an assessment tool to optimize adherence with testosterone replacement therapy by aligning patient preferences with product characteristics.21 For this study, we used the principles of grounded theory, a type of qualitative research approach, to create a conceptual model and develop and validate an instrument to assess patient Preference for Testosterone Replacement Therapy (P-TRT).

Materials and methods

Conceptualization

In general, we followed the approach suggested in the US Food and Drug Administration patient-reported outcome guidance document, which describes the development and validation of patient-reported outcome measures that could be used in product labeling, hypothesis testing, and other endpoint studies.22 To begin the process of conceptualization, a systematic literature review of testosterone replacement therapy was conducted in the fall of 2011. Content extracted from the literature and expert opinion was used to develop the initial conceptual framework (ie, a graphic depiction of the relevant measurement concepts and specific domains). The literature search was conducted using the following key words: “testosterone replacement”, “treatment experience”, “patient-reported outcomes”, “topical”, “patch”, “injection”, and “preference”. Database searches of Medline and PubMed yielded 125 articles published between 1999 and 2011. Articles were categorized as testosterone replacement therapy review, preference or patient-reported outcome research, compliance, product comparison, or product attributes. Existing instruments were examined and summarized for their ability to contribute to the conceptualization process in ways consistent with current scientific and regulatory standards as described in the Food and Drug Administration patient-reported outcome guidance.22 Because of the paucity of instruments in the testosterone replacement therapy area, instruments from other areas (eg, dermatology and general hormone replacement therapy) were evaluated in terms of their concept coverage (ie, what they measured), development history, content validity, and psychometric performance.

Qualitative study design

Principles from grounded theory, a qualitative research approach, were used to transform the proposed conceptual framework into the final conceptual model for use in development of a P-TRT instrument. Grounded theory refers to a specific methodology on how to get from systematically collecting data to producing a multivariate conceptual theory.23 The principles of grounded theory have been used successfully in health care research to develop conceptual models and tools to advance our understanding of health behavior and to improve interaction between physicians and patients.24,25 A research design using a grounded theory approach will generate data that are rich in detail, thus providing additional insight into social processes (eg, causes, contexts, contingencies, consequences, covariances, and conditions) to understand the patterns,26 and to propose testable relationships between the dimensions that will be represented by the final conceptual model. In summary, the aspect of data collection in grounded theory serves as the nexus to transform the initial conceptual framework into the final conceptual model, which serves as the foundation (ie, grounded by the observations from data collection) for development of a P-TRT instrument.

Using these principles, data collection, interpretation, and comparison were accomplished in three stages. In stage one, data were openly collected and coded from oneon- one participant interviews. To conduct the interviews, a discussion guide was developed from the literature, expert opinion, and detailed responses from five participants who agreed to participate in recorded interviews lasting approximately 1 hour. One-on-one participant interviews were then conducted using the standard set of questions from the discussion guide. Researchers elicited and recorded responses from participants during interview sessions lasting up to 30 minutes. The discussion guide elicited information from participants in the full sample regarding age, length of time using testosterone replacement therapy product(s), experience with product features, product comparison, and preference. Throughout the interview process, researchers were careful not to bias participant responses by mentioning specific product features or expected outcomes from product use. All information gleaned from the participant interviews was transcribed and analyzed qualitatively, entered into a saturation grid to determine the frequency with which certain words or phrases were mentioned by participants and used to evaluate perceived preference.

The saturation grid provides an opportunity for researchers to examine items and phrases for redundancy, consolidation, and clarity, to ensure that each item or phrase is represented independently on the grid. In the second stage, data were grouped according to themes based on similarities in relationships and patterns within and among the categories identified in the data.26 At this point, items and their respective themes were examined by five experts, including one physician, three researchers with extensive experience in psychometrics, and a nurse practitioner with clinical experience in the area of testosterone replacement therapy. Experts regularly discussed the degree of congruency between the content extracted from the literature and the responses provided from participant interviews. The content and structure of the instrument in relation to the final conceptual model was discussed, as well as item wording, interpretation, and relevance to participants on testosterone replacement therapy.

Once consensus was reached that all possible items and themes were exhausted, the final stage was to develop the P-TRT instrument and conduct indepth interviews as part of the cognitive debriefing process. In addition to providing evidence of content and face validity, both participants and researchers engaged in an interactive process to test the instrument in the designated population. The purpose of cognitive debriefing was for investigators to field test the P-TRT instrument and discuss every word, phrase, and sentence until agreement was reached with participants concerning clarity, interpretation, wording, and completeness. All protocols and guides used in the study were approved by the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Boston, MA.

Sample

Participants were selected from a mailing list containing subjects who agreed to participate in research studies pertaining to testosterone replacement therapy for conditions associated with a deficiency or absence of endogenous testosterone. Enrollment via the online manufacturer-sponsored website was voluntary. Participants were asked to provide basic demographic information, type of insurance coverage, and preferred method of contact (eg, email, direct mail, or telephone). In exchange for their participation, participants had the option to accept coupons toward their next purchase of a testosterone replacement therapy product.

Participant enrollment for the US study started in February 2011 and ended in October 2011. When the preference for testosterone replacement therapy study started in October 2011, the database contained a list of 6627 subjects. Of those listed, 1092 subjects had a valid name, consent date, and telephone number listed in the database. Different geographical areas were well represented throughout the US mainland. To be included in the study, participants had to be male, aged > 18 years, have current or previous experience with a testosterone replacement therapy product, and be able to receive testosterone replacement therapy under the supervision of a physician. To be included in the preference subanalysis, participants had to use a testosterone replacement therapy product for more than 1 month and had to have experience with more than one testosterone replacement therapy product. As a strategy to maximize the exchange of information between academic-based investigators and participants, only those participants who provided telephone numbers were contacted. Informed consent was obtained from each participant as they agreed to participate in the study. Once consent was obtained, participants were deidentified during the interview process and throughout all analyses. Thus, investigators were blinded as to the use of specific products and other attributes by specific participants.

Data analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 17.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The content of the participant interviews was transcribed using N-Vivo 9 qualitative analysis software (QSR International, Cambridge, MA). The transcription process included identification of recurring definitions and themes throughout the text, which produced rich descriptions and theoretical explanations of the concepts under investigation. Participant-mentioned words and phrases were documented until all themes and thematic associations with words and phrases were exhausted. To ensure that saturation occurred, responses from each participant were compared with responses from other participants to verify that all possible word combinations used to describe testosterone replacement therapy and respective themes were exhausted. Items and phrases from the participant interviews, including the preference evaluation, were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (ie, saturation grid; Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and analyzed descriptively to assess item frequencies and to determine which themes prevailed. Data entry, coding, and wording of items and phrases were examined by at least two researchers and double-checked for accuracy by a third investigator. Data from cognitive debriefing of participants by trained male, academic-based researchers using the final version of the instrument were conducted until concordance was achieved with respect to item wording, item interpretation, and relationship to testosterone replacement therapy experience and product preference.

Results

Participant interviews and preference study

A total of 489 participants were contacted by telephone during December 2011. In Table 1, saturation of items and exhaustion of themes was achieved by 58 male participants of average age 55.0 ± 10.0 (range 22–69) years. Participants used testosterone replacement therapy for an average of 175.0 ± 299.2 days, with only four participants mentioning problems with insurance coverage for testosterone replacement therapy products. From the total of 58 participants, there were 24 (41.4%) participants who had used a testosterone replacement therapy product for more than 1 month. These participants also provided a product comparison in their testosterone replacement therapy experience or an evaluation of product preference. The average age of these participants was 55.0 ± 7.8 (range 42–68) years, with testosterone replacement therapy use for an average of 299.8 ± 429.9 days. The data were skewed because two of the participants used testosterone replacement therapy for 4 and 5 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of males using testosterone replacement therapy

| All participants n = 58 |

Preference* n = 24 (41.4%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD (range) | 55 ± 10.0 (22–69) | 55 ± 7.8 (42–68) |

| Days of TRT therapy ± SD | 175.5 ± 299.2 | 299.8 ± 429.9 |

Note:

Participants using TRT > 1 month; experience with more than one product formulation or mode of administration.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; TRT, testosterone replacement therapy.

Eight themes emerged from qualitative analysis of the interview data. The first theme, ease of use, encompassed all topical characteristics associated with testosterone gel products. Participants preferred a product that was convenient to use, easy to apply, easy to handle, with accessible application location, and dried quickly. The second theme captured libido and included both sex drive and the desire for a sexual relationship. The third theme related to weight loss, muscle tone, shape, and exercise, all of which described the physiological impact of testosterone replacement therapy. Fourth, the psychological impact was described by participants as feeling better, having more energy, “feeling like myself again”, and stamina. The fifth theme contained items relating to physical product characteristics (eg, texture, did not stain clothing, not greasy, not sticky, and appearance). During the interview, some participants described the sixth theme in terms of side effects, such as rash, irritation, red blotches, and dry and itchy skin. The seventh theme focused on the treatment experience, which included several items and phrases, including pleasing experiences or outcomes, product worked or helped, expectations were met, and satisfied with product use. The last theme, preference, was described as “preferred this product”.

Saturation grid

The saturation grid contained 45 items and phrases that captured the content of the participant interviews. The number of times each item or phrase was mentioned was recorded directly onto the grid for each participant. The frequencies were totaled and grouped into major themes (Table 2). The most salient items and phrases mentioned by 10% or more of the participants were related to product convenience, energy and stamina, and sex drive.

Table 2.

Response rate (%) of participants for major themes of the saturation grid

| Items* | Responses n = 58, (%) |

|---|---|

| Ease of use | 56.9 |

| Energy level | 39.7 |

| Libido | 34.5 |

| Odorless or only a slight odor | 22.4 |

| Fast or quick drying time | 13.8 |

| Convenience | 12.1 |

| Feel better | 10.3 |

| Muscle tone, shape, fat redistribution | 10.1 |

Note:

Participant mention of the reported items and phrases had to be ≥10%.

Preference evaluation

There were four participants who preferred injections over topical gels, with one participant preferring both the injection and topical gel. In situations where testosterone levels were low or fluctuating, participants perceived that the injections maintained their levels better, lasted longer, or brought them into the correct range more efficiently, especially for participants requiring higher doses of testosterone (Table 3). One of these participants preferred an injection every 2 weeks compared with a product that required daily application, while another participant based his preference on product cost. Two participants preferred the patch. The quick application and not having to wash hands were cited as reasons for patch preference. There were 17 participants who liked or preferred the gel for reasons attributed to convenience, ease of use, not staining clothes, more energy, stamina, and increased libido. However, two participants eventually discontinued product use because of ineffectiveness. Although complaints about the topical gel included burning sensation, itching, rash, a peeled-skin appearance, and drying time, some participants preferred the topical gel over the injection, citing the advantages of not having to go to a physician’s office to receive injections and pain avoidance.

Table 3.

Results for participants using testosterone replacement therapy for more than 1 month and having experience with more than one product

| ID | Age | Days | TRT experience | Comparison | Preferred | Current use | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 90 | Effective: pleased with product; apply by myself; no transportation to doctor’s office. | 2 other products | TG | Yes | Feel better, more energy; convenience |

| 2 | 66 | 120 | Effective; pain to put it on everyday; some burning sensations; wait time to dry. | I | TG | Yes | Energy; worked as well as injections |

| 3 | 50 | 270 | Positive: Both about the same. | Another TG | TG | Yes | More energy; decrease mood swings |

| 4 | 54 | 365 | I used another product where I had to do the injection into the muscle, and the gel is easier because there is no sticking and blood, etc. But the injection more potent; lasts longer. | I | TG | Yes | More sex drive; more energy; but skin looks like it’s peeling at times |

| 5 | 46 | 180 | Yes it is the gel, and I apply topically to the inner thigh and I really can’t really tell if it’s working or not because I am on so many other meds, can’t tell any difference. | TG and oral tablets | Patch | Yes | Patch; quicker; more convenient |

| 6 | 64 | 90 | It worked. | Another TG | TG | Switched to another TG | Increased testosterone |

| 7 | 54 | 365 | Helped as far as my energy level. I don’t know if it has helped with regard to erectile dysfunction, I don’t know which part was mental and physical. | Another TG | TG | Yes | Increased energy; sexual desire; outcomes about the same |

| 8 | 47 | 120 | First I found it very expensive; my insurance didn’t cover it at all. I did find that it worked fine. I almost liked it better than the shot; it gave me a normal feel. The shots really hype you up, puts you almost on a cocaine buzz. | Another TG and I | TG | Discontinued; TG - high cost | More natural |

| 9 | 55 | 365 | I don’t use the gel anymore. I didn’t like having to wash my hands every time. | TG | Patch | Switched to a different product | Slept better; lost weight |

| 10 | 45 | 113 | Not effective: I really was expecting like a boost of energy or some type of extra, sexual stamina/ strength or something. I couldn’t really feel much of anything. | I and TG | TG | Discontinued | No efficacy |

| 11 | 68 | 90 | Not very effective: Ease of use was good, no odor but it didn’t work very well. Experienced a boost for a little bit. | Another TG | TG | Discontinued | No efficacy |

| 12 | 66 | 90 | I didn’t like it at all. I was rather annoyed with working with it. Well I didn’t like the time that it take to dry. And then I was running into rash and problems with itching. Never saw results with topical gel. | Two different TGs | I | Switched to injection | Less frequency with injections |

| 13 | 61 | 42 | I put it on. I’m not sure what you want? Don’t know of any side effects. Personally I think that it’s sub therapeutic the dose they have me on. I haven’t used it long enough to get a testosterone level. | TG | I | Yes | Injection: lower cost |

| 14 | 42 | 90 | Overall I guess it would be a fair experience. Well as opposed to injections and other products I’ve used, I guess the gel’s downfall is that you had to wait for it to dry. It wasn’t a noticeable boost, the boost was more gradual. | TG | I | Yes | Injection: better outcomes |

| 15 | 57 | 365 | It’s a product that I plan on continue to use. I will be at the doctor’s office in 3 months in March. The last time I had a testosterone level check my levels were at almost a thousand. So I was very pleased with that. | I | TG | Yes | No pain; ease of use |

| 16 | 62 | 1460 | Very good. It gives you the energy you need. | Another TG | TG | Yes | Okay with all of them |

| 17 | 48 | 1825 | Efficacy: Mixed – the gel works and sometimes it doesn’t. My testosterone level has fluctuated, I had had better results with injecting myself, but it is a painful and longer process. Patch leaves giant red marks; topical gel was less robust than injection. | Injection and patch | TG | Yes | Ease of use; more energy; weight loss |

| 18 | 59 | 270 | Well it works very well, it seems to do very well, I have had it tested for my levels and it seems to work well. | Another product | TG | Yes | Improved stamina, energy, and sex drive; no odor |

| 19 | 45 | 180 | Overall, it’s decent, it irritates the skin but other than that it works well. | 2 other products | TG | Yes | Best one so far |

| 20 | 59 | 180 | Good, but it's not where I wanted it. Supposed to help with erectile dysfunction but it didn’t really help. | Injection | TG | Plans to go back to topical gel | More energy; felt better, but did not appear to help erectile dysfunction |

| 21 | 57 | 45 | I found that it did not reliably keep my testosterone levels up. It just didn’t have the same effect as the other gel. I wasn’t getting the results for sexual drive and energy. | Another TG | TG | Yes | Smooth texture, odorless, clear, quick absorption, no stain |

| 22 | 46 | 90 | It was fine for small doses, 2 squirts per leg. But then my doctor prescribed me to shots because 6 squirts got to be a lot to rub in. | Another TG | I | Switched to injection | Inconvenience; needed a larger dose |

| 23 | 61 | 210 | Well, as compared to the other one it applies much better. It doesn’t leave the same kind of sticky or uncomfortable feeling as the other one does. The overall effect from using it seems to be satisfactory. | Another TG | TG | Yes | Increased energy; sex drive; no negative effects |

| 24 | 59 | 180 | I started taking it because I always seemed tired all the time, when you lose testosterone you lose your sex drive, and it has improved a little. | Both I and TG | Both | Yes | Increased sex drive and energy |

Abbreviations: I, injection; TG, topical gel; TRT, testosterone replacement therapy.

Data from the participant interviews, saturation grid, and preference evaluation were used to modify the proposed conceptual framework. At this stage, the conceptual framework was examined to ensure that a possible alignment existed between each item and dimension in the framework. Once a match was confirmed between items and dimensions, the items were used to develop the initial 31-item P-TRT instrument, and the eight dimensions were arranged to form the final conceptual model. Cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted to evaluate the final conceptual framework, which provided a foundation to validate the initial P-TRT.

Cognitive debriefing interviews

For the cognitive debriefing interviews, 80 further participants were contacted to obtain five participants who agreed to participate in comprehensive interviews using the P-TRT instrument. These five participants with experience of testosterone replacement therapy were instructed to think about testosterone replacement therapy and how each item or phrase in the instrument would influence their decision to use testosterone replacement therapy products. Next, participants were asked to interpret each item in the instrument (eg, item meaning, clarity, and relevance to testosterone replacement therapy) to determine the extent of congruency between participant-provided information and content gleaned from the literature and expert opinion. Participants were encouraged to think aloud, provide definitions for certain items, and discuss the rationale for selecting their responses. In addition, participants were encouraged to ask questions about any of the items mentioned or discussed during the interviews.

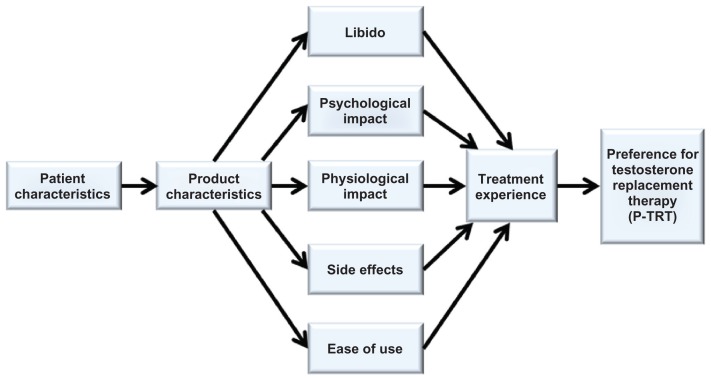

Once cognitive debriefing was completed, researchers reviewed the responses and modified the instrument to improve the wording, clarity, and interpretation. Two items (ie, ease of use and effectiveness) were considered redundant and removed, thus reducing the final P-TRT instrument to 29 items (Appendix) and confirming the themes in the final conceptual model (Figure 1). In the final conceptual model, participant and product characteristics are hypothesized to predict libido, psychological and physiological effects, side effects, and ease of use, which influences the treatment experience and product preference. To ensure that participants could make the connection between testosterone levels (primary patient-reported outcome endpoint measure) and perceived outcomes such as preference, participants were asked to recall what their testosterone levels were at the end of the interview. While only two participants were able to recall their testosterone levels, the other three participants understood the importance of testosterone monitoring and stated it would be easy to obtain this information from their physicians.

Figure 1.

Final conceptual model for testosterone replacement therapy product preference.

Discussion

This study described the creation of a conceptual model and a P-TRT instrument that was developed from consistent and valid responses to assess product preference in participants with hypogonadism. Using a qualitative research approach and principles from grounded theory, data extracted from the literature and expert opinion were used to develop the initial conceptual framework, which was tested and modified throughout the data collection process until the final conceptual model emerged prior to cognitive debriefing. Rich data were obtained from one-on-one interviews with participants, theme analysis, and preference evaluation. Common words, phrases, and themes gleaned from the interviews and theme analysis were supported in the evaluation of preference regardless of how long testosterone replacement therapy was used by participants. The P-TRT instrument, developed in conjunction with the final conceptual model, was validated from the rich data sources and cognitive debriefing.

The P-TRT is the first instrument to offer detailed information provided by participants regarding testosterone replacement therapy preference with respect to several dimensions, including ease of use, libido, product characteristics, physiological impact, psychological impact, side effects, and experience of treatment. In another study investigating how physicians decided to recommend a new medicine for either depression or hypertension, three themes, ie, physician-patient relationship, outside influences (eg, cost, sales representative), and professional expertise, were identified to be related to patient beliefs and preferences.27 As perceived by these patients, physicians were recognized as having the knowledge to recommend specific products that were the best in a given situation.27 Therefore, it would be expected that information gleaned from the P-TRT could be used by physicians to gain knowledge as to how higher-level personal needs (ie, sex drive and desire, and feeling better) relate to patient preference. The rationale is that physician selection and prescribing of products preferred by patients may be viewed more favorably by them and more likely to meet their expectations,28 thus improving their adherence29 and the treatment experience.

In addition to development of the P-TRT, another contribution of this study was the creation of a conceptual model for use in future research. Whereas the initial conceptual framework specifies a broad taxonomy of patient-focused outcomes relevant to a given disease or health condition, the final conceptual model goes one step further by proposing causal linkages and relationships between these outcomes.30 Cognitive debriefing reinforces the entire process of conceptualization and instrument development by engaging both researchers and participants in discussions that confirm all aspects of data collection. A careful examination of data collected at each juncture ensures that the final conceptual model is operational in that data collection will lead to hypothesis testing, theory development, and advances in the understanding of testosterone replacement therapy product preference. Thus, the conceptual framework can serve as a starting point to monitor how physician-based testosterone replacement therapy product recommendations influence patient preferences across multiple scenarios (eg, first time versus experienced testosterone replacement therapy use).

The limitations of qualitative studies primarily focus on sampling procedures and to some extent data collection. While the number of participants included in the study was sufficient to meet the study objectives, it is possible that bias was introduced by limiting contact to participants with active telephone numbers. In addition, the sample was purposive and provided convenient access to participants. Thus, some individuals not contacted may have different perceptions of product preference that were not measured. The one-on-one interview format conducted by trained, male researchers from an academic setting was selected to optimize the exchange of information between participants and researchers. Our thinking was that participants would feel more comfortable discussing issues related to testosterone replacement therapy using a more personal and private format. However, different circumstances (eg, focus groups, email), could produce different results.

In this study, insurance issues were cited by four participants. One of these participants was on a co-pay assistance program and had to pay the difference in cost to use the preferred topical gel. Another had to switch because insurance coverage eventually ended after he became unemployed. The other two participants had to switch from either a topical gel to another topical gel or injection because of cost. Although insurance-related issues were limited to these four participants, preference may be influenced by other variables, such as insurance benefit design and relative product costs in tiered co-pay programs. Hence, a potential selection bias may exist because preference could be driven by insurance-related issues. Additional research is needed to understand the impact of various cost and access issues on product preference.

To participate in the evaluation of preference, participants had to have prior experience of at least one other testosterone replacement therapy product. Although a control group was not considered, nine participants who had used testosterone replacement therapy for less than 1 month had similar expectations regarding sex drive, energy, and benefits from product ease of use (eg, dries quickly, no staining, and not sticky). However, as with the use of any medication, perceptions of preference may change as participants evaluate other products having different formulations or routes of administration. Given the controlled distribution of products for testosterone replacement therapy and the important role that physicians play in recommending testosterone replacement therapy, future studies are needed to extend development of the instrument so the results can be applied in clinical practice. In addition to further assessment of reliability, validity, and items to test the relative importance of relationships among the dimensions that are hypothesized to exist in the final conceptual model, the instrument should be evaluated under different experimental conditions. Although gels and long-acting injectable formulations represent the most modern preparations that can satisfy the criteria for chronic replacement therapy,31 most participants in this study were experienced in the use of topical products based on the study selection criteria and previous experience. Nonetheless, some patients selected topical gels over injections for reasons (eg, transportation issues, having to go to the physician’s office) not related to product features. Thus, future studies are needed to examine how product preference and adherence to physician’s recommendations may be influenced by external factors or how product preferences may contribute to more effective therapy in those situations. Further, more research is needed to understand the role of injectable testosterone replacement therapy products in patient preference and adherence.

Conclusion

In this study, principles from grounded theory were used to transform the proposed conceptual framework into the final conceptual model. Items comprising the dimensions in this model were then used to develop the P-TRT instrument to assess product preference among participants with symptoms of hypogonadism. The instrument was developed using a qualitative data-collection approach, which included collection of rich data to identify consistent themes, evaluate preference, and confirm the final conceptual model. The P-TRT instrument is suitable for further development and use in future patient-reported outcome studies involving testosterone replacement therapy.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the contributions of Stefan Seman and Peter Choi, assistant researchers at the International Center for Pharmaceutical Economics and Policy, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Boston, MA.

Appendix

|

Directions: Please either mark or circle the number that best describes to what extent each of the following items influences your preference for a testosterone replacement product?

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please tell us how each of the following items influences your preference for a testosterone replacement product | Not influential | Somewhat influential | Influential | Very influential | Extremely influential |

| Location of product application | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Drying time when applied to skin | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Convenience | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No skin rash | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Skin not itchy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on muscle tone | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Effect on sex drive | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sexual desire | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No product odor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Texture is not greasy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Absorption rate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on exercise | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on stamina | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on others (friends, spouse, partner, family) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on energy levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Attitude about self | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Product does not have to be injected | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Product works | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Product use met expectations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Liking the product | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Weight loss from product use | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Feel better | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Easy to apply | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not sticky | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Prefer this product over other TRT options | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Prefer this product over injections | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Impact on testosterone levels | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No skin irritation from use | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No discomfort | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Abbreviation: TRT, testosterone replacement therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Data collection and analysis were supported by a grant from Endo Health Solutions, Chadds Ford, PA.

References

- 1.Araujo AB, Wittert GA. Endocrinology of the aging male. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(2):303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB, Brambilla DJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of androgen deficiency in middle-aged and older men: estimates from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(12):5920–5926. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. EMAS Group. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4241–4247. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhasin S, Basaria S. Diagnosis and treatment of hypogonadism is men. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(2):251–270. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong BS, Ahn TY. Recent trends in the treatment of testosterone deficiency syndrome. Int J Urol. 2007;14(11):981–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, and EAU recommendations. J Androl. 2006;27(2):135–137. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagatell CJ, Bremner WJ. Androgens in men – uses and abuses. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):707–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zitzmann M, Faber S, Nieschlag E. Association of specific symptoms and metabolic risks with serum testosterone in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4335–4343. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall SA, Esche GR, Araujo AB, et al. Correlates of low testosterone and symptomatic androgen deficiency in a population-based sample. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(10):3870–3877. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morales A. Andropause (or symptomatic late-onset hypogonadism): facts, fiction and controversies. Aging Male. 2004;7(4):297–303. doi: 10.1080/13685530400016664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, et al. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):589–598. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travison TG, Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB, et al. A population-level decline in serum testosterone levels in American men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):196–202. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan RS, Cluberson JW. An integrative review on current evidence of testosterone replacement therapy for the andropause. Maturitas. 2003;45(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(03)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2536–2559. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn TN. Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: recent development in three types of best-worst scaling. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):259–267. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson G, Stallberg B, Tornling G, et al. Asthma treatment preference study – a conjoint analysis of preferred drug treatments. Chest. 2004;125(3):916–923. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harpe SE, Szeinbach SL, Caswell RJ, et al. The relative importance of health related quality of life and prescription insurance coverage in the decision to pharmacologically manage symptoms of overactive bladder. J Urology. 2007;178(6):2532–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summers KH, Szeinbach SL, Lenox SM. Preference for insulin delivery systems among current insulin users and nonusers. Clin Ther. 2004;26(9):1498–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fennell C, Sartorius G, Ly LP, et al. Randomized cross-over clinical trial of injectable vs implantable depot testosterone for maintenance of testosterone replacement therapy in androgen deficient men. Clin Endocrinol. 2010;73(1):102–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhoden EL, Morgentaler A. Symptomatic response rates to testosterone therapy and the likelihood of completing 12 months of therapy in clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1):277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser BG. The future of grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(6):836–845. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Victorson DE, Anton S, Hamilton A, et al. A conceptual model of the experience of dyspnea and functional limitations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health. 2009;12(6):1018–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budych K, Helms TM, Schultz C. How do patients with rare disease experience the medical encounter? Exploring role behavior and its impact on patient-physician interaction. Health Policy. 2012;105(2–3):154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goff SL, Mazor KM, Meterko V, et al. Patients’ beliefs and preferences regarding doctors’ medication recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;23(3):236–241. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0470-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Justicia JL, Baro E, Cardona V, et al. Development of a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with allergen-specific immunotherapy in adults: item generation, item reduction, and preliminary validation. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:239–250. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S19219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solky BA, Phillips K, Christenson LJ, et al. Patient preferences for facial sunscreens: a split-face, randomized, blinded trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eton DT, Shevrin DH, Beaumont J, et al. Constructing a conceptual framework of patient-reported outcomes for metastatic hormonerefractory prostate cancer. Value Health. 2010;13(5):613–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giagulli VA, Triggiani V, Corona G, et al. Evidence-based medicine update on testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in male hypogonadism: Focus on new formulations. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(15):1500–1511. doi: 10.2174/138161211796197160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]