Abstract

We have synthesized and evaluated a series of 1,4-disubstituted-triazole derivatives for inhibition of the rat NaV1.6 sodium channel isoform, an isoform thought to play an important role in controlling neuronal firing. Starting from a series of 2,4(1H)-diarylimidazoles previously published, we decided to extend the SAR study by replacing the imidazole with a different heterocyclic scaffold and by varying the aryl substituents on the central aromatic ring. The 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles were prepared employing the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Many of the new molecules were able to block the rNav1.6 currents at 10 µM by over 20%, displaying IC50 values ranging in the low micromolar, thus indicating that triazole can efficiently replace the central heterocyclic core. Moreover, the introduction of a long chain at C4 of the central triazole seems beneficial for increased rNav1.6 current block, whereas the length of N1 substituent seems less crucial for inhibition, as long as a phenyl ring is not direcly connected to the triazole. These results provide additional information on the structural features necessary for block of the voltage-gated sodium channels. These new data will be exploited in the preparation of new compounds and could result in potentially useful AEDs.

Keywords: sodium channels; patch clamp electrophysiology; 1,4-triazoles; rNaV1.6; click chemistry

Voltage gated sodium channels (VGSCs) are membrane protein complexes that allow the passive flow of sodium ions across biological membranes.1 VGSCs open on membrane depolarization, causing further depolarization of the membrane and the initiation of an action potential. As such, VGSCs play a critical role in regulating cellular excitability and controlling many of the physiological processes associated with neuronal activity.2–4 Alterations in the behaviour of VGSCs have been associated in the pathophysiology of epilepsy, a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent unprovoked seizures. These seizures occur when a brief, strong surge of electrical activity affects either one hemisphere (partial seizure) or both hemispheres of the brain (generalized seizure). In particular, mutations in VGSC genes SCN1A (encoding the Nav1.1 α-subunit), SCN2A (encoding the Nav1.2 α-subunit), SCN1B (encoding the auxiliary β1-subunit), SCN3A (encoding the Nav1.3 α-subunit) and SCN9A (encoding the Nav1.7 α-subunit) have been reported in brain tissues of humans with epileptic syndromes.5–8 In animal models of epilepsy, the Nav1.6 sodium channel isoform, which is heavily expressed with the central nervous system, has been shown to be upregulated.9,10 The Nav1.6 isoform is thought to play an important role in controlling neuronal firing. Nav1.6 channels have a particularly low threshold for spike initiation and are abundantly expressed along the axon initial segment (AIS), the site of action potential initiation. They have been shown to contribute to the spike trigger and also to regulate the repetitive discharge properties of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Mice lacking NaV1.6 have lower instantaneous firing rates and maximal firing rates in retinal ganglion cells (GCs).11,12 Impaired Nav1.6 function in SCN8A (encoding the Nav1.6 α-subunit) mutant mice ameliorates seizure harshness in a severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI) mouse model.13,14 In another study, the same mutant mice displayed considerable resistance to the initiation and development of kindling, a well-established model of abnormal plasticity leading to prolonged seizures and to epilepsy.9 It was also found that kindling is associated with higher expression of Nav1.6 sodium channels in hippocampal CA3 neurons. All of these findings suggest that selective pharmacological inhibition of Nav1.6 sodium channels could increase the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs providing them with an improved therapeutic profile.

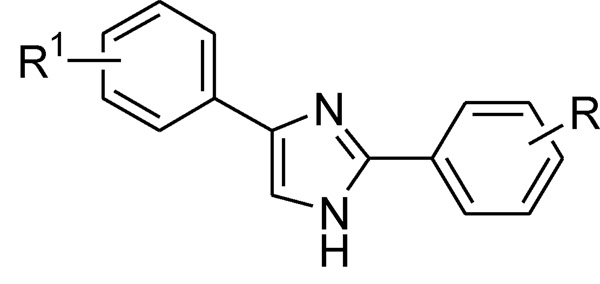

In a recent report, a series of 2,4(1H)-diarylimidazoles were identified as sodium channel blockers (Fig. 1).15,16

Figure 1.

2,4(1H)-Diarylimidazoles

These derivatives carry a central imidazole moiety with two phenyl rings attached to positions 2 and 4, respectively. Different substituents were introduced on each phenyl ring to vary the physico-chemical properties (ionization, lipophilicity, steric hindrance) of the resulting molecules. Some of the compounds presented in those studies had IC50 values within the nanomolar-micromolar range against another neuronal expressed sodium channel isoform, NaV1.2 and showed anticonvulsant activity in an acute in vivo seizure rodent model (MES: Maximal Electoshock Seizure test) with low sedative and ataxic side effects when tested in a rat rotorod test.17

Starting from this interesting series of sodium channel blockers, we decided to extend the SAR study on that class of compounds by replacing the imidazole with a different heterocyclic scaffold and by varying the aryl substituents on the central ring. The SAR analysis of these new series of compounds should provide us with additional information about the structural features necessary to inhibit voltage-gated sodium channels, providing new compounds that may have AED activity. The new molecules were designed by replacing the imidazole ring with a triazole, because of its interesting properties from a medicinal chemistry standpoint, such as good stability to metabolic degradation and a straightforward synthetic route. Interestingly, several drugs contain the 1,2,3-triazole moiety; among them, tazobactam, an inhibitor of bacterial beta-lactamases, various cytostatic and antiproliferative agents and, most importantly, rufinamide, an anticonvulsant medication developed in 2004.18–21

In view of the fact that the NaV1.6 sodium channel has been heavily implicated in epilepsy as well as other common CNS disorders,14 we decided to test these new derivatives (at a concentration of 10 µM) for activity against the Nav1.6 isoform stably expressed in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK 293) cells. We also tested two diarylimidazoles compounds previously shown to have activity against hNaV1.2, on NaV1.6 for comparison purposes.

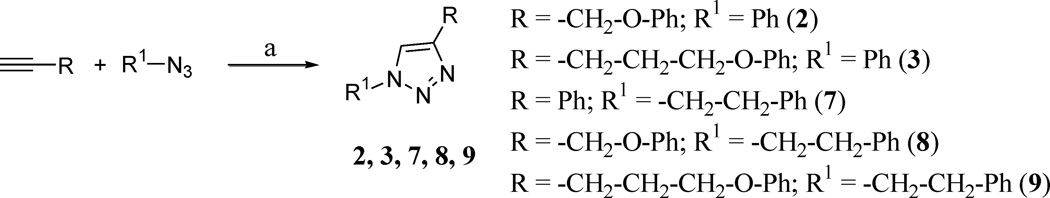

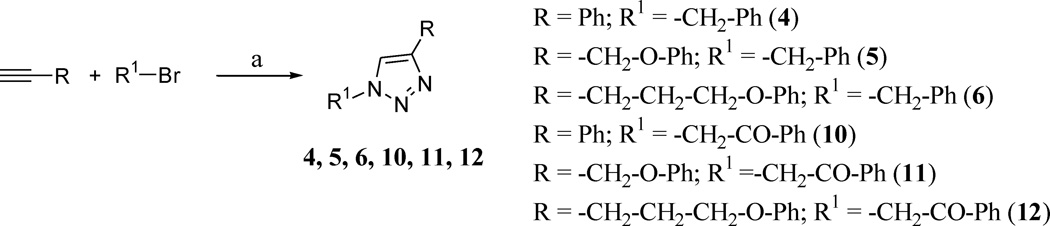

The 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles reported in Table 1 were prepared according to Schemes 1 and 2, employing the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), a widely used synthetic strategy characterized by high efficiency and a simple workup procedure.22,23 With a one-pot reaction, starting from the appropriate alkyne and azido-derivative or bromo-derivative, copper(II) sulfate and sodium ascorbate, used for the in situ generation of Cu(I) catalyst, after heating the reactions mixture overnight at 65 °C in tBuOH/H2O (1:1), we were able to obtain the desired products with yields ranging from 70 to 96% (see Supplementary Data).

Table 1.

Electrophysiological evaluation of compounds 1–14 efficacy against rNaV1.6

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp | R | R1 | Percent block of rNaV1.6 current at 10 µM (n = 4) | IC50 (µM) |

| 1 | 6.2 ± 1.6 | N.D. | ||

| 2 | 16.0 ± 1.0 | 28.5 | ||

| 3 |  |

5.9 ± 1.3 | N.D. | |

| 4 | 10.0 ± 2.1 | 125.4 | ||

| 5 | 11.0 ± 1.7 | N.D. | ||

| 6 |  |

26.0 ± 3.0 | 31.7 | |

| 7 | 11.5 ± 1.5 | N.D. | ||

| 8 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | N.D. | ||

| 9 |  |

22.7 ± 3.1 | 52.0 | |

| 10 |  |

3.9 ± 1.0 | N.D. | |

| 11 |  |

13.6 ± 2.7 | N.D. | |

| 12 |  |

|

22.7 ± 4.5 | 53.6 |

| 13 |  |

16.0 ± 3.5 | 32.2 | |

| 14 |  |

21.7 ± 2.2 | 19.6 | |

N.D.: Not Determined

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) alkyne (2.0 mmol), azido-derivative (2.0 mmol), Na ascorbate (0.5 mmol), CuSO4 (0.025 mmol), tBuOH/H2O (1:1) (6 mL), 65 °C, overnight, 70–88% yields.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) alkyne (2.1 mmol), bromo-derivative (2.0 mmol), NaN3 (2.1 mmol), Na ascorbate (0.5 mmol), CuSO4 (0.1 mmol), tBuOH/H2O (1:1) (6 mL), 65 °C, overnight, 72–96% yields.

Compounds 1–14 were evaluated for their ability to inhibit NaV1.6 sodium channel currents at a concentration of 10 µM (see Supplementary Data).

The 1,4-triazole derivatives 1–12 were screened for activity against the rNav1.6 sodium channel isoform at 10 µM. Table 1 shows the correlation between triazole substitutions and inhibition of rNaV1.6 channel currents. For comparison purposes, we also tested two diarylimidazoles, previously shown to have differing activity against hNaV1.2 (13, 14). At a concentration of 10 µM, compound 13 exhibited a small block of Nav1.2 (7.8%) while compound 14 had a greater block (30.1%). Results reported in Table 1 showed similar behaviour of both compounds 13 and 14 against hNaV1.2 and rNaV1.6 at 10 µM (16.0% block for 13 and 21.7% block for 14). The new triazole derivatives 1–12, synthesized with the aim to study a new central heterocycle with different substituents, inhibited rNaV1.6 currents between 5.8% and 25.9% at 10 µM, thus showing comparable potencies with the diarylimidazole blockers. Dose-response curves were generated for compounds 2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 and the calculated IC50’s are reported in Table 1. IC50 values ranged between 28.5 µM and 125.4 µM. These findings suggest that the presence of a phenyl ring direcly connected to the central triazole is less favorable for inhibition of rNav1.6, as demonstrated by the percent block of compounds 1, 3, 4 and 10. Two exceptions were the phenyl-triazole derivatives 2 and 7, which demonstrated greater inhibition of rNav1.6 currents compared to the previous compounds. An interesting pattern can be observed by considering the different substituents introduced in position 1 of the triazole. In particular, the substituent in R (phenyl for 1, 2, 3, benzyl for 4, 5, 6; phenylethyl for 7, 8, 9 and phenylethanone for 10, 11, 12) correlates with an increase in inhibitory activity with the lengthening of the chain in the substituent at position 4 (R1). In fact, as shown in Table 1, the most potent molecule for each group possesses a phenoxypropyl-chain in R1 (6, 9 and 12). Nevertheless, considering the first group (compounds 1, 2, 3), it is possible to observe that compound 2, having a phenoxymethylchain, is the most active, behaving as an outlier. The three phenoxypropyl-derivatives (6, 9 and 12) display comparable inhibitory activity against rNav1.6 currents, independently of the substituent carried on position 1 of the triazole ring.

The copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) was employed to prepare 1,4-triazoles derivatives with different aryl substituents at the N1 and C4 positions. Although none of the newly synthesized compounds resulted in more active compounds compared to the reference compounds 13 and 14 at inhibiting rNav1.6 sodium channels, most of them were able to inhibit rNav1.6 currents at 10 µM by more than 20%. The newly synthsized sodium channel blockers displayed IC50 values that were in the micromolar concentration range, indicating that triazole can efficiently replace the central heterocyclic core. Moreover, the introduction of a long chain at C4 of the central triazole seems beneficial rNav1.6 current inhibition, whereas the length of N1 substituent seems less crucial for this activity, as long as a phenyl ring is not direcly connected to the triazole. These results provide additional informations on the structural features necessary for the block of the voltage-gated sodium channels. These new data could be useful on the design of future candidate therapeutics. Activity against Nav1.6 may lead to the generation of more effective and better tolerated anticonvulsant drugs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Centro Interdipartimentale Misure of the University of Parma for providing the NMR instrumentation. Funding from the National Institutes of Health NINDS R21NS061069-02 (M.K.P.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

References and notes

- 1.Ashcroft FM. Nature. 2006;440:440. doi: 10.1038/nature04707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. J. Physiol. 1952;117:500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA. Neuron. 2000;26:13. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuliani V, Fantini M, Rivara M. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;7:962. doi: 10.2174/156802612800229206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantegazza M, Curia G, Bigini G, Ragsdale DS, Avoli M. Lancet. Neurol. 2010;9:413. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitaker WR, Faull RL, Dragunow M, Mee EW, Emson PC, Clare JJ. Neuroscience. 2001;106:275. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu R, Thomas EA, Gazina EV, Richards KL, Quick M, Wallace RH, Harkin LA, Heron SE, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, Mulley JC, Petrou S. Neuroscience. 2007;148:164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuliani V, Patel MK, Fantini M, Rivara M. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:396. doi: 10.2174/156802609788317856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hargus NJ, Merrick EC, Nigam A, Kalmar CL, Baheti AR, Bertram EH, III, Patel MK. Neurobiology of disease. 2011;41:361. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldin AL. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:871. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Wart A, Matthews G. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:7172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1101-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royeck M, Horstmann M-T, Remy S, Reitze M, Yaari Y, Beck H. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2361. doi: 10.1152/jn.90332.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin MS, Tang B, Papale LA, Yu FH, Catterall WA, Escayg A. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2892. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenfeld H, Lampert A, Klein JP, Mission J, Chen MC, Rivera M, Dib-Hajj S, Brennan AR, Hains BC, Waxman SG. Epilepsia. 2009;50:44. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivara M, Baheti AR, Fantini M, Cocconcelli G, Ghiron C, Kalmar CL, Singh N, Merrick EC, Patel MK, Zuliani V. Bioorg. & Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:5454. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fantini M, Rivara M, Zuliani V, Kalmar CL, Vacondio F, Silva C, Baheti AR, Singh N, Merrick EC, Katari RS, Cocconcelli G, Ghiron C, Patel MK. Bioorg. & Med. Chem. 2009;19:3642. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuliani V, Fantini M, Nigam A, Stables JP, Patel MK, Rivara M. Bioorg. & Med. Chem. 2010;18:7957. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanghvi SY, Bhattacharya BK, Kini GD, Matsumoto SS, Larson SB, Jolley WB, Robins RK, Revankar GR. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:336. doi: 10.1021/jm00163a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hupe DJ, Boltz R, Cohen CJ, Felix J, Ham E, Miller D, Soderman D, Van Skiver D. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:10136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Micetich RG, Maiti SN, Spevak P, Hall TW, Yamabe S, Ishida N, Tanaka M, Yamazaki T, Nakai A, Ogawa K. J. Med. Chem. 1987;30:1469. doi: 10.1021/jm00391a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakimian S, Cheng-Hakimian A, Anderson GD, Miller JW. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007;8:1931. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.12.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katritzky AR, Zhang Y, Singh SK. Heterocycles. 2003;60:1225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hein JE, Fokin VV. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1302. doi: 10.1039/b904091a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.