Abstract

Background

Parental behavior described as “scaffolding” has been shown to influence outcomes in at-risk children. The purpose of this study was to compare maternal verbal scaffolding in toddlers born preterm and full term.

Methods

The scaffolding behavior of mothers of toddlers born preterm and healthy full term was compared during a 5 minute videotaped free play session with standardized toys. We compared two types of scaffolding and their associations with socio-demographic, neonatal medical factors, and cognition.

Results

The mothers of toddlers born full term used more complex scaffolding. Maternal education was associated with complex scaffolding scores for the preterm children only. Specifically, the preterm children who were sicker in the neonatal period, and whose mothers had higher education, used more complex scaffolding. In addition, children born preterm who had less days of ventilation, had higher cognitive scores when their mothers used more complex scaffolding. Similarly, cognitive and scaffolding scores were higher for children born full term.

Discussion

Our findings highlight early differences in mother-child interactive styles of toddlers born preterm compared to full term. Teaching parents play methods that support early problem solving skills may support a child’s method of exploration and simultaneously their language development.

Keywords: Cognition, Maternal Education, Maternal Scaffolding, Preterm

Introduction

It is well documented that children born preterm are at high risk for neurodevelopmental challenges, including cognitive, attention, and self-regulation difficulties.1 These difficulties have also been shown to persist throughout childhood and are associated with an increased incidence of learning and attention difficulties as well as behavioral problems.2

In the past several years, there has been, not only, an increased interest in identifying the neurodevelopmental outcomes faced by children born preterm, but also in identifying what factors are associated with more optimal outcomes in order to target early intervention efforts.3 Parental behaviors and their associations with child outcomes have been a key focus within prevention strategies, particularly given the essential role parents play in intervention efforts.

One parenting behavior that has gained recent interest, and has been shown to influence outcomes in at-risk children, is parental scaffolding.4 According to the sociocultural theory of development,5 scaffolding occurs when parents provide children with the support necessary for them to accomplish goals that otherwise would be beyond their ability. Through parents’ scaffolding efforts, children gradually learn more developmentally advanced skills and become better able to solve problems independently.

Recent studies have focused on the role of verbal scaffolding, which comprises the verbal prompts parents provide children to help them solve problems or help them understand conceptual links between objects and/or activities.6 These studies have highlighted how important the content of parents’ verbal input is for children’s learning, showing that higher levels of verbal scaffolding during early childhood is predictive of better language,4, 7 nonverbal problem-solving,4 reading,7 cognitive,8 and executive functioning skills4 during school years.

The purpose of the current study was to examine and compare maternal verbal scaffolding in toddlers born preterm and full term. Of particular interest was whether there are differences in the level of verbal scaffolding (i.e., simple versus complex) used in these group and the relationship between each level of scaffolding and children’s cognitive skills. In addition, this study sought to examine which socio-demographic and neonatal medical factors are associated with each type of verbal scaffolding for the preterm and full term groups. We hypothesized that mother’s of infants born preterm would use less verbal scaffolding and that mothers with higher education levels would use more scaffolding across both groups.

Methods

Subjects and procedures

The study consisted of children between the ages of 18 and 22 months and their mothers. Children were born between 2005 and 2008. Children born preterm were recruited from the developmental follow-up clinic of the University of New Mexico’s Newborn Intensive Care Unit. The full-term group was recruited through the University of New Mexico’s Pediatric Clinic. Eighty-four children born preterm (specifically, birth weights of less than 1500 grams and born at less than 32 weeks gestation) and sixty-four children born full term participated. The study was approved by the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee and permission was obtained from a legal guardian prior to participation. Age at testing was adjusted for gestational age for the preterm group. Infants were excluded from the study if they had been prenatally exposed to drugs, were visually/hearing impaired, had a known genetic abnormality, constituted a multiple birth, and/or did not reside with their biological families. We excluded one child who was preterm and severely impaired, and therefore could not engage in play.

Play, Cognitive Measures and Medical/Social Variables

Verbal Scaffolding Scale9

Child and mother dyads were videotaped for 10 minutes with a standard set of toys. Parents were told that the video tapes were to help determine best ways for mother’s to play with their children, which may inform early interventions for children born preterm. Five minutes of the videotaped mother-child interaction was used for coding purposes. Verbal scaffolding coding, using the Verbal Scaffolding Manual,9 was based on the content of the mothers’ verbal message to the child. Maternal statements were considered to be a scaffolding statement if it helped the child make associations or provided strategies to help the child solve a problem. The scaffolding statements were then categorized as “simple” or “complex.” Simple scaffolding included statements whereby the mother used a noun and verb together during play or mimicked the child’s activity (e.g., mom labels her action or the action the child is performing). Complex scaffolding included statements that involved associating an object with a specific location, using ‘like that’ comparisons, describing objects (apples are red), and defining the uniqueness or features of an object or the specific function of an object. Other categories of complex scaffolding included defining cause and effect, emotions, senses, contrasts, categories of objects, and linking nouns with nouns. The total of simple and complex scaffolding score is referred to as the combined scaffolding score. Tapes were coded by three coders (first author and two graduate students) who maintained 90% inter-reliability. The tapes were coded by two coders who obtained consensus, and a third coder, re-coded every tenth tape.

The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development

The Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II10 (BSID-II) was used to assess cognitive development for those children tested prior to 2005. The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-III11 (BSID-III) was used for the children tested after 2005. To have a comparable cognitive measure for both groups, we transformed the BSID-II mental developmental index to a BSID-III cognitive score based on a conversion formula.12

Medical/Social Variables

The number of days on a ventilator was used as a measure of illness severity.13 Maternal education was included as an independent variable and proxy for socioeconomic status. These variables were included to measure the impact of both medical and social factors on cognition and maternal play style.

Statistical Analysis

Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon two-sample tests were used to test for differences between the preterm and full term groups on socio-demographic variables due to non-Gaussian distributions for some variables. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to measure differences in ethnicity and scaffolding scores. Spearman rank correlations ρ were computed to measure the association between scaffolding (simple, complex and combined) play scores for preterm and full term groups. Conditioning plots14 were constructed in the statistical package R15 to better understand the multivariable nature of the associations between the developmental, medical and social variables. Conditioning plots were used since scaffolding scores had discrete distributions with tied scores and the standard theory of least squares was violated. We divided the preterm group by days of ventilation (median split) to better understand the impact of illness severity on scores and associations, i.e. conditioned on illness severity. A median split of 15 days on ventilation was used (n=45 for low ventilation group and n=46 for high ventilation group).

Results

Patient characteristics and medical data

Significant group differences were found for child’s age at testing, with the preterm children being older based on their adjusted age at testing. Maternal education, maternal age, family income, and gender were not significantly different for the two groups. The preterm group had significantly lower birth weight and significantly lower BSID-III cognitive scores. The mothers of children born full term used significantly more complex scaffolding and combined scaffolding (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Preterm and full term groups.

| Preterm n= 84 | Full Term n= 67 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Factor | Mean (SD) Range |

Mean (SD) Range |

P-value |

| Test Age (months) | 20.2 (1.3) 17-23 months |

19.6 (1.6) 17-23 months |

p=0.02 |

|

| |||

| Birth weight (grams) | 939.4 (228) 550-1500 |

3336.4 (488.2) 2470-4580 |

p<0.001 |

|

| |||

| Maternal age (years) | 27.4 (8.6) 17-45 |

28.2 (6.1) 18-40 |

p=0.46 |

|

| |||

| Gender Male | 52% | 58% | p=0.74 |

| Child Ethnicity | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | p=0.02 |

| White | 18 (22%) | 19 (28%) | |

| Native American | 21 (25%) | 5 (8%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 42 (50%) | 42 (62%) | |

| other | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

|

| |||

| ◆ Maternal Education | 1.7 (1.5) 0-6 |

2.1 (2.0) 0-6 |

p=0.21 |

|

| |||

| □ Household Income | 1.9 (1.9) 0-7 |

2.6 (2.6) 0-7 |

p=0.06 |

|

| |||

| Cognitive Score | 96.7 (9.9) 70-116 |

105.0 (7.1) 93-123 |

p<0.001 |

|

| |||

| Complex Scaffolding | 1.7 (2.5) 0-10 |

3.1 (2.8) 0-10 |

p<0.001 |

|

| |||

| Simple Scaffolding | 2.2 (2.0) 0-8 |

2.1 (1.6) 0-6 |

p=0.67 |

|

| |||

| Total Scaffolding | 4.0 (3.0) 0-12 |

5.2 (3.5) 0-14 |

p=0.02 |

0-<H.S., 1- H.S. graduate; 2- HS+ 1 yr college; 3-Associate degree; 4-Bachelor degree; 5- Some graduate school, 6- Masters degree +

0-<10,000; 2- 10,000-20,000; 3-20,000-30,000; 4-30,000-40,000; 5-40,000-50,000; 6-60,00070,000; 7-70,000+

Verbal scaffolding and maternal education, cognition and illness severity

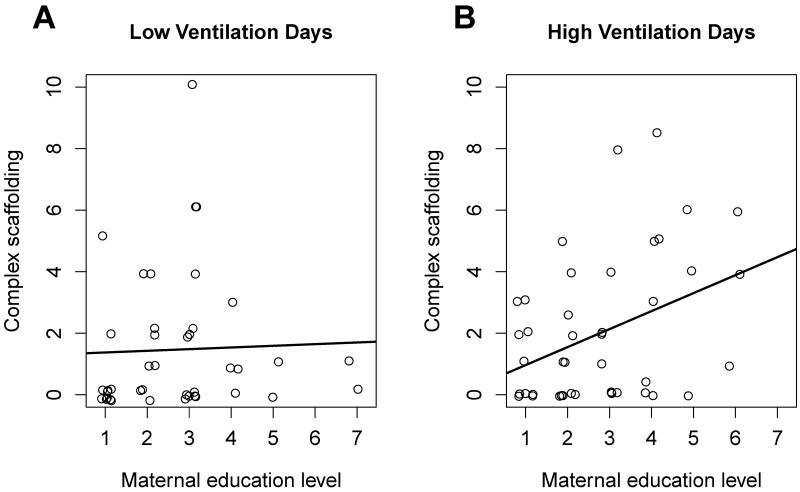

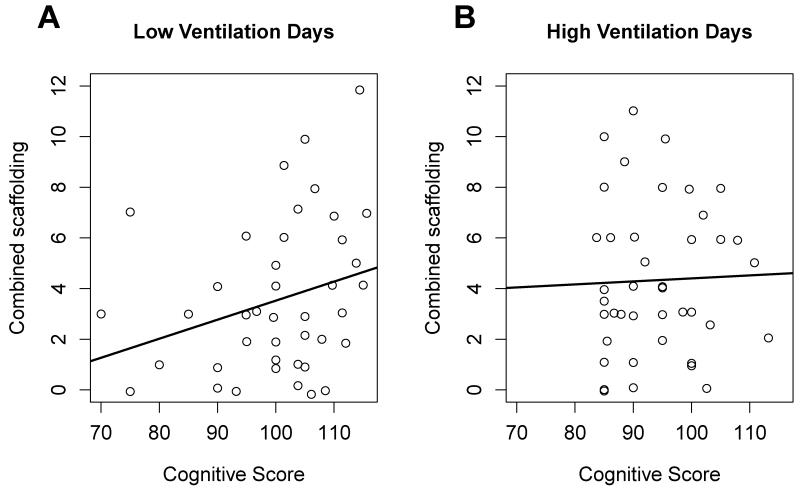

Maternal education was significantly associated with complex (ρ=.22, p=0.04) and combined scaffolding scores (ρ=.25, p=0.02) for the preterm children only. Preterm children were divided into low and high ventilation groups to better understand the association of illness severity on scaffolding scores. Complex scaffolding was significantly positively associated with maternal education level for those mothers who had preterm children in the high ventilation group (ρ =.33, p=0.03); that association did not hold for those mothers who had preterm children in the low ventilation group (see Figure 1). There was no significant association with scaffolding and cognitive scores for the preterm group. However, when the preterm group was divided by illness severity, the children in the low ventilation group had a significantly positive association between cognitive scores and combined scaffolding (ρ=.30, p<0.05; Figure 2). That relationship did not hold for the high ventilation group.

Figure 1.

Plot of complex scaffolding vs. maternal education level conditional on ventilation days for preterm children. Panel A shows those children with low number of days on ventilation did not have an association between maternal education and complex scaffolding score. Panel B shows those children with high number of days on ventilation had a significant association between maternal education and complex scaffolding score (p=0.02). The lines in the panels are simple least squares fits to the data. Due to numerous tied values points were ‘jittered’ by adding a small amount of random noise to see the actual numbers of points; p values and summary scores were all calculated on original data.

Figure 2.

Plot of combined scaffolding vs. cognitive score conditional on ventilation days for preterm children. Panel A shows those children with low number of days on ventilation had a significant association (as measured by Spearman correlation) between cognitive score and combined scaffolding score (p=0.04). Panel B shows those children with high number of days on ventilation had no association between cognitive score and combined scaffolding score. The lines in the panels are simple least squares fits to the data. Due to numerous tied values points were ‘jittered’ by adding a small amount of random noise to see the actual numbers of points; p values and summary scores were all calculated on original data.

In contrast to the children born preterm, those born full term had a significant positive association between Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development cognitive score with simple scaffolding (ρ=.26, p=0.04) and combined scaffolding (ρ=.34, p=0.006). No association was found between ethnicity or gender and the simple or combined scaffolding scores for either the preterm or full term groups.

Discussion

Our study highlights early differences in mother-child interactive styles of children born preterm compared to those born full term, specifically with regards to maternal scaffolding behaviors. We found that mothers of children born full term used significantly more complex scaffolding behaviors in contrast to mothers of preterm children. This difference may reflect a process by which mothers adjust their scaffolding based on their perception of their child’s developmental level. Because the preterm group had significantly lower developmental levels compared to the full term sample, as indexed by the Bayley scores, it is possible that in our sample the mothers of children born preterm were attuned to this difference and, hence, adjusted their scaffolding in order to be sensitive to their child’s level of understanding. If this is the case, however, it is unclear whether using less complex scaffolding is helpful to the children born preterm.

Interestingly, a previous study by Donahue and Pearl16 compared the verbal input provided by mothers of children born preterm and full term during problem-solving tasks. They found that, similar to our findings, mothers of children born preterm used less complex verbal input, thereby providing less complex verbal scaffolding to their children. Since there are few studies that have compared scaffolding in these populations, it will be important that future studies examine whether mothers of children born preterm are appropriately “fine-tuning” their verbal input in order to be sensitive to their children’s needs or whether this may be related to a type of prematurity stereotyping whereby mother’s adjust their input solely based on their child’s prematurity.

Our study also found that verbal scaffolding was related to cognitive skills for the children born full term and the preterm children who were less ill (required less ventilation) during the neonatal period. The finding that scaffolding is related to higher functioning in a range of domains is not unexpected as this has been demonstrated in previous studies.4, 7, 8 Landry and colleagues,4 for example, found that among mothers of three-year-old children born preterm and full term, verbal scaffolding was associated with higher functioning in both verbal and non-verbal problem solving at four years as well as increased executive functioning at 6 years for both full term and preterm born children.

Interestingly, a recent study by Hammond and colleagues17 found that the relationship between scaffolding and early executive functioning depended on the child’s age. In their study of healthy full term children, scaffolding at two years of age was not related to early executive functioning skills at three years, however, scaffolding at 3 years of age was associated with executive functioning at 4 years of age. Although speculative, it is possible that scaffolding has a different relationship with cognition and early executive function at different ages for preterm and full term born children. This may be particularly true given the difference in the developmental level of both groups, as children born preterm are known to have significantly lower cognitive and executive functioning skills.1, 18, 19 Examining this association at different ages in both groups could help us better understand this relationship.

Although we expected to find a relationship between complex scaffolding and maternal education across both groups, we only found this relationship in the preterm group. Within the preterm group, mothers with higher education used more complex scaffolding and combined scaffolding. Although the relationship between scaffolding and education does not appear to have been previously assessed in preterm groups, studies examining this relationship in full term samples have found an association between education and scaffolding.20 It is possible that in the full term group the relationship between scaffolding and maternal education was not found because these mothers were already using more complex scaffolding. In contrast, in the preterm group, the mothers with higher education may have been using more complex scaffolding since they were more aware of the importance of scaffolding for the optimal development of their children compared to mothers with less education. Studies examining the relationship between maternal education and play interactions support this by showing that mothers with higher education appear to be more knowledgeable about play styles that enhance learning.21

Within the preterm group, mothers with higher education who had sicker preterm infants (i.e., high ventilation group) used significantly more complex scaffolding behavior. This finding within the preterm children may highlight the increased need of these children. Mothers with higher education may be more aware of the need that their children have, particularly if they were considered more at risk of having neurodevelopmental difficulties. As a result, they may try to compensate by providing more scaffolding for their child in order to help their development. Although not assessed in this study, this potential process of compensation may be related to the perception of child vulnerability that the mother holds for her child, in that mothers who perceive their child as more vulnerable may be more prone to helping their child during interactions.22 Interestingly, within the child vulnerability literature, maternal education has often been found to be positively associated with child vulnerability perceptions, as scaffolding was in this study. The link between scaffolding and maternal education, within the more vulnerable children born preterm, is particularly important given that Koldewijn and colleagues23 recently showed that maternal education is an important factor associated with improved cognitive outcomes among children born preterm receiving neurobehavioral intervention. Furthermore, they highlighted the particular importance of supportive intervention within the most vulnerable groups of children born preterm in that children born preterm, who were considered most vulnerable due to bronchopulmonary dysplasia, benefited most from intervention.23

A limitation of this study was that it only measured maternal verbal scaffolding and it may have been beneficial to also look at styles of non-verbal scaffolding that occur with mother-toddler interactions. It would have also been useful to assess toddler language skills in addition to cognition, since an association between maternal scaffolding and language skills has previously been found.24, 25 Future studies using the BSID-III could include the language scales to further this line of inquiry. We also did not have information on the early intervention or preschool programs children were enrolled in so could not look at the effect these programs may have had. In addition there may be other medical variables associated with use of maternal scaffolding and/or child cognition (intraventricular hemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity), not included in the current study. Despite limitations, the current study helps us better understand the maternal interaction styles that augment development, hence highlighting potential areas of intervention. This type of an intervention is easy to administer and not costly, but can have lasting effects on both the mother-child relationships and potentially early cognitive skills.

In conclusion, we found an association between mothers’ verbal scaffolding during play and full-term toddlers’ developmental level that could potentially be an effective way to enhance developmental skills of young toddlers born healthy at full term and preterm. Teaching a parent ways to play with their child that utilize early problem solving skills can potentially enhance the child’s development while simultaneously advancing the child’s methods of exploration and play.

Key Notes.

Maternal scaffolding was associated with higher cognition in children born full term. Mothers of children born preterm with higher education used more scaffolding as did mothers of children born full term. Promoting parenting play that uses verbal scaffolding may enhance problem solving skills in children especially those born preterm.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8UL1TR000041, The University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center. The assessments were supported by a grant from the University of New Mexico Pediatric Research Committee. We thank the parents and their children that participated in our study. We thank Susanne Duvall M.S. and Joy Van Meter B.S. for assistance with testing and coding of tapes.

ABBREVIATIONS

- (BSID-II)

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development – 2nd edition

- (BSID-III)

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development – 3rd edition

References

- 1.Mulder H, Pitchford NJ, Hagger MS, Marlow N. Development of executive function and attention in preterm children: a systematic review. Dev Neuropsychol. 2009;34(4):393–421. doi: 10.1080/87565640902964524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spittle AJ, Treyvaud K, Doyle LW, Roberts G, Lee KJ, Inder TE, et al. Early emergence of behavior and social-emotional problems in very preterm infants. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):909–918. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181af8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landry SH, Miller-Loncar CL, Smith KE, Swank PR. The role of early parenting in children’s development of executive processes. Dev Neuropsychol. 2002;21(1):15–41. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2101_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vygotsky LS. The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1978. Mind in society. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Guttentag C. A responsive parenting intervention: the optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(5):1335–1353. doi: 10.1037/a0013030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich SE, Assel MA, Swank P, Smith KE, Landry SH. The impact of early maternal verbal scaffolding and child language abilities on later decoding and reading comprehension skills. J Sch Psychol. 2006;43:481–494. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landry SL, Smith KE, Swank PR, Assel MA, Vellet S. Does early responsive parenting have a special importance for children’s development or is consistency across early childhood necessary? Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(3):387–403. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landry SL. Mother-child coding manual for maternal targeted behaviors, child social responding, child social initiating. 2000. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development, II. Psychological Corporation; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development, III. Psychological Corporation; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe JR, Erickson SJ, Schrader R, Duncan AF. Comparison of the Bayley II Mental Developmental Index and the Bayley III cognitive scale: are we measuring the same thing? Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(2):e55–e5813. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh MC, Morris BH, Wrage LA, Vohr BP, Poole WK, Tyson JE, et al. Extremely low birthweight neonates with protracted ventilation: Mortality and 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Pediatr. 2005;146:798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleveland WS. Visualizing Data. Summit Press; New Jersey: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Development Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: 2012. Available From: URL http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue ML, Pearl R. Conversational interactions of mothers and their preschool children who had been born preterm. J Speech Hear Res. 1995;38(5):1117–25. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3805.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond SI, Muller U, Carpendale JIM, Bibok MB, Liebermann-Finestone DP. The effects of parental scaffolding on preschoolers’ executive function. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(1):271–281. doi: 10.1037/a0025519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchinik LJ, Taylor HG, Espy KA, Minich N, Klein N, Sheffield T, et al. Cognitive outcomes for extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children in kindergarten. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17(6):1067–79. doi: 10.1017/S135561771100107X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aarnoudse-Moens CH, Duivenvoorden HJ, Weisflas-Kuperus N, Van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. The profile of executive function in very preterm children at 4 to 12 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;54:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr A, Pike A. Maternal scaffolding behavior: links with parenting style and maternal education. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(2):543–551. doi: 10.1037/a0025888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J, Rao N. Scaffolding interactions with preschool children: comparisons between Chinese mothers and teachers across different tasks. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2012;58(1):110–140. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan AF, Caughy M. Parenting style and the vulnerable child syndrome. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;22(4):228–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koldewijn K, Wassenaer A, Wolf M, Meijssen D, Houtzager B, Beelen A, Kok J, Nottet F. A neurobehavioral intervention and assessment program in very low birth weight infants: Outcome at 24 months. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;156:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vygotsky LS. Thinking and speech. In: Rieber RW, Carton AS, editors. The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky, Vol.1 Problems of general psychology. Plenum; New York: 1987. pp. 37–285. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernyhough C. Vygotsky, Luria, and the social brain. In: Sokol B, Muller U, Carpendale J, Young A, Iarocci G, editors. Self- and social-regulation: exploring the relations between social interaction, social cognition, and the development of executive functions. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: pp. 56–80. Doi:10.1093/01.psy.0000221275.75056.d8. [Google Scholar]