Abstract

Background

Dorsal herniation of the spinal cord through the dura is an uncommon phenomenon and this is only the fifth reported case in the thoracolumbar spine, the first following surgery at the thoracolumbar junction.

Case

A 57-year-old male underwent marsupialisation of a benign intramedullary cyst at the T12–L1 level and subsequently returned with symptoms of dorsal column compromise. He was found to have a posterior herniation of the cord into a pseudomeningocele at the level of the previous surgery.

Conclusion

The hernia was reduced surgically and the defect closed directly without the need for a dural patch leading to a full recovery. Posterior cord herniation, its possible aetiologies and management strategies are discussed.

Keywords: Spinal cord disorders, Neurenteric cyst, Pseudomeningocele, Hernia

Introduction

Anterior spinal cord herniation remains under reported, but is nonetheless a recognised cause of thoracic myelopathy with a dural defect—either congenital or acquired at surgery or through trauma—proposed as the underlying mechanism [1, 2]. By contrast, posterior or dorsal herniation of the cord through the dura is rare. Only five cases in the cervical spine are reported, all iatrogenic, and four in the thoracic or lumbar spine, two post-traumatic and two into pre-existing cystic lesions [3–9]. Here the authors describe the first case of a posterior herniation of the spinal cord at the thoracolumbar junction, which occurred following surgery to remove an intramedullary cyst.

Case report

A 57-year-old man with a history of essential hypertension presented as an outpatient with symptoms of spinal claudication. He reported 2–3 years of pain radiating down the posterior aspect of both legs, which was worse with activity or standing and relieved by rest and the sitting position. The possibility of peripheral vascular disease had been ruled out previously with duplex arteriography of the lower limbs. On examination, the patient was mobile with a normal gait and there were no focal neurological deficits. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the spine demonstrated an intramedullary cyst at the T12–L1 level (Fig. 1). The patient was offered surgery to treat the cyst with the aim of relieving symptoms of claudication and obtaining a tissue diagnosis. With the patient prone and through a midline incision, bilateral muscle strip and then laminectomy were performed. The dura was opened and edges hitched up with vicryl sutures to expose the pia. No abnormality of the cord or dura was noted. The cyst was marsupialised and closure of the dura was performed with 6–0 prolene sutures in a watertight fashion, checking there was no leak with a valsalva manoeuvre. The wound was closed in layers. The patient was discharged uneventfully on the second post-operative day and the wound was dry. Histopathology subsequently revealed a benign, neurenteric cell type. The patient attended for follow-up 8 weeks following surgery and complained of worsening back pain radiating into the legs. Clinically there was loss of pin prick sensation up to the knees bilaterally, loss of proprioception in the lower limbs and difficulty walking with an ataxic gait. An urgent MRI spine demonstrated posterior displacement of the cord at the level of the original surgery (Fig. 2) with an associated cystic cavity following CSF signal characteristics. On the axial images the cord was seen to be herniated through the site of the original dural incision in the midline. There was no signal change in the cord to indicate compression, but there was evidence of signal change around the margins perhaps indicating some inflammatory process or tethering.

Fig. 1.

Sagittal T2 weighted MRI pre-operatively demonstrating an intramedullary cyst at the thoracolumbar junction later found to be of benign, neuroenteric origin in a 57-year-old male presenting with neurogenic claudication pain

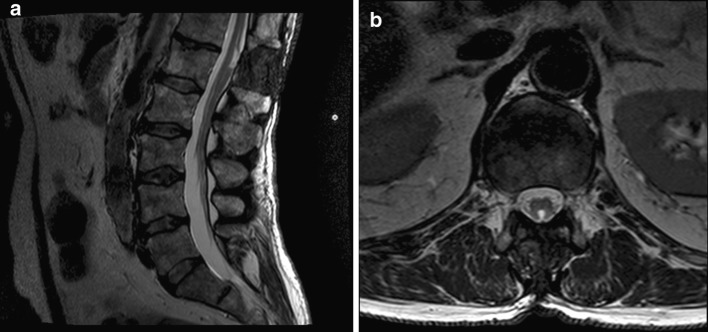

Fig. 2.

The patient presented 8 weeks post-operatively with a sensory level and ataxic gait with loss of lower limb proprioception. He was found to have a herniation of the cord at the previous level of surgery as shown in axial (a) and sagittal (b) T2 weighted MRI scans

The patient underwent urgent surgery and via a posterior approach the thoracolumbar junction was exposed. Intra-operatively a knuckle of herniated cord under extensive fibrous scar tissue was found. There were clear indications of the margins of the previous dural closure but no suture material or point of dehiscence was seen. The cord was dissected away from the scar tissue, the dural defect clearly demarcated and the cord reduced through the dural defect. It was possible to close the dura directly without tension or compression of the cord and no patch or graft was required. The dura was pulsatile at the end and again, there was no leak on valsalva. No drain was placed and the wound closed in layers with vicryl and nylon to skin. The patient made a good post-operative recovery and after a period of inpatient physiotherapy was mobile and discharged. At follow-up 18 months later, the patient was mobile with the aid of a stick. He has ongoing back pain for which he is taking non-opiate pain medications. MRI with contrast (Fig. 3) does indicate some recurrence of the intramedullary cyst but no evidence of herniation and no further surgery is planned.

Fig. 3.

Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T2 weighted MRI at 1-year post-operatively demonstrating resolution of the cord herniation after dural repair and the marsupialised cyst

Discussion

Anterior or ventral cord herniation is well described with an analysis of over 100 cases now reported [2]. It may occur secondary to a congenital or acquired dural defect or as a consequence of trauma or surgery. Posterior cord herniation is rare and this novel report of an occurrence at the thoracolumbar junction is therefore significant because it is not known whether the mechanisms, presentation and management are similar to anterior herniation and whether it is truly less common or simply under reported.

Comparison with previously reported cases

In the cervical spine, six cases of posterior or dorso-lateral cord herniation are reported [3, 5–9] and all of these were post-operative. Four were patients who had specifically undergone opening of the dura at surgery (via posterior laminectomy) and a further two had inadvertent dural opening peri- or post-operatively. The most common presentation was with myelopathy and there was a delay in presentation of up to 18 years from the original operation. Surgical repair yielded improvement in almost all cases.

In the thoracic and lumbar spine, four cases are described and these are summarised in Table 1. One of these is a case with little clinical information in which the patient had a traumatic thoracic injury with extensive syringomyelia; outcomes and interventions are not detailed. A further case is well described by the same authors [3] in which a man having anterior vertebrectomy and instrumented fusion at L1 after trauma developed leg, back pain and sphincter disturbance over the ensuing 10 months. He was found to have a dorsally herniated conus with associated CSF collection and was not improved by surgical correction. Two cases of herniation of the thoracic cord posteriorly into pre-existing arachnoid cysts are described. One case was in a 2-year-old paediatric patient who presented with progressive paraparesis [4]. The other case was a 37-year-old with myelopathy who had undergone a lumbar fixation for spondylolisthesis at a distant site to the herniation [10]. Both underwent surgery via a posterior approach to repair the dura and reduce the herniation. The dural defect was widely expanded in both cases and patched with muscle in one case and dural substitute in the other.

Table 1.

Reported dorsal cord herniations in the thoracic or lumbar spine

| Age/gender | Level of cord herniation | History | Signs and symptoms | Management and outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35/M | T3 with associated syringomyelia | Thoracic trauma 17 years ago | Slowly progressive spastic paraparesis | Unknown | [3] |

| 46/M | L1 | Vertebrectomy and anterior instrumentation 10 months previously | Myelopathy | Surgical reduction—unchanged clinically | [3] |

| 2/M | T3/4 into arachnoid cyst | Deterioration of gait at 1 year old after normal birth and development | Progressive paraparesis | Surgical reduction, dural patch graft—improved at 2 years | [4] |

| 37/M | T8/9 into arachnoid cyst | L5–S1 fixation 5 years previously | Progressive paraparesis | Surgical reduction, dura covered over with muscle—gait improved | [10] |

| 57/M | T12/L1 | Intramedullary cyst excised 8 weeks previously | Dorsal column dysfunction and gait disturbance | Surgical repair—gait improved, pain continues at 1.5 years | Current case |

Presentation and management

When our patient re-attended he was re-assessed and up to date imaging in the form of an MRI scan was obtained leading to prompt treatment. Given the appearance of the cord at surgery left untreated, one might expect vascular compromise of the cord to eventually occur and repair was undertaken urgently. As in previously reported cases, this patient has done well following surgical reduction of the hernia and closure of the dural defect. No dural patch or substitute was used as the dura was felt to be slack at surgery, but it will be noteworthy if this leaves the repair under tension and leads to recurrence in the future; this has not occurred thus far.

Possible mechanisms for posterior herniation

A dural defect of some sort is clearly a pre-requisite for cord herniation and in this instance the defect through which the hernia occurred was created at the previous surgery. There was nothing atypical about the surgery with regards to the size of dural opening or sutures used and closure was performed in a watertight fashion with no CSF leak post-operatively. It is unclear whether the original cyst contributed to the herniation in any way and we note the association with arachnoid cysts in two previous cases [4, 10] as well as the suggestion on follow up that the cyst may be recurring. We speculate that at some stage following discharge the cord began to herniate through the iatrogenic dural defect, either due to failure of the closure or excessive force or both. The cord may have become adherent to dura or simply had its position in the canal altered by the removal of the intramedullary cyst. Once in contact the flexion/extension of the spine could have driven the cord through the defect. The thoracolumbar junction is a stress riser, due to the movement of the relatively fixed thoracic cage above the lumbar spine and it is possible that the closure was under more posterior force than it would have been at another level. It is of note that posterior herniations have thus far been more widely reported in the cervical spine, where the natural lordosis and dorsal lie of the cord may lead to dorsally directed forces on a dural defect that has been created by surgery or trauma [3, 5–7, 9].

Once a herniation has begun to occur, it would be difficult for CSF to drain around this region and further swelling and incarceration could occur, accounting for the gradual onset of symptoms. The implications and role of impaired CSF flow have been discussed for ventral herniations [11] and are similar to the arguments around the aetiology of syringomyelia in Chiari. A difference in CSF pressure between the rest of the cord and the herniated part would be expected and the pulses of CSF pressure in the spine could alter blood flow and fluid movement [12], thus worsening the cord oedema and herniation. In support of this the edges of the dural margin around the herniation were seen to be hyperaemic and inflamed both macroscopically and on imaging before surgery. MRI phase-contrast CSF would undoubtedly be an informative investigation in future cases to better understand the role of CSF dynamics in the aetiology.

Conclusions

Posterior spinal cord herniation is a rare phenomenon but may theoretically occur in any case where a posterior dural defect is created at surgery. It should therefore be considered if there is any change in neurology or symptomatology of a postoperative patient in such cases and MRI obtained with axial cuts through the level of the dural defect. If diagnosed, prompt surgical reduction of the hernia is advised as in this instance, to prevent neurological deterioration and potentially reverse any deficit. The literature suggests long-term recurrences may occur and therefore patients should be followed closely.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.White BD, Tsegaye M. Idiopathic anterior spinal cord hernia: under-recognized cause of thoracic myelopathy. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18(3):246–249. doi: 10.1080/02688690410001732670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groen RJM, Middel B, Meilof JF, et al. Operative treatment of anterior thoracic spinal cord herniation: three new cases and an individual patient data meta-analysis of 126 case reports. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(3 Suppl):145–159. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000327686.99072.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watters MR, Stears JC, Osborn AG, et al. Transdural spinal cord herniation: imaging and clinical spectra. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(7):1337–1344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nejat F, Cigarchi S. Posterior spinal cord herniation into an extradural thoracic arachnoid cyst: surgical treatment. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2006;104:210–211. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.104.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizuno J, Nakagawa H, Iwata K. Postoperative spinal cord herniation diagnosed by metrizamide CT: a case report. No Shinkei Geka. Neurol Surg. 1986;14(5):681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman SJ, Gregorius FK. Cervical pseudomeningocele after laminectomy as a cause of progressive myelopathy. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc. 1974;39(3):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn V, Smoker WR, Menezes AH (1987) Transdural herniation of the cervical spinal cord as a complication of a broken fracture-fixation wire. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 8(4):724–726 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Cobb C, Ehni G. Herniation of the spinal cord into an iatrogenic meningocele. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1973;39(4):533–536. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.39.4.0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burres KP, Conley FK. Progressive neurological dysfunction secondary to postoperative cervical pseudomeningocele in a C-4 quadriplegic. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1978;48(2):289–291. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.48.2.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin G. Spinal cord herniation into an extradural arachnoid cyst. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7(4):330–331. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1999.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najjar MW, Baeesa SS, Lingawi SS. Idiopathic spinal cord herniation: a new theory of pathogenesis. Surg Neurol. 2004;62(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine DN. The pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with lesions at the foramen magnum: a critical review of existing theories and proposal of a new hypothesis. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220(1–2):3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]