Abstract

From plants to humans, the ability to control infection at the level of an individual cell – a process termed cell-autonomous immunity – equates firmly with survival of the species. Recent work has begun to unravel this programmed cell-intrinsic response and the central roles played by IFN-inducible GTPases in defending the mammalian cell’s interior against a diverse group of invading pathogens. These immune GTPases regulate vesicular traffic and protein complex assembly to stimulate oxidative, autophagic, membranolytic and inflammasome-related antimicrobial activities within the cytosol as well as on pathogen-containing vacuoles. Moreover, human genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and disease-related transcriptional profiling have linked mutations in the Immunity-Related GTPase M (IRGM) locus and altered expression of Guanylate Binding Proteins (GBPs) with tuberculosis susceptibility and Crohn’s colitis.

Introduction

Essentially all diploid cells are endowed with a capacity for self defense. This type of host resistance, called cell-autonomous immunity, is ubiquitous throughout both plant and animal kingdoms (Beutler et al., 2006). It is operationally defined by a minimal set of germline-encoded antimicrobial defense factors that enables an infected host cell to resist a variety of prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathogens. In this respect, it functions not only in cells of the immune system, but also in histogenetic lineages as diverse as keratinocytes, endothelia, cardiac myocytes, hepatocytes, enterocytes, astrocytes, tonsillar epithelia, fibroblasts and neurons. Most importantly, cell-autonomous immunity spans both the sensory apparatus used for microbial detection as well as the effector mechanisms directly responsible for microbial killing (MacMicking, 2012; Yan and Chen, 2012).

Given its evolutionary significance, it is remarkable how often this form of somatic host defense is either overlooked or underappreciated, but it remains obligate for host survival, especially in lower organisms where it serves as the primary if not sole form of pathogen resistance (Medzhitov et al., 2012; Ronald and Beutler, 2010). Much of that resistance relies on a pre-existing RNA and protein repertoire mobilized within minutes of infection (Yan and Chen, 2012). This basal repertoire is capable of conferring cell-autonomous protection against a variety of phytopathogens and a more limited set of metazoan pathogens (Ronald and Beutler, 2010).

Once we move to higher species such as mammals, a second mode of cell-autonomous immunity begins to emerge as a likely consequence of the broader microbial challenge faced by many chordates such as humans (Sabeti et al., 2006). This gene repertoire differs from the hardwired circuitry of its predecessor by the characteristic of inducibility. Here a new set of proteins are transcriptionally elicited by activating stimuli such as cytokines and microbial products, a response that is often more sustained and expansive than that of its earlier counterpart, enlisting hundreds of antimicrobial genes (MacMicking, 2012; Yan and Chen, 2012).

Chief among the activating stimuli which remodel the mammalian cell’s transcriptome is the interferon (IFN) cytokine family. IFNs serve as powerful signals for marshaling host defense throughout the vertebrate kingdom. These cytokines induce numerous gene families that encode effectors and associated regulators to direct each protein’s microbicidal or static activity (MacMicking, 2012). Prominent within this group is an IFN-inducible GTPase superfamily that operates against several microbial classes (MacMicking, 2004; Martens and Howard, 2006; Taylor et al., 2004). Over the past few years, we have begun to understand how some of these new IFN-inducible GTPases execute their functions as part of a potent host defense program in several vertebrate species. Likewise, disease-associated genetic variants have recently surfaced within the human population that may predispose to tuberculosis (TB) and Crohn’s disease. This updated review highlights progress on these IFN-inducible GTPases and examines their role at the interface of several host-pathogen relationships.

The IFN-inducible GTPase Superfamily

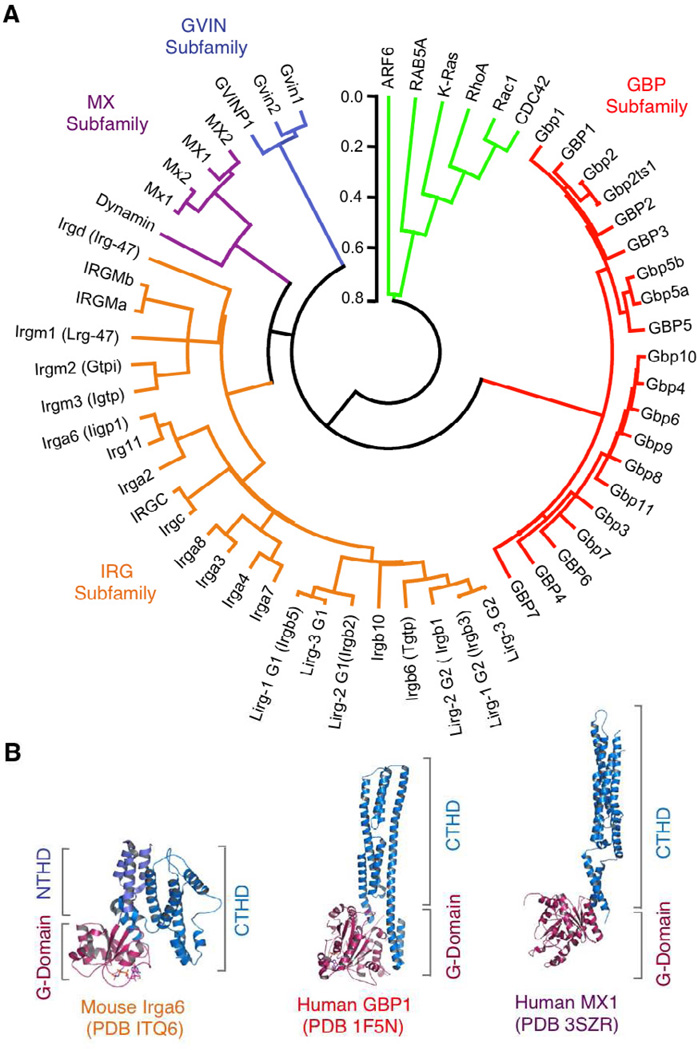

Bioinformatic analysis coupled to chromosomal mapping recently led to assembly of the complete superfamily in two mammalian species – humans and mice (Kim et al., 2011) (Figure 1). This particular effort utilized pair-hidden Markov model algorithms plus cosmid and BAC fragment hybridization to validate members of this family. It built on the pioneering work of Bekpen et al (2005) and some excellent in silico annotations for two IFN-inducible GTPase subfamilies, notably Immunity-Realted GTPases (IRGs) and Guanylate Binding Proteins (GBPs) (DeGrandi et al., 2007; Kresse et al., 2008; Olszewski et al., 2006; Shenoy et al., 2008). Besides humans and mice, IFN-inducible GTPase annotations have now been compiled for other primates plus cows, dogs, rats, opossums, cartilaginous fish, frogs, lizards, birds and cephalochordates such as Brachiostomata (Bekpen et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009). Further studies have unearthed sporadic ancestral orthologs as far back as Arabidopsis (eg. AEC09593; Lin et al., 1999), suggesting resistance functions in these lower organisms that have been refashioned in vertebrates to respond to cytokine stimulation (MacMicking, 2012).

Figure 1. The IFN-inducible GTPase Superfamily in Humans and Mice.

(A) Phylogenetic tree of the IFN-inducible GTPase superfamily encompassing the four subfamilies: 21–47kDa IRGs, 65–73kDa GBPs, 72–82kDa MX proteins and the ~200–285kDa GVINs. Bracketed names depict former assignations prior to the currently adopted HUGO nomenclature. Two IRGM and Gbp5 isoforms included, along with a Gbp1 (Gbp2ts1) transpliced isoform (Kim et al., 2011). Selected H-Ras and dynamin GTPases shown for G-domain comparison (EGA package MEGA v4.0.). Scale bar, substitutions/site.

(B) Structural models of prototypic IRG, GBP and MX proteins based on crystallographic deposits showing the overall bidomain organization composed of an N-terminal G-domain (GD) and C-terminal helical domain (CTHD). In the case of murine Irga6, a short intervening N-terminal helical domain (NTHD) precedes the CTHD. Protein data bank (PBD) codes for the individual proteins are given below.

Currently, the IFN-inducible GTPase superfamily comprises at least 47 members in humans and mice (Kim et al., 2011) (Figure 1). Each GTPase can be grouped into one of four subfamilies on the basis of paralogy and molecular mass. These include the 21–47kDa Immunity-Related GTPases (IRGs), 65–73kDa Guanylate Binding Proteins (GBPs), 72–82kDa Myxoma (MX) Resistance Proteins and ~200–285kDa Very Large Inducible GTPases (VLIGs/GVINs) (MacMicking, 2004; Martens and Howard, 2006).

For the IRG and GBP subfamilies, the majority of genes reside in chromosomal clusters which are syntenic across species (Bekpen et al., 2005; DeGrandi et al., 2007; Kresse et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Olszewski et al., 2006; Shenoy et al., 2008). An exception is the mouse IRG cluster on chromosome 11 where only a single shortened IRGM gene is present on human chromosome 5q33.1 following deletion of the remaining family members by insertion of an ERV9 U3 LTR retroelement (Bekpen et al., 2005, 2009). Here three mouse Irgm loci (Irgm1–3) are replaced by a related prosimian precursor, IRGM9, which through a series of truncation and resurrection events yield the IRGM locus in humans and anthropomorphs such as gorillas and chimpanzees (Bekpen et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Hence the hominoid IRG genes have been heavily trimmed during evolution, although alternative mRNA splicing may partially compensate for this loss by generating several ~21kDa IRGM isoforms (IRGMa, IRGMb, IRGMc/e, IRGMd in humans) with discrete functions (Brest et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2010). The human GVINP1 locus has also undergone some degree of pseudogenization compared with the corresponding murine Gvin genes (Klamp et al., 2003). In most other cases, however, gene expansion rather than contraction predominates, probably driven by duplicative events in response to the evolutionary pressure exerted by intracellular pathogens (Shenoy et al., 2008). This has led to high degrees of homology within subfamilies, especially across the catalytic G-domain.

IFN-inducible GTPases: Design and Distribution

Crystal structures for several IFN-inducible GTPases reveal a bidomain architecture consisting of a globular N-terminal G-domain followed by a C-terminal helical domain (CTHD) (Gao et al., 2010; 2011; Ghosh et al., 2004; Prakash et al., 2000) (Figure 1). This configuration allied with biochemical similarities leads to their being grouped together with members of the dynamin-like family of proteins, which in mammals includes dynamins, mitofusions, atlastins, optic atrophy-1 (OPA1) and other dynamin-like proteins (DRPs) (Ferguson and DeCamilli, 2012). This family governs a variety of cellular functions, from budding and fusion of transport vesicles to organelle division and cytokinesis. They normally exhibit high intrinsic rates of GTPase activity (kcat ~2–100 min−1), low µM substrate affinity and nucleotide-dependent self-assembly to generate > 0.5–1 MDa complexes in cells (Ferguson and DeCamilli, 2012). Hence they are “large” GTPases which operate either as mechanoenzymes or as assembly platforms to orchestrate disparate functions. In contrast, the smaller 20–30kDa H-Ras and heterotrimeric G-proteins operate as molecular “switches”, helping relay upstream signals to downstream effectors with each cycle of GTP hydrolysis (Ferguson and DeCamill, 2012; MacMicking, 2004; Martens and Howard, 2006).

While many IFN-inducible GTPases adhere to the self-catalyzing and GTPase-dependent assembly principles of the dynamin family, some do not. For example, the smaller IRG proteins exhibit low intrinsic rates of GTP hydrolysis and are often GDP-bound, suggesting they could enlist guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to displace GDP and possibly GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) to accelerate hydrolysis, like the H-Ras GTPases (Hunn et al., 2008; Papic, 2008; Tiwari et al., 2009; Uthaiah et al., 2003). Alternatively, some IRGs may undergo G-domain dimerization like other non-Ras GTPases to elicit GAP activity (Gasper et al., 2009; Uthaiah et al., 2003). Specific IRG and GVIN genes also encode tandem duplicated GTPase domains (Klamp et al., 2003; Shenoy et al., 2008), which in the case of GVINs lack some of the canonical nucleotide-contact sites normally used for engaging its GTP substrate (Figure 1). Lastly, certain GBPs (eg. GBP5) undergo tetramerization in the absence of GTP hydrolysis, while other GBPs remain monomeric despite robust catalytic activity (Shenoy et al., 2012; Wehner and Herrmann, 2010). Quite a number of GBPs also generate GMP along with GDP, the only known mammalian GTPases to do so (Colicelli, 2004). Hence the IFN-inducible GTPases would appear to defy simple enzymologic classification. They share selected biochemical features of the dynamin protein family in addition to displaying a uniqueness all their own.

Within the C-terminal region a series of amphipathic αhelices are used for protein-lipid as well as protein-protein interactions; this has been shown for both the IRGs and GBPs (Kim et al., 2011; Martens et al., 2004; Tiwari et al., 2009). Specific GBPs also harbor C-terminal CaaX motifs (GBP1, GBP2, GBP5) that can be either completely or patially isoprenylated to provide anchorage to endomembranes on different organelles distributed within the host cell (Britzen-Laurent et al., 2010; Modiano et al., 2005; Tripal et al., 2007). Mutation of these residues often results in dispersal throughout the cytoplasm and can interfere with antimicrobial function, depending on the pathogen and the type of niche in which it resides (Kim et al., 2011; Tietzel et al., 2009; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). N-terminal glycines in some IRGs are also myristoylated to aid membranous attachment, although whether this modification is obligate for cell-autonomous immunity is as yet unknown (Martens et al, 2004; Papic et al., 2008).

All IFN-inducible GTPases with the exception of MX resistance proteins are transcribed in response to type I (primarily IFN-α/β), type II (IFN-γ) and type III IFNs (IFN-λs). MX proteins are elicited by type I and III IFNs but not IFN-γ (Bekpen et al., 2005; Klamp et al., 2003; DeGrandi et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Kresse et al., 2008). Indeed, these IFN-induced GTPases represent some of the most highly expressed IFN-induced target genes; for example, the GBPs account for as much as 20% of all proteins induced by IFN-γ (Martens and Howard, 2006). Moreover, in keeping with their role in cell-autonomous immunity, the IFN-inducible GTPases are expressed in most mammalian cell lineages examined to date, a reflection in part of the widespread distribution of different IFN receptors (MacMicking, 2004; 2012; Taylor et al, 2004). Certain GBPs also respond to TNF-α and IL-1β in human endothelial cells and mouse macrophages, further diversifying the inducible host response (DeGrandi et al., 2007; Tripal et al., 2007). This enables cell-autonomous immunity to intracellular bacteria, protozoa and viruses in diverse cell types and at selected stages of the pathogen life cycle. Many of their antimicrobial effects are facilitated by direct targeting to the pathogen compartment, a characteristic first noted for members of the IRG subfamily.

IRGs Target the Pathogen Vacuole

“Sensing” the Pathogen Compartment

An early model proposed that the 21–47kDa IRGs respond primarily to signals emanating from compartmentalized pathogens (MacMicking, 2004; 2005; Taylor et al., 2004). Such compartments were thought to be structurally diverse, spanning bacterial phagosomes, Chlamydial inclusion bodies and protozoan parasitophorous vacuoles. Detection of microbial, non-microbial or even missing self structures on these compartments would enable IRGs to mobilize their effectors to this site. Thus the IRGs may bridge upstream sensory events with downstream microbicidal activities in a way that helps decode the language of vacuolar pathogen recognition.

Support for this idea came from examining Irgm1 (formerly lipopolysaccharide-responsive gene of 47kDa [LRG-47]) in macrophages infected with M. tuberculosis (MacMicking et al., 2003). M. tuberculosis phagosomes were found to recruit Irgm1 that facilitated IFN-γ-induced fusion of this compartment with microbicidal lysosomes as shown by a series of direct functional assays; such activity was impaired in Irgm1−/− cells (MacMicking et al., 2003). Thereafter, several groups analyzed the traffic of other IRGs and IFN-inducible GTPases to different pathogen compartments.

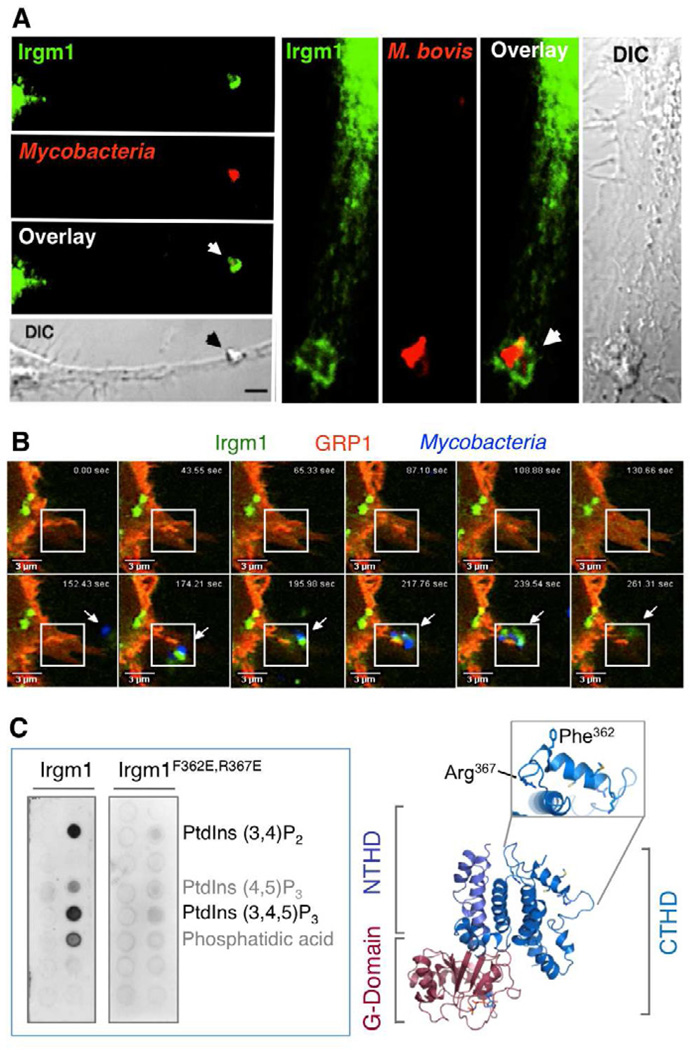

Human IRGM along with its murine Irgm1 ortholog are now known to be targeted to Listeria monocytogenes, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella typhiumurium and most likely Crohn’s disease-associated adherent invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC, which can replicate inside phagolysosomes) in monocytes, macrophages and epithelial cells (Figure 2) (Brest et al., 2011; Gutierrez et al., 2004; Juarez et al., 2012; Lapaquette et al., 2010; McCarroll et al., 2008; Shenoy et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2006; Tiwari et al. 2009). This translocation increases when otherwise cytosolic bacteria remain trapped inside vacuoles (eg. Listeria mutants lacking the pore-forming toxin, listeriolysin O) (Shenoy et al., 2008). Likewise, mouse Irgm3, Irga6 and Irgb10 target inclusion bodies harboring Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia psittaci but not Chlamydia muridarum, suggesting the murine pathogen has coevolved strategies to evade IRG pursuit (Al-Zeer et al., 2009; Coers et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2005).

Figure 2. IRGs Target Intracellular Pathogens.

(A) Irgm1 targets the mycobacterial vacuole. Endogenous Irgm1 (green) translocates to the nascent phagocytic cup (arrows) engulfing Mycobacterium bovis BCG (red) in IFN-γ-activated mouse bone marrow-derived primary (Left) or RAW264.7 (right) macrophages shown by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 2 µm. DIC, differential interference contrast (Tiwari et al., 2009).

(B) Irgm1 recruitment of Irgm1 to the phagocytic cup occurs within minutes of mycobacterial uptake. Live meta-confocal imaging of IFN-γ-activated macrophages expressing fluorescent Irgm1 (green), the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of general receptor for phosphoinositides-1 (GRP1, which detects PtdIns3,4,5P3; red) and M. bovis BCG (in blue with arrow). Boxed region: Irgm1- and PtdIns3,4,5P3-enriched pseudopod engulfing bacteria.

(C) (Left) Robust lipid binding of Irgm1 directly to PtdIns3,4,5P3 and PtdIns3,4P2 in a gel overlay assay that is lost for the Irgm1 αK helical mutant in which amphipathicity of this region is destroyed (Irgm1 F362E,R367E) (Tiwari et al., 2009). (Right) Computer-generated Irgm1 model based on crystallized dimeric Irga6 (PBD code ITQ6) showing the membrane-accessible αK helix and mutated amphipathic residues within it.

Numerous IRGs also converge on vacuoles containing the apicomplexan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, in IFN-γ-activated mouse macrophages, fibroblasts or astrocytes (Hunn et al., 2008; Ling et al., 2006; Khanimets et al., 2010; Martens et al., 2005). The Toxoplasma model has helped reveal sophisticated molecular strategies used by both host and pathogen to gain ascendency over one another. IRG targeting is only seen, for example, using less virulent type II and III forms of T. gondii because virulent type I strains have acquired mechanisms to interfere with IRG recruitment (Fentress et al., 2010; Fleckenstein et al., 2012; Niedelman et al., 2012; Steinfeldt et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2009a; Zhao et al., 2009b). Such interference relies on the combined action of two secreted rhoptry proteins, ROP5 and ROP18. The functional kinase ROP18 engages mouse Irga6 and Irgb6 via the pseudokinase ROP5 to maintain these IRGs in the non-active GDP-bound conformation (Fentress et al., 2010; Fleckenstein et al., 2012; Niedelman et al., 2012; Steinfeldt et al., 2010). ROP5 binding, in particular, exposes active site threonines on the GTPase switch I loop that are then targeted by ROP18 for phosphorylation and inactivation, which prevent Irga6 and Irgb6 targeting to the parasitophorous vacuole (Fentress et al., 2010; Fleckenstein et al., 2012; Niedelman et al., 2012; Steinfeldt et al., 2010). Thus pathogen strategies directed against IRG recruitment underscores its importance for cell-autonomous control in different vertebrate hosts.

Compartmental Signatures Recognized by IRGs

What are the compartmental signatures sensed by IRGs? To date, little is known about the molecular determinants of vacuolar recognition, although work with Mycobacterium bovis BCG found host phosphatidylinositide lipids (PtdIns3,4P2 and PtdIns3,4,5P3) generated by class I phosphatidylinositide kinases (PI3Ks) can act as a spatial cue for soliciting Irgm1 to the phagocytic cup within minutes of bacterial uptake (Figure 2). Irgm1 directly binds PtdIns3,4,5P3 and PtdIns3,4P2 via a C-terminal amphipathic helix (αK); mutation of this region or inhibition of class I PI3Ks impaired its targeting to plasma membrane-derived phagosomes in IFN-γ-activated macrophages (Tiwari et al., 2009) (Figure 2). Here lipid binding also served a second function, helping de-repress an intramolecular inhibition of the αK helix to facilitate GTP hydrolysis and transition state binding to its effector proteins once Irgm1 had reached the mycobacterial phagosome (Tiwari et al., 2009). Thus certain host lipid species not only act as a recognition motif but may also trigger an allosteric switch in Irgm1 to start assembling the pre-fusogenic machinery on the bacterial vacuole.

Evolution of a lipid sensing domain in the IRGs fits with other mammalian GTPases; inspection of 125 Ras, Rab, Arf and Rho GTPases, for example, found nearly a third contained C-terminal amphipathic helices which bound PtdIns3,4,5P3 and PtdIns4,5P2 for redirection to the plasma membrane (Heo et al., 2006). Because vacuolar pathogens like Salmonella typhimurium secrete phosphatases (SopB) which dephosphorylate these PtdIns in establishing their replicative niche (Hernandez et al., 2004), Irgm1 may be forced to recognize other lipid species or use different interaction domains besides the αK helix to target such bacteria as part of a co-evolutionary arms race (Kuiji and Neefjes, 2009). Consistent with this idea, Irgm1 also binds diphosphatidylinositol (DPG, or cardiolipin) which is a common inner membrane constituent of many gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria that is found on their phagosomes (Matsumoto et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2009).

Human IRGMd likewise binds DPG (Singh et al., 2010). Here the regions used to engage this phospholipid are different, however, as it lacks the Irgm1-related CTHD (Bekpen, 2005; 2009). IRGMd may instead enlist N-terminal helices or even acquire a lipid sensing domain in trans via its partners, since IFN-inducible GTPases interact with each other to regulate traffic to vacuolar compartments (Hunn et al., 2008; Khaminets et al., 2010; Traver et al., 2011; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). Whether other host or pathogen lipid species besides PtdIns3,4,5P3, PtdIns4,5P2 and DPG serve as intracellular PAMPs to recruit IRGs remains to be tested. So, too, does the possibility that specific lipids impose membrane curvature profiles which act as a second level of IRG recognition for sensing and discriminating between different pathogen compartments.

Consequences of IRG Recruitment

Once IRGs reach the pathogen vacuole, what are the consequences for cell-autonomous immunity? Studies of AIEC, Chlamydia, Mycobacteria, Salmonella and Toxoplasma have begun to shed light on this issue (Al-Zeer et al., 2009; Brest et al., 2011; Hunn et al., 2008; Khaminets et al., 2010; Lapaquette et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2008). IRGs serve distinct roles depending on which biochemical class - GKS or GMS - they belong. This functional classification developed by Hunn and co-workers (2008) is based on the presence of canonical (lysine, K) or non-canonical (methionine, M) G1 motifs (GxxxG[K/M]S/T) within the conserved N-terminal catalytic G-domain. Lysine substitution by methionine does not appear to adversely affect enzyme activity (Taylor et al., 1996; Tiwari et al., 2009) but nonetheless leads to divergent biological activities. IRGs of the GMS subclass (IRGMa-d in humans, Irgm1–3 in mice) appear to be intrinsic regulators, helping control the antimicrobial activities of their respective effectors, which include SNARE adaptor and autophagy proteins as well as GKS-containing IRGs and possibly even GBPs (Al-Zeer et al., 2009; Hunn et al., 2008; Khanimets et al., 2010; Lapaquette et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2009; Traver et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2008).

During infection with AIEC, Mycobacteria or Salmonella serovars, human IRGM and its murine Irgm1 ortholog recruit both autophagic (eg. MAP1/LC3) and SNARE adaptor (eg. Snapin) proteins to assemble fusogenic and possibly biogenesis of lysosome-related organelle complexes (BLOCs) in a pathogen-specific fashion for lysosomal targeting, since IFN-γ-induced autophagosome formation appears ostensibly normal in uninfected Irgm1−/− macrophages (Brest et al., 2011; Juarez et al., 2012; Gutierrez et al., 2004; Lapaquette et al., 2010; MacMicking et al., 2003; Matsuzawa et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2006, 2010; Tiwari et al., 2009; Traver et al., 2011). The human IRGM locus generates at least 5 mRNA transcripts encoding 4 IRGM isoforms: IRGMa-d (Bekpen et al., 2005; 2009). IRGMd is posited to translocate to mitochondria where it causes fission to elicit autophagy against mycobacterial infection (Singh et al., 2010), a process that could underlie autophagic responses to Salmonella typhimurium and AIEC as well (Brest et al., 2011; Lapaquette et al., 2010; McCarroll et al., 2008). Other human IRGM isoforms appear to target the M. tubeculosis phagosome directly when elicited through the innate immune receptor NOD2 by its ligand muramyl dipeptide in human alveolar macrophages (Juarez et al., 2012). Lastly, murine Irga6 binds the microtubule-binding protein Hook3 that is otherwise disabled by the Salmonella type III secretion effector, SpiC, to prevent phagolysosome fusion; whether this binding restores bacterial killing, however, has yet to be tested (Kaiser et al., 2004; Shotland et al., 2003). Several IRGs thus appear to act in concert to deliver phagocytosed bacteria via a number of interaction partners and pathways to lysosomes.

For Chlamydia serovars, mouse Irgm3 acts as a non-canonical guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) that releases membranolytic GKS-containing IRGs like Irga6 and Irgb10 to directly disrupt the Chlamydial inclusion body (Al-Zeer et al., 2009; Coers et al., 2008). Additionally, Irgm3 and Irga6 may intercept sphingomyelin-containing exocytic vesicles (Nelson et al., 2005) or bind to adipophilin/ADRP to regulate the trafficking of lipid bodies (Bougnères et al., 2009), which store neutral lipids and normally provide nutrition for the Chlamydial inclusion (Saka and Valdivia, 2012). Loss of these IRG activities renders Irgm3−/−, Irga6−/− and Irgb10−/− fibroblasts susceptible to infection with C. trachomatis or C. psittaci (Bernstein-Hanley et al., 2006; Coers et al., 2008; Miyairi et al., 2007).

The regulatory functions of IRGM proteins extend to Toxoplamsa gondii tachyzoites where a hierarchical model for interactions among IRGs themselves was first uncovered (Hunn et al., 2008). Here Irgms1–3 allow release and sequential accumulation of GKS IRGs - specifically, Irgb6, Irgb10, Irga6 and Irgd in that order - on the parasitophorous vacuole (Hunn et al., 2008; Khaminets et al., 2010). These functions are partly shared with the autophagy protein, ATG5, and members of the GBP family that facilitates IFN-γ or IFN-γ/LPS-induced Irga6 trafficking to the T. gondii vacuole in a non-canonical fashion (Khaminets et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2008). IRG targeting becomes detectable over a 10–20 minute period before progressive accumulation up to 90 minutes when the GTPase-driven oligomerization of different GKS IRGs leads to membrane vesiculation and disruption akin to the tubulating activities of other dynamin-like proteins (Ling et al., 2006; Martens et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2009a; Zhao et al., 2009b). This membrane disruption is reported to have different cell-autonomous fates depending on host cell type. In activated fibroblasts it leads to necroptosis (Zhao et al., 2009b) whereas in cytokine-stimulated macrophages the damaged parasite organelle appears to undergo autophagic elimination (Ling et al., 2006).

GMS-containing IRGs thus co-ordinate multiple classes of effectors – SNARE and BLOC adaptors, autophagy and lipid droplet proteins, GKS-containing IRGs and even GBPs – to promote cell-autonomous immunity to intracellular pathogens occupying different vacuolar habitats. Such widespread involvement likely contributes to the pronounced susceptibility phenotypes seen in several IRGM-deficient human and mouse hosts (see MacMicking, 2012).

GBPs Target Both Vacuolar and Cytosolic Pathogens

Patrolling the Host Cell’s Interior

Interactions within and outside the GBP family enable these 65–73kDa GTPases not only to patrol membrane-enclosed pathogens like Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycobacterium bovis and Toxoplasma gondii but also alert the innate immune system to cytosolically-escaped microbes as well. GBPs normally partition between the cytosol and endomembranes but upon infection are redirected to the pathogen compartment and to Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and a subpopulation of Salmonella typhimurium that have escaped their vacuole to replicate in the cytosol (DeGrandi et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Kravets et al., 2012; MacMicking, 2012; Tietzel et al., 2009).

GBP translocation requires nucleotide binding and catalytic activity to help self-assemble these larger GTPases along with their effector proteins (Kim et al., 2011; Kravets et al., 2012; MacMicking, 2012; Tietzel et al., 2009; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). Isoprenylation of human and mouse GBP1 and GBP2 is also required to recruit these two GTPases, for example, to M. bovis BCG, L. monocytogenes and S. typhimurium but not to T. gondii parasitophorous vacuoles (Kim et al., 2011; MacMicking, 2012; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). This selectivity is further evident for the kinetoplastid parasite Trypanosoma cruzii which fails to recruit mouse Gbp1 altogether in IFN-γ-activated macrophages (Virreira Winter et al., 2011). Such differential targeting probably reflects the membrane composition of distinct compartments inhabited by specific pathogens as well as the presence of host components on the bacterial envelope once they enter the cytosol (MacMicking, 2005; 2012). Again, targeting of GBPs to the site of pathogen replication often appears requisite for subsequent antimicrobial activity.

GBPs Assemble Pathogen-Specific Defense Complexes

What do the GBPs assemble on replicative vacuoles or deliver to cytosolic pathogens? Recent work indicates that different GBPs galvanize specific defense complexes that confer cell-autonomous resistance in both locations. Identification of these new GBP-mediated functions represent a major breakthrough for the field of host defense, since the molecular mechanisms employed by the atypical 65–73kDa GTPases had remained elusive for over two decades.

A family-wide screen combining three independent loss-of-function approaches – siRNA silencing, dominant-negative inhibition and chromosomal deletion – recently uncovered pathogen-specific involvement for four members against M. bovis BCG and L. monocytogenes (Kim et al., 2011). Here Gbp1, Gbp6, Gbp7 and Gbp10 promoted cell-autonomous defense in IFN-γ-activated macrophages while the generation of Gbp1-deficient mice revealed loss of bacterial control for these two pathogens in vivo (Kim et al., 2011).

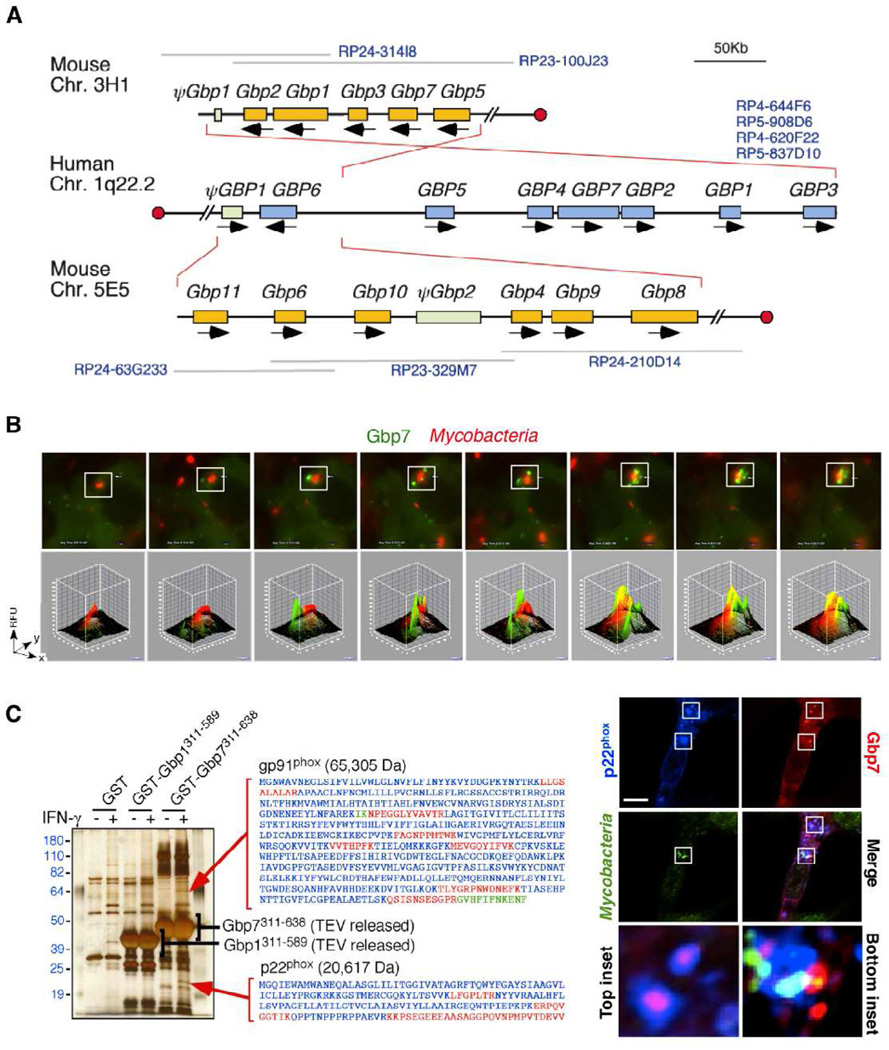

Subsequent studies have also reported susceptibility in mice with single deletions at the Gbp2 locus and en bloc deletion the entire Gbp cluster (Gbp2ps, Gbp2, Gbp1, Gbp3, Gbp7, Gbp5) on chromosome 3H1 (Gbpchr3) against T. gondii (Kravets et al., 2012; Yamamoto et al., 2012) (Figure 3). Despite lacking Gbp2, experiments in Gbpchr3 mice suggested Gbp1, Gbp5 and Gbp7 are more important based on reconstitution of individual Gbps in Gbpchr3 cells (Yamamoto et al., 2012). Likewise, susceptibility to L. monocytogenes in Gbp1−/− and Gbp5−/− mice was absent from Gbpchr3 animals that also lack both Gbps; here differences likely reflect the adminstrative route used, namely, oral versus peritoneal inoculation (Kim et al., 2011; Shenoy et al., 2012; Yamamoto et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the fact that Gbp1−/−, Gbp2−/− and Gbp5−/− single knockouts differ from Gbpchr3 mice against some of the same pathogens (T. gondii, L. monocytogenes) may indicate disrupted regulatory interactions among family members (Britzen-Laurent et al, 2010; Virreira Winter et al., 2011) or non-specific intergenic effects being associated with the 173kb deletion in Gbpchr3 mice (Yamamoto et al., 2012). Clean chromosomal deletions of each Gbp loci will thus probably be needed to correctly ascribe functions to individual members.

Figure 3. Members of the GBP Family Assemble Defense Complexes.

(A) Chromosomal configuration of human and mouse GBP families showing inverted and direct synteny of mouse chromosome 3H1 and 5E5 with human chromosome 1q22.1 (Kim et al., 2011). BAC clones spanning GBP clusters that were used for assembly are listed in blue font. Red circles designate centromeric orientation.

(B) Gbp7 (green) also targets M. bovis BCG (red) within 30 minutes as seen via live imaging in IFN-γ-activated mouse macrophages. Relative fluorescent units (RFU) for boxed insets shown below.

(C) (Left) Retrieval of endogenous NADPH oxidase membrane-spanning gp91phox and p22phox subunits by the Gbp7 C-terminal helical domain (CTHD) specifically from IFN-γ-activated macrophage lysates in silver-stained gels. Individual mass spectrometric peptides shown alongside in red, with overlapping peptides in green. (Right) Gbp7 (red) and p22phox (blue) on vesicles targeting M. bovis (green) in IFN-γ-activated macrophages (inset squares shown below). Scale bar, 10µm (Kim et al., 2011).

Protein-protein interaction screens found Gbp1 and Gbp7 assembled oxidative and autophagic complexes for bacterial elimination (Kim et al., 2011) (Figure 3). Gbp7 bound NADPH oxidase, a membrane complex that generates superoxide, and Atg4b, a cysteine protease required for autophagy, while Gbp1 engaged the ubiqutin-binding protein p62/Sequestosome-1. Gbp7 could help form the NADPH oxidase by acting as a bridging protein between the membrane-associated heterodimer, p22 phox-gp91phox, and cytosolic p67phox to assemble the superoxide (O2−)-generating holoenzyme on bacterial phagosomes. Gbp7 also recruits Atg4b to help drive the extension of autophagic membranes around bacteria within damaged compartments, an activity that is likely to require Gbp7 self-assembly. Atg4b was found to be recruited to T. gondii vacuoles, although this was not affected in Gbpchr3 peritoneal macrophages, similar to that seen for the oxidative burst (Kim et al., 2011; Yamamoto et al., 2012)., Such differences may arise from pathogen-specific responses for Gbp7 against Mycobacterium versus Toxoplasma, elicited versus resting cells, or the loss-of-function strategy employed (Dupont and Hunter, 2012). Gbp1 bound p62/Sequestosome-1 to help deliver ubiquitinylated cargo to autolysosomes and possibly respond to bacteria “marked” by ubiquitin in the cytosol where it solicits other GBPs as effectors (Kim et al., 2011; MacMicking, 2012).

This interdependence between GBP family members is similarly noted against T. gondii where Gbp1 can recruit Gbp2 and Gbp5 as downstream partners (Virreira Winter et al., 2011). A pan-Gbp1–5 antibody also retrieved endogenous Irgb6 suggesting certain GKS IRGs are recruited as potential membranolytic effectors (Yamamoto et al., 2012), although their absence from the human genome indicate that human GBPs probably operate via different mechanisms in IFN-γ-activated cells (Bekpen et al., 2005; Neidelman et al., 2012). Notably, virulent type I T. gondii strains strongly interfere with GBP recruitment, a process that enlists the parasite rhoptry proteins ROP16, ROP18 and the parasite dense granule protein, GRA15 (DeGrandi et al., 2007; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). Whether ROP16 and ROP18 kinases phosphorylate the analogous switch I region in GBPs to turn off this class of host defense GTPases akin to the IRGs awaits experimental validation.

Besides bacteria and protozoa, GBPs also promote cell-autonomous defense against viruses. This antimicrobial profile differs from the IRGs which apear to lack intrinsic antiviral activity but resembles the related IFN-inducible MX GTPases that are potent viral restriction factors, especially against orthomyxoviruses such as influenza A (Haller and Kochs, 2011). Human GBP1, GBP3 and a C-terminally truncated GBP3 splice isoform designated GBP3ΔC were recently found to inhibit influenza A in IFN-γ-activated lung epithelia as well (Nordmann et al., 2012). Antiviral activity required the G-domain and was dependent on GTP-binding but not hydrolysis, suggesting oligomerization was essential for repressing the influenza PB1, PB2 and PA polymerase complex that leads to reduced viral RNA and protein synthesis (Nordmann et al., 2012). Thus a recurring biochemical feature of this superfamily - self-assembly - appears important for the antimicrobial activity of many GBPs against at least three pathogen classes: bacteria, protozoa and viruses.

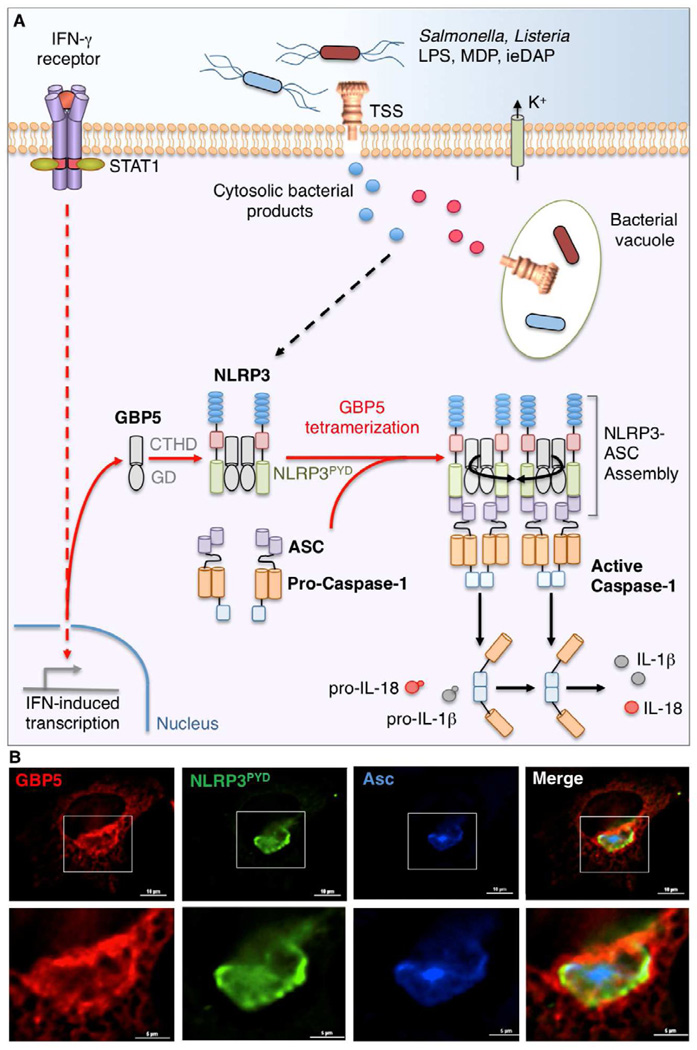

GBP5-Mediated Inflammasome Activation

Another recent discovery is the involvement of GBP5 in assembling the NLRP3 inflammasome, a complex that senses microbial molecules and stimulates caspase-1 activation and proinflammatory cytokine production. Interestingly, GBP5 mediated NLRP3 assembly specifically in response to infectious agents like bacteria and their cell-wall components but not to sterile agonists or adjuvants such as alum (Shenoy et al., 2012) (Figure 4). GBP5 is the first non-canonical protein to exhibit this activity, leading to a reappraisal of the way in which inflammasomes are regulated in immunologically-activated cells to combat infection (Caffrey and Fitzgerald, 2012).

Figure 4. GBP5 as an Inflammasome Activator During Cell-autonomous Host Defense.

(A) Schematic model of IFN-γ-induced GBP5 that helps assemble the NLRP3 inflammasome in response to whole bacteria, their TSS-secreted products and cell wall fragments (lipopolysaccharide [LPS], muramyl dipeptide [MDP] and γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid [ieDAP]) within the cytosol. These activating signals are accompanied by potassium efflux (K+) and mobilize tetrameric GBP5 bound via its G-domain (GD) to the pyrin domain of NLRP3 (NLRP3PYD) to begin assembling the inflammasome complex that includes the adaptor protein, Asc, which bridges NLRP3 and the zymogen, pro-caspase-1. This GBP5-dependent assembly ultimately leads to caspase-1 autoproteolysis and activation to cleave its pro-cytokine substrates, interleukin-1β and IL-18 (Shenoy et al., 2012; Caffrey and Fitzgerald, 2012).

(B) Formation of a GBP5 scaffold around the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome in response to LPS and K+ ionophore, nigericin, in human HeLa cells reconsituted with ASC (blue), GBP5 (red) and NLRP3PYD (green) (Shenoy et al., 2012). Scale bar, 10µm. Boxed insets shown below.

Evidence of this relationship came from large-scale in silico screens designed to mine interdomain similarities across 574 GBP-related sequences from 91 taxa: it retrieved NOD-like receptor (NLR) domains fused to ancestral GBPs from lower organisms (Shenoy et al., 2012). This suggested interactions between the GBPs and inflammasome-related NLRs could exist in higher species such as mammals, except here the relevant domains would be separated onto seemingly unrelated proteins through evolutionary divergence. Probing interdomian profiles of lower organisms thus enabled functional relationships to be established in higher species that would otherwise remain imperceptible because they operate over large protein distances.

Subsequent analysis found human GBP5 and its murine Gbp5 ortholog were critical for NLRP3 but not AIM2 or flagellin-dependent NLRC4 inflammasome activation in IFN-γ-activated macrophages and in Gbp5-deficient mice (Figure 4). The stimulus-dependent role of GBP5 encompassed live Salmonella and Listeria infection as well as their cell wall components (LPS, MDP), but not crystalline agents that also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome via a different pathway involving lysosomal rupture (Shenoy et al., 2012; Caffrey and Fitzgerald, 2012). How this selectivity is imposed remains unknown but it leads to NLRP3 assembly by GBP5 tetramerization as a bound partner to activate pro-caspase-1 (Shenoy et al., 2012) (Figure 4). Thus GBP5 represents a unique ligand-specific rheostat for NLRP3 activation that links earlier observations on its role during Salmonella typhimurium-induced pyroptosis to help restrict infection in a cell-autonomous manner (Rupper and Cardelli, 2008).

Atomic insights into Flu-Resisting Mx Proteins

IFN-inducible MX GTPases differ from the IRGs and GBPs in that they direct their antimicrobial activities almost exclusively to viruses. Originally identified as an inherited trait conferring resistance to influenza A as shown by susceptible mouse strains that harbor deletions or nonsense mutations in the murine Mx1 (Myxoma resistance gene 1) locus, the MX proteins are now established broad-spectrum antiviral proteins effective against flu and influenza-like togaviruses as well as bunyaviruses, rhabdoviruses, Thogoto, Coxsackie and Hepatitis B viruses (Haller and Kochs, 2011; MacMicking, 2012). Indeed, their importance is perhaps best exemplified by the ability of a human MX1 transgene to completely rescue mice lacking IFN type I (IFNα/β) receptors from influenza infection, indicating MX1 is sufficient to act autonomously without other type I IFN-induced restriction factors (see Haller and Kochs, 2011).

More recently, crystallographic analysis has begun to unveil the molecular mechanisms used by human MX1 at the atomic level (Gao et al., 2010; 2011). Nucleotide-free stuctures of this GTPase found three topographical domains: a globular N-terminal G-domain, an extended three helical bundle termed the central bundle signaling element (BSE), and a stalk spanning the middle and C-terminal GTPase effector domains (GED) responsible for tetrameric self-assembly. Co-operative functions between the BSE and GED promote oligomerization akin to the dynamin family and are essential for antiviral function (Gao et al., 2010; 2011). Hinges each side of the BSE enable MX1 mechanoenzyme movement that on the basis of minireplicon systems are likely to assemble oligomeric rings around viral nucleocapsid proteins bound by the MX1 stalk region to immobilize them (Haller and Kochs, 2011). An appealing feature of this structural model is that it accommodates the known ability of MX proteins to target different viruses independently of viral nucleotide or sequence composition.

Human Genetics of the IFN-inducible GTPases: Tuberculosis, Crohn’s and miRNAs

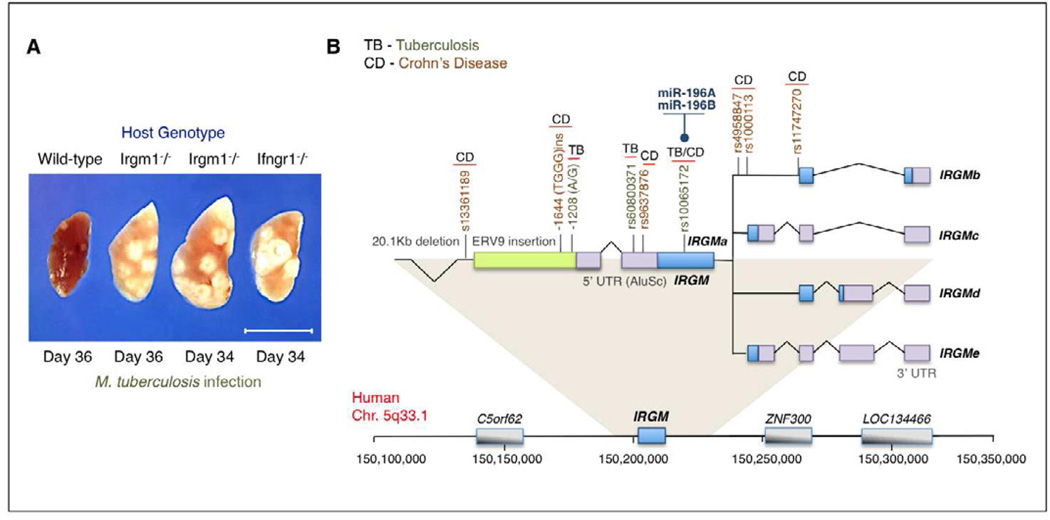

Recent human genetic studies implicate IRGM and several GBPs in the protective or inflammatory immune response to clinical tuberculosis (TB), findings consistent with the experimentally determined in vivo roles for Irgm1 and Gbp1 against M. tuberculosis and its close relative, M. bovis BCG (Kim et al., 2011; MacMicking et al., 2003) (Figure 5). Examination of IRGM variants in over 2,000 pulmonary TB patients and their unaffected controls found increased risk frequencies associated with the IRGM 2621TT genotype against M. tuberculosis but not M. africanum clades in a Ghanese population (Intemann et al., 2009). TB susceptibility in African Americans also segregates with single nucleotide IRGM polymorphisms (SNPs, rs13361189 T/C and rs10065172 C/T) that are in linkage disequilibrium with a 20kb upstream deletion (King et al., 2011), while a −1208 A/G allelic promoter polymorphism within this region match smear and/or culture-positive TB in Beijing cohorts (Che et al., 2010) (Figure 5). Hence alterations in the IRGM locus may yield candidate susceptibility profiles in diverse human populations against different mycobacterial species.

Figure 5. Disease-Associated Polymorphisms in the Human IRGM Locus.

(A) Early observations of pulmonary TB susceptibility in experimental animals harboring a chromosomal deletion of the Irgm1 locus following aerogenic infection with M. tuberculosis (MacMicking et al., 2003) are now emerging for the IRGM locus in the human population (see below). Wild-type and Ifngr1 (ligand-binding chain of the IFN-γ receptor)-deficient mice served as positive and negative controls, respectively, in these initial experiments. Scale bar, 1 cm.

(B) Configuration of the IRGM locus on human chromosome 5q33.1 that yields 5 splice mRNA isoforms (IRGMa-e) predicted to encode 4 different IRGM proteins (IRGMa, IRGMb, IRGMc/e, IRGMd) (Bekpen et al., 2005; 2009). Upstream ERV9 retroelement insertion plus Alu repeats shown together with the 20.1kb deletion polymorphism in linkage disequilibrium with a coding SNP rs10065172 that results in reduced IRGM expression and susceptibility to both TB and CD. Haplotypes at this nucleotide (313T/c) are selectively targeted by miRNA-196 to destabilize IRGM transcripts in intestinal epithelia and certain non-intestinal cell types (McCarroll et al., 2008; Brest et al., 2011). Other disease-associated polymorphisms and their respective SNPs across the IRGM locus are depicted.

For the GBPs, recent genome-wide transcriptional profiling found patients undergoing active TB mobilized strong modular signatures within neutrophils dominated by IFN-induced genes such as GBP1, GBP2 and GBP5 that are also prominent in the lungs of TB-infected animals (Berry et al., 2010; Marquis et al., 2011). Extrapolating from studies of Gbp1−/− and Gbp5−/− mice, such responses are likely to be protective overall, however, persistent inflammasome activation may lead to pulmonary damage (Kim et al., 2011; Shenoy et al., 2012). Whether distinct GBP mutations influence human TB susceptibility like IRGM in different ethnic groups or geographical locations has yet to be investigated.

Comprehensive GWAS analysis has also recently shown IRGM acts as a major predisposing locus for Crohn’s disease (CD) (Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium et al., 2007; 2010). Suprisingly, SNPs immediately flanking IRGM on chromosome 5q33.1 have the strongest replicating frequency and are associated with the upstream 20kb deletion (Parkes et al., 2007), a finding confirmed in multiple CD studies (Khor et al., 2011) (Figure 5). This structural deletion is in linkage disequilibrium with a coding SNP that affects IRGM expression. Nucleotide 313T coding haplotypes are “risk” alleles that largely abolish IRGM expression in colonic epithelia which coincides with autophagy defects against S. typhimurium or colitogenic AIEC, whereas the 313C “protective” halpotype generally exhibits higher IRGM levels and intact autophagy responses (McCarroll et al., 2008). IRGM thus appears necessary for cell-autonomous defense against enteropathogens although its expression is tightly controlled. Recently a specific microRNA, miR-196, was found to limit IRGM expression in intestinal epithelia by binding the “protective” 313C allele since unchecked IRGM expression can lead to dysregulated autophagic immunity against AIEC and induce apoptosis (Brest et al., 2011) (Figure 5). Hence epigenetic silencing points to a complex regulatory circuit for IRGM in CD pathogenesis.

Similarly complex roles emerge for the GBPs as well. For example, GBP1 localizes to gap junctions in polarized human intestinal epithelial cells to inhibit enteropathogenic E. coli-induced apoptosis (Mirpuri et al., 2010; Schnoor et al., 2009). A more recent report, however, suggests this GTPase can also block epithelial cell proliferation by interferring with β-catenin signaling (Capaldo et al., 2012). Definitive chromosomal deletions of the human GBP1 locus may help resolve some of these issues as they relate to host defense operating within the gastrointestinal mucosa.

Concluding Remarks

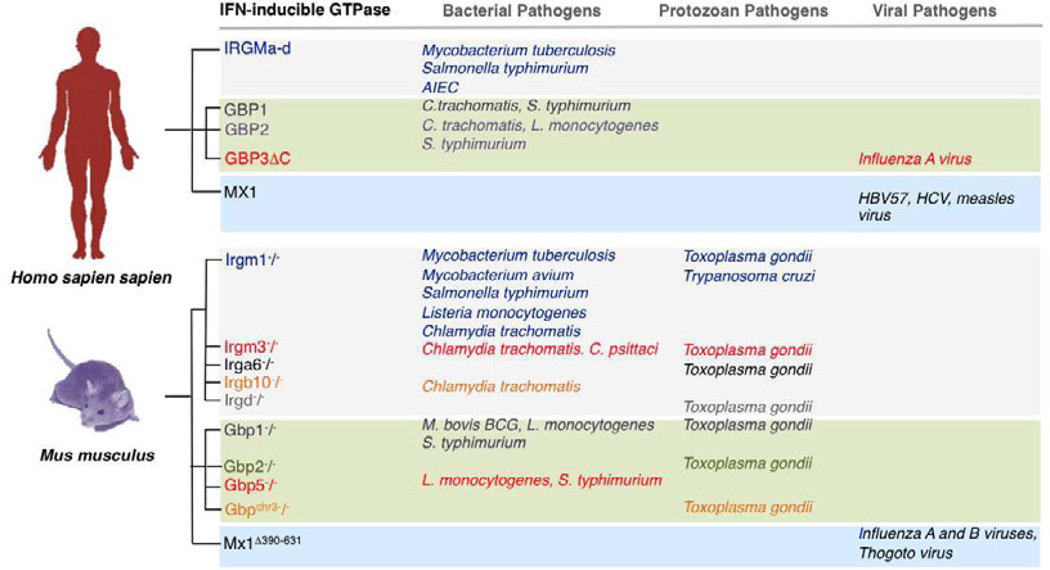

GTPases serve protean roles in every mammalian organ system, from synaptic vesicle trafficking to neutrophil chemotaxis to ion channel transport for glomerular filtration in the kidney (Colicelli et al., 2004). These and other physiological activities are subsumed by >180 GTPases in humans encompassing the RAS, RAC, RAB, RHO, ARF, dynamin and atlastin families (Colicelli, 2004). Emergence of an IFN-inducible GTPase superfamily with dedicated cell-autonomous defense functions adds another dimension to the sphere of biological reactions driven by guanine nucleotide binding and hydrolysis. That the IFN-inducible GTPases seem to have evolved highly pathogen-specific and subclass-dependent activities to defend the cell’s interior is a remarkable adaptation on the part of larger vertebrate hosts (Figure 6). Presumably such adaptations come with a fitness cost, however, since most immune GTPases are placed under strict transcriptional, epigenetic and post-translational control (MacMicking, 2012).

Figure 6. IFN-inducible GTPases Confer Pathogen-specific Host Defense.

Naturally occurring and genetically engineered loss-of-function mutations in humans and mice reveal patterns of pathogen-directed immunity among the IFN-inducible GTPase subgroups. IRG proteins appear heavily biased towards vacuolar bacteria and protozoa while MX proteins almost exclusively inhibit viruses. In contract, the GBPs are required for cell-autonomous resistance against all three pathogen classes. Abbreviations: HBV57, hepatitis B virus 57; HCV, hepatitis C virus; Mx1Δ390–631, congenital mouse Mx1 locus deletion encoding amino acids 390–631.

A number of outstanding questions remain regarding the biology of these new proteins, chief among them being the precise manner in which patterns of intracellular discrimination and defense are deployed. For example, what are the surface structures recognized by IRGs, GBPs, MX proteins and possibly GVINs on membrane compartments harboring different bacteria, protozoa and viruses? Similarly, how do IFN-inducible GBPs detect cytosolically escaped bacteria, and does detection uniformly leads to inflammasome activation or autophagic engulfment? What are the host effector pathways solicited by different GTPase family members to restrict microbial replication and, of equal importance, what are the pathogen-encoded tactics used to evade them? Recent evidence in Toxoplasma and Chlamydia as well as HCV, HIV-1 and Measles viruses point to multiple mechanisms for avoiding or manipulating the antimicrobial action of at least some IRGs and GBPs in their natural hosts (Fentress et al., 2010; Fleckenstein et al., 2012; Grégoire et al., 2011; Itsui et al., 2009; Niedelman et al., 2012; Steinfeldt et al., 2010; Virreira Winter et al., 2011). Future efforts should unearth others.

Lastly, the acquisition of such microbial strategies implies a strong selective pressure is placed by the IFN-inducible GTPases on intracellular pathogens irrespective of their replicative lifestyle. Harnessing that power for clinical benefit would represent a “first” in the field of cell-autonomous immunity and help answer the call for fresh approaches to anti-infective therapies (Nathan, 2012).

Acknowledgements

We apologize to colleagues whose work has not cited due to space limitations and acknowledge support for some of the discoveries described in this review from the following sources: Yale Brown-Coxe and Anna Fuller postdoctoral fellowships (A.R.S.); National Institutes of Health grant AI068041-06, Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award (1007845), Searle Foundation Scholars Program (05-F-114), Cancer Research Institute Investigator Award Program (CRI06-10), Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Senior Investigator Award (R09928), and W. W. Winchester Foundation (J.D.M.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HM, Braun PR, Zerrahn J, Meyer TF. IFN-γ-inducible Irga6 mediates host resistance against Chlamydia trachomatis via autophagy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekpen C, Hunn JP, Rohde C, Parvanova I, Guethlein L, Dunn DM, Glowalla E, Leptin M, Howard JC. The interferon-inducible p47 (IRG) GTPases in vertebrates: loss of the cell autonomous resistance mechanism in the human lineage. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R92. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-11-r92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekpen C, Marques-Bonet T, Alkan C, Antonacci F, Leogrande MB, Ventura M, Kidd JM, Siswara P, Howard JC, Eichler EE. Death and resurrection of the human IRGM gene. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein-Hanley I, Coers J, Balsara ZR, Taylor GA, Starnbach MN, Dietrich WF. The p47 GTPases Igtp and Irgb10 map to the Chlamydia trachomatis susceptibility locus Ctrq-3 and mediate cellular resistance in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14092–14097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603338103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MP, Graham CM, McNab FW, Xu Z, Bloch SA, Oni T, Wilkinson KA, Banchereau R, Skinner J, Wilkinson RJ, et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophildriven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–937. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Jiang Z, Georgel P, Crozat K, Croker B, Rutschmann S, Du X, Hoebe K. Genetic analysis of host resistance: Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity at large. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:353–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougnères L, Helft J, Tiwari S, Vargas P, Chang BH, Chan L, Campisi L, Lauvau G, Hugues S, Kumar P, et al. A role for lipid bodies in the cross-presentation of phagocytosed antigens by MHC class I in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brest P, Lapaquette P, Souidi M, Lebrigand K, Cesaro A, Vouret-Craviari V, Mari B, Barbry P, Mosnier JF, Hébuterne X, et al. A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xenophagy in Crohn's disease. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:242–245. doi: 10.1038/ng.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britzen-Laurent N, Bauer M, Berton V, Fischer N, Syguda A, Reipschläger S, Naschberger E, Herrmann C, Stürzl M. Intracellular trafficking of guanylate-binding proteins is regulated by heterodimerization in a hierarchical manner. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo CT, Beeman N, Hilgarth RS, Nava P, Louis NA, Naschberger E, Stürzl M, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. IFN-γ and TNF-α-induced GBP-1 inhibits epithelial cell proliferation through suppression of β-catenin/TCF signaling. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.41. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey DR, Fitzgerald KA. Immunology: Select inflammasome assembly. Science. 2012;336:420–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1222362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che N, Li S, Gao T, Zhang Z, Han Y, Zhang X, Sun Y, Liu Y, Sun Z, Zhang J, et al. Identification of a novel IRGM promoter single nucleotide polymorphism associated with tuberculosis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2010;411:1645–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coers J, Bernstein-Hanley I, Grotsky D, Parvanova I, Howard JC, Taylor GA, Dietrich WF, Starnbach MN. Chlamydia muridarum evades growth restriction by the IFN-γ-inducible host resistance factor Irgb10. J. Immunol. 2008;180:6237–6245. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colicelli J. Human RAS superfamily proteins and related GTPases. Sci STKE. 2004;250:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2502004re13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degrandi D, Konermann C, Beuter-Gunia C, Kresse A, Würthner J, Kurig S, Beer S, Pfeffer K. Extensive characterization of IFN-induced GTPases mGBP1 to mGBP10 involved in host defense. J. Immunol. 2007;179:7729–7740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont CD, Hunter CA. Guanylate binding proteins: Niche recruiters for antimicrobial effectors. Immunity. 2012;37:1919–193. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fentress SJ, Behnke MS, Dunay IR, Mashayekhi M, Rommereim LM, Fox BA, Bzik DJ, Taylor GA, Turk BE, Lichti CF, et al. Phosphorylation of immunity-related GTPases by a Toxoplasma gondii-secreted kinase promotes macrophage survival and virulence. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, De Camilli P. Dynamin, a membrane-remodelling GTPase. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:75–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein MC, Reese ML, Konen-Waisman S, Boothroyd JC, Howard JC, Steinfeldt T. A Toxoplasma gondii pseudokinase inhibits host IRG resistance proteins. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, von der Malsburg A, Paeschke S, Behlke J, Haller O, Kochs G, Daumke O. Structural basis of oligomerization in the stalk region of dynamin-like MxA. Nature. 2010;465:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature08972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, von der Malsburg A, Dick A, Faelber K, Schröder GF, Haller O, Kochs G, Daumke O. Structure of Myxovirus resistance protein a reveals intra- and intermolecular domain interactions required for the antiviral function. Immunity. 2011;35:514–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasper R, Meyer S, Gotthardt K, Sirajuddin M, Wittinghofer A. It takes two to tango: regulation of G proteins by dimerization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nrm2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Uthaiah R, Howard J, Herrmann C, Wolf E. Crystal structure of IIGP1: A paradigm for interferon-inducible p47 resistance GTPases. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire IP, Richetta C, Meyniel-Schicklin L, Borel S, Pradezynski F, Diaz O, Deloire A, Azocar O, Baguet J, Le Breton M, et al. IRGM Is a common target of RNA viruses that subvert the autophagy network. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002422. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller O, Kochs G. Human MxA protein: an interferon-induced dynamin-like GTPases with broad antiviral activity. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:79–87. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo WD, Inoue T, Park WS, Kim ML, Park BO, Wandless TJ, Meyer T. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez LD, Heuffer K, Wenk MR, Galan JE. Salmonella modulates vesicular traffic by altering phosphoinositide metabolism. Science. 2004;304:1805–1807. doi: 10.1126/science.1098188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunn JP, Koenen-Waisman S, Papic N, Schroeder N, Pawlowski N, Lange R, Kaiser F, Zerrahn J, Martens S, Howard JC. Regulatory interactions between IRG resistance GTPases in the cellular response to Toxoplasma gondii. EMBO. J. 2008;27:2495–2509. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intemann CD, Thye T, Niemann S, Browne EN, Amanua Chinbuah M, Enimil A, Gyapong J, Osei I, Owusu-Dabo E, Helm S, et al. Autophagy gene variant IRGM - 261T contributes to protection from tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis but not by M. africanum strains. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000577. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itsui Y, Sakamoto N, Kakinuma S, Nakagawa M, Sekine-Osajima Y, Tasaka-Fujita M, Nishimura-Sakurai Y, Suda G, Karakama Y, Mishima K, et al. Antiviral effects of the interferon-induced protein Guanylate Binding Protein 1 and its interaction with the hepatitis C virus NS5B protein. Hepatology. 2009;50:1727–1737. doi: 10.1002/hep.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez E, Carranza C, Hernández-Sánchez F, León-Contreras JC, Hernández-Pando R, Escobedo D, Torres M, Sada E. NOD2 enhances the innate response of alveolar macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in humans. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012;42:880–889. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser F, Kaufmann SH, Zerrahn J. IIGP, a member of the IFN inducible and microbial defense mediating 47 kDa GTPase family, interacts with the microtubule binding protein hook3. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1747–1756. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Könen-Waisman S, Zhao YO, Preukschat D, Coers J, Boyle JP, Ong YC, Boothroyd JC, Reichmann G, Howard JC. Coordinated loading of IRG resistance GTPases on to the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:939–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Shenoy AR, Kumar P, Das R, Tiwari S, MacMicking JD. A family of IFN-γ-inducible 65-kD GTPases protects against bacterial infection. Science. 2011;332:717–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KY, Lew JD, Ha NP, Lin JS, Ma X, Graviss EA, Goodell MA. Polymorphic allele of human IRGM1 is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis in African Americans. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamp T, Boehm U, Schenk D, Pfeffer K, Howard JC. A giant GTPase, very large inducible GTPase-1, is inducible by IFNs. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1255–1265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse A, Konermann C, DeGrandi D, Beuter-Gunia C, Wuerthner J, Pfeffer K, Beer S. Analyses of murine GBP clusters based on in silico, in vitro and in vivo studies. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravets E, Degrandi D, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Ries B, Konermann C, Felekyan S, Dargazanli JM, Praefcke GJ, Seidel CA, Schmitt L, et al. The GTPase activity of murine guanylate-binding protein 2 (mGBP2) controls the intracellular localization and recruitment to the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:27452–27466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.379636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiji C, Neefjes J. New insight into the everlasting host-pathogen arms race. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:808–809. doi: 10.1038/ni0809-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapaquette P, Glasser AL, Huett A, Xavier RJ, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive E. coli are selectively favoured by impaired autophagy to replicate intracellularly. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:99–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Zhang J, Sun Y, Wang H, Wang Y. The evolutionarily dynamic IFNinducible GTPase proteins play conserved immune functions in vertebrates and cephalochordates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:1619–1630. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Kaul S, Rounsley S, Shea TP, Benito MI, Town CD, Fujii CY, Mason T, Bowman CL, Barnstead M, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402:761–768. doi: 10.1038/45471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling YM, Shaw MH, Ayala C, Coppens I, Taylor GA, Ferguson DJP, Yap GS. Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2063–2071. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD. IFN-inducible GTPases and immunity to intracellular pathogens. Trends Immunol. 2004;11:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD. Immune control of phagosomal bacteria by p47 GTPases. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD. IFN-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:367–382. doi: 10.1038/nri3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD, Taylor GA, McKinney JD. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-γ-inducible LRG-47. Science. 2003;302:654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1088063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis JF, Kapoustina O, Langlais D, Ruddy R, Dufour CR, Kim BH, MacMicking JD, Giguère V, Gros P. Interferon regulatory factor 8 regulates pathways for antigen presentation in myeloid cells and during tuberculosis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S, Howard J. The interferon-inducible GTPases. Ann. Rev. Dev. Cell Biol. 2006;22:559–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S, Parvanova I, Zerrahn J, Griffiths G, Schell G, Reichmann G, Howard JC. Disruption of Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuoles by the mouse p47-resistance GTPases. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S, Sabel K, Lange R, Uthaiah R, Wolf E, Howard JC. Mechanisms regulating the positioning of mouse p47 resistance GTPases LRG-47 and IIGP1 on cellular membranes: retargeting to plasma membrane induced by phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2594–2606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Kusaka J, Nishibori A, Hara H. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa T, Kim BH, Shenoy AR, Kamitani S, Miyake M, MacMicking JD. IFN-γ elicits macrophage autophagy via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2012;89:813–818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll SA, Huett A, Kuballa P, Chilewski SD, Landry A, Goyette P, Zody MC, Hall JL, Brant SR, Cho JH, et al. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn's disease. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1107–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyairi I, Tatireddigari VR, Mahdi OS, Rose LA, Belland RJ, Lu L, Williams RW, Byrne GI. The p47 GTPases Iigp2 and Irgb10 regulate innate immunity and inflammation to murine Chlamydia psittaci infection. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1814–1824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirpuri J, Brazil JC, Berardinelli AJ, Nasr TR, Cooper K, Schnoor M, Lin PW, Parkos CA, Louis NA. Commensal Escherichia coli reduces epithelial apoptosis through IFN-alphaA-mediated induction of Guanylate Binding Protein-1 in human and murine models of developing intestine. J. Immunol. 2010;184:7186–7195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modiano N, Lu YE, Cresswell P. Golgi targeting of human guanylate-binding protein-1 requires nucleotide binding, isoprenylation, and an IFN-γ-inducible cofactor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8680–8655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503227102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Fresh approaches to anti-infective therapies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003081. 140sr2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Virok DP, Wood H, Roshick C, Johnson RM, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, Steele-Mortimer O, Kari L, McClarty G, et al. Chlamydial IFN-γ immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;101:10658–10663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504198102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedelman W, Gold DA, Rosowski EE, Sprokholt JK, Lim D, Arenas AF, Melo MB, Spooner E, Yaffe MB, Saeij JPJ. The rhoptry proteins ROP18 and ROP5 mediate Toxoplasma gondii evasion of the murine, but not the human, interferon-gamma response. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002784. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann A, Wixler L, Boergeling Y, Wixler V, Ludwig S. A new splice variant of the human Guanylate-Binding Protein 3 mediates anti-influenza activity through inhibition of viral transcription and replication. FASEB. J. 2012;26:1290–1300. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-189886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Grey J, Vestal DJ. In silico analysis of the human and murine guanylate-binding protein (GBP) gene clusters. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:328–352. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papic N, Hunn JP, Pawlowski N, Zerrahn J, Howard JC. Inactive and active states of the interferon-inducible resistance GTPase, Irga6, in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:32143–32151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804846200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, Fisher SA, Roberts RG, Nimmo ER, Cummings FR, Soars D, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:830–832. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash B, Praefcke GJK, Renault L, Wittinghofer A, Herrmann C. Structure of human guanylate-binding protein 1 representing a unique class of GTP-binding proteins. Nature. 2000;403:567–571. doi: 10.1038/35000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald PC, Beutler B. Plant and animal sensors of conserved microbial signatures. Science. 2010;330:1061–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.1189468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupper AC, Cardelli JA. Induction of Guanylate Binding Protein 5 by gamma interferon increases susceptibility to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium-induced pyroptosis in RAW 264.7 cells. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:2304–2315. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01437-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Schaffner SF, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Varilly P, Shamovsky O, Palma A, Mikkelsen TS, Altshuler D, Lander ES. Positive natural selection in the human lineage. Science. 2006;312:1614–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.1124309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka HA, Valdivia R. Emerging roles for lipid droplets in immunity and hostpathogen interactions. Ann. Rev. Dev. Cell Biol. 2012;28:4.1–4.27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoor M, Betanzos A, Weber DA, Parkos CA. Guanylate-binding protein-1 is expressed at tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells in response to interferon-gamma and regulates barrier function through effects on apoptosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:33–42. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Kim BH, Choi HP, Matsuzawa T, Tiwari S, MacMicking JD. Emerging themes in IFN-γ-induced macrophage immunity by the p47 and p65 GTPase families. Immunobiology. 2008;212:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Wellington DR, Kumar P, Kassa H, Booth CJ, Cresswell P, MacMicking JD. GBP5 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and immunity in mammals. Science. 2012;336:481–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1217141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotland Y, Kramer H, Groisman EA. The Salmonella SpiC protein targets the mammalian Hook3 protein function to alter cellular trafficking. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:1565–1576. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SB, Davis AS, Taylor GA, Deretic V. Human IRGM induces autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria. Science. 2006;313:1438–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SB, Ornatowski W, Vergne I, Naylor J, Delgado M, Roberts E, Ponpuak M, Master S, Pilli M, White E, et al. Human IRGM regulates autophagy and cellautonomous immunity functions through mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:1154–1165. doi: 10.1038/ncb2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeldt T, Konen-Waisman S, Tong L, Pawlowski N, Lamkemeyer T, Sibley LD, Hunn JP, Howard JC. Phosphorylation of mouse Immunity-Related GTPase (IRG) resistance proteins is an evasion strategy for virulent Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GA, Jeffers M, Largaespada DA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Woude GF. Identification of a novel GTPase, the inducibly expressed GTPase, that accumulates in response to interferon γ. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20399–20405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GA, Feng CG, Sher A. p47 GTPases: Regulators of immunity to intracellular pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:100–109. doi: 10.1038/nri1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietzel I, El-Haibi C, Carabeo RA. Human Guanylate Binding Proteins potentiate the anti-chlamydia effects of interferon-γ. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Choi HP, Matsuzawa T, Pypaert M, MacMicking JD. Targeting of the GTPase Irgm1 to the phagosomal membrane via PtdIns(3,4)P(2) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P(3) promotes immunity to mycobacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:907–917. doi: 10.1038/ni.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver MK, Henry SC, Cantillana V, Oliver T, Hunn JP, Howard JC, Beer S, Pfeffer K, Coers J, Taylor GA. Immunity-related GTPase M (IRGM) proteins influence the localization of guanylate-binding protein 2 (GBP2) by modulating macroautophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:30471–30480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripal P, Bauer M, Naschberger E, Mörtinger T, Hohenadl C, Cornali E, Thurau M, Stürzl M. Unique features of different members of the human guanylate-binding protein family. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:44–52. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaiah RC, Praefcke GJ, Howard JC, Herrmann C. IIGP1, an interferon-gamma-inducible 47-kDa GTPase of the mouse, showing cooperative enzymatic activity and GTP-dependent multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:29336–29343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virreira Winter S, Niedelman W, Jensen KD, Rosowski EE, Julien L, Spooner E, Caradonna K, Burleigh BA, Saeij JP, Ploegh HL, et al. Determinants of GBP recruitment to Toxoplasma gondii vacuoles and the parasitic factors that control it. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium et al. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium et al. Genome-wide association study of CNVs in 16,000 cases of eight common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2010;464:713–720. doi: 10.1038/nature08979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner M, Herrmann C. Biochemical properties of the human guanylate binding protein 5 and a tumor-specific truncated variant. FEBS. J. 2010;277:1597–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Okuyama M, Ma JS, Kimura T, Kamiyama N, Saiga H, Ohshima J, Sasai M, Kayama H, Okamoto T, et al. A Cluster of interferon-γ-Inducible p65 GTPases plays a critical role in host defense against Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2012;37:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Chen ZJ. Intrinsic antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:214–222. doi: 10.1038/ni.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, Miller BC, Cadwell K, Delgado MA, Ponpuak M, Green KG, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Ferguson DJ, Wilson DC, Howard JC, Sibley LD, Yap GS. Virulent Toxoplasma gondii evade immunity-related GTPase-mediated parasite vacuole disruption within primed macrophages. J. Immunol. 2009a;182:3775–3781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YO, Khaminets A, Hunn JP, Howard JC. Disruption of the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole by IFN gamma-inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) triggers necrotic cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2009b;5:e1000288. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]