Abstract

In the framework of an artistic–scientific project on eye-movements during reading, my collaborators from the psychology department at the KU Leuven and I had a close look at the poem “Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard” (“A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”) by Stéphane Mallarmé. The poem is an intriguing example of nonlinear writing, of a typographic game with white and space, and of an interweaving of different reading lines. These specific features evoke multiple reading methods. The animation, Movement in Un coup de dés, created during the still-ongoing collaboration interweaves a horizontal and a vertical reading method, two spontaneous ways of reading that point at the poem's intriguing ambiguity. Not only are we interested in different methods of reading; the scientific representations of eye movements themselves are a rich source of images with much artistic potential. We explore eye movements as “eye drawings” in new images characterized both by a scientific and by an artistic perspective.

Keywords: Un coup de dés, reading, nonlinear, eye movements, eye drawings, image, word, art and science

1. Introduction

The animation Movement in Un coup de dés (Figure 1) and this text are a first phase in, and a reflection on, a collaboration with Johan Wagemans and Frouke Hermens, two scientists from the Laboratory of Experimental Psychology at the University of Leuven. I gave the project the name “Reading paths, eye drawings and word islands.” The first results of the project that I describe were part of the exhibition “Over de eenheid en veelheid van het boek” (“On the unity and multiplicity of the book”) in the Nottebohm Room of the Library Hendrik Conscience in Antwerp (6 August to 11 September 2011). I had already worked with Johan Wagemans for several years in the framework of “Parallellepipeda,” a cross-over project between art and science with a final exhibition in the museum M in Leuven (28 January to 25 April 2010). You can read more about this collaboration in the text “Towards a new kind of experimental psycho-aesthetics? Reflections on the Parallellepipeda project” (Wagemans 2011). During this cooperation I became acquainted with recordings and reproductions of eye movements while looking at art. At that time, I was in the midst of preparing my PhD in the Arts, working on “Dimensions of the book.” At http://www.ruthloos.be, one can find a cluster of words summarizing what my PhD is about and many images.

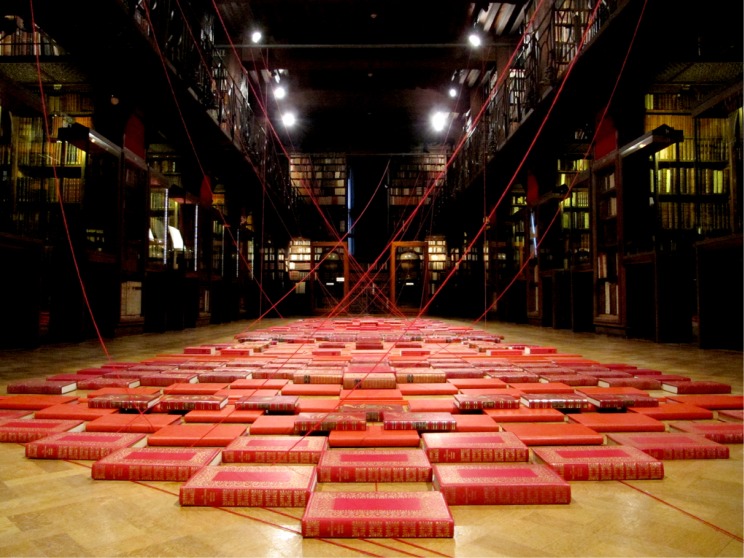

Figure 1.

Animation Movement in Un coup de dés shown at the solo exhibition “On the unity and multiplicity of the book” (2011) in one of Belgium's finest library rooms: the Nottebohm Room. The figure shows the installation Carpet of Books with Lines of Flight.

I became very curious about the way we read, seen from a scientific point of view. The authors that I have studied for my thesis provide philosophical and literary concepts that can be employed when contemplating the book, its relationship with the reader, the author, the world, and other books. They also speak about reading and writing, reading as branches in the imagination, reading as a creative act, and reading as rewriting. I wondered how reading is looked at by scientists (literally and figuratively) and whether this could enrich my intellectual and artistic quest around the book. In an early phase of this project, I understood that “an ordinary text” has a repetitive linear reading pattern (Rayner and Pollatsek 1989).

The representations of the scan paths reminded me of a kind of writing, an illegible one, an asemic writing that presents the visual aspects of language, and language as image. The very repetitive character (following the linear structure of the text) brought me to the question of what patterns would occur whilst reading texts with a different layout. We carried out experiments with a short text that had some specific features in its layout, as an opportunity to learn about a whole range of representation possibilities for the collected eye-movement data. Frouke Hermens, specialised in the field of visual perception, guided me through the world of vision sciences. She is currently preparing an article, based on these initial data, “Task effects on eye movements of viewers of nonlinear text” (Hermens no date), and recently started a study on the eye movements of linear and nonlinear poems of the Belgian poet Paul Van Ostaijen.

2. Movement in space and time, and in meaning

My interest in the work of the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–98) has focused on his life project “Le Livre” (“The Book”). In Mallarmé (1986) and Scherer (1978), one can read how he especially thinks about the structure of the book and how it should be a book that is characterized by movement, with mobile pages in different combinations allowing for different readings. An intriguing quote by Mallarmé reveals a special complexity: “A book neither begins nor ends: at most it pretends to” (cited from Scherer 1978, page 24). Mallarmé would never realize his total book. Although someone like Deleuze (1988, page 44) sees this differently: “Our error is in believing that they [Leibniz and Mallarmé] did not succeed in their wishes: they made this unique Book perfectly, the book of monads, in letters and little circumstantial pieces that could sustain as many dispersions as combinations.”

The element of movement and the possibility of different readings also play a role in Mallarmé's (1897/1914) last poem “Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard. Poème.” There is movement between the double pages with each showing other (textual) images, movement of the different reading lines that vary in size, and the typographic approach in which movement is expressed, not just in the size of the letters alone but also in the shape of the text. There is cyclic movement. The title of the poem is divided into quarters spread on the different pages. The poem ends with the same words with which it begins: “Un coup de dés.” There is movement in time, the reading process, movement in the individual readings of the same reader that vary, or of different readers, movement in more (or less) understanding, in grasping a meaning, in the appearing, disappearing, and reappearing of meaning.

3. Between text and image

“Un coup de dés” is a particularly difficult poem. In its hermetic form, it is very difficult to grasp. It is therefore not a narrative poem; rather it presents “prismatic subdivisions of an Idea” that appear in variable positions, as Mallarmé mentions in his foreword. “Un coup de dés” not only challenges our understanding but also alludes to another reading, a tabular reading. Here, it seems useful to make a link to the distinction made by Jean Gérard Lapacherie (1984) between a linear and analytical reading (word) and a tabular and synthetic reading (image).

The two poles—image and language—refer to reading and looking, a semiotics of the language and a semiotics of the image. They (the two poles) refer to a linear reading, a movement from left to right and from top to bottom, and a tabular reading: in all directions, there is no before and after, and no beginning and end, but a contiguity of characters.

Mallarmé comes close to a tabular reading through his specific dealing with the white, the tension between black and white, and the structure of the poem (see Figure 2 for an illustration). Blanchot (1959/2003, page 240) mentions in “The book to come” about “Un coup de dés” as oscillating between “visible” and “readable,” and about how the poem “tries to enrich analytical reading by global and simultaneous vision, and also to enrich static vision by the dynamism of the play of optical movements.”

Figure 2.

Double page 4 of the 11-page-long French poem.

The Belgian conceptual artist, Marcel Broodthaers (1925–76), plays in a special way with the image character of “Un coup de dés.” In his artist's book Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard. Image (Broodthaers 1969) (“Image” appears instead of “Poem”), the words of Mallarmé are replaced by black bars with the same dimensions (see Figure 3). The poem by Mallarmé, floating between word and image, becomes all image. However, the image here retains a strong bond with the word, because the image is not only image in a synthetic sense but just as much a text (albeit an illegible one), a geometric writing. The asemic writing is here, however, not something that refers to writing as such, but is something that refers to a very specific readable text, and that constitutes its particularity. Johanna Drucker (1995, pages 115–116) writes in The Century of Artists’ Books that Broodthaers, with his subtle approach to the work of Mallarmé, provides a conceptual analysis of the poem. Johan Pas (2010), also a connoisseur of artists’ books, writes that “Broodthaers’ ‘constellation’ parasitizes, parodies, and permutes. By reproducing the original layout of the experimental poem and transforming it into a geometric composition, Broodthaers linked the roots of the poetic avant-garde (“Un coup de dés” is considered to be the very first example of visual poetry) to those of the pictorial abstraction.”

Figure 3.

On the foreground one sees Broodthaers’ artists book printed on transparent paper. This transparency makes visible the underlying pages and provides as such a kind of summary of the book.

4. Eye movements or eye drawings?

“Un coup de dés” as nonlinear text and innovative typography makes one very curious about the form of concrete reading patterns. To be able to register and research eye movements, we worked with a digitized version of the poem. From each double page, we took a photograph. The two-page spread for Mallarmé is an important unit, including the centerfold. The photographs were presented on a 21-inch computer screen. Reading in the lab means that you do not turn a page but determine the pace at which the various pages are shown. It was not possible to go back or forward one or more pages, thus making the reading process more linear than usual. This gives the subjective feeling that you have less time to spend on each page than in a normal reading situation. However, the visual structure of the poem and its hermetic character is so special that it puts these restrictions of an unusual reading situation into the background.

Mallarmé wrote an interesting preface to the poem in which he reflects on different forms of reading, the impact of the typography, and the significant presence of the white. Certain representations of the eye movements make one think of constellations, and that is something that Mallarmé himself seems to suggest. Every double page “eye drawings” occurred (ie, what I as an artist could call (eye) drawings). Some of them had a similar visual structure to that of the text of the poem. These images, with small dots and lines, give the impression that the reader was looking for an image that connects points. This reinforces the idea of the poem as a “starry sky” (wherein we also perceive figures), an idea also mentioned by Van Dijk (2005, page 45). These scientific images of scan-paths that I isolate here underline the tabular or synthetic aspects of the poem (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Double page 7, scan path with fixations and saccades.

Figure 5.

Double page 9, scan path with fixations and saccades.

5. Horizontal and vertical movement

What drew our attention concerning two separate series of readings by one and the same reader were the differences in reading direction. In one case, it was a horizontal movement that passes the fold, and in another case, it was a vertical reading (that contained horizontal components) with a gaze that went downwards per single page. In both cases, this was a spontaneous reading movement.

For the animation shown in the exhibition “On the unity and multiplicity of the book,” these two ways of reading were interwoven. The animation presents the various reading methods evoked by the poem itself and which form a source of ambiguity.

In the viewer function of our analysis program, the horizontal reading, an edited scan-path, could be inserted as a background. The text of the poem was omitted, texture was brought in, and the colours were changed to red and white. The shape of the eye drawing (the scan-path) itself, in linear white, remained unchanged (Figure 6). Over this static image, a second dynamic reading was laid. In the animation (http://www.youtube.com/user/EyeDrawings) a blue dot can be seen moving over the white linear drawing forming a rather vertical route per page. Also in blue, there is a timer that indicates the passing of time.

Figure 6.

Basis image (“found and created”) for the animation.

That the poem evokes multiple reading methods is also confirmed by Van Dijk (2005, page 47). She refers to Malcolm Bowie, who makes a connecting idea in Mallarmé and the Art of Being Difficult. Bowie speaks about concurrent reading methods. Text fragments, isolated by space, become available in a new way. Semantic strings are formed across syntactic boundaries, by the grace of the white. Bowie speaks in terms of a “network of rebellious structures” and “the multifarious semantic texture of Mallarmé's lay-out” (Bowie 1978, page 123).

Before the creation of this animation, a prior idea was to work only with a moving red dot on a white background in an animation that included the overall reading of the 11 double pages of the poem. I imagined it as an independent mural work. However, during the project this idea changed, because I wanted to make a work that could connect with the specific architecture and characteristic display possibilities in the Nottebohm Room (Figure 7). In addition, this specific environment was an opportunity to exhibit the two original books (of Mallarmé and of Broodthaers). As it is possible to open them on one double page only (in a physical constellation, not a digital rendering), I decided to focus on one double page for the three works, in this case, page 4.

Figure 7.

Setup in the Nottebohm Room with, on the left, the book by Mallarmé and, on the right, the book by Broodthaers. The animation was displayed in between. The white scan-path has a similar visual structure as is seen in the open book pages. The path that is followed by the blue dot is differing.

6. Further possibilities

In further development of this project, it could be interesting to present two readings side by side, a reading of the book of Mallarmé and a “reading” of the book by Broodthaers; or to gather various readings of one reader of the work of Mallarmé to see how the reading changes as one gradually understands more of the poem. Reading and rereading. Reading as rereading. Vladimir Nabokov argued that one cannot read a book, only reread it. A good, creative reader is a rereader. A similar idea is developed by Roland Barthes: rereading a text makes a text multiple (Chupin 2002).

We could also collect many readings of many readers, as a kind of intertextual summary, or summarize the work itself in a layered reading, as Broodthaers seems to do in the beautiful edition on translucent paper.

Would it be possible during our study to learn something about “meaning” and where it occurs, or about our thoughts, and their forms? For example: which kind of eye drawings would arise if we read Paul Van Ostaijen's (2010, page 123) poem that opens upper left with “the bar is empty” and closes bottom right with “and full of people,” separated by a sea of white? What drawings would occur in this sea, and could these drawings tell us something about our imagination? Aside from this (unrealistic) question, we could ask ourselves: What can we learn from reading poetry, about reading in a general sense?

Another project within this project could be to examine the effect on the reading pattern caused by reading with tasks. Working with tasks builds further on studies which examined what eye movements observers make when they look at a work of art, like Yarbus (1965/1967), who made an observer look at a painting while he tried to answer different questions about the painting. In the context of reading a normal linear text, or an otherwise designed text, a reader could be asked to pay attention to specific words that reappear, to the use of different languages, to different reading directions, and to the spacing of the text columns. As I learned from Frouke Hermens, who has been analysing the data on participants who read a text according specific tasks, these tasks lead to interesting and varying scan-paths.

Returning to Mallarmé, looking at the scientific material was an inspiring way to get to know the poem in some of its multiplicity and, thereby, to learn something about reading as a physical act, which is never separated from reading as a mental act. How do scientific representations (from my artistic point of view: how do eye drawings) hover between optical perception and subjective imagination?

In addition to an intellectual motivation, there is the artistic curiosity. The many different representation methods of eye movements are a real artistic potential to examine. There are several possible ways to continue our project.

One of such is the creation of a series of animations in which qualities of specific representations can be highlighted. The new moving images can acquire (a certain degree of) autonomy compared with their origin. There are possible departures such as putting a reading of Mallarmé's Poem over Broodthaers’ Image, or vice versa; presenting multiple readings of the same two-page spread together in one and the same image, as a moving tangle; or not presenting eye drawings as a static image but letting them originate in an animation—the eye that draws its trajectory in real time.

We were reminded of the importance of the white in the poem of Mallarmé by mistakenly placing the eye movements of a previous page over a following page, which meant that the eye was reading the white only, and not the text, thus causing a humorous effect. This could also be a starting point for a new creation.

The intention is not to stay close to the scientific material during the whole project but to create an independent work, enriched by the sciences. One example is the intertwining of two images into one independent image: the asemic writing and the eye drawing—or how reading and writing have something in common.

7. In between

The special feature of this collaboration is the active participation of both sides, leading to new creations that—for now—seem to exist in an intermediate space. The animation, in its partly unfamiliar use of eye-movement data, is still clearly recognizable by the scientist, but not necessarily by the nonprofessional, including the artist and spectator, for example. At the same time, the (“partly created, partly found”) animation became semi-independent in an artistic way, as it was shown in an exhibition context, in a context of visual arts. This allows aspects other than scientific aspects to appear. However, I would not call the animation an artwork. It is a work that bridges two worlds, art and science. In fact, the visual beauty in science itself makes bridging possible. The specific aesthetics, real and potential, of graphical (static and dynamic) representations, and the way they connect to the imagination of the viewer, overcome the gap between arts and sciences.

Acknowledgments

Johan Wagemans and Frouke Hermens were the other beautiful “aspects,” ie persons who made the bridging possible. I would also like to thank Dorothee Augustin for her important support.

Biography

Ruth Loos has a masters in Fine Arts and Art Studies. She is currently working on a PhD in the Arts (‘Dimensions of the book ‘) at the Associated Faculty of Architecture and the Arts / the K.U.Leuven Association. In her research she reflects on the limits of the book, the inside and outside, the oneness and multiplicity of the bookthe book that transgresses itself in a paradoxical way. She exhibits regularly and gives seminars and lectures in the framework of her research. She teaches at the Hogeschool Sint-Lucas Beeldende Kunst Ghent (Visual Arts). She also writes about art projects, exhibitions, and the work of individual artists. See also http://www.ruthloos.be.

Ruth Loos has a masters in Fine Arts and Art Studies. She is currently working on a PhD in the Arts (‘Dimensions of the book ‘) at the Associated Faculty of Architecture and the Arts / the K.U.Leuven Association. In her research she reflects on the limits of the book, the inside and outside, the oneness and multiplicity of the bookthe book that transgresses itself in a paradoxical way. She exhibits regularly and gives seminars and lectures in the framework of her research. She teaches at the Hogeschool Sint-Lucas Beeldende Kunst Ghent (Visual Arts). She also writes about art projects, exhibitions, and the work of individual artists. See also http://www.ruthloos.be.

References

- Blanchot M. In: Le livre à venir [The Book to Come] Mandell C, editor. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1959/2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie M. Mallarmé and the Art of Being Difficult. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Broodthaers M. Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard. Image [A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance. Image] Antwerpen: Drukkerij Altypo; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chupin Y. The Poetics of Re-reading in Nabokov's Pale Fire and Barthes’ S/Z. 2002. Postgraduate English Journal, Durham University, 8 September http://www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english/chupin.htm#first.

- Deleuze G. Le Pli: Leibniz et le Baroque [The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque] Paris: Les Editions de Minuit; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker J. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York, NY: Granary Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hermens F. Task effects on eye movements of viewers of non-linear text. no date.

- Lapacherie J G. De la grammatextualité. [On grammatextuality] Poétique. 1984;59:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Mallarmé S. Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard. Poème [A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance. Poem] Paris: Gallimard; 1897/1914. [Google Scholar]

- Mallarmé S. Stéphane Mallarmé. Écrits sur le livre. Choix de textes [Stéphane Mallarmé. Writings on The Book. Choice of Texts] Alençon: Éditions de l’Éclat/Editions Gallimard; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pas J. Artists’ Books (Gent: Rektoverso) 2010. 40 March-April 2010 http://www.rektoverso.be/artikel/kunstenaarsboeken.

- Rayner K. Pollatsek P. The Psychology of Reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer J. Le “livre” Mallarmé [The “Book” Mallarmé] Mayenne: Editions Gallimard; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk Y. Leegte die ademt. Het typografisch wit in de moderne poëzie. [Typographical blanks in modern poetry] Academisch proefschrift, Universiteit van Amsterdam; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ostaijen P. Bezette stad: Nagelaten gedichten [Occupied City: Poems] Amsterdam: Atheneum-Polak en Van Gennep; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wagemans J. Towards a new kind of experimental psycho-aesthetics? Reflections on the Parallellepipeda project. i-Perception. 2011;2:648–678. doi: 10.1068/i0464aap. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbus A L. In: Eye Movements and Vision. Haigh B, editor. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1965/1967. [Google Scholar]