Abstract

Background

Bright-light treatment is a safe and effective treatment for the management of winter seasonal affective disorder (SAD). In a recent study, we found that the relative duration of reading was positively associated with likelihood of remission after six weeks of light treatment.

Methods

Two technicians measured the illuminance of a light box with a light meter directed towards the center of reading material that was placed on a table in front of the light box. The measurement was also performed after reading material was removed. The two measurements were performed in a randomized order. Friedman analysis of variance with Wilcoxon post-hoc tests were used to compare illuminance with vs. without reading.

Results

The presence of the reading material increased illuminance by 470.93 lux (95% CI 300.10–641.75), p<0.0001.

Limitations

This is a technical report done under conditions intended to mimic those of typical ambulatory light treatment as much as possible.

Conclusions

As reading materials reflect light from the light box, reading during light therapy increases ocular illuminance. If confirmed by future studies using continuous recordings in randomized design, instructing SAD patients to read during light therapy may contribute to a more complete response to light treatment. The downside of specific relevance for students, is that reading, in particular, with bright light in the late evening/early night may induce or worsen circadian phase delay, adversely affecting health and functioning.

Keywords: Illuminance, light treatment, phototherapy, seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

Introduction

Seasonal affective disorder, (SAD), winter type, is a debilitating condition consisting of recurring major depressive episodes during fall and winter with full remission during spring and summer (1, 2). Patients with SAD show changes in retinal function that are restored by 4 weeks of light treatment. These changes include electroretinogram (ERG) changes in the winter, when compared with healthy individuals, with lower cone maximal amplitude and lower rod retinal sensitivity (3). Light therapy has proven to be an effective treatment for patients with SAD (4–9). Although effective, light treatment response in SAD is not as complete as spontaneous remission in the summer (10). However, a significant proportion of patients with SAD do not remit with light treatment (47%), especially those with more severe symptoms (11).

At this point, the optimal administration of light treatment has not been established, as its parameters including intensity, duration, angle, and timing have not been thoroughly compared using dose- response and delivery- response curves (12). Light intensity is a very important parameter of light treatment, in addition to timing, duration of a session, duration of a course, and wavelength. General light therapy procedures include positioning the light source at a fixed distance from the patient’s eyes to ensure a minimum ocular illuminance (with distance dependent on the specific light treatment device). The patient is instructed to glance (‘sample’) the light only occasionally, while performing other compatible activities including reading, writing, listening to music, grooming, eating, paying bills, planning and talking on the phone (1, 8, 13, 14). A diffuse illumination of the retina is hypothesized to optimally stimulate the receptors implicated in the antidepressant response to light in SAD (8, 14). Until now, however, the question of whether there may be specific activities that have the potential to influence the efficacy of light during light therapy sessions has remained largely unexplored.

Our recent research (Bose et al., unpublished) investigated the specific activities that individuals engaged in during their daily light therapy sessions throughout a 6-week clinical trial. These activities were then correlated with weekly depression scores, as rated by the structured interview guide for the hamilton depression rating scale – seasonal affective disorders (SIGH-SAD) (15). The resulting analysis revealed that only one activity, reading, had a significant positive association with clinical outcome (Bose et al., unpublished). Specifically, the relative duration of reading was associated with a greater likelihood of remission at the end of 6-weeks of light treatment.

This association may be explained by psychological, physiological or physical factors. The aim of this study is to investigate possible physical parameters that might contribute to improved mood scores when the subject is reading during light therapy. Specifically, we hypothesize a greater ocular illumination when reading during light therapy because, in addition to the luminous flux emitted from the light box, the subject is exposed to added light reflected off of the reading material.

Methods

Two technicians naïve to our hypothesis measured the amount of reflected light from a page of various printed reading materials within a comfortable reading distance of the light source. The device used to administer light was the light box used in the parent study (Phillips BrightLight 6, Phillips/Apollo Health, American Fork, UT, USA, dimensions: 7.1 in×11 in×17.4 in, i.e., 18 cm×28 cm×44 cm, total illuminance: 10,050 lux, peak wavelength of 545 nm, and total irradiance 3386 μW/cm2). Illuminance was measured with a Kleton K7020 light meter (Projean Instruments, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Multiple measurements (120) under different conditions were recorded in an attempt to mimic naturalistic conditions of light treatment at home. Some of the locations were near the window, and thus were exposed to natural sunlight, whereas others were in rooms with no windows.

Illuminance at eye position was measured under two conditions (reading material present or absent) in each of the designated locations. The reflected light was measured with the reading material in front and to the side of the light box at a comfortable reading distance that also maintained the distance of 34 cm from the center of the light box to the subject’s glabella. The light meter was positioned at the observer’s eye level at the designated distance, and angled obliquely downward towards the center of the reading material (as a person would naturally read a book or any other material) to measure the light reflected from the center of the reading material. In the second condition, the same measurements were recorded without the reading material present.

Whether or not reading material was present and the orders of locations were randomized using an internet number randomization program (16). Ambient light measurements were obtained prior to turning on the light box. Each light box was kept on for 5 min before the light measurements were taken in order to allow the light box to achieve a steady state. A 34 cm ribbon was attached to the top of the light box to indicate the distance to hold the light meter from the light box. It is important to emphasize that although the distance was measured from the photometer to the light box (34 cm), the photometer was directed towards the center of the reading material when present, and remained steady in the direction of the reading material after the material had been removed. The reading material was never positioned to block the path of light from the light-box to the photometer.

A comparison of the conditions (reading material present or absent) obtained for hypothesis testing was performed by a Friedman repeated-measure non-parametric analysis of variation (ANOVA) test. If a significant main effect of ‘reading material’ was observed, Wilcoxon tests were used to compare light intensity with vs. without reading material.

Results

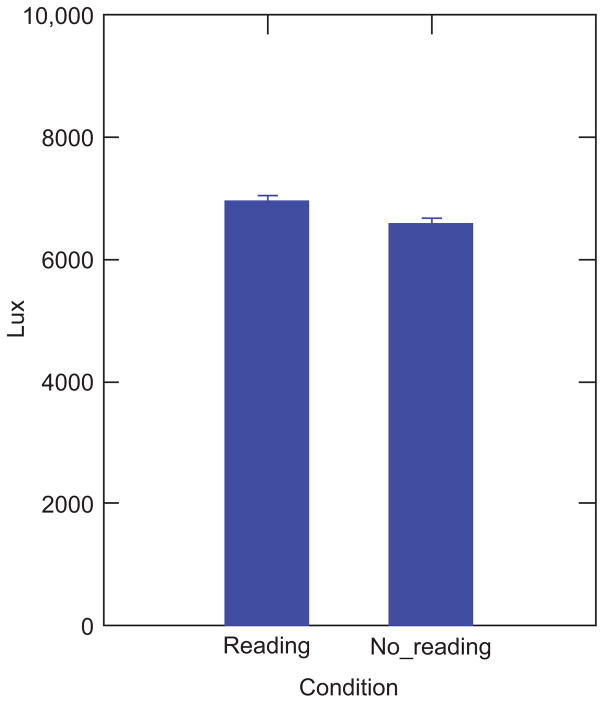

Baseline average light before turning on the light box measured 781 lux (95% confidence interval, CI, 271–1292). After the light box was turned on and had reached steady state, the light intensity reading with the light meter directed towards the center of the light box was calibrated at 10,050 lux. With the light meter in this position, the light measured 7223 (1563) lux and with the reading material removed it measured 6752 (1426) lux (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in light intensity with and without reading material during light treatment, when the light meter is directed away from the light box in the direction of the reading material.

Mean and standard errors are illustrated. Light intensity with reading material present was 7223 (150) lux and without reading material was 6752 (137) lux. The difference of 471 lux (95% CI 300–642) was statistically significant (p<0.0001).

The repeated measures Friedman’s ANOVA revealed a significant effect of ‘reading material’ (Friedman’s test statistic=16.333, p=0.000053). The presence of the reading material increased the light intensity by an average of 470.93 lux (95% CI 300.10–641.75, significant by Wilcoxon signed rank test, z=5.047, p=0.0001).

Discussion

These results indicate that when gaze is directed away from the light box during light therapy, the presence of reading material significantly increases the amount of light that the individual receives. According to our measurements, reading material reflects about 5% of incident light, increasing the ocular illuminance above that which is provided solely by the light box. This increase in illuminance may be responsible for greater reduction in depression scores associated with reading compared to other activities during light treatment.

Although these preliminary findings may have wider implications for SAD management protocols in the long-term, caution should be taken in interpreting the results. Ratios of time spent gazing directly at the light box to time spent looking away from it (as required by reading) might differ between individuals. People may be ‘sampling’ the light source directly for a shorter duration of time when engaged in reading and, thus, might actually be exposed to less light during an entire light therapy session relative to those not engaged in reading. The spectral composition of reflected light from the pages of reading materials may contain larger proportions of short wavelength light. Recent data suggest that treatment with light having lower overall illuminance but high short-wavelength emission may be as effective an antidepressant as brighter light (17, 18); this needs to be studied in its own right. The angle of light reflected from the reading material may stimulate higher or lower melanopsin-containing cells, although there are no current findings to support a localized distribution of these cells in the retina. Factors other than an increase in light intensity may mediate a potential augmentation of antidepressant effect of reading during light treatment, including exposing a larger retinal surface to light as the eyes move across the page, more dilated pupils, or a psychological process, such as distraction or perceived mastery.

Compliance with light therapy may have been increased in the cohort that elected to read because reading-associated reflected light might have been perceived as pleasurable. Reading may also be considered by some to be a very pleasurable activity in its own right, encouraging them to comply with light treatment as a designated ‘sanctuary of time’ to read. The observation of a greater improvement in mood with reading during light treatment is purely an association, and may have an underlying reverse causality, for example people who are less depressed may be more able to read. Assuming that the great majority of patients will prefer in a position favoring an increased rather than decreased illumination of the reading material, especially in bright light, we did no measurements with the reading material blocking the path of light from the light box to the photometer. This assumption may be incorrect, as, certain patients, for instance those with migraine headaches, may have a tendency to reduce light exposure. Our preliminary report would need to be replicated in clinical treatment conditions with real patients blind to study hypothesis.

Longitudinal studies with randomization (to read or do other activities) and repeated measurements of light therapy behaviors and depression over the course of treatment would allow the detection of relevant temporal sequences (i.e., mediation) and increase confidence in making inferences about causality. Further investigation into whether the resultant small difference in lux from reflected material is clinically meaningful (i.e., actually leads to better mood scores), needs to be undertaken.

This is a first report, carried out in a laboratory setting, but attempting to mimic naturalistic conditions. Ideally, the exact amount of light exposure obtained from a continuously recording photometer would be used to estimate actual light exposure. Replication in a clinical setting with randomized design is needed before clinical recommendations are considered.

Beyond Seasonal Affective Disorder, the finding that bright light is significantly reflected towards the eye by reading material raises important circadian considerations. Many individuals read at night, most commonly using lights that contain wavelengths that can phase-delay circadian rhythms. This is particularly important in adolescents and college students, who have a tendency for a circadian phase delay, staying awake late into the night, and, often sacrificing early night sleep to study. Reflection of light by the reading material during a sensitive time period may induce or exacerbate a preexisting circadian phase delay, a condition that contributes to sleep deprivation, sleepiness in the early hours of school and truancy, with negative consequences on academic functioning and health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Dipika Vaswani, Thea Postolache and Simran Vaswani for their help with logistics. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant number 1R34MHO7397-01A2 (PI Postolache). The NIH had no further involvement in the study.

References

- 1.Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, et al. Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:72–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehr TA, Duncan WC, Jr, Sher L, Aeschbach D, Schwartz PJ, et al. A circadian signal of change of season in patients with seasonal affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1108–14. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavoie MP, Lam RW, Bouchard G, Sasseville A, Charron MC, et al. Evidence of a biological effect of light therapy on the retina of patients with seasonal affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastman CI, Young MA, Fogg LF, Liu L, Meaden PM. Bright light treatment of winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:883–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flory R, Ametepe J, Bowers B. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bright light and high density negative air ions for treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Ekstrom RD, Hamer RM, Jacobsen FM, et al. The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:656–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lieverse R, Van Someren EJ, Nielen MM, Uitdehaag BM, Smit JH, et al. Bright light treatment in elderly patients with non-seasonal major depressive disorder: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:61–70. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, et al. Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:72–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terman M, Terman JS, Ross DC. A controlled study of timed bright light and negative air ionization for treatment of winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:875–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postolache TT, Hardin TA, Myers FS, Turner EH, Yi LY, et al. Greater improvement in summer than with light treatment in winter in patients with seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1614–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terman M, Amira L, Terman JS, Ross DC. Predictors of response and non-response to light treatment for winter depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1423–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitan RD. What is the optimal implementation of bright light therapy for seasonal affective disorder (SAD)? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30:72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partonen T, Pandi-Perumal SR, editors. Seasonal affective disorder: Practice and research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Postolache TT, Oren DA. Circadian phase shifting, alerting, and antidepressant effects of bright light treatment. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:381–413. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams JB, Link MJ, Rosenthal NE, Amira L, Terman M. Structured interview guide for the hamilton depression rating scale, seasonal affective disorders version (SIGH-SAD), revised. New York: New York State Psychiatr Inst; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haahr M. Random.org. The True Random Number Service; [accessed 9 December 2011]. Random number generator. Available at: http://www.random.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JL, Glod CA, Dai J, Cao Y, Lockley SW. Lux vs. wavelength in light treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:203–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meesters Y, Dekker V, Schlangen LJ, Bos EH, Ruite MJ. Low-intensity blue-enriched white light (750 lux) and standard bright light (10,000 lux) are equally effective in treating SAD. A randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;28:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]