Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence of non-acute conditions among patients seeking healthcare in a defined US population, emphasizing age, sex, and ethnic differences.

Methods

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) records-linkage system was used to identify all residents of Olmsted County, MN on April 1, 2009 (n=142,377). We then electronically extracted all International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes received by these subjects from any health care provider between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009. We grouped ICD-9 codes into Clinical Classification Codes (CCCs), and then into 47 broader disease groups associated with health-related quality of life. Age- and sex-specific prevalence was estimated by dividing the number of individuals within each group by the corresponding age- and sex-specific population. People with multiple codes within a group were counted only once.

Results

We included a total of 142,377 subjects (53% women). Skin disorders (42.7%), osteoarthritis and joint disorders (33.6%), back problems (23.9%), disorders of lipid metabolism (22.4%), and upper respiratory disease (22.1%; excluding asthma) were the most prevalent disease groups in this population. Eight of the 10 most prevalent disease groups were more common in women; however, disorders of lipid metabolism and hypertension were more common in men. Additionally, the prevalence of seven of these 10 groups increased with advancing age. Prevalence varied also across whites, blacks, and Asians.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest areas for focused research that may lead to better care delivery and improved population health.

Chronic diseases account for the majority of health care utilization and expenditures in middle-aged and older populations.1–3 As the population ages, more individuals are living with multiple chronic medical conditions. One-fourth of Americans with chronic conditions account for almost two-thirds of the total healthcare expenditures.4 Research on chronic disease has largely focused on a specific group of conditions with high morbidity and mortality (including diabetes and chronic heart disease). However, other types of non-acute conditions, with less severe long-term outcomes, may affect large segments of the population and may account for a substantial amount of healthcare resource utilization. Recognition of these other conditions may suggest new areas for improving healthcare delivery and population health management.

Healthcare reform has intensified the need for information on healthcare resource utilization for non-acute conditions. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act allows the restructuring of Medicare reimbursements into “bundled payments.”5 This restructuring will require the rational deployment of treatment resources to ensure the financial solvency of medical institutions. Additionally, clinical decision support for chronic diseases has been identified as critical for the patient-centered medical home model.6 However, development of these models requires quantification of prevalent chronic diseases across populations.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of disease can be difficult to capture across all age groups, because only a few databases in the US include younger populations. Additionally, it can be difficult to consider the prevalence of multiple conditions concurrently in a single population. Failure to simultaneously consider all possible drivers of health care utilization can result in inefficient targeting of resources to improve population health.

To address these problems, we conducted a study to identify the prevalence of the most common non-acute conditions in a defined US population, using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP records-linkage system provides an ideal opportunity to quantify the prevalence of all medical conditions in an entire population, across age, sex, and ethnic groups, regardless of socioeconomic or insurance status.7

METHODS

Study Population

The REP links data on medical care delivered to the population of Olmsted County, MN. 7–9 The vast majority of medical care in this community is currently provided by a few health care institutions: the Mayo Clinic and its two affiliated hospitals, Olmsted Medical Center and its affiliated hospital, and the Rochester Family Medicine Clinic. The health care records from these institutions are linked together through the REP records-linkage system.8,9 A patient is defined as a resident or nonresident of Olmsted County at the time of each health care visit based on his or her address. Over the years, this address information has been accumulated and is used to define who resided in Olmsted County at any given point in time since 1966 (REP Census). The population counts obtained by the REP Census are similar to those obtained by the US Census, indicating that virtually the entire population of the county is captured by the system.8,9 We used the REP Census to identify all individuals who resided in Olmsted County on April 1, 2009, but we excluded those individuals who had not given permission to at least one health care institution for their medical records to be used for research.8

Definition of Disease Groups

The diagnostic indices of the REP were searched electronically to extract all International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes that members of the Olmsted County population received from any health care institution from 2005 through 2009. These ICD-9 codes were first grouped into Clinical Classification Codes (CCCs) proposed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.10,11 For this study, we focused specifically on conditions that were not likely to resolve in a short period of time and which were likely to require multiple health care visits over several years for evaluation and treatment. However, these conditions were not confined to conditions typically considered “chronic diseases” such as diabetes and heart disease. For example, we included conditions such as tuberculosis, back problems, and esophageal disorders. We excluded conditions related to dental or vision problems because the REP does not capture all data from local dentists or optometrists. These CCCs were then combined into broader disease groups that have been associated with health-related quality of life, such as cancer, diabetes, thyroid disorders, and heart failure according to the classification system developed by Mukherjee et al.11,12 We modified this system by using updated CCCs, and by including breast, uterine, ovarian, and prostate cancer in the cancer category, but excluding benign neoplasms and neoplasms of uncertain malignancy.12 The final CCCs used for this study and the modified disease groups are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Statistical Analyses

The point prevalence of each CCC was measured using April 1, 2009 as the prevalence day.13 The history of a given disease on the prevalence day was derived from a 5-year capture time frame (the 5 years preceding the prevalence day). In general, for non-acute conditions, our findings should be comparable to point prevalence figures derived from a population survey.13 The crude age- and sex-specific prevalence of each of the 47 disease groups was estimated by dividing the number of individuals in a group by the corresponding age- and sex-specific Olmsted County population on the prevalence day. These prevalence figures were directly standardized to the 2000 total US population by age and by sex when appropriate to make comparisons of aggregated data (2000 US Census). This study covered the target population completely, and no sampling was involved. For this reason, statistical tests may not be appropriate, and confidence intervals were not included in the tables.14–16

RESULTS

Description of the Olmsted County Population

Overall, the REP infrastructure captured 146,687 Olmsted County, MN residents in 2009 compared with 143,962 individuals predicted by the US Census.17 Therefore, the REP captured slightly more people than the US Census (101.9%). These results are consistent with a previous study which examined REP capture rates between 1970 and 2000.8

Of 146,687 residents, 142,377 gave permission for medical record research (97.1%). Women were slightly more likely to refuse research authorization than men (2.5% vs 2.1%), and parents of children <20 years of age were more likely to have refused authorization than adults 20 years or older (4.2% vs 1.9%). Fifty-three percent of the population were women (or girls). Age and sex distributions were virtually identical to US Census estimates. However, the proportion of people in the “white” ethnic category was lower, and the proportion in the “other/unknown” ethnic category was higher compared to US Census estimates. Because we presume that most of the people in the “other/unknown” category were white (85.7% of the population self-reported white ethnicity in the 2010 census), we grouped the other/unknown category with the white category.

Results by Broad Disease Groups

Table 1 shows the 20 most prevalent conditions. Data for the remaining 27 disease groups are shown in Supplemental Table 2. Skin disorders were the most prevalent disease group in this population. Almost half of the population (42.7%) received at least one ICD-9 code for a skin condition within approximately five years. Skin disorders were followed in frequency by osteoarthritis and joint disorders (33.6%), back problems (23.9%), disorders of lipid metabolism (22.4%), and upper respiratory disease (22.1%). By contrast, systemic lupus erythematosus and connective tissue disorders, tuberculosis, HIV infection, sickle cell anemia, and cystic fibrosis were the least prevalent conditions (Supplemental Table 2). Seven of the 10 most prevalent disease groups increased with advancing age (Table 1). However, the prevalence of upper respiratory disease remained relatively consistent across all age groups. The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorders was low in 0–18 year olds, increased dramatically in 19–29 year olds, and remained constant across the older age groups. Headaches, including migraine, also increased in the 19–29 year olds, but declined after age 50 years.

Table 1.

Age- and sex-specific prevalence (per 100 population) of the 20 most common chronic disease groups in the 2009 Olmsted County, MN, population (N=142,377)a

| Chronic disease group | Age (years)

|

All ages

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–18

|

19–29

|

30–49

|

50–64

|

65+

|

Crudeb

|

Standardizedc

|

||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Skin disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 12,703 | 32.95 | 9170 | 38.26 | 15,652 | 41.27 | 12,390 | 50.39 | 11,398 | 65.75 | 61,313 | 43.06 | 61,313 | 42.67 |

| Men | 6232 | 31.78 | 3247 | 31.41 | 5923 | 33.11 | 5221 | 45.42 | 4980 | 66.11 | 25,603 | 38.29 | 25,603 | 38.43 |

| Women | 6471 | 34.15 | 5923 | 43.45 | 9729 | 48.55 | 7169 | 54.76 | 6418 | 65.47 | 35,710 | 47.29 | 35,710 | 46.90 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Osteoarthritis and joint disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 5580 | 14.47 | 6044 | 25.22 | 13,122 | 34.60 | 12,275 | 49.92 | 10,971 | 63.28 | 47,992 | 33.71 | 47,992 | 33.58 |

| Men | 2859 | 14.58 | 2752 | 26.62 | 5832 | 32.60 | 5223 | 45.43 | 4273 | 56.72 | 20,939 | 31.32 | 20,939 | 31.72 |

| Women | 2721 | 14.36 | 3292 | 24.15 | 7290 | 36.38 | 7052 | 53.87 | 6698 | 68.33 | 27,053 | 35.83 | 27,053 | 35.13 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Back problems | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 2193 | 5.69 | 4890 | 20.40 | 11,054 | 29.15 | 8287 | 33.70 | 7692 | 44.37 | 34,116 | 23.96 | 34,116 | 23.90 |

| Men | 1050 | 5.35 | 1653 | 15.99 | 4588 | 25.65 | 3508 | 30.52 | 2966 | 39.37 | 13,765 | 20.59 | 13,765 | 21.12 |

| Women | 1143 | 6.03 | 3237 | 23.75 | 6466 | 32.27 | 4779 | 36.50 | 4726 | 48.21 | 20,351 | 26.95 | 20,351 | 26.48 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Disorders of lipid metabolism | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 135 | 0.35 | 704 | 2.94 | 7261 | 19.15 | 11,948 | 48.59 | 12,143 | 70.05 | 32,191 | 22.61 | 32,191 | 22.39 |

| Men | 75 | 0.38 | 330 | 3.19 | 4247 | 23.74 | 6110 | 53.15 | 5463 | 72.52 | 16,225 | 24.27 | 16,225 | 24.74 |

| Women | 60 | 0.32 | 374 | 2.74 | 3014 | 15.04 | 5838 | 44.59 | 6680 | 68.14 | 15,966 | 21.14 | 15,966 | 20.19 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Other upper respiratory disease | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 9184 | 23.82 | 4597 | 19.18 | 8436 | 22.24 | 5339 | 21.71 | 3941 | 22.73 | 31,497 | 22.12 | 31,497 | 22.10 |

| Men | 5033 | 25.66 | 1765 | 17.08 | 3470 | 19.40 | 2221 | 19.32 | 1717 | 22.79 | 14,206 | 21.25 | 14,206 | 21.16 |

| Women | 4151 | 21.91 | 2832 | 20.78 | 4966 | 24.78 | 3118 | 23.82 | 2224 | 22.69 | 17,291 | 22.90 | 17,291 | 22.99 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 2559 | 6.64 | 5577 | 23.27 | 9927 | 26.17 | 6127 | 24.92 | 4156 | 23.97 | 28,346 | 19.91 | 28,346 | 19.75 |

| Men | 1179 | 6.01 | 1775 | 17.17 | 3453 | 19.30 | 2139 | 18.61 | 1346 | 17.87 | 9892 | 14.79 | 9892 | 15.09 |

| Women | 1380 | 7.28 | 3802 | 27.89 | 6474 | 32.31 | 3988 | 30.46 | 2810 | 28.67 | 18,454 | 24.44 | 18,454 | 24.13 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Chronic neurologic disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 2774 | 7.19 | 2812 | 11.73 | 7482 | 19.73 | 6829 | 27.77 | 8324 | 48.02 | 28,221 | 19.82 | 28,221 | 19.75 |

| Men | 1519 | 7.75 | 995 | 9.63 | 2929 | 16.37 | 2894 | 25.17 | 3412 | 45.29 | 11,749 | 17.57 | 11,749 | 17.92 |

| Women | 1255 | 6.62 | 1817 | 13.33 | 4553 | 22.72 | 3935 | 30.06 | 4912 | 50.11 | 16,472 | 21.81 | 16,472 | 21.43 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 108 | 0.28 | 513 | 2.14 | 4450 | 11.73 | 8918 | 36.27 | 12,251 | 70.67 | 26,240 | 18.43 | 26,240 | 18.21 |

| Men | 64 | 0.33 | 269 | 2.60 | 2444 | 13.66 | 4514 | 39.27 | 5290 | 70.22 | 12,581 | 18.82 | 12,581 | 19.22 |

| Women | 44 | 0.23 | 244 | 1.79 | 2006 | 10.01 | 4404 | 33.64 | 6961 | 71.01 | 13,659 | 18.09 | 13,659 | 17.22 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Headaches; including migraines | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 3286 | 8.52 | 4135 | 17.25 | 6753 | 17.81 | 3745 | 15.23 | 2302 | 13.28 | 20,221 | 14.20 | 20,221 | 13.99 |

| Men | 1446 | 7.37 | 1020 | 9.87 | 1918 | 10.72 | 1162 | 10.11 | 766 | 10.17 | 6312 | 9.44 | 6312 | 9.53 |

| Women | 1840 | 9.71 | 3115 | 22.85 | 4835 | 24.13 | 2583 | 19.73 | 1536 | 15.67 | 13,909 | 18.42 | 13,909 | 18.32 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 221 | 0.57 | 724 | 3.02 | 4181 | 11.02 | 6897 | 28.05 | 7872 | 45.41 | 19,895 | 13.97 | 19,895 | 13.78 |

| Men | 108 | 0.55 | 241 | 2.33 | 2091 | 11.69 | 3658 | 31.82 | 3723 | 49.42 | 9821 | 14.69 | 9821 | 14.94 |

| Women | 113 | 0.60 | 483 | 3.54 | 2090 | 10.43 | 3239 | 24.74 | 4149 | 42.32 | 10,074 | 13.34 | 10,074 | 12.82 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Arrhythmias | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 750 | 1.95 | 1689 | 7.05 | 3874 | 10.21 | 4403 | 17.91 | 7988 | 46.08 | 18,704 | 13.14 | 18,704 | 13.03 |

| Men | 348 | 1.78 | 584 | 5.65 | 1574 | 8.80 | 2227 | 19.37 | 3826 | 50.79 | 8559 | 12.80 | 8559 | 13.21 |

| Women | 402 | 2.12 | 1105 | 8.11 | 2300 | 11.48 | 2176 | 16.62 | 4162 | 42.46 | 10,145 | 13.43 | 10,145 | 13.05 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Esophageal disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 1462 | 3.79 | 1260 | 5.26 | 3973 | 10.48 | 3973 | 16.16 | 4117 | 23.75 | 14,785 | 10.38 | 14,785 | 10.36 |

| Men | 792 | 4.04 | 499 | 4.83 | 1860 | 10.40 | 1765 | 15.35 | 1700 | 22.57 | 6616 | 9.89 | 6616 | 10.08 |

| Women | 670 | 3.54 | 761 | 5.58 | 2113 | 10.54 | 2208 | 16.87 | 2417 | 24.66 | 8169 | 10.82 | 8169 | 10.59 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Asthma | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 4141 | 10.74 | 2108 | 8.80 | 3125 | 8.24 | 1951 | 7.94 | 1424 | 8.21 | 12,749 | 8.95 | 12,749 | 8.88 |

| Men | 2382 | 12.15 | 716 | 6.93 | 1043 | 5.83 | 630 | 5.48 | 493 | 6.55 | 5264 | 7.87 | 5264 | 7.75 |

| Women | 1759 | 9.28 | 1392 | 10.21 | 2082 | 10.39 | 1321 | 10.09 | 931 | 9.50 | 7485 | 9.91 | 7485 | 9.91 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Thyroid disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 305 | 0.79 | 963 | 4.02 | 3546 | 9.35 | 3732 | 15.18 | 4283 | 24.71 | 12,829 | 9.01 | 12,829 | 8.87 |

| Men | 106 | 0.54 | 150 | 1.45 | 638 | 3.57 | 789 | 6.86 | 1091 | 14.48 | 2774 | 4.15 | 2774 | 4.27 |

| Women | 199 | 1.05 | 813 | 5.96 | 2908 | 14.51 | 2943 | 22.48 | 3192 | 32.56 | 10,055 | 13.32 | 10,055 | 13.00 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Deficiency and other anemia | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 868 | 2.25 | 1040 | 4.34 | 2803 | 7.39 | 2751 | 11.19 | 5148 | 29.70 | 12,610 | 8.86 | 12,610 | 8.75 |

| Men | 406 | 2.07 | 163 | 1.58 | 582 | 3.25 | 997 | 8.67 | 2161 | 28.69 | 4309 | 6.44 | 4309 | 6.65 |

| Women | 462 | 2.44 | 877 | 6.43 | 2221 | 11.08 | 1754 | 13.40 | 2987 | 30.47 | 8301 | 10.99 | 8301 | 10.79 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Bowel disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 481 | 1.25 | 630 | 2.63 | 1843 | 4.86 | 4525 | 18.40 | 5195 | 29.97 | 12,674 | 8.90 | 12,674 | 8.68 |

| Men | 253 | 1.29 | 243 | 2.35 | 937 | 5.24 | 2338 | 20.34 | 2459 | 32.64 | 6230 | 9.32 | 6230 | 9.39 |

| Women | 228 | 1.20 | 387 | 2.84 | 906 | 4.52 | 2187 | 16.71 | 2736 | 27.91 | 6444 | 8.53 | 6444 | 8.09 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Cancerd | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 94 | 0.24 | 397 | 1.66 | 1887 | 4.98 | 3272 | 13.31 | 6334 | 36.54 | 11,984 | 8.42 | 11,984 | 8.28 |

| Men | 52 | 0.27 | 85 | 0.82 | 630 | 3.52 | 1483 | 12.90 | 3202 | 42.51 | 5452 | 8.15 | 5452 | 7.62 |

| Women | 42 | 0.22 | 312 | 2.29 | 1257 | 6.27 | 1789 | 13.67 | 3132 | 31.95 | 6532 | 8.65 | 6532 | 8.92 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Biliary and liver disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 1141 | 2.96 | 795 | 3.32 | 3207 | 8.46 | 3392 | 13.80 | 3243 | 18.71 | 11,778 | 8.27 | 11,778 | 8.23 |

| Men | 599 | 3.05 | 242 | 2.34 | 1456 | 8.14 | 1459 | 12.69 | 1443 | 19.16 | 5199 | 7.78 | 5199 | 7.93 |

| Women | 542 | 2.86 | 553 | 4.06 | 1751 | 8.74 | 1933 | 14.77 | 1800 | 18.36 | 6579 | 8.71 | 6579 | 8.53 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Obstructive pulmonary disorders | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 1738 | 4.51 | 1132 | 4.72 | 2816 | 7.43 | 2506 | 10.19 | 3263 | 18.82 | 11,455 | 8.05 | 11,455 | 8.00 |

| Men | 910 | 4.64 | 352 | 3.41 | 1089 | 6.09 | 1097 | 9.54 | 1466 | 19.46 | 4914 | 7.35 | 4914 | 7.47 |

| Women | 828 | 4.37 | 780 | 5.72 | 1727 | 8.62 | 1409 | 10.76 | 1797 | 18.33 | 6541 | 8.66 | 6541 | 8.56 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | ||||||||||||||

| Both sexes | 164 | 0.43 | 156 | 0.65 | 1107 | 2.92 | 3084 | 12.54 | 6833 | 39.42 | 11,344 | 7.97 | 11,344 | 7.87 |

| Men | 88 | 0.45 | 102 | 0.99 | 631 | 3.53 | 1895 | 16.48 | 3513 | 46.64 | 6229 | 9.32 | 6229 | 9.60 |

| Women | 76 | 0.40 | 54 | 0.40 | 476 | 2.38 | 1189 | 9.08 | 3320 | 33.87 | 5115 | 6.77 | 5115 | 6.45 |

Numbers to the left of the prevalence figure indicate the actual number of cases observed. Prevalence can be computed by dividing the number of cases by the corresponding denominator listed below (and multiplying by 100)

Denominators for men and women combined: 0–18=38,558; 19–29=23,968; 30–49=37,927; 50–64=24,588; 65+=17,336

Denominators for men: 0–18=19,611; 19–29=10,337; 30–49=17,888; 50–64=11,496; 65+=7533

Denominators for women: 0–18=18,947; 19–29=13,631; 30–49=20,039; 50–64=13,092; 65+=9803

A crude prevalence was computed by dividing cases observed across all ages by the total population

Overall prevalence for men and women combined was standardized by age and sex; overall prevalence for men and women separately was standardized only by age (direct standardization using the 2000 US census population)

Prevalence for men excluded women’s cancers (ovarian, uterine, etc.) and prevalence for women excluded men’s cancers (prostate, testicular, etc.)

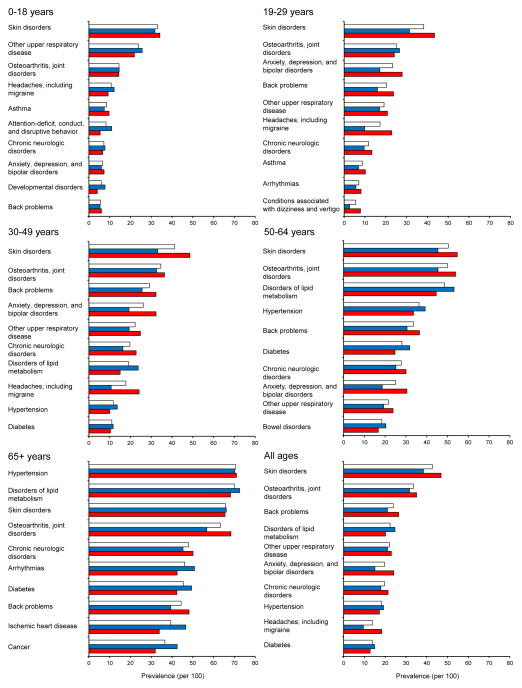

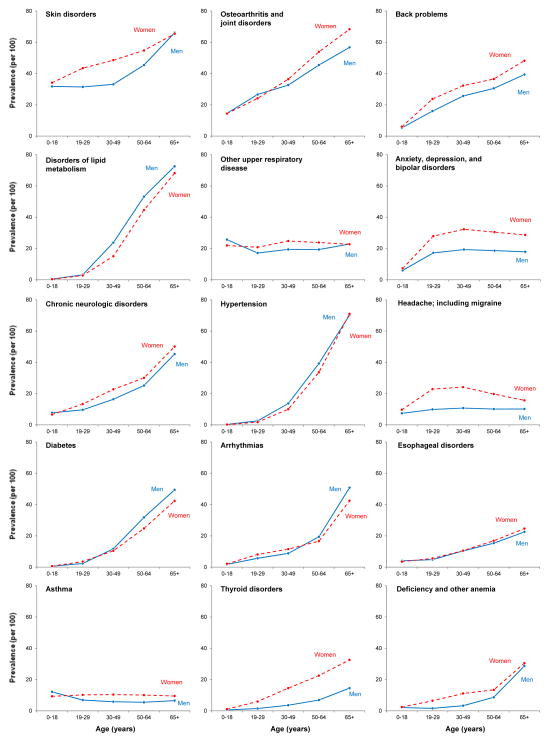

The most prevalent disease groups differed by age. For example, skin disorders were the most prevalent condition in 0–18 year olds, followed by upper respiratory disease and osteoarthritis and joint disorders. By contrast, hypertension was the most prevalent condition in 65+ year olds, followed by disorders of lipid metabolism and skin disorders (Figure 1). Ten of the 15 most prevalent disease groups were more common in women in almost all age groups, whereas disorders of lipid metabolism, hypertension, and diabetes were more common in men (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (per 100 population) of the 10 most prevalent disease groups in five broad age categories and for all ages combined (lower right panel). Prevalence figures were age and sex standardized (when applicable). Prevalence in both sexes is shown with white bars, prevalence in men is shown with blue bars, and prevalence in women is shown with red bars.

Figure 2.

Age-specific prevalence (per 100 population) of the 15 most prevalent disease groups in men (blue line) compared to women (red line). The 15 panels are presented in decreasing order of overall age- and sex-adjusted prevalence (see Table 1).

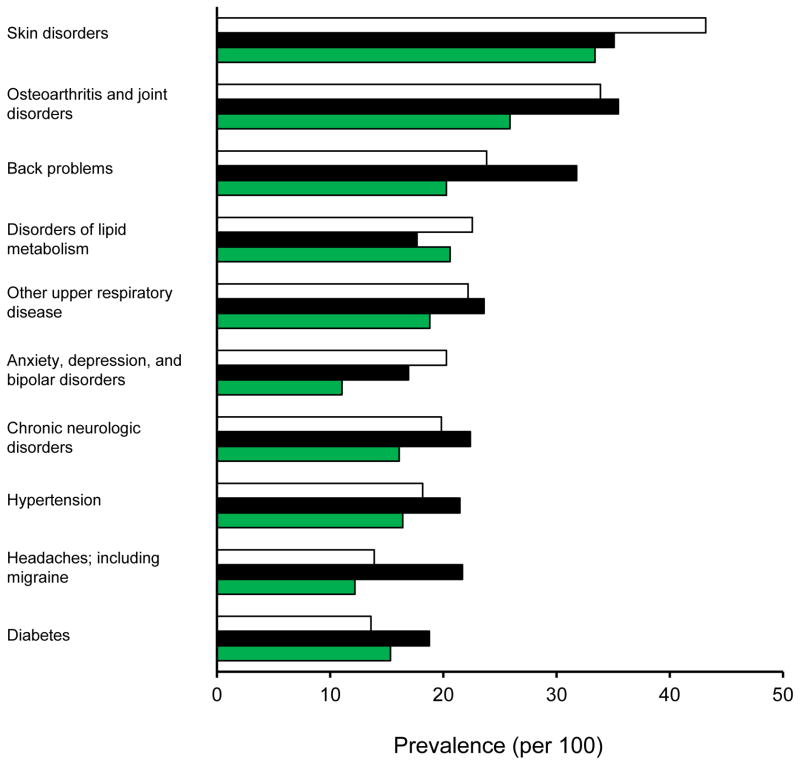

The prevalence of the top 10 disease groups also differed by ethnicity (Figure 3). Blacks had a higher prevalence for 7 of the top 10 disease groups. The biggest differences with blacks higher than whites were for back problems and for headaches, including migraine. By contrast, whites had a higher prevalence of skin disorders compared to both blacks and Asians. Asians had a higher prevalence of diabetes than whites.

Figure 3.

Prevalence (per 100 population) of the 10 most prevalent disease groups by ethnic category. Prevalence figures were standardized by age and sex (when applicable). Prevalence in whites is shown with white bars, prevalence in blacks is shown with black bars, and prevalence in Asians is shown with green bars.

Results for Specific ICD-9 Codes

Although our primary analyses considered a high-level grouping of diseases, we also examined the individual ICD-9 codes within the groups. The prevalence estimates of selected single conditions observed in Olmsted County were generally in agreement with US statistics (Table 2). For example, national prevalence estimates indicate that approximately 30% of the adult population is affected by hypertension, increasing from 29.9% in subjects ≥18 years old to 70.3% in subjects ≥65 years old.18 These numbers were similar to the estimated prevalence of hypertension among the adult Olmsted County population (24.7% in ≥18 year olds and 70.7% in ≥65 year olds). However, there were greater differences for some other diseases. For example, the prevalence of osteoarthritis in people ≥65 years old was 44.4% in Olmsted County compared to 33.6% in the total US population of the same age.19

Table 2.

Comparison of the prevalence (per 100 population) of selected diseases and conditions in the total US population versus the Olmsted County population

| Disease or condition | Age stratum | US Population

|

Olmsted County population Prevalence (%)a |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication | Prevalence (%) | |||||||||||||

| Hypertension | Keenan et al, 201118 | |||||||||||||

| ≥18 years | 29.9 | 24.7 | ||||||||||||

| ≥65 years | 70.3 | 70.7 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mood disorders | Kessler et al, 200541 | |||||||||||||

| 18–29 years | 21.4 | 23.2 | ||||||||||||

| ≥60 years | 11.9 | 23.9 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Diabetes | Centers for Disease Control 42 | |||||||||||||

| ≥20 years | 11.3 | 9.0b | ||||||||||||

| ≥65 years | 26.9 | 23.9b | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Osteoarthritis | Lawrence et al, 200819 | |||||||||||||

| ≥25 years | 13.9 | 18.5 | ||||||||||||

| ≥65 years | 33.6 | 44.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Asthma | Akinbami et al, 201143 | |||||||||||||

| 0–17 years | 9.6 | 10.6 | ||||||||||||

| ≥18 years | 7.7 | 8.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Osteoporosis | Cheng et al, 200944 | |||||||||||||

| ≥65 years | 29.7 | 21.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Prostate cancer | Howlader et al, 201145 | |||||||||||||

| All ages | 1.6c | 2.3 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | Howlader et al, 201145 | |||||||||||||

| All ages | 1.7c | 2.2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Colon cancer | Howlader et al, 201145 | |||||||||||||

| All ages | 0.4c | 0.4 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| HIV infection | MN Department of Health46 | |||||||||||||

| All ages | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||||||||||

Age- and sex- standardized using the 2000 US census population (direct standardization)

Prevalence estimates include only ICD-9 codes for diabetes, not for abnormal glucose tests

Prevalence calculated using the estimated US population on July 1, 2008 (men: 149,924,604; women: 154,135,120; both sexes: 304,059,724).

DISCUSSION

Discussion of Principal Findings

Using the REP records-linkage system, we described the prevalence of the most common medical conditions in a defined US population across all ages, for men and women separately, and across ethnic groups. Surprisingly, the most prevalent non-acute conditions in our community were not chronic conditions related to aging such as diabetes and heart disease but rather conditions that affect both sexes and all age groups: skin disorders, osteoarthritis and joint disorders, back problems, disorders of lipid metabolism, and upper respiratory disease (excluding asthma). The broad disease groups that we examined in this study are useful for describing important drivers of health care utilization which might otherwise be overlooked.

Unexpectedly, almost half of the Olmsted County population of all ages received a diagnosis of “skin disorders” within approximately five years. The skin disorders category was broad and included 19 different ICD-9 groupings (including actinic keratosis, acne, and sebaceous cysts). No single skin disorder was highly prevalent, but skin disorders in combination affected a significant proportion of all age groups in our population. Skin disorders are not typically major drivers of disability or death but may be important determinants of health care utilization and cost. For example, many of the actinic skin issues require continued observation and therapy.20 New models of dermatologic care delivery, such as teledermatology, should be critically explored within US healthcare systems to increase care efficiency and reduce healthcare expenditures.21 Our data suggest that such efficiencies could affect a substantial proportion of the population.

The “osteoarthritis and joint disorders” group was also common in our population. In particular, the ICD-9 code 719.4 (joint pain) accounted for the majority of the diagnoses (82%). Our data suggest that resources to diagnose, treat, and prevent joint pain may be required; however, joint pain occurs for multiple reasons. Overuse and activity injuries can cause short-term pain, whereas chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis and obesity may cause long-term pain.22,23 The underlying etiology of the “joint pain” cannot be determined from the ICD-9 codes, and it will be necessary to acquire additional information to determine the exact health care burden and needs for these patients. Our data point to the need for further study of this common problem and its causes to identify areas for intervention.

“Back problems” were the third most prevalent disease group. Back problems and back pain are highly prevalent in the US,24 and have been previously classified as the eighth most costly chronic condition in subjects age 18 to 64 years.2 Management of back problems can be challenging, and Carey et al noted that patients experience similar outcomes despite a wide variation in care provider, type of treatment, and cost of treatments.25 The implementation of protocols to stratify the management of back pain patients in the primary care setting has been shown to improve health and decrease costs.26 The availability of detailed information from a complete population will allow us to study current treatments for back problems and to evaluate how these treatments compare with evidence-based guidelines.27 Additionally, as with skin conditions, improved management of patients with back problems could affect a substantial proportion of the population.

“Disorders of lipid metabolism” was the fourth most prevalent disease group. Consistent with our observation in Olmsted County, hyperlipidemia is highly prevalent in many populations throughout the US.28 Hyperlipidemia contributes to multiple chronic conditions, but also offers a potential target for intervention. Current guidelines for the treatment of hyperlipidemia clearly identify groups of subjects most likely to benefit from treatment.29 Among patients with diabetes, telephonic management of hyperlipidemia by nurses may hold promise for improving lipid control and reducing costs.30

Finally, “other upper respiratory disease” (excluding asthma) was the fifth most common category in our population. Similar to “skin problems,” the conditions included in “other upper respiratory disease” are not considered major causes of morbidity or mortality. However, these conditions are extremely common, and affect all age groups. Allergic rhinitis accounted for over half of the diagnoses in this category. Allergic rhinitis alone has been estimated to affect up to 40 million Americans, and symptoms are present for more than 4 months of each year in over half of the affected patients.31 Additionally, direct and indirect health care expenditures related to allergic rhinitis were approximately 11.2 billion dollars in 2005.32 Patients with allergic rhinitis often have multiple comorbid conditions including eczema, asthma, chronic sinusitis, and nasal polyps.31,33 Effective treatment of the conditions included in “other upper respiratory disease” may represent an ideal opportunity to improve the healthcare management of a significant proportion of the community.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include access to data on all conditions for an entire population, across age, sex, and ethnic groups. Such data are often difficult to obtain in the US because we lack a centralized health care surveillance system. For example, Medicare data contain similar diagnosis information, but the data are largely limited to the elderly (age 65 years and older). Data from health insurers contain similar diagnostic information, but the populations are limited only to subjects who are insured, and insured subjects may be healthier than the general population.7

The main limitation of our study is the inability to verify the validity of ICD-9 codes. We know from previous REP studies that codes may be assigned in error, and manual review of the medical records is often needed to ascertain whether an individual truly has the disease or condition of interest.34–38 Additionally, we may have missed people who should have been assigned a code of interest, but were not. However, because many of the diagnoses represent chronic conditions, it is likely that affected patients would be seen at least once within the 5-year period. Despite these limitations, and despite differences in the methodology used for calculating prevalence, our prevalence estimates for 10 common chronic conditions were similar to published US population estimates (Table 2). These data suggest that using electronic ICD-9 codes stored for administrative purposes may be useful to estimate prevalence rates for broad groups of diseases and to monitor the health of a given population over time at relatively low cost.

Many ICD-9 codes are non-specific, and it is not clear whether some of these codes (such as “joint pain”) are the first indication of an underlying pathology that might be diagnosed with additional follow-up. Therefore, these data are useful to understand why people were visiting their doctors, but may not be useful to understand the etiology of specific underlying diseases.

Olmsted County, MN is home to the Mayo Clinic, a tertiary referral center with an international reputation. It is possible that patients might move to the area for treatment, and remain as residents of the community. It is also possible that the access to a high number of medical specialists and sub-specialists could result in an increased likelihood of diagnosis of specific conditions. Finally, a larger proportion of the Olmsted County population (22%) is employed by a health care provider compared with the rest of the United States (9%).39,40 If health care employees are more likely to visit a healthcare provider than those not employed by a healthcare provider, our prevalence data could be substantially higher than the rest of the US. However, we compared the prevalence of 10 common conditions in Olmsted County to national prevalence figures and found similar frequencies (Table 2). These comparisons suggest that the in-migration for health care, the higher probability of diagnosis associated with a tertiary care center, and the higher frequency of health care employees in Olmsted County did not artificially inflate the prevalence of the conditions that were studied.

CONCLUSION

We described the prevalence of 47 broad categories of non-acute conditions across all age groups, in men and women separately, and across ethnic groups in the Olmsted County population. The data provide insight into current health care use in a defined US population and may predict future health care service and work force needs as well as opportunities for prevention. Finding that skin and back problems are major drivers of health care utilization affirms the importance of moving beyond the commonly recognized health care priorities such as diabetes, heart disease, or cancer. Our findings highlight opportunities to improve healthcare and decrease costs related to common non acute conditions as we move forward through the changing healthcare landscape.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Rochester Epidemiology Project infrastructure is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG034676). This project was also supported by funding from the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (UL1 RR024150).

We thank Lori Klein for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Selected Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CCCs

Clinical Classification Codes

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, et al. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:267–278. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naessens JM, Stroebel RJ, Finnie DM, et al. Effect of multiple chronic conditions among working-age adults. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22 (Suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a Multicondition Collaborative Care Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506–514. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussey PS, Ridgely MS, Rosenthal MB. The PROMETHEUS bundled payment experiment: slow start shows problems in implementing new payment models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2116–2124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates DW, Bitton A. The future of health information technology in the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:614–621. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, et al. Generalizability of Epidemiologic Findings and Public Health Decisions: An Illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed February 7, 2011];Clinical Classification Code to ICD-9-CM Code Crosswalk. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h120/h120_icd9codes.shtml.

- 11. [Accessed February 1, 2012];Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Website. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 12.Mukherjee B, Ou HT, Wang F, et al. A new comorbidity index: the health-related quality of life comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porta MS International Epidemiological Association. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. 5. xxiv. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson DW, Mantel N. On epidemiologic surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:613–619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deming WE. Boundaries of Statistical Inference. In: Smith H, Johnson NL, editors. New Developments in Survey Sampling. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1969. pp. 652–670. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Cha RH, Waring SC, et al. Incidence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a reanalysis of data from Rochester, Minnesota, 1975–1984. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:51–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed August 1, 2012];Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates: State and County Estimates for. 2009 http://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/data/statecounty/data/2009.html.

- 18.Keenan NL, Rosendorf KA. Prevalence of hypertension and controlled hypertension - United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60 (Suppl):94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko CJ. Actinic keratosis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijden JP, de Keizer NF, Bos JD, et al. Teledermatology applied following patient selection by general practitioners in daily practice improves efficiency and quality of care at lower cost. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1058–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sowers MR, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA. The evolving role of obesity in knee osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:533–537. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833b4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, et al. The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:913–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510053331406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1560–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60937-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol--United States, 1999–2002 and 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer HH, Eisert SL, Everhart RM, et al. Nurse-run, telephone-based outreach to improve lipids in people with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathan RA. The burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28:3–9. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinitis: Direct and indirect costs. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:375–380. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ker J, Hartert TV. The atopic march: what’s the evidence? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:282–289. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leibson CL, Brown AW, Ransom JE, et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury across the full disease spectrum: a population-based medical record review study. Epidemiology. 2011;22:836–844. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318231d535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leibson CL, Naessens JM, Brown RD, Jr, et al. Accuracy of hospital discharge abstracts for identifying stroke. Stroke. 1994;25:2348–2355. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.12.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leibson CL, Needleman J, Buerhaus P, et al. Identifying in-hospital venous thromboembolism (VTE): a comparison of claims-based approaches with the Rochester Epidemiology Project VTE cohort. Med Care. 2008;46:127–132. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roger VL, Killian J, Henkel M, et al. Coronary disease surveillance in Olmsted County objectives and methodology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yawn BP, Wollan P, St Sauver J. Comparing shingles incidence and complication rates from medical record review and administrative database estimates: how close are they? Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Occupational Employment Statistics: May 2011 Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Area Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates. Rochester, MN: [Accessed August 1, 2012]. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_40340.htm#29-0000. [Google Scholar]

- 40. [Accessed August 1, 2012];Occupational Employment Statistics: May 2011 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates by Ownership Cross-Industry, Private Ownership Only. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/000001.htm.

- 41.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet. Centers for Disease Control; [Accessed February 8, 2012]. Website. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates11.htm#1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng H, Gary LC, Curtis JR, et al. Estimated prevalence and patterns of presumed osteoporosis among older Americans based on Medicare data. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1507–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. [Accessed February 2, 2012];SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerbasics/cancer-prevalence.

- 46.HIV/AIDS Prevalence and Mortality Tables - 2010. Minnesota Department of Health; [Accessed February 8, 2012]. Website. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/diseases/hiv/stats/pmtables2010.html#table1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.