Abstract

Background

Orthopaedic surgery practices can provide substantial value to healthcare systems. Increasingly, healthcare administrators are speaking of the need for alignment between physicians and healthcare systems. However, physicians often do not understand what healthcare administrators value and therefore have difficulty articulating the value they create in discussions with their hospital or healthcare organization. Many health systems and hospitals use service lines as an organizational structure to track the relevant data and manage the resources associated with a particular type of care, such as musculoskeletal care. Understanding service lines and their management can be useful for orthopaedic surgeons interested in interacting with their hospital systems.

Questions/purposes

We provide an overview of two basic types of value orthopaedic surgeons create for healthcare systems: financial or volume-driven benefits and nonfinancial quality or value-driven patient care benefits.

Methods

We performed a search of PubMed from 1965 to 2012 using the term “service line.” Of the 351 citations identified, 18 citations specifically involved the use of service lines to improve patient care in both nursing and medical journals.

Results

A service line is a structure used in healthcare organizations to enable management of a subset of activities or resources in a focused area of patient care delivery. There is not a consistent definition of what resources are managed within a service line from hospital to hospital. Physicians can positively impact patient care through engaging in service line management.

Conclusions

There is increasing pressure for healthcare systems and hospitals to partner with orthopaedic surgeons. The peer-reviewed literature demonstrates there are limited resources for physicians to understand the value they create when attempting to negotiate with their hospital or healthcare organization. To effectively negotiate for resources to provide the best care for patients, orthopaedic surgeons need to claim and demonstrate the value they create in healthcare organizations.

Introduction

Physicians interested in having a greater role in directing hospital resources dedicated to their area of patient care may want to partner with their healthcare systems or hospitals. There are two ultimate goals of partnering between orthopaedic surgeons and hospitals: to direct hospital resources in ways that improve musculoskeletal patient care and to identify goals and incentives in the delivery of care that mutually apply to orthopaedic surgeons and hospitals. The surgeon entering into discussions concerning allocation of resources should recognize this is a negotiation. It is useful for orthopaedic surgeons entering these discussions to understand what healthcare administrators perceive as value that arises from a surgical practice. Hospital administrators may choose to direct more resources toward patients of surgeons who are able to generate high margins for the hospital through their clinical activity [35]; orthopaedic surgeons can be in this group of profitable providers. Not all orthopaedic surgery practices are profitable for hospitals. Whether the practice is profitable or not, it is important to be able to articulate the value an orthopaedic practice creates for its health system. There are two basic types of value orthopaedic surgeons bring to healthcare systems: financial or volume-driven and nonfinancial or quality or value-driven.

Many health systems and hospitals use service lines as an organizational structure to track the relevant data and manage the resources associated with a particular type of care, such as musculoskeletal care [16, 23, 33]. A service line is a structure used in healthcare organizations to enable expense management and information reporting about a subset of activities in a focused area such as musculoskeletal care [12, 33]. The service line is a form of management that considers most or all aspects of patient care for a specific set of medical conditions, typically from the perspective of the managing organization, such as a hospital or healthcare system. In many settings, orthopaedic surgeons use their service line data to identify the impact their practices generate for their hospitals or health systems. Developing an understanding of service lines and their management can be useful for orthopaedic surgeons interested in interacting with their hospital systems. Whether working in a not-for-profit hospital or a physician-owned surgery center, how an orthopaedic surgeon relates to his or her service line is similar.

We therefore discuss the ways in which an orthopaedic surgery practice can create value for a health system or hospital. Specifically, we review concepts related to service lines, understanding financial performance, and explaining financial and nonfinancial advantages to hospitals. This information is important leverage when negotiating with healthcare administrators for realignment of resources for patient care or alignment of incentives.

Search Strategy and Criteria

We performed a search of PubMed for the period of 1965 to 2012 using the term “service line.” Articles were reviewed for relevance to activities in which the physicians had a role in managing resources to improve or enhance orthopaedic surgery or surgery patient care. Articles with strictly financial analysis without consideration of patient care impact were not considered. A total of 351 citations were identified. The majority of citations were from the healthcare administration literature. We identified 18 citations as specifically involving the use of service lines to improve patient care in both nursing and medical journals.

Service Lines

There is no uniform agreement on the structure or composition of clinical services that will comprise a specific service line. There is variability in the organization and resources managed in service line structures from hospital to hospital. Service line leadership may consist of a service line administrator, a service line nursing manager, and or a service line medical director [33–35]. Depending on the complexity and integration of the organization, there may be only a single administrator or three or more leadership positions in an individual service line. Often, the principles of management accounting are applied through the service line structure [33–35]. As with many larger organizations, health system and hospital leadership need to understand the resources needed to provide care for patients within a service line and track the revenue that follows those medical services. In most hospitals, all efforts in a clinical area, including financial performance, customer satisfaction, improvements in quality and safety, and regulatory compliance, are reported through the service line structure.

Patterson [23] reviewed the evolution of service lines in medicine. In the late 1970s and 1980s, attempts to direct care with service lines fell out of favor as they were not responsive to payment restrictions that Medicare and other insurers began to institute. However, in the past 10 years, there has been resurgence in interest in service line management [9, 11, 16, 28, 34]. Hospitals recognize the need to engage physicians regarding the variability in cost of delivering care [34]. Physicians need to be advocates for patient care as this variability in delivering care is addressed [4, 26]. One of the first areas of medicine to be successful in service line management is cardiovascular disease [17, 21, 29]. Examples from family practice, mental health, and general surgery are also reported [2, 9, 27]. There are several reports specific to orthopaedic surgery.

Ranawat et al. [24] reported examples of successful partnering between physicians and hospital administration to improve care at The Hospital for Special Surgery (New York, NY, USA) in three distinct clinical areas of musculoskeletal care. Kwon et al. [16] reported on the successful implementation of a service focused on patients with spine-related disease, for both surgical and nonsurgical care. Saver [25] reported on successes in partnering between nursing and orthopaedic surgeons in improving the perioperative care for their patients.

Several authors [10, 13, 28] have emphasized the importance of physicians becoming more engaged in service line management. These authors identified the need for physicians to be able to recognize and represent the value they create when negotiating for resources. In many organizations, the service line is used primarily as way to react to adverse changes in one or more service line metrics being monitored by the hospital administration. As an example, the administrator may identify a reduction in net revenue for a service or procedure. This may be tracked to an increase in expense of the resources needed to provide the service. The administrator reacts to this change in revenue by developing an intervention to limit access to the most costly resources to address the increased expenses. However, as physicians often drive utilization of resources, the administrator may be ineffective in restricting access without actively engaged physicians in leadership of the service lines. The challenge for most service line administrators in this situation is managing the physician practices that drive the use of resources in providing care for the patients. It may be that use of a more expensive resource leads to improved patient outcomes or that physician preferences in use of implants may drive such an increase in expense without change in patient outcome. Health systems and hospitals need physicians to be engaged in service line development and management to be able to make informed decisions that are financially responsible and consider the impact on patient outcomes. Recognition of this fact is important for orthopaedic surgeons. Superimposed on this discussion is the changing environment of health care. This transition from the traditional paradigm that is volume- and margin-driven to a paradigm of quality of care and performance metrics also requires engaged physicians to be successful. Unfortunately, most physicians receive no formal training in healthcare administration in medical education. Service line management represents the skills and knowledge necessary for physician leaders to take an active role in impacting their practice environments within hospital systems.

Understanding Financial Performance

In the traditional paradigm of health care, the ability of a surgeon or groups of surgeons to contribute to the hospital’s financial bottom line by consistently attracting elective surgical volume to a hospital for care is seen as valuable. To understand this from the hospital administrator’s perspective, it is important to understand key aspects of hospital finance. Hospitals, like major corporations, do not use cash-based accounting in day-to-day operations. Instead, they use an accounting technique based on the matching principle of allocation of revenue and expenses [3]. Using this principle, the business should match the revenue from the sale (delivery of goods or services) with its associated costs or expenses to determine profits in a given period of time—usually a month, quarter, or year. An example to illustrate the point is taken from a finance text [3]. A store buys a truckload of ink cartridges in May to sell over the coming months. The cost of the cartridges is not recorded in May. Instead, the cost of each cartridge is recorded when the cartridge is sold along with the anticipated sales revenue because of the matching principle. The expense associated with the item is “matched” with the revenue associated with that item. Further, companies record a “sale” of an item (and its associated expense) when the item is sold or delivered but not necessarily paid for [3]. Hospitals use this same practice. The chief executive officer or chief financial officer closely tracks hospital discharge volumes or surgical case volumes, the surrogate for sale of a product or service [35]. In health care, as in most major corporations, profit is an estimate of the anticipated revenue and the allocated expense.

Like many large corporations, hospitals have developed methods to understand and allocate the costs of a healthcare episode. These costs are generally thought of in two general ways: direct and indirect costs and fixed and variable costs [35]. Direct costs are expenses that result from services or resources used in the process of providing care to a patient. Direct costs could include the cost of a surgical implant used in a patient’s care or the salary of the operating room nurses who were involved in a patient’s care; they are directly linked to the care of a patient. The resources considered direct costs may vary slightly from hospital to hospital. Ultimately, the chief financial officer of the organization determines what costs are direct or indirect. Generally, if the use of a resource can be linked directly to an event of care with a specific patient, it is considered a direct expense. For example, direct costs may include the cost of radiographs and the incremental salary of the radiology technician who performed the study. Indirect costs are expenses associated with services or resources used to support the ability to provide health care but not directly linked to the care of a patient. Indirect expenses include those often thought of as overhead, such as electricity, laundry services, or amortized debt the hospital is paying. The terms “fixed” and “variable” are used to describe whether the expense is accrued with each episode of patient care or not. A fixed expense does not change with incremental episodes of providing care for a patient [35] whereas a variable expense does increase or accrue with incremental patients receiving health care. A direct cost can be either a fixed or variable cost. In the earlier example, the cost of a surgical implant used in a patient’s care is a variable direct cost, while the salary of the operating room nurses who were involved in the patient’s care is a fixed direct cost. In general, the majority of indirect costs in health care are fixed costs.

When seeking to understand the financial impact of a service line for the hospital, the most common measure used is known as the contribution margin. Commonly used variations of this measure include the variable contribution margin and the direct contribution margin. The formulas to calculate these are simple [35]:

variable contribution margin = net revenue (all the revenue the hospital receives for providing care to a population of interest) minus the variable direct expenses for the population of interest

direct contribution margin = net revenue (all the revenue the hospital receives for providing care to a population of interest) minus (variable direct expenses + fixed direct expenses) for the population of interest.

The sum of variable and fixed direct cost reflects the cost of providing the care being evaluated for one additional patient. The goal of these measures of the contribution margin is to understand how much revenue the service line contributes toward the hospital after accounting for the direct costs. In general, these measures of the contribution margin are a more consistent measure of the profitability of the service line. When considering the indirect costs for care to determine profitability, the measure used is referred to as the net margin. While indirect costs are legitimate expenses involved in caring for patients, the allocation of the indirect expenses are often inconsistent across various service lines in a hospital or health system.

In developing a plan to partner with a hospital, there are several things for physicians to consider. The most important consideration when speaking with hospital leadership is to know their lines of business. No one knows the clinical aspects of the practice or service line better than the physicians who deliver that care. To improve their knowledge of their services, physicians should answer the following questions: (1) Is my hospital service line profitable? (2) What are the major drivers of profitability for my service line? (3) What is my average length of stay? (4) What are my patient satisfaction scores? (5) What is the cost of major surgical implants my practice uses? (6) Who is my hospital service line administrator?

To interact with hospital administrators effectively, it is important for physicians to understand their environment, particularly as it impacts hospital operations. To improve their knowledge of their environment, physicians should answer the following questions: (1) Does my hospital have a strategic plan? If it does, have I read it? (2) Does my hospital have a specified mission from a sponsoring organization? (3) Is my hospital profitable? (4) Are my hospital beds full most of the time? (5) Is my hospital a Graduate Medical Education (GME) sponsor? (6) What are my Hospital Compare Scores [30] or other publicly reported data?

Efforts to develop alignments between physicians and hospitals or health systems are typically seeking a form of a win-win relationship. There are multiple methods of partnering or developing alignments between physicians and hospitals. In general, these methods involve some form of fund flow between the two partners. There are multiple vehicles or methods to consider when looking to partner, including medical directorships, contractual arrangements for call pay, medical coverage agreements, comanagement, gain sharing, information technology strategies, joint ventures, support for care of uninsured or underinsured, and employment agreements; this is not an exhaustive list. Before considering any one of these methods, physicians should be sure of the laws influencing these areas and assess their impact [8]. They include the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, which prevents payment to nonemployed providers for referral of Medicare/Medicaid patients to hospitals and clinics [22]; the Stark Law, which prevents payment of providers for referral of Medicare/Medicaid patients to providers of healthcare services with which the physicians have financial relationships [5]; and the “stands in the shoes” rule, which implicates the individual physician for a relationship his or her department or practice may have with a provider of healthcare services [5]. The physician leader must be able to assess his or her knowledge of the service line, as well as his or her own environment, to understand which partnering strategies make the most sense. It can be helpful to visualize this as a 2 × 2 matrix with the headings “service line profitable (yes or no)” and “hospital profitable (yes or no)” (Table 1).

Table 1.

A 2 × 2 matrix detailing potential strategies for orthopaedic surgeon leadership to demonstrate value

| Hospital profitable (indirect costs covered) | Service line profitable | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Yes | Service line management agreements | Cost control through service line management |

| Hospital within a hospital | LOS, implant costs, partner to enhance OR efficiency | |

| Comanagement agreements | Work toward service line management agreements | |

| Grow elective case volumes | Grow elective case volumes | |

| Partner to enhance OR efficiency | Service line resources to reduce LOS | |

| Comply with quality process measures | Comply with quality process measures | |

| No | Service line management agreements | Cost control through service line management |

| Grow elective case volumes | LOS, implant costs, partner to enhance OR efficiency | |

| Partner to enhance OR efficiency | Work toward service line management agreements | |

| Focus on patient satisfaction scores | Focus on patient satisfaction scores | |

| Advocate for hospital service quality | Advocate for hospital service quality | |

| Comply with quality process measures | Comply with quality process measures | |

| Understand indirect cost allocation | ||

OR = operating room; LOS = length of stay.

If the hospital is profitable, the indirect expenses are covered. In this situation, adding procedural volume that has a positive contribution margin to a hospital with unfilled patient bed capacity is of immediate value for the hospital. In the favorable situation where the physicians have a profitable service line, there are opportunities for development of a shared management structure, such as a hospital within a hospital or comanagement structure. Engaging with hospital administration to share in directing marketing efforts and service line growth can be of mutual benefit in this scenario.

Hospitals that are not profitable struggle to cover their indirect costs. In this situation, expense management, identification of operational inefficiencies, and adding surgical volume may be considered in efforts to align. When the service is not profitable, it is important to work with the hospital finance department to understand how indirect expenses are assigned. This may result in apparent poor performance when, in fact, expense assignment is not optimal. Physicians should recognize indirect expenses are legitimate expenses the hospital must pay; similarly, physicians should recognize it is in their interest to ensure these expenses are fairly allocated.

In the recent work of Kaplan and Porter [14], they argue human resources account for a greater portion of expenses but are difficult to measure, thereby leading to underrepresentation in cost-accounting systems. They suggest implementing time-driven activity-based accounting can lead to more accurate cost measurement and effective cost control policies. This issue is particularly relevant for orthopaedic surgeons who use devices with costs that are easily measured, possibly shifting the reporting of the cost structure of the service line away from accurately capturing the human resource expenses. If their service lines continue to be unprofitable, physicians should consider that the hospital may benefit from revising its accounting methodology.

Other Financial Advantages to the Hospital

There are additional financial impacts to hospitals beyond the traditional contribution margins. These result from physicians and hospitals partnering to establish centers of excellence in specific areas. Examples of these include the establishment of activation fees hospitals can charge in trauma centers. Physician practices that have expertise in key specialties such as orthopaedic surgery allow hospitals to qualify as a Level I trauma center [1]. Federal law requires state Medicaid programs make Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments to qualifying hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and uninsured individuals to offset the burden of caring for this relatively underfunded population [20]. These payments to hospitals are made possible by the professional work of providers such as orthopaedic surgeons. However, orthopaedic surgeons, like other providers, are subject to the same underfunded payer mix as the hospitals and often are not able to share in the DSH payments made to the hospitals.

Similarly, physicians should attract patients for a broader range of conditions. Hospitals are able to generate substantially more revenue per admission than the professional revenue generated by treating physicians [32]. Vallier et al. [32] referred to this as the multiplier effect. They reported, for orthopaedic trauma admissions, on average 7.8 times the revenue was collected by the hospital for facility services generated for each dollar collected by the orthopaedic surgeon. However, the hospital bears the majority of the expense in caring for these patients. In the negotiation, an understanding of contribution margins is important to address the overall. Hospitals at times can leverage physicians as medical staff at an academic medical center or employed physician staff in a broad range of specialties to attain improved reimbursement rates from insurance companies that can be at a proportionally higher rate for the hospital than their physician contracts [7]. Physicians should learn from their hospital administrators how contracted rates for hospital and physician reimbursement are being negotiated in their system.

Nonfinancial Value

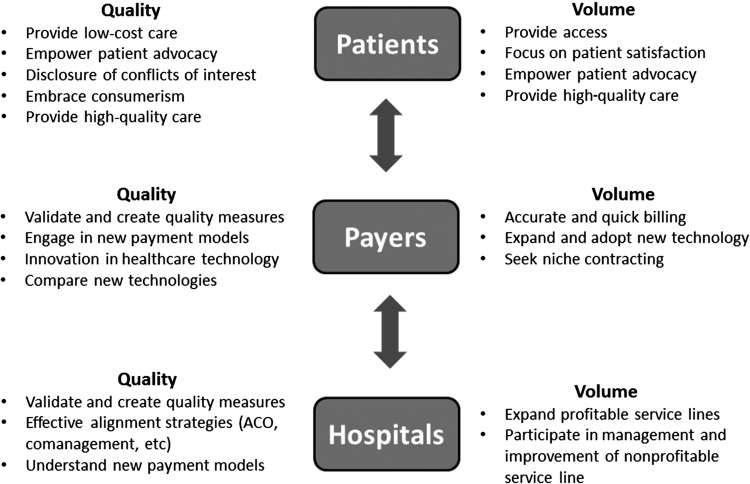

Physicians can bring other strategies to the table to add value to their hospitals or health systems (Fig. 1). The role of the physician as patient advocate leads to a variety of ways to add value to a healthcare system. Physicians should advocate for necessary capital equipment to perform the clinical care required by the patients. For proper care, surgeons should have access to a trauma operating room, adequate operating room time, and where appropriate, medical services agreements. Physicians should ensure efforts of the surgeons and staff given toward providing musculoskeletal care are appropriately recognized and compensated. Physicians should become GME advocates by identifying those rotations for learners in their clinical areas that are more service-oriented than education-oriented and bring these to the attention of the hospital. Physicians should look to their medicine colleagues to identify hospitalist providers or midlevel providers to help provide service coverage.

Fig. 1.

The diagram highlights the aspects of the practice of orthopaedic surgery that create value from the perspective of different stakeholders in healthcare. The quality or value-driven model emphasizes a set of behaviors and incentives for providers to create value in musculoskeletal care different from that of the traditional volume-driven paradigm. Orthopaedic surgeons may need to understand and execute plans to address both of these paradigms in this time of healthcare reform. ACO = Accountable Care Organization.

Physicians should also become advocates for quality and safety in medicine as these are becoming more important for all medical specialties. The Institute of Medicine report To Err Is Human [15] documented the prevalence of errors in the delivery of inpatient care that leads to patient harm. Metrics that reflect substantial and important errors are now increasingly being reported publically. Physicians have an important role to play in improving patient safety. Reducing medical errors can substantially reduce the costs associated with providing care [15].

The combination of high-volume, high-cost, and highly reimbursed care has thrust orthopaedic surgery into the spotlight of hospitals and policymakers. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) [31] has accelerated the quality and transparency movement in the US healthcare system, as well as the transition from a volume-based healthcare system to a value-based purchasing system [6]. This creates new opportunities for physicians to demonstrate and create value for their hospitals. However, these same value-based payment reforms and bundling create new challenges for hospitals, challenges that will be met most effectively through effective physician-hospital alignment. Since quality makes up ½ of the value equation, many reforms are focused on this. Improving quality starts with increasing transparency. Many reforms that are already in place and some that are developing aim to increase the transparency of cost and quality. These include the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, Electronic Health Records, and meaningful use criteria; the tiering of providers based on cost and quality; The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; and the Sunshine Provisions (increased disclosure of potential conflicts).

The quality and safety movement affects hospitals substantially and potentially more than any other provision in the PPACA. Provisions are in place to encourage public knowledge of hospital quality, and patients will choose their hospitals (and subsequently providers) based on reported quality and safety metrics [19, 30]. In addition, payments are likely to be higher to hospitals with higher quality, creating influences from both payers and patients to deliver and demonstrate valuable care [18]. Currently, quality of care is often measured by process measures. These are measurable aspects of patient care, such as the timing of the administration of preoperative antibiotics. Such recommendations are ideally supported by medical evidence with the intent that accurate implementation of the process will lead to improved patient outcomes. Orthopaedic surgeons who can help their hospitals demonstrate quality are seen as valuable by healthcare systems.

Discussion

We discussed ways in which an orthopaedic surgery practice can generate value for a health system or hospital. Orthopaedic surgeons engage in negotiations to advocate for healthcare resources to be directed toward improving patient care. By understanding what hospitals and health systems perceive as value, orthopaedic surgeon leaders will be more effective in engaging in these discussions.

We recognize limitations to our review. First, there is little peer-reviewed literature and little substantive research concerning the topic of this review. The goal of physicians is to provide high-quality, compassionate health care to their patients. Hospitals and health systems can direct resources in a manner to improve patient care. Physicians are the advocate for patient care with these larger organizations. As such, physicians benefit when they can articulate the value they contribute when negotiating for these resources. Second, the perspective of value is also important. It is different for individual patients, employers, payers, and society. Hospitals have a different perspective from that of insurers or society as a whole. While the long-term value of an intervention procedure, such as a THA, may be cost saving to society, payers might not experience these savings due to the transient nature of insurance coverage. In other words, if it takes 10 years to break even on the direct medical cost investment, the insurer will not experience the cost savings, even if society does, from an intervention procedure, such as a THA, if the patient is covered by an insurer for only 5 years. As more integrated provider models develop, such as Accountable Care Organizations, the indirect costs of care may become more relevant to the entire organization. Furthermore, presenting the indirect cost savings physicians and their hospitals provide to employers can direct large groups of patients to their organizations. The third limitation is the tendency to measure processes as surrogates for outcomes; outcomes are often less finite and difficult to measure. An example is the measurement of preoperative antibiotic administration. This is a process measure that aims to improve the outcome of infection and is appropriate for surgeries involving implants, but there is little evidence that antibiotics reduce infection in low-risk cases without implants, such as in many hand and foot surgeries and arthroscopies. Therefore, a process is being measured with physician and hospital resources that may not affect outcomes. Immense value can be created for the hospital by physicians engaging in the quality movement, helping themselves and the patients in the process.

Orthopaedic surgeons should demonstrate leadership in the daily activities of ensuring delivery of quality patient care that is fiscally responsible. Such leadership, coupled with a willingness to engage with hospital administrators to improve the delivery of care, is seen as valuable by healthcare administrators. Orthopaedic surgeons who can bridge the gap between physician practice and hospital operations, to improve patient care, can have a great deal of influence in their environments (Fig. 1). Understanding those aspects of healthcare delivery that impact hospitals and healthcare systems is an important step for developing physician leaders.

The transition in health care from the traditional fee-for-service model, with a focus on surgical outcomes, toward evolving payment models, with incentives for cost reduction, process measures, and patient-specific outcomes, is underway. Grounding in traditional medical finance models and an awareness of the evolving quality movement are necessary for the physician leader of tomorrow. All the challenges of GME and advancing health care through basic and clinical research must be viewed through these evolving perspectives on the delivery of patient care.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

References

- 1.Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient: 2006. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamm EL, Rosenbaum P, Stratford P. Validation of the measure of processes of care for adults: a measure of client-centred care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:302–309. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman K, Knight J. Financial Intellegence: A Manager’s Guide to Know What the Numbers Really Mean. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya T, Freiberg AA, Mehta P, Katz JN, Ferris T. Measuring the report card: the validity of pay-for-performance metrics in orthopedic surgery. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:526–532. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Federal Register, Vol 71, Number 152. 42 CFR Part 411. Medicare program; physicians’ referrals to health care entities with which they have financial relationships; exceptions for certain electronic prescribing and electronic health records arrangements; final rule. 2006. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud-and-Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/downloads/CMS-1303-F.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012. [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital value-based purchasing. 2012. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html. Accessed October 18, 2012.

- 7.Devers KJ, Casalino LP, Rudell LS, Stoddard JJ, Brewster LR, Lake TK. Hospitals’ negotiating leverage with health plans: how and why has it changed? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:419–446. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glaser DM. Legal issues affecting ancillaries and orthopedic practice. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39:89–102, vii. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA, Charns MP. From profession-based leadership to service line management in the Veterans Health Administration: impact on mental health care. Med Care. 2003;41:1013–1023. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000083747.57722.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo KL, Anderson D. The new health care paradigm: roles and competencies of leaders in the service line management approach. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2005;18:suppl xii–xx. [PubMed]

- 11.Harr S, Shireman CW, Jebson RL. Creating and promoting a sports performance service offering. J Med Pract Manage. 2007;22:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haugh R. A joint strategy for orthopedics: hospitals team up with docs to keep a lucrative service line. Hosp Health Netw. 2002;76(54–58):52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain AK, Thompson JM, Kelley SM, Schwartz RW. Fundamentals of service lines and the necessity of physician leaders. Surg Innov. 2006;13:136–144. doi: 10.1177/1553350606291044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan RS, Porter ME. How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2011;89:46–52, 54, 56–61 passim. [PubMed]

- 15.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon B, Tromanhauser SG, Banco RJ. The spine service line: optimizing patient-centered spine care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:S44–S48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lambert CR, Bunker S, Garrison LF, Means MD, Pepine CJ, Conti CR, Dewar MA, Goldfarb T. An academic-community cardiovascular service line affiliation: design, implementation, and performance. Am Heart Hosp J. 2006;4:86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-9215.2006.05570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lansky D, Nwachukwu BU, Bozic KJ. Using financial incentives to improve value in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1027–1037. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marjoua Y, Butler CA, Bozic KJ. Public reporting of cost and quality information in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1017–1026. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mechanic RE. Medicaid’s Disproportionate Share Hospital Program: complex structure, critical payments. National Health Policy Forum Background Paper. 2004. Available at: http://www.nhpf.org/library/background-papers/BP_MedicaidDSH_09-14-04.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

- 21.Navathe AS, Volpp KG, Konetzka RT, Press MJ, Zhu J, Chen W, Lindrooth RC. A longitudinal analysis of the impact of hospital service line profitability on the likelihood of readmission. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:414–431. doi: 10.1177/1077558712441085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Office of the Inspector General. US Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register, Vol 72, Number 192. 42 CFR Part 1001. Medicare and state health care programs: fraud and abuse; safe harbor for federally qualified health centers arrangements under the anti-kickback statute; final rule. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/authorities/docs/07/HealthCenterSafeHarbor.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012. [PubMed]

- 23.Patterson C. Orthopaedic service lines—revisited. Orthop Nurs. 2008;27:12–20. doi: 10.1097/01.NOR.0000310606.55000.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranawat AS, Koenig JH, Thomas AJ, Krna CD, Shapiro LA. Aligning physician and hospital incentives: the approach at hospital for special surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2535–2541. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0982-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saver C. Joint MD-RN team drives results for an orthopedic service line model. OR Manager. 2010;26:1,17–20. [PubMed]

- 26.Soohoo NF, Lieberman JR, Farng E, Park S, Jain S, Ko CY. Perioperative quality-of-care measures for patients undergoing total hip or total knee replacement. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2009;19:249–253. doi: 10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.v19.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sussman I, Prystowsky MB. Pathology service line: a model for accountable care organizations at an academic medical center. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:629–631. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turnipseed WD, Lund DP, Sollenberger D. Product line development: a strategy for clinical success in academic centers. Ann Surg. 2007;246:585–590; discussion 590–582. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Turnipseed WD, Wolff M, Fischer L, Edwards N. Cardiovascular service line development: what is it, who benefits and is it worthwhile? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2007;7:335–341. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services. Hospital compare. 2012. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/. Accessed October 18, 2012.

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health care law and you. 2012. Available at: http://www.healthcare.gov/law/index.html. Accessed October 18, 2012.

- 32.Vallier HA, Patterson BM, Meehan CJ, Lombardo T. Orthopaedic traumatology: the hospital side of the ledger, defining the financial relationship between physicians and hospitals. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:221–226. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31815e92e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams J. A new road map for healthcare business success. Healthc Financ Manage. 2011;65:62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson NA, Ranawat A, Nunley R, Bozic KJ. Executive summary: aligning stakeholder incentives in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2521–2524. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0909-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young DW. Management Accounting in Health Care Organizations. San Franscisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]