Abstract

Ultrasound (US) plays an essential role in the follow-up of operated tendons. The US operator must keep in mind three main elements: healing of traumatic injuries of the tendons seems to follow the biological model of histologic healing, surgical repair of a tendon rupture improves the structural parameters of the operated tendon, but it does not grant restitutio ad integrum, and US findings therefore seem poorly correlated with the functional evolution.

Before examination, the US operator should be familiar with the nature of the tendon injury that has led to surgery including location, severity, time elapsed between tendon injury and surgical repair, surgical technique, postoperative course and possible complications. US findings in operated as well as non-operated tendons depend on several factors: morphology, structure, vascularization of the tendon, mobility of the tendon and mobility of the peritendinous tissues. Particular features are therefore considered according to the location: shoulder, elbow, wrist, hand, knee, ankle and foot. Interpretation of the US image requires knowledge of the surgical technique and "normal" postoperative appearance of the operated tendon in order to detect pathological findings such as thinning, persistent fluid collections within or around the tendon, persistent hypervascularization, intratendinous calcifications and adhesions.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Tendons, Operated Tendons

Sommario

L’ecografia riveste un ruolo essenziale nel follow-up dei tendini operati. Nella sua esecuzione l’ecografista deve tenere ben presenti tre punti: la cicatrizzazione delle lesioni traumatiche dei tendini, all’esame ecografico, sembra seguire il modello biologico di cicatrizzazione istologica, la riparazione chirurgica di una rottura tendinea migliora i parametri strutturali del tendine operato, ma non apporta una restitutio ad integrum, i segni ecografici sembrano mal correlati all’evoluzione funzionale.

Prima di iniziare l’esame l’ecografista deve conoscere alcuni dati: la natura della lesione tendinea per cui è stato realizzato l’intervento chirurgico, la sede, la gravità, l’intervallo temporaneo tra la lesione tendinea e la sua riparazione chirurgica, il tipo di tecnica, il decorso e le eventuali complicanze post-operatorie.

Come per il tendine non operato la semiotica ecografica è basata su vari elementi: morfologia, struttura, vascolarizzazione del tendine, sua mobilità e mobilità dei tessuti peritendinei.

Vengono quindi presi in considerazione problemi particolari a seconda della sede: spalla, gomito, polso e mano, ginocchio, caviglia e piede.

L’interpretazione delle immagini dell’ecografia richiede la conoscenza della tecnica operatoria e dell’aspetto “normale” del tendine operato.

È importante mettere in evidenza i reperti peggiorativi quali: assottigliamento, raccolta liquida intra o peritendea persistente, ipervascularizzazione persistente, calcificazioni intratendinee, aderenze.

Introduction

The main objective of tendon surgery is to restore satisfactory function of the tendon. Indications and surgical techniques vary, and the ultrasound (US) appearance of an operated tendon depends on many factors, which must be known to the US operator before the examination is carried out [1,2]. Postoperative examination has been improved by the recent technological progress, but the follow-up of an operated tendon is primarily clinical, although clinical examination may not be sufficient in the presence of certain complications. As US diagnosis may in some cases lead to repeated surgery, the US operator must formulate his/her conclusions clearly and with great caution.

Some general guidelines on the healing of operated tendons taken from the literature [1,2] may be useful for the interpretation of US findings:

1) At US examination, the healing of traumatic tendon injuries seems to follow the biological model of histologic healing.

2) Surgical repair of a tendon rupture improves the structural parameters of the operated tendon, but surgery does not grant restitutio in integrum.

3) US findings seem to be poorly related to functional evolution.

Operated tendons can be evaluated by two different imaging techniques:

- US because of the dynamic nature of this technique and the contribution of color Doppler US.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because of the contrast resolution; MRI using paramagnetic contrast agent is the examination of choice for evaluating the healing of the tendon [3].

Essential information to be collected before starting the imaging examination

-

1.

Clarify the nature of the tendon injury that led to surgery: rupture, impingement,tenosynovitis, cancer or retinaculum injury.

-

2.

Location and severity of the injury as well as time elapsed between tendon injury and surgical repair.

-

3.

Which surgical technique was used? Tendon scarification, percutaneous sutures, open suture, re-insertion, tenodesis, tenotomy, tenosynovectomy, tendon transposition or transfer?

-

4.

Postoperative course and the characteristics of the prescribed therapy: immobilization or rehabilitation?

-

5.

Possible postoperative complications such as partial or total disruption of normal tendon function or a secondary injury.

US findings

US study should be focused on the following features:

▪ General morphology of the tendon: thickness, width, contours, continuity

▪ Structure: homogeneity, echogenecity

▪ Vascularization: color Doppler US examination

▪ Mobility of the tendon and peritendinous tissues

Thickness and width

The operated tendon is always thicker and/or wider than a normal tendon. This progressive increase in size occurs during the first 3–6 months after surgery and is irreversible. The extent of increase varies according to the surgical technique (tendon scarification is always followed by a substantial increase in volume due to dissociation of the tendon fibers). Healing of the tendon stumps in case of simple end-to-end suture leads to focal thickening called “tendon callus” (Fig. 1a,b). In these cases, a thinned tendon is highly suggestive of re-rupture (Fig. 2).

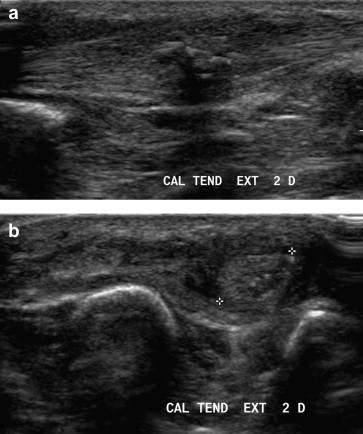

Figure 1.

Tendon callus: longitudinal scan (A) and axial scan (B). US shows focal thickening of the tendon on the surgical site.

Figure 2.

Re-rupture of the patellar tendon. On the surgical site the patellar tendon appears thinned instead of thickened; this is a US sign highly suggestive of re-rupture.

Contours and continuity

Changes in the tendon contours depend on numerous circumstances. A typical example is suture of the Achilles tendon after total rupture [4]. If percutaneous tenotomy is performed, the contours may be irregular even if continuity is preserved (Fig. 3a,b). In these cases US shows a circumferential, hypoechoic, peritendinous area which may persist for up to 3 months (Fig. 4). Surgical treatment of the synovial sheath may be followed by postoperative synovitis during the first months (Fig. 5). Diagnosis of re-rupture of the tendon can be difficult depending on the location of the lesion, time elapsed from surgery and surgical technique.

Figure 3.

Complete rupture of the Achilles tendon. After percutaneous tenotomy, US shows maintained continuity but irregular contours still within normal limits.

Figure 4.

Outcome of percutaneous tenotomy of the Achilles tendon. US image shows a hypoechoic peritendinous area, which may persist for up to 3 months.

Figure 5.

Tenosynovitis after tendon sheath surgery. US shows a hypo-anechoic fluid collection of the sheath surrounding the tendon (A: sagittal scan; B: axial scan).

Internal structure

The following anomalies may be observed independently of the location and operative technique:

-

-

loss of normal fibrillar pattern (Fig. 6)

-

-

a heterogeneous structure is “normal” during the first months after surgery

-

-

small hypoechoic areas surrounding the stitches in the first 6 months after surgery (Fig. 7)

-

-

fluid collections which suggest a poor prognosis when more than 50% of the tendon is affected (Fig. 7)

-

-

intratendinous surgical material (Fig. 8a,b)

-

-

calcifications (Fig. 9a,b)

Figure 6.

Tenotomy of the Achilles tendon. Seven months after surgery US shows loss of normal fibrillar tendon appearance.

Figure 7.

Tenotomy of the Achilles tendon. US shows small hypoechoic areas surrounding the stitches (a characteristic image during the first 6 months) and fluid collection (suggestive of a poor prognosis when more than 50% of the tendon is affected).

Figure 8.

Flexor tendon surgery of the third finger. Postoperative x-ray shows the presence of surgical material (A); US shows that it is intratendinous (B).

Figure 9.

Distal biceps tendon surgery. Postoperative x-ray shows extensive calcifications (A); US shows that they are intratendinous (B).

Intratendinous and peritendineus color Doppler US

-

▪

Right after surgery: no vascularization visible at color Doppler US

-

▪

1 month: intratendinous vascularization can be seen

-

▪

3 months: intratendinous hypervascularization (Fig. 10a)

-

▪

6 months: stabilization and regression; pathological scarring may occur after this moment

-

▪

Changes in peritendinous vascularization are not sufficiently codified (Fig. 10b).

Figure 10.

Color Doppler US evaluation of operated tendons. Three months after surgery the tendons appear constantly hypervascular (A), whereas vascularity of the peritendinous tissue is less constant (B).

Mobility

During the first few months after surgery a physiological reduction of tendon mobility is observed. Diagnostic criteria related to peritendinous adhesion are subjective. Perception of normal sliding of the tendon is difficult to codify, but sliding of the tendon is generally decreased during movement compared to the surrounding structures (tendon sheath, fatty tissue, etc.).

Specific locations

Shoulder

The sutures often involve several tendons, and surgical techniques are varied. Abrasion of the upper bundle of the greater tuberosity is often followed by major changes at the enthesis. The long head of the brachial biceps tendon may be the site of tenodesis or tenotomy, and the rotator cuff interval may not be sutured. Generally postoperative follow-up is carried out to assess the continuity of the tendon, the correct position and thickness of the tendon, if the surgical wire tension is adequate (Fig. 11) and to assess the presence of possible secondary bursitis.

Figure 11.

Reconstruction of the supraspinatus tendon. US shows continuity of the tendon, which is in the correct position, adequate thickness and correct tension of the surgical wires.

Elbow

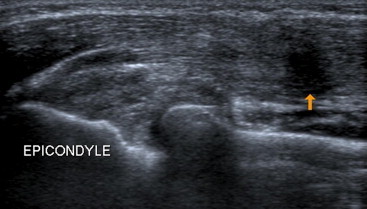

Assessment of the suture in case of distal biceps tendon rupture is difficult. Tendon reattachment is followed by a heterogeneous US appearance of the enthesis with possible local calcification or ossification. Tenotomy of the extensor radialis brevis tendon at the lateral epicondyle is carried out far from the enthesis (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Tenotomy of the common extensor tendon. US shows the localization far from the enthesis (arrows).

Wrist and hand

The three main complications are re-rupture, adhesions and callus lengthening (Fig. 13). Dynamic US examination is very useful, but sometimes interpretation of the image is difficult. In that case MRI should be performed.

Figure 13.

Reconstruction of the long flexor tendon of the thumb. MRI using axial scan (A) and sagittal scan (B) and also US (C) show the presence of callus due to elongation.

Knee

Surgery is usually carried out due to rupture of the quadriceps or patellar tendon. Another indication is treatment of tendinopathy of the patellar tendon (scarification). Abnormal vascularity may occur during rehabilitation showing postoperative tendinopathy (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

Reconstruction of the patellar tendon. US performed during rehabilitation shows thickening of the tendon and loss of normal fibrillar appearance (A). Color Doppler US shows abnormal vascularity due to postsurgical tendinopathy (B).

Ankle and foot

The most frequent complication of tenotomy carried out due to Achilles tendon rupture is posttraumatic re-rupture. US appearance depends on the surgical technique. After open surgery, the tendon always appears thickened and heterogeneous.

Conclusions

Interpretation of US images requires knowledge of the surgical technique and the circumstances of the injury. An operated tendon will never regain a normal appearance. The US operator should be familiar with the "normal" appearance of the operated tendon in order distinguish between normal postsurgical changes and real pathologies.

It is important to pay attention to pathological findings such as:

-

♣

tendon thinning

-

♣

persistent fluid collections within or around the tendon

-

♣

persistent hypervascularity

-

♣

intratendinous calcifications

-

♣

adhesions.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Brasseur J.L., Nicolaon L., Saillant G. Echographie des tendons opérés. In: Bard H., Cotten A., Rodineau J., Saillant G., Railhac J.J., editors. Tendons et enthèses, Monographie du GETROA-GEL, Sauramps. 2003. pp. 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peetrons P., Vanderhofstadt A. Echographie des tendons traités. In: Brasseur J.L., Dion E., Zeitoun-Eiss D., editors. Actualités en échographie de l’appareil locomoteur Sauramps. 2001. pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drapé J.L., Cohen M. Imagerie des complications des tendons opérés. In: Drapé J.L., Blum A., Cyteval C., Pham T., Dautel G., Boutry N., Godefroy Poignet et Main D., editors. Monographie du GETROA-GEL, Sauramps. 2009. pp. 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fantino O., Besse J.L., Moyen B., Tran Minh V.A. Imagerie du tendon calcanéen opéré: Echographie et IRM. In: Bard H., Cotten A., Rodineau J., Saillant G., Railhac J.J., editors. Tendons et enthèses, Monographie du GETROA-GEL, Sauramps. 2003. pp. 395–411. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.