Abstract

To address the requirement for lymphatic capillaries in DC mobilization from skin to lymph nodes, we utilized mice bearing one inactivate allele of VEGFR3 where skin lymphatic capillaries are reported absent. Unexpectedly, DC mobilization from the back skin to draining lymph nodes was similar in magnitude and kinetics to control mice and humoral immunity appeared intact. By contrast, DC migration from body extremities, including ear and forepaws, was ablated. An evaluation in different regions of skin revealed rare patches of lymphatic capillaries only in body trunk areas where migration was intact. That is, whereas the ear skin was totally devoid of lymphatic capillaries, residual capillaries in the back skin were present, though retained only at ~10% normal density. This reduction in density markedly reduced the clearance of soluble tracers, indicating that normal cell migration was spared under conditions when lymphatic transport function was poor. Residual lymphatic capillaries expressed slightly higher levels of CCL21 and migration of skin DCs to lymph nodes remained dependent upon CCR7 in Chy mice. DC migration from the ear could be rescued by the introduction of a limited number of lymphatic capillaries through skin transplantation. Thus, the development of lymphatic capillaries in the skin of body extremities was more severely impacted by a mutant copy of VEGFR3 than trunk skin, but lymphatic transport function was markedly reduced throughout the skin, demonstrating that even under conditions when a marked loss in lymphatic capillary density reduces lymph transport, DC migration from skin to lymph nodes remains normal.

Introduction

Lymphatic vessels mediate clearance of macromolecules and immune cells, such as antigen-transporting dendritic cells (DCs), from peripheral tissues (1–3). Absorptive initial lymphatic capillaries, consisting of a single layer of endothelial cells that form blind-ended termini, are present in most organs (2). These capillaries transition into collecting lymphatic vessels (2) characterized by valves and specialized muscle cells (3). Collecting vessels contact the subcapsular sinus of the regional lymph node (LN) and subsequently drain into efferent vessels and eventually to the thoracic duct, where lymph is returned to venous blood.

Many questions remain unaddressed or unanswered in the nascent field of lymphatic biology. Lymphedematous diseases typically target skin and stem from impaired lymphatic transport (4). However, relatively little analysis has investigated immunological alterations in lymphedema patients, including whether immune cell transport to LNs is severely decreased, as might be expected. Addressing this issue will promote a better understanding of the array of defects that occur in these diseases, including lymphedema associated with breast cancer therapy or filariasis where maintaining immune defense is critical.

DCs enter the lymphatic vasculature through lymphatic capillaries (5–9), gaining access through ‘button-like’ junctions found in initial lymphatic capillaries (10). DCs preferentially seek out areas along lymphatic capillaries that have sparse basement membrane (11, 12). However, the dependence on lymphatic capillaries and the overall density at which lymphatic capillaries must be maintained for DC mobilization to occur has not been formally evaluated.

It is widely assumed that impaired lymphatic transport of macromolecules would be paralleled by impaired immune cell trafficking (13). Here, we studied DC migration from skin to LNs in a mouse model (Chy mice) bearing an inactivating mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of VEGFR3, which is mutated in the form of primary lymphedema called Milroy’s disease (14). Chy mice have a loss of lymphatic transport from skin, reportedly due to a devoid lymphatic capillary network in the skin (15). We illustrate herein that body extremities in Chy mice are indeed devoid of lymphatic capillaries, but body trunk skin retains lymphatic capillaries at approximately 10% normal density. This residual density was insufficient to sustain normal lymphatic transport of macromolecules, but it was remarkably sufficient to permit normal DC migration from skin to LNs. Areas of skin without lymphatic capillaries supported no DC trafficking as expected. Thus, it appears that the lymphatic capillary density needed to sustain normal DC migration to lymph nodes is much lower than the density needed to maintain normal molecular transport.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male Chy (heterozygote) mice on a mixed C3H background, obtained from the Medical Research Council Mammalian Genetics Unit Embryo Bank (Harwell, UK), were crossed with WT littermates to obtain heterozygote Chy offspring. Chy mice were also crossed 10 times with C57BL/6J mates (Jackson Laboratories). Experiments were performed in 6–12 week old Chy mice on both backgrounds and no differences were observed other than a reduced frequency (~10% compared with ~50%) of mutant offspring in the C57BL/6 colony. Differences between sexes were also not observed. The Chy mutation was identified by PCR using 5'-GAAGACCTTGTATGCTAC-3'/5'-AGGCCAAAGTCGCAG-AA-3' primer sequences. CCR7−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, mice expressing enhanced (e)GFP under the control of the β-actin promoter were kindly provided by Miriam Merad (New York, NY), and K14-VEGFR3-Ig (16) were provided to M. A. S. by Kari Alitalo (Helsinki, Finland). Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment and were used in accordance with protocols approved by animal welfare oversight committees at Mount Sinai, EPFL, or Washington University.

FITC painting assay

Epicutaneous application of FITC to study DC migration was performed on the ears and on two areas of each side of the mouse back skin as described (17). Briefly, FITC (8mg/mL) was dissolved in acetone and dibutyl phthalate (Sigma) and applied in 25-µl aliquots. Recovered LNs were teased and digested in 2.68mg/mL collagenase D (Roche) for 25 min at 37°C. Then 100µl of 100mM EDTA was added for 5 min and cells were passed through a 100µm cell strainer, washed, counted, and stained for flow cytometry.

Adoptive transfer of DCs

WT or CCR7−/− bone marrow-derived DCs, generated by culture in GM-CSF supernatant (18), were pulsed overnight with green or red fluorescent polystyrene beads (1-µm diameter; Polysciences) and 4 × 10µl (total 1×106 cells) was injected subcutaneously in the shaved back skin overlying the inguinal LN. Alternatively, spleens from WT or CCR7−/− mice were treated with collagenase D as above. Following red cell lysis, splenic CD11b+ cells were purified by MACS purification (Miltenyi Biotec), labelled with cell tracker orange CMRA (Invitrogen) and transferred at a 1:1 ratio (4 × 10 µl; total 1×106 cells) into shaved back skin overlying the brachial LN. Injections were made using a 26-gauge Hamilton syringe.

Monocyte-derived DC migration

Green or red fluorescent polystyrene beads described above were diluted to 0.1% (wt/vol), and 5µl was injected intradermally into both ears or front footpads, or the shaved back skin, or cheek skin overlying the region of the brachial, inguinal or auricular LN of Chy or WT mice. Three days later, left and right brachial, inguinal, or auricular LNs were respectively pooled from each injected mouse and analyzed by flow cytometry (19).

Lymphatic clearance of dextran

5µl of 1% 70-kDa TRITC-conjugated, lysine-fixable dextran (Molecular Probes) was injected i.d. into ear and back dermis. 5 min. after injection, auricular and brachial LNs were excised and snap-frozen in OCT (Tissue-Tek). To quantify lymphatic transport of dextran, we developed a simple clearance assay and performed it on mice treated to remove hair from ears and back skin one day earlier. 1µl Cy5-Dextran (5,000 kDa; Nanocs) at a concentration of 2mg/ml in sterile PBS was injected via a Hamilton syringe i.d. into the ear, or 5µl of the same tracer at 0.2mg/ml was injected into back skin. Fluorescence was observed through skin using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (M205FA Leica) and images of the skin were acquired each minute for 15 min. using constant exposure time. Fluorescence intensity and exposure times were adjusted to ensure that intensity values were linearly proportional to the actual fluorescence. Images were processed using ImageJ and FiJi software and the rate of clearance was determined by first calculating the area under the curve (AUC) of fluorescence intensity in the injection region at each time point, normalized to the initial value. The normalized rate of fluorescence decay was then calculated from the slope of AUC vs. time. This was considered proportional to the actual rate of Cy5-dextran clearance. Left and right assessments were made at each site (ear or back) in each mouse, and the two normalized values were averaged to generate one mean value per mouse per site.

Flow cytometry

Anti-CD11b, anti-CD11c, anti-CD8α, anti-Ly6G and anti-I-A/I-E mAbs were from BD. Conjugated isotype-matched control mAbs were obtained from eBiosciences or BD. Intracellular staining for CD207 was performed after cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD) for 20 min at 4°C and then washed in Perm/Wash buffer (BD), and incubated for 20 min at 4°C with control goat IgG (R&D Systems) or goat anti-langerin antibody (Santa Cruz) diluted 1:400 in Perm/Wash buffer. Cells were washed twice in Perm/Wash buffer, and incubated with 1:300 anti-goat FITC antibody (Invitrogen) diluted in Perm/Wash buffer for 20 min at 4°C.

Immunohistochemistry

10µm cross-sections of WT/Chy back skin and LNs were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min., stained with primary antibodies for 30 min. and secondary Ab for 30 min., or sections were stained with Hema-3 solution (Fisher). For whole mount staining, ears were dissected, hair was chemically removed and the ear was split into dorsal and ventral sheets. Excess fat and cartilage was removed under a dissection microscope and the tissue was incubated in 0.5M ammonium thiocyanate in H2O for 20 min. before the epidermis was peeled off. The ears were then fixed in 100% acetone for 5 min., followed by 80% methanol for 5 min. before blocking. For the GFP transplant experiments, ears were fixed in 1% PFA / 20% sucrose (Fisher) for 1 h. to preserve GFP signal. Both ears and 60-µm en face frozen sections of back skin were blocked overnight, incubated with primary antibody overnight, and then secondary antibody for 2 h. Primary antibodies were anti-mouse podoplanin (Angiobio), goat anti-CCL21 (R&D Systems), rabbit anti-LYVE-1 (Abcam), anti-smooth muscle actin (Sigma), rabbit anti-collagen IV (Abcam), rat anti-VE-Cadherin (BD), anti-langerin, anti-CD3 and anti-B220 (BD). These were detected with AMCA, Cy2, Cy3 or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Tissue was imaged by confocal microscopy using a Leica SP5 DM, and 3D reconstructions and isosurface rendering were performed using Volocity software.

Quantification of lymphatic capillary density and CCL21 intensity

Thick sections of frozen back skin overlying the brachial LN were stained as above with anti-LYVE-1 and anti-CCL21. Using Volocity software, CCL21+ tissue maps were generated based on signal intensity, and the total area of CCL21+ vessel coverage was quantified. 10 regions were imaged per animal and the mean of these readings was taken as the value for 1 animal, and 8 animals per group. For local density, only the mean of regions of Chy mice that contained any lymphatic capillaries were included and compared with WT mice where all regions contained vessels. CCL21 intensity was measured using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda MD) and reported as mean normalized fluorescence intensity of CCL21+ lymphatic endothelial cells. Measurements were taken from 3 mice/group.

Inflammation and immunization

To induce inflammation, 1µL emulsified CFA (diluted 1:1 in PBS; Sigma) was injected into the right ear dermis of WT and Chy mice using a Hamilton syringe. In the left ear of the same animals, 1µL PBS was injected as a control. Ear thickness was measured using Absolute Digimatic callipers (Mitutoyo). For immunization, 4µg OVA mixed with 25µg Ultrapure 0111:B4 LPS (InvivoGen, Nunningen, Switzerland) or 50µg OVA in emulsified CFA (diluted 1:1) was injected into the back skin dermis of Chy and littermate WT mice. 14–21 days later, serum was harvested and assessed for total anti-OVA IgG antibody by ELISA as previously described (20). Fold-increase in reactivity (optical density, OD) was normalized by dividing the OD value from various dilutions of plasma from the immunized mouse by the OD reading in the non-immunized state.

Skin digestion for flow cytometry

4 hours after injection of emulsified CFA into the ear or back skin dermis, the skin was excised and cut into small segments using scissors. This was then incubated in digestion solution (Liberase (1.75mg/mL) and 2% FCS in RPMI-1640) for 25 min at 37°C.

Skin transplantation model

Mice were anesthetized and the ear skin was cleaned. In the donor animal, a 0.25cm incision was made in the dorsal side of the ear, and a small region of skin was removed. After an identical area of ear skin was removed from the recipient mice, the donor skin was sutured, using 9-0 polyamide monofilament sutures, onto the recipient ear. This was conducted on both ears of the same animal. As a control for the procedure, a “sham surgery” group of mice had an incision made on both ears. After a period of 14 days, 1µm microspheres were injected into the ear dermis adjacent to the transplant and the mice were sacrificed 3 days later. To assess lymphatic capillary density, 5 regions (1 within the transplant site) of the ear were imaged per animal and the mean of these readings was taken as the value for 1 animal.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made by using the Student's t-test. One-way ANOVAs were used for multiple comparisons, with a Tukey post-test. The non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test was used to analyze the aggregate data in the humoral immune response, and a two-way ANOVA was used for repeated measures in the footpad swelling experiments. All experiments contained three or more replicate mice per experimental parameter.

Results

Normal proportions of lymph-trafficking DCs in some lymph nodes of Chy mice

Skin-draining LNs, particularly the inguinal LN, of Chy mice exhibited reduced cellularity compared to WT littermates (Fig. 1A), and the popliteal LN, draining the footpad which had the most overt lymphedema (15), could not be found in most Chy mice. CD11chi LN DC subsets can be broadly divided into “resident” and “lymph-migratory” DCs based on the expression of higher levels of MHC-II on the latter (21). LN-resident DC subsets arrive to LNs through high endothelial venules (22), rather than lymphatics (23). Such resident DCs were present in normal proportions in all Chy LNs examined, including the auricular (which drains the ear), brachial (which drains the upper back skin and front paws) and inguinal (which drains the lower back and belly skin) LNs of Chy mice (data not shown). Unexpectedly, the proportions and numbers of lymph-migratory MHC-IIhi DCs were also similar between WT and Chy mice in the brachial and inguinal LNs draining the trunk skin (Fig. 1B and data not shown), but their frequency was reduced in the ear-draining auricular LN (Fig. 1B). As a distinct approach to identifying lymph migratory DCs, we also analyzed LNs for the frequency of CD207 (Langerin)+ DCs. CD207 is expressed only on lymph-migratory DCs, including epidermal Langerhans cells and CD207+ dermal DCs (24–26). CD207+ DCs were present in all T cell zones of skin-draining Chy LNs (Fig. 1C). As for MHC-IIhi DCs, proportions and numbers of CD207+ DCs were reduced in the auricular LN of Chy mice relative to WT littermates, but were similar in the brachial and inguinal LNs (Fig. 1B, D–E and data not shown). However, CD207 can be expressed by CD8α+ DCs (27), which may be LN-resident DCs, and thus we assessed CD8α expression by this population. Here, we found that all CD207+ DCs expressed CD8α in both genotypes (Figure 1F), however the majority of CD8α+ DCs (60–80%) failed to express CD207 (data not shown). Further, as DCs constitute a minor proportion of the LN cellularity, we examined whether the reduced cellularity of Chy LNs reflected a reduction in numbers of other cell types. Thus, we assessed the total number of B and T lymphocytes in skin-draining LNs in Chy mice, shown in Table 1. Here we found that the numbers of all subsets of lymphocytes, including B cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, were reduced in Chy mice. These results starkly contrasted with findings that MHC-IIhi and CD207+ lymph migratory DCs are completely absent from all skin-draining LNs in K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice (20) (Fig. 1G), which like Chy mice have been reported to lack lymphatic capillaries in skin and exhibit reduced LN cellularity (16). Thus, against our expectations, lymph migratory DCs were not absent in any Chy LNs and were capable of normally populating several Chy LNs.

Fig. 1. Normal proportions of lymph-trafficking DCs in some lymph nodes of Chy mice.

(A) Total cellularity was measured in the auricular, brachial and inguinal LNs of WT and Chy mice. (B) LN preparations from WT and Chy mice were analyzed for CD11c and MHC-II expression and the proportion of CD11c+MHC-IIhi cells are shown. n=6–7 mice. (C) Immunofluorescence images of LNs stained for CD207 (green), CD3 (red), B220 (pink) and LYVE-1 (blue). Bar=12µm. (D) Representative dot plots (D) and proportion (E) of CD207 expression by CD11c+ cells in skin-draining LNs. (F) CD8α expression among CD11c+CD207+ cells in brachial LNs of Chy and WT mice. (G) Proportion of CD11c+MHC-IIhi DCs from pooled brachial, inguinal and axillary LNs from WT and K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice. Open circles, WT mice; closed circles, Chy or K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice. Each circle shows one mouse. n=3–7 mice. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ns=not significant. Results are from at least 3 independent experiments.

Table 1.

Numbers of different immune cell populations in skin-draining lymph nodes of Chy mice

| Auricular LN | Brachial LN | Inguinal LN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | CHY | WT | CHY | WT | CHY | |

| CD4+ T cells | 902±191.8 | 400±31.3 | 538±78.5 | 318±177.3 | 394±32.8 | 75±24.3 |

| CD8+ T cells | 946±126.0 | 406±83.0 | 595±125.2 | 271±114.4 | 423±69.7 | 79±26.6 |

| B cells | 1512±391.4 | 838±202.5 | 711±152.2 | 580±295.8 | 536±110.6 | 212±88.1 |

| Migratory CD207+ DCs | 4.3±0.1 | 0.9±0.3 | 4.7±1.1 | 2.4±1.2 | 4.0±1.4 | 1.5±0.3 |

| Migratory CD207− DCs | 10.4±3.0 | 3.8±1.0 | 8.9±2.3 | 5.4±2.5 | 6.6±2.3 | 2.0±0.7 |

| Lymph node-resident DCs | 63.8±6.0 | 32.5±7.7 | 75.3±7.0 | 46.0±7.3 | 65.2±11.1 | 19.0±3.8 |

Skin-draining auricular, brachial and inguinal lymph nodes from Chy and WT mice were examined for the presence of CD4+ T cells (CD4+), CD8+ T cells (CD8+), B cells (B220+), migratory CD11c+CD207+ DCs, migratory CD11c+CD207− DCs (MHChi but CD207−) and lymph node-resident DCs (CD11c+MHClow−intermediate). Numbers (103) α SEM are shown. Data are from 2 independent experiments.

No kinetic delay in DC migration to lymph nodes in Chy mice

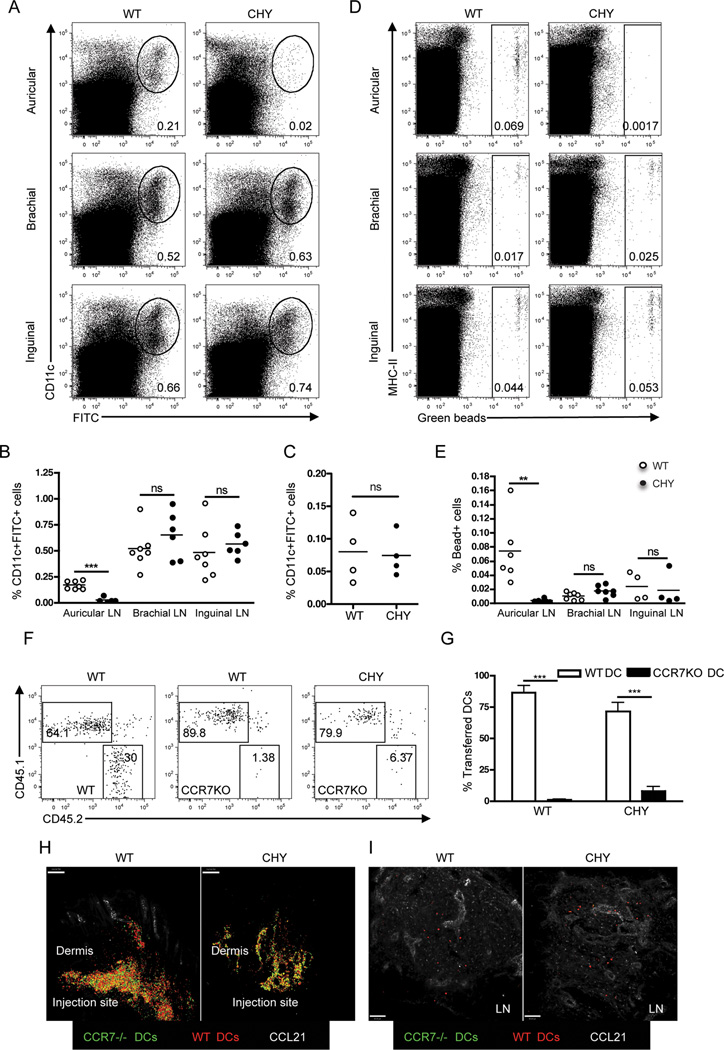

Although lymph migratory DC frequency in Chy LNs was normal in resting LNs draining the back skin, it remained possible that migration of DCs to Chy LNs was slower than under normal conditions. Thus, we set out to quantify DC migration from skin to draining LNs and assess its kinetics in Chy mice. We utilized the established “FITC painting” assay that allows for robust assessment of DC migration with known kinetics. Peak accumulation of FITC+ DCs in LNs occurs at 18 h, with DC arrival just getting underway at 12 h (17, 28). At 18 h after painting the back skin and ear, accumulation of FITC+ DCs was nearly abrogated in the ear-draining auricular LNs of Chy mice, but surprisingly, similar proportions of DCs appeared in brachial and inguinal LNs of Chy and WT mice (Fig. 2A–B). The total number of migrated DCs in the inguinal, but not brachial, LN was reduced in Chy mice (data not shown), reflecting our findings that several LNs were reduced in overall cellularity (Figure 1A) and that DC migration to LNs from lymphatics is typically maintained in a manner proportional to LN cellularity (29).

Fig. 2. No kinetic delay in DC migration to lymph nodes in Chy mice.

(A) Representative dot plots of FITC+CD11c+ cells in skin-draining LNs of WT and Chy mice 18 h after FITC application to the dorsal ear and upper and lower back skin. (B) Percentage of CD11c+FITC+ cells in LNs of WT and Chy mice. n=5–7. (C) Percentage of CD11c+FITC+ cells in brachial LNs of WT and Chy mice 12 h after FITC application to upper back skin. (D) Representative dot plots of MHC-II+ bead+ cells in skin-draining LNs of WT and Chy mice 3 days after i.d. injection of 1µm green fluorescent beads in the ear and back skin. (E) Percentage of green bead+ cells in LNs of WT and Chy mice. Open circles, WT mice; closed circles, Chy mice. n=4–7. (F) Spleen CD11b+ cells from CD45.1 WT and CD45.2 WT (left) or CD45.2 CCR7−/− (middle, right) mice were labelled with CMRA and mixed at 1:1 ratio, then injected into the upper back skin dermis of WT/Chy CD45.2+ mice. At 18 h, CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression was examined in brachial LNs on total CMRA+ cells (F). (G) Results are shown as the mean percentage ± SD of CMRA+ cells that were CD45.1+ vs. CD45.2+ in WT and Chy brachial LNs. (H) WT (red) and CCR7−/− (green) BM-DCs were pulsed overnight with 1µm beads, stimulated with 100ng/mL LPS for 5 h, and injected subcutaneously in the back skin over the inguinal LN. At 16h, inguinal skin and LNs were collected and the migration of bead-labelled cells towards CCL21+ (white) lymphatic capillary-rich dermis was examined (H). (I) Images of the draining inguinal LN in both WT and Chy mice 16 h after injection of bead+ DCs. Bar=80µm. n=4. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ns=not significant. Results derive from 2–4 independent experiments.

Even at 12 h after FITC application, the time of earliest appearance of FITC+ DCs in LNs, no significant differences existed between Chy and WT mice (Fig. 2C). In a second migration assay, we quantified the mobilization of monocyte-derived DCs from skin to LNs in Chy mice by assessing their transport of intradermally injected, 1µm fluorescent beads (19, 30). Intradermal 1µm beads do not freely flow to the LN but are carried there by CD11cloCD11bhi MHC-IIhi DCs (19). Three days after bead injection i.d., bead+ DCs were absent in the auricular LN of Chy mice, but similar proportions and numbers of bead+ DCs were found in brachial and inguinal LNs of Chy and WT mice (Fig. 2D–E and data not shown), as seen after FITC skin painting. Thus, DC mobilization to draining LNs appeared to be normal in Chy mice in a highly region-dependent manner.

Surprised to detect migration of DCs to trunk skin-draining LNs, we explored whether DC migration in Chy mice involved CCR7, the master regulator of DC migration to and within WT LNs (21, 31, 32). We thus competed CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ CCR7−/− splenic CD11b+ cells, labelled with cell tracker orange (CMRA), after they were co-transferred i.d. into the back skin of CD45.2+ WT or CD45.2+ Chy mice. Gating on CMRA+ transferred cells in the brachial LN revealed that donor cells were exclusively derived from WT mice, demonstrating DC mobilization in Chy mice is CCR7-dependent (Fig. 2F+G). To confirm this result, we labelled WT and CCR7−/− DCs with respectively different colored beads, injected them subcutaneously, and assessed their migration. Although migration from the subcutaneous injection site up toward the dermis occurred independently of CCR7 in both genotypes (Fig. 2H), only WT DCs progressed to the LN (Fig. 2I). Thus, using 3 different assays that examined endogenous and adoptively transferred DCs, we conclude that DC migration is kinetically normal and dependent upon CCR7 from the back skin of Chy mice. From the ear, however, DC migration is abrogated.

Regionalized lymphatic defects dictate DC mobilization

Given that some lymph-migratory DCs still populated steady state auricular LNs of Chy mice (Fig. 1C–E) but migration of DCs from the ear that drains to this LN was ablated (Fig. 2B+E), the origin of these DCs in the auricular LN was unclear. Thus, we addressed whether the auricular LN drained other sites that may have intact lymphatic transit of DCs. To this end, we compared endogenous DC migration to the auricular LN from the ear and cheek skin sites simultaneously using green and red beads respectively deposited i.d. in the ear or cheek. We found both ear and cheek bead-transporting DCs in WT littermate auricular LNs, but only cheek-derived bead+ DCs in the auricular LNs of Chy mice (Fig. 3A–B). We then carried out a similar approach to examine DC migration from the forepaw extremities. Here, we injected the two differently colored beads respectively in the back skin or front footpad and assessed the brachial LN for migratory bead+ DCs. Bead+ DCs derived from both peripheral sites were observed in WT LNs, however, only DCs derived from the back skin and not the front footpad were observed in Chy mouse brachial LNs (Fig. 3C–D). Thus, profound defects in DC migration in Chy mice are confined to regionalized areas, notably the body’s extremities, limbs and ears, but migration remains intact when DCs originate from the body trunk and facial skin.

Fig. 3. Regionalized lymphatic defects dictate DC mobilization.

(A) Representative dot plots of cells in the draining auricular LN 3 days after injection of red beads into the cheek skin dermis and green beads into the ear dermis. (B) Percentage of red bead+ cells (cheek skin) and green bead+ cells (ear) in the auricular LN. (C) Representative dot plots of red bead+ and green bead+ cells in the draining brachial LN 3 days after injection of red beads into the upper back skin dermis and green beads into the front footpad dermis. (D) Percentage of red bead+ cells (back skin) and green bead+ cells (footpad) in the brachial LN. Open circles, WT mice; closed circles, Chy mice. n=10–11; ***p<0.001; ns=not significant. Results depict 3 independent experiments.

Rare lymphatic capillaries exist in the back skin dermis of Chy mice

We next analyzed distinct anatomical regions for lymphatic capillaries by microscopy. As macrophages can also express lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1 (LYVE-1), tissues stained for LYVE-1 (Fig. 4A+B) were co-stained with podoplanin, CCL21 and / or Prox-1 to identify lymphatic capillaries (Fig. 4C, D and data not shown). Indeed, LYVE-1+ lymphatic capillaries were completely absent in the ear dermis (Fig. 4A), as reported (15). LYVE-1+ lymphatic capillaries were also not seen in the back skin dermis of Chy mice by cross-section (Fig. 4B), where the sub-adipose layer was markedly thinned (Fig. S1A). However, all Chy skin-draining LNs examined contained LYVE-1+ terminal lymphatic capillaries (1) (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 4. Rare lymphatic capillaries exist in the back skin dermis of Chy mice.

(A) Whole mount staining of ear dermis with LYVE-1 (green) and smooth muscle actin (SMA; red). Bar=60µm. (B) 10µm cross-sections of back skin from WT and Chy mice stained for LYVE-1 (green) and SMA (red). Bar=60µm. (C) Podoplanin (green), LYVE-1 (white) and SMA (red) staining of en face sections of back skin from WT (left) and Chy (middle and right) mice. Bar=150µm. (D) CCL21 staining of lymphatic capillaries in back skin sections from WT and Chy mice. Bar=150µm. (E) Quantification of lymphatic capillary density. (F) Local density of lymphatic capillaries examining only the areas of Chy back skin that contained vessels. Results are from 8 mice/group. (G) Normalized mean fluorescence intensity of CCL21 staining. Measurements were taken from 3 mice/group. (H–I) Whole mount images of the ear dermis (H) and en face images of back skin dermis (I) of WT and Chy mice show podoplanin (green), LYVE-1 (white) and SMA (red) staining. Bar=32µm (H) and 38 (I) µm. Note that pre-collectors are podoplanin+LYVE-1− and exhibit partial SMA coverage. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

In thick en face sheets of back skin or whole-mount preparations of ear dermis that allowed a larger region to be analyzed, uniform lymphatic capillary networks were observed in WT mice (Fig. 4C, left panel). Most regions of back skin in Chy mice were devoid of lymphatic capillaries (Fig. 4C, middle panel), and in the ear entirely, but sparse clusters were present in back skin (Fig. 4C, right panel). These vessels still expressed the CCR7 ligand, CCL21 (Fig. 4D), as in WT mice (12). Quantification of lymphatic capillary density revealed a ~90% reduction in density in Chy dermis (Fig. 4E). Even in scattered clusters of lymphatic vessels, the local density was reduced by ~60% compared with WT (Fig. 4F). CCL21 intensity was modestly elevated in Chy mice (Fig. 4G). Thus, regions of skin in Chy mice that support migration of skin DCs contain very rare networks of lymphatic capillaries, whereas the regions of skin containing no lymphatic capillaries allow no transit of DCs from skin. We also examined lymphatic pre-collecting/collecting vessels, which are characterized by smooth muscle coverage and little or no LYVE-1 expression (33). By whole mount imaging, we observed podoplanin+ LYVE-1− smooth muscle actin (SMA)+ collecting vessels in the ear and back skin dermis of both WT and Chy mice (Figure 4H+I). These collectors were less frequent in the ear and back skin dermis of Chy mice and most appeared blind-ended without connection to LYVE-1+ capillaries (data not shown).

Molecular transport from back skin lymphatic vessels of Chy mice is impaired

The observation that DC migration was normal under conditions of severe lymphatic hypoplasia led us to wonder whether the rare lymphatic vessels in Chy mice had developed compensatory mechanisms to restore transport function in general. However, button-like junctions and portals appeared normal (Fig. 5A–D), suggesting no major compensatory changes at this level. Qualitatively, soluble TRITC-dextran transport from the ear was ablated in Chy mice, but still occurred from the back skin (Fig. 5E+F). To quantify transport of macromolecules from the skin, we injected Cy5-dextran into ear or back skin and monitored its clearance over time at the same sites from which we earlier injected DCs. The median normalized rate of clearance was more profoundly impaired from the ear than from the back skin (Fig. 5G), but transport from the back skin was nonetheless less than half the rate observed in WT littermates (Fig. 5G). Thus, Chy lymphatic vessels do not develop a fully sufficient compensatory mechanism at the level of macromolecular transport to overcome severe lymphatic hypoplasia.

Fig. 5. Molecular transport from back skin lymphatic vessels of Chy mice is impaired.

(A–B) Images show staining with LYVE-1 (green) and VE-Cadherin (red) on lymphatic capillaries in the back skin dermis of WT and Chy mice. Bar=24µm. (B) Enlargement of inset in (A) showing that the structural pattern is highlighted more clearly after isosurface rendering of the image. Unit=5.2µm (left) and 5.08µm (right). (C) Images show staining of back skin lymphatic capillaries with collagen IV (white) and CCL21 (red) in WT and Chy mice. Bar=24µm. (D) Enlargement of inset in (C). Yellow arrowheads indicate lymphatic portals. Bar=11.1µm (left) and 12µm (right). (E–F) Sections of auricular (E) and brachial (F) LNs 5 min. after injection of 50µg TRITC-dextran (red) into the ear and back i.d. Counterstained with DAPI (blue). Bar=60 µm. (G) Lymphatic transport measured in the ear and back skin. Each symbol represents pooled left and right data from a single mouse, and the bar shows the median normalized rate of fluorescence decay. **p<0.01, assessed using a one-tailed Student’s t-test. Measurements are from 1–4 mice/group in 2 independent experiments.

Classical inflammation drives limited lymphangiogenesis but fails to rescue DC mobilization in Chy mice

Since excess levels of VEGF-C can rescue the loss of lymphatic capillaries in the ear of Chy mice (15), and VEGF-C levels are increased during inflammation (34, 35), we assessed whether a classical inflammatory stimulus could induce lymphangiogenesis and DC migration in mutant mice by injection of a small volume of complete freund’s adjuvant (CFA) into the ear dermis. CFA is upstream of lymphangiogenesis around LNs and enhances DC migration (29, 36). We first assessed whether inflammatory cell recruitment to inflamed ear or back skin occurred normally in Chy mice and found that, 4 hours after CFA injection, neutrophils could be found in similar proportions and numbers to WT mice in both sites (Figure 6A+B and S2A+B). Neutrophils can also enter afferent lymph and arrive in LNs rapidly (37), though other neutrophils may arrive through HEVs. When we assessed the accumulation of neutrophils in the brachial and auricular LNs at 4 hours, the frequency of neutrophils in both skin-draining LNs was similar to WT mice (Figure S2C–F), suggesting that neutrophil migration in response to an inflammatory stimulus was intact.

Figure 6. Classical inflammation drives limited lymphangiogenesis but fails to rescue DC mobilization in Chy mice.

(A–B) 4 hr after PBS (white bars) or CFA (black bars) injection in the ear (A) or back skin (B), skin was digested and the total number of live CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils are shown. (C) Graph depicts ear thickness of WT and Chy mice after injection of PBS or CFA into the ear dermis. (D) Plot shows the total cellularity of the draining auricular LN 18 days after CFA treatment. (E) Plot depicts the area of the ear dermis covered by LYVE-1+ vessels 18 days after injection of PBS or CFA. (F–G) Results shown are the proportion (F) and total number (G) of green bead+ cells present in the auricular LN of WT and Chy mice injected with green fluorescent beads on day 15 post-injection with PBS or CFA. LNs were harvested 3 days after injection of green beads. Open circles indicate WT mice while closed circles depict Chy mutant mice. Each circle represents one mouse. (H–I) 4µg OVA mixed with 25µg Ultrapure 0111:B4 LPS (InvivoGen, Nunningen, Switzerland) or 50µg OVA in emulsified CFA (diluted 1:1) was injected into the footpad (H) or back skin dermis (I) of Chy and littermate WT mice. 14–21 days later, serum was harvested and assessed for total anti-OVA IgG antibody by ELISA. Results show the OD value of plasma at various dilutions. n=7–10. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p=0.001; ns=not significant. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Following CFA administration, we observed tissue edema in the ear in both genotypes as expected. However, this inflammation was notably increased and resolved more slowly in Chy mice (Figure 6C). Moreover, the expected lymphadenopathy that occurs in WT mice treated with CFA (29) failed to occur in draining auricular LNs of Chy mice (Figure 6D), and this was similar in the brachial LN after CFA injection in the back skin (data not shown). Lymphatic density was increased in the ears of WT mice treated with CFA but this failed to reach significance (Figure 6E). Despite the strong inflammatory response, there was a significant but minor increase in lymphatic density in Chy mutant mice, with some isolated vessels present in the ears of some mice (Figure 6E and data not shown). However, DC mobilization from the ear remained abrogated in Chy mice 15 days after CFA administration (Figure 6F–G). Thus, induction of general inflammation by CFA injection is not sufficient to promote restorative lymphangiogenesis in regions of Chy mouse skin that are devoid of lymphatics.

Humoral immunity is diminished in K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice following dermal immunization were DC migration in entirely abolished (20). When Chy and WT littermates were immunized with ovalbumin (OVA) mixed with LPS or CFA in the back skin dermis or the footpad and assessed for anti-OVA IgG antibodies in the serum 14–21 days later, footpad immunizations where there are no lymphatic vessels led to abrogated induction of anti-OVA IgG (Figure 6H). However, there was no significant difference in anti-OVA IgG generated from immunizing Chy mice in the back skin relative to WT littermates (Figure 6I).

DC mobilization from regions with no previous drainage can be rescued by skin transplantation

Finally, we assessed whether we could rescue DC mobilization from the most severely affected regions by directly introducing a limited number of lymphatic capillaries. Specifically, we attempted to introduce lymphatic capillaries by transplantation of a small region of WT (or Chy as a negative control) ear skin onto the ear of Chy mice (Figure 7A). We waited 14 days and then assessed lymphatic density and DC mobilization. Lymphangiogenesis was induced in the ear even in regions beyond the transplant area (regions 2–5 in Figure 7A, 7B), and to a limited degree in a proportion of Chy recipients that received Chy mutant donor skin (Figure 7C and data not shown). However, the density of lymphatic capillaries in transplant recipients of WT donor skin was still less than half the density observed in un-manipulated WT mice (Figure 7C). The superior lymphangiogenesis in Chy mice transplanted with WT skin indicated that the donor vessels expand rather than the surgery driving endogenous lymphatic expansion. However to assess this directly, we transplanted dorsal ear skin from β-actin-eGFP mice onto Chy recipients and assessed the lymphatic network for host versus donor origin 2 weeks later. Here we found that the majority (61%) of the LYVE-1+ capillaries, both within and outside the transplanted region, were of donor origin (Figure 7D, G and data not shown). However, we could observe a lower number (24%) of recipient eGFP− LYVE-1+ vessels (Figure 7E, G) and some vessels that appeared to be derived from both donor and recipient endothelium (15%) (Figure 7F, G). However as the donor is not a lymphatic-specific reporter, it remains possible that the few GFP+ cells in Figure 7F are not lymphatic endothelial cells.

Figure 7. DC mobilization from regions with no previous drainage can be rescued by skin transplantation.

(A) Representative photo after WT (or Chy) dorsal ear skin was transplanted onto the dorsal ear dermis of Chy recipient mice. 5 regions (as indicated) were examined for the presence of LYVE+ lymphatic capillaries. (B) Representative LYVE-1 (green) and SMA (red) staining of ear dermis within (left panel; Region 1) and outside (right panel; Region 4) the transplanted region from Chy mice transplanted with WT donor skin. (C) Lymphangiogenesis was assessed 17 days after surgery using Volocity software and the area of ear dermis covered by LYVE-1+ vessels was measured in unmanipulated WT and Chy mice, Chy recipients of WT and Chy donor skin, and mice undergoing sham surgery. n=3–19. (D–F) Representative images of ear dermis of Chy recipients of β-actin-eGFP donor skin 2 weeks post-transplant. Images show LYVE-1 (red; left panel), eGFP signal (green; middle panel) and the colors merged (right panel). Note the presence of LYVE-1+ vessels which are GFP+ (D), GFP− (E) and a mix of the two (F). Bar= 28µm (D), 80µm (E), 37µm (F). (G) LYVE-1+ vessels present in the recipient ear dermis were assessed for GFP signal, quantified and the percentage of vessels in each group are shown. (H) Representative dot plot of MHC-II+ green bead+ cells in the auricular LN of Chy recipients of WT donor skin 3 days after i.d. injection of 1µm green fluorescent beads into the ear. Beads were injected 14 days post-transplant. (I–J) Results shown are the proportion (I) and total number (J) of green bead+ cells present in the auricular LN of transplant recipients or mice undergoing sham surgery. Each circle represents one individual transplant and 2 transplants per mouse were performed. n=11–17. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments.

By intradermally injecting beads adjacent to the transplanted region, we assessed DC migration following skin transplantation or a sham operation (Fig. 7H–J). WT skin transplanted onto Chy recipients increased migration significantly over mice transplanted with mutant skin and sham-operated mice (Fig. 7I, J), and indeed, when we compared transplant or sham transplant data to the migration observed in Fig. 2, we found that transplant of WT onto Chy mice restored migration significantly enough that the difference to unmanipulated WT mice was no longer observable. However, migration in the sham-operated mice or recipients of Chy donor skin remained significantly reduced relative to that in WT mice. Although even transplantation of Chy skin onto Chy mice appeared to restore migration and induce lymphangiogenesis in some mice, WT skin used in the transplant was more often effective. Indeed, if we defined restoration of migration as migration that was quantitatively within one standard deviation of the mean DC migration in unmanipulated WT mice, WT skin transplanted onto Chy mice rescued migration robustly in 64.7% of the recipients, whereas Chy skin transplanted onto Chy mouse ears did so only 21.4% of the time, and sham was minimal at 9.1% (data not shown). To ensure that the VEGFR3 mutation had no effects other than on the formation of initial lymphatic capillaries, we transplanted Chy skin onto WT recipients. Here we found that both lymphatic density and DC mobilization were comparable to unmanipulated WT mice (data not shown). Together these data indicate that transplantation effectively restores DC migration.

Discussion

As anticipated, our data suggest that the presence of lymphatic capillaries in skin is essential for skin DC mobilization to LNs. However, contrary to expectations, even rare, sparsely localized lymphatic capillaries can be sufficient to support DC mobilization without obvious kinetic delay or reduction in magnitude. Steady state migration of lymph-trafficking MHC-IIhi or CD207+ DCs from the back skin, but not the ear, in Chy mice was similar to WT mice. However, CD207 can be expressed by CD8α+ DCs (27), which may be LN-resident DCs seeding the LN through HEVs. We found that all CD207+ DCs expressed CD8α in both genotypes (Figure 1F), however the majority of CD8α+ DCs (60–80%) failed to express CD207. These data suggest that CD8α+CD207− DCs are the LN-resident DCs that enter LNs as precursors through HEVs (22), whereas CD207+CD8α+ DCs likely correspond with lymph migratory DCs. Indeed CD8α expression by lymph migratory DCs has recently been demonstrated in the mesenteric afferent lymphatics (38). Furthermore, migration of DCs after contact sensitization and migration of monocyte-derived DCs was also identical to WT mice from the back skin.

The major difference between skin of the extremities versus that of the body trunk was the presence of rare lymphatic capillaries in the trunk skin compared with their complete absence in extremities such as the ear. There were no obvious differences in button-like junctions (Fig. 5A+B) or portals (Fig. 5C+D) of residual lymphatic capillaries in Chy mice, but these vessels displayed slightly more CCL21. While this increase may augment DC migration in the face of lymphatic hypoplasia, the increase may be too modest to be considered a compensatory change. Furthermore, it is unlikely that pre-lymphatic fluid channels (2) evolved to greater efficiency in Chy mice, because such a modification would be expected to translate into improved lymphatic transport of macromolecules. Instead, we found that clearance of soluble lymphatic tracers was markedly reduced in Chy mice, arguing against compensatory improvements in processes associated with both molecular and cellular transport. Thus, based on the present findings, we propose that lymphatic capillaries in WT mouse skin evolved to the density they did in order to allow for optimal molecular transport and that the threshold of lymphatic density needed to support the migration of actively motile DCs, and perhaps other immune cells, is far lower. This conclusion, while unexpected, now seems logical given that macromolecular transport through lymphatic vessels occurs on a very different time scale (minutes) to cellular transport (hours). That the rate of DC migration is regulated by other features of lymphatic vessels such as adhesion of DCs within the lumen of lymphatic capillaries (12) is consistent with the concept that DC migration is rate-limited by different processes than molecular transport.

Chy LNs draining the skin exhibited a reduced cellularity in the face of lymphatic hypoplasia. That the popliteal LN, which drains only the rear footpad and not the body trunk where lymphatics are at least partly intact (39), is actually absent in Chy mice suggests that functional lymphatics are needed for a LN to form properly or be sustained. Although LN anlagen may be Prox-1- and therefore lymphatic vessel-independent (40), maintenance of LN integrity may require lymph flow. Indeed this possibility is consistent with reduced LN size when afferent lymphatics are surgically severed (41), which also results in altered HEV maturation and T-B cell compartmentalization. Further, DCs, including those from lymph, coordinate LN T cell homeostasis at least in part through enhancing HEV formation (42–44). However, critical elements derived from lymph likely include more than migratory DCs because skin-draining LNs still form in K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice that lack lymph-migrating DCs (20) (Fig. 1G).

Indeed, we observed that the typical lymphadenopathy associated with immunization failed in Chy mice. Although DCs have been linked to lymphadenopathy, our data suggest that intact DC migration may not be sufficient to coordinate lymphadenopathy in Chy mice. Earlier work from our laboratory revealed that lymphangiogenesis was associated with and required for lymphadenopathy (29). Thus, the failure of Chy mice to exhibit lymphadenopathy may be due to attenuated signalling of VEGFR3 by lymphatic endothelial cells. In the face of smaller baseline LNs in the Chy mouse, and their inability to exhibit lymphadenopathy in response to immunization, we find normal humoral immune responses at sites where DC migration remains proportional to overall LN cellularity, a result that is distinct from the impaired humoral responses observed in mice devoid of lymphatic capillaries in skin and devoid of lymph-trafficking DCs. This finding, in our view, highlights the greater importance of LN cellular composition, such as balanced ratios between lymph-homing and resident DCs and lymphocytes, than overall cellularity in driving an effective immune response.

Chy mice carry a dominant negative mutation in one allele. They serve as a useful tool to examine the VEGFR3 axis in lymphatic biology, as mutations in Milroy patients with primary lymphedema are found in the vegfr3 gene (15). The regionalized lymphatic defects in Chy mice are reminiscent of primary lymphedema patients, where body extremities, particularly lower extremities, are typically most affected (45, 46). The regional differences in lymphatic capillaries of the Chy mouse also adds a layer of complexity to the role of VEGFR3 in lymphatic development and highlights differences in anatomic regions even within the skin. Chy-3 mice, which are haploinsufficient for vegfc, also exhibit a regionalized form of lymphedema primarily affecting the lower limbs (47). VEGFR3 signalling is thought to be modulated through the co-receptor neuropilin-2 (NP-2) in the control of anatomic differences in lymphatic hypoplasia (15). NP-2, which binds VEGF-C and VEGF-D and is internalized with VEGFR3 upon ligand stimulation (48), is expressed by intestinal, but not cutaneous, lymphatic vessels (15). NP-1 was recently shown to regulate the recycling of VEGFR2 (49). Since haploinsufficient Chy mice are not completely devoid of VEGFR3 signalling, regional differences in receptor recycling and other pathways that affect signalling output could be crucial to the development of residual, functional lymphatic capillaries.

Through skin transplantation, we demonstrated that the introduction of a limited number of lymphatic capillaries restores DC mobilization, suggesting this approach may prove to have therapeutic value. Indeed some microsurgery techniques have shown success in lymphedema patients (50, 51) as well as in experimental models of skin transplantation to areas of secondary lymphedema (52). In addition to restoration of DC migration, we also observed lymphatic capillaries in and adjacent to the transplant in the WT - Chy group and, to a lesser extent, the Chy - Chy group. The lymphangiogenesis was higher in the WT - Chy group compared with the Chy - Chy or sham surgery groups, suggesting that, at least to some extent, donor LECs may proliferate and migrate to form new vessels. Indeed our GFP donor experiments lend credence to this possibility, and the presence of collecting vessels in the ear of Chy mice (Figure 4H) suggest donor capillaries may anastomose with endogenous collectors. Consistent with the heightened lymphangiogenesis in WT - Chy transplants, most lymphangiogenesis in adults occurs through sprouting from existing vessels (53). The more limited restoration, which occurred in the groups lacking pre-existing lymphatic vessels (Chy transplanted tissue or Chy sham-operated mice), may be due to local increases in VEGF-C as part of the surgery-associated inflammation. It is possible that the appearance of a low number of LYVE-1+ lymphatic capillaries observed after Chy–Chy transplant (Figure 7C) either results from sprouting of, or anastomosis with, the collecting vessels already present (Figure 4H), thereby facilitating DC migration in a small number of these recipients.

In summary, we show that the presence of very rare lymphatic capillaries in Chy mouse skin retards molecular transport through lymphatics but allows DCs to mobilize from the skin to LNs through the lymphatic vasculature normally and without delay. Further, these results reveal regional differences in lymphatic capillaries in the Chy mouse, with residual capillaries found on the body trunk while they are absent in the extremities. These data importantly add to our understanding of the requirements for DC transit through the lymphatic vasculature, aid in defining how the immune system is affected by lymphatic hypoplasia, and may have a translational aspect and lend further credence to surgical treatment of patients with peripheral lymphedema.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Kari Alitalo for providing K14-VEGFR3-Ig mice, Hwee Ying Lim and Veronique Angeli for technical advice and David Zawieja for helpful discussion. The authors would like to thank the Microvascular Surgery Core at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine for their expert assistance. We would also like to thank Drs. M. Ingersoll and E. Gautier for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. Current address of A. M. Platt is University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom; J.M.R is at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, and E.L.K is at the Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, Washington.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant HL096539 to G.J.R. and M.A.S (dual P.I.), and grants NIH AI046953 and AHA (0740052) to G. J. R. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed at the MSSM-Microscopy Shared Resource Facility, supported by NIH-NCI grant 5R24 CA095823-04, NSF grant DBI-9724504 and NIH grant 1 S10 RR0 9145-01.

References

- 1.Randolph GJ, Angeli V, Swartz MA. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nri1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muthuchamy M, Zawieja D. Molecular regulation of lymphatic contractility. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:89–99. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockson SG. Causes and consequences of lymphatic disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207(Suppl 1):E2–E6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JB, McIntosh GH, Morris B. The traffic of cells through tissues: a study of peripheral lymph in sheep. J Anat. 1970;107:87–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberberg-Sinakin I, Thorbecke GJ, Baer RL, Rosenthal SA, Berezowsky V. Antigen-bearing langerhans cells in skin, dermal lymphatics and in lymph nodes. Cell Immunol. 1976;25:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(76)90105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen CP, Steinman RM, Witmer-Pack M, Hankins DF, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Migration and maturation of Langerhans cells in skin transplants and explants. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1483–1493. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukas M, Stossel H, Hefel L, Imamura S, Fritsch P, Sepp NT, Schuler G, Romani N. Human cutaneous dendritic cells migrate through dermal lymphatic vessels in a skin organ culture model. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1293–1299. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12349010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoitzner P, Holzmann S, McLellan AD, Ivarsson L, Stossel H, Kapp M, Kammerer U, Douillard P, Kampgen E, Koch F, et al. Visualization and characterization of migratory Langerhans cells in murine skin and lymph nodes by antibodies against Langerin/CD207. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:266–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baluk P, Fuxe J, Hashizume H, Romano T, Lashnits E, Butz S, Vestweber D, Corada M, Molendini C, Dejana E, et al. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2349–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pflicke H, Sixt M. Preformed portals facilitate dendritic cell entry into afferent lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2925–2935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tal O, Lim HY, Gurevich I, Milo I, Shipony Z, Ng LG, Angeli V, Shakhar G. DC mobilization from the skin requires docking to immobilized CCL21 on lymphatic endothelium and intralymphatic crawling. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2141–2153. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miteva DO, Rutkowski JM, Dixon JB, Kilarski W, Shields JD, Swartz MA. Transmural flow modulates cell and fluid transport functions of lymphatic endothelium. Circ Res. 2010;106:920–931. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brice G, Child AH, Evans A, Bell R, Mansour S, Burnand K, Sarfarazi M, Jeffery S, Mortimer P. Milroy disease and the VEGFR-3 mutation phenotype. J Med Genet. 2005;42:98–102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karkkainen MJ, Saaristo A, Jussila L, Karila KA, Lawrence EC, Pajusola K, Bueler H, Eichmann A, Kauppinen R, Kettunen MI, et al. A model for gene therapy of human hereditary lymphedema. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12677–12682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221449198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makinen T, Jussila L, Veikkola T, Karpanen T, Kettunen MI, Pulkkanen KJ, Kauppinen R, Jackson DG, Kubo H, Nishikawa S, et al. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis with resulting lymphedema in transgenic mice expressing soluble VEGF receptor-3. Nat Med. 2001;7:199–205. doi: 10.1038/84651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbiani DF, Finch RA, Jager D, Muller WA, Sartorelli AC, Randolph GJ. The leukotriene C(4) transporter MRP1 regulates CCL19 (MIP-3beta, ELC)-dependent mobilization of dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Cell. 2000;103:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 1999;11:753–761. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas SN, Rutkowski JM, Pasquier M, Kuan EL, Alitalo K, Randolph GJ, Swartz MA. Impaired Humoral Immunity and Tolerance in K14-VEGFR-3-Ig Mice That Lack Dermal Lymphatic Drainage. J Immunol. 2012;189:2181–2190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, Chu FF, Randolph GJ, Rudensky AY, Nussenzweig M. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1170540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakubzick C, Bogunovic M, Bonito AJ, Kuan EL, Merad M, Randolph GJ. Lymph-migrating, tissue-derived dendritic cells are minor constituents within steady-state lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2839–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poulin LF, Henri S, de Bovis B, Devilard E, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B. The dermis contains langerin+ dendritic cells that develop and function independently of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3119–3131. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginhoux F, Collin MP, Bogunovic M, Abel M, Leboeuf M, Helft J, Ochando J, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Grisotto M, et al. Blood-derived dermal langerin+ dendritic cells survey the skin in the steady state. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3133–3146. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bursch LS, Wang L, Igyarto B, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Kaplan DH, Hogquist KA. Identification of a novel population of Langerin+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3147–3156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flacher V, Douillard P, Ait-Yahia S, Stoitzner P, Clair-Moninot V, Romani N, Saeland S. Expression of langerin/CD207 reveals dendritic cell heterogeneity between inbred mouse strains. Immunology. 2008;123:339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Shortman K, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angeli V, Ginhoux F, Llodra J, Quemeneur L, Frenette PS, Skobe M, Jessberger R, Merad M, Randolph GJ. B cell-driven lymphangiogenesis in inflamed lymph nodes enhances dendritic cell mobilization. Immunity. 2006;24:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu C, Edwards EW, Tacke F, Angeli V, Llodra J, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Garin A, Haque NS, Peters W, van Rooijen N, et al. Role of CCR8 and other chemokine pathways in the migration of monocyte-derived dendritic cells to lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1231–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun A, Worbs T, Moschovakis GL, Halle S, Hoffmann K, Bolter J, Munk A, Forster R. Afferent lymph-derived T cells and DCs use different chemokine receptor CCR7-dependent routes for entry into the lymph node and intranodal migration. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:879–887. doi: 10.1038/ni.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makinen T, Adams RH, Bailey J, Lu Q, Ziemiecki A, Alitalo K, Klein R, Wilkinson GA. PDZ interaction site in ephrinB2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2005;19:397–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.330105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alitalo K, Tammela T, Petrova TV. Lymphangiogenesis in development and human disease. Nature. 2005;438:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nature04480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, Lyubynska N, Achen MG, Hicklin DJ, Jeltsch M, Petrova TV, Pytowski B, Stacker SA, et al. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:247–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vigl B, Aebischer D, Nitschke M, Iolyeva M, Rothlin T, Antsiferova O, Halin C. Tissue inflammation modulates gene expression of lymphatic endothelial cells and dendritic cell migration in a stimulus-dependent manner. Blood. 2011;118:205–215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang CW, Strong BS, Miller MJ, Unanue ER. Neutrophils influence the level of antigen presentation during the immune response to protein antigens in adjuvants. J Immunol. 2010;185:2927–2934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerovic V, Houston SA, Scott CL, Aumeunier A, Yrlid U, Mowat AM, Milling SW. Intestinal CD103(-) dendritic cells migrate in lymph and prime effector T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tilney NL. Patterns of lymphatic drainage in the adult laboratory rat. J Anat. 1971;109:369–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vondenhoff MF, van de Pavert SA, Dillard ME, Greuter M, Goverse G, Oliver G, Mebius RE. Lymph sacs are not required for the initiation of lymph node formation. Development. 2009;136:29–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.028456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mebius RE, Streeter PR, Breve J, Duijvestijn AM, Kraal G. The influence of afferent lymphatic vessel interruption on vascular addressin expression. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wendland M, Willenzon S, Kocks J, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hammerschmidt SI, Schumann K, Kremmer E, Sixt M, Hoffmeyer A, Pabst O, et al. Lymph node T cell homeostasis relies on steady state homing of dendritic cells. Immunity. 2011;35:945–957. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moussion C, Girard JP. Dendritic cells control lymphocyte entry to lymph nodes through high endothelial venules. Nature. 2011;479:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumamoto Y, Mattei LM, Sellers S, Payne GW, Iwasaki A. CD4+ T cells support cytotoxic T lymphocyte priming by controlling lymph node input. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8749–8754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100567108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bollinger A, Isenring G, Franzeck UK, Brunner U. Aplasia of superficial lymphatic capillaries in hereditary and connatal lymphedema (Milroy's disease) Lymphology. 1983;16:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellor RH, Hubert CE, Stanton AW, Tate N, Akhras V, Smith A, Burnand KG, Jeffery S, Makinen T, Levick JR, et al. Lymphatic dysfunction, not aplasia, underlies Milroy disease. Microcirculation. 2010;17:281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dellinger MT, Hunter RJ, Bernas MJ, Witte MH, Erickson RP. Chy-3 mice are Vegfc haploinsufficient and exhibit defective dermal superficial to deep lymphatic transition and dermal lymphatic hypoplasia. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2346–2355. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karpanen T, Heckman CA, Keskitalo S, Jeltsch M, Ollila H, Neufeld G, Tamagnone L, Alitalo K. Functional interaction of VEGF-C and VEGF-D with neuropilin receptors. FASEB J. 2006;20:1462–1472. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5646com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ballmer-Hofer K, Andersson AE, Ratcliffe LE, Berger P. Neuropilin-1 promotes VEGFR-2 trafficking through Rab11 vesicles thereby specifying signal output. Blood. 2011;118:816–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee BB, Kim YW, Kim DI, Hwang JH, Laredo J, Neville R. Supplemental surgical treatment to end stage (stage IV-V) of chronic lymphedema. Int Angiol. 2008;27:389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campisi C, Bellini C, Accogli S, Bonioli E, Boccardo F. Microsurgery for lymphedema: clinical research and long-term results. Microsurgery. 2010;30:256–260. doi: 10.1002/micr.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slavin SA, Van den Abbeele AD, Losken A, Swartz MA, Jain RK. Return of lymphatic function after flap transfer for acute lymphedema. Ann Surg. 1999;229:421–427. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199903000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Y, Rajantie I, Ilmonen M, Makinen T, Karkkainen MJ, Haiko P, Salven P, Alitalo K. Preexisting lymphatic endothelium but not endothelial progenitor cells are essential for tumor lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3737–3740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.