Abstract

Purpose

Micro-vibration culture system was examined to determine the effects on mouse and human embryo development and possible improvement of clinical outcomes in poor responders.

Materials and methods

The embryonic development rates and cell numbers of blastocysts were compared between a static culture group (n = 178) and a micro-vibration culture group (n = 181) in mice. The embryonic development rates and clinical results were compared between a static culture group (n = 159 cycles) and a micro-vibration culture group (n = 166 cycles) in poor responders. A micro-vibrator was set at a frequency of 42 Hz, 5 s/60 min duration for mouse and human embryo development.

Results

The embryonic development rate was significantly improved in the micro-vibration culture group in mice (p < 0.05). The cell numbers of mouse blastocysts were significantly higher in the micro-vibration group than in the static culture group (p < 0.05). In the poor responders, the rate of high grade embryos was not significantly improved in the micro-vibration culture group on day 3. However, the optimal embryonic development rate on day 5 was improved in the micro-vibration group, and the total pregnancy rate and implantation rate were significantly higher in the micro-vibration group than in the static culture group (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Micro-vibration culture methods have a beneficial effect on embryonic development in mouse embryos. In poor responders, the embryo development rate was improved to a limited extent under the micro-vibration culture conditions, but the clinical results were significantly improved.

Keywords: Embryo culture, Micro-vibration, Static culture, Dynamic culture

Introduction

A major consideration in assisted reproductive technology (ART) is providing an environment that is similar to the internal body conditions during germ cell development in vitro. Technologies have been improved for maintaining the temperature and the appropriate in vivo-like pH range [1]. Moreover, for several decades, researchers have been developing technologies to make culture media and additives that can facilitate germ cell development [2–6].

Nevertheless, despite efforts to improve the quality of ART, one of the unresolved issues regarding current embryonic culture conditions is the static culture system. Fertility clinics worldwide culture embryos in the static state. Before implantation, the oocytes and zygotes within the oviduct and uterus are constantly moving and being stimulated by the surrounding environment during natural pregnancy [7–9]. Moving and stimulating sources that influence embryonic development include shear stress by tubal fluid flow, compression by peristaltic tubal wall movement, buoyancy and kinetic friction forces between the embryo and cilia [10, 11]. The combination of these in vivo mechanical forces leads to an average ovum velocity of 0.1 μm/s and a maximum velocity of up to 8.6 μm/s [12–15]. These in vivo mechanical forces are believed to induce cell-to-cell communication, exert beneficial effects by refreshing the fluid surrounding the embryo and eliminate metabolites emitted from embryos [16–19]. Studies to achieve higher quality embryos by external stimuli using machines (i.e., tilting machines and micro-vibrators) to replicate in vivo mechanical forces have been recently reported [20, 21]. Embryonic culture using a micro-vibrator as an external stimulus has been actively investigated [22]. The present study investigated the effects of a micro-vibrator on embryo development.

Poor responders who require large doses of stimulant medications and who produce less than an optimal number of oocytes remain a significant challenge in ART [23]. Poor responders exhibit advanced age, previous ovarian surgery or pelvic adhesions [24, 25], all of which can contribute to a reduced oocyte and embryo quality in comparison with normal responders. To improve the pregnancy rate in poor responders, various approaches have been attempted, but a satisfactory solution has not been reached [26, 27]. However, most of the approaches have focused on specific aspects by refining induction protocols in poor responders to increase the number of collected oocytes and the quality of the embryos [28, 29]. The purpose of the present study was to improve embryo quality in poor responders using a unique culture method.

The aim of this investigation was to evaluate the effect of micro-vibration on mouse and human embryonic development and the effect of micro-vibration on the clinical results in poor responders.

Methods

Mouse embryonic culture and Hoechst staining

All animal care and use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Kangwon National University.

The protocol for handling the mouse embryos followed previous laboratory methods [30]. Briefly, 6-week-old B6D2 F1 mice were superovulated with pregnant mare serum gonadotrophin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Twenty hours after hCG injection, the female mice were sacrificed, and single-cell zygotes were collected and cultured into mouse tubal fluid (MTF) +4 mg/mL human serum albumin medium at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5 % CO2. Each 50 μL MTF droplet contained 5 mouse embryos and was cultured as a static culture group (n = 178) and a micro-vibration culture group (n = 181).

Observation of mouse embryonic development was performed on days 3 (at 70 h post hCG) and 5 (at 120 h post hCG). On day 3, the embryos were evaluated for their quality and cell stages. On day 5, the blastocyst was graded as a hatching blastocyst, expanded blastocyst, intermediate expanded blastocyst, early blastocyst or pre-morula stage.

After observation on day 5, the blastocysts were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich, B2261) to determine the effect of micro-vibration stimuli on mouse embryonic development. Mouse blastocysts were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), stained for 15 min with 0.5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 and subsequently washed 3 times in PBS (0.1 % polyvinyl alcohol). The blastocysts were fixed by Permount solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) and examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51-FL, Japan) [31, 32].

Ovulation induction and embryonic culture in poor responders

This study was approved by the Maria Fertility Hospital Institutional Review Board. Certain protocols for various poor responders are routinely utilized to maximize the numbers of eggs in this hospital. Some patients were administered a GnRH agonist on the second or third day of the menstrual cycle, but its administration lasted for 3 days, and a GnRH antagonist was then administered to prevent premature ovulation. Some patients were administered only a low dose of the GnRH agonist. Some patients were administered the GnRH agonist during the luteal phase, but the agonist administration was discontinued when the menstrual cycle started. The other patients followed a modified natural cycle. The poor responders were randomly distributed into a static culture group or a micro-vibration culture group during the same period (July to December 2012).

Fertilization was assessed 15–18 h after insemination based on the presence of 2 pronuclei. The zygotes were washed and cultured in groups of less than 5 in a 50 μL micro-droplet (Sydney IVF Cleavage Medium-CM; COOK, Brisbane, Australia) for 48 h, and the embryos were subsequently selected for transfer. Some surplus embryos were culture in a 50 μL micro-droplet (Sydney IVF Blastocyst Medium-BM; COOK, Brisbane, Australia) for blastocyst development, and the others were cryopreserved or discarded. All culturing of the embryos was performed in a CO2:O2:N2 (6 %:5 %:89 %) environment.

Micro-vibration

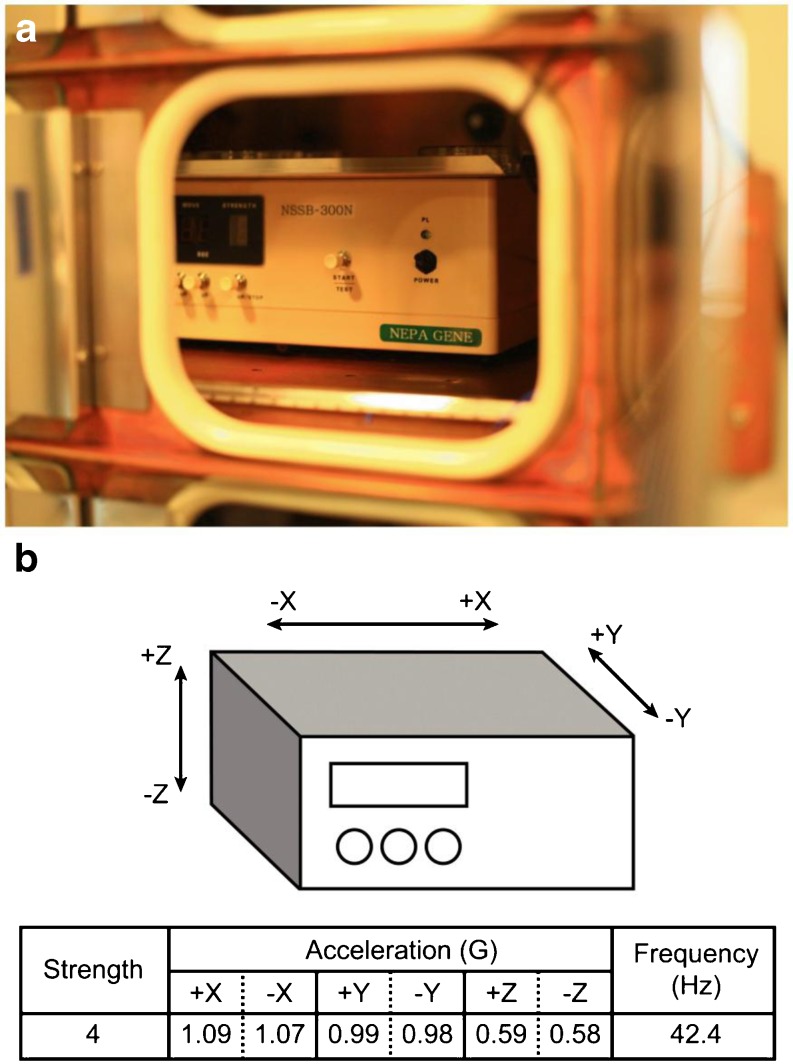

In the present study, a micro-vibrator (NSSB-300, Nepa Gene, Ichikawa, Chiba, Japan) was set at a frequency of 42 Hz, 5 s/60 min duration for mouse and human embryo development based on the previous reports [21, 22, 33]. Micro-vibration was applied to the single-cell zygote stage in the mouse. Moreover, in the poor responders, micro-vibration was applied to the pronuclear zygote stage. The micro-vibrator installed in an incubator and its unique 3-dimensional movements are illustrated Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a Appearance of the micro-vibrator installed in the incubator. b 3-dimensional movement of the micro-vibrator (according to the product specifications provided by Nepa Gene)

Embryo transfer and clinical results in the poor responders

The static culture group underwent 159 cycles, and the micro-vibration group underwent 166 cycles. Embryo selection for transfer was performed on day 3. The number of embryos for transfer was limited to 2. Some poor responders received 3 embryos, depending on their clinical history (i.e., repeat failures or old age). Generally, the cell division rate in poor responders is slower than in good responders because of the poor-quality oocytes and sub-optimal number of collected oocytes in the former [24]. Therefore, based on the report by Ziebe et al. [34]., the embryos were divided into 3 grades. Grade A was the 6–8 cell stage (10 % > fragmentation), grade B was the 4–5 cell stage (10 % ≤ fragmentation <30 %), and grade C was the less than 4 cell stage (30 % ≤ fragmentation). Some of the surplus embryos after transfer were cultured for blastocyst development under the same conditions. Others were cryopreserved at the cleavage stage, and the remaining embryos were discarded. The blastocysts were evaluated on day 5 and 6 according to Gardner’s grading methods and were cryopreserved or discarded based on their quality [35]. Pregnancy was assessed by serum hCG 14 days after the administration of progesterone, and implantation was confirmed by the presence of a gestational sac.

The clinical data and results were summarized into 2 types to compare the effect of micro-vibration stimulus on human embryonic culture. The first type included whole sets of clinical data and the results from poor responders for entire study periods. The second type included partial data and the results from the more severe poor responders, from whom fewer than 6 oocytes were collected. It was difficult to compare the effect of micro-vibration on human blastocyst development in the more severe poor responders because there were an insufficient number of surplus embryos for blastocyst development after transfer. The data included mildly poor responders, from whom more than 6 oocytes were collected; these results were useful to compare the effect of micro-vibration on blastocyst development but did not exhibit a marked influence on the clinical results.

Statistical analysis

The mouse and human embryonic quality and development rates were analyzed with the χ2 test and t test. Clinical data in the poor responders were compared using the χ2 test.

Results

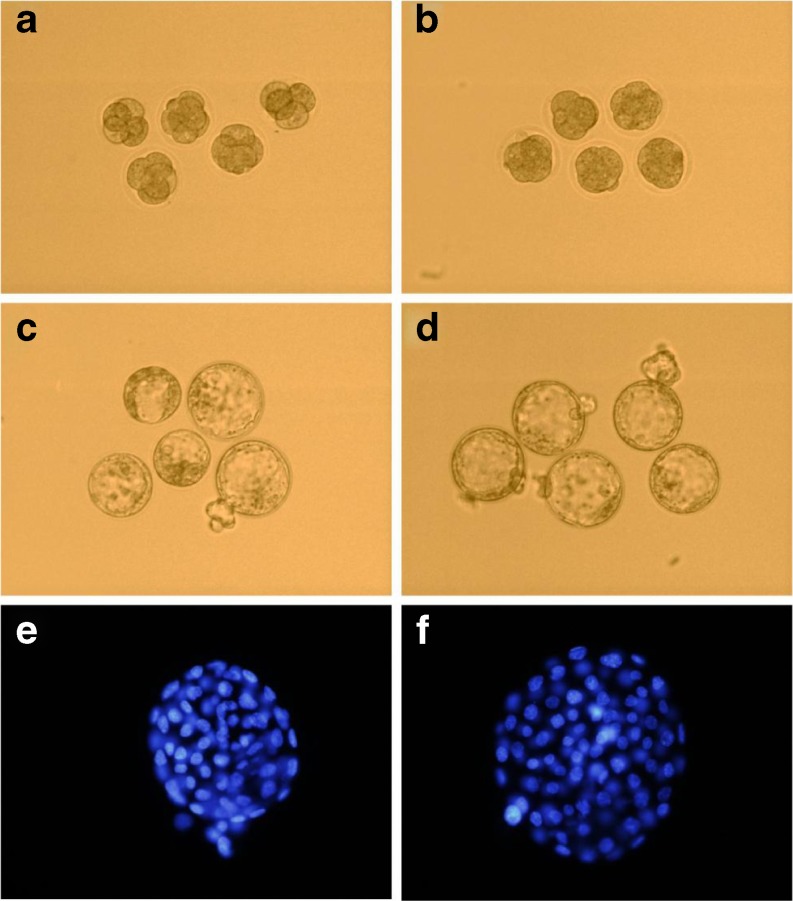

Illustrations of the mouse embryonic development between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group on days 3 (A, B) and 5 (C, D) are shown in Fig. 2. A comparison of the cell numbers of mouse blastocysts (E, F) between the static culture group and the micro-vibration group is also shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mouse embryo quality between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group on day 3 (a, b) and day 5 (c, d) and a comparison of the cell numbers between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group (e, f) a Static cultured embryos on day 3, magnification ×200 b Micro-vibration cultured embryos on day 3, magnification ×200 c Static cultured embryos on day 5, magnification ×200 d Micro-vibration cultured embryos on day 5, magnification ×200 e Stained blastocyst from the static culture, magnification ×400 f Stained blastocyst from the micro-vibration culture, magnification ×400

In both culture groups, differences in the optimal development rate on days 3 and 5 were demonstrated. On day 3, 48 (26.5 %) embryos in the 7–8 cell stage were present in the micro-vibration culture group, whereas only 21 (11.8 %) were present in the static culture group. On day 5, 67 (37.0 %) embryos had reached or passed the hatching blastocyst stage in the micro-vibration culture group, whereas only 32 (18.0 %) had reached or passed this stage in the static culture group (Table 1). The number of embryos that developed at the optimal rate in the micro-vibration group was significantly higher than in the static culture group.

Table 1.

Comparison of the optimal development rate on day 3 and day 5 between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group in the mouse embryonic culture

| Cell stages | Day 3 | Day 5 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-7 cell | 6-5 cell | 4 cell | < 3 cell | > HB | EdB | MeB | ErB | < Mor. | |

| Static culture Group (%) (n=178) | 21 (11.8) | 27 (15.2) | 114 (64.0) | 16 (9.0) | 32 (18.0) | 70 (39.3) | 32 (18.0) | 10 (5.6) | 34 (19.1) |

| Micro-vibration culture group (%) (n=181) | 48* (26.5) | 43 (23.8) | 73 (40.3) | 17 (9.4) | 67* (37.0) | 65 (35.9) | 17 (9.4) | 13 (7.2) | 19 (10.5) |

HB hatching blastocysts (including hatched blastocysts); EdB expanded blastocysts; MeB intermediate expanded blastocysts; ErB early blastocysts; *p < 0.05

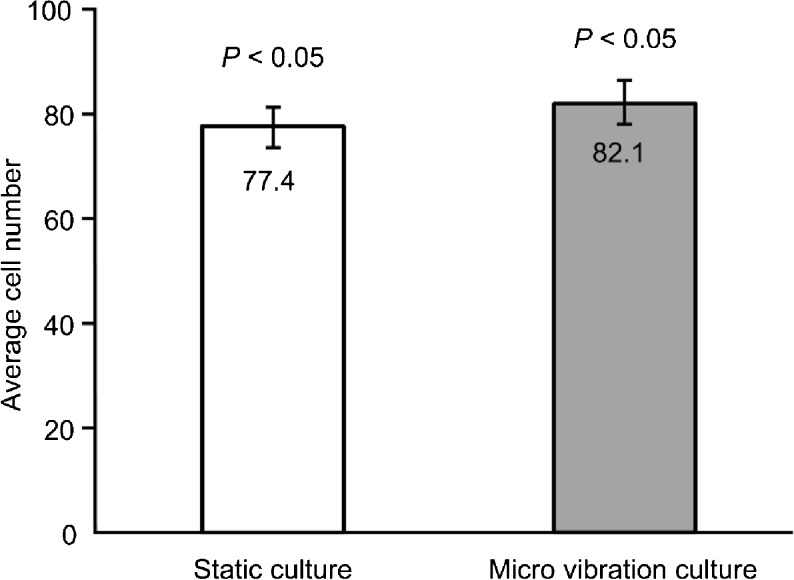

A comparison of the cell numbers of stained blastocysts between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group is shown in Fig. 3. The cell numbers of mouse blastocysts in the micro-vibration culture group were significantly higher than in static culture group.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the average cell numbers of mouse blastocysts between the static culture group and the micro-vibration culture group. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

In the poor responders, there were no significant differences in the age, number of oocytes, fertilization rate, zygote number and embryo transfer number between the 2 groups. The rate of high grade embryos was not improved significantly in the micro-vibration culture group on day 3. However, the total pregnancy and implantation rates were significantly higher in the micro-vibration culture group. Moreover, the blastocyst development rate in the micro-vibration culture group on day 5 was higher than in the static culture group. The total blastocyst development rate on day 5 and 6 was not significantly different between the 2 groups (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of the poor responders

| Static culture (n = 159) | Micro-vibration culture (n = 166) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 38.5 ± 4.1 | 37.9 ± 4.4 | n.s. |

| Mean number of oocytes | 5.2 ± 3.9 | 5.4 ± 3.5 | n.s. |

| Fertilization rate | 76.1 % (579/761) | 80.0 % (670/837) | n.s. |

| Mean number of zygote | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 4.0 ± 2.6 | n.s. |

| The rate of high grade embryos on day 3 (grade A) | 60.4 % (317/525) | 66.4 % (397/598) | n.s. |

| Mean number of transferred embryos | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | n.s. |

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes and blastocyst development rates in the surplus embryos

| Static culture | Micro-vibration culture | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of embryo transfer cycles | 159 | 166 |

| Total pregnancy rate | 13.2 % (21) | 22.9 % (38)* |

| Implantation rate | 6.7 % (23) | 11.6 % (44)* |

| No. of surplus embryos | 195 | 261 |

| Blastocysts development rate on day 5 | 7.4 % (14) | 16.9 % (44)* |

| Total blastocysts development rate on day 5 and 6 | 25.6 % (50) | 32.2 % (84) |

*p < 0.05

In the more severe poor responders, in whom fewer than 6 oocytes were collected, the total pregnancy rate was significantly higher in the micro-vibration culture group than in the static culture group (Table 4). The implantation rate was increased in the micro-vibration culture group but not significantly.

Table 4.

Clinical results of a limited population (no. of oocytes ≤5) in poor responders

| Static culture | Micro-vibration culture | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of embryo transfer cycles | 96 | 95 |

| Age (year) | 39.3 ± 4.1 | 38.7 ± 4.2 |

| Mean number of oocytes | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.3 |

| Fertilization rate | 84.8 % (207/244) | 84.9 % (219/258) |

| Mean number of transferred embryos | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.8 |

| Total pregnancy rate | 10.4 % (10) | 21.1 % (20)* |

| Implantation rate | 6.2 % (11/178) | 11.3 % (22/194) |

*p < 0.05

Discussion

In this study, micro-vibration stimulus during mouse embryonic culture had a positive effect on the development rates. During mouse embryonic development, the number of mouse embryos in a 50 μL MTF droplet was limited to 5 to minimize the influence of group culture [36, 37] and to maximize the effect of the experimental conditions between the static culture and the micro-vibration culture [20]. The mouse embryonic development rate when the O2 pressure is low (5 %) is commonly faster than when the O2 pressure is high (20 %) [38, 39]. These conditions, including limiting the number of mouse embryos in a droplet and high O2 pressure, did not have a positive effect on the mouse embryonic development. Even under these adverse conditions, the mouse embryonic development rate was increased significantly in response to the micro-vibration stimulus.

Although the beneficial effects of micro-vibration have been reported already in human in vitro fertilization, basic information of micro-vibration culture condition on various mammalian embryo cultures is not enough. First study of micro-vibration on porcine immature oocytes encouraged researchers to apply to mammalian embryos. In this study, it was approved that the mouse embryo development was significantly improved under the micro-vibration conditions. Studies of various mammalian embryos culture include this study on micro-vibration culture condition would be useful information for dynamic culture or embryo activation.

Based on a study conducted on immature porcine oocytes and embryos, the blastocyst formation rate is significantly increased at a frequency of 20 Hz, 5 s/30 to 60 min duration [21]. Isachenko’s group has reported several relevant results. In their 2010 study, the micro-vibration frequency and interval were 20 Hz and 5 s/60 min, respectively, and the clinical results were significantly improved [22]. Furthermore, in their 2011 study, the micro-vibration frequency and interval were 44 Hz and 5 s/60 min, respectively, and the clinical results were significantly improved [33]. In the present study, the mouse embryo development rate and clinical results of the poor responders were significantly improved at a frequency of 42 Hz, 60 min duration. These reports indicate that the frequency range that has a positive effect on mammalian embryo development is broad, namely, from 20 Hz to 44 Hz.

The parameters of movement were not directly transmitted to the embryos in the media droplet. Isachenko’s group reported that the acceleration of cells is slower than these rates when the plate is vibrating [33]. There may be a frictional force between the dish and the plate, between the dish and the mineral oil, between the mineral oil and the media droplet and between the media and the embryos. The viscosity of the media should also be considered a frictional force. Reduced acceleration and frequency may cause frequencies of cilia beating that range from 5 to 20 Hz [40]. Cilia beating, pulsatile muscle contractions of the uterus and oviduct and sperm motility generate forces that move fluids [41]. The fluid motion increases the positive effect of the hormones and nutrients on the embryos [42, 43]. It is difficult to define the combined in vivo mechanical forces that produce various movement patterns in the oviduct fluid. Moreover, it is difficult to quantify each in vivo mechanical force. However, it is clear that in vivo mechanical forces exert a beneficial effect on natural pregnancy. Furthermore, a micro-vibration embryonic culture method that mimics in vivo mechanical forces would be a valuable approach to improving the quality of in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. Other dynamic culture systems have been recently reported, including a microfluidic dynamic embryonic culture system [44, 45] and a tilting embryonic culture system [20]. Each system has pros and cons and presents challenges for practical use [46]. With improvements in each unique culture system, a dynamic culture system will be ultimately established.

In normal responders, the human embryonic development and clinical results were significantly improved under the micro-vibration condition [22]. Because the better quality of oocytes and embryos in normal responders, the positive effect on embryonic development could be observed more easily. In poor responders, large doses of stimulant medication, sub-optimal numbers of oocytes, poor-quality embryos, old age and a defective endometrium are the various factors that influence a poor prognosis [23–25]. The human embryo development rate were improved to a limited extent, suggesting that it is difficult to improve the cell division rate in poor responders because of their poor-quality oocytes and sub-optimal numbers of collected oocytes. However, the total pregnancy and implantation rates were significantly increased when a micro-vibration stimulus was applied to the human embryonic culture. This finding indicates that a slight improvement of embryo quality in poor responders can significantly influence the clinical results. In conclusion, this study suggests that micro-vibration embryo culture condition would be another approach for poor responders that remain a significant challenge in IVF.

The micro-vibration embryonic culture method would be valuable for in vitro maturation (IVM) or repeated IVF failures. Micro-vibration did not influence the maturation of porcine immature oocytes. However, the blastocyst development rates were significantly improved by micro-vibration [21]. It is not known whether micro-vibration has a positive effect on the maturation of human immature oocytes or on the clinical results in IVM. Moreover, it is still unclear whether micro-vibration has a beneficial effect on embryo development and implantation after repeated IVF failures. Further investigations are necessary to determine the effects of micro-vibration on other poor prognoses in IVF.

Footnotes

Capsule Micro-vibration culture system can improve mouse embryo development rate and clinical outcomes in poor responders.

Contributor Information

Yong Soo Hur, Phone: +82-2-22505572, FAX: +82-2-22505585, Email: geaher@mariababy.com.

Jeong Hyun Park, Email: jhpark@kangwon.ac.kr.

Eun Kyung Ryu, Email: ekryu@mariababy.com.

Sung Jin Park, Email: sjpark@mariababy.com.

Jun Ho Lee, Email: cleansunday@mariababy.com.

Soo Hee Lee, Email: dntb33@mariababy.com.

Jung Yoon, Email: jeong7@mariababy.com.

San Hyun Yoon, Email: shyoon@mariababy.com.

Chang Young Hur, Email: cyhur@mariababy.com.

Won Don Lee, Email: don@mariababy.com.

Jin Ho Lim, Email: lim@mariababy.com.

References

- 1.Gardner DK, Weissman A, Howles CM, Shoham Z. Textbook of assisted reproductive techiniques. In: Gardner DK, Lane M, editors. Culture systems for the human embryo. 2. London and New York: Taylor & Francis; 2004. pp. 211–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Yosef D, Amit A, Azem F, Schwartz T, Cohen T, Mei-Raz N, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of two embryo culture systems: P1 medium by Irvine Scientific and the Cook IVF Medium. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2004;21:291–5. doi: 10.1023/B:JARG.0000043702.35570.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balaban B, Urman B. Comparison of two sequential media for culturing cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts: embryo characteristics and clinical outcome. Reprod BioMedOnline. 2005;10:485–91. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki VW, Wilcox AL, Peterson CM, Parker-Jones K, Hatasaka HH, Gibson M, et al. Comparison of four media types during 3-day human IVF embryo culture. Reprod BioMedOnline. 2005;10:600–6. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane M, Gardner DK. Embryo culture medium; which is the best? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;21:83–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruber I, Klein M. Embryo culture media for human IVF: which possibilities exist? J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2011;12:110–7. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2011.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbert SA, Tam PY, Blandau RJ. Egg transport in the rabbit oviduct: the role of cilia and muscle. Science. 1976;191:1052–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1251215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauci LJ, Dillon R. Biofluidmechanics of reproduction. Ann Rev Fluid Mech. 2006;38:371–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.37.061903.175725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons RA, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O. The reproductive significance of human fallopian tube cilia. Hum Reprod. 2006;12:363–72. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Y, Wang F, Zhong W, Puscheck E, Hayley S, Rappolee DA. Shear stress induces preimplantation embryo death that is delayed by the zona pellucid and associated with stress-activated protein kinase-mediated apoptosis. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:45–55. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.049791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zervomanolakis I, Ott HW, Hadziomerovic D, Mattle V, Seeber BE, Virgolini I, et al. Physiology of upward transport in the human female genital tract. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1101:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1389.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwald GS. A study of transport of ova through rabbit oviduct. Fertil Steril. 1961;12:80–95. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)34028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portnow J, Talo A, Hodgson BJ. A random walk model of ovum transport. Bull Math Biol. 1977;39:349–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02462914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anand S, Guha SK. Mechanics of transport of the ovum in the oviduct. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1978;16:256–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02442424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbert SA, Becker DR, Szal SE. Ovum transport in the rat oviductal ampulla in the absence of muscle contractility. Biol Reprod. 1989;40:1131–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod40.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner DK, Lane M. Amino-acids and ammonium regulate mouse embryo development in culture. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:377–85. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmvall K, Camper L, Kimura JH, Lundgren-Akerlund E. Chondrocyte and chondrosarcoma cell integrins with affinity for collagen type II and their response to mechanical stress. Exp Cell Res. 1995;221:496–503. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukui Y, Lee ES, Araki N. Effect of medium renewal during culture in two different culture systems on development to blastocysts from in vitro produced early bovine embryos. J Anim Sci. 1996;74:2752–8. doi: 10.2527/1996.74112752x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JH, Thampatty BP. An introductory review of cell mechanobiology. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2006;6:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10237-005-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuura K, Hayashi N, Kuroda Y, Takiue C, Hirata R, Takenami M, et al. Improved development of mouse and human embryos using a tilting embryo culture system. Reprod BioMedOnline. 2010;20:358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizobe Y, Yoshida M, Miyoshi K. Enhancement of cytoplasmic maturation of in vitro-matured pig oocytes by mechanical vibration. J Reprod Dev. 2010;56:285–90. doi: 10.1262/jrd.09-142A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isachenko E, Maettner R, Isachenko V, Roth S, Kreienberg R, Sterzik K. Mechanical agitation during the in vitro culture of human pre-implantation embryos drastically increases the pregnancy rate. Clin Lab. 2010;56:569–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferraretti AP, Marca AL, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L, et al. ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor responder’ to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;0:1–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins JM, Davies DW, Devonport H, Anthony FW, Gadd SC, Watson RH, et al. Comparison of ‘poor’ responders with ‘good’ responders using a standard buserelin/human menopausal gonadotropin regime for in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:918–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keay SD, Liversedge NH, Mathur RS, Jenkins JM. Assisted conception following poor ovarian response to gonadotrophin stimulation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:521–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Land JA, Yarmolinskaya MI, Dumoulin JC, Evers JL. High-dose human menopausal gonadotrophin stimulation in poor responders does not improve in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:961–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surrey ES, Schoolcraft WB. Evaluating strategies for improving ovarian response of the poor responder undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:667–76. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frattarelli JL, Hill MJ, McWilliams GD, Miller KA, Bergh PA, Scott RT. A luteal estradiol protocol for expected poor-responders improves embryo number and quality. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1118–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoolcraft W, Schlenker T, Gee M, Stevens J, Wagley L. Improved controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in poor responder in vitro fertilization patients with a microdose follicle-stimulating hormone flare, growth hormone protocol. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:93–7. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu EK, Hur YS, Ann JY, Maeng JY, Park M, Park JH, et al. Vitrification of mouse embryos using the thin plastic strip method. Cli Exp Reprod Med. 2012;39:153–60. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2012.39.4.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arndt-Jovin DJ, Jovin TM. Analysis and sorting of living cells according to deoxyribonucleic acid content. J Histochem Cytochem. 1977;25:585–9. doi: 10.1177/25.7.70450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blau HM, Chiu CP, Webster C. Cytoplasmic activation of human nuclear genes in stable heterocaryons. Cell. 1983;32:1171–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isachenko V, Maettner R, Sterzik K, Strehler E, Kreinberg R, Hancke K, et al. In-vitro culture of human embryos with mechanical micro-vibration increases implantation rates. Reprod BioMedOnline. 2011;22:536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziebe S, Petersen K, Lindenberg S, Andersen AG, Gabrielsen A, Andersen AN. Embryo morphology or cleavage stage: how to select the best embryos for transfer after in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1545–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.7.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner DK, Lane M, Stevens J, Schlenker T, Schoolcraft WB. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1155–8. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melin J, Lee A, Foygel K, Leong DE, Quake SR, Yao MW. In vitro embryo culture in defined, Sub-microliter Volumes. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:950–5. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai SJ, Xu CL, Wang J, Sun YP, Chian RC. Effect of culture medium volume and embryo density on early mouse embryonic development: Tracking the development of the individual embryo. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:617–23. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9744-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn P, Harlow GM. The effect of oxygen on the development of preimplantation of mouse embryos in vitro. J Exp Zool. 1978;206:73–80. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402060108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hooper K, Lane M, Gardner DK. Reduced oxygen concentration increased mouse embryo development and oxidative metabolism. Theriogenology. 2001;55:S334. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westrom L, Mardh PA, Mecklenburg CV, Hakansson CH. Studies on ciliated epithelia of the human genital tract. II. The mucociliary wave pattern of fallopian tube epithelium. Fertil Steril. 1977;28:955–61. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)42798-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foo JY, Lim CS. Biofluid mechanics of the human reproductive process: modeling of the complex interaction and pathway to the oocytes. Zygotes. 2008;16:343–54. doi: 10.1017/S0967199408004899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blake JF, Vann PG, Winet H. A model of ovum transport. J Theor Biol. 1983;102:145–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(83)90267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gopichandran NJ, Leese HJ. The effect of paracrine/autocrine interactions on the in vitro culture of bovine preimplantation embryos. Reproduction. 2006;131:269–77. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cabrera LM, Heo YS, Ding J, Takayama S, Smith GD. Improved blastocyst development with microfluidics and Braille pin actuator enabled dynamic culture. Fertil Steril. 2006;S43.

- 45.Heo YS, Cabrera LM, Bormann CL, Shah CT, Takayama S, Smith GD. Dynamic microfunnel culture enhances mouse embryo development and pregnancy rates. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:613–22. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swain JE, Smith GD. Advances in embryo culture platforms: novel approaches to improve preimplantation embryo development through modifications of the microenvironment. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:541–57. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]