Abstract

Introduction

Drug delivery systems could induce cellular toxicity as side effect of nanomaterials. The mechanism of toxicity usually involves DNA damage. The comet assay or single cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE) is a sensitive method for detecting strand damages in the DNA of a cell with applications in genotoxicity testing and molecular epidemiology as well as fundamental research in DNA damage and repair.

Methods

In the current study, we reviewed recent drug delivery researches related to SCGE.

Results

We found that one preference for choosing the assay is that comet images may result from apoptosis-mediated nuclear fragmentation. This method has been widely used over the last decade in several different areas. Overall cells, such as cultured cells are embedded in agarose on a microscope slide, lysed with detergent, and treated with high salt. Nucleoids are supercoiled DNA form. When the slide is faced to alkaline electrophoresis any breakages present in the DNA cause the supercoiling to relax locally and loops of DNA extend toward the anode as a ‘‘comet tail’’.

Conclusion

This article provides a relatively comprehensive review upon potentiality of the comet assay for assessment of DNA damage and accordingly it can be used as an informative platform in genotoxicity studies of drug delivery systems.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, Drug Delivery, Genotoxicity, Comet Assay, Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis, DNA

Introduction

The human genome is stably exposed to agents that damage DNA. Mechanisms that damage DNA and lead to a perplexing array of DNA lesions are harmful to the human genome and also cancer development. However, acute effects arise from disturbed DNA, halt cell-cycle progression and causes cell death. So induction of DNA damage in cancer cells can be recognized as a therapeutic strategy for killing cancer (Bohr 2002; Fenech 2010) . Three main mechanisms, which induce DNA damage are (1) environmental agents such as ultraviolet light (UV) (2) normal cellular metabolism products which vocalize a continuous source of damage to DNA accuracy ; and (3) chemical agents which bond to DNA and tend to cause spontaneous disintegration of DNA (Hoeijmakers, 2001). Recently drug delivery technologies are used for in vitro cancer therapy studies and nanoparticles are used vastly for this purpose (Ahmad et al. 2010; Alexis et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2010; Rahimi et al. 2010). So, the risk of human, in particular DNA exposure to these materials is rapidly increased and reliable toxicity test systems are urgently needed. Currently, nanoparticle genotoxicity testing is based on in vitro methods established for hazard characterization of chemicals (Donner et al., 2010, Fubini et al., 2010, Landsiedel et al., 2010, Warheit and Donner, 2010). Comet assay is one of the important and well applied in vitro methods in genotoxicology and DNA damage studies. It is an in situ method in which embedded cell on agarose base is lysed and electrophoresed on neutral or alkaline conditions. Acridine orange/ethidium bromide is used for staining of its DNA. Comet metaphor which is risen from astronomy and visually appropriate image obtained with this technique looks like a ‘‘comet” with a distinct head consisting of intact DNA, and a tail including damaged or broken pieces of DNA (Collins et al. 2008; Fucic 1997; Collins et al. 1997; Liao et al. 2009). The comet assay developed as microgel electrophoresis technique for the first time (Ostling and Johanson, 1984). In this technique, embedded cells in agarose gel were placed on a microscope slide. They are lysed by detergents and high salt treatment and the released chromatin is electrophoresed under neutral conditions (pH of 9.5). DNA then is stained with a fluorescent dye (ethidium bromide), resulting a comet with head and tail. Two versions of Comet assay are currently in use; one introduced by Singh et al known as the ‘‘single cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE)’’ technique (Singh et al., 1988), in which alkaline electrophoresis is used (pH.13) for analysis of DNA damage and, is capable of detecting alkali labile sites and DNA single-strand breaks in individual cells. However many investigators refer to this method as the ‘‘Comet assay’’. Subsequently, Olive et al developed versions of the neutral technique of Ostling and Johanson, with minor changes including lysis in alkali treatment followed by electrophoresis at either neutral or mild alkaline (pH 12.3) conditions (Olive et al., 1990a, Olive et al., 1990b). In comparison with other genotoxicity tests, most important advantages of the comet assay are: ability of the assay for DNA damage identifying at the single cell level, its sensitivity for detecting low levels of DNA damage, requirement of small numbers of cells per sample, its ease of application, low cost, flexibility of the assay as it can be used to evaluate various types of DNA damage, modifiability for adaptation to a variety of experimental requirements (Olive et al., 1990b) and need of the short time period for performing the assay as compared. However the fact that it is successful at demonstrating DNA damage is enough to justify its use in many studies to investigate DNA damage and repair in a wide range of tumor cells with a variety of DNA-damaging agents and it is no wonder that the comet assay has been used in a wide variety of the toxicity studies (McKenna et al., 2008, Karlsson, 2010, Eskandani et al., 2010). However here, we present an overview of comet assay as one of the toxicity test methods for nanoparticle’s risk assessment.

The SCGE methodology

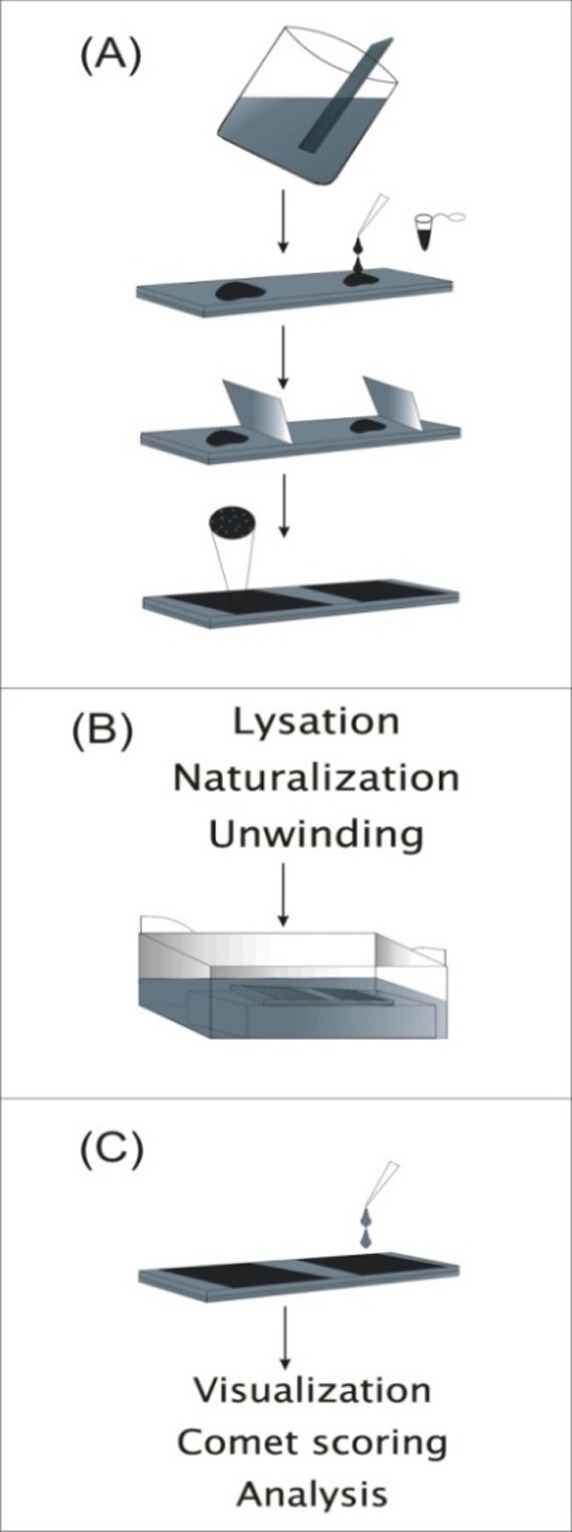

The basic procedure of comet assay was described in detail previously (Olive et al., 1990a, Olive et al., 1990b, Phillips and Arlt, 2009, Singh et al., 1988). As schema views, cells are mixed with 0.5% low-melting point agarose and then placed on a microscope slide pre-coated with 1% normal agarose. When the agarose has solidified, an additional layer of agarose is added. The last layer eliminates in some described SCGE method. Then, the cells are lysed in a detergent solution for 1-14 h. To allow the DNA unwinding, the slides are put into an alkaline or neutral buffer in an electrophoresis chamber for 20 min and then the electrophoresis is carried out. Then electrophoresis slides are rinsed with neutralization buffer or PBS and cells are stained with a fluorochrome dye (Fig.1.).

Fig.1.

Schematic images to represent the procedure of the alkaline comet assay. A shows slide preparation. B panel shows cell lysation, Unwinding and micro electrophoresis. C shows comet visualization and scoring procedures.

Cell suspension preparation

Since the comet assay is designed to evaluate DNA damage in individual cells, clearly the cells or tissues for their evaluation will need to be assayed in a way that allows distinction between the cells. Virtually any eukaryotic cell can be processed for the analysis of DNA damage using this assay. The existence of various methods for generating single cell suspensions is documented in papers covering a wide range of biological fields. The obvious concern for measuring DNA damage and rejoining strand break in tissues from animal or clinical samples is that the samples should be isolated and processed without allowing additional repair or creating additional strand breaks (Rojas et al., 1999).

a) Whole Blood: 75 µL of LMPA (0.5%; 51ºC) mixed with 5-15 µL heparinized whole blood is added to the pre-coated slide. It is possible that as described in hematology procedure addition of equal amount of 0.5% LMPA, blood be diluted with PBS. (DMSO is added in the lysing solution to scavenge radicals generated by the iron released from hemoglobin when whole blood or animal tissues are used. Therefore, it is not needed for other situations)

b) Monolayer and suspend Cultures: In the monolayer types of cultured cells, the media must be removed and 0.005% Trypsin is added to detach the cells from the flask surface at 37° C for 5 minutes. Trypsination is omitted in the suspend method. (Very low concentration of Trypsin (0.005%) is used because higher concentrations increase DNA damage.) Then equal amount of medium (with FBS) is added to quench Trypsin. The suspend cells is centrifuged (900g, 6 min) and supernatant is removed. Sequentially, very small amount of PBS is added to sediment cells. So ~10,000 cells in 10 µl or less volume per 75 µl LMPA is dissolved and the process is continued accordingly.

Slide preparation

In the slide preparation the aim is to obtain uniform gels sufficiently to ensure easily visualized comets with minimal background noise. For this purpose, a layer of agarose is prepared by dipping a fully frosted and chilled microscope slide in to high melting point agarose (formation of flat layer of agarose on the slide surface is vital for imaging and for avoiding to miss-focusing because of multi-surface gel features ). However after cleaning the other side of the slide, it is vital to solidify quietly agarose-surfaced slide. Then, the cells are suspended in low-melting point (LMP) agarose at 37º C are dropped on first solidified agarose layer. An appropriate sized coverslip is used to flatten out each molten agarose layer, and the slides are often chilled during the process to enhance gelling of the agarose. The important parameters for ensuring a successful analysis are the cells concentrations in the agarose for avoiding significant proportion of overlapping comets, especially at high rates of DNA migration, and the concentration of the agarose. Higher agarose concentrations can affect the extent of DNA migration.

Viability Assay

Before cells preparation to comet assay, the minimum viability required of the cells must be approved. For this purpose some easy and comfortable methods such as viability assay using Trypan blue dye and MTT assay were described in previous papers (Fitzgerald and Hosking, 1982, Plumb, 2004, Stoddart, 2011, Supino, 1995). In the simple viability assay, 10 µL of at least 10 6 cells/ml is placed in a microcentrifuge tube and consequentially 10 µL of Trypan blue dye is added to the tube. After about two minutes a drop of the prepared cells is placed on microscopic slides and a coverslip is put on the cells. 100 cells per each slide are scored in the final step and the number of viable cells (shiny) versus dead cells (blue) is recorded. (If the rates of viable cells become lower than 80%, cell preparation must be repeated AGAIN).

Cell lysis and Alkali (pH > 13) unwinding

After the gel containing cells has solidified, the slides are dipped in a lysis solution consisting of high salts and detergents generally for at least 4 h. There are not many significant differences among the various alkaline lysis methods, all of which employ high salt/detergent lysis for a variable period (1–24 h). The most known reagent of the lysis solution that has been used includes 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 10 mMTris, pH 10. However, in rare some cell types may require the second detergent for complete lysis, and this is based on case by case. To maintain the stability of the agarose gel, lysis solution is chilled prior to use. The liberated DNA can be incubated with proteinase K (PK) between lysis and alkali unwinding to remove residual proteins or probed with DNA repair enzymes/antibodies to identify specific classes of DNA damage (e.g. oxidative damage). In order to avoid more DNA damages, all steps must be carried out in dark room. However, after lysis of the cells the slide must be washed three times in 0.4 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 (Naturalization buffer) at 4°C. Prior to electrophoresis to formation of a comet picture and also production of single-stranded DNA, the slides are incubated in alkaline (pH > 13) electrophoresis buffer, knowing alkali unwinding step. The alkaline solution developed by Singh et al. consists of 1 mM EDTA and 300 mM sodium hydroxide, pH > 13.0 (Singh et al., 1988).

Electrophoresis, Comet staining and scoring

After alkali unwinding, all chromatin, especially the single-stranded DNA is subjected in the thin layer gel to electrophoresis under alkaline conditions to form comets. During electrophoresis, the alkaline buffer pH, which is used during alkali unwinding has same pH > 13 buffer which is used during alkali unwinding. Since DNA migration of only a minor distance is required in the comet formation, thus only very short electrophoresis running time (10–20 min) and low voltages (0.5–5.0 V/cm) are needed. However comet electrophoresis differs from conventional DNA electrophoresis. The electrophoretic conditions are 25 V and 300 mA.

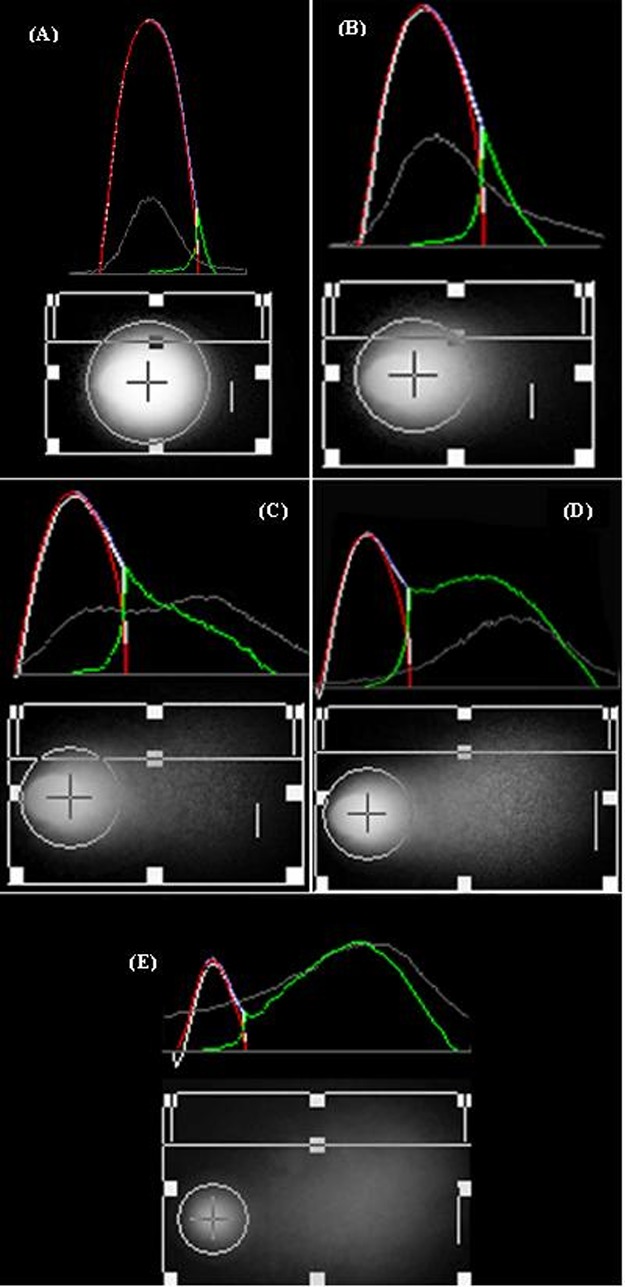

However, the optimal voltage/amperage depends on the extent of DNA migration seen in the control cells, and range of migration under evaluation among the treated cells. After electrophoresis, the slides should be stained with 25μl of 0.6 μM Ethidium Bromide for visualization of the comet and followed by slipping a coverslip on the vision window. Then comets are detectable with the fluorescent microscope. (Fig.2.) However, Nadin et al. carried out for first time a procedure to stain the comet with silver to avoid toxicological effects of Ethidium bromide as a carcinogen material. Surprisingly, they contended that their silver staining method significantly increases the sensitivity/reproducibility of the comet assay in comparison with the fluorescent staining that is very questionable (Nadin et al., 2001).

Fig. 2.

Comet images ×40 taken by fluorescent microscope with Nikon camera; Acquisition with Photoshop CS4.Comet images evaluated by CASP software and categorized from A - E to show grade ‘0’ to ‘4’ with red and green curve for head and tail DNA, respectively.

However, 100 cells is always selected randomly for the analysis of comet quantity and analyzed under fluorescent microscope by quantifying the DNA damage (%tail DNA/head DNA) through using softwares analyzing comet image such as CASP & Comet IV, or manually with consideration and classification of the comet with damage range from 0 to 4 using following formula. In this formula DD is the rate of the DNA damage, whereas n0- n4 are the type of the comet including 0-4 types. Finally, Σ is the sum of the scored comet including types 1-4 also '0' type comets.

DD = (0n0 + 1n1 + 2n2 + 3n3 + 4n4)/ (Σ/100)

Nanoparticle-based drug delivery

Nanomaterial is a material which has the minimum length<100 nm in size. They have many different forms such as tubes, rods, wires or spheres, with more complicated structures such as nano-onions and nanopeapods (Cheng, 2004, Kokubo et al., 2003, Pramod et al., 2009). Even though, they have novel physico-chemical properties and medical applications, such as faming as drug delivery machine directed specific drugs to the site of tumors, they also may be responsible for unfavorable biological side effects (Dhawan and Sharma, 2010, Singh et al., 2009, Jang et al., 2010, Sohaebuddin et al., 2010). Biodegradable polymers have been studied over the past few decades for the construction of drug delivery systems, in view of their applications and limitation in controlling the release of drugs, stabilizing adjective molecules (e.g., peptides, proteins, or DNA) from degradation, and site-specific drug targeting (Dolatabadi et al., 2011). Additionally, a vesicular system in which the drug is encapsulated by a polymer membrane is nanocapsules, whereas nanospheres are matrix systems in which the drug is physically dispersed. Typically, in the drug delivery systems the drug can be dissolved, entrapped, absorbed, attached and/or encapsulated into/onto a nano-matrix (Dolatabadi et al., 2011). Depending on the method of preparation nanoparticles, nanospheres, or nanocapsules can be constructed in order to possess different properties and release characteristics for the best delivery or encapsulation of the therapeutic agent (Beaux et al., 2008, Yang and Webster, 2009, Hammond, 2011). Some characteristics having importance for drug delivery using nanoparticles are the properties of the nanoparticle surface, drug loading ability, drug releasing preference and finally the properties of the nanoparticle in target therapy (Suri et al., 2007). Also, the size can influence drug loading, drug release and stability of nanoparticles. The size of the nanoparticles determine the in vivo biological fate, toxicity, and targeting. Indeed, nanoparticles can be recognized by the host immune system as antigen and cleared by phagocytes from the blood circulation, when they used intravenously (Li and Liu, 2004, Petros and DeSimone, 2010).

Nanoparticle hydrophobicity (e.g. opsonins) determines the level of blood components that bind to the surface of nanomaterial, yet the size of the nanoparticle has vital role in drug delivery. To increase the success rate of drug targeting, it is necessary to minimize the opsonization in contrast, prolonging the in vivo circulation of nanoparticles (Owens and Peppas, 2006). However, by coating nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymers/surfactants or formulating nanoparticles with biodegradable copolymers owning hydrophilic characteristics, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyethylene oxide, polyoxamer, poloxamine, and polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) the time of intravenously circulating increases , hence the impressments of the nano-drug delivery system become higher (Arayne et al., 2007). On the other hand, a successful nano delivery system should have a high drug-loading capacity. Also, it is revealed that when the macromolecules, drugs or protein are used in nanoparticles, they show the greatest loading efficiency in the isoelectric point of the nanoparticles near to the pI of consignments (Calvo et al., 1997). Indeed, the other factor that defines the efficiency of the drug delivery system is the potentiality of nano-carrier in drug releasing ratio. It is demonstrated that the drug release rate depends on some physico-chemical features of both drugs and nanoparticle including drug solubility, desorption of the surface-bound or absorbed drug, nanoparticle matrix erosion or degradation, drug diffusion through the nanoparticle matrix and finally the combination of erosion and diffusion processes. Hence, solubility, diffusion, and biodegradation of the particle matrix control the release process (Zhang et al., 2003, Frank et al., 2005, Efentakis et al., 2007). Aside from these features, the most important aspect of drug delivery systems is targeted properties of the nanoparticles. Targeted delivery can be actively or passively achieved. In active targeting, therapeutic agent or carrier system conjugates to a tissue or cell-specific ligand (Lamprecht et al. 2001). But in passive, targeting is achieved by incorporating the therapeutic agent into a macromolecule or nanoparticle that reaches the target organ. However, the most important view in drug delivery systems is the non-toxicity of the nanoparticles having used in targeted delivery to raise the efficiency of nonmaterial therapy and also to decrease the biological side effect of such intelligent and targeted nano-structure materials.

Toxicity of advanced materials

There are some limited information indicating that nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (Park and Park, 2009, Reddy et al., 2010, Neubauer et al., 2008). However, some of these investigations failed to see minor cellular changes that may arise at lower concentrations, which may not result in cell demise but could relate to human health risks. Indeed, due to drug delivery purposes nanoparticles joins also to physico-chemical features such as metal contaminants and charged surfaces, and may well have unpredictable genotoxic properties. Due to the fact that genotoxins can cause genetic alterations and many cancers in the absence of cell death, DNA is the most important macromolecule that mostly faces this overlooking. DNA damage could not only trigger cancer development, but also can have an impact on fertility and the health. Hence, a main area presiding over health risk assessment of new pharmaceuticals and chemicals agents such as nanoparticle is genotoxicology. As a result, genotoxicity testing and evaluation of the carcinogenic or mutagenic potential of new substances is a main part of preclinical safety testing of novel pharmaceutical nanoparticles. Nanoparticles can affect mechanisms leading to penetration of the nanomaterials to the cells and subsequently the nucleus, inducing DNA damage. Nanomaterials may be able to penetrate directly into the nucleus through diffusion across the nuclear membrane (if they are small enough), transport through the nuclear pore complexes, and finally may become surrounded in the nucleus following mitosis when the nuclear membrane is dissolved during cell division and then reorganized in each next generation cells (Feldherr 1998; Macara 2001; Moroianu 1999). If the nanomaterials locate within the nucleus, they will then interact directly with DNA molecule or DNA-related proteins and may cause physical damage to the intelligent and inheritance material.

Due to the anticipated development in the field of nanomaterials, trustworthy toxicity of these nanoscale agents, based on drug delivery systems, and the increasing risk of the exposure to nanomaterials must have been investigated. Therefore nowadays a meticulous defy is to declare safety and usefulness for nanoscale biomedical systems to characterize their toxicological properties requiring unique measurement protocols and criteria for healthful versus harmful exposure results.

Comet assay and genotoxicity of nanoparticles used in drug delivery system

Revealing of the genotoxicity and cytotoxicity properties of nanoparticles based drug delivery systems on the different parts of cells may enhance their usefulness in targeting therapeutic approaches in many aspects. Ever since many techniques have been developed to investigate toxicological effect of nanoparticles, genomically. Additionally, cellular in vitro poisonousness assays such as ROS production assays, cell viability assays and cell stress assays (studying the protein/gene expression, inflammatory markers, Cell visualization, internalization, and organelle interaction) have been used to evaluate toxicity of nanomaterial (Jones and Grainger, 2009). Genotoxicity tests detect DNA damage with some special techniques such as comet assay, Chromosome aberration test, HPRT forward mutation assay, g-H2AX staining, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine DNA adducts, micronucleus test and Ames test (Singh et al., 2009). In order to evaluate genotoxicity of nanomaterials, the most often used technique is the single-cell gel electrophoresis assay (Comet test). As best our knowledge with 20 studies, 14 have positive result, and 6 the negative outcome. Comet assay has been used for evaluation of the genotoxicity of some nanoparticles included in drug delivery systems such as single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT), C60 fullerenes, titanium dioxide (TiO2), Carbon black particles, and other nanoparticles that are described in table 1. Briefly, some nanoparticles that their genotoxicity evaluated with comet assay describe flowing.

Table 1. Genotoxicity evaluation of nanoparticles that have use in drug delivery systems with comet assay.

| Reference | Result | In vivo/In vitro | Properties | Material |

| (Dhawan et al., 2006) | Comet positive | Human lymphocytes | Aqueous suspensions of colloidal C60 fullerenes (‘‘EtOH/nC60 suspensions’’) and (‘‘aqu/nC60 suspensions’’) | Fullerenes |

| (Kisin et al., 2007) | Comet positive | V79 cells | Size 0.4 -1.2 nm, length of 1–3 mm surface area of 1040 m2/g, 99.7 wt% carbon ,0.23 wt% iron levels | Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) |

| (Wang et al., 2007) | Comet positive | Human B-cell lymphoblastoid WIL2-NS cells | (99% purity, sonicated, size distribution 6.57 nm: 100%, 8.2 nm: 80.4% and 196.5 nm: 19.4% | Titanium dioxide (TiO2) |

| (Nakagawa et al., 1997) | Comet positive After irradiation | L5178Y mouse lymphoma cells | Average size 21 nm, particles suspended in EBSSfpr irradiation | Titanium dioxide P25 |

| (Mroz et al., 2008) | Comet positive | A549 (a type II alveolar-like human lung adenocarcinoma cell line) | Primary diameter 14 nm, suspended at 100 mg/mL in serum-free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and sonicated for 20 min | Carbon Black |

| (Gurr et al., 2005) | Comet positive | Human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B, cultured in LHC-9 medium) | Anatase TiO2 particles, size 10 and 20 nm, sterilized, suspended in sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mg/mL). | Titanium dioxide (TiO2) |

| (Jacobsen et al., 2007) | Comet positive | FE1 MutaTMMouse lung epithelial cells | Printex 90, size 14 nm, surface area: 295 m2/g, sonicated using a Branson Sonifier S-450D in 5 mL medium | Carbon Black |

| (Dunford et al., 1997) | Comet positive | MRC-5 human fibroblasts | Size 20–50 nm, extracted from over-the-counter sunscreens, determines their anatase and rutile by X-ray diffraction. ZnO contained in some samples. | Titanium dioxide (TiO2) |

| (Zhong et al., 1997) | Comet negative | V79 Chines hamster lung fibroblasts and in Hel 299 human embryonic lung fibroblasts | Particle size 37 nm (99% carbon) autoclaved, sonicated in MEM | Carbon black |

| (Wang et al. 2007b; Wang et al. 2007c) | Comet negative | WIL2-NS human B-cell lymphoblastoid cells | 99% purity, particle size distribution 7.21 nm, 100%; 9.08 nm, 71.4% and 123.21 nm, 28.6% suspended in culture medium vortexed and sonicated for 10 min in an ultrasonic water bath. | SiO2 |

| (Barnes et al., 2008) | Comet negative | 3T3-L1 fibroblasts | Size 30,80,400 nm, characterized with TEM and DLS | Amorphous silica |

| (Pacheco et al., 2007) | Comet positive | MCF-7 | The LUDOX CL colloidal silica suspension in water was adjusted to a pH of 7 with 0.1mol/L NaOH | Amorphous silica |

| (Gopalan et al., 2009) | Comet positive | PBL; human sperm cells | Size 40–70 nm | Anatase TiO2 and ZnO |

| (Karlsson et al., 2008) | Dose-dependent increase in DNA damage induced byTiO2>carbn nanotubes. | A549 type II lung epithelial cells | TiO2 particles (a mix of rutile and anatase) | TiO2, carbon notubes |

| (Jin et al., 2007) | Comet negative | A549 cells | Size 50 nm | SiO2 doped with luminescent dyes (RuBpy and TMR) |

| (Hoshino et al., 2004) | Increase in comet tail length after 2 h, but did not persist at 12 h | WTK1 cells | Size 18.03±6.76 nm | QD-COO |

| (Jacobsen et al., 2008) | C(60) and SWCNT did not increase the level of strand breaks SWCNT and C60 are less genotoxic than CB | FE1Muta Mouse lung epithelial cell line | -99.9% pure [0.7 nm] -0.9–1.7 nm diameter,1 mm length -14 nm | - C60 - SWCNT - Carbon Black (CB) |

| (Kafil and Omidi, 2011) | Somewhat comet positive | A431 cells | linear and branched polyethylenimine | Cationic polymer |

| (Omidi et al., 2008) | Comet negative | A549 cells | Oligofectamine (OF) | Cationic lipids |

Cationic polymers and lipids

Cationic polymers (at physiological pH; polycations or polycation-containing block copolymers), are a series of polymers which can be made of a variety of polymers including polyethyleneimine (PEI), chitosan, Poly ethylene glycol-based polymers. Cationic polymer can be combined with polynucleic acids (e.g., DNA or RNA) to form a particulate complex, such as interpolyelectrolyte complexes (IPECs) or block ionomer complexes (BICs) and so, is able to transfer the genes into the targeted cells (El-Aneed, 2004). Polyethylenimines (PEIs) are series of synthetic cationic polymers, well-known as an efficient non-viral nucleic acid vector bearing a high cationic charge density which provides to condense and compact the carried DNA into complexes (Boussif et al., 1995). Different types of polyethylenimine (PEI), viz., branched (25 and 800kDa) and linear (25kDa), have been successfully used as transfection agents (Demeneix et al., 1998). The most other important series of polymeric based nanoparticles that have application in drug carrier and gene therapy systems are cationic lipids. It is composed of three basic domains: a positive charged head group, a hydrophobic chain, and a linker which joins the polar region to the non-polar (Gao and Hui, 2001). The polar and hydrophobic domains of cationic lipids may have remarkable effects on both transfection and toxicity levels. The most obvious difference between cationic polymers and cationic lipids is in that cationic polymers do not contain a hydrophobic moiety and are completely soluble in water (Elouahabi and Ruysschaert, 2005). The straight facing of the cationic polymers and lipids are sufficient to the host genome and vast usage of the mentioned polymers in gene/drug delivery to the researchers that consider their side cell/geno-toxcicity effect. Recently Omidi et al evaluated genotoxic impacts of linear and branched polyethylenimine nanostructures in A431 cells (Kafil and Omidi, 2011). Using comet assay, they reported that these types of the nanostructure induce DNA damage to some degree. In addition, they evaluated the genotoxicity of Oligofectamine (OF) nanosystems – a type of the cationic lipid – in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Surprisingly, they found no genomic damage detected by the comet assay (Omidi et al., 2008).

Fullerene

A fullerene is in the form of a hollow sphere, ellipsoid, or tube that is composed completely of carbon. Fullerenes structurally are similar to graphite, which is composed of stacked graphene sheets of linked hexagonal rings, yet they may also contain pentagonal or sometimes heptagonal rings. Spherical fullerenes also called buckyballs and cylindrical ones are called carbon nanotubes or buckytubes. Fullerenes attract attention due to their radical scavenging and anti-oxidant properties. Currently they are used in targeted drug delivery, polymer modifications, energy application and cosmetic products (Wang et al., 2004).

C60 fullerene

A Buckminsterfullerene or C60 fullerene (C60) is a spherical molecule and the smallest one with the formula C60 (Wang et al., 2004). It is used in some studies as targeted drug delivery carrier (Aschberger et al., 2010). To evaluate the genotoxic effects of the C60 fullerenes, Dhawan et al (2006) assessed C60 fullerenes free of toxic organic solvents prepared by either ethanol to water solvent exchange (‘‘EtOH/nC60 suspensions’’) or by mixing in water (‘‘aqu/nC60 suspensions’’) using the comet assay on human lymphocytes. Results showed a strong correlation between the genotoxic response and nC60 concentration, and also genotoxicity observed at concentrations as low as 2.2 mg/L for aqu/nC60 and 4.2 mg/L for EtOH/nC60 (Dhawan et al., 2006).

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)

Carbon nanotubes are nanomaterials made up of thin graphitic sheets formed tubular structure. Two main types of carbon nanotubes including single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) with a single tube of carbon (0.4–2 nm) and multiple-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) composed of several concentric tubes (2–100 nm) (Ji et al., 2010). CNTs have some applications in nanomedicine: they provide appropriate substrate for growth of cells in tissue renewal; they can also be used as nanocarriers for a diversity of therapeutic or diagnostic agents, and finally as vectors for gene transfection (Chen et al., 2006). Consequently, many studies have been performed concerning the toxicity of these nanoparticles used with different techniques. Kisin et al. examined the genotoxicity of SWCNT with diameters between 0.4 and 1.2 nm in V79 cells with comet assay technique. Results showed the significant DNA damage after only 3h of incubation with 96 mg/cm2 of SWCNT (Kisin et al., 2007).

Titanium dioxide (TiO2)

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is one of the promising materials being considered for various applications. Usually, it is used as a material in the memristor, a new electronic circuit element and other applications related to solar cells (Sohaebuddin et al., 2010, West and Halas, 2003). Additionally the use of TiO2 as drug carrier in nanomedicine has been considered in different aspects. Recently, the effect of textural specifications of nanoporous TiO2 matrices was assessed on the drug delivery activities by M. Signoretto et al. They demonstrated that nanoporous can be used as matrix for the continued release of a drug; they showed also a close association between the pores dimension of TiO2 and the drug release (Signoretto et al., 2011). In addition, several investigations have been performed on the genotoxicity effect of TiO2 on various cell lines. Wang, Jing J et al evaluated the genotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles on cultured human B-cell lymphoblastoid WIL2-NS cells with comet assay procedure. At a concentration of 65 mg/mL, the nanoparticles induced significant genotoxicity after an exposure of 24 h in cultured human B-cell lymphoblastoid WIL2-NS cells (Wang et al., 2007). Also in another study Nakagawa et al. reported comet positive results in L5178Y mouse lymphoma cells exposed to Titanium dioxide P25 (Nakagawa et al., 1997).

Carbon Black

Carbon Black (CB) is a family of small particles consisting carbon fractal aggregates. Carbon black is chemically and physically distinct from soot and black carbon. The basic building units of CB are nano-sized particles formed by stacked graphene layers exhibiting random orientations about the staking axis and also parallel to the layers in translation (turbostratic structure) (Sanjinés et al.). Due to their electrical properties, carbon blacks are widely used as conducting fillers in polymers. CB/polymer composites have wide range of applications including graded semiconductors for optoelectronic applications, conducting electrodes, solid electrolytes for batteries, anti-reflection coatings, room temperature gas sensors, electrical switching devices, etc (Chung, 2004). The potential use of carbon black for delivery of molecules was reported by Prerona Chakravarty in to the cell, in 2010. Their initial results suggest that interaction between the laser energy and carbon black nanoparticles may generate photoacoustic forces by chemical reaction in order to create transient holes in the membrane for intracellular delivery (Chakravarty et al., 2010). Also in the study about the genotoxic effect of carbon black with comet assay, N.R. Jacobsen reported 75 mg/mL particles induced in FE1 MutaTM mouse lung epithelial cells within 3 h, a significant increase in DNA strand breaks(p = 0.02) detected in the alkaline Comet assay (Jacobsen et al. 2007). In another study, Mroz et al. reported positive comet assay result of Carbon black in A549 human adenocarcinoma cells (Mroz et al., 2008).

Silica nanoparticles

The non-metal oxide of silicon (silica) exists in two main forms; amorphous, which has no long range order, and crystalline, where oxygen and silicon atoms are in a fixed, ordered periodic arrangement (Greenberg et al., 2007). Mesoporous silica is a form of silica which is a recent development in nanotechnology. The most common types of mesoporous nanoparticles are MCM-41 and SBA-15, their main component is amorphous silica. Research continues on the particles, which have applications in catalysis, drug delivery and imaging. Many studies have been performed about use of silica nanoparticles as drug delivery vehicles (Vallet-Regi et al. 2007; Vivero-Escoto et al. 2010; Trewyn et al. 2008). For example, Yufang Zhu et al reported the potential of PEGylated hollow mesoporous silica (HMS-PEG) nanoparticles as drug vehicles for drug delivery (Zhu et al., 2011). Recently, three surfactant-templated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (Surf@MSNs) were developed as anticancer drug delivery systems. The Surf@MSNs exhibit the high drug (surfactant) loading capacities, the sustained drug (surfactant) release profiles and the high and long-term anticancer efficacy (He et al., 2010).Crystalline silica has been shown to be both cytotoxic and genotoxic on in vitro testing by some studies (Fanizza et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007b). Other groups have found that high doses of crystalline silica are necessary to produce detectable genotoxicity using the single cell gel electrophoresis (Cakmak et al., 2004). Also in the other study performed by Barnes Clifford A. et al the comet assay results indicated no significant genotoxicity at either 4 or 40 μg/ml doses for any of the tested amorphous silica samples in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts (Barnes et al., 2008). Alternatively, this study is in contrast to the results of Pacheco et al. They used MCF-7 as model systems for genotoxicity testing with comet assay (Pacheco et al., 2007).

Conclusion

Based on the best of our knowledge, this article is the first review on the application of comet assay in genotoxicity of nanoparticles used in the drug delivery systems. Application of the advanced nanomaterials in wide range of the biomedical researches and applications such as drug delivery system compel the researcher to work within these materials discreetly because of their probable toxicity effects on the inherent material. However risk appraisal of nanomaterials, challenges some of the present DNA damage assessment methods due to the unique nature of material at nano-scale. Considering large number of studies on the genotoxic effect of the nanomaterials and high potential of comet assay in precise DNA damage detection, using alkaline single cell gel electrophoresis is a very useful tool for diagnosis of the nanoparticle genotoxicity that is used in drug delivery system and also are highly recommended to reduce side effect of these types of therapies.

Ethical Issues

None to be declared.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miss Ilghami for her kind editing of this work. Also, we acknowledge Research Center for Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology (RCPN) of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

References

- Arayne Ms, Sultana N and Qureshi F . 2007 Review: nanoparticles in delivery of cardiovascular drugs. Pak J Pharm Sci, 20(4), 340-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschberger K, Johnston Hj, Stone V, Aitken Rj, Tran Cl, Hankin Sm, et al. 2010 Review of fullerene toxicity and exposure--appraisal of a human health risk assessment, based on open literature. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 58(3), 455-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes Ca, Elsaesser A, Arkusz J, Smok A, Palus J, Lesniak A, et al. 2008 Reproducible comet assay of amorphous silica nanoparticles detects no genotoxicity. Nano Lett, 8(9), 3069-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaux Mf, Mcilroy Dn and Gustin Ke . 2008 Utilization of solid nanomaterials for drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv, 5(7), 725-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussif O, Lezoualc'h F, Zanta Ma, Mergny Md, Scherman D, Demeneix B, et al. 1995 A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 92(16), 7297-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak Gd, Schins Rp, Shi T, Fenoglio I, Fubini B and Borm Pj . 2004 In vitro genotoxicity assessment of commercial quartz flours in comparison to standard DQ12 quartz. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 207(2), 105-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo P, Remunan-Lopez C, Vila-Jato Jl and Alonso Mj . 1997 Chitosan and chitosan/ethylene oxide-propylene oxide block copolymer nanoparticles as novel carriers for proteins and vaccines. Pharm Res, 14(10), 1431-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty P, Qian W, El-Sayed Ma and Prausnitz Mr . 2010 Delivery of molecules into cells using carbon nanoparticles activated by femtosecond laser pulses. Nat Nanotechnol, 5(8), 607-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tam Uc, Czlapinski Jl, Lee Gs, Rabuka D, Zettl A, et al. 2006 Interfacing carbon nanotubes with living cells. J Am Chem Soc, 128(19), 6292-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Md . 2004 Effects of nanophase materials (< or = 20 nm) on biological responses. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng, 39(10), 2691-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Ddl . 2004 Electrical applications of carbon materials. Journal of Materials Science, 39(8), 2645-2661 [Google Scholar]

- Demeneix B, Behr J, Boussif O, Zanta Ma, Abdallah B and Remy J . 1998 Gene transfer with lipospermines and polyethylenimines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 30(1-3), 85-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan A and Sharma V . 2010 Toxicity assessment of nanomaterials: methods and challenges. Anal Bioanal Chem, 398(2), 589-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan A, Taurozzi Js, Pandey Ak, Shan W, Miller Sm, Hashsham Sa, et al. 2006 Stable colloidal dispersions of C60 fullerenes in water: evidence for genotoxicity. Environ Sci Technol, 40(23), 7394-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolatabadi JE, Mashinchian O, Ayoubi B, Jamali Aa, Mobed A, Losic D, et al. 2011 Optical and electrochemical DNA nanobiosensors. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 30(3), 459-472 [Google Scholar]

- Donner M, Tran L, Muller J and Vrijhof H . 2010 Genotoxicity of engineered nanomaterials. Nanotoxicology, 4345-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dunford R, Salinaro A, Cai L, Serpone N, Horikoshi S, Hidaka H, et al. 1997 Chemical oxidation and DNA damage catalysed by inorganic sunscreen ingredients. FEBS Lett, 418(1-2), 87-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efentakis M, Pagoni I, Vlachou M and Avgoustakis K . 2007 Dimensional changes, gel layer evolution and drug release studies in hydrophilic matrices loaded with drugs of different solubility. Int J Pharm, 339(1-2), 66-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Aneed A. 2004. An overview of current delivery systems in cancer gene therapy. J Control Release 941–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elouahabi A and Ruysschaert Jm . 2005 Formation and intracellular trafficking of lipoplexes and polyplexes. Mol Ther, 11(3), 336-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandani M, Golchai J, Pirooznia N and Hasannia S . 2010 Oxidative stress level and tyrosinase activity in vitiligo patients. Indian J Dermatol, 55(1), 15-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald Mg and Hosking Cs . 1982 Cell structure and percent viability by a slide centrifuge technique. J Clin Pathol, 35(2), 191-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A, Rath Sk and Venkatraman Ss . 2005 Controlled release from bioerodible polymers: effect of drug type and polymer composition. J Control Release, 102(2), 333-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fubini B, Ghiazza M and Fenoglio I . 2010 Physico-chemical features of engineered nanoparticles relevant to their toxicity. Nanotoxicology, 4347-63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gao H and Hui Km . 2001 Synthesis of a novel series of cationic lipids that can act as efficient gene delivery vehicles through systematic heterocyclic substitution of cholesterol derivatives. Gene Ther, 8(11), 855-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan Rc, Osman If, Amani A, De Matas and Anderson D . 2009 The effect of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in the Comet assay with UVA photoactivation of human sperm and lymphocytes. Nanotoxicology, 3(1), 33-39 [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg Mi, Waksman J and Curtis J . 2007 Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon, 53(8), 394-416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurr Jr, Wang As, Chen Ch and Jan Ky . 2005 Ultrafine titanium dioxide particles in the absence of photoactivation can induce oxidative damage to human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicology, 213(1-2), 66-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond Pt . 2011 Virtual issue on nanomaterials for drug delivery. ACS Nano, 5(2), 681-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Shi J, Chen F, Zhu M and Zhang L . 2010 An anticancer drug delivery system based on surfactant-templated mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomaterials, 31(12), 3335-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers Jh . 2001 Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature, 411(6835), 366-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino A, Fujioka K, Oku T, Suga M, Sasaki Yf, Ohta T, et al. 2004 Physicochemical Properties and Cellular Toxicity of Nanocrystal Quantum Dots Depend on Their Surface Modification. Nano Letters, 4(11), 2163-2169 [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen Nr, Pojana G, White P, Moller P, Cohn Ca, Korsholm Ks, et al. 2008 Genotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and reactive oxygen species induced by single-walled carbon nanotubes and C(60) fullerenes in the FE1-Mutatrade markMouse lung epithelial cells. Environ Mol Mutagen, 49(6), 476-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen Nr, Saber At, White P, Moller P, Pojana G, Vogel U, et al. 2007 Increased mutant frequency by carbon black, but not quartz, in the lacZ and cII transgenes of muta mouse lung epithelial cells. Environ Mol Mutagen, 48(6), 451-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Lim Dh and Choi Ih . 2010 The impact of nanomaterials in immune system. Immune Netw, 10(3), 85-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Sr, Liu C, Zhang B, Yang F, Xu J, Long J, et al. 2010 Carbon nanotubes in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1806(1), 29-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Kannan S, Wu M and Zhao Jx . 2007 Toxicity of luminescent silica nanoparticles to living cells. Chem Res Toxicol, 20(8), 1126-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Cf and Grainger Dw . 2009 In vitro assessments of nanomaterial toxicity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 61(6), 438-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafil V and Omidi Y . 2011 Cytotoxic impacts of linear and branched polyethylenimine nanostructures in A431 cells. BioImpacts, 1(1), 23-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson Hl . 2010 The comet assay in nanotoxicology research. Anal Bioanal Chem, 398(2), 651-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson Hl, Cronholm P, Gustafsson J and Moller L . 2008 Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: a comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem Res Toxicol, 21(9), 1726-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisin Er, Murray Ar, Keane Mj, Shi Xc, Schwegler-Berry D, Gorelik O, et al. 2007 Single-walled carbon nanotubes: geno- and cytotoxic effects in lung fibroblast V79 cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A, 70(24), 2071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokubo T, Kim Hm and Kawashita M . 2003 Novel bioactive materials with different mechanical properties. Biomaterials, 24(13), 2161-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsiedel R, Ma-Hock L, Van Ravenzwaay B, Schulz M, Wiench K, Champ S, et al. 2010 Gene toxicity studies on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanomaterials used for UV-protection in cosmetic formulations. Nanotoxicology, 4364-81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li S and Liu X . 2004 [Development of polymeric nanoparticles in the targeting drugs carriers]. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi, 21(3), 495-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenna Dj, Mckeown Sr and Mckelvey-Martin Vj . 2008 Potential use of the comet assay in the clinical management of cancer. Mutagenesis, 23(3), 183-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz Rm, Schins Rp, Li H, Jimenez La, Drost Em, Holownia A, et al. 2008 Nanoparticle-driven DNA damage mimics irradiation-related carcinogenesis pathways. Eur Respir J, 31(2), 241-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadin Sb, Vargas-Roig Lm and Ciocca Dr . 2001 A silver staining method for single-cell gel assay. J Histochem Cytochem, 49(9), 1183-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Wakuri S, Sakamoto K and Tanaka N . 1997 The photogenotoxicity of titanium dioxide particles. Mutat Res, 394(1-3), 125-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer O, Reichhold S, Nersesyan A, Konig D and Wagner Kh . 2008 Exercise-induced DNA damage: is there a relationship with inflammatory responses? Exerc Immunol Rev, 1451-72 [PubMed]

- Olive Pl, Banath Jp and Durand Re . 1990. a Detection of etoposide resistance by measuring DNA damage in individual Chinese hamster cells. J Natl Cancer Inst, 82(9), 779-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive Pl, Banath Jp and Durand Re . 1990. b Heterogeneity in radiation-induced DNA damage and repair in tumor and normal cells measured using the "comet" assay. Radiat Res, 122(1), 86-94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi Y, Barar J, Heidari Hr, Ahmadian S, Yazdi Ha and Akhtar S . 2008 Microarray analysis of the toxicogenomics and the genotoxic potential of a cationic lipid-based gene delivery nanosystem in human alveolar epithelial a549 cells. Toxicol Mech Methods, 18(4), 369-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostling O and Johanson Kj . 1984 Microelectrophoretic study of radiation-induced DNA damages in individual mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 123(1), 291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens De, 3rd and Peppas Na. 2006 Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int J Pharm, 307(1), 93-102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco S, Mashayekhi H, Jiang W, Xing B and Arcaro Kf. 2007. DNA damaging effects of nanoparticles in breast cancer cells. Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

- Park Ej and Park K . 2009 Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory responses induced by silica nanoparticles in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol Lett, 184(1), 18-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros Ra and Desimone Jm . 2010 Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 9(8), 615-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Dh and Arlt Vm . 2009 Genotoxicity: damage to DNA and its consequences. EXS, 9987-110 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Plumb Ja . 2004 Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. Methods Mol Med, 88165-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pramod P, Thomas Kg and George Mv . 2009 Organic nanomaterials: morphological control for charge stabilization and charge transport. Chem Asian J, 4(6), 806-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy Ar, Reddy Yn, Krishna Dr and Himabindu V . 2010 Multi wall carbon nanotubes induce oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. Toxicology, 272(1-3), 11-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas E, Lopez Mc and Valverde M . 1999 Single cell gel electrophoresis assay: methodology and applications. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl, 722(1-2), 225-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjinés R, Abad Md, Vâju C, Smajda R, Mionic M and Magrez A. Electrical properties and applications of carbon based nanocomposite materials: An overview. Surface and Coatings Technology, In Press, Corrected Proof.

- Signoretto M, Ghedini E, Nichele V, Pinna F, Crocellà V and Cerrato G . 2011 Effect of textural properties on the drug delivery behaviour of nanoporous TiO2 matrices. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 139(1-3), 189-196 [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Manshian B, Jenkins Gj, Griffiths Sm, Williams Pm, Maffeis Tg, et al. 2009 NanoGenotoxicology: the DNA damaging potential of engineered nanomaterials. Biomaterials, 30(23-24), 3891-914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Np, Mccoy Mt, Tice Rr and Schneider El . 1988 A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res, 175(1), 184-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohaebuddin Sk, Thevenot Pt, Baker D, Eaton Jw and Tang L . 2010 Nanomaterial cytotoxicity is composition, size, and cell type dependent. Part Fibre Toxicol, 722, 722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart Mj . 2011 Cell viability assays: introduction. Methods Mol Biol, 7401-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Supino R . 1995 MTT assays. Methods Mol Biol, 43137-49 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Suri Ss, Fenniri H and Singh B . 2007 Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems. J Occup Med Toxicol, 216, 216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Guo Z-X, Fu S, Wu W and Zhu D . 2004 Polymers containing fullerene or carbon nanotube structures. Progress in Polymer Science, 29(11), 1079-1141 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Jj, Sanderson Bj and Wang H . 2007 Cyto- and genotoxicity of ultrafine TiO2 particles in cultured human lymphoblastoid cells. Mutat Res, 628(2), 99-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warheit Db and Donner Em . 2010 Rationale of genotoxicity testing of nanomaterials: regulatory requirements and appropriateness of available OECD test guidelines. Nanotoxicology, 4409-13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- West Jl and Halas Nj . 2003 Engineered nanomaterials for biophotonics applications: improving sensing, imaging, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Biomed Eng, 5285-92 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang L and Webster Tj . 2009 Nanotechnology controlled drug delivery for treating bone diseases. Expert Opin Drug Deliv, 6(8), 851-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Yang Z, Chow Ll and Wang Ch . 2003 Simulation of drug release from biodegradable polymeric microspheres with bulk and surface erosions. J Pharm Sci, 92(10), 2040-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Bz, Whong Wz and Ong Tm . 1997 Detection of mineral-dust-induced DNA damage in two mammalian cell lines using the alkaline single cell gel/comet assay. Mutat Res, 393(3), 181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Fang Y, Borchardt L and Kaskel S . 2011 PEGylated hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles as potential drug delivery vehicles. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 141(1-3), 199-206 [Google Scholar]