Abstract

Background

In Ontario, Canada, the patient-centred medical home is a model of primary care delivery that includes 3 model types of interest for this study: enhanced fee-for-service, blended capitation, and team-based blended capitation. All 3 models involve rostering of patients and have similar practice requirements but differ in method of physician reimbursement, with the blended capitation models incorporating adjustments for age and sex, but not case mix, of rostered patients. We evaluated the extent to which persons with mental illness were included in physicians’ total practices (as rostered and non-rostered patients) and were included on physicians’ rosters across types of medical homes in Ontario.

Methods

Using population-based administrative data, we considered 3 groups of patients: those with psychotic or bipolar diagnoses, those with other mental health diagnoses, and those with no mental health diagnoses. We modelled the prevalence of mental health diagnoses and the proportion of patients with such diagnoses who were rostered across the 3 medical home model types, controlling for demographic characteristics and case mix.

Results

Compared with enhanced fee-for-service practices, and relative to patients without mental illness, the proportions of patients with psychosis or bipolar disorders were not different in blended capitation and team-based blended capitation practices (rate ratio [RR] 0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.82–1.01; RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.96–1.17, respectively). However, there were fewer patients with other mental illnesses (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.90–0.99; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.85–0.94, respectively). Compared with expected proportions, practices based on both capitation models were significantly less likely than enhanced fee-for-service practices to roster patients with psychosis or bipolar disorders (for blended capitation, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.90–0.93; for team-based capitation, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.93) and also patients with other mental illnesses (for blended capitation, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.92–0.95; for team-based capitation, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.92–0.94).

Interpretation

Persons with mental illness were under-represented in the rosters of Ontario’s capitation-based medical homes. These findings suggest a need to direct attention to the incentive structure for including patients with mental illness.

The concept of the “patient-centred medical home” has been promoted by primary care organizations as a model for health service delivery that has the potential to improve the accessibility, affordability, and quality of health care.1,2 A “medical home” for patients includes a physician-led multidisciplinary clinic that provides comprehensive primary care, expanded hours, integrated evidence-based quality measurement, and modern health information technology. In Ontario, Canada, several types of medical homes have been developed since 2002.2 By August 2008, almost half of the province’s 13 million residents and more than half of the province’s 11 000 primary care physicians had voluntarily joined medical home models that offered patient rostering, after-hours coverage, incentives for preventive health care, and payments for chronic disease management. Approximately 4 million of these patients had been transitioned from fee-for-service to blended capitation practices. Almost half of the capitation practices were team-based, many of them incorporating mental health workers in their multidisciplinary clinician teams.

In North America, about one-third of primary care patients meet the criteria for a psychiatric disorder within any 12-month period,3 but fewer than half of those with mental health disorders actually receive treatment.4-7 Primary care physicians are the most commonly consulted providers of mental health services8 and often are the only providers contacted.6,9 People with mental illness, however, experience more difficulty accessing primary care than the general population.10,11 As such, increasing access to primary health services for people with mental illness is a priority for policy-makers in Ontario12 and elsewhere in Canada.13

While a small minority of physicians work on salary in Community Health Centres, which have existed for decades in Ontario,14 primary care reform in the province resulted in the widespeard adoption of 3 new types of medical homes, distinguished primarily by mode of physician remuneration: enhanced fee-for-service, blended capitation, and team-based blended capitation.15 In enhanced fee-for-service practices, claims are paid in full. In contrast, reimbursement in the blended capitation models is based on the age and sex distribution of rostered patients, with no adjustment for case mix, and fee-for-service claims are paid at 10% of their full value.16 The major distinction between the 2 blended capitation models is that team-based practices have nonphysician providers, often including mental health workers.17,18 Patient rostering is performed in all 3 models. Rostering is voluntary for patients and allows them access to additional services, such as physician-provided treatment or advice during evening and weekend hours and a 24-hour nurse-staffed telephone service. Primary care physicians are eligible to receive financial incentives for providing specific services to rostered patients, including preventive health care and chronic disease management. In every model, physicians are remunerated on a fee-for-service basis when they provide care to non-rostered patients; however, there is a cap on such income in the blended capitation models.16,19

Physicians in all 3 types of medical homes can receive financial incentives for rostering patients with severe mental illness. Primary care practitioners are offered $1000 per year for rostering 5 patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and an additional $1000 for rostering another 5 such patients (i.e., maximum incentive $2000).20 Despite these incentives, we hypothesized that physicians working under the capitation models would be less likely to roster patients with mental illness because of the greater expected needs for care. The tendency for capitation physicians to selectively roster healthier patients because of the financial risks associated with treating patients with higher morbidity has been termed “cream-skimming” or “cherry-picking.”21,22

The inclusion of patients with mental illness in Ontario medical homes has not been explored. Accordingly, we addressed 2 research questions: First, is there evidence that the prevalence of mental illness varies by model type? Second, is there evidence that physicians working under capitation models are less likely to roster patients with mental health needs relative to those working in enhanced fee-for-service practices?

Methods

Study design

For this cross-sectional study, we analyzed administrative claims data for rostered and non-rostered patients with and without mental illness in different medical home models. We accessed non-nominal data with encrypted unique identifiers through a comprehensive research agreement with the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Setting

This study was conducted at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto, Ontario, and was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, also in Toronto.

Participants

The study population comprised Ontario residents with valid Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP) coverage who were 18 years or older as of August 31, 2008. This insurance program covers all medically necessary physician and hospital services, without copayments or deductibles, and is available to all permanent residents. Patients were excluded if they had not had at least one visit with a primary care practitioner between September 1, 2006, and August 31, 2008, or if the physician deemed to be the patient’s most responsible physician was not practising in a medical home model. We identified primary care physicians belonging to 1 of the 3 medical home models of interest and patients rostered with those physicians using provincial Client Agency Program Enrolment tables as of August 31, 2008. To calculate the prevalence of mental illness in physicians’ total practices and to examine whether physicians preferred to be remunerated through fee for service or rostering for this complex population, we also created a “virtual roster” of non-rostered patients for each physician. Each non-rostered patient was assigned a most-responsible physician according to the maximum dollar value of 18 comprehensive primary care billing codes. For each physician belonging to a registered medical home who was identified as a most-responsible physician, the linked non-rostered patients constituted that physician’s virtual roster.23

Variables and data sources

Ontario medical homes that were registered as of August 31, 2008, were categorized into 1 of 3 types on the basis of their designation by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care: enhanced fee-for-service practices included Family Health Groups, blended capitation practices included Family Health Networks and Family Health Organizations, and team-based blended capitation practices included Family Health Teams.

The study population was divided into 3 mental health categories according to OHIP ambulatory diagnostic codes applied between September 1, 2006, and August 31, 2008 (see Appendix A). Patients were assigned to the following groups: those with one or more billings for psychotic or bipolar diagnoses, those with one or more billings for other mental health diagnoses (e.g., anxiety or depression), and those with no mental health diagnoses. Persons were assigned to mental health groups in a hierarchical fashion, such that a psychotic or bipolar diagnosis was assigned to any individual with a related billing, even if the person also had billings for other mental health diagnoses. A previous study showed that ambulatory claims from primary care physicians had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 97% for identifying mental health visits to primary care physicians.24 There is evidence that this method is also highly specific for psychotic or bipolar diagnoses (99.4%), although less sensitive (55.3%).25

Patient characteristics were obtained from Ontario’s Registered Persons Database, which holds information on age, sex, and place of residence for all persons covered by OHIP. We also used the provincial Registered Persons Database to identify those with first-time registration after April 1, 1998, as probable immigrants to Canada.26 Although that group includes some interprovincial migrants, more than 80% are expected to be international migrants. Statistics Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File was used to link patients’ postal codes to census data. Census subdivisions for 2006, in combination with the Ontario Medical Association’s Rurality Index for Ontario,27 were used to assign a rurality score to each patient’s residence address. Rurality scores (which could range from 0 to 100) were divided into 3 categories: major urban areas (score 0 to 9), non-major urban areas (10 to 44), and rural areas (45 or higher). Household income quintile was assigned by linking postal codes with 2006 Census Dissemination Areas after accounting for average household size and community of residence. Comorbidity was measured with the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups System.28,29 Within this system, counts of Aggregated Diagnosis Groups indicate level of comorbidity; these counts range from 0 (no diagnosis) to 24 distinct diagnosis groups. The ACG system is one of the best performers for predicting health service utilization in primary care settings.30 Finally, we used the validated Ontario Diabetes Database to identify study patients who had diabetes mellitus. The algorithm used to populate the database has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of over 97% in identifying patients with confirmed diabetes.31

Physician characteristics, specifically age, sex, years since medical graduation, and country of graduation, were obtained from the Corporate Provider Database and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences’ Physician Database. The number of rostered patients for each physician and the number of months a physician had been in the model were derived from the Client Agency Program Enrolment database. Rurality of physician practice was designated by the Rurality Index for Ontario score of the practice location, as described above.

Study size

Because our study was population-based and was based on administrative data from the province’s single-payer health system, we did not use a sampling technique. Rather, our study considered 7 334 408 people, the entire group of eligible residents of Ontario.

Statistical analysis

To determine if there was evidence of physicians self-selecting into specific model types on the basis of their practice make-up, we first conducted a bivariate analysis comparing the average prevalence of mental health diagnoses across model types. We then used Poisson regression to adjust for potentially confounding variables. Poisson regression has been demonstrated to produce useful and accurate estimates when the outcome data are prevalence rates.32,33 We modelled the number of people with a mental health diagnosis, offset by the log of the total number of people in the study population. We conducted all analyses at the level of the physician and used generalized estimating equations to account for the clustering of patients within physicians’ practices and of physicians within practice groups. Covariates were mean patient age, proportion of patients that were female, rurality of office location, proportion of patients in the lowest income quintile, median patient comorbidity score, physician years since medical graduation, physician months in group, foreign graduation, and mean number of rostered patients. Physicians with missing data were excluded from the adjusted analyses.

To determine if there was preferential rostering of patients without mental health diagnoses and if so, whether it differed by model type, we conducted a bivariate analysis of the proportion of rostered patients (rostered patients/[rostered patients + patients on virtual roster]) across the mental health categories for each of the 3 model types. We then used Poisson regression, as described above, to adjust these analyses for potential confounding. In this case, we modelled the observed likelihood of rostering for patients in each mental health category by model type. We used the expected proportion rostered (i.e., the overall proportion rostered for each mental health category) to offset the observed proportion. Proportions were calculated at the level of the physician and then compared across model types. Physicians with missing data were excluded from the adjusted analysis. Rate ratios (RRs) were developed to compare the likelihood of inclusion of patients with mental illness and the likelihood of rostering these patients in capitation-based models relative to enhanced fee-for-service models. Separate RR values were calculated for patients with 2 broad categories of mental illness: (1) psychotic or biopolar disorders and (2) other types of disorders.

To check the validity of our models’ assumptions, we examined residual-by-predicted plots for continuous predictor variables. Assumptions of independence, normality, equality of variance, and linearity did not appear to be violated.

Results

Participants

A total of 10 006 856 adult Ontarians were registered with OHIP on August 31, 2008. We excluded 2 672 448 patients who had not had contact with any of the 6033 primary care practitioners belonging to a medical home model in the 2-year study period; this left 7 334 408 patients who were linked to a primary care practitioner. Of these, 6 259 718 patients (85.3%) were rostered in their respective physicians’ medical homes and 1 074 690 (14.7%) were not rostered and were therefore placed on our “virtual roster”. The majority of patients (65.9%) were affiliated with physicians in enhanced fee-for-service practices, 19.4% were affiliated with physicians in blended capitation practices, and 14.7% were affiliated with physicians in team-based blended capitation practices. We determined unadjusted rostering rates of 82.4%, 91.7%, and 90.5% for enhanced fee-for-service, blended capitation, and team-based capitation models, respectively. The unadjusted rostering rate for all models combined was 85.3%.

Descriptive data

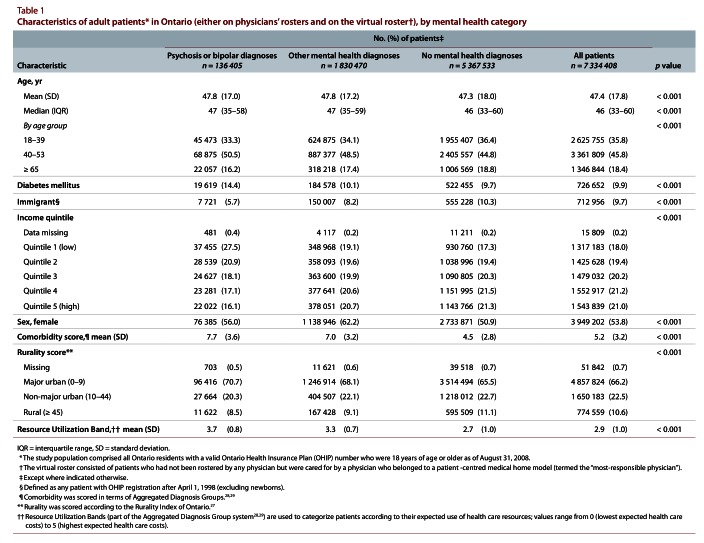

Patients with mental health diagnoses were more likely to live in urban areas, to have higher comorbidity scores, and to be in a lower income quintile than patients with no mental health diagnosis (Table 1). Differences were most marked for individuals with psychotic or bipolar diagnoses. Individuals with mental health diagnoses were more likely to be female.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in Ontario, by mental health category

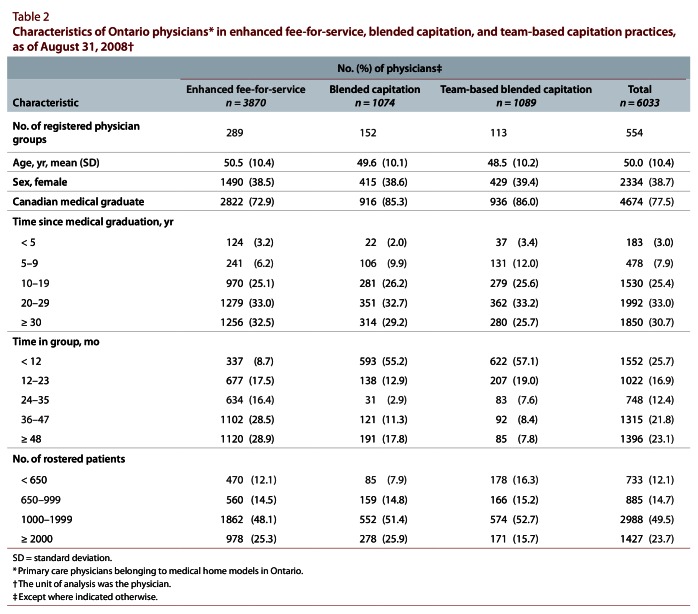

Physicians in the 2 blended capitation models were more likely to be Canadian medical graduates and more likely to have joined their groups within the previous 12 months (Table 2). Physicians in team-based blended capitation models were less likely than physicians in the other 2 models to have practices with at least 2000 rostered patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Ontario physicians in enhanced fee-for-service, blended capitation, and team-based capitation practices, as of August 31, 2008

Main results

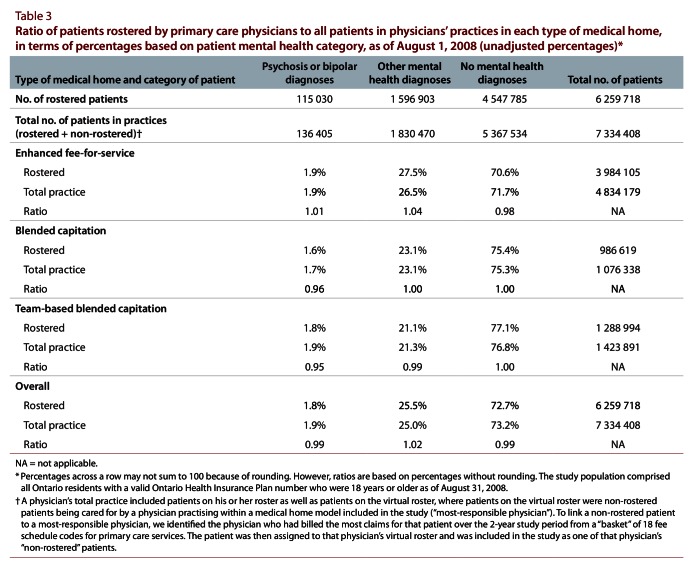

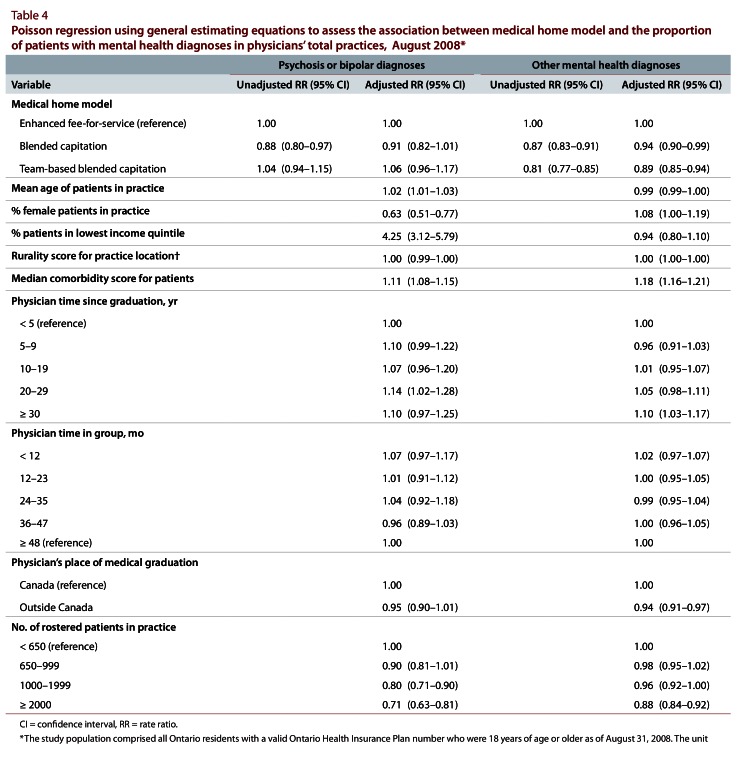

In terms of the prevalence of mental health diagnoses in physicians’ total practices across types of medical homes, the unadjusted analysis showed small differences in the proportions of patients with psychotic or bipolar diagnoses (Table 3). Enhanced fee-for-service practices had the highest proportions of persons with other mental health diagnoses. The 2 blended capitation models had the highest proportions of patients with no mental illness (Table 3). After adjustment, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of psychotic and bipolar diagnoses among the 3 model types (Table 4). However, physicians in both blended capitation model types had significantly lower proportions of patients with other mental health disorders relative to physicians in enhanced fee-for-service models (for blended capitation, RR 0.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–0.99; for team-based blended capitation, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.85–0.94) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Ratio of patients rostered by primary care physicians to all patients in physicians’ practices in each type of medical home, in terms of percentages based on patient mental health category, as of August 1, 2008 (unadjusted percentages)

Table 4.

Poisson regression using general estimating equations to assess the association between medical home model and the proportion of patients with mental health diagnoses in physicians’ total practices, August 2008

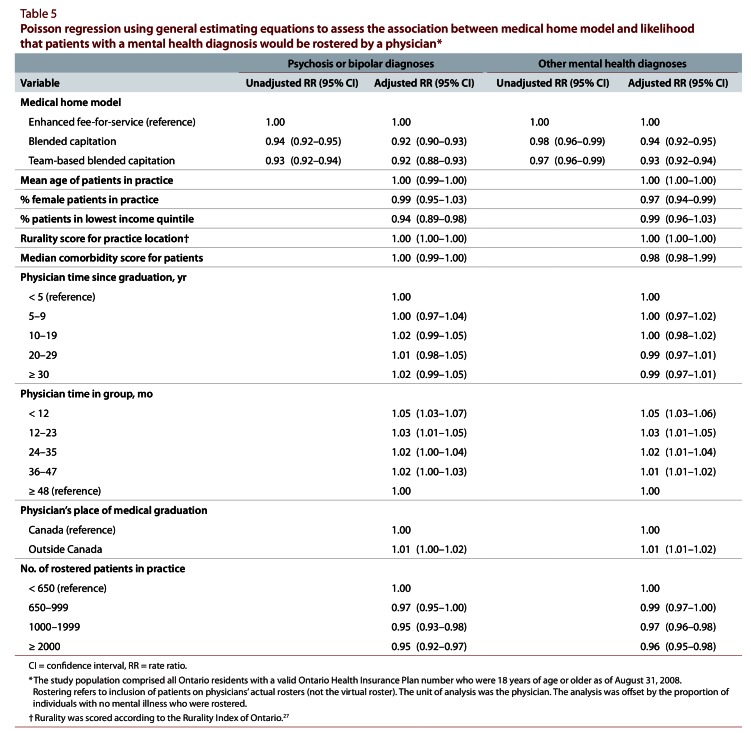

We also examined the likelihood of a physician rostering a patient with a mental health diagnosis, relative to the likelihood of rostering a patient with no mental health diagnosis, across medical home type. If rostering were equitable for patients with mental health diagnoses, then the ratio of the percentage of a given diagnostic group that a physician rosters to the percentage of that diagnostic group in the physician’s total practice should equal 1.0. However, in our bivariate analyses, physicians in enhanced fee-for-service practices were more likely to roster patients with mental health diagnoses (since the ratio of the percentage of each mental health diagnostic group rostered to the percentage of the respective diagnostic group in total practice was 1.01 for psychosis and bipolar diagnoses and 1.04 for other mental health diagnoses), relative to patients with no mental health diagnoses (ratio of being rostered relative to not being rostered 0.98). This trend was not observed for blended capitation or team-based blended capitation models (Table 3). After adjustment, significant differences remained in the likelihood that physicians in different medical home models rostered patients with mental illness relative to patients with no mental illness. Physicians in blended capitation and team-based blended capitation practices were significantly less likely than physicians in enhanced fee-for-service practices to roster patients with psychotic or bipolar diagnoses (for blended capitation, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.90–0.93; for team-based blended capitation, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.93) and patients with other mental health diagnoses (for blended capitation RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.92–0.95; for team-based blended capitation, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.92–0.94) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Poisson regression using general estimating equations to assess the association between medical home model and likelihood that patients with a mental health diagnosis would be rostered by a physician

Interpretation

The proportions of patients with psychotic or bipolar disorders were similar across physician payment models. However, compared with enhanced fee-for-service practices, capitation practices had lower proportions of patients with other mental illness and higher proportions of patients with no mental illness. After the prevalence of mental illness in physicians’ total practices and the overall rate of rostering were accounted for, physicians in capitation practices were less likely to roster patients with psychotic or bipolar diagnoses and patients with other mental illness diagnoses, compared with physicians in enhanced fee-for-service practices. To our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study to demonstrate selective rostering for patients with mental illness, after accounting for differences in the proportion of mental illness in physicians’ total practices.

Physician remuneration influences physician behaviour.22,34,35 Physicians in capitation models may select low-needs patients as a way to maximize their income relative to the volume of service provision required (“cream-skimming”).22,36 Patients with mental illness represent a high-needs population.9,37,38 In Ontario, where capitation compensation in patient-centred medical homes is determined by the age and sex of rostered patients, not by their health status, physicians could suffer negative financial repercussions for rostering mentally ill patients. Even with the additional financial incentives provided by the government for rostering patients with severe mental illness (the maximum possible amount being $2000 per year), it may still be financially advantageous for Ontario physicians to selectively roster healthier patients.22,39 Policy options to address this issue include higher incentive payments, different incentives for enrolment and care of these patients, and inclusion of a case-mix adjustment in calculating physician remuneration.

There is limited international research on enrolment of patients with mental illness in capitation models relative to fee-for-service models. Managed care plans in the United States are similar to Canadian capitation-based models,40 but findings from US studies are mixed. McFarland et al. found no evidence that persons with chronic mental illness were excluded from health maintenance organizations.41 However, Gresenz and Sturm reported that patients with severe mental disorders were significantly more likely to be derostered than patients with less severe mental health problems.42 This inconsistency highlights the need for additional research on this topic.

Policies are in place to limit the potential for Ontario physicians to discriminate against groups of patients when they are building their clinical practices. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario prohibits decision-making about the provision of medical services on the basis of an individual’s personal characteristics, including level of disability. However, a physician could provide services to all patients while rostering only his or her healthy patients and still be in compliance with the College policy.43 On the other hand, the contract between physicians and the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in some capitation models requires them to offer rostering to every patient. In those models, physicians may still frame the benefits of enrolment differently to different patient groups, which could, subtly or otherwise, facilitate “cream-skimming.” An additional policy approach may be to implement a surveillance mechanism to identify physicians who do not appear to be adhering to the non-discrimination provision of the College policy or to their contract with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

It is unclear how exclusion from enrolment in medical home models affects access to care and quality of care for patients with mental illness in Canada. It is possible that capitation physicians are able to provide intensive care for higher-needs patients without suffering a financial insult by keeping mentally ill patients off their rosters. This approach ensures that the physicians receive fee-for-service remuneration for those patients. When patients are not rostered however, physicians do not receive incentive payments for preventive health care or chronic disease management, 2 areas in which people with mental illness are already disadvantaged.44-47 Non-rostered patients are also less likely to be included in quality improvement initiatives that generate reports or reminders and are not eligible for incentives for after-hours care. There is consensus about a need to measure the long-term effects of membership in capitation (or managed care) models on use of mental health services.21,48

Limitations

We employed an administrative measure that has been validated in a primary care setting and appears to accurately identify health services provided for mental health reasons.24 The reported sensitivity for identifying psychotic disorders is relatively low (55.3%).25 However, validation of the diagnostic codes was undertaken before implementation of financial incentives for using these codes for psychotic disorders. Consequently the actual sensitivity in our setting is likely higher. Our confidence in the accuracy of our measure is further bolstered by the fact that the overall prevalence of psychotic disorders that we observed (1.9%) is what would be expected on the basis of studies of the prevalence of psychotic disorders in Canada using other data sources: schizophrenia (1%)49 and bipolar disorder (0.4% to 1%).50 This concordance implies that our database is not missing a significant proportion of individuals with serious mental illness.

This study had potential for misclassification bias. Capitation physicians were paid 10% of fee-for-service fees for each claim submitted during the study period; consequently, they had less incentive than enhanced fee-for-service physicians to fully document the services provided. Because we used billing data to define our mental health groups, this situation may have resulted in an underestimation of the proportion of rostered patients with mental disorders in capitation practices.

Our study did not include data from a fourth type of medical home in Ontario, the Community Health Centre (CHC). Glazier et al. recently found that the patients of CHCs are more likely than those in other practice models to have serious mental illness (5.6% v. 1.4%–1.7%).51 CHC physicians are paid by salary rather than by capitation, and they are often mandated to serve marginalized populations. Although CHCs serve more individuals with serious mental illness than other practice models, this group constitutes a relatively small proportion of this patient population in Ontario. Glazier et al.51 reported that CHCs in Ontario have a total of 110 000 clients (0.9% of Ontarian patients); consequently, they serve only 3.4% of Ontario’s 178 400 patients with serious mental illness. It is thus unlikely that the exclusion of these data from the current study significantly biased our results.

Conclusions

We conclude that people with mental illness are under-represented in Ontario’s capitation-based medical homes. The Ontario experience can inform primary care reform efforts in the United States and other countries with similar resident populations.52 Determining appropriate payment structures and providing appropriate incentives for mental health care in capitation-based medical homes may be challenging. Our analysis highlights the importance of monitoring health care use and outcomes for patients with mental illness in medical home models as a way to inform payment and incentive structures that will optimize access to care and improve health outcomes.

Biographies

Leah S. Steele, BA, MD, PhD, CCFP, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; a Scientist in the Department of Family and Community Medicine and the Keenan Research Institute of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital; and an Adjunct Scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Ontario.

Anna Durbin, BA(Hons), MPH, is a PhD candidate in the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Lyn M. Sibley, BSc, MHA, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Health System Performance Research Network and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Richard H. Glazier, MD, MPH, is a Senior Scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; a Scientist at the Centre for Research on Inner City Health in the Keenan Research Centre of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital; and a Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario.

Appendices

Appendix A.

Ontario Health Insurance Program diagnostic codes (ICD-9) for psychotic or bipolar disorders and other mental health diagnoses

Footnotes

Competing interests: During the conduct of this study, Leah Steele received salary support in part through a Career Scientist Award from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. No other competing interests declared.

Funding source: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Contributors: The project was originally conceived and designed by Richard Glazier and Leah Steele. Lyn Sibley conducted the analyses and contributed to the methodologic approach. Anna Durbin contributed substantially to the data interpretation and drafted the original manuscript in collaboration with Leah Steele. All authors participated in successive revisions and improvements, and all approved the final version for publication.

References

- 1.Rosenthal Thomas C. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):427–440. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=18772297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glazier Richard H, Redelmeier Donald A. Building the patient-centered medical home in Ontario. JAMA. 2010 Jun 2;303(21):2186–2187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cwikel Julie, Zilber Nelly, Feinson Marjorie, Lerner Yaacov. Prevalence and risk factors of threshold and sub-threshold psychiatric disorders in primary care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007 Nov 16;43(3):184–191. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Philip S, Lane Michael, Olfson Mark, Pincus Harold A, Wells Kenneth B, Kessler Ronald C. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=15939840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinshaw S P, Cicchetti D. Stigma and mental disorder: conceptions of illness, public attitudes, personal disclosure, and social policy. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(4):555–598. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004028. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=11202034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin E, Goering P, Offord D R, Campbell D, Boyle M H. The use of mental health services in Ontario: epidemiologic findings. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41(9):572–577. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasiliadis Helen-Maria, Lesage Alain, Adair Carol, Wang Philip S, Kessler Ronald C. Do Canada and the United States differ in prevalence of depression and utilization of services? Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):63–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.1.63-a. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=17215414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesage A D, Goering P, Lin E. Family physicians and the mental health system. Report from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:251–256. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/9040912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan M, Stradins L, Morrison S. Physical health of people with severe mental illness. BMJ. 2001 Feb 24;322(7284):443–444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.443. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/11222406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bebbington P E, Meltzer H, Brugha T S, Farrell M, Jenkins R, Ceresa C, Lewis G. Unequal access and unmet need: neurotic disorders and the use of primary care services. Psychol Med. 2000;30(6):1359–1367. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002950. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=11097076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford Daniel W, Kim Mimi M, Braxton Loretta E, Marx Christine E, Butterfield Marian, Elbogen Eric B. Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(8):847–852. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.847. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=18678680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Select Committee on Mental Health and Addictions. Final report. Navigating the journey to wellness: the comprehensive mental health and addictions action plan for Ontarians. 2nd session, 39th parliament, 59 Elizabeth II. Toronto (ON): Legislative Assembly of Ontario; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby MJL, (chair), Keon WJ., (deputy chair) Out of the shadows at last: transforming mental health, mental illness and addiction services in Canada. 39th parliament, 1st session. Ottawa (ON): Senate of Canada, Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ontario’s Community Health Centres. Toronto (ON): Association of Ontario Health Centres; [accessed 2012 Aug 1]. http://www.ontariochc.ca/index.php?ci_id=2341&la_id=1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kralj B, Kantarevic J. Primary care in Ontario: reforms, investments and achievements. Ont Med Rev. 2012 Feb;:18–24. https://www.oma.org/Resources/Documents/PrimaryCareFeature.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glazier R H, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Sibley L M. Capitation and enhanced fee-for-service models for primary care reform: a population-based evaluation. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):72–81. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081316. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/19468106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guide to interdisciplinary provider compensation. Version 3.2. Toronto (ON): Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2010. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/fht/docs/fht_inter_provider.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchison Brian. A long time coming: primary healthcare renewal in Canada. Healthc Pap. 2008;8(2):10–24. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2008.19704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Family Health Teams. Advancing primary care. Guide to patient enrolment. Toronto (ON): Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2005. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/fht/docs/fht_enrolment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billing and payment information for Family Health Network (FHN) signatory physicians [fact sheet] Toronto (ON): Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Primary Health Care Team; 2006. http://www.anl.com/MOHGUIDE/09%20Billing%20and%20Payment%20Information%20for%20Family%20Health%20Network%20(FHN)%20Signatory%20Physicians%20-%20October%202006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leff H S, Wieman Dow A, McFarland Bentson H, Morrissey Joseph P, Rothbard Aileen, Shern David L, Wylie A M, Boothroyd Roger A, Stroup T S, Allen I E. Assessment of Medicaid managed behavioral health care for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(10):1245–1253. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1245. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=16215190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg R J. Financial incentives influencing the integration of mental health care and primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1071–1075. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1071. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=10445657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal M. Primary care reform: a case study of Ontario [dissertation] Toronto (ON): University of Toronto; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele Leah S, Glazier Richard H, Lin Elizabeth, Evans Michael. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care. 2004;42(10):960–965. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele L S. Ambulatory mental health service use in an inner city setting: measurement, patterns and trends [dissertation] Toronto (ON): University of Toronto; 2003. Measuring ambulatory mental health services using administrative data; pp. 25–77. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray Joel G, Vermeulen Marian J, Schull Michael J, Singh Gita, Shah Rajiv, Redelmeier Donald A. Results of the Recent Immigrant Pregnancy and Perinatal Long-term Evaluation Study (RIPPLES) CMAJ. 2007 May 8;176(10):1419–1426. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061680. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/17485694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kralj B. Measuring ‘rurality’ for purposes of health care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Rev. 2000;67(9):33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johns Hopkins ACG case mix system: version 6.0 release notes. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johns Hopkins adjusted clinical groups (ACG) system . Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huntley Alyson L, Johnson Rachel, Purdy Sarah, Valderas Jose M, Salisbury Chris. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):134–141. doi: 10.1370/afm.1363. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=22412005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hux Janet E, Ivis Frank, Flintoft Virginia, Bica Adina. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512–516. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=11874939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barros Aluísio J D, Hirakata Vânia N. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003 Oct 20;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/3/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frome E L, Checkoway H. Epidemiologic programs for computers and calculators. Use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(2):309–323. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114001. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=3839345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I S, Sutton M, Leese B, Giuffrida A, Sergison M, Pedersen L. Impact of payment method on behaviour of primary care physicians: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2001;6(1):44–55. doi: 10.1258/1355819011927198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauly M V, Kissick W L, Roper L E, editors. Lessons from the first twenty years of Medicare: research implications for public and private sector policy. Philadelphia (PA): University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold M. Financial incentives: current realities and challenges for physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14 Suppl 1 doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00260.x. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/9933489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAlpine D D, Mechanic D. Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: the roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(1 Pt 2):277–292. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/10778815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samele Chiara, Patel Maxine, Boydell Jane, Leese Morven, Wessely Simon, Murray Robin. Physical illness and lifestyle risk factors in people with their first presentation of psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006 Nov 23;42(2):117–124. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0135-2. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=17187169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothbard Aileen B, Kuno Eri, Hadley Trevor R, Dogin Judith. Psychiatric service utilization and cost for persons with schizophrenia in a Medicaid managed care program. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02287334. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=14722476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sekhri N K. Managed care: the US experience. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(6):830–844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McFarland B H, Johnson R E, Hornbrook M C. Enrollment duration, service use, and costs of care for severely mentally ill members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(10):938–944. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100086011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gresenz C R, Sturm R. Who leaves managed behavioral health care? J Behav Health Serv Res. 1999;26(4):390–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02287300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Physicians and the Ontario human rights code. Policy 5-08. Toronto (ON): College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario; 2008. http://www.cpso.on.ca/policies/policies/default.aspx?ID=2102. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Druss Benjamin G, Rosenheck Robert A, Desai Mayur M, Perlin Jonathan B. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40(2):129–136. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00007. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=11802085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carney Caroline P, Jones Laura E. The influence of type and severity of mental illness on receipt of screening mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1097–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00565.x. http://pubmedcentralcanada.ca/pmcc/articles/pmid/16970559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirraglia Paul A, Sanyal Pallabi, Singer Daniel E, Ferris Timothy G. Depressive symptom burden as a barrier to screening for breast and cervical cancers. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13(6):731–738. doi: 10.1089/1540999041783190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vigod Simone N, Kurdyak Paul A, Stewart Donna E, Gnam William H, Goering Paula N. Depressive symptoms as a determinant of breast and cervical cancer screening in women: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011 Feb 11;14(2):159–168. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0210-x. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=21311925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou A F, Wallace N, Bloom J R, Hu T W. Variation in outpatient mental health service utilization under capitation. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8(1):3–14. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=15870481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Häfner H, an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1997;42(2):139–151. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulloch A G, Currie S, Guyn L, Williams J V, Lavorato D H, Patten S B. Estimates of the treated prevalence of bipolar disorders by mental health services in the general population: comparison of results from administrative and health survey data. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2011;31(3):129–134. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cdic-mcbc/31-3/ar-07-eng.php. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glazier R H, Zagorski B M, Rayner J. Comparison of primary care models in Ontario by demographics, case mix and emergency department use, 2008/09 to 2009/10. Toronto (ON): Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012. [accessed 2012 Jan 17]. http://www.ices.on.ca/file/ICES_Primary%20Care%20Models%20English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosser Walter W, Colwill Jack M, Kasperski Jan, Wilson Lynn. Patient-centered medical homes in Ontario. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jan 6;362(3) doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911519. http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMp0911519?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]