Abstract

This work focuses on the structural changes of barium chloride (BaCl2) nanoparticles in fluorochlorozirconate-based glass ceramics when doped with two different luminescent activators, in this case rare-earth (RE) ions, and thermally processed using a differential scanning calorimeter. In a first step, only europium in its divalent and trivalent oxidation states, Eu2+ and Eu3+, is investigated, which shows no significant influence on the crystallization of hexagonal phase BaCl2. However, higher amounts of Eu2+ increase the activation energy of the phase transition to an orthorhombic crystal structure. In a second step, nucleation and nanocrystal growth are influenced by changing the structural environment of the glasses by co-doping with Eu2+ and trivalent Gd3+, Nd3+, Yb3+, or Tb3+, due to the different atomic radii and electro-negativity of the co-dopants.

Keywords: crystallization, glass ceramics, rare-earth doping, nanocrystals

1. Introduction

Recent studies have shown that fluorochlorozirconate (FCZ)-based glasses and glass ceramics doped with rare-earth (RE) ions such as Eu2+ are good candidates for image plates in medical diagnostics and up- or down-conversion layers for solar cells providing broad and strong blue luminescence upon ultraviolet or x-ray excitation [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

The BaCl2 is crystallized by thermal treatment of the “aspoured” glass leading to nucleation and growth of nanocrystals in the glass matrix, creating a glass ceramic. These few hundred nanometer-sized crystals, in which a part of the luminescent activator ions are incorporated, provide lower phonon frequencies, making non-radiative relaxation processes less probable; this enables an enhanced luminescence yield. It is therefore essential to be able to precisely control the nanocrystallite nucleation and growth. Previous work has shown that the BaCl2 crystallization activation energy is affected by RE doping [6]. More general work on crystallization in zirconium fluoride glasses can be found in [7, 8].

At this moment, several routes are being explored to reduce costs of Eu2+-doped glasses and to achieve a higher total luminescence output [9, 10]. It was shown that during glass melting cheaper Eu3+ is partially reduced to the more expensive Eu2+, meaning that multivalent doping of Eu2+ and Eu3+ in the starting materials can reduce costs.

In an attempt to enhance light output, the Eu2+ glasses were additionally doped with a further RE, namely Gd, Nd, Yb, or Tb, to study possible energy transfer between the RE dopants and potential effects on the optical and structural properties. This work focuses on how the varying amounts of divalent and trivalent Eu and the different RE dopants affect the BaCl2 crystallization investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). For medical and photovoltaic applications it is essential to perform DSC measurements on all glass ceramics to be able to optimize the annealing conditions as well as the respective luminescence yield.

2. Materials and methods

The investigated fluorochlorozirconate (FCZ) glasses are based on a modified ZBLAN composition [11], which nominally consists of 51ZrF4-20BaCl2-20NaF-3.5LaF3-3AlF3-0.5InF3-xEuCl2-(2-x)EuCl3 (x = 0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0) (values in mol%) for the multivalent Eu series and 51ZrF4-20BaCl2-20NaF-3.5LaF3-3AlF3-0.5InF3-1EuCl2-1RECl3 (RE = Gd3+, Nd3+, Tb3+, Yb3+) for the RE co-doping series (values in mol%).

Glass preparation was done under an argon atmosphere inside a glove box. A two-step melting process was used, where the first step involved mixing and melting of all fluorides at 800 °C for 60 minutes. After being cooled to room temperature chlorides were added to the melt and the whole composition was remelted for 60 minutes at 745 °C. The last step involved pouring into a 200 °C hot brass mold, where it stayed for 60 minutes before being cooled to room temperature at 50 °C per hour.

The DSC measurements were performed with a DSC 204 F1 Phoenix instrument (Netzsch). The sample was cut into small pieces of about 20 to 40 mg and then placed in an aluminum crucible. An empty crucible was used as a reference. The temperature was increased with heating rates of 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 K/min while the differential temperature between the crucibles was measured.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Multivalent Eu-doping

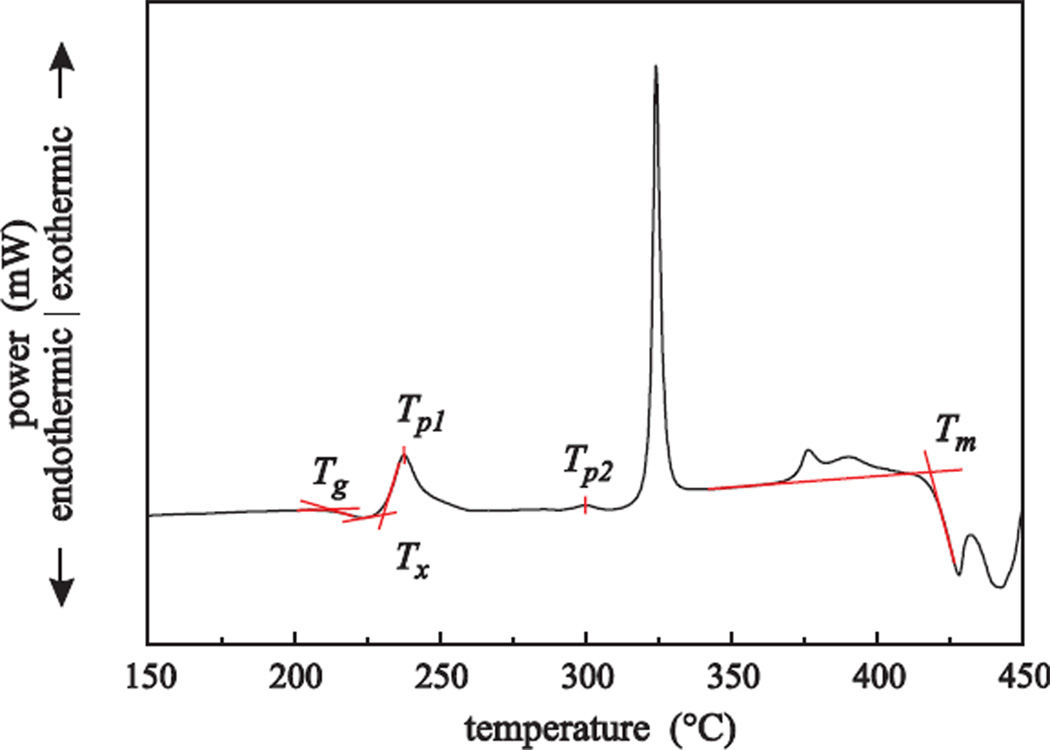

The oxidation state’s influence on the crystallization is shown by non-isothermal DSC measurements. The important points of interest are marked in Figure 1 for an FCZ glass with an Eu2+ fraction of 60%, measured with a heating rate of 10 K/min. Tg is the glass transition temperature, i.e., the point where glass viscosity and specific heat capacity drop significantly. The crystallization onset, Tx, and the peak temperature of the first crystallization, Tp1, are attributed to the crystallization of hexagonal BaCl2, while Tp2 is attributed to the phase transition from hexagonal to orthorhombic BaCl2.

Figure 1.

Plot of the DSC data for the FCZ glass with a Eu2+ fraction of 60%. The heating rate was 10 K/min.

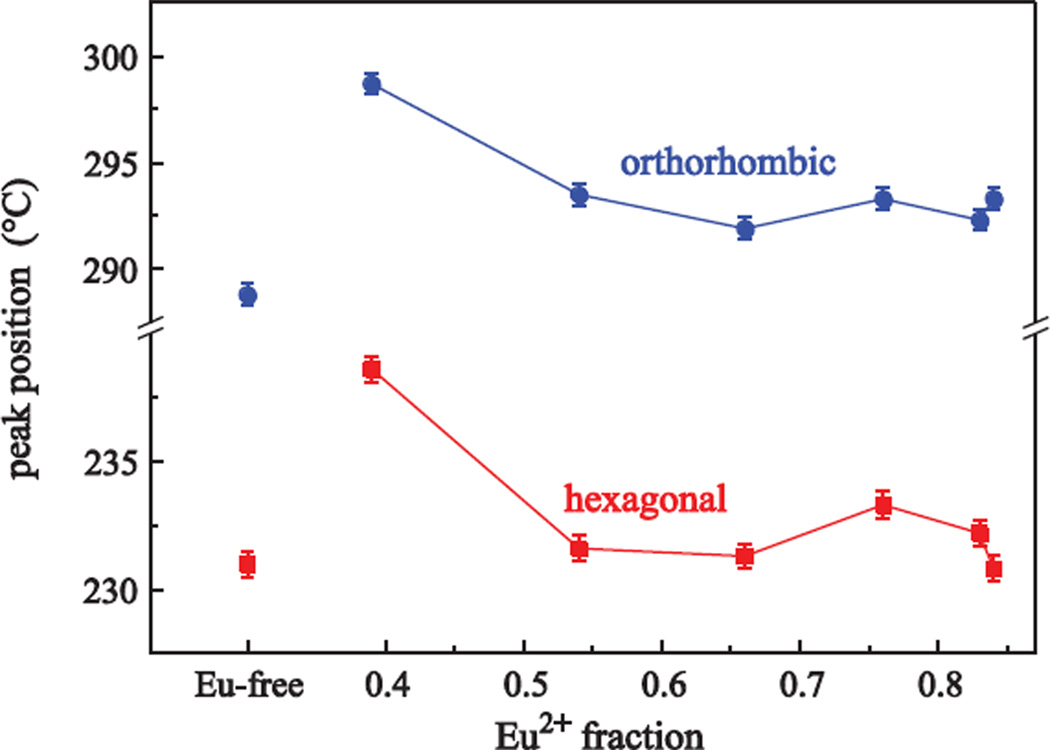

In previous work, x-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy (XANES) was used to evaluate Eu2+-to-Eu3+ ratios, accurately. Nominal and experimentally determined values are summarized in Table 1. The listed experimentally determined value is the average of all ratios of the as-made and the differently annealed samples having the same composition. A detailed description of the analysis and the experimental details can be found in [10]. Figure 2 shows the peak temperature of both hexagonal and orthorhombic peak maxima as a function of the different Eu2+-to-Eu3+ doping fractions; the heating rate was 5 K/min. A significant shift to lower temperatures is observed for both peaks when increasing the Eu2+ fraction from 0% to 20%. This trend confirms the behavior of the phase transition temperature obtained from corresponding x-ray diffraction (XRD) data of the heat treated samples [10]: For pure EuCl3 doping, higher annealing temperatures are required to convert the hexagonal particles into particles with orthorhombic crystal structure. The hexagonal phase results from 20 minute heat treatments between 250 to 270 °C; at 280 °C a phase mixture of hexagonal and orthorhombic phase is found, while the fully crystallized orthorhombic phase is not observed before 290 °C. Crystallization peak positions for a Eu-free ZBLAN glass are shown for comparison. Averaging the peak temperatures of the Eu-doped samples shows that Eu doping leads to a higher temperature shift for the transformation to the orthorhombic phase (Tp2 = 289 °C for the Eu-free sample to T̄p2 = 294 °C for the Eu-doped samples) than for the hexagonal phase crystallization (Tp1 = 231 °C for the Eu-free sample to T̄p2 = 233 °C for the Eu-doped samples). This behavior is described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Overview of nominal and experimentally determined Eu2+ fractions for the multivalent Eu-doping series. A nominal Eu2+ fraction of 100% corresponds to a Eu2+ doping level of x = 2.0 mol%. The experimental analysis was done by x-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) [10]. The respective Eu3+ fraction is given by 1 − Eu2+.

| nominal Eu2+ fraction (%) |

experimental Eu2+ fraction (averaged) (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 39 ± 4 |

| 20 | 54 ± 4 |

| 40 | 66 ± 3 |

| 60 | 76 ± 2 |

| 80 | 83 ± 3 |

| 100 | 84 ± 1 |

Figure 2.

Crystallization peak position for the hexagonal (squares) and the orthorhombic BaCl2 crystallization (circles) depending on the different Eu2+ and Eu3+ doping fractions. The heating rate was 5 K/min. Data for a Eu-free ZBLAN glass is shown for comparison.

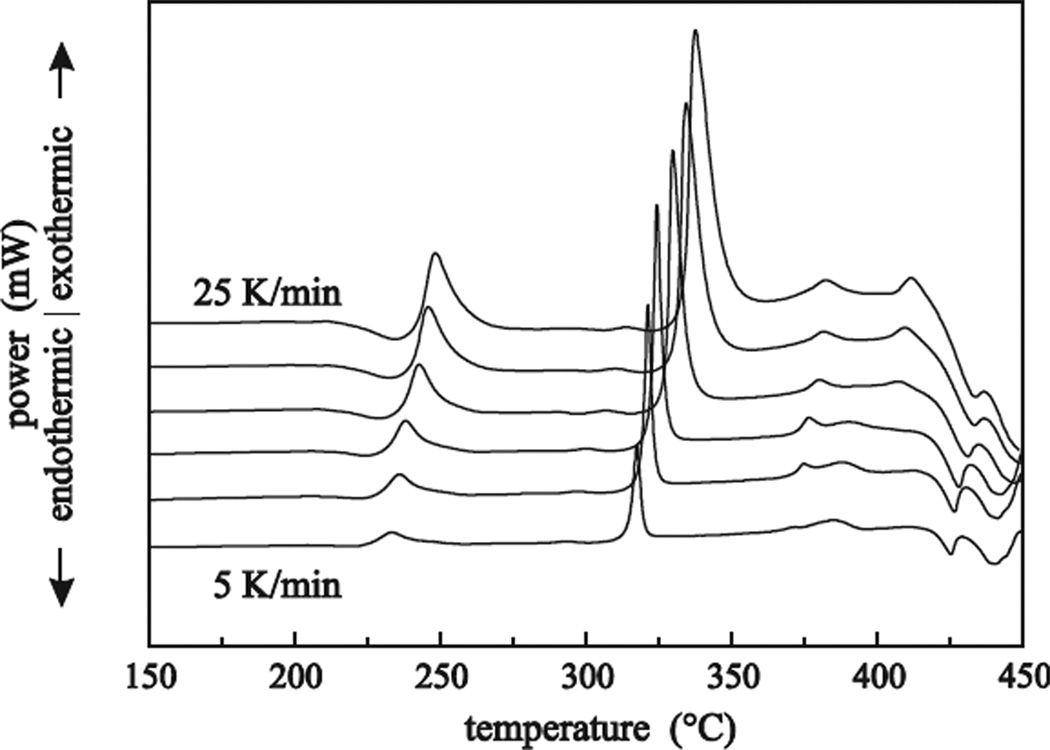

DSC measurements with different heating rates, α, enable the determination of the BaCl2 crystallization activation energy, Ea, by Kissinger’s method [12]:

| (1) |

where R is the gas constant. With higher heating rates the crystallizations are shifted to higher temperatures; their peak intensities are increased due to an enhanced heat flow dHc/dT into the samples (see Figure 3), which is given by the product

| (2) |

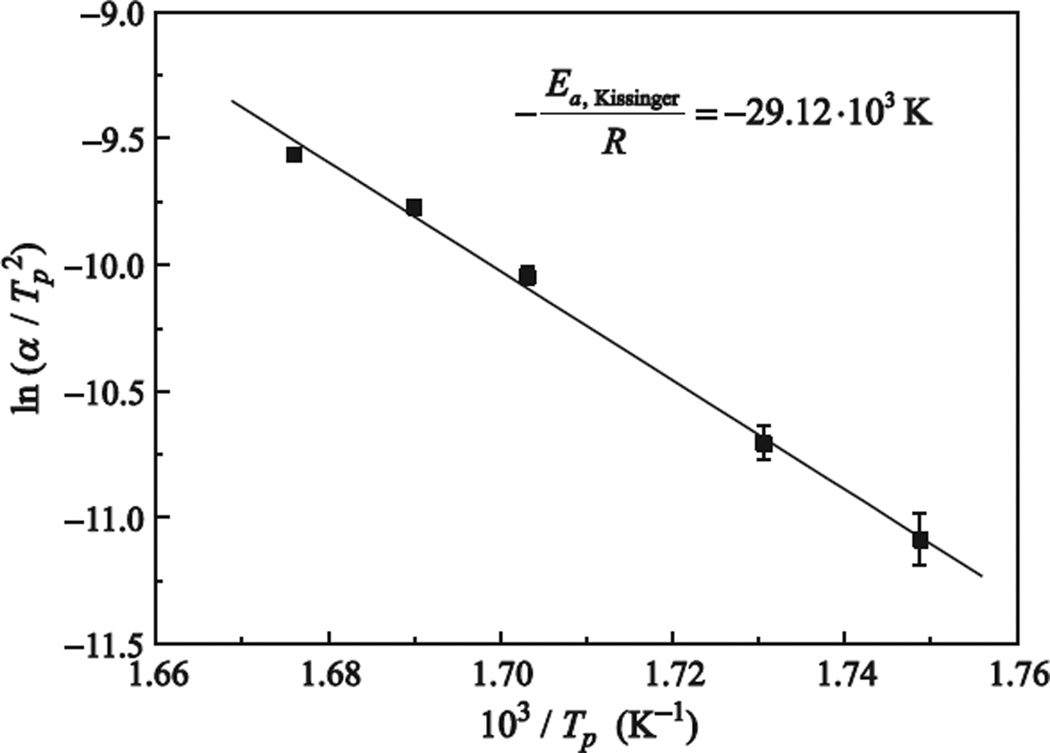

with the sample mass, m, the sample specific heat capacity, cp, and the constant heating rate, α. When plotting vs. (1/Tp) as shown in Figure 4, Ea can be obtained from the slope of the linear fit.

Figure 3.

Plot of the DSC data for the FCZ glass with a Eu2+ fraction of 80%. The different heating rates go from 5, 7.5 and 10 to 25 K/min in steps of 5 K/min. The curves are vertically displaced for clarity.

Figure 4.

Fit for the pure EuCl3-doped FCZ glass. The slope gives the apparent activation energy, Ea.

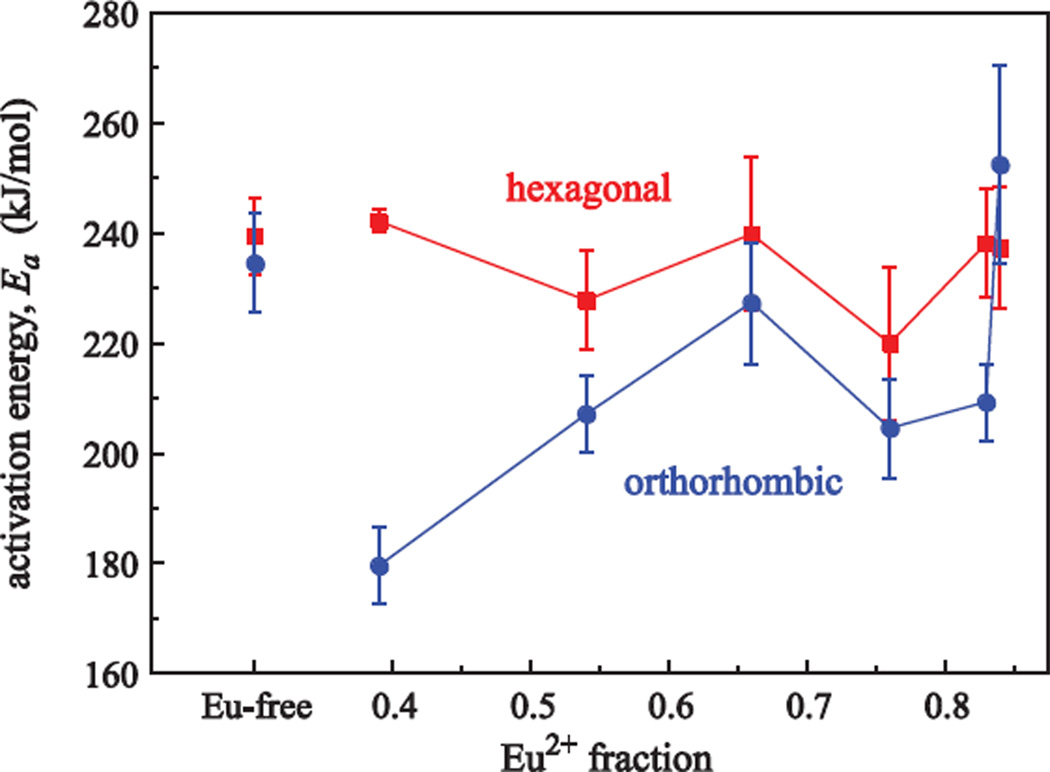

Figure 5 shows Ea versus Eu2+ and Eu3+ doping fraction. Ea of the hexagonal phase is not sensitive to different Eu oxidation states, but Ea of the hexagonal to orthorhombic phase transformation shows an increase with increasing Eu2+ amount, i.e., more energy is needed to initialize the transformation to orthorhombic crystal structure. However, some points trend down, likely caused by composition inhomogeneities from pieces coming from different sample positions.

Figure 5.

Activation energies, Ea, for the hexagonal (squares) and the orthorhombic (circles) BaCl2 crystallization obtained from the DSC data depending on the different Eu2+ and Eu3+ doping fractions. Data for a Eu-free ZBLAN glass is shown for comparison.

Compared to the pure EuCl2-doped FCZ glass (Cl/(Cl+F) = 15.22%) the available Cl/(Cl+F) amount in the melt is 0.6% higher for pure EuCl3 doping (15.81%), i.e., the small increase in the chlorine volume fraction for changing the Eu-doping from Eu2+ to Eu3+ could be the reason for the fact that the energy needed for the phase transformation decreases. Furthermore, photoluminescence measurements have shown that Eu2+ is incorporated into the BaCl2 nanocrystals, but Eu3+ is not [13]; Eu2+ substitutes for Ba2+ in BaCl2 [14]. A higher Eu2+ doping fraction probably results in a higher Eu2+ concentration in the nanocrystals causing an increase in the activation energy required for the hexagonal to orthorhombic phase transformation. Looking at the activation energies for the Eu-free ZBLAN, it is striking that the energies for both phases are within the error (Ea, hex. = 240 ± 7 kJ/mol and Ea, ortho. = 235 ± 9 kJ/mol), while there is a large difference between the hexagonal and the orthorhombic crystallization energy for the various Eu-doped samples (the maximum difference is 63 kJ/mol for an Eu2+ fraction of 0.39). This difference decreases with increasing Eu2+ fraction.

3.2. Rare-earth co-doping

Eu2+-doped glasses which are additionally doped with a further RE such as Gd, Nd, Yb, or Tb are interesting to investigate because of possible energy transfer processes between the two RE ions and potential effects on the luminescence properties. However, a further RE may also affect the BaCl2 crystallization which is investigated in detail below.

Figure 6 shows DSC data for the RE co-doped series and an undoped glass for comparison; the heating rate was 10 K/min. Besides the outlying crystallization peaks for the Gd3+-doped glass (see below), the shift of the main crystallization peak of the undoped sample to lower temperatures is striking. This crystallization was attributed to a partial crystallization of the glass matrix, namely the formation of β-BaZrF6 and NaZrF5 [15]. It confirms the recently found behavior that higher fluorine content (lower fluorine evaporation during the melting process) leads to a decrease in peak temperature and an earlier crystallization, because more fluorine increases the probability for the crystals to form. Since the undoped sample was made as the only 20 g batch (the others were 10 g batches) less mass% of fluorine was lost during the same melting process. This was established by ion chromatography measurements. The averaged crystallization temperature is 334 °C for the RE co-doped samples, while it is 313 °C for the undoped sample, i.e., the crystallization temperature is reduced by 21 °C. To give a clearer picture, the peak positions for hexagonal and orthorhombic phase crystallizations are also shown in Figure 7. As mentioned earlier for the multivalent Eu series, the temperature difference between both crystallization peaks slightly increases when the sample is doped with RE ions.

Figure 6.

Plot of the DSC data for FCZ glasses with different RE co-dopants. The heating rate was 10 K/min. Data for an undoped ZBLAN glass is shown for comparison and the curves are vertically displaced for clarity.

Figure 7.

Crystallization peak position for the hexagonal (squares) and the orthorhombic BaCl2 crystallization (circles) depending on the different RE dopants. The heating rate was 10 K/min. Data for an undoped ZBLAN glass is shown for comparison.

GdCl3 as a co-dopant for EuCl2 retards the nucleation and growth of BaCl2 nanocrystals the most, as both crystal phases crystallize at the highest temperatures (Tp1(Gd3+) = 247 °C, Tp2(Gd3+) = 311 °C). Compared to the other co-dopants the cause of this is thought to be the larger atomic radius of Gd3+ of about 233 pm (rTb = 225 pm, rYb = 222 pm and rNd = 206 pm) [16] resulting in a higher electro-negativity and higher probability to attract electrons towards the nucleus. Therefore, more energy is needed to break the bond between the Gd and Cl ions or to split off chlorine ions, which can then contribute to the crystallization and growth of more and larger BaCl2 nanocrystals. However, Nd3+ does not fit into this trend, since its crystallization peak temperatures are in between the peaks of Gd3+ and Tb3+ and not, as one would suggest from the atomic radius, at the lowest temperature of all co-dopants. This effect can be explained by former studies on Nd3+-doped FCZ glasses and glass ceramics which have shown that the optical transitions of the Nd ions are affected by the BaCl2 nanocrystal size leading to the conclusion that some of the Nd3+ ions, similar to Eu2+, are sitting in close proximity to the nanocrystals or possibly incorporated into them [4]. Thus, the interactions between Nd ions and the BaCl2 crystal lattice may lead to the higher BaCl2 crystallization temperature.

Looking at the crystallization activation energies in Figure 8, Gd3+ is once again outlying: Both hexagonal and orthorhombic crystallizations show a much lower activation energy than the undoped sample, especially for the orthorhombic crystallization with 160 kJ/mol compared to 235 kJ/mol for the undoped sample. Also, the difference in the activation energy of the hexagonal and orthorhombic crystallization is considerably larger: For Gd3+ it is 53 kJ/mol, while it is only 5 kJ/mol for the undoped sample. The difference decreases for the row Nd3+ (40 kJ/mol) via Tb3+ (17 kJ/mol) to Yb3+ (10 kJ/mol).

Figure 8.

Hexagonal (squares) and orthorhombic (circles) BaCl2 crystallization activation energies, Ea, obtained by Kissingers method [12] for different RE codopants. Data for an undoped ZBLAN glass is shown for comparison.

4. Conclusion

DSC measurements have shown that the crystallization of hexagonal phase BaCl2 is not very sensitive to different Eu oxidation states, while the hexagonal to orthorhombic phase transition shows increased activation energy, Ea, with increasing Eu2+ doping fraction.

In order to increase total luminescence yield, Eu2+-doped FCZ glasses were additionally doped with Gd, Nd, Yb, or Tb chlorides. Influence on the nanocrystallization such as retardation of nucleation and growth was observed. These crystallization shifts, in terms of temperature, could be attributed to the different atomic radii of the co-dopants associated with differences in electro-negativity. Gd3+ retarded nucleation and growth of BaCl2 nanocrystals the most as it has the largest atomic radius. Nd3+ did not fit into this trend, possibly due to stronger structural interactions between Nd ions and the BaCl2 crystal lattice, e.g. a possible incorporation into the nanocrystals; this was observed in previous work.

Future work will focus on the optical characterization of the RE co-doped glass ceramics as well as on a two-step annealing process, where in a first step as many nucleation grains as possible will be created, followed by an accurately defined growth to the desired crystallite size.

Highlights.

Nucleation and growth of BaCl2 in fluorozirconate-based glasses is investigated.

Eu-doping affects hexagonal to orthorhombic phase transformation.

Activation energy for phase transformation increases with increasing Eu2+ content.

Co-doping with trivalent rare-earth ions also affects BaCl2 nucleation and growth.

Acknowledgment

C. Paßlick and S. Schweizer would like to thank the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) for financial support within the Centre for Innovation Competence SiLi-nano® (Project No. 03Z2HN11). In addition, S. Schweizer was supported by the FhG Internal Programs under Grant No. Attract 692 034.

The sample synthesis was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) under Grant No. 5R01EB006145-02 and the characterization was supported under National Science Foundation Award # DMR 1001381. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Science Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnson JA, Schweizer S, Henke B, Chen G, Woodford J, Newman PJ, MacFarlane DR. Eu-activated fluorochlorozirconate glass-ceramic scintillators. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100:034701. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JA, Schweizer S, Lubinsky AR. A Glass-Ceramic Plate for Mammography. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90(3):693–698. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahrens B, Henke B, Miclea PT, Johnson JA, Schweizer S. Enhanced up-converted fluorescence in fluorozirconate based glass ceramics for high efficiency solar cells. Proc. of SPIE: Photonics for Solar Energy Systems II. 2008;7002:700206. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahrens B, Löper P, Goldschmidt JC, Glunz S, Henke B, Miclea PT, Schweizer S. Neodymium-doped fluorochlorozirconate glasses as an upconversion model system for high efficiency solar cells. physica status solidi (a) 2008;205(12):2822–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paßlick C, Henke B, Ahrens B, Miclea PT, Wenzel J, Reisacher E, Pfeiffer W, Johnson JA, Schweizer S. Glass-ceramic covers for highly efficient solar cells. SPIE Newsroom; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paßlick C, Ahrens B, Henke B, Johnson JA, Schweizer S. Crystallization behavior of rare-earth doped fluorochlorozirconate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2011;357(11–13):2450–2452. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2010.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacFarlane DR, Matecki M, Poulain M. Crystallization in fluoride glasses: I. Devitrification on reheating. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 1984;64(3):351–362. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulain M. Overview of crystallization in fluoride glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 1992;140:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber JKR, Vu M, Paßlick C, Schweizer S, Brown DE, E JC, A JJ. The oxidation state of europium in halide glasses. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2011;23:495402. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/23/49/495402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paßlick C, Müller O, Lützenkirchen-Hecht D, Frahm R, Johnson JA, Schweizer S. Structural properties of fluorozirconate-based glass ceramics doped with multivalent europium. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;110:113527. doi: 10.1063/1.3662148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aggarwal ID, Lu G, editors. Fluoride Glass Fibre Optics. London: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissinger HE. Reaction Kinetics in Differential Thermal Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957;29(11):1702–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweizer S, Hobbs LW, Secu M, Spaeth J-M, Edgar A, Williams GVM, Hamlin J. Photostimulated luminescence from fluorochlorozirconate glass ceramics and the effect of crystallite size. J. Appl. Phys. 2005;97:083522. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wever H, Den Hartog HW. EPR of BaCl2:Eu2+ and BaCl2:Gd3+ physica status solidi (b) 1975;70(1):253262. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baricco M, Battezzati L, Braglia M, Cocito G, Kraus J, Modone E. Crystallization behaviour of fluorozirconate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 1993;161:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clementi E, Raimondi DL, Reinhardt WP. Atomic Screening Constants from SCF Functions. II. Atoms with 37 to 86 Electrons. J. Chem. Phys. 1967;47:1300–1307. [Google Scholar]