Abstract

Background and Purpose

Women use their cumulative breastfeeding experiences, in combination with other factors, to make their infant feeding decisions. This pilot study assessed the reliability and predictive validity of the revised Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative (BBS-C).

Methods

25 women were recruited prenatally from a university hospital. The BBS-C was completed before hospital discharge. Infant feeding outcomes were measured at 1 and 3 months postpartum.

Results

Participants were 17–40 years old, mostly married, Whites, and well-educated. Coefficient alpha was .92–.94. The BBS-C predicted an infant not receiving breast milk, not feeding from the breast, and receiving infant formula feedings.

Conclusions

In this sample, the BBS-C had strong reliability and predictive validity. Further testing should assess reliability and predictive validity in a wider range of populations and settings.

Keywords: breastfeeding, nursing assessment, postpartum period, psychometrics

Most mothers in the United States (75%) begin breastfeeding immediately after birth, but by 6 months, only less than half of mothers are still breastfeeding (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Problems that cause women to give up on breastfeeding often start during the postpartum hospitalization (Taveras et al., 2003); and during the first 4 months of life, a peak in breastfeeding cessation occurs in the first week after birth (Ertem, Votto, & Leventhal, 2001). Therefore, it is critical that breastfeeding be adequately assessed and supported during the childbirth hospitalization because waiting 1 week or more after birth “is too late to intervene for many breastfeeding mothers” (Ertem et al., 2001, p. 546).

During postpartum hospitalization in the United States, registered nurses are the primary providers of care (Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, 2010) and mothers want their support when breastfeeding (Gill, 2001). To encourage women to continue breastfeeding, registered nurses must be able to accurately identify breastfeeding problems and use interventions that alleviate or minimize those problems during the postpartum hospitalization. It is critical that nurses assess how the mother perceives breastfeeding and problems associated with breastfeeding because mothers have a closer view of their infants, can feel the movements of their infant’s mouth, and can hear the faint sounds of swallowing and breathing (Nyqvist, Rubertsson, Ewald, & Sjödén, 1996). The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the preliminary psychometric properties of the Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative (BBS-C), a revised version of the Beginning Breastfeeding Survey (BBS) that measures a mother’s perception of all her breastfeeding experiences since giving birth, instead of measuring only a single breastfeeding episode.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs served as the conceptual framework for the original version of the BBS (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs states that human behavior is motivated by five sequential levels of needs: physiologic, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization (Maslow, 1943). Breastfeeding is a maternal behavior that can be motivated by a woman’s need to provide physiological nourishment to her infant; to keep her infant safe from infection and chronic disease; to establish a loving, intimate relationship; to achieve self-confidence in a maternal role; or to become the best mother she can be. Alternatively, a mother can stop breastfeeding to protect herself from nipple pain and fatigue, feeling exposed and vulnerable, being accused of having a sexual relationship with her infant, or being a bad mother who doesn’t provide enough nourishment to her infant. In either case, breastfeeding is motivated by maternal and infant needs; and assessing breastfeeding involves assessing how well a mother perceives that her and her infant’s needs are being met by breastfeeding (Mulder & Johnson, 2010).

BACKGROUND

Postpartum Hospitalization

Breast milk is preferred for infant feeding because it enhances the maturation of the gastrointestinal system (Blackburn, 2003) and has significant protective health benefits for mothers and infants (Ip et al., 2007). The postpartum hospitalization period is the most critical time for establishing breastfeeding and so is a critical window that affects the long-term health of an infant. To achieve effective breastfeeding, mothers and infants must learn how to cooperatively accomplish latching, sucking, and swallowing of a sufficient amount of breast milk at each feeding (Mulder, 2006). Mothers must also learn how to position their infant comfortably and how to encourage their infant to grasp enough of their breast to prevent nipple pain and trauma (Cadwell, 2007).

Breastfeeding problems that arise during the postpartum hospitalization affect how long an infant receives only breast milk or even any breast milk (Taveras et al., 2003). Almost one-quarter of breastfeeding mothers (21%) report serious or somewhat serious problems in breastfeeding during the 1–2 days after birth (Taveras et al., 2003). Examples of problems include difficulty latching the infant to the breast, nipple pain, and nipple trauma. Mothers who, during the postpartum hospitalization, have difficulty latching for half or more of feedings are significantly more likely to stop breastfeeding 7–10 days after birth (Mercer et al., 2010). Mothers who experience nipple pain or trauma are also significantly less likely to continue breastfeeding during the first 6 months after birth, even if the nipple pain is mild (Cernadas, Noceda, Barrera, Martinez, & Garsd, 2003). Furthermore, a woman’s risk of breastfeeding cessation correlates with her number of breastfeeding problems (Hauck, Fenwick, Dhaliwal, & Butt, 2010). Thus, breastfeeding assessment and support should be a priority during the postpartum hospitalization.

Breastfeeding Assessment

The advantages of using a structured tool to assess breastfeeding are (a) key clinical indicators that should be consistently assessed by all health care professionals, and (b) changes in specific indicators would be tracked over time (Weddig, Baker, & Auld, 2011). Although many structured tools have been developed to assess breastfeeding, they vary widely in purpose, concept, and targeted respondent (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). Despite this variety of tools, clinicians and researchers report that these tools have little in common with each other (Moran, Dinwoodie, Bramwell, & Dykes, 2000), and are either clinically unreliable (Riordan & Koehn, 1997) or require clinical testing and refinement in more diverse populations (Ho & McGrath, 2010). Furthermore, none of the existing tools reliably and validly measure the mother’s perception of breastfeeding effectiveness during the postpartum hospitalization (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). This gap in the clinical assessment of breastfeeding during the postpartum hospitalization led to the development of the BBS (Mulder & Johnson, 2010).

PROCEDURES FOR INSTRUMENT DEVELOPMENT

The BBS was developed to assess a mother’s perceptions of how effectively she is breastfeeding during the postpartum hospitalization (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). The BBS proved to be reliable and valid in an urban community hospital where the patient population was ethnically diverse (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). The internal consistency reliability of the BBS was 0.90, well above the minimum of 0.70 recommended by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). Lower scores on the BBS accurately predicted which mothers would give infant formula supplements or stop breastfeeding by 14–28 days after birth (Mulder & Johnson, 2010).

Despite these strengths, the BBS also had several limitations that supported the need for revision. The BBS was designed to measure a single breastfeeding session (Mulder & Johnson, 2010) to “measure changes in the mother’s perception of breastfeeding effectiveness over successive breastfeedings” (Mulder & Johnson, 2010, p. 333); yet, several women who completed the BBS wrote additional comments on the survey, explaining how their current breastfeeding session was different from previous breastfeeding sessions (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). These results suggested that breastfeeding sessions often vary considerably during the first 1–2 days after birth (Matthews, 1991); therefore, mothers evaluate their collective breastfeeding experience as opposed to a single breastfeeding session in isolation. Mercer and colleagues (2010) support the importance of measuring a mother’s collective breastfeeding experience, reporting that if a mother’s collective breastfeeding experience is assessed using the variables—(a) maternal age, (b) previous breastfeeding experience, © the number of episodes of latching difficulty, (d) the mean interval between breastfeeding, and (e) the number of bottles of supplementary infant formula given during the postpartum hospitalization—then her risk for stopping breastfeeding can be accurately predicted (Mercer et al., 2010). Therefore, the BBS was revised to change the focus to a mother’s cumulative breastfeeding experience instead of a single breastfeeding session and to improve reliability, clarity, and item fit with the tool. To differentiate the original and revised tools, the revised tool was named the Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative (BBS-C).

The BBS-C still measures the mother’s perception of breastfeeding effectiveness. The original BBS included items that were statements of positive or negative breastfeeding experiences and Likert-scale response options. The revised BBS-C reworded all of the positive and negative statements, so they included all of a mother’s breastfeeding experiences with the current newborn, and changed the response options so they were measured by a frequency scale (Table 1). Changing to the frequency scale resulted in one fewer response option (five responses instead of six), compared to the BBS.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the Beginning Breastfeeding Survey (BBS) and the Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative (BBS-C)

| Beginning Breastfeeding Survey (BBS) |

Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative (BBS-C) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Positive

breastfeeding items |

My baby eagerly opened his/her mouth wide |

My baby eagerly opens his/her mouth wide |

| My baby’s sucking felt strong | My baby’s sucking feels strong | |

| My baby sucked eagerly | My baby sucks eagerly | |

| I could hear my baby swallow | I can hear my baby swallow while breastfeeding |

|

| I felt comfortable | I feel comfortable when I am

breastfeeding |

|

| I felt calm and relaxed | I feel calm and relaxed while

breastfeeding |

|

| My baby enjoyed breastfeeding | My baby enjoys breastfeeding | |

| My baby was comforted by breastfeeding |

My baby is comforted by breastfeeding |

|

| I enjoyed breastfeeding my baby | I enjoy breastfeeding my baby | |

| I felt close to my baby | Item removed | |

| My baby became content and relaxed |

My baby is content and relaxed after breastfeeding |

|

| I knew what I needed to do to breastfeed my baby |

I know how to breastfeed my baby |

|

| Breastfeeding my baby was easy | Breastfeeding my baby is easy | |

| I felt confident about breastfeeding my baby |

I feel confident about breastfeeding |

|

|

Negative

breastfeeding items |

I felt unhappy about breastfeeding |

I feel unhappy about breastfeeding |

| My nipple(s) hurt | My nipples or breasts hurt so

much that I want to stop breastfeeding |

|

| My breasts were sore or tender | Item removed | |

| I felt exhausted | I feel so tired that I have

trouble staying awake to breastfeed |

|

| I worried about breastfeeding in front of people |

I feel embarrassed if I

breastfeed in front of other people |

|

| I was afraid I might feel nipple or breast pain |

I am afraid of feeling nipple or breast pain |

|

| My baby was fussy | My baby is fussy while

breastfeeding |

|

| My baby wasn’t interested in breastfeeding |

My baby doesn’t want to

breastfeed |

|

| My baby didn’t get enough milk |

My baby doesn’t get enough milk from breastfeeding |

|

| I felt frustrated trying to breastfeed |

I xsfeel frustrated while trying to breastfeed |

|

| I had trouble breastfeeding my baby |

I have trouble breastfeeding my baby |

|

| I wasn’t sure if I was breastfeeding the right way |

I am not sure if I am

breastfeeding the right way |

|

| Response options | Strongly disagree | Always |

| Moderately disagree | Usually | |

| Mildly disagree | Sometimes | |

| Mildly agree | Rarely | |

| Moderately agree | Never | |

| Strongly agree |

Note. Italics indicate revised wording in the BBS-C.

In addition, to improve the reliability of the BBS-C, two items from the BBS were removed; and to improve clarity and fit with the tool, other items were reworded (see Table 1). The item “I felt close to my baby” was removed because the corrected item– total correlation coefficient for this item had been less than .40, and when initially tested, responses to this item showed limited variation (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). The item “My breasts were sore or tender” was removed because the corrected item–total correlation coefficient had been less than .40 (Mulder & Johnson, 2010), and it could be combined with another item, resulting in the new item “My nipples or breasts hurt so much that I want to stop breastfeeding.” Seven items were reworded to clarify when the behavior indicated in the statement was occurring, such as “I can hear my baby swallow while breastfeeding” or “My baby is content and relaxed after breastfeeding.” Finally, when the BBS was initially tested, four items showed corrected item–total correlation coefficients that scored less than .40 (Mulder & Johnson, 2010), so these four were reworded to improve clarity and fit with the tool.

DESCRIPTION, ADMINISTRATION, AND SCORING OF THE INSTRUMENT

The BBS-C has 24 items, 13 worded positively and 11 worded negatively. Response options for all questions are a frequency scale with the options Always, Usually, Sometimes, Rarely, and Never. The BBS-C is administered during the childbirth hospitalization one or more times to allow registered nurses to assess a mother’s perception of breastfeeding effectiveness and provide interventions as appropriate.

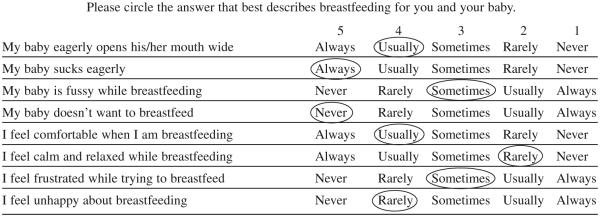

Total Cumulative Score

For the first method of scoring the BBS-C (total cumulative score), each item receives a value of 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 for a possible total score ranging from 24 to 120. The numerical score assigned to each response option for the individual items depends on whether the item is a positive or negative statement about a breastfeeding experience (see Figure 1). For items that are positive statements, such as “My baby sucks eagerly,” the response option Always was given a value of 5. For items that are negative statements, such as “I feel unhappy about breastfeeding,” a 5 was assigned to the response option Never. The numerical values for each item are summed to calculate the total cumulative score. Higher total cumulative scores on the BBS-C indicate greater breastfeeding effectiveness for the mother and the newborn.

Figure 1.

Example of item responses on the BBS-C.

Total Problem Score

The second method of scoring the BBS-C (total problem score) recodes items dichotomously with a “0” or “1” depending on the original score on the 5-point frequency scale. A recoded score of “1” represents an effective breastfeeding behavior, whereas a recoded score of “0” represents an ineffective breastfeeding behavior and a potential breastfeeding problem. Converting the 5-point response to a dichotomous response is done by assigning a “1” to items originally scored as “5” or “4” and a “0” to items originally scored as “3,” “2,” or “1.” The total problem score on the BBS-C is calculated by summing all of the items recoded as a “1.” Higher total problem scores indicate less effective breastfeeding.

For example, in Figure 1, of the eight items presented, a response option representing a score of 4 or greater was circled for five of the items. These answers indicate that the newborn is (a) opening his or her mouth to latch on to the breast (Usually = 4), (b) sucking eagerly (Always = 5), and © not refusing to breastfeed (Never = 5). The mother is (a) feeling comfortable while breastfeeding (Usually = 4) and (b) is not feeling unhappy about breastfeeding (Rarely = 4). In these areas, the mother and infant are achieving effective breastfeeding. Recoding these responses for the total problem score would result in all of these items being scored with a “0,” representing no problems.

A response option of 3 or less was circled for three of the items: the baby is sometimes fussy while breastfeeding (Sometimes = 3), the mother does not feel calm and relaxed while breastfeeding (Rarely = 2), and the mother sometimes feels frustrated while breastfeeding (Sometimes = 3). Recoding these responses for the total problem score would result in all of these items being scores with a “1,” representing three possible problems. These responses would suggest that the nurse caring for this mother and newborn should further assess why the newborn is sometimes fussy during breastfeeding and if the mother’s difficulty feeling calm and relaxed are caused by the newborn’s fussiness or another factor. Once these potential breastfeeding problems are identified and confirmed with the mother, the nurse can suggest breastfeeding interventions designed to alleviate or minimize these problems and increase breastfeeding effectiveness.

METHODS

The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the preliminary psychometric properties of the BBS-C. This study used a prospective, descriptive design. Institutional review board approval was received from the University of Iowa before beginning recruitment. Women were recruited during their third trimester of pregnancy and followed through birth and the first 3 months postpartum. Women were offered a $10 gift card to a local retail store for each survey completed.

Sample

Women were eligible to participate in this study if they were in their third trimester of pregnancy, planning on giving birth to their infants at the study hospital, and were considering breastfeeding. Women were excluded from further participation in this study if they were not admitted to the study hospital or they did not breastfeed at all during their postpartum hospitalization. A sample size of 25 women was used for this pilot study to identify preliminary reliability and validity and support future testing of this instrument.

Procedures

During a prenatal visit in their third trimester of pregnancy, women were recruited by a registered nurse researcher. Eligible women were approached and informed about the study. Women who chose to participate completed their informed consent and a short demographic questionnaire during their prenatal visit. At this time, contact information including mailing address, telephone number, and e-mail address (when available) was also obtained. Participants were given the BBS-C and an opaque envelope to take with them to the hospital when they gave birth. Participants were instructed to complete the BBS-C on their last postpartum hospitalization day and return the completed survey to a research nurse.

Research nurses screened admission records from Monday to Friday during the study period to determine if any of the participants had been admitted and given birth. Participants admitted to the postpartum unit after giving birth were approached by the research nurse, reminded to complete the BBS-C during their final day of hospitalization, and, if necessary, given an extra copy of the BBS-C if they had forgotten their original copy. Research nurses met with participants as necessary to answer questions and collect the completed BBS-C surveys.

Participants were contacted by mail or e-mail at 1 and 3 months postpartum to complete the Infant Feeding Survey, which measured infant feeding method and breastfeeding problems. Participants who did not complete the online or paper Infant Feeding Survey received up to two telephone reminder calls. During the telephone reminder calls, participants were given the option of completing the Infant Feeding Survey by phone.

Reliability Assessments

Internal consistency reliability was assessed for the BBS-C, calculated for each type of scoring method. Because the BBS-C is only completed by the breastfeeding mother, the assessment of interrater reliability was not necessary. The assessment of test–retest reliability was not done because the BBS-C is theorized to measure breastfeeding effectiveness, which is a changeable state during the course of breastfeeding. During the postpartum hospitalization, infants are expected to gradually achieve effective breastfeeding with differences in breastfeeding effectiveness between breastfeeding episodes. To assess internal consistency reliability, coefficient alpha and item–total correlation coefficients were calculated.

Predictive Validity

The purpose of the BBS-C is to identify women with less effective breastfeeding and more breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization, which increases their risk for breastfeeding termination or infant formula supplementation in the future. Therefore, the most important measure of validity for the BBS-C is predictive validity. To assess trends indicative of predictive validity, Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare BBS-C total cumulative scores and total problem scores obtained during the postpartum hospitalization with future infant feeding outcomes at 1 and 3 months postpartum. The authors theorized that women with more effective breastfeeding and fewer breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization would be more likely to (a) be giving some breast milk, (b) be feeding directly from the breast, and (c) not be giving infant formula supplements than women with less effective breastfeeding and more breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization. The Mann–Whitney U test was selected because of the small total sample and unequal group sizes.

Outcome Measures

Outcome variables for this study were measured with the Infant Feeding Survey, a self-report survey developed by the author for this study. The three outcome variables were no breast milk, no direct breastfeeding, and formula supplementation. The conceptual and operational definitions of the outcome variables are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Outcome Variables and Questions on the Infant Feeding Survey

| Outcome | Operational Definition | Infant Feeding Survey Question |

|---|---|---|

| No breast milk | Infant not receiving any breast milk in the past week |

In the past week, have you breastfed your baby directly from your breast? Yes or No and In the past week, have you fed your baby your breast milk in a bottle, cup, or other feeding device? Yes or No |

| No direct breastfeeding | Infant not feeding directly from the breast in the past week |

In the past week, have you breastfed your baby directly from your breast? Yes or No |

| Formula supplementation | Infant receiving one or more feedings of infant formula in any amount during the past week |

In the past week, have you fed your baby infant formula? Yes or No |

Mothers completed the Infant Feeding Survey via the Internet, a paper-mailed survey, or by telephone at 1 and 3 months postpartum. The questions asked on all three versions of the survey were the same, and are listed in Table 2. In addition to completing the Infant Feeding Survey, mothers who completed paper surveys by mail were also asked to evaluate the ease of use and understandability of the Infant Feeding Survey questions at 1 month postpartum. All 14 mothers who evaluated the Infant Feeding Survey indicated that it was easy to fill out, they understood all of the questions and could choose answers that described how they were feeding their infants.

DEMOGRAPHIC AND CHILDBIRTH VARIABLES

Demographic variables were obtained from the mother with a short questionnaire completed when she enrolled in the study during a prenatal visit in her third trimester of pregnancy. A chart abstraction was done by the principal investigator after the mother and infant were discharged from the hospital to obtain childbirth variables, including parity, delivery method, and infant gender.

RESULTS

There were 25 women recruited prenatally. Research nurses were able to contact most of the women who were eligible to participate in the study (90.6%). Of the women contacted, most enrolled in the study (86.2%). The women ranged in age from 17 to 40 years, with a mean age of 30.8 years (SD = 5.4). The sample was overwhelmingly composed of married (88%), White women (92%) with a bachelor’s degree or higher education (72.0%). Roughly half of the women were employed during their pregnancy (56.0%). Most of the women (56.0%) planned to return to work when their infant was 6–11 weeks old, whereas 24.0% did not plan on working after giving birth and 20.0% planned on returning to work when their infant was 12 weeks or older. Most participants (64.0%, n = 16) preferred paper-mailed surveys for the 1- and 3-month Infant Feeding Surveys, whereas 9 participants (36%) chose to complete their surveys on the Internet after receiving an Internet link by e-mail.

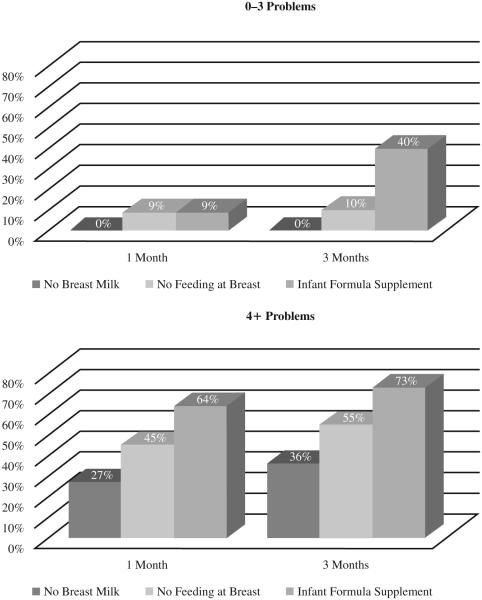

One of the recruited participants dropped out of the study because she gave birth at a hospital other than the study hospital. About half of the remaining 24 participants were primigravidas (46%, n = 11); and parity for the multigravida participants (n = 13) ranged from 0 to 2. Two-thirds of the participants gave birth vaginally and more than half of the infants were male (63%). At 1 month postpartum, 22 of the 25 enrolled participants (88%) completed the Infant Feeding Survey. At 3 months postpartum, 21 of the 22 enrolled participants (84%) completed the Infant Feeding Survey. The feeding outcomes at 1 and 3 months postpartum are presented in Figure 2, separated by the number of breastfeeding problems that mothers experienced during the birth hospitalization. The two groups of 0–3 problems and 4 or more problems were formed by dividing the sample at the median number of problems (M = 3.5).

Figure 2.

Feeding outcomes at 1 and 3 months postpartum according to the number of breastfeeding problems during birth hospitalization.

Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative

The mean BBS-C total cumulative score was 96.1 (SD = 12.1) with a range of 72–112. The mean BBS-C total problem score was 5.5 (SD = 6.0) with a range of 0–19. Most mothers (83.0%) had one or more potential breastfeeding problems when the BBS-C was recoded to compute the total problem score. Four mothers had no potential breastfeeding problems. The item that was most often a potential problem (50.0%) was “I feel so tired that I have trouble staying awake to breastfeed.” The item “I can hear my baby swallow while breastfeeding” was scored as a potential problem by 37.5% of participants, indicating that 37.5% of the participants sometimes, rarely, or never heard their baby swallow while breastfeeding. The item that was least often scored as a potential problem was “I enjoy breastfeeding my baby” (4.2%).

Reliability

The internal consistency reliability of the BBS-C was assessed with coefficient alpha. Coefficient alpha for the BBS-C using the 5-point response option format (total cumulative score) was .94. Corrected item–total correlations ranged from .384 to .824. Only one item, “I’m afraid of feeling nipple or breast pain,” had a corrected item–total correlation of less than .40.

Coefficient alpha for the BBS-C when the responses were recoded to dichotomous variables was .92. Corrected item–total correlations ranged from .232 to .899. Four items had corrected item–total correlations of less than .40 (“My baby’s sucking feels strong”; “I enjoy breastfeeding my baby”; “My nipples or breasts hurt so much that I want to stop breastfeeding”; and “I feel so tired that I have trouble staying awake to breastfeed”).

Predictive Validity

Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare BBS-C cumulative total scores and BBS-C total problem scores for the three outcome variables (see Tables 3 & 4). At 1 month postpartum, the group of women whose infants did not receive breast milk, did not feed directly from the breast, or received one or more infant formula supplements in the prior week had a significantly lower mean BBS-C total score and higher mean BBS-C problem count score than the other group. At 3 months postpartum, the group of women whose infants did not receive breast milk or did not feed directly from the breast had a significantly lower mean BBS-C total score and higher BBS-C problem count than the other group. At 3 months postpartum, the group of women whose infants received one or more infant formula supplements in the prior week had a lower mean BBS-C total score, but the difference was not significant.

TABLE 3.

Comparing BBS-C Total Cumulative Scores for Infant Feeding Outcome Variables at One and Three Months Postpartum

| Variable | n | Mean Score (SD) |

Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No breast milk (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 77.67 (4.62) | 3.00 | 9.00 | 3.0 | .015 |

| No | 19 | 98.42 (10.31) | 12.84 | 244.00 | ||

| No direct breastfeeding (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 82.33 (12.10) | 5.33 | 32.00 | 11.00 | .006 |

| No | 16 | 100.56 (7.70) | 13.81 | 221.00 | ||

| Formula supplement (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 8 | 85.75 (12.83) | 7.00 | 56.00 | 20.00 | .014 |

| No | 14 | 101.21 (7.35) | 14.07 | 197.00 | ||

| No breast milk (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 76.25 (4.72) | 2.50 | 10.00 | .000 | .002 |

| No | 17 | 100.12 (8.51) | 13.00 | 221.00 | ||

| No direct breastfeeding (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 7 | 83.86 (11.75) | 5.57 | 39.00 | 11.00 | .005 |

| No | 14 | 101.43 (7.85) | 13.71 | 192.00 | ||

| Formula supplement (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 90.58 (13.69) | 9.04 | 108.50 | 30.50 | .095 |

| No | 9 | 102.22 (6.24) | 13.61 | 122.50 | ||

Note. BBS-C = Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative.

TABLE 4.

Comparing BBS-C Total Problem Scores for Infant Feeding Outcome Variables at One and Three Months Postpartum

| Variable | n | Mean Score (SD) |

Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | U | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No breast milk (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 15.33 (4.62) | 19.67 | 59.00 | 4.00 | .018 |

| No | 19 | 4.32 (5.11) | 10.21 | 19.00 | ||

| No direct breastfeeding (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 13.33 (6.47) | 17.58 | 105.50 | 11.50 | .007 |

| No | 16 | 3.00 (2.85) | 9.22 | 147.50 | ||

| Formula supplement (1 month) | ||||||

| Yes | 8 | 11.50 (6.53) | 16.81 | 134.50 | 13.50 | .004 |

| No | 14 | 2.57 (2.68) | 8.46 | 118.50 | ||

| No breast milk (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 16.25 (2.75) | 19.25 | 77.00 | 1.00 | .003 |

| No | 17 | 3.59 (3.87) | 9.06 | 154.00 | ||

| No direct breastfeeding (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 7 | 12.14 (6.69) | 16.36 | 114.50 | 11.50 | .005 |

| No | 14 | 2.93 (3.00) | 8.32 | 116.05 | ||

| Formula supplement (3 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 8.83 (6.94) | 13.38 | 160.50 | 25.50 | .042 |

| No | 9 | 2.22 (1.86) | 7.83 | 70.50 | ||

Note. BBS-C = Beginning Breastfeeding Survey-Cumulative.

DISCUSSION

Findings

The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the psychometric properties of the BBS-C. This study benefited from the high participation (86.2%) and retentions rates at birth (96.0%), 1 month (88.0%), and 3 months (84.0%); the combination of methods used to collect data and encourage women to continue participating may have contributed to the high participation and retention rates. A second strength of this study was prenatal recruitment of participants. Prenatal recruitment, as opposed to postpartum recruitment, guarded against participation bias based on a woman’s feelings about how well she is breastfeeding. During postpartum recruitment for the previous study of the BBS, several women who refused to participate in the study spontaneously indicated that they did not want to participate because they and their infants were not breastfeeding very well (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). Therefore, the mothers and infants in this study are expected to have experienced wide variability in breastfeeding effectiveness.

Reliability

The BBS-C demonstrated an internal consistency reliability of 0.94 for the 5-point response option scoring and 0.92 for the recoded dichotomous response option coding, both of which are higher than the 0.90 reliability achieved with the first version of the BBS (Mulder & Johnson, 2010). The internal consistency reliability of the BBS-C is also above the minimum recommendation of 0.70 for use in research and 0.90 for clinical use (DeVon et al., 2007). However, the reliability of an instrument is specific only to the sample which has been tested (DeVon et al., 2007) and the sample of women in this study were primarily Whites, married, and well-educated. Therefore, additional testing of the BBS-C in larger and more diverse populations is needed before the BBS-C can be recommended for clinical use.

Predictive Validity

The BBS-C demonstrated predictive validity when scored with both the 5-point response options and the recoded dichotomous response options. Lower total cumulative scores and higher total problem scores were significantly associated with mothers not giving any breast milk, not feeding directly from the breast, and giving infant formula supplements at 1 month postpartum. Lower total cumulative scores and higher total problem scores were significantly associated with mothers not giving any breast milk and not feeding directly from the breast at 3 months postpartum, whereas higher total problem scores were significantly associated with giving infant formula supplements at 3 months postpartum. These results support the original hypotheses that women with more effective breastfeeding and fewer breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization would be more likely to (a) give some breast milk, (b) feed directly from the breast, and (c) not give infant formula supplements than women with less effective breastfeeding and more breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization.

These results also agree with previous research indicating that a woman’s breastfeeding experiences and problems during the postpartum hospitalization have lasting effects on her ability to continue any and exclusive breastfeeding (Mercer et al., 2010; Taveras et al., 2003). Previous studies have indicated that events occurring during the birth hospitalization affect long-term breastfeeding exclusivity and duration. Breastfed infants who receive infant formula supplements during the birth hospitalization are significantly less likely to continue breastfeeding, even if their mothers intended to breastfeed exclusively (Declercq, Labbok, Sakala, & O’Hara, 2009; Forde & Miller, 2010).

LIMITATIONS

This study was conducted as a pilot study to assess the feasibility of a larger study. As such, no power analyses had been conducted, yet the differences in BBS-C scores according to feeding type at 1 and 3 months were significant. However, the small sample size limits the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. The convenience sample of 24 women obtained for this study may not be representative of the larger population from which they were selected. In addition, the sample was ethnically homogenous and well-educated; with most of the participants being Whites, married, and college educated. Therefore, the strongest conclusion that can be drawn from this research is that further research is necessary to confirm the findings reported here.

An additional limitation is that this study relied primarily on maternal self-report. Breastfeeding is a socially desirable and emotionally charged activity, and as such, mothers may have been biased toward selecting positive statements about breastfeeding on the BBS-C or indicating that they were still breastfeeding or breastfeeding exclusively when they were not actually doing so. Mothers have reported feeling pressured by hospital staff to breastfeed and blamed when they were unable to breastfeed exclusively or gave infant formula supplements (Rudman & Waldenström, 2007). To reduce the occurrence of social desirability bias, the BBS-C and the Infant Feeding Survey were self-administered, because respondents are more likely to report sensitive information when they complete the survey rather than the survey being administered by an interviewer (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

The BBS-C, a revised version of the BBS, demonstrated improved reliability and strong predictive validity in a small, homogenous sample of women. The internal consistency reliability of the BBS-C ranged from 0.92 to 0.94, depending on the scoring method. Total cumulative scores and total problem scores from the BBS-C were significantly related to infant feeding outcomes during the first 3 months after birth. These results support further testing in larger and more diverse samples of women and across various hospitals that provide maternity care. Research may also investigate how a mother’s perception of breastfeeding effectiveness may change over time—such as during postpartum hospitalization or in the first month after birth—to determine if there are patterns of breastfeeding problems that emerge or resolve over time. Further research should also consider the best way to incorporate the BBS-C into the clinical nursing care of breastfeeding mothers and infants during the postpartum hospitalization.

The BBS-C is a short tool that can be completed by mothers during the brief postpartum hospitalization as part of a daily assessment of breastfeeding. Once further research confirms cutoff scores indicative of low breastfeeding effectiveness, nurses can use the BBS-C scores to identify women who need additional breastfeeding support through nursing interventions or referral to a lactation consultant. Furthermore, review of the individual item answers on the BBS-C allows nurses or lactation consultants to identify specific breastfeeding problems, discuss those problems with mothers, and offer tailored interventions for those problems. The advantage of the BBS-C, as compared to using only a visual assessment of breastfeeding, is that the BBS-C asks mothers how they feel about breastfeeding, which cannot be directly observed and may not be offered spontaneously. Mothers who appear to be breastfeeding effectively may be silently suffering from insecurity about their breastfeeding skills or doubt about whether they are fulfilling their infant’s nutritional and emotional needs with breastfeeding. Thus, the BBS-C has the potential to (a) help registered nurses identify breastfeeding problems during the postpartum hospitalization,(b) promote timely and tailored interventions by nurses or lactation consultants, and(c) increase the likelihood of mothers to be successfully and exclusively breastfeeding.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Gamma Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau and the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science at the University of Iowa. This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1RR024979 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

REFERENCES

- Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses . Guidelines for professional registered nurse staffing for perinatal units. Author; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn S. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal physiology. A clinical perspective. 2nd Saunders; St. Louis, MO: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell 2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Provisional rates of any and exclusive breastfeeding by age among children born in 2007. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding /data/NIS_data/2007/age.htm.

- Cernadas J, Noceda G, Barrera L, Martinez A, Garsd A. Maternal and perinatal factors influencing the duration of exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life. Journal of Human Lactation. 2003;19:136–144. doi: 10.1177/0890334403253292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E, Labbok M, Sakala C, O’Hara M. Hospital practices and women’s likelihood of fulfilling their intention to exclusively breastfeed. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:929–935. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVon H, Block M, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst D, Hayden S, Lazzara D, Kostas-Polston E. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem I, Votto N, Leventhal J. The timing and predictors of the early termination of breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2001;107:543–548. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde K, Miller L. 2006-07 north metropolitan Perth breastfeeding cohort study: How long are mothers breastfeeding? Breastfeeding Review. 2010;18(2):14–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. The little things: Perceptions of breastfeeding support. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck Y, Fenwick J, Dhaliwal S, Butt J. A western Australian survey of breastfeeding initiation, prevalence and early cessation patterns. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;15:260–268. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y, McGrath J. A review of the psychometric properties of breastfeeding assessment tools. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2010;39:386–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip, et al. 2007.

- Maslow H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50:370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M. Mothers’ satisfaction with their neonates’ breastfeeding behaviors. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1991;20:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1991.tb01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer A, Teasley S, Hopkinson J, McPherson D, Simon S, Hall R. Evaluation of a breastfeeding assessment score in a diverse population. Journal of Human Lactation. 2010;26:42–48. doi: 10.1177/0890334409344077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran V, Dinwoodie K, Bramwell R, Dykes F. A critical analysis of the content of the tools that measure breast-feeding interaction. Midwifery. 2000;16:260–268. doi: 10.1054/midw.2000.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder 2006.

- Mulder P, Johnson T. The beginning breastfeeding survey: Measuring mothers’ perceptions of breastfeeding effectiveness during the postpartum hospitalization. Research in Nursing & Health. 2010;33:329–344. doi: 10.1002/nur.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. 3rd McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nyqvist K, Rubertsson C, Ewald U, Sjödén P. Development of the preterm infant breastfeeding behavior scale (PIBBS): A study of nurse-mother agreement. Journal of Human Lactation. 1996;12:207–219. doi: 10.1177/089033449601200318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan J, Koehn M. Reliability and validity testing of three breastfeeding assessment tools. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1997;26:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman A, Waldenström U. Critical views on postpartum care expressed by new mothers. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:178–191. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras E, Capra A, Braveman P, Jensvold N, Escobar G, Lieu T. Clinician support and psychological risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics. 2003;112:108–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:859–883. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weddig J, Baker S, Auld G. Perspectives of hospital-based nurses on breastfeeding initiation best practices. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2011;40:166–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]