Summary

The aim of this work is to review the relationship between the function of the masseter muscle and the occurrence of malocclusions. An analysis was made of the masseter muscle samples from subjects who underwent mandibular osteotomies. The size and proportion of type-II fibers (fast) decreases as facial height increases. Patients with mandibular asymmetry have more type-II fibers on the side of their deviation. The insulin-like growth factor and myostatin are expressed differently depending on the sex and fiber diameter. These differences in the distribution of fiber types and gene expression of this growth factor may be involved in long-term postoperative stability and require additional investigations. Muscle strength and bone length are two genetically determined factors in facial growth. Myosin 1H (MYOH1) is associated with prognathia in Caucasians. As future objectives, we propose to characterize genetic variations using “Genome Wide Association Studies” data and their relationships with malocclusions.

Keywords: Masseter muscle, Humans, Phenotype, Genotype, Mal-occlusion

Introduction

Anatomical distortions in jaw growth falling within the “normal” or non-syndromic variation of facial features can cause malocclusions of teeth, which are severe enough to require orthodontic treatment, as well as orthognathic surgery, to restore normal occlusion. But we still do not have a good understanding of the aetiology of these malocclusions nor of the causes of post-surgical relapse occurring in some patients. A candidate cause contributing to both problems is the contractile activity of the jaw-closing muscles which act on the craniofacial skeleton. In this article, we summarize the historical background to this argument, and consider more recent works which have shown clear associations between aspects of jaw muscle composition reflecting contractile activity, and malocclusion.

Muscle function alters craniofacial form

Historically, the aetiology of some forms of human malocclusion, and orthodontic treatment philosophy, were attributed to the anatomic position of jaw closing muscles and subsequent force vectors acting on the skeleton during crucial periods of facial growth, tooth eruption and dental alveolar development [1]. Because of limitations on the kind of experimental approaches that can be used on human subjects, there have been many studies of the effects of altered mastication on craniofacial shape in animals, and in general these show quite substantial changes [2]. Kiliaridis et al. demonstrated that growing rats fed with a consistency diet exhibit morphological changes in areas of muscle insertions with local bone remodeling and a shift in the muscle fiber type composition, although no alteration in the fiber diameter [2]. Exercising masseter muscles unilaterally in growing rats resulted in severe modification of the skull, dento-alveolar complex and in malocclusion on the affected side [3]. Nanda et al. [4] employed a surgical procedure to reposition the masseter muscle unilaterally on nine young dogs: this produced angular changes and loss of antegonial notch on the operated side. More recently, similar effects have been obtained by altered expression of myostatin (GDF-8) which is the principal factor that negatively regulates muscle fiber growth [5]. In mouse gene, knock-out experiments that render myostatin non-functional, masticatory muscles become much larger, cranial vault shape changes and the jaw takes on a “rocker shape” [6]. Rocker shape jaws are seen in some populations at puberty due to increased muscular force with growth [7]. The mandible loses the antigonial notch and the angle becomes more convex in appearance [8]. Overall, these studies all point to the conclusion that there is an influence of masticatory muscle function on craniofacial growth.

Similar conclusions can be reached from studies of patients with pathological muscular disorders. Progressive weakness of the mandibular elevator muscles (as in Duchenne muscular dystrophy) leads to a downward and backward rotation of the mandible away from the maxilla with a resultant long face deformity and open bite [9]. Excessive muscle contraction can also restrict craniofacial growth. This effect is seen most clearly in torticollis, a twisting of the head caused by excessive tonic contraction of the neck muscles on one side, primarily the sternocleidomastoid. The result is facial and cranial asymmetry because of growth restriction on the affected side, which can be quite severe unless the contracted neck muscles are surgically detached at an early age [10]. Ingervall and Bitsanis [11] studied the effect of daily chewing exercises over a one year period on children with developmental features of long face morphology. The results showed a significant increase in maximum bite force and the majority of the children also showed an upward and forward growth rotation of the mandible over the review period, which could be described as normalization of the facial growth. Maximum bite forces are probably not relevant here, since they are too infrequent; by contrast, light continuous forces from respiratory and postural functions and other repetitive activities are of the appropriate intensity and duration to activate surface deposition and resorption of bone, and certainly have the potential to modify craniofacial skeletal dimensions over the long term.

Masticatory muscle function and fiber type composition

Skeletal muscle is composed of fibers that exist in functionally and biochemically distinct phenotypes. In fibers of a given type, the sarcomeric thick filaments are composed of the same isoform of myosin heavy chain (the main motor protein). Different isoforms of myosin confer different contractile activity to fibers, which therefore differ in their shortening speed and in tension cost (force produced per ATP molecule consumed) [12]. Human jaw-closer muscles express both neonatal (developmental) and atrial (α-cardiac) myosin isoforms in addition to type-I (slowest and most economic), type-IIA (fast and intermediate in tension cost) and type-IIX (fastest and least economic) isoforms [13]. Furthermore, many human masticatory muscle fibers have a hybrid myosin content ranging from two to almost all possible combinations of isomyosins [14]. Finally, human jaw-muscles are also unusual in that there is a tendency for many of the type-II muscle fibers to be very small in diameter, whereas in most limb muscle they are a similar in size or even larger than the type-I fibers.

Since the first histochemical discovery of the intermediate (IM) fibers, the later realization that they were a form of hybrid fiber [15], and the subsequent discovery of other hybrid phenotypes in human masseter, there has been speculation about their significance. In limb muscle a significant increase in the proportion of hybrid fibers containing both fast and slow myosins is usually a response to changes in activity, yet the presence of hybrid fiber types in masseter is so common that it can be regarded as ‘normal’. Ringqvist [16] observed that the frequency of IM fibers in masseter was higher in patients with poor occlusion than in those with good occlusion.

Stability in surgical correction of jaw deformations

Given the large number of surgical options and the necessity to determine the long-term effects of skeletal muscle on treatment outcome, retrospective clinical trials have sought to characterize the relative stability of intervention. For the most part, these procedures are relatively stable, but in 15 to 20% there is a relapse which is often noticeable to the patient and clinically significant. It is still difficult to predict which subjects will have clinically significant relapse. Muscle adaptation may be a key factor in post-surgical instability. Following orthognathic surgery to correct prognathic or retrognathic mandibles, changes have been observed in myosin isoform expression [17] and in expression of the muscle growth factors that regulate fiber size (IGF–I and myostatin) [18]. In future studies, muscle adaptation and growth factor expression changes will need to be compared between stable and unstable surgical results.

Vertical dimension malocclusions are a particular problem. Altering the vertical dimension of the face remains one of the greatest clinical challenges, with a multitude of orthodontic, orthopedic and surgical interventions recommended for the correction of associated skeletal, dental and neuromuscular abnormalities. During sagittal splitting of the mandible, the vertical dimension may be augmented by cutting the pterygo-masseteric sling to help positioning mandibular angle in a lower position [19]. Nonetheless, increasing the vertical dimension is much more difficult to achieve and maintain than modifying the sagittal dimension. In the future, advances in treatment planning for vertical dimension problems may come from a better understanding of how variability in jaw closing muscle phenotype contribute to post-treatment stability.

Associations between masseter muscle composition and malocclusion

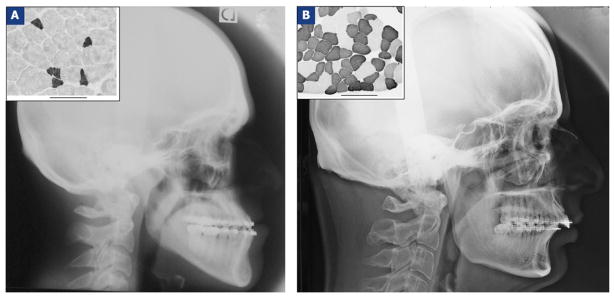

We have investigated the relation between these features by analysis of small samples of masseter muscle obtained at the time of orthognathic surgery for correction of malocclusion. The main experimental approaches used were histological (especially immunostaining) and more recently gene expression studies and genotyping. In an initial pilot study of 44 patients [14], we measured the mean fiber area and number of the four main fiber types present (types-I, I/II hybrid, II and neonatal/atrial), from which we could also calculate fiber type ‘occupancy’ (percentage of the muscle area occupied by a given fiber type). The main result was that an increase in vertical jaw dimension correlated with a decrease in the occupancy of type-II fibers as illustrated in fig. 1 and table I. Another observation was that there is a very wide variability between subjects, and a power analysis based on the pilot data predicted the need for a much larger subject population to describe all interactions between variances in fiber type and craniofacial form, especially the weaker phenotypic associations [14].

Figure 1.

Lateral cephalograms taken before orthognathic surgery in two subjects: one from the class III open bite group (A) and one from the class II deep bite group (B). The insert boxes (top left) show examples of immunostaining analysis of the masseter muscle samples of these subjects based on fast myosin isoform content: dark staining indicates type-II fibers and pale staining type-I fibers. The scale bar is 100 micrometers in both cases.

Table I.

Comparison of fiber type composition of masseter in one open and one deep bite subject. These patients correspond to the two whose radiographs are shown in Fig. 1. Note especially the difference in type-II occupancy between subjects (grey background).

| Patients | Masseter muscle fiber type occupancy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-I | Type-I/II | Type-II | Type neo-atrial | |

| A (open bite) | 83.51 | 11.96 | 0.22 | 4.31 |

| B (deep bite) | 33.30 | 4.94 | 61.76 | 0.00 |

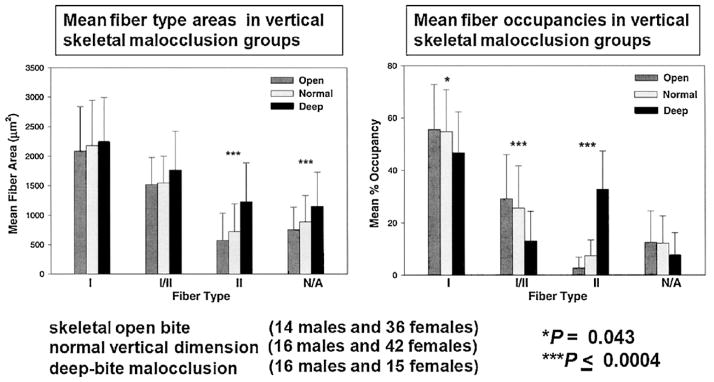

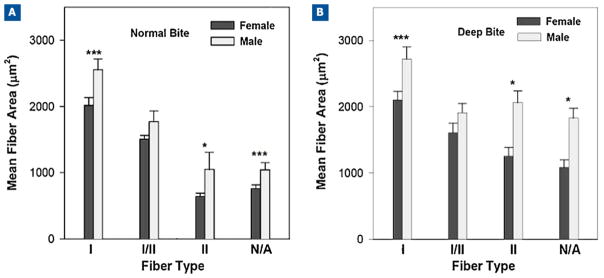

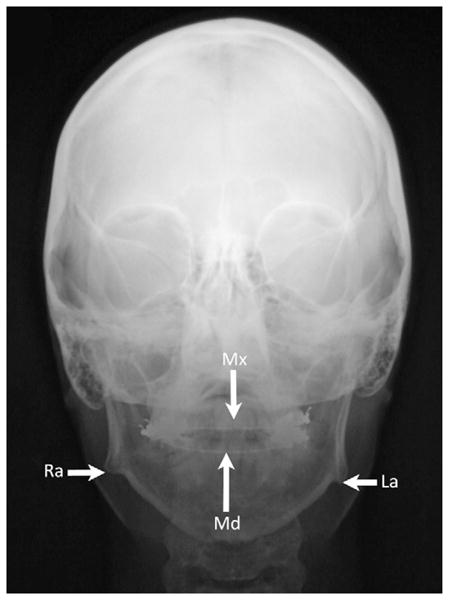

More recently, using a much larger subject population, we were able to confirm and extend the original observation regarding the consistent association of size and number of type-II fibers in masseter muscle with open or deep bite malocclusion, and demonstrate some other significant associations (fig. 2). This expanded population demonstrated that fibers of the same type tended to be larger in males than in females as shown in fig. 3, and that the time course of fiber size increase with age was different for males and females [20]. This population also showed that nearly 50% of patients had some significant lateral asymmetry. We therefore also analyzed masseter muscle composition at the same anatomical position on both sides in 24 patients with, and 26 without, lateral asymmetry [1]. Differences in left and right ramus length were also found to correlate with differences in type-II occupancy, with significant increases in type-II fibers occupancy on the same side as the deviation side (fig. 4 and table II). By contrast, symmetric patients had no significant differences in average fiber diameter or percent occupancy between left and right masseter muscle samples.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean fiber areas (left) and occupancies (right) of masseter muscle fiber types in male and female subjects by vertical skeletal malocclusion groups. Data from skeletal open bite (14 males and 36 females), normal vertical dimension (16 males and 42 females), and deep-bite malocclusion categories (16 males and 15 females). Bars represent one standard deviation of the mean. Significant differences are indicated by the asterisks as indicated.

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean fiber areas of masseter muscle fiber types in male and female subjects by vertical skeletal malocclusion groups. Data for mean fiber area values in μm2 for normal vertical dimension (16 males and 42 females) and deep-bite malocclusion categories (16 males and 15 females). Bars represent one standard deviation of the mean, and the significance of the difference between males and females is indicated by the asterisks: *P < 0.05; ***P less than or equal to 0.0004.

Figure 4.

Anteroposterior cephalogram showing lateral deviation of the mandible’s midline (Md) towards the right side and compared to the maxilla’s midline (Mx). The right mandibular ramus (Ra) is also “shorter” than the left mandibular ramus (La).

Table II.

Occupancies for the fiber types in masseter of one skeletal open bite subject whose cephalogram is shown in Fig. 4. Note the difference in type-II occupancy between left and right sides in this subject (grey background), who had a mandibular dental midline to the right side.

| Side | Masseter muscle fiber type occupancy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-I | Type-I/II | Type-II | Type neo-atrial | |

| Right | 47 | 32 | 18 | 3 |

| Left | 72 | 22 | 4 | 12 |

Interestingly, there are also fiber type differences between orthognathic surgery patients who have temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) signs and symptoms compared to those who do not. In 34 of patients who had facial asymmetry, comparison of fiber type composition between sides showed type-II fiber occupancy was increased in subjects with TMD and hybrid fiber occupancy was increased in subjects without TMD [1].

In another pilot study using samples from the orthognathic surgery patient study, we have also examined the expression of two key paracrine muscle growth regulators to see if these could explain the well-documented differences in fiber sizes (cross-sectional area) in masseter compared to limb muscles, and in male versus female masseter as observed not only by us but also by other authors [21]. Relative expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGf-I) and myostatin in masseter samples was different from the expression in limb muscle, and significant sex differences were observed [20].

In conclusion, our findings based on the expanded patient population of 139 subjects are that:

vertical facial dimension is related to fiber type composition (with an increase in type-II in deep bite cases);

facial asymmetry is common in dentofacial deformities patients, and shows the same relationship between vertical dimension and fiber type composition (type-II increased on the ‘short’ side);

there are some gender differences in masseter muscle fiber sizes;

sagittal facial dimension shows little relation to masseter fiber type composition. These fiber types and their contractile activity pattern provide a mechanism by which the compressive forces of muscle function can influence mechano-transduction and modeling of bone to produce jaw deformation phenotypes seen in malocclusion.

Genetic influences

Recent genome wide association studies with large subject populations demonstrate that both muscle size and height are highly heritable anthropometric traits [22,23]. So we are interested in identifying any gene variations that might provide information about mechanisms leading to dentofacial deformations. Evidence that this approach can be successful comes from a recent discovery that a G allele of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs10850110 in the myosin 1H (MYO1H) gene is over-represented in a European ancestry population with prognathism, which is a condition of the sagittal facial dimension [24].

Future directions

Our collective results demonstrate that vertical and transverse facial bone growth is closely associated with variations in masticatory muscle functional properties. Since general heritability estimates for muscle strength are quite high (more than 80%), genetic contributions to growth of both jaw bones and jaw muscles are important determining factors in the etiology of malocclusion [24]. Future directions will need to include translational genetics to understand the clinically significant relationships between growth and function of muscular and skeletal components of the face. Because genetic variations of the MYO1H gene are now of major interest, we have begun an investigation of its expression and possible correlation to dentofacial deformities. Unlike class II myosins which are responsible for muscle contraction, class I myosins are ‘unconventional’ single-headed myosin monomers involved in regulation of membrane dynamics, intracellular vesicle transport and inner ear auditory function. In humans, eight class I myosin genes, designated MYO1A to MYO1H, act as tension-sensors that respond to load changes by altering their ATPase and mechanical properties [25], although MYO1H has yet to be assigned a specific cellular function. Nevertheless, association of MYO1H with mandibular prognathism suggests that it may participate in aspects of musculoskeletal development to affect sagittal jaw deformation and malocclusion.

As a first step toward the identification of MYO1H function in dentofacial properties, we have compared its expression in human limb and masseter muscle, using samples obtained from three patients of the orthognathic surgery population described above. We used a sequence of the gene which did not include areas with single nucleotide polymorphisms in order to study gene expression rather than genetic variation. Malocclusion classification of subjects was based upon jaw dimension repositioning required in the surgical treatment plan. All three of the masseter muscles were from individuals diagnosed as normal in the vertical facial dimension. Two of the subjects were class II and one subject was class III in the sagittal dimension. The limb muscle RNA had been obtained with approval from earlier studies and banked for comparative use in masseter muscle studies. MYO1H was detected at low but quantifiable amounts in total RNA from commercial preparations of human thymus and from biopsies of limb and masseter muscle. Averaged data are shown in fig. 5.

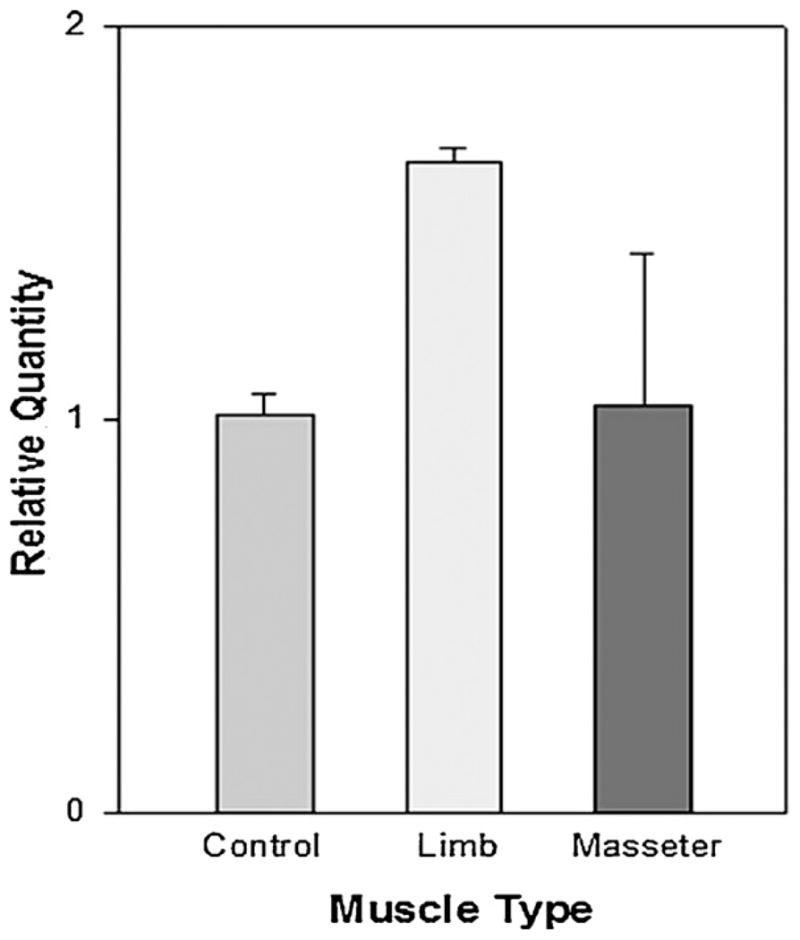

Figure 5.

Average relative expression of MYO1H in human muscle RNA. Data was determined from 3 assays, done in triplicate, for RNA from a commercial preparation of skeletal muscle (control), limb muscles (limb; n = 4) and masseter muscles (masseter; n = 3). Thymus RNA was the calibrator used in calculation of relative quantities and by definition had a value of 1.0. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

The high standard error for masseter muscle resulted from the wide variability that was seen between the three samples (values ranged from 0.41 to 1.98 relative quantity of gene expression), with the lowest MY01H expression in the class III patient. So, it appears that MYO1H genotype and gene expression in muscle may be important factors in the development of sagittal jaw malocclusions, although a much larger sample size will be required to confirm this possibility.

To conclude, there are clearly relationships between jaw discrepancies and both masseter muscle composition (various phenotypic properties, at least some of them potentially exerting their effects via muscle contractile activity impinging on skeletal structures) and some genotypes (for example MYO1H), although in this case the potential mechanism for its effects are not known. Recent advances in the methods used for phenotype and genotype analysis offer exciting possibilities both for revealing the biological mechanisms underlying the development of malocclusions, and as diagnostic tools to identify patients at risk of post-surgical relapse, thereby contributing to the improved treatments in the future.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a review lecture entitled “Malocclusions and Muscle Fibre Histomorphology” given at the 47th meeting of the “Société française de stomatologie et chirurgie maxillo-faciale” in September 2011, by Sciote JJ, Versailles, France.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

References

- 1.Raoul G, Rowlerson A, Sciote J, Codaccioni E, Stevens L, Maurage CA, et al. Masseter myosin heavy chain composition varies with mandibular asymmetry. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:1093–8. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182107766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiliaridis S, Engström C, Thilander B. Histochemical analysis of masticatory muscle in the growing rat after prolonged alteration in the consistency of the diet. Arch Oral Biol. 1988;33:187–93. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(88)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horowitz SL, Shapiro HH. Modification of skull and jaw architecture following removal of the masseter muscle in the rat. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1955;13:301–8. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330130208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanda SK, Merow WW, Sassouni V. Repositioning of the masseter muscle and its effect on skeletal form and structure. Angle Orthod. 1967;37:304–8. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1967)037<0304:ROTMMA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vecchione L, Byron C, Copper GM, Barbano T, Hamrick MW, Sciote JJ, et al. Craniofacial morphology in myostatin-deficient mice. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1068–72. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall DS, Snow CE. An evaluation of polynesian craniology. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1956;14:405–27. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330140316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houghton P. Rocker jaws. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1977;47:365–9. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330470303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckardt L, Harzer W. Facial structure and functional findings in patients with progressive muscular dystrophy (Duchenne) Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:185–90. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minamitani K, Inoue A, Okuno T. Results of surgical treatment of muscular torticollis for patients greater than 6 years of age. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:754–9. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingervall B, Bitsanis E. A pilot study of the effect of masticatory muscle training on facial growth in long-face children. Eur J Orthod. 1987;9:15–23. doi: 10.1093/ejo/9.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bottinelli R, Reggiani C. Human skeletal muscle fibres: molecular and functional diversity. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;73:195–262. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sciote JJ, Rowlerson AM, Hopper C, Hunt NP. Fibre type classification and myosin isoforms in the human masseter muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1994;126:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowlerson A, Raoul G, Daniel Y, Close J, Maurage CA, Ferri J, et al. Fiber-type differences in masseter muscle associated with different facial morphologies. Am J Orthop Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringqvist M, Ringqvist I, Eriksson PO, Thornell LE. Histochemical fibre-type profile in the human masseter muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1982;53:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ringqvist M. Size and distribution of histochemical fibre types in masseter muscle of adults with different states of occlusion. J Neurol Sci. 1974;22:429–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(74)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harzer W, Worm M, Gedrange T, Schneider M, Wolf P. Myosin heavy chain mRNA isoforms in masseter muscle before and after orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maricic N, Stieler E, Gedrange T, Schneider M, Tausche E, Harzer W. MGF- and myostatin-mRNA regulation in masseter muscle after orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:487–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferri J, Ricard D, Genay A. Posterior vertical deficiencies of the mandible: presentation of a new corrective technique and retrospective study of 21 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sciote JJ, Horton MJ, Rowlerson AM, Ferri J, Close JM, Raoul G. Human masseter muscle fiber type properties, skeletal malocclusions, and muscle growth factor expression. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuxen A, Bakke M, Pinholt EM. Comparative data from young men and women on masseter muscle fibres, function and facial morphology. Arch Oral Biol. 1999;44:509–18. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, Berndt SI, Weedon MN, Rivadeneira F, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beunen G, Thomis M. Gene driven power athletes? Genetic variation in muscular strength and power. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:822–3. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tassopoulou-Fishell M, Deeley K, Harvey EM, Sciote J, Vieira AR. Genetic variation in myosin 1H contributes to mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laakso JM, Lewis JH, Shuman H, Ostap EM. Myosin I can act as a molecular force sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]