Abstract

Adoptive immunotherapy using natural killer (NK) cells has been a promising treatment for intractable malignancies; however, there remain a number of difficulties with respect to the shortage and limited anticancer potency of the effector cells. We here established a simple feeder-free method to generate purified (>90%) and highly activated NK cells from human peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Among the several parameters, we found that CD3 depletion, high-dose interleukin (IL)-2, and use of a specific culture medium were sufficient to obtain highly purified, expanded (∼200-fold) and activated CD3−/CD56+ NK cells from PBMCs, which we designated zenithal-NK (Z-NK) cells. Almost all Z-NK cells expressed the lymphocyte-activated marker CD69 and showed dramatically high expression of activation receptors (i.e., NKG2D), interferon-γ, perforin, and granzyme B. Importantly, only 2 hours of reaction at an effector/target ratio of 1:1 was sufficient to kill almost all K562 cells, and the antitumor activity was also replicated in tumor-bearing mice in vivo. Cytolysis was specific for various tumor cells, but not for normal cells, irrespective of MHC class I expression. These findings strongly indicate that Z-NK cells are purified, expanded, and near-fully activated human NK cells and warrant further investigation in a clinical setting.

Saito and colleagues report on a simple feeder-free method for the generation of purified (>90%) and highly activated natural killer (NK) cells from human peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Almost all of the NK cells derived by this method express lymphocyte activation markers and are capable of lysing cells in tumor-bearing mice in vivo.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells play a crucial role during the innate immune responses, and as such form part of the body of immunological defense against various diseases, including infectious diseases and malignancies (Caligiuri, 2008). NK cells originate from hematopoietic stem cell progenitors in the bone marrow and are characterized and enriched as CD56+/CD3− lymphocytes in humans (Freud and Caligiuri, 2006). For some time now, NK cells have been believed to kill target cells that lack the expression of self MHC class-I molecules, a concept known as the “missing-self” hypothesis (Ljunggren and Karre, 1990; Karre, 2002). Recently, however, NK cells have also been shown to be capable of a spontaneous MHC-unrestricted cytotoxic response through an array of activating and inhibitory receptors (killer immunoglobulin-like receptors [KIRs]; Natarajan et al., 2002; Biassoni et al., 2003). It has been widely accepted that ex vivo manipulations of pure and activated NK cells are a good candidate method for a cellular therapeutic modality because of the critical role of NK cells in tumor progression (Komaru et al., 2009) and the impaired activity or reduced number of NK cells in patients with advanced malignant disease (Lahat et al., 1989; Chuang et al., 1990; Aparicio-Pagés et al., 1991; Brittenden et al., 1996; Gonzalez et al., 1998; Kishi et al., 2002; Kondo et al., 2003); however, development of NK cell-based immunotherapeutics has been much delayed because of the practical difficulties in producing highly purified and activated NK cell populations.

The initial clinical research on cell-based adoptive immunotherapeutics against advanced malignancies, which were conducted from the mid-1980s to early 1990s, extensively examined lymphokine-activated killer cells, consisting principally of activated T-lymphocytes and a relatively small amount of NK cells (Grimm et al., 1982; Rosenberg, 1985); however, a good clinical outcome could not be demonstrated for these treatments in several well-controlled clinical trials (Rosenberg et al., 1993; Law et al., 1995). Subsequently, adoptive immunotherapy using NK cells against malignancies was initiated (Koehl et al., 2004), and the majority of several clinical studies used haploidentical (Rubnitz et al., 2010; Geller et al., 2011) or KIR-negative NK cells (NK-92; Arai et al., 2008) mainly combined with interleukin (IL)-2 infusion to expand these cells in vivo, based on an important study suggesting the role of donor NK cell alloreactivity in mismatched transplants (Ruggeri et al., 2002). However, the clinical responses of these studies have been unsatisfactory, and thus further efforts will be needed.

Development of ex vivo expansion and activation of NK cells has been extensively assessed by groups at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Leung et al., 2005), the National Institutes of Health (Berg et al., 2009), Singapore (Suck et al., 2011), and the Karolinska Institute (Sutlu et al., 2010). These methods have generally been based on CD56-positive selection with or without CD3-depletion/CD3-suppression followed by IL-2 and/or IL-15 stimulation, and in some case virus-infected feeder cells have been used to obtain highly activated NK cells. Early studies demonstrated relatively low cytolysis, and although recent techniques have greatly improved this activity, these methods are still relatively complex. Therefore, there is still need of a simple protocol to generate highly activated NK cells in a clinical setting.

For these reasons, we here focused on the development of a simple technique—ideally, a feeder-free method—for expanding highly activated and purified NK cells. Among the several parameters examined by other groups, we found that only CD3-depletion, high-dose IL-2, and use of a specific culture medium were sufficient to obtain the highly purified and activated NK cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which we designated zenithal-NK (Z-NK) cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female NOD/SCID mice (6 weeks old) were obtained from KBT Orientals Co., Ltd. (Tosu-city, Saga, Japan) and kept under specific pathogen-free and humane conditions. The animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University. These experiments were also done in accordance with recommendations for the proper care and use of laboratory animals and according to The Law (No. 105) and Notification (No. 6) of the Japanese Government.

Cell lines

The K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line and the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines DLD-1 and SW620 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassass, VA). The PC-3 human prostatic carcinoma cell line was provided by Dr. Ichikawa (Department of Urology, Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine). The human lung giant cell carcinoma cell line Lu99, the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line PC-14, and the normal human embryonic lung fibroblast line MRC-5 were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank. The normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland). These cell lines were maintained in complete medium (RPMI-1640 for K562, DLD-1, PC-3, Lu-99, and PC-14; Leiboviz's L-15 medium for SW620; and RITC80-7 for MRC-5) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. HUVECs were cultured by using an EGM-2 Bullet Kit (Lonza).

Sample preparation

Written informed consent was obtained from all healthy volunteers in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Under approval of the institutional ethical committee (Approved No. 22-176) of Kyushu University, peripheral blood samples were collected from healthy volunteers. PBMCs were isolated by gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), and were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA. The purified primary NK cells used as controls were obtained by an NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). CD3-depleted PBMCs (CD3-PBMCs) were obtained by using Dynabeads CD3 (Invitrogen Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway). CD14- or CD19-depleted PBMCs (CD14-PBMCs or CD19-PBMCs) were obtained by using biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) CD14 or CD19 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) followed by Dynabeads Biotin Binder (Invitrogen Dynal AS).

NK cell expansion and activation

Primary NK cells, PBMCs, CD3-PBMCs, CD14-PBMCs, and CD19-PBMCs were cultured in six-well plates (Nalge Nunc International K.K., Tokyo, Japan) at a concentration of 5×105 cells/mL in KBM501 (containing high IL-2 [2813 IU/mL]), human serum albumin 2000 mg/L, and kanamycin sulfate 60 mg/L; Kohjin Bio, Saitama, Japan) and RPMI1640 (Wako, Osaka, Japan), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Life Technologies Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Life Technologies Japan, Ltd.), CellGro stem cell growth medium (SCGM; CellGenix, Freiburg, Germany), and Stemline II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing IL-2 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ; 2500 IU/mL) with 5% heat inactivated donor's autoserum for 14 days. Fresh medium was added every 4–5 days throughout the culture period. During medium replenishment, the cell concentration was adjusted to 5×105 cells/mL. Total cell numbers were assessed by staining cells with trypan blue dye on days 0, 5, 7, 9, and 14 of culture. The CD3−/CD56+ percentage was determined by flow cytometry on days 0, 7, and 14. Also, primary NK cells and NK cells cultivated for 14 days were observed under a light microscope CKX41 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with DP20 (Olympus).

Flow cytometric analysis

NK cells were first incubated in PBS with 10% heat-inactivated human AB-type serum to block nonspecific binding at 4°C for 10 min. Then, cells were stained with the following FITC-, PE-, PE-Cy5, PerCP-Cy5.5, or APC-conjugated mAbs: CD3, CD14, CD19, CD56, CD69, CD94, CD158f (KIR2DL5), CD314 (NKG2D), CD335 (NKp46), CD337 (NKp30), CD16, CD158b (KIR2DL3) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and CD158e/k (KIR3DL1/DL2) (Miltenyi Biotec).

In intracellular staining, the cell surfaces were stained with FITC- or PE-conjugated anti-CD3 and PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD56 mAbs. Then, the cells were permeabilized and fixed using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Fixation/Permeabilization kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Thereafter, cells were stained with FITC-conjugated Granzyme B (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and APC-conjugated Perforin (Biolegend).

The appropriate conjugated isotype-matched IgGs were used as controls. Cells were analyzed using a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with FlowJo 7.6 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Interferon-γ expression

NK cells were washed twice in serum-free IMDM and were co-incubated with K562 target cells at a ratio of 2:1 in a final volume of 200 μL in an MPC-treated 96-well round-bottom microplate (low-cell binding U96 with lid; Nalge Nunc International K.K.) in the presence of BD GolgiPlug protein transport inhibitor containing brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 hr. The cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD3-FITC and anti-CD56-PerCP-Cy5.5 or the corresponding isotype-matched IgGs at 4°C for 30 min. Thereafter, the cells were washed in PBS and permeabilized and fixed by using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Fixation/Permeabilization kit (BD Biosciences). Then, the cells were stained with anti-interferon (IFN)-γ-PE (Biolegend) or isotype-matched IgG at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were washed, resuspended in PBS, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytolytic assay

For the evaluation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity, NK cells cultivated for 14 days were used as effector cells. The evaluation of the effect of T cells on the cytotoxicity of NK cells was done according to the following protocol. The purified primary T cells were obtained from Dynabeads Untouched Human T-cells (Invitrogen Dynal AS). Then, the NK cells were co-cultured with primary T cells at a ratio of 1:5 in a 12-well plate for 16 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2. Thereafter, the number of NK cells among the total cells was assessed by flow cytometry and was taken as the number of effector cells. K562 target cells were labeled with 3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiOC18; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; final concentration: 0.01 mM) for 10 min at 37°C and 5% CO2, then washed three times with PBS. Effector cells were washed twice with IMDM and co-cultured with target cells at a ratio of 2:1, 1:1, 1:5, or 1:10 in an MPC-treated 96-well round-bottom microplate for 2 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were then washed with PBS and labeled with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD; Sigma-Aldrich; final concentration: 5 μg/mL) for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were again washed, resuspended in PBS, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry. The green fluorescence, obtained by labeling K562 cells with DiOC18, permitted discrimination between effector cells and target cells. Among gated target cells, the red fluorescence, obtained with 7AAD staining, enabled the differentiation between dead and live target cells. The results were expressed as the percentage of specific lysis using the following formula: (% of target cell lysis in the test−% of spontaneous cell death)/(% of maximum lysis−% of spontaneous cell death)×100. Spontaneous cell death was determined by incubation of K562 target cells in the cell culture medium alone, followed by 7AAD staining after harvest. For maximum lysis, target cells were fixed and permeabilized with 1% formaldehyde or treated with 1% Triton-X100 and also labeled with 7AAD.

Analysis of NK-cell degranulation

Primary and Z-NK cells were washed twice in IMDM and then co-incubated with K562 target cells at a ratio of 2:1, 1:1, 1:5, or 1:10 in a final volume of 200 μL in an MPC-treated 96-well round-bottom microplate at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 hr. Thereafter, the cells were stained with anti-CD107a-FITC (Biolegend), anti-CD3-PE, or anti-CD56-PE-Cy5 mAbs or the corresponding isotype-matched IgGs at 4°C for 30 min. The cells were then washed, resuspended in PBS, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

The effect of cryopreservation on the function of expanded NK cells

Expanded NK cells were cryopreserved in KBM501 supplemented with 5% human serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide or Cell Banker (Juji Field, Tokyo, Japan) at (2–5)×106 cells/mL over 7 days. Cells were thawed at 37°C, then slowly diluted with 5–10 mL of RPMI1640 or KBM501. Thawed cells were used for the expansion experiments and in the cytotoxicity assays and cell viability assays.

Evaluation of anti-tumor effects in vivo

K562 cells (1×107) were inoculated subcutaneously into the left flank of mice. Mice were subjected to one intravenous administration of PBS or primary NK cells (1×106 cells) or Z-NK cells (5×105 or 1×106 cells) via the tail vein at 4 days after K562 inoculation. The purified primary NK cells were obtained by an NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and were washed three times in PBS. Also, Z-NK cells were harvested and washed three times in PBS. For all injections, the materials were suspended in a 150-μL volume of PBS. The tumor volume was assessed using microcalipers every 3 to 4 days after the inoculation of K562 cells according to the formula: tumor volume (mm3)=S2xL/2, where L and S indicate the size in millimeters of the longest and shortest part, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the means±SEM, and were evaluated statistically by Mann–Whitney test, Scheffe's method, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test when appropriate. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined using the Tukey–Kramer method. The survival curves were determined using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare curves between the study and control groups. A probability value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Depletion of CD3+ cells is essential to expand highly purified NK cells

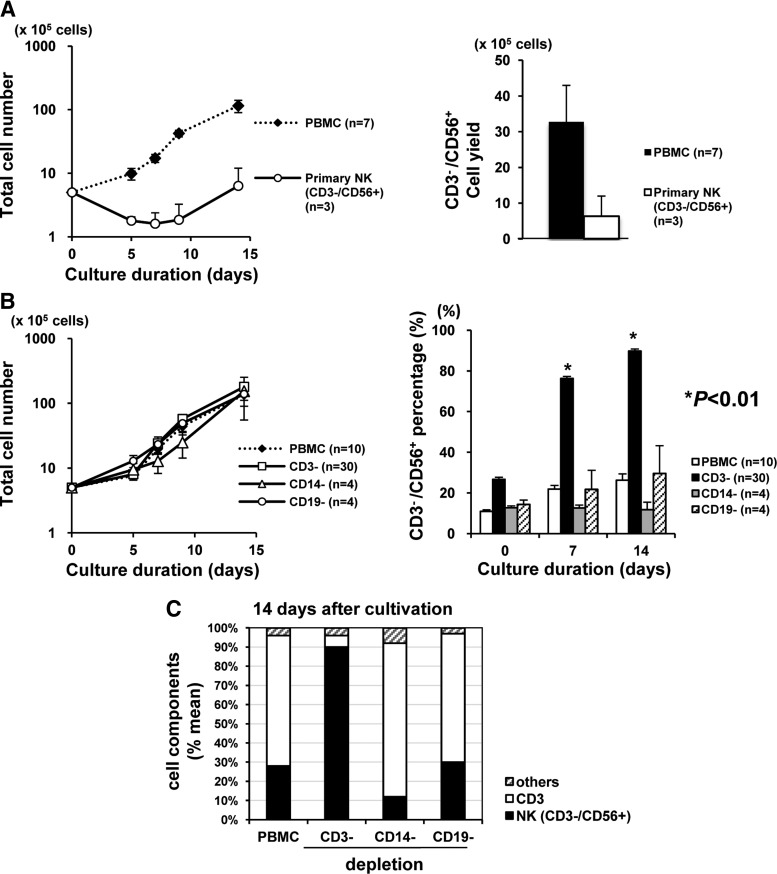

Before optimizing the parameters that were minimally required to expand the purified NK cells, we first asked which was better as a starting material, “crude” PBMCs or “pure” CD3−/CD56+-NK cells. As a culture medium, we used KBM501, an optimized medium containing high IL-2 (2813 IU/mL). As shown in Fig. 1A, PBMCs started to proliferate logarithmically soon after cultivation, but the proliferation of pure CD3−/CD56+-NK cells was much delayed (Fig. 1A, left graph). Thus the mean total yield of CD3−/CD56+-NK cells on day 14 was 3.3×106 cells from PBMCs (mean purity=24%) and 5.0×105 cells from pure NKs (mean purity=96%) (Fig. 1A, right graph).

FIG. 1.

Depletion of CD3+ cells is essential to natural killer (NK) cell–specific expansion. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by gradient centrifugation, using Ficoll-Paque PLUS. The purity of primary NK cells was ≥96%. The data are expressed as the means±SEM. (A) Growth curve of the total and selected primary CD3−/CD56+ NK cells (left graph), and final yield of CD3−/CD56+ NK cells at day 14 (right graph). Note the log scale on the left graph. (B) Growth curve of the total cells (left graph) and the time course of the CD3−/CD56+ cell percentage (right graph) during the culture periods of various materials (CD3−: CD3-depleted PBMCs; CD14−: CD14-depleted PBMCs; and CD19−: CD19-depleted PBMCs). Note the log scale on the left graph. (C) Mean ratio of cell components at 14 days of cultivation from each material shown in (B).

These findings suggested that (1) there might be a non-NK components in PBMCs that support NK cell proliferation and (2) there might be cell components that are more sensitive to IL-2. To test this hypothesis, we next performed a similar experiment using PBMCs depleted of some major cell subsets, namely CD3 (mainly T lymphocytes), CD14 (mainly monocytes/macrophages), or CD19 (mainly B lymphocytes), as the starting materials. Interestingly, no significant difference was observed in the proliferation curves of total cells in any starting material (Fig. 1B, left graph); FACS analyses demonstrated that a spontaneous increase of the %CD3−/CD56+ NK subset was seen only when using PBMCs depleted of CD3 (Fig. 1B, right graph). That is, over 90% of CD3−/CD56+ NK cells could be expanded only from CD3-depleted PBMCs, and other groups showed CD3 cell expansion on day 14 (Fig. 1C), indicating that depletion of the CD3 subset was essential to selectively expand CD3−/CD56+ NK cells.

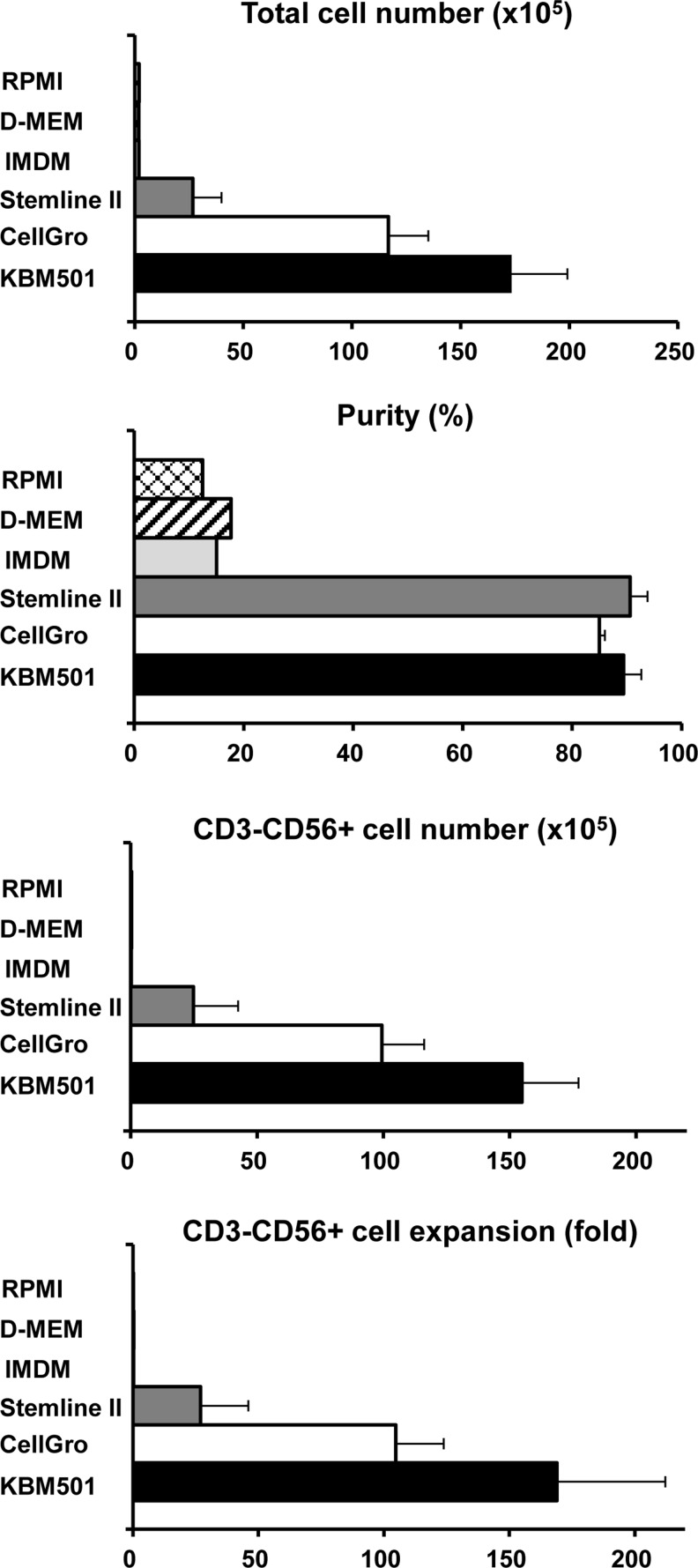

Next, we directly compared the effectiveness of several different culture media for purified NK cell production, based on a previous report in which CellGro SCGM was used in a typical NK production system (Sutlu et al., 2010). As shown in Fig. 2, the classical media (RPMI, DMEM, and IMDM) containing 2500 IU/mL of IL-2 and 5% heat-inactivated donor autoserum were not effective, and Stemline II, CellGro SCGM (2500 IU/mL of IL-2 and 5% heat-inactivated donor autoserum) and KBM501 (2813 IU/mL of IL-2 and 5% heat inactivated donor autoserum) showed good results. Although there was no statistical significance, KBM501 showed consistently better expansion data (mean=∼200-fold). We then examined the several concentrations of IL-2 (281, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 2813 IU/mL) for NK cell production. The dose-dependent efficiency of expansion was apparent, and KBM containing 2813 IU/mL of IL-2 consistently showed better expansion activity (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hgtb); therefore, the following experiments were done using KBM501 containing high IL-2 (2813 IU/mL).

FIG. 2.

Impact of culture medium on the production of NK cells from CD3-depleted PBMCs. An NK cell culture was established as shown in Fig. 3A using various culture media with high dose IL-2 (2500 IU/mL). Fourteen days later, the total cell number, purity, CD3-/CD56 NK cell yield, and fold expansion were assessed. Successful expansion was seen only when using Stemline II, CellGro SCGM, and KBM501, and the latter tended to show consistently better results.

Characteristics of Z-NK

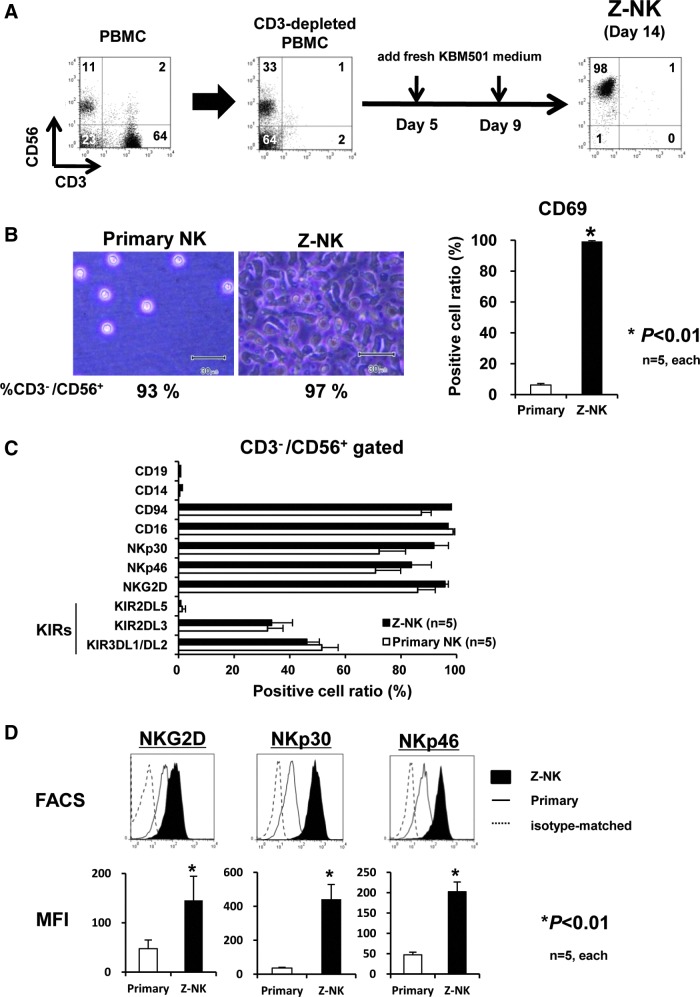

We fixed a simple 14-day culture period, because the cell number increased around 2 weeks of culture, and additional expansion was not observed under longer cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S2). The expanded and purified NK cells were designated Z-NK cells, as shown in Fig. 3A. The overall characteristics of Z-NK cells were evaluated by direct comparison with primary NK cells that were obtained as CD3−/CD56+ cells from fresh PBMCs.

FIG. 3.

Phenotype of zenithal-NK (Z-NK) cells. (A) Schematic diagram of feeder-free culture sequences for the production of Z-NK. (B) Microscopic morphology of primary NK and Z-NK at the end of 14 days of cultivation (left panels) and the expression of a typical activation inducer molecule, CD69 (right graph). (C) FACS analyses assessing the positive cell ratio of various surface markers (CD19, CD14, CD94, CD16, NKG2D), natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp30, NKp46), and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR2DL5, KIR2DL3, KIR3DL1/DL/2). (D) Quantitative expression level of some typical activation receptors (NKp30, NKp46, and NKG2D) assessed by mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hgtb

Two weeks after cultivation, Z-NK cells demonstrated a “green caterpillar-like” morphology (Fig. 3B, left panels), and almost all these cells expressed a typical activation inducer molecule, CD69 (Fig. 3B, right graph). In addition to the CD56, both primary NK and Z-NK cells extensively expressed typical surface markers of NK, CD94, and CD16, but not CD19 and CD14. The percentages of some typical activation receptors for NK cells (NKp30, NKp46, and NKG2D) and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR2DL5, KIR2DL3, and KIR3DL1/DL/2) were similar in both (Fig. 3C). The phenotypic characterizations of Z-NK and primary NK cells are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Very importantly, the expression levels of these activation markers of Z-NK were significantly higher than those seen in primary NK cells (Fig. 3D).

Cytolytic potential of Z-NK in vitro

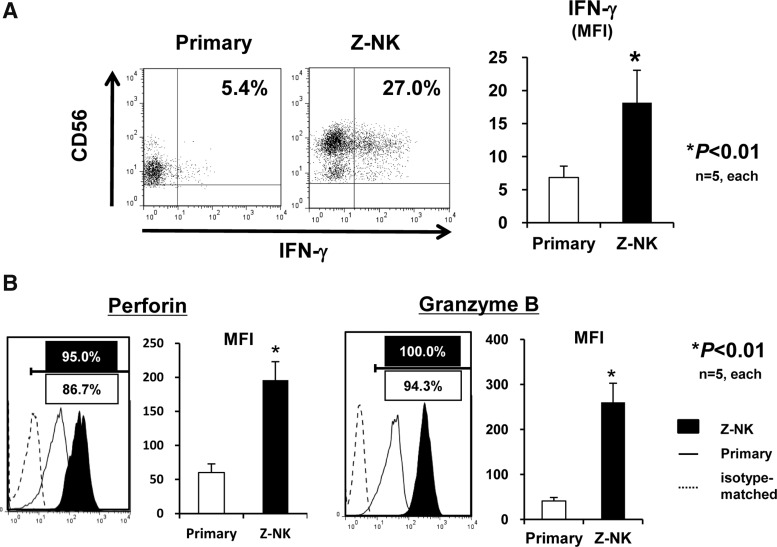

Next, we assessed the cytotoxic potential of Z-NK cells. Interestingly, the majority of primary NK cells were CD56dim cells, and after 14 days of cultivation, the majority of Z-NK cells were CD56high cells that expressed an increased amount of IFN-γ (Fig. 4A). In addition, the expression levels of typical cytolytic proteins of NK cells, perforin and granzyme B, were dramatically increased in Z-NK cells (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Antitumor potency of Z-NK cells. (A) Interferon (IFN)-γ expression of Z-NK and primary NK cells. Each line of NK cells was co-cultured with K562 target cells at a 2:1 effector-to-target ratio for 2 hr, and the expression of IFN-γ was assessed by intracellular FACS. Left panels show representative FACS profiles, and the right graph is the quantitative analysis based on MFI. Note that Z-NK cells contain a large CD56high population. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01. (B) Expression of perforin and granzyme B as assessed by intracellular FACS. The left panels show representative FACS profiles, and the right graphs show the results of the quantitative analyses. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01.

As the next step, the cytolytic potential of Z-NK was examined using a typical MHC class I-null cell line, K562. As shown in Fig. 5A, a dose-dependent response was apparent, and to our surprise, 2 hr of coculture with Z-NK cells was sufficient to kill nearly 100% of K562 (Fig. 5A, left graph). These data suggested that a one-to-one ratio of cell killing might be achieved through the use of Z-NK. A corresponding experiment confirmed the degranulation that was labeled by CD107a using these effector cells (Fig. 5A, right graph).

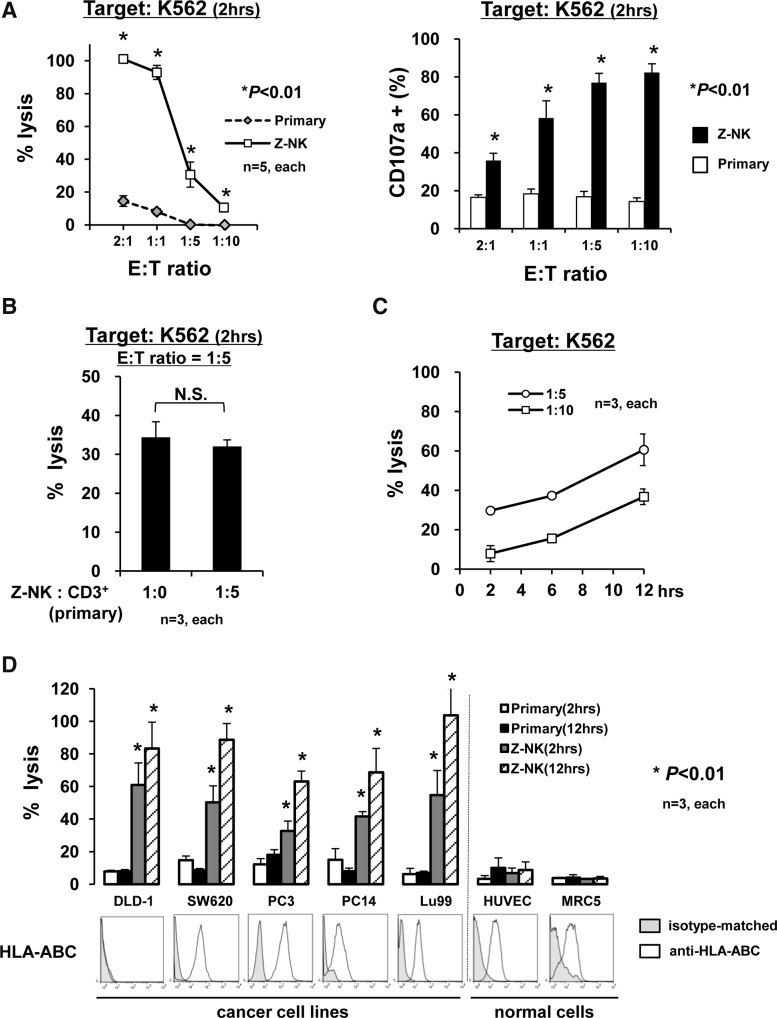

FIG. 5.

Antitumor activity of Z-NK cells. (A) Cytolytic activity of Z-NK and primary NK cells against K562. In the assay of NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity (left panel), nearly 100% cytotoxicity was achieved only after 2 hr at E:T=1:1. The corresponding NK cell degranulation, labeled by CD107a (right panel), was assessed by FACS analyses. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01. (B) The effect of primary CD3+ T cells on the cytotoxicity of Z-NK cells. After Z-NK cells were co-cultured with primary CD3+ T cells at a ratio of 1:5 for 16 hr, the number of NK cells in the cell culture was assessed by FACS and was taken as the number of effector cells. Then, NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed at a 1:5 effector-to-target ratio for 2 hr. The mean purity of primary T cells was ≥93%. No inhibitory effect of CD3+ T cells was evident. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01. (C) Time-dependent Z-NK–mediated cytotoxicity. The %lysis values against K562 at effector-to-target ratios of 1:5 and 1:10 were assessed at various time points (2, 6, and 12 hr). A time-dependent increase of cytolysis was apparent, suggesting that Z-NK cells mediated the killing of multiple cells. (D) Direct cytolysis of Z-NK cells against normal cells (human umbilical vein endothelial cells [HUVECs] and human embryonic lung fibroblast line [MRC5]) and various tumor cells with varied MHC class I expression patterns. NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed 2 or 12 hr later at E:T=1:1. Note that (1) no apparent cytolysis was found in normal cells; (2) incubation time-dependent cytolysis was seen when using Z-NK cells, not primary NK cells; and 3) the cytolysis could not be predicted by the expression patterns of HLA-ABC. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01.

Since CD3+ cells interfered with IL-2–dependent expansion and cell growth as shown in Fig. 1, we next assessed whether the coexistence of CD3+ cells might affect the cytolytic activity of Z-NK. As shown in Fig. 5B, the cytolytic activity of Z-NK cells was not affected at all at 16 hr after preinoculation with isolated CD3+ cells. This was a very important finding in terms of the clinical setting, because it suggested that, once activated, Z-NK cells would maintain their cytolytic activity in the blood circulation.

We next asked whether one Z-NK cell could kill one or more target cells. In experiments using a longer observation period, the %lysis values were found to be approximately ∼30% (E:T=1:5) and ∼10% (E:T=1:10) at 2 hr, and ∼60% (E:T=1:5) and ∼35% (E:T=1:10) at 12 hr (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that the killing of multiple cells could be expected from a single Z-NK cell.

Subsequently, the cytolytic activity of Z-NK against several human cancer cell lines (DLD-1, SW620, PC3, PC14, Lu99) as well as normal human cells (HUVECs and human fetus lung fibroblasts [MRC-5]) was examined. The MHC class I (HLA-ABC) expression of corresponding cells was also assessed. Of interest, Z-NK–mediated tumor cell killing was observed on tumor cells, irrespective of HLA-ABC expression, but not on normal cells (Fig. 5D).

The effect of cryopreservation on the viability and cell killing activity of Z-NK

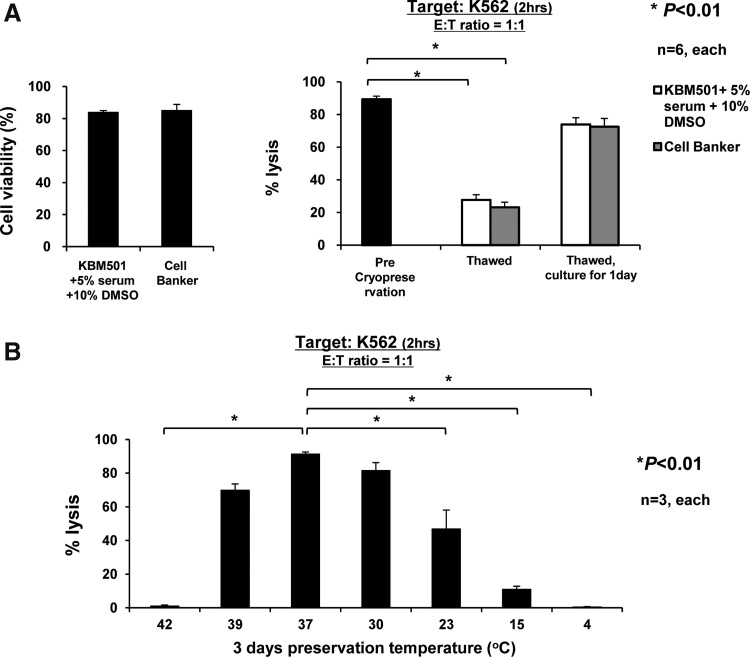

To examine whether it would be possible to use cryopreserved Z-NK cells, we next assessed the cell viability of cryopreserved and thawed Z-NK cells, and their cytolytic activity against K562 cells. The cell viability of thawed Z-NK cells was found to be approximately 74%–96%, indicating that cryopreservation itself might not seriously affect the viability of Z-NK cells (Fig. 6A, left panel). However, the cytolytic activity by thawed Z-NK was seriously impaired in comparison with that seen by pre-preserved Z-NK, which could be largely recovered by 1 day of culture under KBM501 (Fig. 6A, right panel). We determined that the preservation temperature was the critical factor affecting the killing activity of Z-NK cells, as shown in Fig. 6B.

FIG. 6.

Cytolytic function of Z-NK cells after cryopreservation and thawing and correlation with the preservation temperature. (A) The cell viability and cytolytic activity of thawed Z-NK cells. Z-NK cells were cryopreserved over 7 days, then thawed and analyzed in comparison with thawed cells cultured for 1 day in KBM501 with 5% human serum. The cell viability was assessed by trypan blue staining (left panel), and NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed 2 hr later at E:T=1:1 (right panel). The cryopreservation appeared not to have seriously affected the viability of Z-NK cells. However, the cytolytic activity of thawed Z-NK cells was seriously impaired in comparison with that seen by the pre-preserved Z-NK cells; the impaired activity could be largely recovered by 1 day of culture under KBM501. Results are shown as the means±SEM. (B) The effect of preservation temperature on cytolytic activity. Z-NK cells at the end of 14 days of cultivation were preserved for 3 days at various temperatures (4°C, 15°C, 23°C, 30°C, 37°C, 39°C, and 42°C). NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity was assessed 2 hr later at E:T=1:1. The preservation temperature was found to be a critical factor which dramatically affected the killing activity of Z-NK cells. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01.

Antitumor activity of Z-NK in vivo

Finally, we assessed the antitumor activity of Z-NK cells in vivo using a dermal tumor composed of K562 cells on NOD/SCID mice (Castriconi et al., 2007). Four days after tumor cell inoculation into the abdominal wall, when the tumor was established as ∼3 mm, primary NK (1×106) or Z-NK (5×105 or 1×106) cells were administered intravenously via a tail vein. As shown in Fig. 7A and 7B, bolus injection of Z-NK, but not primary NK, significantly prevented tumor formation, and a dose-response was also apparent. Complete elimination of the established tumor was seen in two of seven mice (28.6%) treated with Z-NK cells (1×106). Significant prolongation of the survival of animals was also observed in animals receiving 1×106 Z-NK cells (Fig. 7C). Then, to determine whether or not Z-NK was recruited into the xenografted tumors, we performed an immunohistochemical analysis. The recruitment of the adaptively transferred human NK cells into the xenografted tumors was observed in mice treated with primary NK (1×106; mean: 4.7 cells/mm2; range: 0–8 cells/mm2) and Z-NK cells (1×106; mean: 14.7 cells/mm2; range: 5–33 cells/mm2; Supplementary Fig. S3). Systemic autopsy examination of these mice revealed neither an apparent inflammatory reaction nor tissue damage in any vital organs (data not shown). Moreover, similar antitumor effects were observed on some of the established human tumors tested in Fig. 5D (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Antitumor effect of Z-NK cells in vivo. The antitumor effects of primary NK and Z-NK cells were assessed by using a mouse tumor xenograft model. Four days after tumor cell inoculation on the abdominal wall of NOD/SCID mice, when the tumor was established as ∼3 mm in diameter, NK or Z-NK cells were administered by bolus injection via a tail vein. The data show the results of two independent experiments. (A) Typical and representative gross observation of mice with K562 tumors treated with or without primary NK or Z-NK cells 19 days after tumor cell inoculation. Note the dramatic inhibition of tumor growth in mice treated with 1×106 Z-NK cells by bolus injection. (B) Time course of the tumor volume treated. Results are shown as the means±SEM. *p<0.01. (C) Survival Kaplan–Meier curve. Note that the bolus injection of 1×106 Z-NK cells significantly delayed the death of the animals, and two of seven animals showed complete remission of the tumors and long-term survival. The data were analyzed by log-rank test. *p<0.01.

These results strongly suggest that Z-NK would be safe and beneficial for tumor-bearing individuals in a clinical setting.

Discussion

We here determined several important parameters for the establishment of a simple ex vivo manipulation method for Z-NK cells, a novel line of highly activated and purified human NK cells. The key observations obtained in this study were as follows: (1) CD3 depletion from PBMCs, high-dose IL-2, and use of a specific culture medium were sufficient to produce Z-NK cells; (2) increased expression of CD69 and some typical activation receptors (NKp30, NKp46, and NKG2D), IFN-γ, and cytotoxic molecules (perforin and granzyme B) and nearly 100% of target cell killing activity were observed under only 2-hr incubation and an E:T ratio of 1:1; (3) Z-NK cells could efficiently kill multiple human tumor cells, but not normal cells, irrespective of the expression levels of MHC class I molecules; and (4) the strong cytolytic activity of Z-NK cells was maintained in an in vivo NOD/SCID tumor model. These findings indicate that the Z-NK cells established here may be under a near optimally activated state that has never been achieved by preexisting techniques, and thus the Z-NK cell line may contribute to the advance of tumor adoptive immunotherapy in a clinical setting.

Although the establishment of NK cell–based adoptive immunotherapy has long been sought as a hopeful alternative to treat advanced malignancies (Sutlu and Alici, 2009), its development has been much delayed because of technical difficulties in the production of appropriate NK cells of a sufficient amount, purity, and activation for therapeutic requirements. The current status involves very few clinical trials, and thus there has been very sparse information with respect to (1) whether high yield, high purity, or high activation should be prioritized (Berg and Childs, 2010) and (2) identification of an acceptable therapeutic regimen with good clinical outcome, including doses, intervals, and administration route.

A number of pioneering investigators have made concerted efforts to produce potentially therapeutic NK cells under good manufacturing practice conditions (Koehl et al., 2005; Berg et al., 2009; Sutlu et al., 2010).

First, Koehl et al. (2005) reported the use of a feeder-free method to generate expanded (mean: 5-fold) and highly purified (>95%) human NK cells from magnetic bead–selected primary CD3−/CD56+ cells. For clinical use, however, a method was needed to produce activated NK cells in high yield to assess the efficacy of treatment. Next, an impressive report using a feeder-free large-scale bioreactor system yielded expanded (>1000-fold) and enriched NK cells (mean: 38%; range: 10–80%), reaching a yield of 9.8×109 NK cells (average) but also producing a considerable amount of T cells and NK T cells (Sutlu et al., 2010). Again, however, clinical use required highly pure NK cells (ideally, NK cells with a consistent purity of >90%) to assess the safety and/or efficacy of the treatment, and particularly when using allogeneic NK cells in order to avoid graft-versus-host diseases (Berg and Childs, 2010). As an alternative, Berg et al. reported the use of a third party irradiated allogeneic EBV-LCL feeder line to generate expanded (mean: 184-fold) and highly purified (mean: 99%; range: 96%–100%) human NK cells from magnetic bead–selected primary CD3−/CD56+ cells (Berg et al., 2009; Berg and Childs, 2010). The simplified feeder-free method demonstrated in this study showed a similar expansion ratio (mean: 197-fold) and a little less purity (mean: 90%; range: 76%–98%) of Z-NK cells, with a small T-cell subset of several percent (Fig. 1D). These comparisons suggest that the EBV-LCL feeder+X-VIVO20 medium in Berg's culture system (Berg et al., 2009) could be replaced with medium containing CD3-depleted crude PBMCs without a third party feeder line+KBM501. When considering allogeneic Z-NK administration, in turn, it may be necessary to add T-cell depletion and/or CD56 selection; however, this may be not be terribly important, because it has been reported that a number of T cells lose their alloreactive potential after more than 7 days of culture (Carlens et al., 2002; Speiser and Romero, 2005; Gattinoni et al., 2005; Matter et al., 2007). In the context of autologous infusion, Z-NK cells may be advantageous because of their simple cultivation process.

We must emphasize that the cellular phenotype and activity of Z-NK cells would suggest their near-fully activated state, and some of the data obtained here are similar in some regard to those by Berg et al. (2009), who used EBV-LCL feeder cells. For example, the cytolytic activities against K562 cells at an E:T ratio of 1:1 were 70%–75% (5 hr, Berg-NK) in the study by Berg et al. (2009) versus 96%–100% (2 hr, Z-NK) in the present work, and both these cytolytic activities appeared to be stronger than those reported by Koehl et al. (2005) (4 hr; mean: 25%) and Sutlu et al. (2010) (4 hr; mean: 35%). Together, these results suggest that the stimulation of an allogeneic third party feeder may not always be required to generate highly activated NK cells during the expansion process, when appropriate cell components, media, and IL-2 concentrations are employed.

A possible key issue that may be encountered in a clinical setting is the “loss of function” of Z-NK cells, such as observed in the case of CD8+ T cells (Carlens et al., 2002; Speiser and Romero, 2005; Gattinoni et al., 2005; Matter et al., 2007), when administered to patients with advanced malignancy. This may possibly occur via KIRs, especially in the case of autologous NK-based adoptive immunotherapy. As preclinical data, we here performed experiments to examine the effect of a mixture of CD3+ cells (Fig. 5B) and the therapeutic potential of Z-NK cells in vivo using a tumor-bearing mouse model (Fig. 7). Neither experiment supported the possibility of loss of the antitumor activity of Z-NK; however, this possibility (Suck and Koh, 2010) should be assessed in future clinical trials.

In addition, as shown in Fig. 7, the dose of Z-NK would be a key parameter affecting the therapeutic efficacy, at least in dermal tumors. Establishment of a more efficient expandable technique or, alternatively, strategies to enhance the antitumor effect of Z-NK, including antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, may be required in the near future. Therefore, further studies assessing improvements to the current cell processing system as well as clinical evaluation of the dose-limiting toxicity and therapeutic efficacy should be continued.

In summary, we here established a simple feeder-free culture method to obtain from PBMCs a near-fully activated line of human NK cells, which we designated Z-NK cells. The data obtained in this study strongly support the idea that the Z-NK cell line warrants further investigation for its potential to treat advanced malignancies in a clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Chie Arimatsu, Mrs. Aki Furuya, and Mrs. Ryoko Nakamura for their assistance with the animal experiments. KN International, Ltd. assisted in the revision of the language in this manuscript. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to YY), and by a grant from tella Inc. (to YY).

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Yonemitsu is a member of the Board of Directors of tella Inc. None of the authors has any conflict of interest to report.

References

- Aparicio-Pagés M.N. Verspaget H.W. Peña A.S. Lamers C.B. Natural killer cell activity in patients with adenocarcinoma in the upper gastrointestinal tract. J. Clin. Lab. Immunol. 1991;35:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S. Meagher R. Swearingen M., et al. Infusion of the allogeneic cell line NK-92 in patients with advanced renal cell cancer or melanoma: a phase I trial. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:625–632. doi: 10.1080/14653240802301872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M. Childs R. Ex-vivo expansion of NK cells: What is the priority - high yield or high purity? Cytotherapy. 2010;12:969–970. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.536216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M. Lundqvist A. McCoy P., Jr., et al. Clinical-grade ex vivo-expanded human natural killer cells up-regulate activating receptors and death receptor ligands and have enhanced cytolytic activity against tumor cells. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:341–355. doi: 10.1080/14653240902807034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biassoni R. Cantoni C. Marras D., et al. Human natural killer cell receptors: insights into their molecular function and structure. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2003;7:376–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittenden J. Heys S.D. Ross J. Eremin O. Natural killer cells and cancer. Cancer. 1996;77:1226–1243. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1226::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri M.A. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlens S. Liu D. Ringden O., et al. Cytolytic T cell reactivity to Epstein-Barr virus is lost during in vitro T cell expansion. J. Hematother. Stem. Cell. Res. 2002;11:669–674. doi: 10.1089/15258160260194811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castriconi R. Dondero A. Cilli M., et al. Human NK cell infusions prolong survival of metastatic human neuroblastoma-bearing NOD/scid mice. Cancer. Immunol. Immunother. 2007;56:1733–1742. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang W.L. Liu H.W. Chang W.Y. Natural killer cell activity in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma relative to early development and tumor invasion. Cancer. 1990;65:926–930. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900215)65:4<926::aid-cncr2820650418>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud A.G. Caligiuri M.A. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol. Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L. Klebanoff C.A. Palmer D.C., et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI24480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller M.A. Cooley S. Judson P.L., et al. A phase II study of allogeneic natural killer cell therapy to treat patients with recurrent ovarian and breast cancer. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:98–107. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.515582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F.M. Vargas J.A. Lopez-Cortijo C., et al. Prognostic significance of natural killer cell activity in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck. Surg. 1998;124:852–856. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.8.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm E.A. Mazumder A. Zhang H.Z. Rosenberg S.A. Lymphokine-activated killer cell phenomenon. Lysis of natural killer-resistant fresh solid tumor cells by interleukin 2-activated autologous human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1982;155:1823–1841. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.6.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karre K. NK cells, MHC class I molecules and the missing self. Scand. J. Immunol. 2002;55:221–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi A. Takamori Y. Ogawa K., et al. Differential expression of granulysin and perforin by NK cells in cancer patients and correlation of impaired granulysin expression with progression of cancer. Cancer. Immunol. Immunother. 2002;50:604–614. doi: 10.1007/s002620100228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl U. Sörensen J. Esser R., et al. IL-2 activated NK cell immunotherapy of three children after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Blood. Cells. Mol. Dis. 2004;33:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl U. Esser R. Zimmermann S., et al. Ex vivo expansion of highly purified NK cells for immunotherapy after haploidentical stem cell transplantation in children. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217:345–350. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-872520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaru A. Ueda Y. Furuya A., et al. Sustained and NK/CD4+T cell-dependent efficient prevention of lung metastasis induced by dendritic cells harboring recombinant Sendai virus. J. Immunol. 2009;183:4211–4219. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo E. Koda K. Takiguchi N., et al. Preoperative natural killer cell activity as a prognostic factor for distant metastasis following surgery for colon cancer. Dig. Surg. 2003;20:445–451. doi: 10.1159/000072714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahat N. Alexander B. Levin D.R. Moskovitz B. The relationship between clinical stage, natural killer activity and related immunological parameters in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer. Immunol. Immunother. 1989;28:208–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00204990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law T.M. Motzer R.J. Mazumdar M., et al. Phase III randomized trial of interleukin-2 with or without lymphokine-activated killer cells in the treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:824–832. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950901)76:5<824::aid-cncr2820760517>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W. Iyengar R. Leimig T., et al. Phenotype and function of human natural killer cells purified by using a clinical-scale immunomagnetic method. Cancer. Immunol. Immunother. 2005;54:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0609-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljunggren H.G. Karre K. In search of the missing self: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Immunol. Today. 1990;11:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter M. Pavelic V. Pinschewer D.D., et al. Decreased tumor surveillance after adoptive T-cell therapy. Cancer. Res. 2007;67:7467–7476. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K. Dimasi N. Wang J., et al. Structure and function of natural killer cell receptors: multiple molecular solutions to self, nonself discrimination. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:853–885. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S. Lymphokine-activated killer cells: a new approach to immunotherapy of cancer. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 1985;75:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S.A. Lotze M.T. Yang J.C., et al. Prospective randomized trial of high-dose interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with lymphokine-activated killer cells for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 1993;85:622–632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.8.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubnitz J.E. Inaba H. Ribeiro R.C., et al. NKAML: a pilot study to determine the safety and feasibility of haploidentical natural killer cell transplantation in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:955–959. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri L. Capanni M. Urbani E. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser D.E. Romero P. Toward improved immunocompetence of adoptively transferred CD8+T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1467–1469. doi: 10.1172/JCI25427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suck G. Koh M.B. Emerging natural killer cell immunotherapies: large-scale ex vivo production of highly potent anticancer effectors. Hematol. Oncol. Stem. Cell. Ther. 2010;3:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s1658-3876(10)50024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suck G. Oei V.Y. Linn Y.C., et al. Interleukin-15 supports generation of highly potent clinical-grade natural killer cells in long-term cultures for targeting hematological malignancies. Exp. Hematol. 2011;39:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutlu T. Alici E. Natural killer cell-based immunotherapy in cancer: current insights and future prospects. J. Intern. Med. 2009;266:154–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutlu T. Stellan B. Gilljam M., et al. Clinical-grade, large-scale, feeder-free expansion of highly active human natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy using an automated bioreactor. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:1044–1055. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.504770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.