Background: Double-stranded RNA-binding domain-containing proteins play key roles in microRNA biogenesis.

Results: The Microprocessor protein DGCR8 binds RNA targets nonspecifically.

Conclusion: DGCR8 alone is not responsible for specific RNA target recognition by the Microprocessor.

Significance: Faithful RNA processing is not causatively coupled to specific substrate binding properties of DGCR8.

Keywords: MicroRNA, NMR, Protein-Nucleic Acid Interaction, RNA-binding Protein, RNA Structure, DGCR8, Drosha, Microprocessor, Double-stranded RNA-binding Domain (dsRBD)

Abstract

MicroRNA (miRNA) biogenesis follows a conserved succession of processing steps, beginning with the recognition and liberation of an miRNA-containing precursor miRNA hairpin from a large primary miRNA transcript (pri-miRNA) by the Microprocessor, which consists of the nuclear RNase III Drosha and the double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein DGCR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region protein 8). Current models suggest that specific recognition is driven by DGCR8 detection of single-stranded elements of the pri-miRNA stem-loop followed by Drosha recruitment and pri-miRNA cleavage. Because countless RNA transcripts feature single-stranded-dsRNA junctions and DGCR8 can bind hundreds of mRNAs, we explored correlations between RNA binding properties of DGCR8 and specific pri-miRNA substrate processing. We found that DGCR8 bound single-stranded, double-stranded, and random hairpin transcripts with similar affinity. Further investigation of DGCR8/pri-mir-16 interactions by NMR detected intermediate exchange regimes over a wide range of stoichiometric ratios. Diffusion analysis of DGCR8/pri-mir-16 interactions by pulsed field gradient NMR lent further support to dynamic complex formation involving free components in exchange with complexes of varying stoichiometry, although in vitro processing assays showed exclusive cleavage of pri-mir-16 variants bearing single-stranded flanking regions. Our results indicate that DGCR8 binds RNA nonspecifically. Therefore, a sequential model of DGCR8 recognition followed by Drosha recruitment is unlikely. Known RNA substrate requirements are broad and include 70-nucleotide hairpins with unpaired flanking regions. Thus, specific RNA processing is likely facilitated by preformed DGCR8-Drosha heterodimers that can discriminate between authentic substrates and other hairpins.

Introduction

miRNAs2 are a conserved class of ∼22-nucleotide (nt) noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by base pairing with target mRNA sequences. They play key roles in modulating cellular and developmental processes (1, 2) and have been implicated in a broad range of metabolic, immunological, psychiatric, and cell cycle disorders (3–6). Mature miRNAs are generated through a conserved succession of processing steps. Typically, miRNA biogenesis begins in the nucleus with the generation of a long pri-miRNA transcript by RNA polymerase II. A hairpin harboring the pri-miRNA is selected for processing by the nuclear RNase III Drosha, which liberates the miRNA-containing pre-miRNA. Exportin-5 transports the pre-miRNA to the cytoplasm where it undergoes a second round of processing (7, 8). Another RNase III, Dicer, trims the terminal loop to generate a 21–24-nt RNA duplex bearing 2-nt 3′ overhangs (9).

Processing of pri- and pre-miRNAs by members of the RNase III family is facilitated by accessory proteins comprising multiple dsRBDs featuring characteristic α-β-β-β-α motifs. In humans, DGCR8 is required for Drosha processing and contains tandem dsRBDs (10). DGCR8 interacts with ferric heme as a cofactor to increase processing activity (11–13), and although the cooperative formation of oligomeric DGCR8/pri-miRNA assemblies has been described as another positive modulator of pri-miRNA processing (14), lysine acetylation within the tandem dsRBDs decreases the affinity of DGCR8 for pri-miRNA thereby down-regulating processing (15).

Two modes of pri-miRNA recognition have been presented. In one model, the Microprocessor binds a large (>10-nt) terminal loop to position Drosha's catalytic center roughly two helical turns (∼22-nt) from the stem-loop junction, resulting in the liberation of the ∼70-nt pre-miRNA (16). A more recent model suggests that the terminal loop is dispensable for Microprocessor recognition. Instead, DGCR8 recognizes the hairpin's basal ss-dsRNA junction and recruits Drosha for cleavage (17). However, the generality of this model is unclear because further experiments revealed that the length and symmetry of 5′- and 3′-nonstructured ssRNAs required for efficient processing are variable and pri-miRNA-dependent (18). Most Caenorhabditis elegans pri-miRNAs apparently lack determinants required for processing in human cells, yet one-fifth of all human pri-miRNAs lack primary sequence determinants such as downstream SRp20 binding, basal UG, and the apical GUG motifs, recently described by Bartel and co-workers (19). Collectively, this leaves 70-nt hairpins with unpaired flanking regions as the only feature and common denominator across Microprocessor substrates.

Although most dsRBDs have been reported to bind duplex RNA as the name implies, unpaired ssRNA in loops, bulges, and mismatched pairs can also be recognized (20–23). This flexibility in substrate recognition presents a challenge in identifying both protein and RNA features required for specific protein-RNA interaction in the absence of structural data. A recent genome-wide view of DGCR8 function employing RNA cross-linking immunoprecipitation sequencing studies revealed a much broader RNA target base than anticipated (24). Specifically, these results showed that DGCR8 targets hundreds of mRNAs in addition to the anticipated interactions with pri-miRNA substrates. Implications for DGCR8 function ranged from roles in small nucleolar RNA and long noncoding RNA stabilization to regulation of alternatively spliced isoforms.

In this study, we investigated the RNA binding properties of the integral Microprocessor component DGCR8. Along with ssRNA and perfectly paired dsRNA substrates, we designed a comprehensive series of pri-mir-16-1 variants to elucidate the role of RNA secondary structure elements in DGCR8-RNA in general as well as the initiating event of pri- to pre-miRNA processing. These mutants were also used to investigate the link between recognition and processing of pri-miRNA substrates. Because detailed structural information on DGCR8·pri-miRNA complexes remains elusive, we utilized NMR spectroscopy to elucidate the interaction at single residue resolution and diffusion measurements to probe complex formation in solution. Although DGCR8 in isolation did not discriminate between the broad array of RNAs tested, functional processing assays confirm the specificity of Microprocessor assemblies. Thus, our results point to an intricate relationship between DGCR8 and Drosha in which both proteins are required for binding and processing, rather than a hierarchical DGCR8-mediated pri-miRNA recognition and subsequent Drosha recruitment model.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

RNA Transcription and Purification

Pri-miRNA-containing plasmids were purified with the Omega Plasmid Giga kit, linearized with the appropriate 3′ restriction endonuclease, phenol/chloroform-extracted, and ethanol-precipitated. The minimal pri-mir-16-1 construct includes 18 nt upstream of the 5′- and 16 nt downstream of the 3′-cleavage site. Although two additional Gs were added to the 5′ overhang for efficient transcription, an additional AUUU sequence was added to the 3′ overhang after linearization employing SwaI (New England Biolabs). In vitro reactions were performed in transcription buffer (40 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mm spermidine, 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.01% Triton X-100) containing 0.05 μg/ml plasmid template, 30 mm MgCl2, 1 μm T7 RNA polymerase and 6.5 mm each ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP. Transcription reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h.

Transcripts were purified as described previously (25). Briefly, the RNA was exchanged to buffer containing 10 mm NaPO4, pH 6.5, 25 mm KCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 25 μm NaN3. Full-length transcripts were separated from the protein, unincorporated nucleotides, and abortive transcripts by anion exchange chromatography (GE HiTrapQ HP).

Protein Expression and Purification

N-terminal, tobacco etch virus protease-cleavable His6-GB1/DGCR8Δ275, DGCR8PC, DGCR8core, and DGCR8RBD1 (residues 509–582) sequences were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL competent cells, and expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thio-galactoside for 2–4 h at 37 °C (DGCR8Δ275 cultures were supplemented with 1 mm δ-aminolevulinic acid) (13) and purified with a HisTrapFF affinity column per the manufacturer's instructions. Partially purified fusion proteins were cleaved with tobacco etch virus protease overnight at room temperature and reapplied to the HisTrap column. The purified protein was then exchanged into buffer appropriate for NMR analysis or biochemical assays using a PD-10 desalting column. Cultures of E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells expressing DGCR8core and DGCR8RBD1 (residues 509–582) were grown from a single colony in 2 ml of LB/Amp100 at 37 °C overnight. These cultures were then adapted to growth in 500 ml of 100% D2O-15N,13C-enriched M9 minimal media (26) with a succession of small volume cultures grown at 37 °C with 200 rpm agitation. Expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl β-d-thio-galactoside for 4 h at 37 °C and purified as described previously (27). Identical batches of DGCR8 protein variants were used in successive binding and processing assays.

Microfiltration Double-filter Binding Assays

Filter binding was performed essentially as described in Arraiano et al. (28). Briefly, in vitro transcribed, purified RNA was end-labeled with γ-32P and then re-purified by urea-PAGE and gel extraction. The labeled RNA stocks were quantified and diluted to 30 μm. [32P]RNA was diluted to 200 pm (2× stock) with microfiltration buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT). The RNA was annealed by incubating at 65 °C for 5 min and then ice for 3 min. Purified protein for filter binding was prepared as 2× stocks by serial dilution in 1× microfiltration buffer. Equal volumes of 2× RNA and protein stocks were combined to yield 50-μl binding reactions. The reactions were incubated at room temperature for 1 h.

The binding reactions were filtered through nitrocellulose and nylon membranes sequentially using the BioDot microfiltration apparatus. Sample wells were washed with 2× 100 μl of microfiltration buffer before and after sample loading. Membranes were air-dried, and the intensity of the spots was quantified by a phosphorimager. The data were fit using a nonlinear least sum of squares analysis with Equation 1,

|

where FB is the fraction of RNA bound to protein; FBmin is the minimum fitted value of FB; FBmax is the maximum fitted value of FB; [DGCR8] is the molar concentration of protein, and n is the fitted value of the slope of the curve.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Purified pri-miRNA transcripts were γ-32P-end-labeled and purified as described previously (29). A 20× pri-miRNA stock was heated to 65 °C for 5 min and annealed on ice for 3 min. DGCR8 variants were diluted to the appropriate concentration as 20× stocks with EMSA reaction buffer. EMSA samples were prepared in 20 μl in reaction buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.2 nm pri-miRNA. Reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and resolved on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE.

RNA Secondary Structure Determination by NMR

All NMR spectra were recorded at 288 K or 298 K on Bruker Avance 800 or 850 MHz spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe. NMR experiments were performed on samples of 500-μl volume containing 0.1–1.6 mm of pri-mir-16 RNA variants. Data were processed using nmrPipe (30) and analyzed using Sparky (31). One-dimensional imino proton spectra were acquired using a jump-return echo sequence (32). Imino proton resonances were assigned sequence-specifically from water flip-back two-dimensional NOESY spectra (τmix = 200 ms) (33). Assignments were confirmed using a jump-return (32) 15N-HMQC (34). Elucidation of base pairing and secondary structure was verified from the 2JNN coupling through hydrogen bonds in the TROSY-based HNN-COSY data (35, 36).

The pri-mir-16lower RNA tertiary structure was predicted using the MC-sym software (37). All information required to generate and edit the scripts are found on line on the MC-pipeline website. Briefly, all-atom models for the 65-nucleotide pri-mir-16lower satisfying the NMR-derived secondary structure were generated. 132 structures were clustered using MC-Sym, and five representative structures were selected. AMBER energy minimization was employed to refine the final five atomistic three-dimensional structures as implemented in MC-sym.

DGCR8 NMR Analysis

Backbone 1HN, 15N, 13CO, 13Cα, and 13Cβ chemical shift assignments for DGCR8core have been obtained using a strategy based on three-dimensional triple resonance experiments employing transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY), and chemical shifts have been deposited in the BioMagResBank under accession number 17773 (27). Standard three-dimensional NMR techniques (38) were employed to obtain and confirm backbone assignments for DGCR8RBD1 (residues 509–582) (39). Line width and cross-peak intensities of 1H,15N-TROSY experiments at varying protein/RNA ratios were determined using Sparky, assuming Gaussian line shapes (31).

DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower Titration

2H,15N-DGCR8core and pri-mir-16lower were buffer-exchanged to NMR buffer (20 mm NaPO4, pH 7.0, 150 mm KCl, 5 mm DTT) with the PD-10 desalting column. Titrations were performed by the addition of diluted RNA to protein in NMR buffer. Samples were concentrated with the Amicon concentrator (10K MWCO) in 500 μl of 90% H2O, 10% 2H2O. RNA was added to 250 μm DGCR8core to reach protein/RNA molar ratios of 48:1, 24:1, 12:1, 6:1, 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2. Alternatively, diluted DGCR8core was added to 250 μm pri-mir-16lower to reach RNA/protein molar ratios of 48:1, 24:1, 12:1, 6:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively. Titrations were performed in NMR buffer in the absence and presence of 5 mm MgCl2.

Measurement of DGCR8-pri-miRNA Diffusion Constants by PFG NMR

All PFG-NMR experiments were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer operating at 600 MHz and equipped with a 5-mm QXI quadruple resonance (1H,19F-13C,31P) room temperature probe with triple-axis shielded gradients. The bipolar pulse pair longitudinal eddy current delay (BPPLED) sequence (40, 41) was used, and one-dimensional spectra were recorded after two-axis gradient encoding and decoding separated by a diffusion delay of 100 ms. Dephasing of the NMR signal in the BPPLED experiment was analyzed according to Equation 2 (40, 42),

|

where A(g) is the measured intensity of the NMR signal as a function of the fractional gradient strength g; A(g0) is the peak intensity of the reference spectrum (g0 = 2%); D is the translational diffusion constant; γH is the gyromagnetic ratio of a proton (2.675197 × 104 G−1·s−1); δ is the gradient duration; Gmax is the combined maximum power (87.8 G·cm−1 at g = 100%) offered by the x and z gradients; Δ is the time between gradients, and τ the recovery time. By taking the natural logarithms of both sides of Equation 2, a linear equation results, and D can be calculated from least squares linear fits. To exclude complications with any exchangeable protons, the diffusion analysis of deuterated protein samples was performed by integrating over the 0.35–1.05 ppm section of the methyl region of the spectrum (primarily CH2D and CHD2 isotopomers). RNA samples were analyzed by integrating over the 7.3–8.0 ppm section.

The diffusion rate of a molecule depends on its size and shape, its concentration, the temperature, and solvent viscosity. The Stokes-Einstein equation shows that a sphere's diffusion coefficient (D) is inversely related to the hydrodynamic radius (RH) and solvent viscosity (η) as shown in Equation 3,

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature (298 K).

Obtaining the hydrodynamic radius RH for a spherical particle using Equation 3 requires an accurate measure of the solvent viscosity η. All samples were dissolved in identical aqueous (90:10% H2O/D2O) buffer solutions containing 150 mm KCl. Using viscosities of 1.097 and 0.8929 kg·cm−1·s−1 for a 100% D2O and a 100% H2O solution (43), the viscosity of a mixture of light and heavy water can be represented by a linear function of concentration (44) shown in Equation 4,

which yields 0.91331 kg cm−1 s−1 at 298 K. A salt effect correction on viscosity was performed according to the Jones-Dole Equation 5 (45),

|

where c is the molar salt concentration; η0 is the uncorrected and η = 0.9018 kg cm−1 s−1 the corrected solvent viscosity with A = 0.0057 and B = −0.0147 for KCl (46).

Fractional populations of monomer and dimer states can be estimated using Equation 6,

where DM and DD are the respective diffusion coefficients for monomer and dimer and fD is the molar fraction of the dimeric species.

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

SEC characterization of 150 μm DGCR8core was performed in NMR buffer (20 mm NaPO4, pH 7.0, 150 mm KCl, 5 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) at 12 °C with a Superdex75 10/300 column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Conalbumin, ovalbumin, carbonic anhydrase, GB1, and aprotinin were used to generate the standard curve from which the apparent DGCR8core molecular weight was estimated.

pri-miRNA Processing Employing an Immunoprecipitated Microprocessor

In vitro processing assays were performed essentially as described by Lee and Kim (29) with the following modifications: c-Myc-Drosha and FLAG/HA-DGCR8 (47) were co-transfected (Lipofectamine, Invitrogen) in the mammalian cell line AD-293 (Stratagene), and Drosha/DGCR8 was co-immunoprecipitated with either EZview anti-c-Myc affinity gel (Sigma) or agarose-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Immunoprecipitated Microprocessor was incubated with 32P-pri-miRNA, in the presence of Mg2+ and RNaseOUT (Invitrogen) for 90 min at 37 °C. RNA was purified by phenol/chloroform and resolved on a 12% denaturing PAGE. Gels were dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

For Microprocessor reconstitution assays, the Drosha immunoprecipitate was washed with a basic, high salt buffer to remove co-purified proteins. Stringent washes were performed with 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 2.5 m NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% deoxycholic acid, and 1 m urea. A final wash with 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl was performed. For the processing assays, c-Myc-Drosha was preincubated with recombinant DGCR8Δ275 in the presence of Mg2+ and RNase OUT (Invitrogen) for 10 min at room temperature. After addition of [32P]RNA, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. RNA was purified, and samples were processed as described above.

DGCR8 and Drosha Co-immunoprecipitation

Whole cell extracts of AD293 mock-transfected or transfected with c-Myc-Drosha/FLAG-DGCR8 were obtained as described above. Supernatant from lysed cells was incubated with either RNase inhibitor or RNase A/T1 mix (Ambion). After incubation for 60 min at 4 °C, EZ view c-Myc beads (Sigma) were added and incubation proceeded for another 16 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed with lysis buffer and resuspended in SDS-loading buffer. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed with anti-c-Myc or anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma).

RESULTS

pri-miRNA Recognition by DGCR8

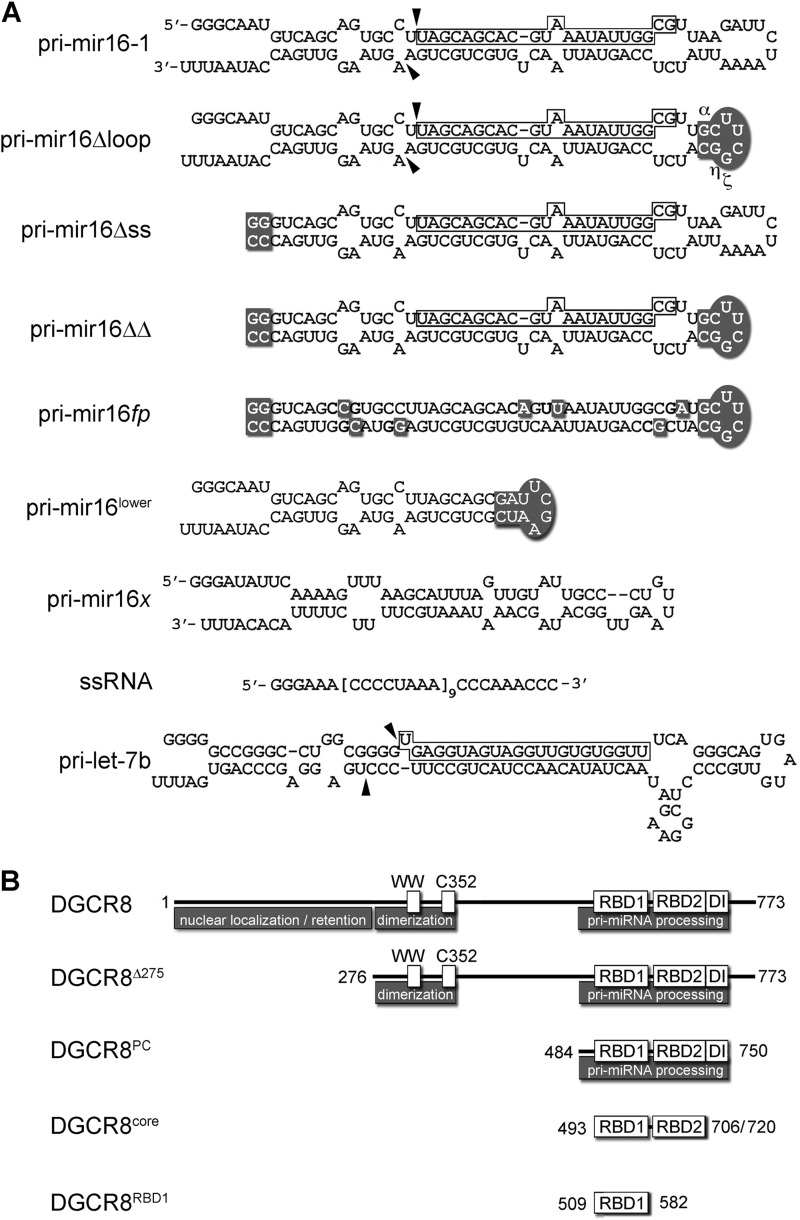

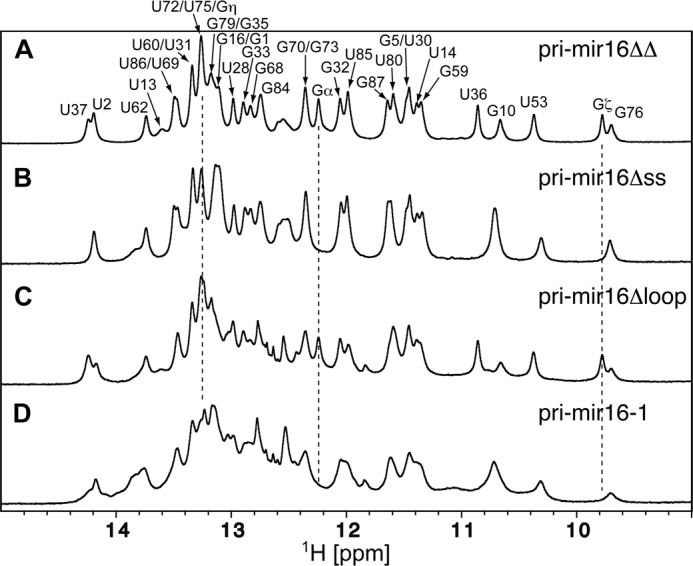

To investigate the secondary structure elements required for pri-miRNA recognition by DGCR8, we performed quantitative binding studies using a series of pri-mir-16-1 variants. Along with the 104-nt hairpin that includes single-stranded regions at both the base and terminal loop, we generated a terminal loop mutant (pri-mir-16Δloop) by replacing 14 nucleotides of the loop with a G:C-C:G clamp and UUCG tetraloop. We also created a pri-mir-16 mutant lacking single-stranded 5′ and 3′ overhangs (pri-mir-16Δss) and a pri-mir-16ΔΔ mutant that incorporates both modifications (Fig. 1A). Each pri-miRNA secondary structure was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy monitoring imino proton resonances (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Constructs used in DGCR8/pri-miRNA experiments. A, Mfold (73)-predicted secondary structures of in vitro transcripts. Dark boxes represent sequence mutations; arrows indicate Drosha cleavage sites, and open boxes highlight mature miRNA sequences. The ssRNA construct is an unstructured 87-nt transcript containing nine repeats of the bracketed sequence. pri-mir-16x is an Mfold-predicted 82-nt hairpin located 397 nt upstream of pri-mir-16-1. B, full-length and truncated DGCR8 constructs are shown in the context of functionally significant domains. WW refers to the proline-binding WW domain; C352 is a cysteine required for heme coordination; RBDs are RNA-binding motifs, and DI refers to the Drosha-interaction/trimerization domain.

FIGURE 2.

NMR-based secondary structure confirmation of pri-mir-16-1 variants. 800 MHz imino one-dimensional jump-return echo experiments were collected at 298 K. A, pri-mir-16ΔΔ RNA. The spectrum is labeled with assignment information; numbering is consistent with full-length pri-mir-16-1 (Fig. 1A). The imino resonances labeled α, ζ, and η are located in the non-native Gα:C-C:Gη clamp and 5′-UUCGζ-3′ tetraloop capping pri-mir-16ΔΔ and pri-mir-16Δloop, respectively, and connected using dashed drop-lines. B, pri-mir-16Δss. C, pri-mir-16Δloop. D, pri-mir-16-1 RNA.

To complement the pri-mir-16 constructs, we produced three recombinant DGCR8 variants to be tested in our binding studies, DGCR8Δ275, DGCR8PC, and DGCR8core (Fig. 1B). DGCR8Δ275 lacks the first 275 amino acids but retains WW and heme-binding domains, two dsRBDs and the Drosha interaction/trimerization domain and is competent for both dimerization and pri-miRNA processing (13, 14, 48). DGCR8PC includes residues 484–750 and represents the processing-competent (PC) core (48). DGCR8core (residues 493–706) lacks the Drosha interaction domain but retains the tandem dsRBDs and is therefore unable to participate in pri-miRNA processing but is RNA binding-competent (14, 49).

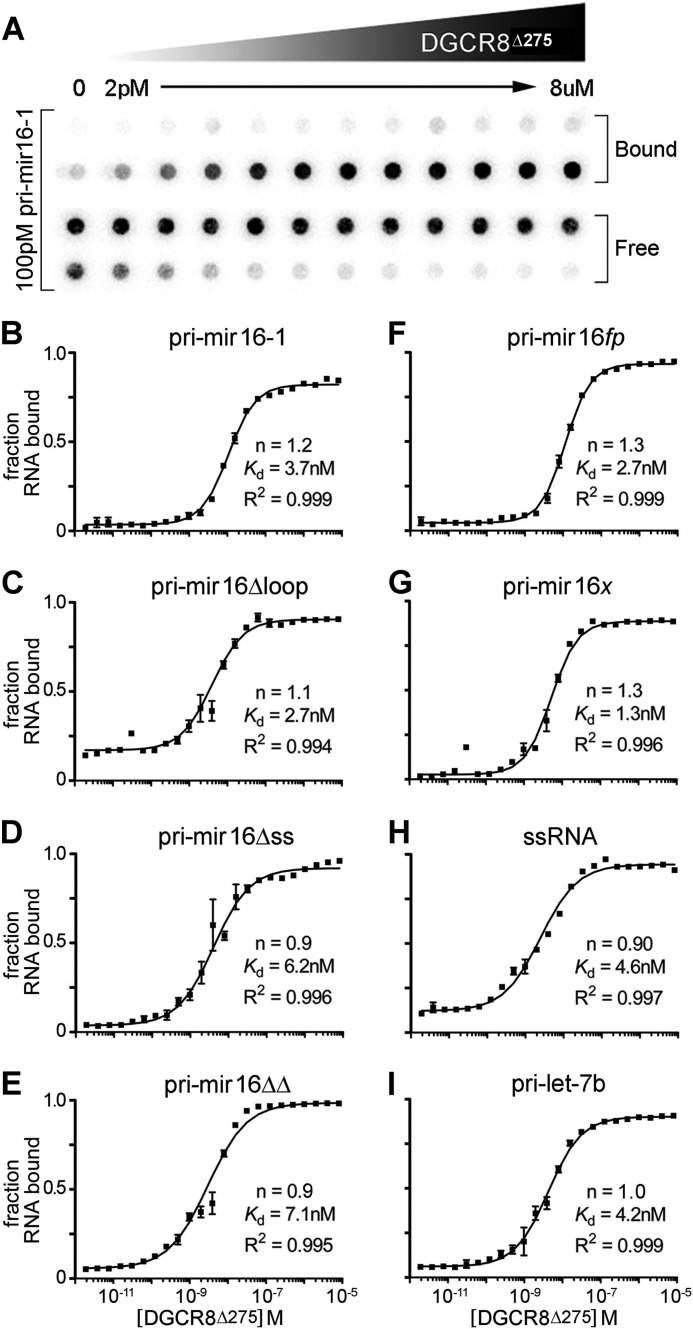

DGCR8Δ275/pri-miRNA interactions were monitored by filter binding assays. As shown in Fig. 3B, DGCR8Δ275 bound pri-mir-16-1 with low nanomolar affinity (3.7 ± 0.9 nm), in qualitative agreement with previously published filter binding experiments (14). Surprisingly, DGCR8Δ275 bound pri-mir-16Δloop, Δss, and ΔΔ constructs with similar affinities (Fig. 3, C–E, summarized in Table 1) and Hill coefficients, suggesting that neither the ss-flanking regions nor the terminal loop are determinants for specific recognition by DGCR8.

FIGURE 3.

Filter binding measurement of DGCR8 binding affinity. A, representative raw data from dot-blot double filter binding experiments. Protein concentration increases from 2 pm to 8 μm spanning two bracketed rows. B–I, quantified results of recombinant DGCR8Δ275/RNA binding, represented as the fraction of bound RNA. All experiments were performed with 100 pm 32P-5′-end-labeled RNA. The axes of all graphs are identical, and the values are shown along the left and bottom of the figure. All curves have been calculated from at least four independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Summary of filter binding experiments

Calculations were based on at least four independent experiments, and curves were fit using a nonlinear least sum of squares analysis with variable slope (see Equation 1 and see under “Experimental Procedures”).

| 16-1 | 16Δloop | 16Δss | 16ΔΔ | 16fp | 16x | ssRNA | let-7b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGCR8 | Kd = | 3.7 ± 0.9 nm | 2.7 ± 0.8 nm | 6.2 ± 2.3 nm | 7.1 ± 1.9 nm | 2.7 ± 0.7 nm | 1.3 ± 0.6 nm | 4.6 ± 1.0 nm | 4.2 ± 1.1 nm |

| (Δ275) | n = | 1.2 ± .05 | 1.1 ± .09 | 0.9 ±.07 | 0.9 ± .05 | 1.3 ± .01 | 1.3 ± .09 | 0.9 ± .05 | 1.0 ± .06 |

| R2 = | 0.999 | 0.994 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.999 | |

| DGCR8 | Kd = | 73 ± 15 nm | 87 ± 19 nm | 77 ± 23 nm | 74 ± 23 nm | 115 ± 23 nm | |||

| (core) | n = | 1.5 ± .12 | 1.7 ± .15 | 1.5 ± .16 | 1.6 ± .18 | 1.1 ± .08 | |||

| R2 = | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

To test whether pri-mir-16 mutants contain enough ssRNA in internal loops or bulges to attract DGCR8, we have modified the pri-mir-16ΔΔ construct to produce a fully paired hairpin (pri-mir-16fp) by altering unpaired and bulged nucleotides to effectively eliminate ssRNA and maximize duplex stability (Fig. 1A). DGCR8Δ275 was still able to bind pri-mir-16fp with affinity and cooperativity equivalent to that of pri-mir-16-1, Δloop, Δss, and ΔΔ (Fig. 3F). To rule out the possibility that DGCR8Δ275 recognition of pri-mir-16-1 is driven by a sequence determinant common to all of our RNA substrates, we tested pri-mir-16x (Fig. 1A), a Quikfold (50)-predicted 82-nt hairpin co-transcribed with mir-16-1 and mir-15a on the DLEU2 lincRNA (long intergenic noncoding RNA) (51, 52). Located 397 nt upstream of mir-16-1, pri-mir-16x is overlooked by the Microprocessor. As shown in Fig. 3G, filter binding analysis revealed that DGCR8Δ275 binds pri-mir-16x with no discernable loss of affinity or cooperativity relative to the other RNAs tested. To test whether the lack of significant variation in our results could be explained by DGCR8Δ275 recognition of predominantly dsRNA elements, we produced an 87-nt ssRNA principally composed of nine tandem CCCCUAAA repeats (Fig. 1A). NMR analysis of exchangeable imino protons confirmed that no stable secondary structure was formed in this transcript (data not shown). Finally, we also generated a pri-let-7b transcript to serve as a second bona fide pri-miRNA substrate. Again, DGCR8Δ275 bound both constructs with Kd and Hill values consistent with other RNA substrates (Fig. 3, H and I).

Similarly, binding affinities and cooperativity measurements remained consistent when we analyzed DGCR8core and a subset of the pri-miRNA variants, even though the affinities were reduced ∼10-fold for DGCR8core, compared with DGCR8Δ275 (Table 1). Collectively, our filter binding experiments demonstrate that DGCR8 recognizes the tested RNA variants with high affinity and Hill coefficients ranging from 0.9 to 1.8. None of the DGCR8 constructs tested in filter binding demonstrated a pronounced tendency to bind cooperatively beyond a dimer model.

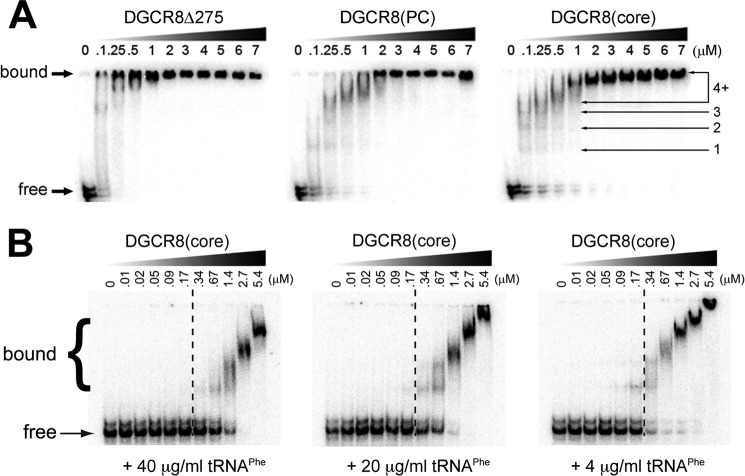

To directly detect oligomeric DGCR8-RNA complex formation, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with DGCR8Δ275, DGCR8PC, or DGCR8core and the pri-mir-16 transcript. As seen in Fig. 4A, progressively more truncated variants of DGCR8 all populate similar heterogeneous complexes with pri-mir-16-1. Additionally, DGCR8/pri-miRNA interactions reveal a “smearing” effect rather then discrete band formation, which could indicate that DGCR8 binds pri-miRNA transiently and with variable stoichiometry, sampling different regions of the substrate until excess protein effectively saturates all potential binding sites on the RNA at any given time. EMSA titrations of DGCR8core into radiolabeled pri-mir-16-1 in the presence of varying amounts of nonspecific competitor yeast tRNAPhe revealed that increasing amounts of tRNA increase the apparent Kd values for the DGCR8core/pri-mir-16-1 complex (Fig. 4B). Thus, on the basis of our EMSA results, DGCR8's mode of binding resembles other dsRBDs (such as protein kinase R (PKR) (53)) that interact with RNA through transient and/or noncooperative interactions featuring multiple, potentially overlapping RNA-binding sites with comparable affinities. Taken together, our binding data imply that DGCR8 alone is not able to distinguish miRNA-containing hairpins from other RNA species but rather retains high, indiscriminate affinity for RNA within its dsRBDs.

FIGURE 4.

EMSA visualization of DGCR8-pri-mir-16-1 complex stoichiometries and apparent affinities. A, representative gel shifts of pri-mir-16-1 with DGCR8 variants exhibit similar formation of higher order complexes. B, EMSA titration of DGCR8core into pri-mir-16-1 RNA, with the bands corresponding to free pri-mir-16-1, multimeric DGCR8core·pri-mir-16-1 complexes, and DGCR8core concentration through the titration denoted. EMSA reaction buffers contained 40, 20, and 4 μg ml−1 of nonspecific competitor yeast tRNAPhe (Sigma), respectively.

DGCR8/pri-miRNA Binding Monitored by NMR

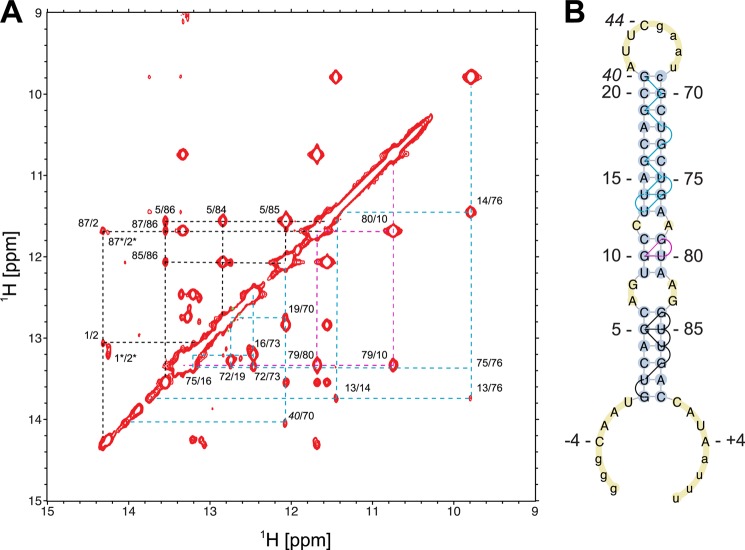

In the interest of reducing overall molecular weight for NMR studies, we used a 65-nt version of pri-mir-16-1 (pri-mir-16lower, Fig. 1A) that is correctly processed in vitro (data not shown) (17). Using NMR spectroscopy, we have determined that the secondary structure of pri-mir-16lower includes 5′- and 3′-ssRNA overhangs, a 21-nt stem featuring tandem G-A mismatches and a C-A mismatch, and a stable 8-nt loop (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

NMR imino assignments and secondary structure determination of pri-mir-16lower. A, sequential imino-imino proton NOE assignment paths are shown by different colors for A-form helical stems I (black), II (magenta), and III (cyan). The spectrum is labeled with assignment information. B, NMR-based secondary structure of the lower stem of pri-mir-16lower. The secondary structure representation was generated using PseudoViewer (74); pri-mir-16lower numbering is consistent with full-length pri-mir-16-1 (Fig. 1).

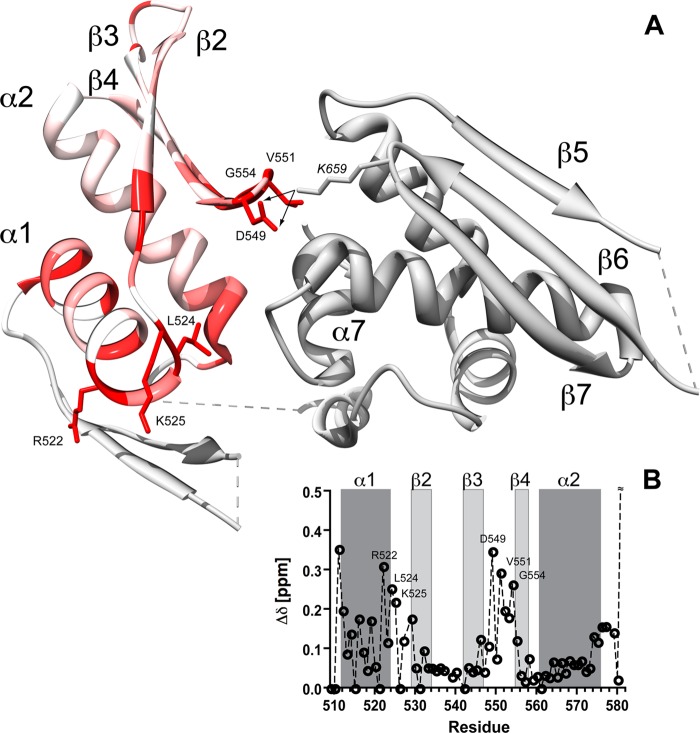

Our recent NMR analysis confirmed that our purified DGCR8core contains all of the secondary structure features of the reported crystal structure (Fig. 7A) (27, 49). Furthermore, we observed pronounced chemical shift differences between the backbone amide 1H,15N-correlations of an isolated RBD1 domain and those of the RBD1-RBD2-containing DGCR8core construct (Fig. 6). This demonstrates that the two tandem RBD domains interact with each other in solution confirming earlier reports based on the crystal structure (49) and MD simulations (54).

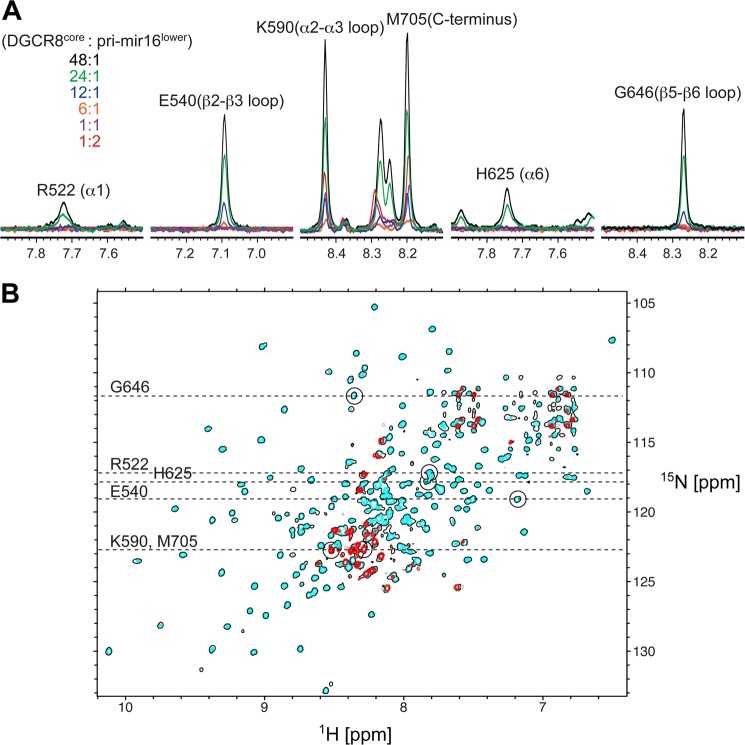

FIGURE 7.

DGCR8core·pri-mir-16lower complex formation monitored by NMR. A, traces taken through the TROSY cross-peaks of Arg-522 (located in α1), Glu-540 (β2-β3 loop), Lys-590 (α2-α3 interdomain loop)/Met-705 (C terminus), His-625 (α6), and Gly-646 (β5-β6 loop) during the titration at various 2H,15N-DGCR8core:pri-mir-16lower stoichiometric ratios ranging from 48:1 (black) to 1:2 (red). B, 800 MHz 1H,15N TROSY spectra of 2H,15N-DGCR8core recorded at 25 °C in the absence of pri-mir-16lower (cyan contours) and at protein:RNA stoichiometric ratios of 48:1 (single black contour) and 1:2 (red contours). Dashed-horizontal lines indicate traces shown in A with cross-peak positions circled and assignments given.

FIGURE 6.

Chemical shift perturbation analysis of DGCR8RBD1 and DGCR8core constructs. A, color-coded representation of combined backbone amide 1HN and 15N chemical shift differences of DGCR8RBD1 (residues 509–582) and DGCR8core (residues 493–706). Backbone ribbon color of the DGCR8 crystal structure (PDB code 2YT4) varies between white (Δδ = 0 ppm) and red (Δδ ≥0.2 ppm). Residues Val-581 and Lys-582 (Δδ ≥ 0.6 ppm) at the very C-terminal end of the RBD1 construct have been omitted for clarity. Side chains of residues with Δδ ≥0.2 ppm are shown. The location of a putative salt bridge involving Asp-549 and Lys-659 (italic) inferred from the distances observed in the x-ray structure is indicated using arrows. B, backbone amide 1HN and 15N chemical shift differences of DGCR8RBD1 (residues 509–582) in comparison with DGCR8core (residues 493–706) as a function of residue number. Secondary structure elements are numbered and highlighted using gray boxes.

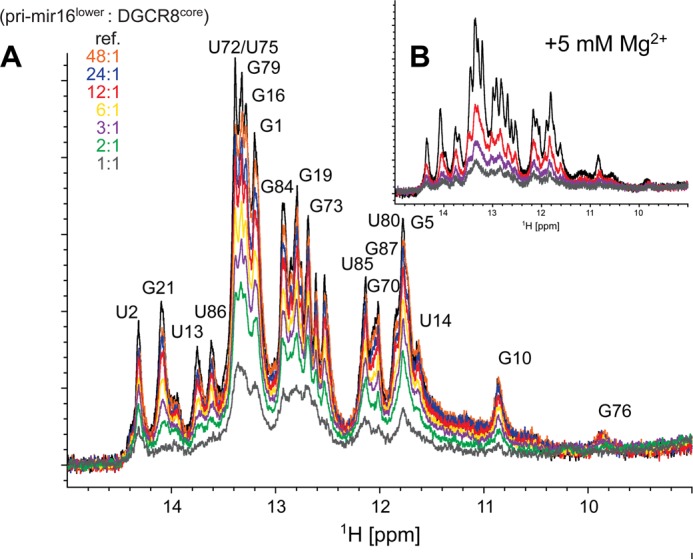

To characterize the interactions between DGCR8 and pri-miRNA at single residue resolution, an NMR titration study was performed in which 1H,15N-TROSY spectra of 2H,15N-labeled DGCR8core were monitored upon addition of increasing amounts of RNA. pri-mir-16lower was titrated into 250 μm 2H,15N-DGCR8core to produce protein/RNA solutions ranging from 48:1 to 1:2 molar ratios. We observed differential broadening of backbone amide 1H,15N correlations evident even at low concentrations of pri-mir-16lower (Fig. 7). Because binding and dissociation between DGCR8core and pri-mir-16lower occurred on the intermediate time scale, 1H,15N correlation experiments do not reveal discrete resonances for RNA-bound and free states commonly observed for systems in fast or slow exchange. Thus, our protein-RNA interface analysis focused on differential broadening at a molar ratio where most protein resonances were still observed (24:1 ratio of DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower).

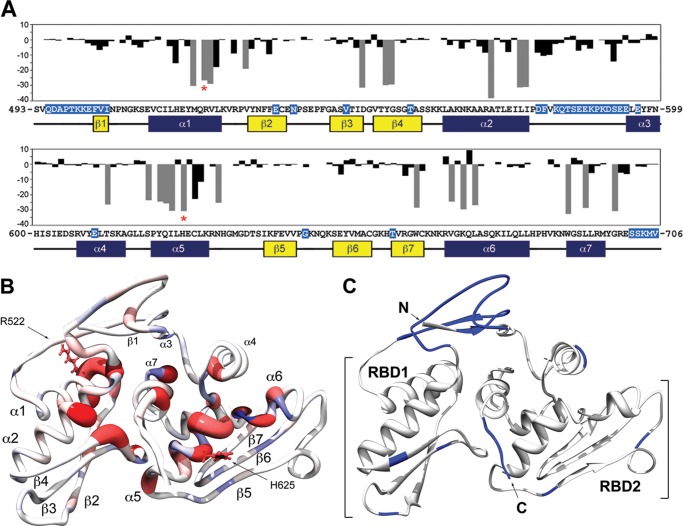

Differences in amide proton LW (ΔLW) upon RNA binding were calculated by subtracting the LWbound of a given residue in the presence of sub-stoichiometric RNA from the LWfree observed in the absence of RNA (Fig. 8A). A value of zero indicates no change in LW. The ΔLW values for infinitely broadened resonances (Fig. 8A, gray bars) were calculated assuming a conservative LWbound of 50 Hz, which corresponds to the largest 1H-TROSY LWbound observable at 800 MHz. The residues with the largest change in line width (most negative ΔLW) values map to the first and second helices of the each dsRBD motif (RBD1:α1 and α2, RBD2:α5 and α6) (Figs. 7 and 8B). This pattern of RNA-dependent line broadening correlates with previously characterized canonical RBD interactions in which approximately one helical turn of a successive minor and major groove dsRNA is occupied by the α-helical regions of the α-β-β-β-α dsRNA-binding domain (20, 55). However, no significant broadening is detected for either the β2-β3 loop located in RBD1 or the β5-β6 loop in RBD2, which one would predict to contact an adjacent minor groove in a canonical dsRBD-dsRNA interaction (Figs. 7 and 8B). Instead, noticeable broadening occurs within the β4, β7, and α7 regions. For its part, α7 has been shown to stabilize the DGCR8core through extensive intramolecular contacts with both dsRBDs (49, 54). Therefore, line broadening in this region is not likely attributed to direct association with pri-mir-16lower but is probably reporting on conformational exchange on an intermediate time scale between bound and free DGCR8core forms. Ultimately, line broadening analysis of our DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower titration suggests some variation in archetypal dsRNA binding for both RBD subunits of the DGCR8core where three structural elements of each dsRBD, the N-terminal α-helix, the loop between β1 and β2, and the C-terminal second helix, engage adjacent minor grooves and the intervening groove of dsRNA (56).

FIGURE 8.

1H,15N-TROSY resonance broadening map for binding of DGCR8core to pri-mir-16lower. A, changes in 1H LW (ΔLW) of 250 μm 2H,15N-labeled DGCR8core in the presence of 10.4 μm pri-mir-16lower versus the amino acid sequence of DGCR8core. ΔLW values were calculated by subtracting the LWbound of a given residue from the LWfree. ΔLW for infinitely broadened resonances (gray bars) were calculated assuming a conservative LWbound of 50 Hz corresponding to the largest 1H-TROSY LWbound observable at 800 MHz. Secondary structure elements (α1–7 and β1–7) as determined by chemical shift index using TALOS+ (75) are identified below the residue number. B, color-coded worm representation of DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower titration at a 24:1 protein/RNA ratio. Secondary structure elements are numbered and indicated. Worm thickness of the DGCR8core crystal structure (PDB code 2YT4) varies between 2.00 (ΔLW = −38.3 Hz, red) and 0.25 (ΔLW = 9.2 Hz, blue). Missing crystal residues were modeled and energy-minimized in Chimera (76). C, DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower titration at a 1:2 protein/RNA ratio. Individual RBDs are numbered; N and C termini are shown and indicated. The 39 visible TROSY peaks remaining in the presence of excess RNA predominantly map to the N and C termini, and flexible linker regions of the DGCR8core crystal structure (PDB code 2YT4) and are mapped and highlighted in blue on the protein sequence (A).

Finally, we tested whether protein resonances, which are broadened beyond detection at substoichiometric RNA ratios, would sharpen as a result of changes in exchange regime brought about by the formation of specific, stable interactions in the presence of excess pri-mirR16lower. Over the course of the titration and at the end point ratio 1:2 DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower, the vast majority of assigned backbone amide resonances was broadened beyond detection. The remaining 30 residues experienced negligible chemical shift perturbations and map primarily to the flexible linker between RBD1 and RBD2 (residues Asp-579 to Glu-594), the N terminus, including strand β1 (residues Gln-495 to Ile-505), and the C terminus of the protein (residues Ser-702 to Val-706) (Figs. 7 and 8C). Overall, our findings indicate that DGCR8core exchanges between and among pri-mir-16lower-binding sites on the intermediate chemical shift time scale leading to differential line broadening.

Such a model was further corroborated by a titration revealing global imino proton line broadening of pri-mir-16lower in the presence of increasing amounts of DGCR8core (Fig. 9A). Divalent cations often stabilize important RNA tertiary structures. Therefore, titrations were repeated in the presence of 5 mm MgCl2. Imino proton chemical shift changes observed for pri-mir-16lower and larger RNA variants (Fig. 1A) in the presence of Mg2+-cations were invariably small and did not exceed 0.04 ppm (data not shown). Moreover, intermediate exchange kinetics prevailed in the presence of Mg2+ cations (Fig. 9B). The NMR titration data also suggest that the structure of DGCR8core may not be significantly perturbed by the pri-mir-16lower interaction because chemical shifts of resonances observable during the titration are mostly unchanged.

FIGURE 9.

pri-mir-16lower·DGCR8core complex formation monitored by NMR. A, 850 MHz imino one-dimensional jump-return echo experiment of pri-mir-16lower collected at 298 K (black) labeled with assignment information; numbering is consistent with full-length pri-mir-16-1 (Fig. 1). RNA/protein molar ratios ranging from 48:1 (orange) to 1:1 (gray) were achieved by adding dilute aliquots of DGCR8core to a 250 μm pri-mirlower sample in NMR buffer. B, same as above with 5 mm MgCl2 added to the NMR buffer.

DGCR8/pri-miRNA Binding Monitored by PFG-NMR

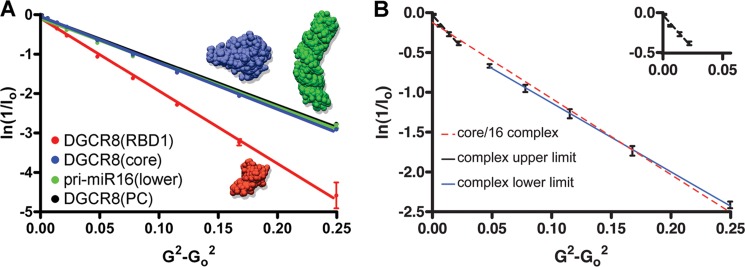

A distinct advantage of PFG-NMR methods is that translational self-diffusion coefficients can be determined under experimental conditions (protein and RNA concentration, temperature, and viscosity) identical to those used for collecting the NMR titration data described above. Because diffusion measurements are sensitive to changes in molecular size and shape, these experiments provide a supplementary characterization of DGCR8/pri-mir-16-1 association to complement our line broadening analysis. The results of PFG-NMR experiments are reported in Table 2. A single (average) diffusion coefficient was observed in all experimental measurements of free DGCR8 protein variants or pri-mir-16lower, as evident from linear correlations with R values ≥0.996 (Fig. 10A).

TABLE 2.

Summary of least squares regressions and experimental and theoretical translational self-diffusion constants and hydrodynamic radii

| DGCR8RBD1 | DGCR8core | DGCR8PC | pri-mir-16lower | DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower complex | Complex lower limit | Complex upper limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | −18.34 | −11.768 | −11.21 | −11.24 | −9.541 | −13.78 | −8.641 |

| ln(I/I0) versus (g2-g02)a | R ≤ 0.997 | R ≤0.998 | R ≤ 0.997 | R ≤0.996 | R ≤ 0.990 | R ≤ 0.999 | R ≤ 0.999 |

| D | 13.561 | 8.657 | 8.246 | 8.267 | 7.017 | 10.132 | 6.356 |

| 10−11 m2 s−b | ± 0.044 | ± 0.100 | ± 0.040 | ± 0.121 | ± 0.223 | ± 1.024 | ± 0.153 |

| D calc | 13.83 | 9.815 | 8.716 | ||||

| 10−11 m2 s−1c | ± 0.098 | ||||||

| RHexp | 17.9 | 28.0 | 29.4 | 34.5 | 24.1 | 38.1 | |

| Åd | ± 1.0 | ± 0.3 | ± 0.1 | ± 1.1 | ± 2.6 | ± 0.9 | |

| RHcalc | 17.5 | 24.7 | |||||

| Åe |

a Slopes were derived from linear least squares fits using three replicate measurements (30 data points total for the 1st 5 columns; 15 data points were used to determine upper and lower boundaries, 6th and 7th columns). Data analysis was performed using Prism 4.0 software.

b Translational diffusion constants derived from Equation 2 at 298 K in aqueous (90:10% H2O/D2O) buffer solutions containing 135 mm KCl. Three replicate experiments were performed, and the resulting average values for D with corresponding standard deviations are reported.

c Theoretical translational diffusion constants were calculated from atomic level structures available for DGCR8RBD1 and DGCR8core using HYDROPRO (PDB accession codes 1X47 and 2YT4, respectively) (71, 72). All-atom models for the 65 nucleotide pri-mir-16lower were generated using MC-Sym from sequence and NMR-based secondary structure (37). 132 structures were clustered using MC-Sym, and five representative structures displaying various bend angles were analyzed using HYDROPRO. The resulting average value for D with corresponding standard deviation is reported.

d Experimental hydrodynamic radii assuming spherical shapes derived from Equation 3. Three replicate experiments were performed, and the resulting average values for RH with corresponding standard deviations are reported.

e Theoretical hydrodynamic radii calculated from atomic level structures available for DGCR8RBD1 and DGCR8core using HYDROPRO (PDB accession codes 1X47 and 2YT4, respectively).

FIGURE 10.

Pulsed field gradient NMR and DGCR8-pri-mir-16-1 complex models. A, natural log scale of signal integrals of BPPLED-PFG 1H NMR experiments as a function of gradient amplitude squared and linear data fits. Diffusion of individual protein and RNA components is as follows: DGCR8RBD1 (red), DGCR8core (blue), pri-mir-16lower (green), and DGCR8PC (black). B, diffusion of 1:2 molar ratio DGCR8core·pri-mir-16lower complexes as follows: average (dashed red line), lower limit (solid blue line), and upper limit (dashed black line). The inset (G2-G02 = 0.00 to 0.05, ln(1/I0) = 0.0 to −0.5) in the upper right corner shows the best fit for the upper complex limit (dashed black line).

Possible explanations for a slower diffusion rate (8.7 ± 0.01 × 10−11m2·s−1) of the 214-residue DGCR8core (larger apparent RH) in comparison with calculated values (9.8 × 10−11m2·s−1) include differences between the solution structure and the crystal structure used for the prediction, intermolecular oligomerization, and/or the presence of unfolded protein regions. In the case of intermolecular oligomerization, one would expect the slower diffusion to be caused by partial dimerization. Assuming exchange averaging between a monomer and a dimer on the diffusion time scale, we calculated a 47% dimer population of the DGCR8core. In good agreement with results previously published (49), our SEC analysis confirmed an estimated molecular mass of 31 kDa for the DGCR8core, significantly larger than the theoretical molecular mass of 24.2 kDa (data not shown). The overall agreement of experimental and calculated translational diffusion coefficients and hydrodynamic radii for the DGCR8 variants and pri-mir-16lower in isolation confirms that physically meaningful data could be obtained for macromolecular DGCR8·pri-mir-16 complexes.

For the DGCR8core·pri-mir-16lower complex, diffusion rates of the protein in the presence of excess RNA (1:2 molar ratio) revealed a deviation from linearity (R = 0.990) (Fig. 10B), suggesting a polydisperse system described by Equation 2. Linear correlations obtained after subtracting the contributions from the slowly diffusing complex (i.e. elimination of last five points) or the faster diffusing component (i.e. elimination of first five points) yielded upper and lower boundaries of D = 10.1 ± 1.02 × 10−11 m2·s−1 with (R = 0.999) and D = 6.4 ± 0.15 × 10−11m2·s−1 (R = 0.999). Extrapolated to infinite dilution, Stokes radii of RH = 24.1 ± 2.6 Å and 38.1 ± 0.9 Å can thus be estimated for the smallest and largest diffusing spherical particles for the DGCR8core·pri-mir-16lower complex exchanging on the diffusion time scale. The smallest diffusing molecule is likely unbound DGCR8core given the close agreement with the predicted RHcalc value of 24.7 Å.

Recombinant DGCR8Δ275 Is an Active Microprocessor Component

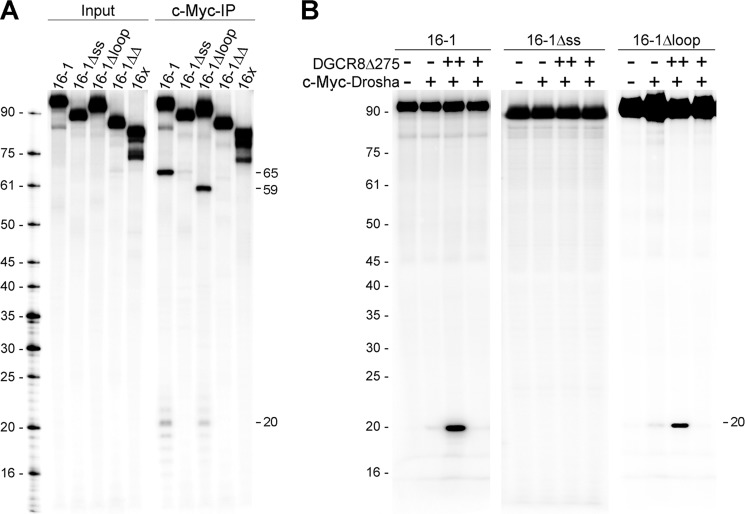

We performed in vitro Microprocessor assays that mimic the first step in miRNA biogenesis to examine the relationship between observed DGCR8/pri-miRNA binding patterns and processing. When incubated with immunoprecipitated Microprocessor, the pri-mir-16-1 and 16Δloops were efficiently processed to release respective 65- and 59-nt pre-miRNAs as well as the 20-nt 5′ and 3′ reaction by-products (Fig. 11A). However, pri-mir-16 variants lacking ss-flanking RNA (16Δss and 16ΔΔ) were not cleaved by the Microprocessor, in agreement with previously published work (14, 17, 18). In addition, no cleavage products were observed when pri-mir-16x was used in the processing assay. These data demonstrate that only a distinct subgroup, including pri-mir-16-1 and 16Δloop, is able to productively engage the Microprocessor, even though all RNA constructs display similar binding by DGCR8.

FIGURE 11.

In vitro pri-miRNA processing assays. A, processing of uniformly labeled pri-miRNAs in the absence (Input) or in the presence (c-myc-IP) of immunoprecipitated Microprocessor. Assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Sizes of oligonucleotide DNA markers are shown on the left. 5′, 3′, and pre-miRNA processing products are indicated on the right. B, DGCR8Δ275-dependent pri-miRNA processing. Recombinant DGCR8Δ275 was incubated with stringently washed IP-Drosha. 32P-5′-End-labeled pri-mir-16-1 variants were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of Microprocessor components. Images in A and B are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To address whether DGCR8's RNA specificity determinant could reside in the truncated portion of the DGCR8Δ275 constructs, we have performed in vitro processing with a DGCR8Δ275-reconstituted Microprocessor. c-Myc-Drosha alone did not efficiently process pri-mir-16-1, 16Δss, or 16Δloop (Fig. 11B). However, when incubated with purified recombinant DGCR8Δ275, 5′ cleavage products were observed for pri-mir-16-1 and 16Δloop but not 16Δss, confirming that recombinant DGCR8Δ275 is a properly folded, active component of a highly specific in vitro pri-miRNA processing complex.

Taken together, our binding and processing data strongly suggest that DGCR8 alone is not the specificity determinant for recognition of bona fide miRNA-containing hairpins. Instead, DGCR8 works in concert with Drosha to promote specific recognition and processing of pri-miRNA transcripts.

DGCR8-Drosha Co-immunoprecipitation

In the assumption that the DGCR8-Drosha complex provides the specificity for pri-miRNA recognition, it is necessary that DGCR8 and Drosha can form heterodimers prior to pri-miRNA binding. To probe for the prerequisite heterodimer, a co-immunoprecipitation assay was performed in the absence or presence of RNases. Western blot analysis of Drosha-immunoprecipitated complexes revealed the presence of DGCR8 in extracts treated with either RNase inhibitor or RNase A/T1 mix (data not shown). This observation confirms earlier reports by Han et al. (10) and suggests that association of Drosha and DGCR8 does not depend on the availability of RNA substrate molecules.

DISCUSSION

Accessory dsRNA-binding proteins involved in small RNA pathways have been shown to be required for efficient and accurate modulation of specific RNA species, when part of multiprotein complexes (10, 57, 58). Despite the importance and characterized functions of endonuclease-associated dsRBD-containing proteins in miRNA biogenesis, few reports have described the detailed mechanistic and structural nature of their interactions with RNase IIIs or specific RNA substrates (59).

Previous results from filter binding experiments form the basis for a recognition model in which highly cooperative binding by DGCR8 is the distinguishing characteristic of specific pri-miRNA recognition (14). Although our Kd values are in agreement with those previously reported for filter binding (13, 49), we have been unable to demonstrate conclusive deviations in binding cooperativity among various RNA substrates. Our direct, EMSA-based observation of higher order complex formation involving DGCR8core, which lacks a previously identified trimerization domain, also questions a generalized model of pri-miRNA recognition involving stepwise, cooperative binding mediated by the DGCR8 trimerization domain (14).

We employed concentrations of 100 pm of end-labeled RNA and a low salt buffer (50 mm NaCl) in filter binding assays and observed tighter affinity and lower Hill coefficients for the heme-bound DGCR8Δ275/pri-mir-16-1 interaction when compared with previously published studies by Faller et al. (13, 14) using unspecified concentrations of body-labeled pri-mir21 and pri-mir30a in complex with DGCR8Δ275 in a reaction buffer containing 85 mm NaCl. We observed reduced affinity for the DGCR8core/pri-mir-16-1 interaction using EMSA in a high salt buffer (150 mm KCl, data not shown). Thus, the apparent Kd values for DGCR8 binding to pri-mir-16-1 generally decrease with increasing salt concentration.

Hill coefficients often do not provide accurate estimates of the number of binding sites (60), particularly when multisite complex formations are involved. In general, nitrocellulose filter binding describes only macroscopic association parameters that are composite averages of individual binding sites and cooperativity constants. Here, one must assume a relationship between the number of ligands bound and complex retention by the nitrocellulose membrane to accurately describe the interaction. Senear et al. (61) have concluded that it is impossible to correctly resolve microscopic binding and cooperativity constants of a multisite complex by filter binding. The apparent steepness of dose-response curves and the corresponding Hill coefficients (n) depend on invariant 32P-labeled RNA concentration below the Kd. When RNA concentrations approach the Kd value, the resulting best fits to the Hill equation no longer provide accurate information on either Kd or n (60, 62). Dimerization at higher DGCR8 concentration can potentially alter binding characteristics that would further complicate reliable curve fitting. Using SEC and NMR diffusion measurements, we and others (49) have detected a dimerization tendency for DGCR8 variants. Finally, because we investigated DGCR8-pri-mir-16-1 and pri-let-7b complex formation, we cannot rule out the possibility that the highly cooperative association previously observed could be a specific feature of DGCR8 binding to pri-mir30a and pri-mir21 studied by Faller et al. (13, 14). Although processed by the Microprocessor, alternative biogenesis pathways for pri-mir21 independent of DGCR8 have been suggested (63).

UV cross-linking experiments in the presence of varying amounts of competitors have previously been employed to establish relative affinities of DGCR8 to pri-miRNA (17). Although DGCR8 could be cross-linked with decreasing efficiency to diverse targets such as pri-mir-16-1, a small interfering (si)RNA duplex and ssRNA, the ability to compete for DGCR8 binding revealed some advantage for ss-dsRNA junctions. Furthermore, a length dependence where shorter RNA constructs competed gradually less efficiently with the longer pri-miRNA was observed. Our DGCR8core/pri-mir-16-1 EMSA and increasing apparent Kd values in the presence of varying amounts of nonspecific competitor yeast tRNAPhe suggest that DGCR8core/RNA interactions are nonspecific. Consistent with a nonspecific binding mode, the results obtained from competition experiments may have uncovered a correlation between efficient competition and the number of nonspecific binding sites provided by the various competitors.

To overcome the binding assay limitations described above and to obtain independent information about the DGCR8core·pri-mir-16 complex equilibrium in solution, we conducted NMR titration and diffusion measurements. Results from NMR titrations strongly suggest that the DGCR8core·pri-mir-16lower complex represents a nonspecific interaction. The observed line broadening in the absence of chemical shift perturbations indicates the formation of transient, nonspecific complexes (64). Results obtained from diffusion measurements further corroborated nonspecific DGCR8core/pri-mir-16lower binding models as we observed interconverting free DGCR8core and complexes with hydrodynamic radii of ∼38.1 Å.

These findings are consistent with reports of other dsRBD-containing proteins involved in small RNA pathways. For example, dsRBDs of both HYL1 (HYPONASTIC LEAVES 1) and PKR that exhibit noncanonical binding and extensive line broadening have been shown to bind RNA without apparent specificity (55, 65, 66). Similarly, we have been unable to detect by NMR nucleotide-specific changes to RNA targets complexed with DGCR8core. Analogous to the protein spectra, pri-mir-16 imino-proton peaks were broadened globally and severely. This result suggests that DGCR8 dsRBDs simultaneously bind overlapping interfaces of the RNA in a manner resembling nonspecific PKR·dsRNA complex formation (66). Finally, the Dicer accessory dsRBD-containing protein-transactivating response RNA-binding protein and two homologs, including PKR, were most recently shown to diffuse along dsRNA substrates, which is clearly an activity conceivably adopted by DGCR8 to anchor Drosha-DGCR8 heterodimers (67).

Although our nonspecific DGCR8/pri-miRNA interaction model differs from the proposed cooperative recognition model (14), several common observations have been described. Two studies have identified that helix 2 in each α-β-β-β-α dsRNA-binding domain of DGCR8 is important for pri-miRNA recognition (15, 49). In good agreement, our NMR titration analysis recognizes the first and second helices of each dsRBD motif (RBD1:α1 and α2, RBD2:α5 and α6) as primary pri-mir-16-1 interaction interfaces. The binding affinity of DGCR8 for the 160-nt P4–P6 domain of the Tetrahymena ribozyme is similar to the ones observed for bona fide pri-miRNA substrates (14). Likewise, we cannot distinguish ssRNA, fully paired (pri-mir-16fp) or random hairpin (pri-mir-16x) interactions involving DGCR8 from pri-miRNA-derived substrates based on Kd values. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of oligomeric (DGCR8)n·pri-miRNA complexes using filter binding assays, SEC, and low resolution electron tomography (14). Our NMR titration and diffusion analysis directly probe solution equilibria and offer further support for oligomeric, albeit nonspecific, binding of DGCR8 to RNA substrates. Furthermore, we were able to visualize DGCR8·pri-miRNA complexes with variable stoichiometry using EMSA.

DGCR8 alone shows no preference for a particular RNA substrate, yet we and others have demonstrated through in vitro processing assays that the Microprocessor is highly selective when cleaving its RNA targets (17, 18). Thus, we conclude that DGCR8-RNA substrate binding is not the specificity determinant of pri- to pre-miRNA processing, and a model of stepwise pri-miRNA recognition and Drosha recruitment by DGCR8 seems unlikely. Because known requirements common to all Microprocessor substrates remain broad and include 70-nt hairpins with unpaired flanking regions (19), the functional implication of our finding is that the concerted action of a DGCR8·Drosha complex is required for effective recognition of miRNA-containing transcripts. Consistently, recent studies revealed that association with the HIV-1 LTR requires the presence of both Microprocessor components, Drosha and DGCR8 (68). An alternative scenario, where Drosha can distinguish its target among nonspecific DGCR8·pri-miRNA complexes cannot be strictly ruled out based on our results.

Importantly, stable association of DGCR8 and Drosha occurs independently of RNA (10). Presumably, this protein/protein interaction leads to enhanced RNA binding specificity by way of conformational modulation of DGCR8's dsRBDs, by steric limitation of binding opportunities to constrained regions of the RNA hairpin, or a combination of both scenarios. The DGCR8/RNA interaction and other examples (55, 67, 69, 70) suggest that dsRBDs associated with miRNA biogenesis are generally nonspecific binders. Although this form of association might seem less than satisfying, nonspecific and/or loose binding can be an important characteristic for an accessory protein. Thus, the biological implication is that nonspecific associations can greatly enhance the RNA binding flexibility of a protein complex, which is in good agreement with reports demonstrating DGCR8's involvement in controlling the fate of diverse classes of RNA such as mRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, long noncoding RNAs, and pri-miRNAs (24). For the Microprocessor in particular, the ability to bind a broad range of loosely related hairpin structures could be critical to carry out its universal function.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Hennig laboratory for stimulating discussions and comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge the support of the Hollings Marine Laboratory NMR Facility for this work.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants MCB 0845512 and DBI 1126230 (to M. H.).

- miRNA

- microRNA

- pre-miRNA

- precursor miRNA

- pri-miRNA

- primary miRNA

- PFG

- pulsed field gradient

- dsRBD

- double-stranded RNA-binding domain

- ssRNA

- single-stranded RNA

- nt

- nucleotide

- BPPLED

- bipolar pulse pair longitudinal eddy current delay

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel D. P. (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Voinnet O. (2009) Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell 136, 669–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dreyer J. L. (2010) New insights into the roles of microRNAs in drug addiction and neuroplasticity. Genome Med. 2, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Farazi T. A., Spitzer J. I., Morozov P., Tuschl T. (2011) miRNAs in human cancer. J. Pathol. 223, 102–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferland-McCollough D., Ozanne S. E., Siddle K., Willis A. E., Bushell M. (2010) The involvement of microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1565–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wittmann J., Jack H. M. (2011) microRNAs in rheumatoid arthritis: midget RNAs with a giant impact. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, Suppl. 1, 92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee S. J., Jiko C., Yamashita E., Tsukihara T. (2011) Selective nuclear export mechanism of small RNAs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yi R., Qin Y., Macara I. G., Cullen B. R. (2003) Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 17, 3011–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee Y., Ahn C., Han J., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J., Lee J., Provost P., Rådmark O., Kim S., Kim V. N. (2003) The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 425, 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K. H., Kim Y. K., Jin H., Kim V. N. (2004) The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 18, 3016–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barr I., Smith A. T., Chen Y., Senturia R., Burstyn J. N., Guo F. (2012) Ferric, not ferrous, heme activates RNA-binding protein DGCR8 for primary microRNA processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1919–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barr I., Smith A. T., Senturia R., Chen Y., Scheidemantle B. D., Burstyn J. N., Guo F. (2011) DiGeorge critical region 8 (DGCR8) is a double-cysteine-ligated heme protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16716–16725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Faller M., Matsunaga M., Yin S., Loo J. A., Guo F. (2007) Heme is involved in microRNA processing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Faller M., Toso D., Matsunaga M., Atanasov I., Senturia R., Chen Y., Zhou Z. H., Guo F. (2010) DGCR8 recognizes primary transcripts of microRNAs through highly cooperative binding and formation of higher-order structures. RNA 16, 1570–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wada T., Kikuchi J., Furukawa Y. (2012) Histone deacetylase 1 enhances microRNA processing via deacetylation of DGCR8. EMBO Rep. 13, 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeng Y., Yi R., Cullen B. R. (2005) Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha. EMBO J. 24, 138–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K. H., Nam J. W., Heo I., Rhee J. K., Sohn S. Y., Cho Y., Zhang B. T., Kim V. N. (2006) Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell 125, 887–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeng Y., Cullen B. R. (2005) Efficient processing of primary microRNA hairpins by Drosha requires flanking nonstructured RNA sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27595–27603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Auyeung V. C., Ulitsky I., McGeary S. E., Bartel D. P. (2013) Beyond secondary structure: primary-sequence determinants license pri-miRNA hairpins for processing. Cell 152, 844–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramos A., Grünert S., Adams J., Micklem D. R., Proctor M. R., Freund S., Bycroft M., St Johnston D., Varani G. (2000) RNA recognition by a Staufen double-stranded RNA-binding domain. EMBO J. 19, 997–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stefl R., Xu M., Skrisovska L., Emeson R. B., Allain F. H. (2006) Structure and specific RNA binding of ADAR2 double-stranded RNA binding motifs. Structure 14, 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu H., Henras A., Chanfreau G., Feigon J. (2004) Structural basis for recognition of the AGNN tetraloop RNA fold by the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of Rnt1p RNase III. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8307–8312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stefl R., Oberstrass F. C., Hood J. L., Jourdan M., Zimmermann M., Skrisovska L., Maris C., Peng L., Hofr C., Emeson R. B., Allain F. H. (2010) The solution structure of the ADAR2 dsRBM-RNA complex reveals a sequence-specific readout of the minor groove. Cell 143, 225–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Macias S., Plass M., Stajuda A., Michlewski G., Eyras E., Cáceres J. F. (2012) DGCR8 HITS-CLIP reveals novel functions for the Microprocessor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 760–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roth B. M., Hennig M. (2011) in RNA Structure Determination by NMR: Combining Labeling and Pulse Techniques (Dingley A. J., Pascal S. M., eds) pp. 205–228, IOS Press, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (eds) (1989) Molecular Cloning, Vol. 3, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roth B. M., Hennig M. (2012) Backbone 1H(N), 13C, and 15N resonance assignments of the tandem RNA-binding domains of human DGCR8. Biomol. NMR Assign, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arraiano C. M., Barbas A., Amblar M. (2008) Characterizing ribonucleases in vitro examples of synergies between biochemical and structural analysis. Methods Enzymol. 447, 131–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee Y., Kim V. N. (2007) In vitro and in vivo assays for the activity of Drosha complex. Methods Enzymol. 427, 89–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goddard T. D., Kneller D. G. (2004) SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sklenar V., Bax A. (1987) Spin-echo water suppression for the generation of pure-phase two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 74, 469–479 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lippens G., Dhalluin C., Wieruszeski J. M. (1995) Use of a water flip-back pulse in the homonuclear NOESY experiment. J. Biomol. NMR 5, 327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bax A., Griffey R. H., Hawkins B. L. (1983) Correlation of proton and nitrogen-15 chemical shifts by multiple quantum NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 55, 301–315 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dingley A. J., Grzesiek S. (1998) Direct observation of hydrogen bonds in nucleic acid base pairs by internucleotide (2)J(NN) couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 8293–8297 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pervushin K., Ono A., Fernández C., Szyperski T., Kainosho M., Wüthrich K. (1998) NMR scaler couplings across Watson-Crick base pair hydrogen bonds in DNA observed by transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 14147–14151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parisien M., Major F. (2008) The MC-Fold and MC-Sym pipeline infers RNA structure from sequence data. Nature 452, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sattler M., Schleucher J., Griesinger C. (1999) Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 34, 93–158 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wostenberg C., Quarles K. A., Showalter S. A. (2010) Dynamic origins of differential RNA binding function in two dsRBDs from the miRNA “Microprocessor” complex. Biochemistry 49, 10728–10736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chou J. J., Baber J. L., Bax A. (2004) Characterization of phospholipid mixed micelles by translational diffusion. J. Biomol. NMR 29, 299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu D. H., Chen A. D., Johnson C. S. (1995) An improved diffusion-ordered spectroscopy experiment incorporating bipolar-gradient pulses. J. Magn. Reson. A 115, 260–264 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stejskal E. O., Tanner J. E. (1965) Spin diffusion measurements: Spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. J. Chem. Phys. 42, 288–292 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harris K. R., Woolf L. A. (2004) Temperature and volume dependence of the viscosity of water and heavy water at low temperatures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 49, 1064–1069 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kestin J., Imaishi N., Nott S. H., Nieuwoudt J. C., Sengers J. V. (1985) Viscosity of light and heavy water and their mixtures. Phys A: Stat. Theo. Phys. 134, 38–58 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jones G., Dole M. (1929) The viscosity of aqueous solutions of strong electrolytes with special reference to barium chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 51, 2950–2964 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dordick R., Korson L., Drost-Hansen W. (1979) High-precision viscosity measurements: I. Aqueous solutions of alkali chlorides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 72, 206–214 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Landthaler M., Yalcin A., Tuschl T. (2004) The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr. Biol. 14, 2162–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeom K. H., Lee Y., Han J., Suh M. R., Kim V. N. (2006) Characterization of DGCR8/Pasha, the essential cofactor for Drosha in primary miRNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 4622–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sohn S. Y., Bae W. J., Kim J. J., Yeom K. H., Kim V. N., Cho Y. (2007) Crystal structure of human DGCR8 core. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 847–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Markham N. R., Zuker M. (2005) DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W577–W581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Corcoran D. L., Pandit K. V., Gordon B., Bhattacharjee A., Kaminski N., Benos P. V. (2009) Features of mammalian microRNA promoters emerge from polymerase II chromatin immunoprecipitation data. PLoS One 4, e5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Corcoran M. M., Hammarsund M., Zhu C., Lerner M., Kapanadze B., Wilson B., Larsson C., Forsberg L., Ibbotson R. E., Einhorn S., Oscier D. G., Grandér D., Sangfelt O. (2004) DLEU2 encodes an antisense RNA for the putative bicistronic RFP2/LEU5 gene in humans and mouse. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 40, 285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams B. R. (1999) PKR: a sentinel kinase for cellular stress. Oncogene 18, 6112–6120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wostenberg C., Noid W. G., Showalter S. A. (2010) MD simulations of the dsRBP DGCR8 reveal correlated motions that may aid pri-miRNA binding. Biophys. J. 99, 248–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang S. W., Chen H. Y., Yang J., Machida S., Chua N. H., Yuan Y. A. (2010) Structure of Arabidopsis HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 and its molecular implications for miRNA processing. Structure 18, 594–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tian B., Bevilacqua P. C., Diegelman-Parente A., Mathews M. B. (2004) The double-stranded-RNA-binding motif: interference and much more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 1013–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gregory R. I., Yan K. P., Amuthan G., Chendrimada T., Doratotaj B., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. (2004) The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432, 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haase A. D., Jaskiewicz L., Zhang H., Lainé S., Sack R., Gatignol A., Filipowicz W. (2005) TRBP, a regulator of cellular PKR and HIV-1 virus expression, interacts with Dicer and functions in RNA silencing. EMBO Rep. 6, 961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nowotny M., Yang W. (2009) Structural and functional modules in RNA interference. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 286–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weiss J. N. (1997) The Hill equation revisited: uses and misuses. FASEB J. 11, 835–841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Senear D. F., Brenowitz M., Shea M. A., Ackers G. K. (1986) Energetics of cooperative protein-DNA interactions: comparison between quantitative deoxyribonuclease footprint titration and filter binding. Biochemistry 25, 7344–7354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hall K. B., Kranz J. K. (1999) Nitrocellulose filter binding for determination of dissociation constants. Methods Mol. Biol. 118, 105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yi R., Pasolli H. A., Landthaler M., Hafner M., Ojo T., Sheridan R., Sander C., O'Carroll D., Stoffel M., Tuschl T., Fuchs E. (2009) DGCR8-dependent microRNA biogenesis is essential for skin development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 498–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Marintchev A., Frueh D., Wagner G. (2007) NMR methods for studying protein-protein interactions involved in translation initiation. Methods Enzymol. 430, 283–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rasia R. M., Mateos J., Bologna N. G., Burdisso P., Imbert L., Palatnik J. F., Boisbouvier J. (2010) Structure and RNA interactions of the plant microRNA processing-associated protein HYL1. Biochemistry 49, 8237–8239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ucci J. W., Kobayashi Y., Choi G., Alexandrescu A. T., Cole J. L. (2007) Mechanism of interaction of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding domain of protein kinase R with short dsRNA sequences. Biochemistry 46, 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Koh H. R., Kidwell M. A., Ragunathan K., Doudna J. A., Myong S. (2013) ATP-independent diffusion of double-stranded RNA-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 151–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wagschal A., Rousset E., Basavarajaiah P., Contreras X., Harwig A., Laurent-Chabalier S., Nakamura M., Chen X., Zhang K., Meziane O., Boyer F., Parrinello H., Berkhout B., Terzian C., Benkirane M., Kiernan R. (2012) Microprocessor, Setx, Xrn2, and Rrp6 co-operate to induce premature termination of transcription by RNAPII. Cell 150, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Parker G. S., Eckert D. M., Bass B. L. (2006) RDE-4 preferentially binds long dsRNA and its dimerization is necessary for cleavage of dsRNA to siRNA. RNA 12, 807–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Parker G. S., Maity T. S., Bass B. L. (2008) dsRNA binding properties of RDE-4 and TRBP reflect their distinct roles in RNAi. J. Mol. Biol. 384, 967–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fernandes M. X., Bernadó P., Pons M., García de la Torre J. (2001) An analytical solution to the problem of the orientation of rigid particles by planar obstacles. Application to membrane systems and to the calculation of dipolar couplings in protein NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 12037–12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. García De La Torre J., Huertas M. L., Carrasco B. (2000) Calculation of hydrodynamic properties of globular proteins from their atomic-level structure. Biophys. J. 78, 719–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zuker M. (2003) Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Han K., Lee Y., Kim W. (2002) PseudoViewer: automatic visualization of RNA pseudoknots. Bioinformatics 18, S321–S328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009) TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 44, 213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]