Abstract

We report observations of stratospheric CO2 that reveal surprisingly large anomalous enrichments in 17O that vary systematically with latitude, altitude, and season. The triple isotope slopes reached 1.95 ± 0.05(1σ) in the middle stratosphere and 2.22 ± 0.07 in the Arctic vortex versus 1.71 ± 0.03 from previous observations and a remarkable factor of 4 larger than the mass-dependent value of 0.52. Kinetics modeling of laboratory measurements of photochemical ozone–CO2 isotope exchange demonstrates that non–mass-dependent isotope effects in ozone formation alone quantitatively account for the 17O anomaly in CO2 in the laboratory, resolving long-standing discrepancies between models and laboratory measurements. Model sensitivities to hypothetical mass-dependent isotope effects in reactions involving O3, O(1D), or CO2 and to an empirically derived temperature dependence of the anomalous kinetic isotope effects in ozone formation then provide a conceptual framework for understanding the differences in the isotopic composition and the triple isotope slopes between the laboratory and the stratosphere and between different regions of the stratosphere. This understanding in turn provides a firmer foundation for the diverse biogeochemical and paleoclimate applications of 17O anomalies in tropospheric CO2, O2, mineral sulfates, and fossil bones and teeth, which all derive from stratospheric CO2.

For most materials containing oxygen, the relative abundances of its three stable isotopes (16O, 17O, and 18O) fall on a “mass-dependent” fractionation line (1) with a ln17O-ln18O three-isotope slope† near 0.5, which is well-predicted by statistical thermodynamics (3) and chemical reaction rate theories (4). In other words, 17O is usually one-half as depleted or enriched as 18O when measured relative to 16O and relative to those same ratios in an international standard. Discoveries of large deviations from a mass-dependent slope of 0.5 in meteorites (5) and ozone (6, 7), resulting in nonzero 17O anomalies (i.e., Δ17O = ln17O − 0.52 ln18O ≠ 0), have led to many applications tracing the histories and inventories of materials throughout the solar system (1), despite continuing debate about their chemical or physical origins (e.g., refs. 1, 8).

For ozone, the non–mass-dependent enrichments in 17O and 18O have a three-isotope slope of 0.65–1.0 (e.g., ref. 9) and have been traced to anomalous kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) in O3 formation:

where M is any collision partner (10–12). Although much progress has been made in understanding ozone’s non–mass-dependent isotopic composition (12–14), the theoretical basis in chemical physics is still unresolved (15–17). In addition, whether 17O anomalies in other species––such as CO2, N2O, sulfates, and nitrates (e.g., ref. 18)––result solely from transfer from O3 or from additional anomalous KIEs remains unclear. Stratospheric CO2, for example, attains at least part of its observed non–mass-dependent isotopic composition (19–24) via reactions 2–3b (25–28):

The observed three-isotope slope for stratospheric CO2 ranges from ∼1.2 to 1.7, much larger than for O3. To explain the difference, non–mass-dependent isotope effects beyond O3 formation have been postulated (19, 29), including a coincidental near-resonance for 17O12C16O2* or a nuclear spin/spin-orbit coupling effect in [3a]. In addition, three-isotope slopes for CO2 measured in laboratory mixtures of UV-irradiated O2 or O3 and CO2 (29–32), slopes calculated from photochemical models of laboratory experiments (30) and the stratosphere (27, 28), and slopes from observations show remarkable disagreements. For example, three-isotope slopes for CO2 in laboratory experiments typically vary from about 0.8 to 1.0 (29, 30, 32) not the value of 1.7 that has come to be expected for the stratosphere (22, 33). Although one laboratory study has yielded a slope up to 1.8 (31), the experiment was performed at unrealistically high O3/CO2 ratios and shows unusual behavior relative to all other published experiments. Experiments under nearly identical conditions but longer irradiation times (32) yielded a slope near 1, suggesting that the higher slope in the high O3/short irradiation time experiments likely results from non–mass-dependent isotope effects in O3 photodissociation due to O3 self-shielding, which is not relevant for atmospheric conditions; thus, the apparent agreement with previous stratospheric observations is arguably fortuitous, as discussed further below. In addition, ln17O was measured directly in only one previous laboratory study (32), whereas it was inferred from mass balance in all others, which adds additional uncertainty (e.g., if unknown 13C isotope effects might affect the results due to the isobaric interference between 13C16O16O and 12C17O16O in mass spectrometry measurements). Finally, Liang et al. (27, 28) calculate a three-isotope slope of 1.5 for CO2 in their model at latitudes >25°N that shows little temporal or spatial variation in the lower and middle stratosphere. The current level of disagreement between experiments, atmospheric observations, and atmospheric modeling shows that isotope exchange between O3 and CO2 is still not well understood.

Here, we report measurements of ln17O and ln18O of stratospheric CO2 that reveal much larger three-isotope slopes than expected and their systematic variation with latitude, altitude, and season. We also report time-dependent laboratory and modeling results that demonstrate that anomalous KIEs in O3 formation alone quantitatively account for the triple isotope composition of CO2 in the laboratory. Combining laboratory and stratospheric results, we show that differences in temperature, relative rates of mass-dependent reactions, and vertical versus quasihorizontal transport rates can plausibly explain differences in the ln17O-ln18O relationships between the laboratory and stratosphere and within the stratosphere. The results thus provide a deeper understanding of contemporary stratospheric CO2 isotope variations, the underlying isotope chemistry, and a sounder foundation for the biogeochemical, paleoclimate, and paleoatmospheric applications of 17O anomalies in materials that derive their signals from stratospheric CO2 (34–40).

Stratospheric CO2 was separated cryogenically from whole air samples collected by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) ER-2 aircraft (41) in winter 1999–2000 during the SAGE III Ozone Loss and Validation Experiment (SOLVE) (42) and a September 2004 balloon flight (43) at 34°N. The isotopic composition was measured on a Finnigan MAT 252 isotope ratio mass spectrometer using the CeO2 equilibration technique (44). Additional sampling and measurement details are provided in Materials and Methods and SI Appendix. Results are shown in Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Tables S1–S4. Samples of high-latitude air (>55°N) determined to be in the polar vortex from nitrous oxide (N2O) and potential temperature (θ) measurements (45) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) exhibit a three-isotope slope from a bivariate linear least-squares regression of 2.22 ± 0.07(1σ). Samples collected at midlatitudes (25–55°N) and in “midlatitude-like” (i.e., nonvortex) air at high latitudes (based on N2O and θ) yield a three-isotope slope of 1.95 ± 0.05. These slopes are significantly larger (Table 1) than the expected value of 1.71 ± 0.03 from Lämmerzahl et al. (22), with homogeneity of regression tests demonstrating that these differences with respect to the Lämmerzahl data are both significant at the 99% confidence interval (SI Appendix, Table S5). If only the new lower stratospheric (<21 km) samples are included in our midlatitude regression, the slope is 1.7 ± 0.2, closer to expectations but more variable. We believe this increased variability in the lower stratosphere is real (see below), although additional uncertainty from a smaller regression range may also contribute.

Fig. 1.

Stratospheric CO2 observations. Three isotope plot for the balloon (34°N) and “SOLVE” aircraft (24–83°N) samples, with previous observations: Thiemens (19) and Zipf and Erdman (20) are rocket samples from ∼34°N. Lämmerzahl (22) are balloon samples from 44° and 68°N. Alexander (21) are balloon samples from 68°N. Kawagucci (24) are balloon samples from 39° and 68°N. Data from Boering et al. (23) are not shown because of an earlier analytical mass-dependent artifact that affected ln17O and ln18O but not Δ17O. The mass-dependent fractionation line with slope 0.528 (red) and a hypothetical end member mixing line (black) with slope 1.7 (SI Appendix, Table S6) are also shown. The overall 1σ uncertainties for the SOLVE and Balloon 2004 data including both external precision and accuracy are ±0.1% for ln18O and ±0.5% for ln17O.

Table 1.

Summary of three isotope slopes for stratospheric CO2

| Source | Dates | Region | Altitude, km | N | Slope, ±1σ |

| SOLVE | 12/99–3/00 | High latitude/vortex | 11–20 | 24 | 2.22 ± 0.07 |

| SOLVE | 12/99–3/00 | High latitude/nonvortex and midlatitude | 11–20 | 11 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| SOLVE + balloon | 12/99–3/00, 9/04 | High latitude/nonvortex and midlatitude | 11–33 | 20 | 1.95 ± 0.05 |

Additional insight into the regional differences in slope is gained by examining Δln17O/Δln18O (i.e., the slope of a line defined by two points: the ln17O and ln18O isotopic composition of a sample and the isotopic composition of tropospheric CO2 with ln17O = 21.1% and ln18O = 40.2%) for individual datapoints from the rocket (19) and 2004 balloon datasets. Vertical profiles of CH4, N2O, and θ suggest the influence of air transported from more equatorial regions (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S3). The Δln17O/Δln18O values for these tropically influenced samples are typically larger than for samples with more midlatitude-like character based on CH4, N2O, and θ. These differences suggest that even larger slopes may be observable in the deep tropics and that transport and mixing of tropical air to 34°N contributes to the Δln17O/Δln18O variability in these profiles.

These systematic variations in Δln17O/Δln18O and three-isotope slopes with latitude, altitude, and season are not inconsistent with the previous observations of Lämmerzahl et al. (22) at 44°N and 68°N. The narrow range in slope of 1.71 ± 0.03 they measured has been considered the “standard” against which other measurements and model predictions should match (22, 33). However, the Lämmerzahl flights, based on their timing, would have likely always intercepted nonvortex extratropical air, yielding a relatively homogeneous three-isotope slope not necessarily representative of other regions, similar to how the long-lived tracers CH4 and N2O exhibit homogeneous nonvortex extratropical slopes distinct from tropical and vortex slopes. Satellite measurements of CH4 and N2O show CH4:N2O relationships that are compact (i.e., homogeneous) and distinct between three regions: the tropics, the extratropics, and the polar vortices after significant descent has occurred (46). In contrast, the region at 25 ± 10°N exhibits CH4:N2O correlations that are much less compact, consisting of inhomogeneous mixtures of tropical and midlatitude air (46). The CO2 isotopic composition is also a long-lived tracer (23, 27, 28) because the lifetime for isotope exchange with O3 is always at least an order of magnitude longer than stratospheric transport timescales, even at 45 km where O(1D) peaks (27, 28); thus, transport and mixing affect the CO2 isotopic composition similarly to CH4 and N2O. By analogy, homogeneous three-isotope slopes for CO2 can be observed poleward of 35°N except in Arctic vortex air in January–March (42); the tropical and late vortex three-isotope slopes can be distinct from the nonvortex/extratropical relationships; and the 25 ± 10°N “mixed region” would be an inhomogeneous mixture, as observed. These variations in three-isotope slopes thus appear to be explicable and robust across high-precision CO2 datasets.

These systematic variations with latitude and season we observe may also account for at least some of the variability in what have been considered to be the noisier datasets shown in Fig. 1 (20, 21, 24). For example, the dataset of Alexander et al. (21) consists of six samples that were collected in or near the polar vortex and which indeed show a higher three-isotope slope of 2.1 ± 0.6(1σ, n = 6), although the variability is high and the uncertainty in slope means it is not statistically different from the previous, lower slope datasets. It is not clear whether the variability is due to the small number of samples and real atmospheric variability (such as moving in and out of vortex air) or to possible measurement artifacts. Our vortex data and interpretation presented here suggest that at least some of the variability may be real. Similarly, some of Kawagucci et al.’s datapoints (24) overlap with our larger slope datapoints, but they report themselves that a linear fit to their data yields a slope of 1.63 ± 0.05(1σ, n = 58) and that their slope and data in general are not statistically nor characteristically different from the Lämmerzahl et al. dataset. If additional unpublished trace gas data and geophysical parameters are available for their samples, it may be possible to investigate their outliers at larger or smaller Δln17O/Δln18O values. Otherwise, whether these outliers are explained by atmospheric variability or by a lower measurement precision for their online CuO equilibration isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) technique (as the much more scattered relationship between their Δ17O of CO2 and N2O mixing ratio measurements may suggest (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) is unclear. Homogeneity of regression tests demonstrate that the differences in slope between our “vortex” and the Kawagucci data and between our “midlatitude” and the Kawagucci data are statistically significant at the 99% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S5). Finally, the rocket dataset reported by Zipf and Erdman (20), which also lacks information on other long-lived tracer and potential temperature data, overlaps with our dataset, showing a curvilinear ln17O–ln18O relationship that links our lower and middle stratospheric data with the middle and upper stratospheric rocket data reported by Thiemens et al. (19); this dataset is thus also consistent with the idea that we put forth here that a linear ln17O–ln18O relationship of 1.7 with a small SD of <0.1 cannot represent the entire stratosphere, in contrast with the now widely held assumption that it does.

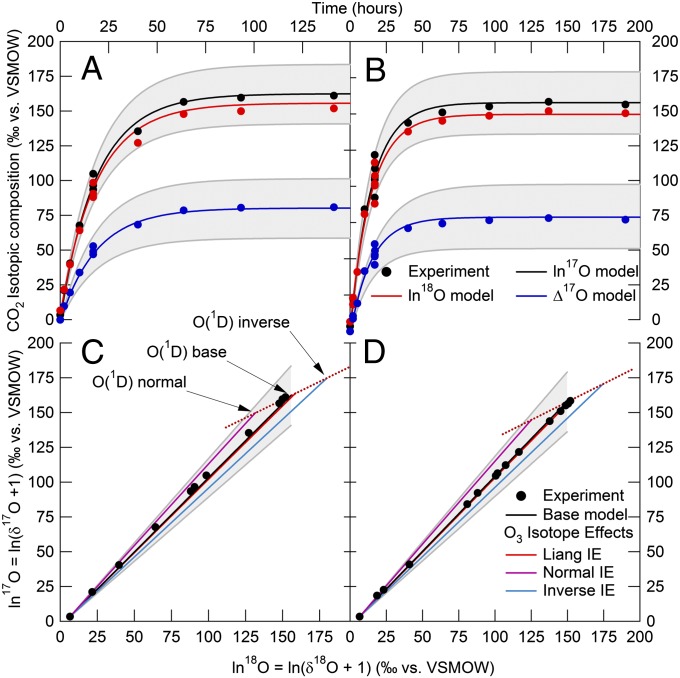

To investigate processes that could lead to the larger Δln17O/Δln18O values and three-isotope slopes we observe, O2 and CO2 mixtures near atmospheric mixing ratios were irradiated with UV light (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix). The CO2 isotopic composition was measured (SI Appendix, Table S7) and compared with results from a time-dependent photochemical kinetics model we developed using KINTECUS software (SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S10). The model accurately predicts both the time dependence and the steady-state values for ln17O, ln18O, and Δ17O of CO2 (Fig. 2 and Table 2). These results demonstrate that anomalous KIEs in O3 formation can quantitatively explain the triple isotope composition of CO2 in the laboratory at atmospherically relevant O2, O3, and CO2 mixing ratios without invoking additional anomalous KIEs or other unknown effects to account for the data. Importantly, the model uses molecular level rate coefficients without using empirical or phenomenological parameterizations of how the transfer of the anomaly from CO2 to O3 occurs at steady state used in previous work (28, 32). These results also demonstrate that slopes close to 1 are to be expected in most laboratory experiments using mercury lamps at atmospherically relevant O2/CO2 ratios and pressures below 150 torr. Indeed, even the very high O3/CO2 experiments of Shaheen et al. performed for long irradiation times (32) resulted in an experimental slope near 1, as did our photochemical model run under conditions similar to theirs, unlike the slope of 1.8 measured at very high O3/CO2 mixing ratios for short irradiation times (31). The short irradiation times combined with the narrow lines of a Hg lamp, large reactor volume, and very high amounts of O3 in the Chakraborty and Bhattacharya experiments (31) suggest that their 1.8 slope for CO2 results from non–mass-dependent isotopic self-shielding by O3 during O3 photodissociation and subsequent transfer to CO2 (32) rather than to processes simulating stratospheric isotope photochemistry in their experiment. In other words, isotopic self-shielding by O3 does not occur at the O3/CO2 levels in the atmosphere or in the near-atmospheric mixing ratio laboratory experiments, or even at the longer irradiation times in the high O3/CO2 experiments of Shaheen et al.; thus the apparent agreement between the three-isotope slope for CO2 of 1.8 with the previously expected value of 1.7 is likely fortuitous.

Fig. 2.

Experimental versus model results. Time evolution of the CO2 isotopic composition for the 50 torr (A) and 100 torr (B) UV irradiation experiments (symbols) and predictions from a photochemical kinetics model (lines). Shaded area shows uncertainty in the base model predictions, dominated by a conservative estimate of the uncertainty in kasymmetric for 17O16O16O formation. (C and D): Same as A and B in a three-isotope plot. Also included in different model scenarios (SI Appendix, Table S10) shown here are theoretical mass-dependent (“MD”) isotope effects in O3 photolysis at 254 nm (48); and large, hypothetical “normal” and “inverse” MD O3 photolysis isotope effects to illustrate how the three-isotope slope for CO2 is increased (normal) or decreased (inverse) along a mass-dependent line of slope 0.528 (red dotted line) as the MD isotope effects change the isotopic composition of O3 and O(1D), while leaving Δ17O (Table 2) essentially unchanged (to within small differences in the MD coefficients, λ, in Δ17O = ln17O−λln18O, which can range from 0.500 to 0.529; ref. 2). Under these laboratory conditions, there is only one O(1D) isotopic composition, so the CO2 isotopic composition evolves along a straight line connecting the O(1D) isotopic composition with that of the initial CO2.

Table 2.

Isotopic compositions from photochemistry experiments and kinetics modeling at 50 torr

| CO2* |

O3† |

|||||||

| Description | ln17O | ln18O | Slope | Δ17O‡ | ln17O | ln18O | Slope | Δ17O‡ |

| Experiment | 160 ± 1 | 151 ± 1 | 1.075 ± 0.004 | 80.7 ± 1.3 | 114 ± 7 | 138 ± 8 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 41 ± 6 |

| Model: base scenario | 163 | 156 | 1.067 | 80.3 | 113 | 139 | 0.81 | 39.2 |

| Liang photolysis IE§ | 164 | 159 | 1.056 | 80.2 | 110 | 134 | 0.82 | 39.3 |

| Normal photolysis IE | 150 | 132 | 1.172 | 80.4 | 119 | 151 | 0.79 | 39.2 |

| Inverse photolysis IE | 175 | 180 | 0.989 | 79.7 | 107 | 127 | 0.84 | 39.5 |

| Tropopause O2 and CO2 | 161 | 153 | 1.24 | 80.4 | 111 | 136 | 0.82 | 39.4 |

| Trop O2, CO2, 250 K | 140 | 124 | 1.41 | 74.5 | 96 | 117 | 0.83 | 34.8 |

| Trop O2, CO2, 220 K | 126 | 105 | 1.61 | 70.7 | 87 | 104 | 0.83 | 31.8 |

| Trop O2, CO2, 200 K | 117 | 92 | 1.84 | 68.0 | 80 | 95 | 0.84 | 29.7 |

Isotopic compositions are reported in ‰ on the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water scale. The modeled O(1D) isotopic composition is identical to that for CO2 because isotope effects in the O(1D) + CO2 isotope exchange reaction were not included in these model scenarios. Results for 100 torr are shown in SI Appendix, Table S11.

Experimental results for CO2 are an average (n = 2, ±1σ) of the measured values at isotopic steady state.

Experimental results for O3 are an average (n = 2, ±1σ combined error) of previous results at 50 torr (54, 57).

Δ17O = ln17O − 0.528 ln18O.

Theoretical mass-dependent O3 photolysis isotope effect at 254 nm (48).

The three-isotope slopes near 1.1 in experiments without isotopic self-shielding artifacts, however, are still much smaller than stratospheric observations. To investigate the possible origins of the laboratory–stratosphere differences in Δln17O/Δln18O values, we tested the sensitivity of the photochemical model to various inputs and processes (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Initializing the model with the tropospheric isotopic compositions of O2 and CO2 increases the slope from 1.067 to 1.24, a sensitivity previously noted (28, 31, 32). As the model temperature decreases to stratospheric values, the modeled slope increases further, to 1.84 at 200 K, based on several temperature-dependent O3 KIE measurements (47) and our estimates of others not yet measured (SI Appendix). The temperature decrease changes the predicted magnitudes of the O3 formation KIEs, which in turn alter the non–mass-dependent isotopic compositions of O3 and O(1D) and hence both the three-isotope slope and Δ17O of CO2. Introduction of mass-dependent isotope effects in any number of reactions can also change the three-isotope slope but leaves Δ17O effectively unchanged (Fig. 2 C and D and Table 2). For example, a mass-dependent O3 photolysis isotope effect at the experimental wavelength of 254 nm that isotopically depletes the remaining O3 (48, 49) will mass-dependently enrich O(1D) and CO2 and thus decrease the three-isotope slope. Similarly, but with opposite effect, a hypothetical mass-dependent isotope effect that isotopically enriches O3 will deplete O(1D) and CO2, thereby increasing the three-isotope slope. Broadband O3 photolysis in the stratosphere appears to mass-dependently enrich the remaining O3 (9), which would increase the slope for CO2. [Note that the existence of non–mass-dependent isotope effects in ozone photolysis has been proposed (50), but subsequent analysis (51) of those experimental results demonstrated that ozone formation was in fact responsible for the non–mass-dependent enrichments observed.] These experimental and modeling results support the hypothesis (18, 32) that temperature dependence of the O3 formation KIEs and mass-dependent O3 photolysis isotope effects likely cause the laboratory–stratosphere differences in the three-isotope slope for CO2, although differences in the importance of other mass-dependent isotope effects between the laboratory and stratosphere leading to isotopic depletions in O(1D) or CO2 cannot be ruled out.

Because the modeled ln17O–ln18O relationship for CO2 depends on temperature and O3 photolysis wavelengths and rates, which vary with altitude and latitude, these variables are the likely origin of the observed regional differences in stratospheric ln17O–ln18O relationships. Indeed, the O3 isotopic composition in the upper stratosphere shows regional differences attributed to UV photolysis (9), which was estimated to contribute 25–30% of the total enrichments in tropical O3 versus only 20–25% at midlatitudes. Our model sensitivities suggest that larger tropical O3 enrichments would increase the three-isotope slope of tropical CO2 relative to the extratropics, consistent with inferences from our mixed region observations.

With larger three-isotope slopes in upper tropical CO2, transport and mixing (which are much faster than CO2–O3 isotope exchange) then redistribute this tropical signal to other regions yet keep the slopes distinct, as for the CH4:N2O slopes. The larger tropical Δln17O/Δln18O values are transported into the mixed region at 25 ± 10°N at 25–40 km and will decrease as mixing into extratropical air proceeds (see below). Similarly, transport of this tropical upper stratospheric air by the residual circulation into the polar vortex generates the high Δln17O/Δln18O values there, similar to the winter buildup of O3 at high latitudes from the tropics (42). Because little photochemistry and vertical mixing occurs in the vortex, and a dynamic barrier at the vortex edge blocks most mixing with midlatitude air, the larger Δln17O/Δln18O tropical values are maintained in the vortex. When the vortex breaks up in spring, vortex and midlatitude air mix, decreasing the slope to the extratropical value. For example, apparent vortex remnants sampled in May 1998 at 22 km show a slope of 1.7 (22). Tracer measurements in similar vortex remnants in 1997 demonstrate that such remnants have mixed extensively with midlatitude air by May–June (42, 52). End member mixing of high-N2O and low-N2O air produces a mixing line of slope 1.7 (Fig. 1; SI Appendix, Table S6) using two samples with ranges of N2O concentrations similar to air that mixed during and after the 1997 vortex breakup (42, 52) and, more generally, similar to the mixing of low-N2O and high-N2O air that occurs on much larger spatial and temporal scales that are known to result in different CH4:N2O relationships in the tropics and extratropics (46).

Transport and mixing can also explain the larger scatter in slope in the lower stratosphere noted above. For example, Δln17O/Δln18O values for N2O < ∼220 parts per billion by volume (ppbv) are >1.7, but for N2O > ∼220 ppbv they vary between ∼0.5 and 1.7, are roughly inversely correlated with N2O, and increase with increasing Δ17O (Fig. 3). Moreover, the few outliers to the Δ17O and inverse N2O trends can be explained by (i) the degree of mixing of lower-N2O air from higher altitudes with higher-N2O air at lower altitudes, or (ii) the fact that the samples are from the lowermost stratosphere (θ< 380 K), which is a mixture of stratospheric air with air recently transported from the troposphere. These characteristics suggest that such lower stratospheric mixing creates real atmospheric variability in Δln17O/Δln18O values ranging between the entry (tropospheric) value of ∼0.5 to values ≥1.7 (also SI Appendix).

Fig. 3.

Variations in Δln17O/Δln18O of CO2. (A) Δln17O/Δln18O of CO2 versus N2O mixing ratio and (B) Δln17O/Δln18O of CO2 versus Δ17O of CO2; Δln17O/Δln18O = 1.7 is shown (dashed line) for reference. In general, the Δln17O/Δln18O values increase from a tropospheric, near–mass-dependent value to >1.6 as (A) N2O decreases and (B) Δ17O of CO2 increases, explaining at least part of the larger observed variability in Δln17O/Δln18O in the lower stratosphere where “younger,” high N2O air mixes with “older,” lower N2O air. Note that, for these samples, the trends in Δln17O/Δln18O are still apparent (even though the values change) even if we assume that the entry value for ln18O of CO2 entering the stratosphere from the troposphere can vary by ±0.5, either by applying the same offset for every point or by mimicking a seasonal variation within the dataset, and even though the overall 1σ uncertainty in the ln17O measurements including both accuracy and precision is ±0.5%.

In summary, we have shown that room temperature laboratory measurements of CO2–O3 isotope exchange near an atmospheric O2/CO2 mixing ratio can be quantitatively predicted with a first principles photochemical model and results in a linear ln17O–ln18O relationship for CO2 of 1.2 (starting with tropospheric O2 and CO2 isotopic compositions), whereas the ln17O–ln18O relationship for stratospheric CO2 can vary systematically with latitude, altitude, and time, ranging up to 2.2 in a sometimes curvilinear manner. Model sensitivities suggest that the laboratory–stratosphere and regional stratospheric differences originate from differences in mass-dependent isotope fractionation in O3 photolysis and in temperature due to the temperature dependence of the non–mass-dependent isotope effects in O3 formation. The latitude, altitude, and seasonal dependence of the observed three-isotope slopes suggests that stratospheric transport and mixing act to redistribute air with higher Δln17O/Δln18O values for CO2 from the tropical source region to the subtropics and into the polar vortex and then homogenize these higher values to the extratropical background of 1.7. Additional CO2 isotope measurements in the tropics could validate our hypothesis that the three-isotope slopes are greater there and provide additional constraints on photolysis isotope effects and the temperature dependence of the O3 formation KIEs, which also need further laboratory investigation. Also, 2D and 3D atmospheric models that include the latitude and altitude dependencies of the isotope chemistry inferred here and that can simulate realistic transport barriers are needed. For 17O anomalies in tropospheric CO2 (34), in O2 on short (35, 36) and glacial–interglacial (37, 38) timescales, in ancient mineral sulfates (39), and in fossilized bioapatite (40), we note the following: On one hand, productivity estimates for the current terrestrial and oceanic biospheres are on sounder footing because the isotope chemistry is no longer mysterious. Furthermore, these large three-isotope slopes do not affect previous estimates of the annual mean flux of Δ17O of CO2 to the troposphere because Δ17O is still similarly well-correlated with N2O in the lower stratosphere (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) (23). Importantly, the magnitude of Δ17O matters more than the magnitude of the three-isotope slopes, a point which is often overlooked. On the other hand, a sensitivity of Δ17O of CO2 to the temperature dependence of the anomalous O3 KIEs represents a possible caveat for longer timescale variations in Δ17O of O2, mineral sulfates, and bioapatite. Although Luz et al. (37) already elucidated the need to consider past changes in O3 and CO2 levels on Δ17O of O2, variations in stratospheric temperatures as climate changes may also affect Δ17O anomalies, especially if the temperature dependencies of the O3 KIEs are larger than estimated here.

Materials and Methods

Atmospheric Samples.

Air samples were collected between 24°N and 83°N and 11 and 20 km by the Whole Air Sampler instrument during the SOLVE mission (42) in January–March 2000 and at 34.5°N between 27 and 33 km by the Cryogenic Whole Air Sampler instrument aboard a high-altitude scientific balloon (43) launched from Fort Sumner, NM, in September 2004. Mixing ratios of trace gases in the samples were measured at the University of Miami or the National Center for Atmospheric Research, including N2O and CH4 using an HP5890 II+ series GC, before shipment to University of California Berkeley (UC Berkeley). At UC Berkeley, CO2 was separated from air and any residual water in a series of five liquid N2 and −75.5 °C ethanol–LN2 traps, respectively. The resulting aliquots of 30–60 μmol of CO2 were flame sealed into glass ampoules for subsequent IRMS analysis. Several samples exhibited water levels higher than stratospheric air [typically <10 parts per million by volume (ppmv)], indicating the sampler manifolds may have been temporarily contaminated with water. To eliminate potential artifacts from isotope exchange between CO2 and H2O either in the sample canisters or during the cryogenic separation that could increase Δln17O/Δln18O values, samples with residual water > 20 ppmv have been eliminated from analysis (SI Appendix).

Laboratory Experiments.

Mixtures of O2 (Scott Specialty Gases, 99.999%) and CO2 (Scott Specialty Gases, 99.998%) close to the atmospheric ratio (O2/CO2 ∼ 450) were introduced into a 2.2-L borosilicate glass bulb fitted with a fused quartz (Heraeus-Amersil, Inc.) “finger” extending into the interior of the bulb. A low-pressure Hg/Ar pen lamp (Oriel Instruments) with major emission lines at 184.9 and 253.7 nm was placed in the quartz finger to irradiate the bulb from the center. After irradiation for 0–190 h, the CO2 and resulting O3 were separated cryogenically from O2 using liquid nitrogen and were transferred to a sample tube containing nickel shavings. After heating at 60 °C for 15 min to decompose O3, the CO2 was separated cryogenically from the resulting O2 with liquid nitrogen and then measured by IRMS. In some experiments, the isotopic composition of O3 was determined by measuring the O2 from O3 decomposition at m/z values of 32, 33, and 34 by IRMS.

IRMS Measurements.

The triple oxygen isotope composition of CO2 was measured on a Finnigan MAT 252 IRMS at UC Berkeley using the CeO2 equilibration technique (44) on 12–18-μmol aliquots of the purified CO2 from the whole air samples or the purified CO2 from the laboratory experiments. Corrections to the IRMS signals for the presence of N2O in the stratospheric CO2 samples before CeO2 equilibration were made using measurements of the mixing ratio and isotopic composition of N2O made directly on the stratospheric whole air samples. External 1σ measurement precisions (n = 104 over 2 y) for ln18O, ln17O, and Δ17O of CO2 were ±0.05%, ±0.2%, and ±0.2%, respectively, where Δ17O = ln17O−0.528 ln18O. Including accuracy (SI Appendix) yields overall 1σ uncertainties of ±0.1%, ±0.5%, and ±0.5%, respectively.

Photochemical Kinetics Model.

The isotope-specific reaction kinetics occurring in the laboratory reaction bulb was predicted with KINTECUS software (53) using the Modified Bader–Deuflhard integrator to solve the system of stiff differential equations. The model is based on a previous model of O2–O3 isotope photochemistry (51) modified to include reactions relevant for CO2. In the “base model,” only KIEs in O3 formation and O + O2 isotope exchange were included, as measured or derived in earlier studies (10, 11). The pressure dependence of the O3 formation KIEs was derived from the O3 formation KIEs at low pressure and the pressure dependence of the O3 isotopic enrichments (54–56). In the model runs investigating sensitivity to temperature, the temperature dependence of the O3 formation KIEs was based on a combination of measurements of the temperature dependence of the KIEs for formation of the 18O-containing O3 isotopomers (47) and the temperature dependence of the 18O and 17O enrichments in O3 (9, 47) In model runs investigating sensitivity to possible isotope effects in O3 photolysis, a theoretical value at 254 nm from Liang et al. (48, 49) was used, as well as hypothetical limiting values for normal and inverse isotope effects. See SI Appendix for more details regarding the measurements and calculations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The stratospheric portion of this work was supported by NASA’s Upper Atmosphere Research Program (NNX09AJ95G to the University of California, Berkeley; and NNG05GN80G and NNX09AJ25G to the University of Miami) and the laboratory experiments and kinetics modeling by the National Science Foundation’s Experimental Physical Chemistry Program (CHE-0809973 to the University of California, Berkeley).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1213082110/-/DCSupplemental.

†Isotopic compositions are often reported as “δ”-values but a shorthand logarithmic notation is used here, as recommended by Luz and Barkan (2) both for convenience and to avoid unnecessary and uninteresting curvature that the use of δ-values can cause in three-isotope plots for the large laboratory enrichments measured. This logarithmic notation is defined as ln18O = ln[(18O/16O)sample/(18O/16O)standard] = ln[δ18O + 1], where (18O/16O)i is the ratio of the number of atoms of 18O to 16O in a sample or standard and δ18O = [{(18O/16O)sample/(18O/16O)standard}−1], and similarly for ln17O and δ17O.

References

- 1.Thiemens MH. History and applications of mass-independent isotope effects. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2006;34:217–262. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luz B, Barkan E. The isotopic ratios 17O/16O and 18O/16O in molecular oxygen and their significance in biogeochemistry. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2005;69(5):1099–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urey HC. The thermodynamic properties of isotopic substances. J Chem Soc. 1947 doi: 10.1039/jr9470000562. 10.1039/JR9470000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigeleisen J, Goeppert Mayer M. Calculation of equilibrium constants for isotopic exchange reactions. J Chem Phys. 1947;15(5):261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton RN, Grossman L, Mayeda TK. A component of primitive nuclear composition in carbonaceous meteorites. Science. 1973;182(4111):485–488. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4111.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiemens MH, Heidenreich JE., 3rd The mass-independent fractionation of oxygen: A novel isotope effect and its possible cosmochemical implications. Science. 1983;219(4588):1073–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.219.4588.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauersberger K. Ozone isotope measurements in the stratosphere. Geophys Res Lett. 1987;14(1):80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton RN. Solar System - Self-shielding in the solar nebula. Nature. 2002;415(6874):860–861. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krankowsky D, et al. Stratospheric ozone isotope fractionations derived from collected samples. J Geophys Res. 2007;112(D8):D08301. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauersberger K, Erbacher B, Krankowsky D, Nickel R, Nickel R, Guenther J. Ozone isotope enrichment: Isotopomer-specific rate coefficients. Science. 1999;283(5400):370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen C, Guenther J, Mauersberger K, Krankowsky D. Kinetic origin of the ozone isotope effect: A critical analysis of enrichments and rate coefficients. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2001;3(21):4718–4721. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauersberger K, Krankowsky D, Janssen C, Schinke R. Assessment of the ozone isotope effect. In: Bederson B, Walther H, editors. Advances in Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics. Vol 50. San Diego: Elsevier Academic; 2005. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao YQ, Marcus RA. Strange and unconventional isotope effects in ozone formation. Science. 2001;293(5528):259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schinke R, Grebenshchikov SY, Ivanov MV, Fleurat-Lessard P. Dynamical studies of the ozone isotope effect: A status report. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2006;57:625–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.57.032905.104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanov MV, Grebenshchikov SY, Schinke R. Quantum mechanical study of vibrational energy transfer in Ar-O3 collisions: Influence of symmetry. J Chem Phys. 2009;130(17):174311. doi: 10.1063/1.3126247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kryvohuz M, Marcus RA. Coriolis coupling as a source of non-RRKM effects in ozone molecule: Lifetime statistics of vibrationally excited ozone molecules. J Chem Phys. 2010;132(22):224305. doi: 10.1063/1.3430514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaderi N, Marcus RA. Bimolecular recombination reactions: Low pressure rates in terms of time-dependent survival probabilities, total J phase space sampling of trajectories, and comparison with RRKM theory. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115(18):5625–5633. doi: 10.1021/jp111833m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenninkmeijer CAM, et al. Isotope effects in the chemistry of atmospheric trace compounds. Chem Rev. 2003;103(12):5125–5162. doi: 10.1021/cr020644k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiemens MH, Jackson T, Zipf EC, Erdman PW, van Egmond C. Carbon dioxide and oxygen isotope anomalies in the mesosphere and stratosphere. Science. 1995;270:969–972. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zipf E, Erdman PW (1994) Studies of trace constituents in the upper stratosphere and mesosphere using cryogenic whole air sampling techniques. NASA's Upper Atmosphere Research Program (UARP) and Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling and Analysis Program (ACMAP) Research Summaries 1992–1993: Report to Congress and the Environmental Protection Agency (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC), pp 127-128.

- 21.Alexander B, Vollmer MK, Jackson T, Weiss RF, Thiemens MH. Stratospheric CO2 isotopic anomalies and SF6 and CFC tracer concentrations in the Arctic polar vortex. Geophys Res Lett. 2001;28(21):4103–4106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lammerzahl P, Rockmann T, Brenninkmeijer CAM, Krankowsky D, Mauersberger K. Oxygen isotope composition of stratospheric carbon dioxide. Geophys Res Lett. 2002;29(12):1582. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boering KA, et al. Observations of the anomalous oxygen isotopic composition of carbon dioxide in the lower stratosphere and the flux of the anomaly to the troposphere. Geophys Res Lett. 2004;31(3):L03109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawagucci S, et al. Long-term observation of mass-independent oxygen isotope anomaly in stratospheric CO2. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8:6189–6197. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yung YL, Lee AYT, Irion FW, DeMore WB, Wen J. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere: Isotopic exchange with ozone and its use as a tracer in the middle atmosphere. J Geophys Res. 1997;102(D9):10857–10866. doi: 10.1029/97jd00528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perri MJ, Van Wyngarden AL, Boering KA, Lin JJ, Lee YT. Dynamics of the O(1D)+CO2 oxygen isotope exchange reaction. J Chem Phys. 2003;119(16):8213–8216. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang MC, Blake GA, Lewis BR, Yung YL. Oxygen isotopic composition of carbon dioxide in the middle atmosphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(1):21–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang MC, Blake GA, Yung YL. Seasonal cycle of C16O16O, C16O17O, and C16O18O in the middle atmosphere: Implications for mesospheric dynamics and biogeochemical sources and sinks of CO2. J Geophys Res. 2008;113:D12305. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen J, Thiemens MH. Multi-isotope study of the O(1D) + CO2 exchange and stratospheric consequences. J Geophys Res. 1993;98(D7):12801–12808. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston JC, Rockmann T, Brenninkmeijer CAM. CO2 + O(1D) isotopic exchange: Laboratory and modeling studies. J Geophys Res. 2000;105(D12):15213–15229. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakraborty S, Bhattacharya SK. Experimental investigation of oxygen isotope exchange between CO2 and O(1D) and its relevance to the stratosphere. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(D23):4724. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaheen R, Janssen C, Rockmann T. Investigations of the photochemical isotope equilibrium between O2, CO2 and O3. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:495–509. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauersberger K, Krankowsky D, Janssen C. Oxygen isotope processes and transfer reactions. Space Sci Rev. 2003;106(1-4):265–279. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoag KJ, Still CJ, Fung IY, Boering KA. Triple oxygen isotope composition of tropospheric carbon dioxide as a tracer of terrestrial gross carbon fluxes. Geophys Res Lett. 2005;32(2):L02802. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luz B, Barkan E. Assessment of oceanic productivity with the triple-isotope composition of dissolved oxygen. Science. 2000;288(5473):2028–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juranek LW, et al. Biological production in the NE Pacific and its influence on air-sea CO2 flux: Evidence from dissolved oxygen isotopes and O2/Ar. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2012;117:23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luz B, Barkan E, Bender ML, Thiemens MH, Boering KA. Triple-isotope composition of atmospheric oxygen as a tracer of biosphere productivity. Nature. 1999;400(6744):547–550. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blunier T, Barnett B, Bender ML, Hendricks MB. Biological oxygen productivity during the last 60,000 years from triple oxygen isotope measurements. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2002;16(3):1029. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao HM, Lyons JR, Zhou CM. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for elevated CO2 levels after a Neoproterozoic glaciation. Nature. 2008;453(7194):504–506. doi: 10.1038/nature06959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gehler A, Tuetken T, Pack A. Triple oxygen isotope analysis of bioapatite as tracer for diagenetic alteration of bones and teeth. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2011;310(1-2):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flocke F, et al. An examination of chemistry and transport processes in the tropical lower stratosphere using observations of long-lived and short-lived compounds obtained during STRAT and POLARIS. J Geophys Res. 1999;104:26625–26642. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman PA, et al. An overview of the SOLVE/THESEO 2000 campaign. J Geophys Res. 2002;107(D20):8259. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Froidevaux L, et al. Early validation analyses of atmospheric profiles from EOS MLS on the Aura satellite. IEEE Trans Geosci Rem Sens. 2006;44(5):1106–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Assonov SS, Brenninkmeijer CAM. A new method to determine the 17O isotopic abundance in CO2 using oxygen isotope exchange with a solid oxide. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15(24):2426–2437. doi: 10.1002/rcm.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenblatt JB, et al. Tracer-based determination of vortex descent in the 1999/2000 Arctic winter. J Geophys Res. 2002;107(D20):8279. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michelsen HA, Manney GL, Gunson MR, Zander R. Correlations of stratospheric abundances of CH4 and N2O derived from ATMOS measurements. Geophys Res Lett. 1998;25:2777–2780. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen C, Guenther J, Krankowsky D, Mauersberger K. Temperature dependence of ozone rate coefficients and isotopologue fractionation in 16O-18O oxygen mixtures. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;367(1-2):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang MC, Blake GA, Yung YL. A semianalytic model for photo-induced isotopic fractionation in simple molecules. J Geophys Res. 2004;109(D10):D10308. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang MC, et al. Isotopic composition of stratospheric ozone. J Geophys Res. 2006;111:D02302. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chakraborty S, Bhattacharya SK. Oxygen isotopic fractionation during UV and visible light photodissociation of ozone. J Chem Phys. 2003;118(5):2164–2172. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cole AS, Boering KA. Mass-dependent and non-mass-dependent isotope effects in ozone photolysis: Resolving theory and experiments. J Chem Phys. 2006;125(18):184301. doi: 10.1063/1.2363984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rex M, et al. Subsidence, mixing, and denitrification of Arctic polar vortex air measured During POLARIS. J Geophys Res. 1999;104(D21):26611–26623. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ianni JC (2012) KINTECUS, Windows Version 3.962.

- 54.Morton J, Barnes J, Schueler B, Mauersberger K. Laboratory studies of heavy ozone. J Geophys Res. 1990;95(D1):901–907. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thiemens MH, Jackson T. New experimental evidence for the mechanism for production of isotopically heavy O3. Geophys Res Lett. 1988;15(7):639–642. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thiemens MH, Jackson T. Pressure dependency for heavy isotope enhancement in ozone formation. Geophys Res Lett. 1990;17(6):717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feilberg KL, Wiegel AA, Boering KA. Probing the unusual isotope effects in ozone formation: Bath gas and pressure dependence of the non-mass-dependent isotope enrichments in ozone. Chem Phys Lett. 2013;556:1–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.