Background: Myosins convert the energy of ATP hydrolysis into force production.

Results: Substitution of the metal-interacting serine in switch-1 with cysteine renders the motor sensitive to manganese.

Conclusion: This technology provides a reversible structural linkage between the nucleotide pocket and actin-binding region in the myosin motor domain.

Significance: Understanding the ATPase mechanism requires a description of allosteric communication in molecular motors.

Keywords: Actin, ATPases, Manganese, Molecular Motors, Myosin

Abstract

G-proteins, kinesins, and myosins are hydrolases that utilize a common protein fold and divalent metal cofactor (typically Mg2+) to coordinate purine nucleotide hydrolysis. The nucleoside triphosphorylase activities of these enzymes are activated through allosteric communication between the nucleotide-binding site and the activator/effector/polymer interface to convert the free energy of nucleotide hydrolysis into molecular switching (G-proteins) or force generation (kinesins and myosin). We have investigated the ATPase mechanisms of wild-type and the S237C mutant of non-muscle myosin II motor from Dictyostelium discoideum. The S237C substitution occurs in the conserved metal-interacting switch-1, and we show that this substitution modulates the actomyosin interaction based on the divalent metal present in solution. Surprisingly, S237C shows rapid basal steady-state Mg2+- or Mn2+-ATPase kinetics, but upon binding actin, its MgATPase is inhibited. This actin inhibition is relieved by Mn2+, providing a direct and experimentally reversible linkage of switch-1 and the actin-binding cleft through the swapping of divalent metals in the reaction. Using pyrenyl-labeled F-actin, we demonstrate that acto·S237C undergoes slow and weak MgATP binding, which limits the rate of steady-state catalysis. Mn2+ rescues this effect to near wild-type activity. 2′(3′)-O-(N-Methylanthraniloyl)-ADP release experiments show the need for switch-1 interaction with the metal cofactor for tight ADP binding. Our results are consistent with strong reciprocal coupling of nucleoside triphosphate and F-actin binding and provide additional evidence for the allosteric communication pathway between the nucleotide-binding site and the filament-binding region.

Introduction

Purine nucleotide-binding proteins constitute a large fraction of the hydrolase enzymes (EC 3.6) discovered in biological systems. G-proteins, kinesins, and myosins are hydrolases that utilize a common fold consisting of a central β-sheet surrounded by α-helices. Specifically, there are three primary structural elements in the active site that are used to bind the nucleotide and metal ion (typically divalent magnesium, Mg2+) and coordinate nucleotide hydrolysis (1). These conserved active site elements are called the phosphate-binding loop (P-loop2 or Walker A motif, consensus sequence GXXXXGK(S/T)), switch-1 (NXXSSR in kinesins and myosins, T in G-proteins), and switch-2 (Walker B motif; DXXG) (2–5). The P-loop interacts with the phosphates of the nucleotide and the Mg2+ cofactor. The switch-1 and switch-2 motifs function to sense and respond to the presence or absence of the γ-phosphate of the nucleotide, which is accomplished through direct interaction with the nucleotide as well as Mg2+ coordination. Four of the six ligands that satisfy the octahedral geometry for metal ion coordination are typically the hydroxyl oxygen from the side chain of the conserved P-loop serine/threonine, an oxygen from the β-phosphate, and two distinct water molecules (6). The remaining two ligands vary depending on the particular hydrolase and the nucleotide state (e.g. ATP-bound versus ADP-bound). Although there has been a wealth of research directed to understand the protein conformational changes needed for nucleotide catalysis, we have a poor understanding of the detailed mechanistic biochemistry that functions to lower the transition state free energy and achieve the accelerated rate of hydrolysis.

Myosins and kinesins are related cytoskeletal molecular motor proteins that convert the free energy of ATP hydrolysis into force generation along their filament track (filamentous actin for myosins and microtubules for kinesins). They contain a similar central core of structural elements that are thought to facilitate conformational changes in the motor domain during the ATP hydrolysis cycle (7–9). The movement of switch-1 and switch-2 is linked to the transmission of structural changes at the filament-binding interface to modulate the affinity of the motor for its track as well as to trigger displacement of the rod-like lever arm in myosins or the neck linker in kinesins. Despite the structural similarities between myosins and kinesins, the kinetic and thermodynamic mechanisms are quite different. For example, upon ATP binding to the actomyosin complex, myosin·ATP rapidly detaches from the filament before ATP hydrolysis (10), whereas ATP binding to the microtubule·kinesin complex does not typically dissociate the motor from the filament, rather it remains tightly bound and undergoes hydrolysis on the filament before detaching (11). Nevertheless, the rate-limiting reaction in the ATP hydrolysis cycle for both motors is stimulated in the presence of their respective filaments. The structural details for this filament-promoted stimulation of ATPase activity remain largely unspecified.

Actomyosin force generation occurs through cyclic interactions of filamentous actin (F-actin) and myosin cross-bridges that are mechanochemically linked to the myosin ATP hydrolysis cycle (12). The genetically truncated and recombinantly expressed non-muscle myosin II motor (called S1dC) from Dictyostelium discoideum has been a good model system for studying the actomyosin mechanochemical cycle (13). It has long been known that ATP binding to myosin results in closure of the nucleotide pocket (13, 14). Based on x-ray crystallographic and cryo-electron microscopy data, myosin switch-1 has been hypothesized to critically function in the transmission of structural information from the nucleotide-binding site to the actin-binding regions (15). The rigor-like (nucleotide-free) structure of myosin (16–18) and the post-rigor (ATP-bound) structure (19, 20) show significant conformational differences in the switch-1 loop and the actin-binding cleft. Conibear et al. (21) utilized pyrene excimer fluorescence to demonstrate reciprocal opening of the actin-binding cleft upon closure of the nucleotide-binding site during ATP binding. Using engineered tryptophan substitutions in the switch-1 region of D. discoideum myosin II, Kintses et al. (22) demonstrated that switch-1 existed in a dynamic equilibrium between two states (open and closed). Recent electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopic studies (23, 24) revealed the thermodynamics of nucleotide-binding cleft closure coupled to actin filament binding. Studies using molecular dynamics simulation methodologies have corroborated the reciprocal coupling of switch-1 closing in the ATP-bound state and actin-binding cleft opening to weaken filament affinity (25, 26). Using a combination of nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analogues and myosin mutations that block ATP hydrolysis, Yengo et al. (27) provide kinetic evidence for two distinct myosin·ATP states that have different actin binding affinities, consistent with this allosteric communication pathway. Collectively, these studies provide a strong argument for a mechanical link between the nucleotide pocket conformation and a structural change in the actin-binding cleft.

In a recent study (28), we described a strategy to control the enzymatic activity and force-generating ability of molecular motors from the kinesin superfamily using an engineered metal switch technology. This technology centers on the substitution of the conserved metal-interacting switch-1 serine (NXXSSR) with cysteine (NXXSCR), thus allowing us to take advantage of the different affinities of Mg2+ and Mn2+ for serine (–OH) and cysteine (–SH) amino acids. This substitution resulted in diminished catalytic activity in kinesins, because the serine interaction with Mg2+ was critical for catalysis. By substituting Mg2+ with Mn2+, which interacts more strongly with the thiol of cysteine, we observed a restoration of metal interaction with this residue, thus rescuing ATP catalysis. This technology has provided a powerful and direct probe for catalytically important interactions between the metal, nucleotide, and protein.

In this work, we engineered the homologous switch-1 substitution into D. discoideum myosin II to determine rescue of the switch-1 interaction with the metal during the myosin ATPase cycle. Utilizing enzyme kinetics and thermodynamic methodologies, we show that this substitution modulates the actomyosin interaction based on the divalent metal present in solution.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experimental Conditions

Experiments were conducted in ATPase buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, using sodium hydroxide, 5 mm magnesium chloride, 95 mm potassium chloride, 150 mm sucrose, and 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT)) at 298 K. Where relevant, magnesium chloride was substituted with manganese chloride or calcium chloride. Rabbit skeletal muscle actin was purified from acetone powder (29) and labeled with pyrenyliodoacetamide (30). Both unlabeled and labeled G-actin were purified using Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) gel filtration chromatography (31) and stored in 2 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.1 mm calcium chloride, and 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide under constant dialysis at 277 K. Pyrene-labeled F-actin was prepared as described (32). Unless otherwise noted, final concentrations of the reactants are reported.

Construction, Expression, and Purification of M761(WT) and S237C

Escherichia coli strain Mach1 (Invitrogen) was used for all cloning reactions. D. discoideum S1dC myosin II (DdMhcA) consisting of Pro-3–Arg-761 followed by a FLAG purification tag (C terminus encoding 761RGDYKDDDDK) was cloned into a modified pDXA-3C expression vector that codes for the native myosin II Met-1–Asp-2 by incorporation of a BamHI site (33). The S237C substitution was introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with primers 5′-CCACCCGTAACAACAATTCATGTCGTTTCGGTAAATTCATTG-3′ and 5′-CAATGAATTTACCGAAACGACATGAATTGTTGTTACGGGTGG-3′, and the resulting DNA mutation was confirmed by sequencing. D. discoideum AX3-ORF+ cells were transfected with each expression vector as described (34), and constitutive recombinant protein expression was performed by growing cells in 3 liters of AX medium (Formedium) at 294 K at 120 rpm to 107 cells/ml.

The M761(WT) myosin motor domain (hereafter referred to as WT) was purified as before (34–36). Specifically, cells (∼15 g) were lysed for 15 min at 277 K in 60 ml of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mm EDTA, 0.2 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm benzamidine, 10 μm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 tablet of Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), 2% (v/v) Triton X-100, 30 μg/ml RNase A, and 100 units of alkaline phosphatase. Cell lysis was followed by centrifugation at 186,000 × g for 45 min and homogenization of the cytoskeletal pellet with 100 ml of extraction buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.3, using sodium hydroxide, 100 mm sodium chloride, 30 mm potassium acetate, 10 mm magnesium acetate, 5 mm benzamidine, 10 μm PMSF, and 1 tablet of Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)). The centrifugation and homogenization procedure was repeated in 20 ml of the extraction buffer with 20 mm ATP to release the myosin motor domain from actin. The final centrifugation step (370,000 × g for 45 min) produced a myosin-containing supernatant that was loaded onto an anti-FLAG M1-agarose affinity resin (Sigma) equilibrated with wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm sodium chloride, and 1 mm EDTA). The protein was eluted from the column using elution buffer (wash buffer plus 0.1 mg/ml FLAG peptide (Sigma)); the pooled fractions were adjusted to 5 mm EDTA to chelate any trace divalent cations, and the protein was incubated at 277 K for 15 min before buffer exchange using a HiPrep desalting column (GE Healthcare) into final buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.3, with sodium hydroxide, 95 mm potassium acetate, 0.1 mm EDTA, 150 mm sucrose, and 1 mm DTT). The protein was concentrated to 4–5 mg/ml, frozen in small aliquots using liquid nitrogen, and stored at 193 K. For the M761(S237C) protein (hereafter referred to as S237C), manganese chloride at 10 mm was added to the extraction buffer plus ATP for promoting actomyosin dissociation. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford reagent (Sigma).

Actomyosin Cosedimentation Assays

The actomyosin cosedimentation experiments were performed by mixing myosin with phalloidin-stabilized F-actin for 10 min before the addition of either 10 mm MgATP or MnATP. These complexes were immediately centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min. Gel samples were prepared for the supernatant and pellet fractions for each reaction, and proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software (37).

Steady-state ATPase Measurements

The basal and actin-stimulated ATPase activities of WT and S237C were measured by the NADH coupled assay as described (38). Briefly, myosin or actomyosin was diluted to twice the final concentration in ATPase buffer minus Mg2+, Mn2+, or Ca2+ (named Mx2+). ATP was also diluted to 2× final concentration in ATPase buffer with 2× final Mx2+ concentration and 2× NADH mixture (final concentrations as follows: 0.5 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.4 mm NADH, 100 units/ml pyruvate kinase (Sigma), 20 units/ml lactate dehydrogenase (Sigma)). To initiate the reaction, equal volumes of myosin or actomyosin and Mx2+-ATP plus mixture were thoroughly mixed by pipetting, and 150 μl of each reaction was transferred to a 96-well microplate for absorbance reading at 340 nm for 30–240 min using a BioTek Epoch microplate spectrophotometer. A standard curve from 0 to 800 μm NADH was used to convert A340 to ADP product concentration.

ATPase activity of WT and S237C was monitored as a function of F-actin concentration using the NADH assay. The observed rates of ATP hydrolysis were normalized to 1 μm enzymatic sites and plotted as a function of F-actin concentration. For conditions where F-actin stimulation was observed, the data were fit to modified Michaelis-Menten Equation 1,

|

where Eo is the myosin concentration; kcat is the maximum ATPase rate at infinite F-actin; kbasal is the ATPase rate at zero F-actin, and K0.5, actin is the F-actin concentration required to provide one-half the maximal velocity.

For conditions where F-actin inhibition of myosin ATPase was observed, the data were fit to hyperbolic inhibition Equation 2,

|

where kbasal is the velocity at zero F-actin concentration; Ao is the amplitude of inhibition defined as the rate at infinite F-actin minus the basal velocity, and Ki, actin is the inhibition constant for F-actin.

Michaelis-Menten steady-state kinetics were measured by reacting myosin and actomyosin complexes with increasing ATP concentrations, and the observed rates of ATP hydrolysis were normalized to 1 μm enzymatic sites and plotted as a function of ATP concentration. Each data set was fit to hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten Equation 3,

|

Presteady-state Kinetic Experiments

Stopped-flow measurements were performed at 298 K using an SF-2004 (Dartmouth College) or SF-300X (Indiana University) stopped-flow apparatus (KinTek Corp.) equipped with a xenon arc lamp (Hamamatsu). In experiments to measure ATP-promoted actomyosin dissociation, pyrenyl-F-actin filaments (1:5 labeled/unlabeled) were equilibrated with 2-fold excess myosin for 30 min, followed by rapid mixing in the stopped-flow with Mx2+ATP. Pyrene fluorescence was monitored over time, λex, max = 365 nm, λem, max = 407 nm (400-nm long pass filter). For experiments at increasing ATP concentration, the observed exponential rate of ATP-promoted actomyosin dissociation was plotted against ATP concentration and fit to the following hyperbola based on Scheme 1,

|

where kobs is the observed rate of the exponential change of fluorescence intensity; k+2 is the rate constant for the ATP-dependent isomerization (Scheme 1), and Kd, ATP is the dissociation constant for weak ATP binding forming the collision complex AM·ATP.

SCHEME 1.

Inorganic phosphate (Pi) product release from myosin was determined using the MDCC-PBP coupled assay, as described previously (11, 39–41). Specifically, WT and S237C were equilibrated with MDCC-PBP and Pi mop, followed by rapid mixing with Mx2+-ATP plus Pi mop. The Pi mop removes the 1–2 μm contaminating Pi present in the buffers, and the concentrations of the Pi mop reagents (0.05 units/ml purine nucleotide phosphorylase, 75 μm 7-methylguanosine) were determined to effectively prevent competition with the MDCC-PBP for Pi during the reaction. The experimental design assumes that, after ATP hydrolysis, Pi product will be released from the active site of myosin and bind rapidly and tightly to the MDCC-PBP, thus triggering the fluorescent enhancement of the MDCC-PBP·Pi complex, λex, max = 425 nm, λem, max = 464 nm (450-nm long pass filter (39)). To convert the observed change in fluorescence intensity into units of Pi concentration, a Pi standard curve was used. Each nonlinear transient in Fig. 5 was fit to the following burst Equation 5,

where Ao corresponds to the concentration myosin·ADP·Pi complexes that proceed forward toward Pi release; kb is the rate of the exponential burst phase, and kss is the rate of the linear phase (μm Pi s−1) defining subsequent ATP turnovers.

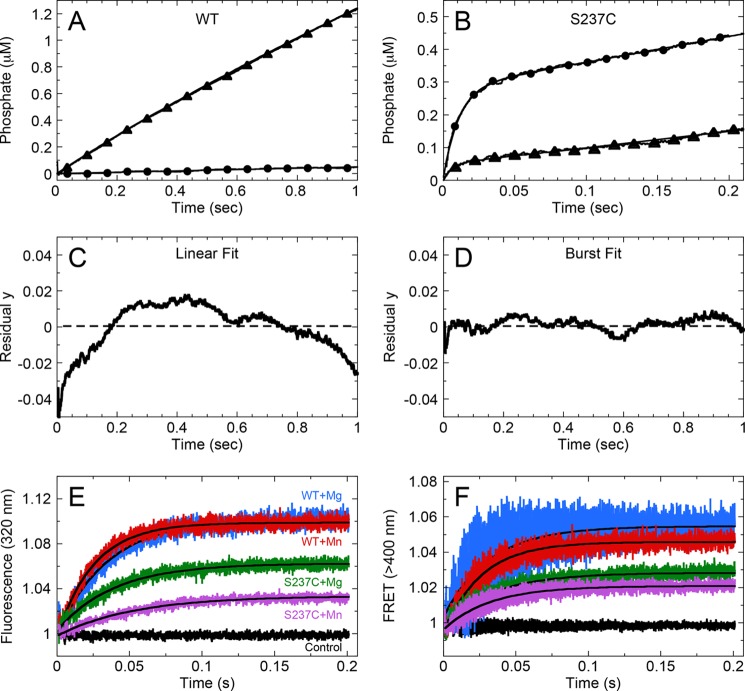

FIGURE 5.

Kinetics of inorganic phosphate release and ATP binding kinetics for WT and S237C. A, Pi release kinetics by WT (A) and S237C (B) with MgATP (circles) and MnATP (triangles) in the absence of F-actin using the MDCC-PBP-coupled assay. Final concentrations are as follows: 2 μm myosin, 10 μm MDCC-PBP, 0.05 units/ml purine nucleotide phosphorylase, 75 μm 7-methylguanosine, 500 μm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2 or MnCl2. Transient for MgATP was fit to a line, kobs = 0.05 ± 0.0002 s−1 site−1, and the transient for MnATP was fit to Equation 5, kb = 2.1 ± 0.2 s−1, Ao = 0.22 ± 0.03 μm, and kss = 1.0 ± 0.02 s−1 site−1. For S237C in MgATP, kb = 92 ± 1 s−1, Ao = 0.27 ± 0.001 μm, and kss = 0.79 ± 0.003 s−1 site−1. For S237C in MnATP, kb = 178 ± 13 s−1, Ao = 0.05 ± 0.003 μm, and kss = 0.50 ± 0.002 s−1 site−1. Linear (C) and burst (D) fitting of Pi release kinetics for WT reacted with MnATP showing residuals around the fit of the data. E, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence enhancement for WT and S237C upon binding MgATP or MnATP (as indicated; Table 2). F, WT and S237C myosin tryptophan to mant-ATP FRET in Mg2+ and Mn2+. Each transient in E and F was fit to a single exponential function.

Kinetics of ATP binding to myosin were measured using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λex = 295 nm, λem > 320-nm long pass filter) and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) from myosin tryptophans to 2′(3′)-O-(N-methyl-anthraniloyl)-ATP (mant-ATP; λex = 295 nm, λem > 400-nm long pass filter) as described previously (42–46). Transients in Fig. 5, E and F, were fit to a single exponential equation.

Kinetics of the interaction of mant-ADP with myosin was measured by equilibrating a myosin·mant-ADP (1:1) complex in excess Mx2+ followed by rapid mixing with a high concentration of the complementary Mx2+ and ATP to chase the mant-ADP from the active site as described (44). The mant fluorescence was monitored over time, λex, max = 356 nm and λem, max = 448 nm (400-nm long pass filter).

Data Analysis

DYNAFIT software (BioKin Ltd., Pullman, WA) was used to model the Pi product release kinetics for 2 μm WT at 500 μm MnATP to the mechanism proposed in Scheme 2 (47). The kinetic constants for ATP binding (K+1k+2) and ATP hydrolysis (k+3 and k−3) were fixed in value based on previous studies with WT under similar experimental conditions (Table 3) (48, 49). Because Pi binding to MDCC-PBP was both rapid and tight, Pi release from WT was modeled as an irreversible step. ADP release was also modeled as irreversible because only 0.2% of the ATP was hydrolyzed during the time course, and thus ADP product rebinding to WT would be improbable. The forward rate constants for Pi release (k+4) and ADP release (k+5) were allowed to float in the DYNAFIT regression analysis.

SCHEME 2.

TABLE 3.

Summary of Pi release kinetics for WT with MnATP from DYNAFIT

20 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 5 mm manganese chloride, 95 mm potassium acetate, 150 mm sucrose, 2 μm WT, 500 μm ATP at 298 K.

| Step | Constant | k ± S.E.a | Constant | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP binding | K+1k+2b | 0.606 μm−1 s−1 | ||

| ATP hydrolysis | k+3 c | 158.9 s−1 | k−3c | 1.1 s−1 |

| Pi release | k+4 | 0.78 ± 0.001 s−1 | ||

| ADP release | k+5 | 1.78 ± 0.02 s−1 |

a S.E. is standard error of global fitting.

b K+1k+2 represents the apparent second-order rate constant of ATP binding to WT that was reported previously (48).

RESULTS

Metal Dependence of S237C Interaction with F-actin

We began our study by engineering a serine (residue 237) to cysteine substitution in switch-1 (WT, SSR, and S237C, SCR) of the motor domain of D. discoideum S1dC myosin II. This residue has been shown to coordinate the divalent Mg2+ at the active site of myosin II when adenosine nucleotide is bound (19, 20, 36, 50–56). We hypothesized the S237C motor would display divalent cation sensitivity due to the differential affinities of Mg2+ and Mn2+ for serine (–OH) and cysteine (–SH) amino acids, similar to the switch-1 serine-to-cysteine substitution in related kinesin motors (28). Substitution of this active site serine with cysteine is expected to diminish catalytic activity if the serine interaction with Mg2+ is critical for catalysis. Substituting Mg2+ with Mn2+, which interacts more strongly with cysteine, should therefore restore the metal interaction with this residue, thus rescuing catalysis. WT and S237C proteins were expressed and purified from D. discoideum using cytoskeleton affinity and ATP release (see under see “Experimental Procedures” and Refs. 34–36) followed by anti-FLAG affinity chromatography. The WT enzyme preparation occurred as expected, but at the ATP release step, S237C was found to predominantly sediment with the F-actin cytoskeleton in the presence of Mg2+ (data not shown). However, including Mn2+ in the extraction buffer promoted actomyosin dissociation and S237C partitioned with the soluble fraction.

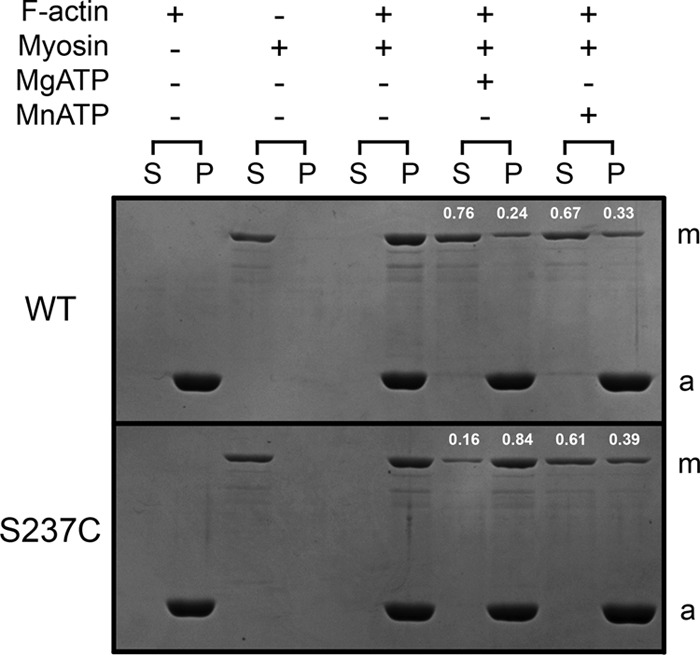

Actomyosin cosedimentation experiments were performed to assess the fraction of WT and S237C that bound to phalloidin-stabilized F-actin under different metal conditions (Fig. 1). In the absence of added nucleotide, greater than 99% of myosin bound and partitioned with F-actin, which, under these experimental conditions, was consistent with a very low Kd,actin that has been previously reported (48). For WT, a comparable fraction of myosin detached from F-actin in the presence of excess MgATP or MnATP (76 and 67%, respectively), which represented a weakening of actin binding by ∼100-fold over nucleotide-free conditions. However, S237C retained relatively tight binding to F-actin (16% detached) in the presence of MgATP, yet MnATP weakens the acto·S237C interaction (61% detached) similar to WT. Therefore, the S237C substitution appears to modulate the actomyosin interaction based on the divalent metal present in solution.

FIGURE 1.

Actomyosin cosedimentation experiments. Coomassie Blue-stained SDS gel shows sedimentation of phalloidin-stabilized F-actin with WT and S237C. The supernatant (S) and pellet (P) for each reaction were loaded consecutively with the reaction conditions indicated above each supernatant/pellet pair. Myosin is highlighted with an m and actin with an a. The fractions of myosin in the supernatant and pellet in the presence of nucleotide are labeled at the top of each lane. Final conditions are as follows: 1 μm myosin, 1.5 μm F-actin, 10 mm MgCl2 or MnCl2, 10 mm ATP.

Steady-state ATPase Kinetics Versus F-actin Concentration

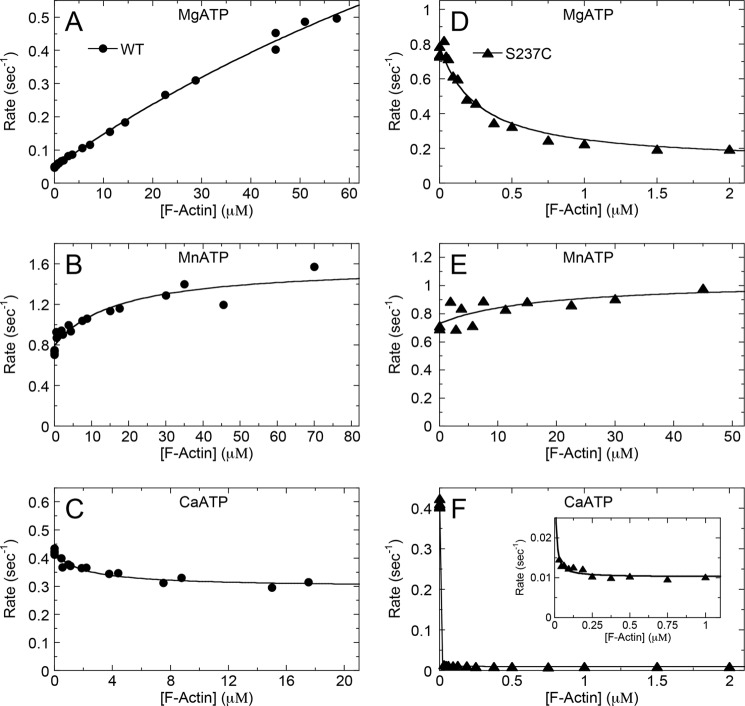

ATPase activities of WT and S237C were monitored in the presence of Mg2+, Mn2+, and Ca2+ with increasing concentrations of F-actin using the NADH-coupled assay (Fig. 2). WT displayed typical basal and actin-stimulated steady-state MgATPase kinetics (basal, kcat = 0.05 s−1 site−1; F-actin, kcat = 2.0 s−1 site−1; see Fig. 2A and Table 1) with a weak F-actin binding interaction (estimated K0.5, actin = 192 μm) as observed previously for D. discoideum S1dC myosin II (13). The MnATPase kinetics for WT showed much higher basal activity (kcat = 0.84 s−1 site−1; Table 1) that was stimulated 2-fold by F-actin (kcat = 1.6 s−1 site−1; Fig. 2B; Table 1). WT binding to F-actin in MnATP was tightened by greater than an order of magnitude (K0.5, actin = 17 μm) compared with MgATP conditions. WT demonstrated an enhanced basal CaATPase rate (kcat = 0.46 s−1 site−1; Fig. 2C and Table 1) compared with MgATP, yet F-actin inhibited its CaATPase (Ki,actin = 2.0 μm) due to the weakening of CaATP affinity for WT (see below).

FIGURE 2.

Steady-state ATPase showing F-actin concentration dependence. WT (A–C) and S237C (D–F) were reacted with increasing F-actin concentrations with excess MgATP, MnATP, or CaATP (as indicated). Final enzyme concentrations are as follows: A–C and E, 0.25 μm myosin; D and F, 25 nm myosin; 0–70 μm F-actin; 500 μm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2. A, B, and E were fit to Equation 1, and C, D, and F were fit to Equation 2 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of steady-state ATPase kinetics for WT and S237C

| Basala | F-actina | |

|---|---|---|

| WT-Mg2+ | kcat = 0.05 ± 0.001 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 2.0 ± 0.4 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 0.22 ± 0.03 μm | Km, ATP = 0.38 ± 0.04 μm b | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.22 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 5.3 μm−1 s−1 | |

| K0.5, actin = 192 ± 53 μm | ||

| WT-Mn2+ | kcat = 0.84 ± 0.05 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 1.6 ± 0.1 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 7.8 ± 1.3 μm | Km, ATP = 11.5 ± 0.8 μmb | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.11 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 0.14 μm−1 s−1 | |

| K0.5, actin = 17 ± 7 μm | ||

| WT-Ca2+ | kcat = 0.46 ± 0.02 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 0.68 ± 0.01 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 1.5 ± 0.3 μm | Km, ATP = 502 ± 26 μmb | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.31 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 0.001 μm−1 s−1 | |

| Ki, actin = 2.0 ± 0.6 μm | ||

| S237C-Mg2+ | kcat = 0.77 ± 0.03 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 0.92 ± 0.07 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 4.7 ± 0.6 μm | Km, ATP = 7800 ± 700 μmb | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.16 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 0.0001 μm−1 s−1 | |

| Ki, actin = 0.25 ± 0.05 μm | ||

| S237C-Mn2+ | kcat = 0.65 ± 0.01 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 1.0 ± 0.1 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 3.9 ± 0.2 μm | Km, ATP = 70 ± 5 μmb | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.17 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 0.014 μm−1 s−1 | |

| K0.5, actin = 17 ± 24 μm | ||

| S237C-Ca2+ | kcat = 0.48 ± 0.01 s−1 site−1 | kcat = 0.03 ± 0.01 s−1 site−1 |

| Km, ATP = 144 ± 12 μm | Km, ATP = 3500 ± 1200 μmb | |

| kcat/Km, ATP = 0.003 μm−1 s−1 | kcat/Km, ATP = 0.000009 μm−1 s−1 | |

| Ki, actin = 0.0004 ± 0.0003 μm |

a Standard error of measurement is reported for fitted constants from all experiments (n = 2–9).

b Experiments were performed with 10 μm phalloidin-stabilized F-actin.

Surprisingly, S237C displayed rapid basal MgATPase (kcat = 0.77 s−1 site−1) that was inhibited (rather than activated) in the presence of F-actin (Fig. 2D and Table 1), which yielded an apparent Ki, actin at 0.25 μm. Based on this apparent Ki, actin, we would expect 84% of the myosin to partition with 1.5 μm F-actin in excess MgATP under these conditions, which was consistent with our cosedimentation experiments (Fig. 1). In Mn2+, S237C displayed rapid ATPase (kcat = 0.65 s−1 site−1; Fig. 2E and Table 1) that was stimulated by F-actin (kcat = 1.0 s−1 site−1) and showed similar actin binding affinity (K0.5, actin = 17 μm) compared with WT. The basal CaATPase of S237C was also very rapid (kcat = 0.48 s−1 site−1), comparable with WT, but demonstrated strong actin-promoted inhibition (kcat = 0.03 s−1 site−1 and Ki, actin = 4 nm; Fig. 2F and Table 1). Together, these results support strong evidence for divalent cation regulation of the actomyosin interaction for both WT and S237C motors.

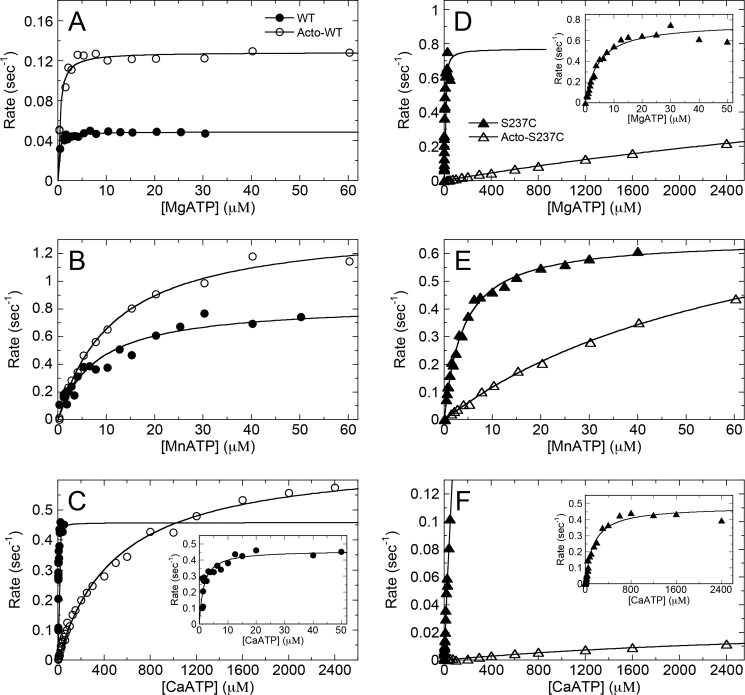

ATP Concentration Dependence of Myosin and Actomyosin ATPase

To determine the relative affinity of WT and S237C for ATP in Mg2+, Mn2+, and Ca2+ in the absence and presence of F-actin, the ATPase kinetics were monitored as a function of ATP concentration (Fig. 3). WT MgATPase kinetics in the absence and presence of F-actin (Fig. 3A) were comparable with those of a similar D. discoideum S1dC myosin II construct (57). Notably, the WT MgATPase enzymatic efficiency (kcat/Km, ATP) was significantly higher with F-actin (basal = 0.22 μm−1 s−1 versus F-actin = 5.3 μm−1 s−1; Table 1). Although F-actin stimulated WT MnATPase (Fig. 3B), the enzymatic efficiency was similar (basal = 0.11 μm−1 s−1 versus F-actin = 0.14 μm−1 s−1). In Ca2+ (Fig. 3C), F-actin promoted a dramatic weakening of ATP binding for WT (Km,ATP = 500 μm), thus leading to a marked reduction (∼300-fold lower) in enzymatic efficiency. Therefore, the presence of different excess divalent cations in solution regulates the WT·ATP and acto·WT interactions.

FIGURE 3.

Steady-state ATPase kinetics showing ATP concentration dependence. WT (A–C) and S237C (D–F) were reacted with increasing ATP concentrations and excess MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2 (as indicated) in the absence (closed symbols) or presence (open symbols) of F-actin. Final concentrations are as follows: 0.25 μm myosin, 0 or 10 μm F-actin, 0.25–2400 μm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2. Each data set was fit to Equation 3 (Table 1).

S237C MgATPase kinetics in the absence and presence of F-actin showed significantly different ATP binding affinities (Km, ATP = 4.7 μm versus 7800 μm, respectively; see Fig. 3D) leading to >1000-fold reduction in enzymatic efficiency. These data suggest that the slow rate-limiting reaction in the S237C MgATPase cycle has changed compared with WT, and the populated intermediate in the cycle is a tightly actin-bound state. In Mn2+ (Fig. 3E), the ATP binding affinity to S237C in the presence of F-actin and the F-actin binding affinity (Fig. 2E) were restored to nearly WT levels (Table 1). In Ca2+, S237C showed very weak ATP binding and slow CaATPase activity (Fig. 3F), coupled to very tight F-actin association (Fig. 2F). Together, these results support the strong reciprocal coupling of ATP and actin binding affinities, which support the model of allosteric communication between switch-1 closure via S237C interaction with the metal and weakening of the actin-binding interface.

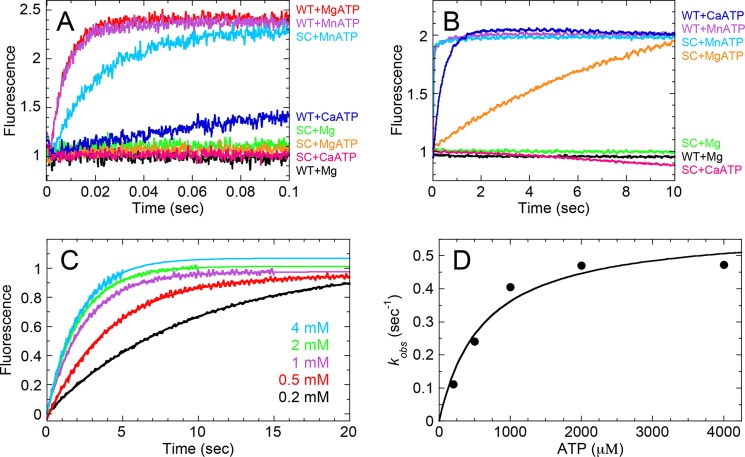

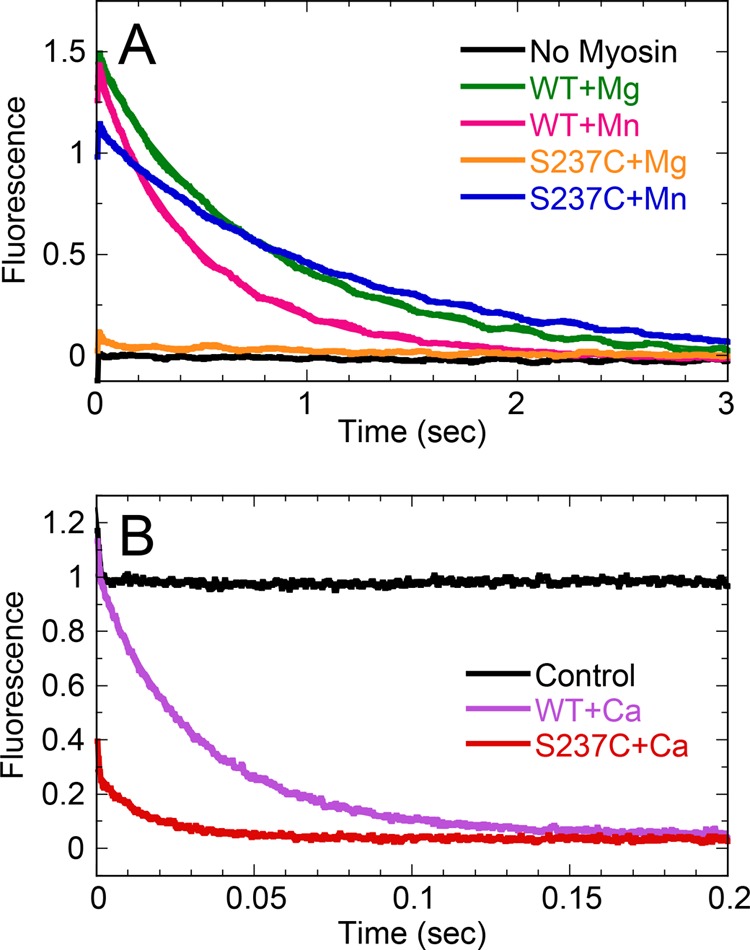

ATP-promoted Dissociation of the Actomyosin Complex

WT and S237C were complexed with pyrene-labeled F-actin (2:1) to ensure complete saturation of the F-actin lattice. This actomyosin complex was rapidly mixed with ATP and different divalent cations in a stopped-flow instrument, and pyrene fluorescence was monitored over time (Fig. 4). The experimental design assumed that myosin binding to pyrenyl-F-actin resulted in the quenching of pyrene fluorescence, but upon myosin detachment, the quenching was diminished (10, 48, 58, 59). In Fig. 4A, transients for acto·WT showed a rapid exponential increase in pyrene fluorescence upon reacting with either MgATP (kobs = 137 s−1) or MnATP (kobs = 127 s−1) but a much slower exponential increase with CaATP (kobs = 9 s−1) on the 0.1-s time scale. Acto·S237C did not show any observable change in fluorescence with either MgATP or CaATP on the same time scale, yet for MnATP, S237C dissociated rapidly (kobs = 49 s−1) albeit at a slower rate compared with WT (Fig. 4A). If the pyrene fluorescence was monitored for 10 s (Fig. 4B), S237C still did not dissociate from F-actin with CaATP but did show slow detachment with MgATP (kobs = 0.11 s−1). The observed rate of S237C detachment from pyrenyl-F-actin increased as a function of ATP concentration (Fig. 4, C and D). When the observed rate was plotted against ATP concentration and the data were fit to Equation 4, the k+2 was 0.58 s−1 and Kd,ATP was 620 μm, which was consistent with the weak Km,ATP derived from our ATP concentration dependence of the acto·S237C ATPase activity (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 4.

ATP-promoted dissociation of the actomyosin complex. The complex of pyrenyl-F-actin plus myosin was rapidly mixed with a high ATP concentration and excess of MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2. Final concentrations are as follows: 0.5 μm myosin, 0.25 μm pyrenyl-F-actin, 200 μm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2. A, control reactions for acto·WT and acto·S237C in the absence of ATP (black and green, respectively) are shown on the short time scale. Other reactions are as indicated. B, longer time scale to observe slow actomyosin dissociation reactions. C, representative transients are shown for ATP-promoted dissociation of the acto·S237C complex at increasing ATP concentrations. Final concentrations are as follows: 0.5 μm S237C, 0.25 μm pyrenyl-F-actin, 0.2–4 mm ATP (as indicated), 5 mm MgCl2. D, each transient was fit to a single exponential equation, and the observed rate was plotted as a function of ATP concentration. The data were fit to Equation 4, k+2 = 0.58 ± 0.06 s−1 and Kd, ATP = 617 ± 194 μm.

Pi Product Release Kinetics

The kinetics of Pi product release from WT and S237C were monitored using the MDCC-PBP-coupled assay in a stopped-flow instrument (39). For WT, slow linear kinetics were observed in Mg2+ (Fig. 5A), and the observed rates of Pi release were comparable with the rates measured in MgATP steady-state experiments (Figs. 2A and 3A). In Mn2+, Pi release was more rapid and displayed burst kinetics (i.e. single exponential phase followed by a linear phase; Fig. 5, A, C, and D). The observed exponential burst rate (kb) for WT was 2.1 s−1, whereas the slow steady-state rate (kss) was 1.0 s−1 site−1, which correlated well with the kcat values determined from steady-state assays (Fig. 2B; Table 1). For S237C in MgATP and MnATP (Fig. 5B), burst kinetics were observed, with more rapid Pi release during the exponential burst phase (kb = 92 and 178 s−1, respectively).

Using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 5E) and myosin tryptophan to mant-ATP FRET (Fig. 5F), the kinetics of ATP binding were measured for WT and S237C in Mg2+ and Mn2+ (Table 2). The observed rates of ATP binding using tryptophan-to-mant FRET were similar; yet we measured 1.5-fold faster kinetics for WT + Mn2+ compared with WT + Mg2+ and 1.4-fold slower kinetics for S237C + Mn2+ compared with S237C + Mg2+ using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence enhancement (Table 2). The amplitudes of the S237C transients were consistently lower compared with WT transients, although the explanation for this observation remains elusive. Overall, these results demonstrate that both WT and S237C are capable of rapidly binding Mg- or Mn-ATP, and the rate of this step does not limit the overall steady-state ATPase cycle under our experimental conditions.

TABLE 2.

ATP binding kinetics for WT and S237C in Mg2+ and Mn2+

| Reaction | Trp fluorescence (kobs) | FRET (kobs) |

|---|---|---|

| WT + Mg2+ | 28.9 ± 0.2 s−1a | 31.0 ± 1.0 s−1 |

| WT + Mn2+ | 39.5 ± 0.2 s−1 | 38.6 ± 0.4 s−1 |

| S237C + Mg2+ | 26.0 ± 0.2 s−1 | 28.5 ± 0.3 s−1 |

| S237C + Mn2+ | 18.9 ± 0.2 s−1 | 30.9 ± 0.5 s−1 |

a Standard error of the fit for 7–10 averaged transients.

The kinetics of Pi release for WT reacted with MnATP were analyzed by a four-step model (Scheme 2) using DYNAFIT (47). Given our kinetics of MnATP binding to WT are similar (based on FRET kinetics; Table 2) or are 1.5-fold faster (based on tryptophan fluorescence; Table 2), we modeled the kinetics of ATP binding as reported previously (Table 3) (48). Assuming the kinetics of ATP hydrolysis were unchanged in the presence of Mn2+, the modeled rates of Pi release and ADP release were 0.78 and 1.78 s−1, respectively (Table 3). The similar magnitude of these modeled intrinsic rate constants was consistent with the kcat value approximately half the average rate constant for these two steps (60). In other words, both Pi release and ADP release steps contribute to the slow steady-state catalytic rate constant of WT in the presence of MnATP.

ADP Product Release Kinetics

The kinetics of ADP product release from myosin were monitored using mant-ADP fluorescence as described (44). The experiment assumed that when mant-ADP was bound to the active site of myosin, its fluorescence intensity was greater than when it was free in solution. For WT, similar exponential decreases in mant fluorescence were observed in Mg2+ and Mn2+ yielding similar ADP release rates and amplitudes (Mg2+, kobs = 1.24 s−1 and Ao = 1.44; Mn2+, kobs = 1.98 s−1 and Ao = 1.37; Fig. 6A). It is worth noting that the observed rate of mant-ADP release in Mn2+ (kobs = 1.98 s−1) was similar to the DYNAFIT modeled rate constant for ADP release (k+5 = 1.78 s−1) using Pi release kinetics. S237C showed weak ADP binding in Mg2+ as demonstrated by the very small amplitude of the representative transient (Ao = 0.06; Fig. 6A). Modeling these mant-ADP binding kinetics using a two-step rapid equilibrium binding mechanism (60) supports the increase of the off-rate for the myosin·ADP collision complex as responsible for the ∼24-fold reduction of amplitude. Yet Mn2+ seemed to rescue ADP binding, although release occurred at a slower rate (kobs = 0.9 s−1) and near WT amplitude (Ao = 1.11). In Ca2+ (Fig. 6B), both WT and S237C showed rapid ADP release (kobs = 31 and 66 s−1, respectively), yet S237C had ∼25% of the amplitude compared with WT, suggesting CaADP bound more weakly to S237C compared with WT.

FIGURE 6.

mantADP release kinetics for WT and S237C. A, preformed myosin·mantADP (1:1) complex in excess MgCl2 or MnCl2 (as indicated) was rapidly mixed in a stopped-flow instrument with a high concentration of MgATP or MnATP, respectively, and mant-fluorescence emission was monitored. Final concentrations are as follows: 1 μm myosin, 1 μm mantADP, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2 or MnCl2. Transients were fit to a single exponential decay. For WT + Mg2+, kobs = 1.24 ± 0.004 s−1 and Ao = 1.44 ± 0.002; WT + Mn2+, kobs = 1.98 ± 0.007 s−1 and Ao = 1.37 ± 0.002; S237C + Mg2+, kobs = 0.90 ± 0.05 s−1 and Ao = 0.06 ± 0.001; S237C + Mn2+, kobs = 0.88 ± 0.003 s−1 and Ao = 1.11 ± 0.001. B, preformed myosin·mantADP (1:1) complex in excess CaCl2 was rapidly mixed in a stopped-flow instrument with a high concentration of CaATP. Final concentrations are as follows: 1 μm myosin, 1 μm mantADP, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm CaCl2. Transients were fit to a single exponential decay. For WT + Ca2+, kobs = 31.1 ± 0.1 s−1 and Ao = 0.95 ± 0.002; S237C + Ca2+, kobs = 66.1 ± 0.9 s−1 and Ao = 0.25 ± 0.002. Control reaction shown for the S237C·mantADP complex that was rapidly mixed with CaCl2 (no ATP).

DISCUSSION

The kinetic and thermodynamic parameters that govern the minimal basal and F-actin-stimulated ATPase mechanism of WT and S237C myosin II have been determined in the presence of different divalent cations (Mg2+, Mn2+, and Ca2+). We have provided evidence for an allosteric communication pathway between the nucleotide-binding site and the filament-binding region. When the switch-1 serine (Ser-237 in D. discoideum S1dC) was substituted with cysteine, its interaction with Mg2+ was presumed to be weakened as a result of sulfur being a poorer ligand for the hard Mg2+ ion. We observed very slow ATP binding kinetics coupled to actomyosin dissociation for S237C, suggesting that the mutant motor is still capable of closing the nucleotide pocket to trigger the conformational change at the actin-binding cleft, albeit at a markedly reduced rate. However, in the presence of Mn2+, the cysteine mutant appears to form a complete and functional active site with Mn2+, but not Mg2+ as its cofactor, leading to rapid detachment of the S237C motor from the filament. We attribute this phenomenon to the sulfur of the S237C interacting more strongly with this softer Mn2+ ion. Overall, this study demonstrates key differences between different molecular motor superfamilies (myosin versus kinesin (28)) when comparing details of nucleotide pocket movements and how these conformational changes are mapped onto their respective ATPase cycles.

Similarities and Differences of Mn2+ Versus Mg2+ and Serine Versus Cysteine

Thio-substitution and metal ion rescue experiments were developed to study the metal-catalyzed reactions of ribozymes (61) and DNA transposases (62–64). Mg2+ and Mn2+ have the same octahedral coordination geometry and a similar covalent radius (1.41 Å versus 1.39 Å, respectively). Mg2+ is a relatively hard metal ion (low polarizability and high charge density) that participates in nucleotide catalysis through coordination of oxygens from hydroxyls, carboxylates, and/or phosphates. In previous metal rescue experiments, oxygen was substituted with sulfur, which does not bind as tightly to Mg2+ but has a higher affinity for softer transition metal ions with lower charge density and somewhat greater polarizability, such as Mn2+ or Zn2+ (65). Therefore, in previous studies, the addition of Mn2+ resulted in the catalytic rescue of the sulfur-substituted macromolecule, which provided evidence for metal-binding sites that are required for the catalytic activity of different ribozymes (66–68). Mutating a serine residue to a cysteine is often thought to be a very conservative amino acid substitution in proteins due to only one atom being different (–OH in serine versus –SH in cysteine). However, the serine oxygen has an atomic radius that is 0.4 Å smaller than the sulfur in cysteine, with modestly different bond lengths and angles (69–71). These structural differences can lead to dramatic changes in ligand binding affinity, both due to steric effects as well as a change in the detailed hydrogen bonding geometry (72). However, in this study, the interaction between serine or cysteine and the divalent metal cation involves a direct bond between the metal and oxygen (from serine) or sulfur (from cysteine) with no intervening hydrogen. Therefore, although steric effects could certainly alter the structure of the myosin-active site for S237C with bound Mn2+, the effects are not expected to be as drastic as those when cysteine is acting as a hydrogen bond donor; future structural studies will provide insight into the magnitude of these effects.

Mn2+ Stimulation of WT ATPase

The mechanism of Mn2+-ATPase for skeletal muscle heavy meromyosin (HMM) was investigated in previous studies (73–75). These studies revealed that the kinetic parameters of HMM satisfy a modified Lymn-Taylor model (12) wherein the rate of Pi product release (or preceding conformational change necessary for productive lever arm movement), which limited the overall ATPase cycle, was accelerated in the presence of Mn2+. Our data on D. discoideum S1dC correlated well with these previous studies on HMM. Although our global analysis using DYNAFIT was limited to a single ATP concentration, the rate constants for Pi and ADP product release (k+4 = 0.71 s−1 and k+5 = 1.78 s−1, respectively; Scheme 2) were similar to the intrinsic rates for HMM (k+4 = 0.7 s−1 and k+5 = 1.2 s−1 (74, 75)). Our mant-ADP release results (Fig. 6) corroborate the intrinsic rate constant for ADP release with an observed rate constant of 1.98 s−1. We suggest that our steady-state acceleration in the presence of Mn2+ demonstrates a similar effect as Ca2+ activation of S1dC (13). The catalytic constant (kcat) includes two relatively slow steps in the basal ATPase cycle (in the absence of F-actin) leading to an overall kcat approximately half the magnitude of the intrinsic constants (60).

Structural Link Demonstrated for Communication between the Nucleotide Pocket and Actin-binding Cleft Using Metal Switch Technology

Despite the acceleration of the Mn2+-ATPase cycle, the overall mechanochemical cycle of WT S1dC in the presence of F-actin remained the same. We observed strong reciprocal coupling of nucleotide and F-actin binding such that upon rapid ATP binding, the myosin·MnATP complex rapidly detached from the filament (Fig. 4). For S237C in the absence of F-actin, the binding of MgATP was relatively unaffected, but in the presence of F-actin, ATP binding was weak as evidenced by steady-state ATPase (Fig. 3) and ATP-promoted actomyosin dissociation (Fig. 4) experiments. Our cosedimentation data (Fig. 1) demonstrated that S237C remains tightly bound to F-actin in MgATP, consistent with the reciprocal binding mechanism for myosin (i.e. weak ATP binding coupled to strong F-actin binding and vice versa). We propose the S237C switch-1 closes very slowly when bound to F-actin in the presence of Mg2+, and thus, the structural linkage between the nucleotide pocket and actin-binding cleft opening is perturbed. However, upon reversibly restoring the interaction between S237C switch-1 and the Mn2+ metal, the structural communication pathway is established, and the enzyme can bind MnATP tightly and thus weaken its affinity for F-actin. This represents evidence for a direct and experimentally reversible linkage (i.e. swapping of metals in the reaction) of switch-1 and actin-binding cleft through conformational switching. This finding generally agrees with previous studies of different stages of force production in myosin (76–79) and supports the previously proposed model (16, 80) that ATP binding induces closure of switch-1, resulting in release of myosin from actin.

Rapid Basal ATPase for S237C in MgATP Supports Dynamic Switch-1 in the Absence of Actin

Unexpectedly, we observed ∼17-fold enhancement of basal S237C MgATPase and similar CaATPase compared with WT (Fig. 2; Table 1). Shimada et al. (57) characterized the ATPase activity of D. discoideum S1dC mutant S237A and found ∼3-fold reduction in basal MgATPase as well as ∼10-fold reduction in actin-stimulated and CaATPase. There are a variety of methodologies that support at least two conformational states of switch-1 when different nucleotides are bound at the active site, and the equilibrium distribution of these states is modulated through actin binding (22, 23, 81, 82). Our results suggest that S237C switch-1 must be able to rapidly close in the MgATP state to establish the proper conformation necessary to lower the transition state free energy of hydrolysis. However, upon binding to actin, allosteric communication from the actin-binding interface promotes the opening of switch-1 and significantly weakens the interaction of Mg2+ by S237C such that substrate binding becomes rate-limiting in the ATPase cycle. It is thought that upon reaching the rigor state (nucleotide-free myosin bound to actin) the central β-sheet undergoes a conformational change through twisting of the sheet (15, 16, 18, 26, 56, 83). This favorable or low energy state of the central β-sheet must be reversed through favorable interactions between the residues in the active site and MgATP. Our results support the model that, in the presence of Mg2+, S237C tips the conformational equilibrium toward the open switch-1 state, thus abolishing rapid untwisting of the central β-sheet to drive actin detachment. It remains to be determined whether this slow closure of switch-1 S237C upon binding MgATP is capable of generating force during the ATPase cycle. Although the M761 fragments behave normally in all the assays presented here, it has not been found to be capable of actin movement in motility assays (48). Thus, the S237C mutation will need to be tested in future studies using a longer fragment of D. discoideum myosin II or a M761 fusion with one or two α-actinin repeats, which have been shown to display robust actin motility (45, 48).

Switch-1 Interaction with Metal Is Important for the Mechanism of Product Release in Myosin

Serine 237 has been shown to coordinate the divalent Mg2+ at the active site of D. discoideum S1dC myosin II when adenosine nucleotide is bound (19, 20, 36, 50–56). Although most myosin crystal structures in the MgADP state show switch-1 closed and coordinating the Mg2+, several kinetic and thermodynamic studies demonstrate that the switch-1 conformation is dynamic in the MgADP state with the closed conformation being thermodynamically favorable (22, 24, 82, 84, 85). However, kinesin structures in the MgADP state show switch-1 predominantly open, although conformational dynamics are observed (86–88). When comparing the analogous switch-1 serine-to-cysteine substitution in kinesin (28) and myosin, there is a dramatic difference in mant-ADP release behavior in these motors. For S233C in kinesin-5 (human Eg5/KSP), there was little difference in ADP binding affinity or release kinetics in the absence or presence of microtubules (28). However, in this study, we observe a significant difference in mant-ADP binding affinity for S237C in Mg2+ as demonstrated by the ∼24-fold reduction in amplitude of the S237C transient under these conditions (Fig. 6). Despite this reduction of amplitude, the observed rate constant was comparable with WT in Mg2+, suggesting that switch-1 dynamics are not limiting the rate constant for release, but the loss of interaction between switch-1 S237C and Mg2+ increases the off-rate for the myosin·ADP collision complex. However, in the presence of Mn2+, the switch-1 interaction is established with the metal, and the affinity for ADP was rescued to near WT level.

Metal Switch Technological Applications in Other ATPases

There are vast arrays of hydrolases that utilize a threonine or serine residue to bind a divalent magnesium cofactor in the nucleotide-binding site. As this technology has been demonstrated for kinesins (28) and now myosin, it will be interesting to speculate on the application of this technology for other P-loop-containing ATPases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harry Higgs and Earnest Heimsath for providing actin and Ming Lee for help in purifying myosin.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM097079 (to F. J. K.).

- P-loop

- phosphate-binding loop

- F-actin

- filamentous actin

- M761

- N-terminal motor domain (amino acids 1–761) of myosin II from D. discoideum

- MDCC-PBP

- 7-(diethylamino)-3-[[[(2-maleimidyl)ethyl]amino]carbonyl]coumarin-labeled phosphate-binding protein

- mant

- 2′(3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl)

- HMM

- heavy meromyosin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vale R. D. (1996) Switches, latches, and amplifiers: common themes of G proteins and molecular motors. J. Cell Biol. 135, 291–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marx A., Müller J., Mandelkow E. (2005) The structure of microtubule motor proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 71, 299–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vale R. D., Milligan R. A. (2000) The way things move: looking under the hood of molecular motor proteins. Science 288, 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sprang S. R. (1997) G protein mechanisms: insights from structural analysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 639–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kull F. J., Vale R. D., Fletterick R. J. (1998) The case for a common ancestor: kinesin and myosin motor proteins and G proteins. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 19, 877–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. John J., Rensland H., Schlichting I., Vetter I., Borasio G. D., Goody R. S., Wittinghofer A. (1993) Kinetic and structural analysis of the Mg2+-binding site of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein p21H-ras. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 923–929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kull F. J., Sablin E. P., Lau R., Fletterick R. J., Vale R. D. (1996) Crystal structure of the kinesin motor domain reveals a structural similarity to myosin. Nature 380, 550–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kull F. J., Endow S. A. (2002) Kinesin: switch I & II and the motor mechanism. J. Cell Sci. 115, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sack S., Kull F. J., Mandelkow E. (1999) Motor proteins of the kinesin family. Structures, variations, and nucleotide binding sites. Eur. J. Biochem. 262, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurzawa S. E., Geeves M. A. (1996) A novel stopped-flow method for measuring the affinity of actin for myosin head fragments using microgram quantities of protein. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 17, 669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gilbert S. P., Webb M. R., Brune M., Johnson K. A. (1995) Pathway of processive ATP hydrolysis by kinesin. Nature 373, 671–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lymn R. W., Taylor E. W. (1971) Mechanism of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis by actomyosin. Biochemistry 10, 4617–4624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bobkov A. A., Sutoh K., Reisler E. (1997) Nucleotide and actin binding properties of the isolated motor domain from Dictyostelium discoideum myosin. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 18, 563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hiratsuka T. (1994) Nucleotide-induced closure of the ATP-binding pocket in myosin subfragment-1. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27251–27257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holmes K. C., Angert I., Kull F. J., Jahn W., Schröder R. R. (2003) Electron cryo-microscopy shows how strong binding of myosin to actin releases nucleotide. Nature 425, 423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reubold T. F., Eschenburg S., Becker A., Kull F. J., Manstein D. J. (2003) A structural model for actin-induced nucleotide release in myosin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 826–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coureux P. D., Wells A. L., Ménétrey J., Yengo C. M., Morris C. A., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. (2003) A structural state of the myosin V motor without bound nucleotide. Nature 425, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holmes K. C., Schröder R. R., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. (2004) The structure of the rigor complex and its implications for the power stroke. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1819–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith C. A., Rayment I. (1996) X-ray structure of the magnesium(II)·ADP·vanadate complex of the Dictyostelium discoideum myosin motor domain to 1.9 Å resolution. Biochemistry 35, 5404–5417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fisher A. J., Smith C. A., Thoden J. B., Smith R., Sutoh K., Holden H. M., Rayment I. (1995) X-ray structures of the myosin motor domain of Dictyostelium discoideum complexed with MgADP·BeFx and MgADP·AlF4−. Biochemistry 34, 8960–8972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conibear P. B., Bagshaw C. R., Fajer P. G., Kovács M., Málnási-Csizmadia A. (2003) Myosin cleft movement and its coupling to actomyosin dissociation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 831–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kintses B., Gyimesi M., Pearson D. S., Geeves M. A., Zeng W., Bagshaw C. R., Málnási-Csizmadia A. (2007) Reversible movement of switch 1 loop of myosin determines actin interaction. EMBO J. 26, 265–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Purcell T. J., Naber N., Franks-Skiba K., Dunn A. R., Eldred C. C., Berger C. L., Málnási-Csizmadia A., Spudich J. A., Swank D. M., Pate E., Cooke R. (2011) Nucleotide pocket thermodynamics measured by EPR reveal how energy partitioning relates myosin speed to efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naber N., Málnási-Csizmadia A., Purcell T. J., Cooke R., Pate E. (2010) Combining EPR with fluorescence spectroscopy to monitor conformational changes at the myosin nucleotide pocket. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 937–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ovchinnikov V., Trout B. L., Karplus M. (2010) Mechanical coupling in myosin V: a simulation study. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 815–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zheng W. (2010) Multiscale modeling of structural dynamics underlying force generation and product release in actomyosin complex. Proteins 78, 638–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yengo C. M., De la Cruz E. M., Safer D., Ostap E. M., Sweeney H. L. (2002) Kinetic characterization of the weak binding states of myosin V. Biochemistry 41, 8508–8517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cochran J. C., Zhao Y. C., Wilcox D. E., Kull F. J. (2012) A metal switch for controlling the activity of molecular motor proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.19, 122–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spudich J. A., Watt S. (1971) The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 246, 4866–4871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pollard T. D., Cooper J. A. (1984) Quantitative analysis of the effect of Acanthamoeba profilin on actin filament nucleation and elongation. Biochemistry 23, 6631–6641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacLean-Fletcher S., Pollard T. D. (1980) Mechanism of action of cytochalasin B on actin. Cell 20, 329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heimsath E. G., Jr., Higgs H. N. (2012) The C terminus of formin FMNL3 accelerates actin polymerization and contains a WH2 domain-like sequence that binds both monomers and filament barbed ends. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3087–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Manstein D. J., Hunt D. M. (1995) Overexpression of myosin motor domains in Dictyostelium: screening of transformants and purification of the affinity tagged protein. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 16, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frye J. J., Klenchin V. A., Bagshaw C. R., Rayment I. (2010) Insights into the importance of hydrogen bonding in the γ-phosphate binding pocket of myosin: structural and functional studies of serine 236. Biochemistry 49, 4897–4907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Itakura S., Yamakawa H., Toyoshima Y. Y., Ishijima A., Kojima T., Harada Y., Yanagida T., Wakabayashi T., Sutoh K. (1993) Force-generating domain of myosin motor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196, 1504–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Allingham J. S., Smith R., Rayment I. (2005) The structural basis of blebbistatin inhibition and specificity for myosin II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 378–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De La Cruz E. M., Sweeney H. L., Ostap E. M. (2000) ADP inhibition of myosin V ATPase activity. Biophys. J. 79, 1524–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brune M., Hunter J. L., Corrie J. E., Webb M. R. (1994) Direct, real-time measurement of rapid inorganic phosphate release using a novel fluorescent probe and its application to actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. Biochemistry 33, 8262–8271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klumpp L. M., Hoenger A., Gilbert S. P. (2004) Kinesin's second step. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3444–3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cochran J. C., Gilbert S. P. (2005) ATPase mechanism of Eg5 in the absence of microtubules: insight into microtubule activation and allosteric inhibition by monastrol. Biochemistry 44, 16633–16648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bagshaw C. R., Trentham D. R. (1974) The characterization of myosin-product complexes and of product-release steps during the magnesium ion-dependent adenosine triphosphatase reaction. Biochem. J. 141, 331–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Johnson K. A., Taylor E. W. (1978) Intermediate states of subfragment 1 and actosubfragment 1 ATPase: reevaluation of the mechanism. Biochemistry 17, 3432–3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woodward S. K., Eccleston J. F., Geeves M. A. (1991) Kinetics of the interaction of 2′(3′)-O-(N-methylanthraniloyl)-ATP with myosin subfragment 1 and actomyosin subfragment 1: characterization of two acto-S1-ADP complexes. Biochemistry 30, 422–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ritchie M. D., Geeves M. A., Woodward S. K., Manstein D. J. (1993) Kinetic characterization of a cytoplasmic myosin motor domain expressed in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8619–8623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Woodward S. K., Geeves M. A., Manstein D. J. (1995) Kinetic characterization of the catalytic domain of Dictyostelium discoideum myosin. Biochemistry 34, 16056–16064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kuzmic P. (1996) Program DYNAFIT for the analysis of enzyme kinetic data: application to HIV proteinase. Anal. Biochem. 237, 260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kurzawa S. E., Manstein D. J., Geeves M. A. (1997) Dictyostelium discoideum myosin II: characterization of functional myosin motor fragments. Biochemistry 36, 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Malnasi-Csizmadia A., Kovacs M., Woolley R. J., Botchway S. W., Bagshaw C. R. (2001) The dynamics of the relay loop tryptophan residue in the Dictyostelium myosin motor domain and the origin of spectroscopic signals. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19483–19490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gulick A. M., Bauer C. B., Thoden J. B., Rayment I. (1997) X-ray structures of the MgADP, MgATPγS, and MgAMPPNP complexes of the Dictyostelium discoideum myosin motor domain. Biochemistry 36, 11619–11628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Houdusse A., Kalabokis V. N., Himmel D., Szent-Györgyi A. G., Cohen C. (1999) Atomic structure of scallop myosin subfragment S1 complexed with MgADP: a novel conformation of the myosin head. Cell 97, 459–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kliche W., Fujita-Becker S., Kollmar M., Manstein D. J., Kull F. J. (2001) Structure of a genetically engineered molecular motor. EMBO J. 20, 40–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Niemann H. H., Knetsch M. L., Scherer A., Manstein D. J., Kull F. J. (2001) Crystal structure of a dynamin GTPase domain in both nucleotide-free and GDP-bound forms. EMBO J. 20, 5813–5821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dominguez R., Freyzon Y., Trybus K. M., Cohen C. (1998) Crystal structure of a vertebrate smooth muscle myosin motor domain and its complex with the essential light chain: visualization of the pre-power stroke state. Cell 94, 559–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Himmel D. M., Gourinath S., Reshetnikova L., Shen Y., Szent-Györgyi A. G., Cohen C. (2002) Crystallographic findings on the internally uncoupled and near-rigor states of myosin: further insights into the mechanics of the motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12645–12650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang Y., Gourinath S., Kovács M., Nyitray L., Reutzel R., Himmel D. M., O'Neall-Hennessey E., Reshetnikova L., Szent-Györgyi A. G., Brown J. H., Cohen C. (2007) Rigor-like structures from muscle myosins reveal key mechanical elements in the transduction pathways of this allosteric motor. Structure 15, 553–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shimada T., Sasaki N., Ohkura R., Sutoh K. (1997) Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the switch I region in the ATPase site of Dictyostelium discoideum myosin II. Biochemistry 36, 14037–14043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kouyama T., Mihashi K. (1981) Fluorimetry study of N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerization and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur. J. Biochem. 114, 33–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Criddle A. H., Geeves M. A., Jeffries T. (1985) The use of actin labelled with N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide to study the interaction of actin with myosin subfragments and troponin/tropomyosin. Biochem. J. 232, 343–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johnson K. A. (1992) in The Enzymes (Sigman D. S., ed) pp. 1–61, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 61. Frederiksen J. K., Piccirilli J. A. (2009) Identification of catalytic metal ion ligands in ribozymes. Methods 49, 148–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sarnovsky R. J., May E. W., Craig N. L. (1996) The Tn7 transposase is a heteromeric complex in which DNA breakage and joining activities are distributed between different gene products. EMBO J. 15, 6348–6361 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Allingham J. S., Pribil P. A., Haniford D. B. (1999) All three residues of the Tn 10 transposase DDE catalytic triad function in divalent metal ion binding. J. Mol. Biol. 289, 1195–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gao K., Wong S., Bushman F. (2004) Metal binding by the D,DX35E motif of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: selective rescue of Cys substitutions by Mn2+ in vitro. J. Virol. 78, 6715–6722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jaffe E. K., Cohn M. (1979) Diastereomers of the nucleoside phosphorothioates as probes of the structure of the metal nucleotide substrates and of the nucleotide binding site of yeast hexokinase. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 10839–10845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Piccirilli J. A., Vyle J. S., Caruthers M. H., Cech T. R. (1993) Metal ion catalysis in the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction. Nature 361, 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sontheimer E. J., Sun S., Piccirilli J. A. (1997) Metal ion catalysis during splicing of premessenger RNA. Nature 388, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sontheimer E. J., Gordon P. M., Piccirilli J. A. (1999) Metal ion catalysis during group II intron self-splicing: parallels with the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 13, 1729–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Frey M. N., Lehmann M. S., Koetzle T. F., Hamilton W. C. (1973) Precision neutron diffraction structure determination of protein and nucleic acid components. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 29, 876–884 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kistenmacher T. J., Rand G. A., Marsh R. E. (1974) Refinements of the crystal structures of dl-serine and anhydrase l-serine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 30, 2573–2578 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kerr K. A., Ashmore J. P. (1975) A neutron diffraction study of l-cysteine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 31, 2022–2026 [Google Scholar]

- 72. He J. J., Quiocho F. A. (1991) A nonconservative serine to cysteine mutation in the sulfate-binding protein, a transport receptor. Science 251, 1479–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Furukawa K. I., Ikebe M., Inoue A., Tonomura Y. (1980) The amount of nucleotide binding and the P1-burst size of myosin adenosinetriphosphatase: evidence for the nonidentical two-headed structure of myosin. J. Biochem. 88, 1629–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ikebe M., Inoue A., Tonomura Y. (1980) Reaction mechanism of Mn2+-ATPase of acto-H-meromyosin in 0.1 m KCl at 5°C: evidence for the Lymn-Taylor mechanism. J. Biochem. 88, 1653–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Inoue A., Ikebe M., Tonomura Y. (1980) Mechanism of the Mg2+- and Mn2+-ATPase reactions of acto-H-meromyosin and acto-subfragment-1 in the absence of KCl at room temperature: direct decomposition of the complex of myosin-P-ADP with F-actin. J. Biochem. 88, 1663–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Shih W. M., Gryczynski Z., Lakowicz J. R., Spudich J. A. (2000) A FRET-based sensor reveals large ATP hydrolysis-induced conformational changes and three distinct states of the molecular motor myosin. Cell 102, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Whittaker M., Wilson-Kubalek E. M., Smith J. E., Faust L., Milligan R. A., Sweeney H. L. (1995) A 35-A movement of smooth muscle myosin on ADP release. Nature 378, 748–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gollub J., Cremo C. R., Cooke R. (1999) Phosphorylation regulates the ADP-induced rotation of the light chain domain of smooth muscle myosin. Biochemistry 38, 10107–10118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Veigel C., Coluccio L. M., Jontes J. D., Sparrow J. C., Milligan R. A., Molloy J. E. (1999) The motor protein myosin-I produces its working stroke in two steps. Nature 398, 530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kull F. J., Endow S. A. (2004) A new structural state of myosin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hannemann D. E., Cao W., Olivares A. O., Robblee J. P., De La Cruz E. M. (2005) Magnesium, ADP, and actin binding linkage of myosin V: evidence for multiple myosin V-ADP and actomyosin V-ADP states. Biochemistry 44, 8826–8840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rosenfeld S. S., Xing J., Whitaker M., Cheung H. C., Brown F., Wells A., Milligan R. A., Sweeney H. L. (2000) Kinetic and spectroscopic evidence for three actomyosin:ADP states in smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25418–25426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Coureux P. D., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. (2004) Three myosin V structures delineate essential features of chemo-mechanical transduction. EMBO J. 23, 4527–4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Conibear P. B., Málnási-Csizmadia A., Bagshaw C. R. (2004) The effect of F-actin on the relay helix position of myosin II, as revealed by tryptophan fluorescence, and its implications for mechanochemical coupling. Biochemistry 43, 15404–15417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Málnási-Csizmadia A., Dickens J. L., Zeng W., Bagshaw C. R. (2005) Switch movements and the myosin crossbridge stroke. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 26, 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Minehardt T. J., Cooke R., Pate E., Kollman P. A. (2001) Molecular dynamics study of the energetic, mechanistic, and structural implications of a closed phosphate tube in ncd. Biophys. J. 80, 1151–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Naber N., Minehardt T. J., Rice S., Chen X., Grammer J., Matuska M., Vale R. D., Kollman P. A., Car R., Yount R. G., Cooke R., Pate E. (2003) Closing of the nucleotide pocket of kinesin-family motors upon binding to microtubules. Science 300, 798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Naber N., Rice S., Matuska M., Vale R. D., Cooke R., Pate E. (2003) EPR spectroscopy shows a microtubule-dependent conformational change in the kinesin switch 1 domain. Biophys. J. 84, 3190–3196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Málnási-Csizmadia A., Pearson D. S., Kovács M., Woolley R. J., Geeves M. A., Bagshaw C. R. (2001) Kinetic resolution of a conformational transition and the ATP hydrolysis step using relaxation methods with a Dictyostelium myosin II mutant containing a single tryptophan residue. Biochemistry 40, 12727–12737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]